3 Thematic priorities in Norway’s international human rights policy

3.1 Three priority areas

The Government takes an integrated approach in its efforts to promote compliance with human rights commitments and obligations, and will focus its work on the following three main areas:

Individual freedom and public participation

The rule of law and legal protection

Equality and equal opportunities

Textbox 3.1 Digital diplomacy

The Foreign Service will make greater use of strategic communication to publicise Norway’s views and priorities in the field of human rights. Digital communication channels, including social media and the missions’ websites, will be used to increase awareness of human rights issues and promote realisation of these rights, for example by reporting on discussions, decisions and universal periodic reviews in the UN. This is also an effective way of reaching out to human rights defenders, civil society and groups that experience oppression or discrimination, so that they in turn can influence the country’s authorities to comply with their human rights obligations.

The Foreign Service’s communications in this field will be intensified in the three priority areas: individual freedom and public participation; the rule of law and legal protection; and equality and equal opportunities.

The first area – individual freedom and public participation – concerns fundamental rights in an open and democratic society. Work in the second priority area – the rule of law and legal protection – will place emphasis on principles of the rule of law and related mechanisms for achieving well-functioning and stable states. Work in the third area – equality and equal opportunities – will focus on gender equality and vulnerable groups in society, taking as its starting point the principle that all citizens have the same rights. These three priority areas reflect the links between democracy, the rule of law and human rights, which lay the basis for peaceful societies that enjoy sustainable development and genuine opportunities for all.

The aim of Norway’s efforts in this field is to enable states to ensure that every individual’s human rights are safeguarded. This means that national legislation must be brought in line with international law, effective policies must be developed and systems for providing necessary services must be established. Norway’s efforts are not to compensate for any failure on the part of the authorities in other countries to shoulder their responsibilities, but to promote positive developments that are underpinned by national responsibility.

Textbox 3.2 An independent cultural sector

An independent cultural sector is a clear sign of a vibrant civil society. Free artistic expression is a right in itself. The arts can also put human rights on the agenda, encourage public participation, debate and criticism, and foster greater respect for human rights. A strong cultural sector can be an effective agent of change, and can contribute to state-building and democratic processes.

However, an independent cultural sector is not possible unless cultural rights are respected. There are significant differences both within countries and between countries in terms of respect for cultural rights, and thus the conditions for cultural workers. The protection of copyright and other intellectual property rights is crucial for artists to be able to make a living from their work, but many countries do not have adequate legislation in this area. As a result, artists are unable to support themselves, and hence the business potential that the creative industries can offer is not made full use of.

3.2 Individual freedom and public participation

Dictators are not in the business of allowing elections that could remove them from their thrones.

Gene Sharp

As individual freedom and public participation are key components of an open, democratic society, efforts to protect and expand democratic space will be given priority. Freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and association, freedom of religion or belief, the right to education, and access to independent media and information are all crucial to genuine participation in, and the opportunity to influence, political decision-making processes. Having the opportunity to influence decisions that affect you is a fundamental condition for a living democracy, and is essential for safeguarding shared values in a sustainable way. Technological developments contribute to better information flow and more openness, but they also mean increased potential for surveillance, control and sanctions.

Textbox 3.3 The importance of a strong civil society

A strong and pluralistic civil society is a driving force in efforts to promote democratic development, the rule of law and human rights. Civil society is by nature diverse, being made up of groups with different – and sometimes conflicting – interests, not least in countries where there are major disparities or conflicts. The term ‘civil society’ is used to refer to non-governmental and non-commercial actors, including special interest organisations, support groups, religious and belief groups, social movements, cultural actors and environmental organisations.

Cooperation with civil society is often crucial for improving compliance with human rights obligations. The knowledge, networks and capabilities of civil society organisations are often vital for dealing with acute situations as well as for long-term human rights efforts. Moreover, civil society, both in Norway and in other countries, plays an important part in evaluating and challenging the work carried out by the Norwegian authorities. Civil society organisations can act as a catalyst and a watchdog for the authorities in their country, and are a key source of information for Norwegian missions abroad. In many countries, civil society organisations are involved in running hospitals and schools and providing other social services. By doing so, they are making important contributions to the implementation of the country’s plans for the health, education and social welfare sectors, and thus helping to build up the country’s own capacity to fulfil its human rights obligations. Civil society actors also perform valuable work in humanitarian crises.

The Government will therefore give priority to strengthening its cooperation with civil society in its partner countries, and in its general human rights work. In particular, the Government will support civil society in countries where there are considerable human rights challenges and where democracy is under pressure. In order to ensure that our efforts contribute to a real improvement in human rights, particularly for vulnerable groups, it is essential to understand the connections between the various civil society actors and, for example, political parties and extremist groups. The part each organisation can play must be considered in light of the political and socioeconomic context, and the extent to which it can advance human rights in the local setting. Norway may provide support directly to local civil society organisations or via Norwegian partners or international organisations and networks. Our support is intended to reinforce the country’s own efforts, and should not be seen as a mere replacement.

The Government also attaches great importance to cooperating with civil society in international forums, and believes that the voice of civil society must be heard in these settings. Norway will actively seek to ensure that civil society has the opportunity to participate in a meaningful way in multilateral human rights efforts. It is important to prevent threats, attacks and reprisals against human rights defenders and other actors that cooperate with multilateral organisations.

Obstructing and silencing civil society and independent media is a threat to democracy. In many countries, human rights defenders, trade union representatives, editors, journalists and bloggers are harassed or subjected to arbitrary imprisonment, summary trial, threats or torture. They may even disappear or be killed. There have also been instances of authorities obstructing artistic freedom and shutting down forums for presenting arts and culture, and failing to protect artists and cultural workers from pressure and abuse from other groups in society. A number of countries have passed restrictive laws making it difficult to register NGOs and limiting their scope of action, often under the pretext of anti-terror legislation or other security legislation. In some countries, civil society organisations are subjected to restraints and unwarranted reporting requirements, as well as to conditions and restrictions for foreign financial support. Although there has been an increase in the number of civil society organisations globally in recent decades, the number of independent organisations has declined in many countries as a result of requirements and restrictions of this type.

Figure 3.1 Tomaso Marcolla, Italy

3.2.1 Freedom of expression

I do not agree with what you have to say, but I’ll defend to the death your right to say it.

Evelyn Beatrice Hall in ‘The Friends of Voltaire’

Freedom of expression is enshrined in global and regional human rights conventions, and is protected in the constitution and other legislation of most countries. Freedom of expression is the very foundation of democracy. The right of the people to seek and receive information and to express their opinions freely is a prerequisite for participating in society and political life. Freedom of expression is not limited to what is said or published in traditional mass media such as newspapers, radio and television. It also applies to expressions and views that are shared on the internet, including on social media. Nor does freedom of expression apply only to information and ideas that are popular or uncontroversial – but also to those that may be perceived as controversial, shocking or offensive. Those who express criticism of power may have a particular need for protection. A free and open internet is vital for the freedom of expression.

Textbox 3.4 Freedom of expression and freedom of the press under pressure

Freedom of expression and freedom of the press are under pressure in a number of countries. Killings of journalists, denying journalists access to conflict zones, and censorship and blocking of social media are just some examples of measures used by states to restrict criticism and stifle dissent. Sustained efforts must be made to stop attacks on and killings of journalists, and when such incidents occur, they must be investigated and the perpetrators brought to justice. For every journalist that is killed, many other people are pressured to silence.

According to Freedom House, the share of the world’s population that live in a country with free media is declining, and was just 14 % in 2013.1 During the past decade there has also been an increase in violence against journalists – not least women journalists – because of their work. In many countries, journalists are harassed, attacked, arrested or killed. According to the International Federation of Journalists, 123 journalists and media workers were killed in 2013. Photographers and photojournalists are often particularly at risk. The UN has adopted several resolutions and a plan of action on the safety of journalists and the issue of impunity, which are supported by Norway. Norway also supports UNESCO and media organisations that are working to improve the safety of journalists.

1 Freedom House, Freedom of the Press 2014.

Freedom of expression is restricted and obstructed by many regimes, in part through the misuse of national legislation on blasphemy and defamation. The obstruction of freedom of expression is a reliable indicator that a regime is becoming increasingly undemocratic. Only in exceptional cases can restrictions to the freedom of expression be justified. Any restriction must have a legal basis in national legislation, serve a legitimate aim, and be necessary in a democratic society.

Challenges arise when manifestations of freedom of expression violate the rights of other people, including hate speech that incites violence. Although states are obliged to implement measures against expressions that encourage hatred and intolerance of individuals or groups, finding the right balance can be difficult. The Government’s message is twofold: hate speech must be addressed, while freedom of expression must be respected. The Government places a strong emphasis on knowledge, openness, freedom of information and dialogue in its efforts.

The Government considers freedom of expression crucial to the realisation of other human rights, and will give higher priority to promoting freedom of expression in its foreign and development policy.

Priorities:

engage actively in promoting the right to seek and receive information and to freely express opinions in multilateral forums and in bilateral cooperation;

contribute to improved protection of journalists and other media workers, bloggers, writers and others who practise free artistic expression;

develop a strategy for promoting freedom of expression and independent media in foreign and development policy.

3.2.2 Freedom of the press and independent media

A free press is the unsleeping guardian of every other right that free men prize.

Sir Winston Churchill

Free and independent media underpin any vibrant democracy. They disseminate knowledge, views and ideas that are necessary for the development of society and for individuals’ ability to exercise their rights. A strong, diversified and independent media sector can be a critical corrective to the abuse of power, corruption and lack of transparency. If the media are to carry out their role as a fourth power in society, the necessary framework must be in place, including legislation that protects the confidentiality of sources and bans censorship. Independence of the media, freedom of the press, freedom of expression and the right of access to information are vital if the media are to be able to perform their intended function in a democratic society governed by rule of law.

However, in many countries the media are threatened, their offices are ransacked, and their activities are closed down. Media licensing rules and tax legislation are misused to obstruct the work of the media. In countries where the authorities own or control the media, the opposition may well not be given a voice when elections are held, which can be decisive for the election result. New communication channels and platforms are also increasingly being regulated, controlled and sanctioned by the authorities. The concentration of media power in the hands of a few private owners can also impede the media’s ability to act as a watchdog in relation to the exercise of power in both the public and the private sector. In countries where journalists and editors are subjected to pressure and threats, self-censorship increases and democracy suffers.

Norway plays a leading role in international efforts to promote free and independent media, particularly in conflict areas and countries where democracy is under pressure. As part of this work, the Ministry will support the development of institutions and codes of press ethics inspired by the Norwegian Press Complaints Commission, the Editors’ Code of Practice and the Code of Ethics of the Norwegian press.

Figure 3.2 Egil Nyhus, Norway

Priorities:

support the development of legislation and institutions that safeguard the independence of the media, combat censorship and promote public access to information;

support training for journalists in the fields of human rights, ethical journalism, quality journalism and safety;

combat impunity for attacks on and killings of journalists and media workers.

3.2.3 Freedom of assembly and association

Freedom of assembly and association make it possible for people to express their political opinions, exercise their religion, form and join political parties and trade unions, engage in the arts and choose leaders to represent their interests. These freedoms are essential to strong and stable democracies and to the realisation of other human rights. The importance and the vulnerability of freedom of assembly and association become particularly evident when countries are preparing for and conducting elections and referendums.

Many countries have adopted legislation that restricts freedom of assembly and association, the activities of human rights defenders, and the opportunities for civil society to participate in decision-making processes on all levels. This include bans on peaceful demonstrations and rules that make it difficult to register NGOs and labour organisations, or that impose restrictions on foreign financial support.

Textbox 3.5 A free and open internet

In a short space of time, the digitisation of society has brought about profound changes in the ways in which people interact and communicate, and has contributed to the evolution of new democratic channels and to global economic development. Regulation of the internet has largely come about through private agreements within the framework of domestic legislation and jurisdiction. A number of countries have advocated increased state control over cyberspace in general and the internet in particular, with reference to the principles of national sovereignty and non-interference. For the most part, this reflects a desire to regulate and control the dissemination of information – which may well be critical of the authorities – within their own borders. The Norwegian authorities have long held that human rights apply online just as much as offline, and the Government places great emphasis on the importance of an unfragmented, free and open internet. Norway is opposed to any development that gives states greater control over the internet, and has therefore not supported processes that could lead to the development of new international regulations for digital space. The preservation and development of digital space as a catalyst for innovation and for social and economic development is a Government objective. In order to achieve this objective, close cooperation is needed both among states and between the private and public sector, nationally and internationally. The Government will work for a free and open internet that respects privacy, freedom of expression and other human rights.

Norway places great emphasis on promoting freedom of assembly and association internationally, and draws on the experience gained through the large number of clubs and organisations in Norway and our strong tradition of cooperation. One example is the cooperation between the authorities and the social partners in promoting employers’ and employees’ organisations and social dialogue in other countries.

Priorities:

work to ensure that national authorities promote and respect freedom of assembly and association, both in legislation and in practice;

promote respect for freedom of assembly and association through the UN and other international organisations, civil society and various organisations at national level that we cooperate with.

3.2.4 Protection of human rights defenders

When the rights of human rights defenders are violated, all our rights are put in jeopardy and all of us are made less safe.

Kofi Annan

The work of human rights defenders is invaluable for the realisation of human rights and crucial for the development of democracy and the rule of law. Human rights defenders promote civil and political rights as well as economic, social and cultural rights. They are individuals or groups that act to improve the protection and implementation of human rights without the use of violence or force. They defend the rights of other people, and are often advocates for vulnerable and marginalised groups who are not able to defend themselves.

Textbox 3.6 Support for democratic development

Respect for human rights is a cornerstone of democracy, just as true democracy is a prerequisite for the realisation of human rights. Norway’s continual, long-term efforts to strengthen and advance human rights, for instance through the normative work carried out in the UN and the Council of Europe, make a substantial contribution to strengthening democracy. The Norwegian authorities are broadly engaged in the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and the Council of Europe, the two most important intergovernmental organisations for monitoring and promoting the development of democracy in Europe and Eurasia.

The Government will emphasise support for democratic governance at country level, and is a major contributor to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). One of the main objectives of UNDP is to assist countries in developing systems that promote democratic governance, in part by helping countries organise elections. Through its membership on the Executive Board, Norway is actively engaged in strengthening the organisation’s follow up of human rights compliance. The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) is another key partner for democratic development. IDEA supports, inter alia, electoral reform, constitutional reforms, and increased political participation. IDEA is an intergovernmental organisation, with 29 member states from all regions of the world.

Another important partner in this context is the Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM). NORDEM recruits, trains and deploys experts on the rule of law, human rights, democracy building, good governance, and election assistance and observation to the UN, the EU, the OSCE and IDEA. Other standby rosters that are drawn on for international democracy efforts include the Norwegian Crisis Response Pool, which deploys legal experts to assist with crisis management and justice sector reform, and the Norwegian Refugee Council emergency roster (NORCAP), which deploys experts to the UN, regional organisations and national authorities to alleviate humanitarian crises. The Government will seek to ensure that these schemes function as efficiently as possible.

The authorities in many countries view the work of human rights defenders as a threat to established power structures. On several occasions, the UN has expressed grave concern about the increasing extent to which human rights defenders are threatened, stigmatised, intimidated, subject to reprisals and violence, or even killed, and about the failure to prosecute those responsible. The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation for human rights defenders has particularly drawn attention to threats against women human rights defenders and those who address human rights questions related to land rights and the exploitation of natural resources.

Textbox 3.7 UN resolution on women human rights defenders

Norway is the main sponsor of the UN resolutions on human rights defenders, and presents international initiatives to reinforce their protection. This is challenging terrain, both in the UN Human Rights Council and in the UN General Assembly, where there are divergent views on the role of human rights defenders in society.

In the autumn of 2013, Norway – in close consultation with civil society organisations – initiated a new resolution in the UN General Assembly emphasising the role of women human rights defenders.1 The resolution reflects the content of the guide for our Foreign Service, Norway’s efforts to support human rights defenders, which calls upon states to:

publically acknowledge the role and work of human rights defenders;

ensure that national legislation is in line with international obligations and does not restrict human rights defenders in their work;

develop mechanisms for consultation with human rights defenders in order to identify their need for protection and to outline effective protection measures;

involve civil society and human rights defenders in decision-making processes and the development of new legislation;

establish a focal point for human rights defenders in the central administration, and consider the possibility of developing an ‘early warning’ system;

ensure that relevant human rights training is given to the appropriate officials, including the police, the prison services and the courts;

support the role of national human rights institutions in protecting human rights defenders, and strengthen their capacity;

ensure that those responsible for attacks on human rights defenders – including non-governmental actors – are prosecuted, and call on the authorities to condemn such attacks;

ensure that due consideration is given to women human rights defenders and the particular challenges they face.

The General Assembly resolution has given an international voice to these important aims. The resolution is a step in the right direction. However, there is a vast gap between what the member states have agreed to and the reality experienced by human rights defenders in many parts of the world. The Norwegian authorities will continue to seek to translate this UN resolution into practice, through our foreign missions and partners at country level, and by maintaining our active international engagement.

1 UN General Assembly Resolution 68/181 of 18 December 2013.

Protection of human rights defenders has long been a key priority for Norway. Our overall objective is for human rights defenders to be able to carry out their work of promoting and defending human rights in all parts of the world without restrictions or threats to themselves or their families. The Norwegian authorities support human rights defenders and their work through direct contact, economic support, and dialogue with the relevant national authorities, as well as through the work of organisations such as the UN, the Council of Europe and the OSCE. Norway aims to play a leading role and to cooperate with partners in various regions to combat the increased pressure on human rights defenders and to support their work.

Norway’s Foreign Service guide to this work will be revised in light of the increased pressure on human rights defenders throughout the world.

Priorities:

play a leading role in UN negotiations on protection of human rights defenders, and seek to intensify efforts to implement the resolutions adopted by the UN General Assembly and the Human Rights Council;

increase support for regional initiatives and other schemes for protecting human rights defenders, not least women human rights defenders;

engage in close dialogue with organisations working to protect human rights defenders on how best to deal with the increased pressure they are experiencing.

3.2.5 Freedom of religion or belief

Freedom of religion or belief means that all people have the freedom to practise their religion or belief, either alone or in community with others, in public or private. It also covers the freedom to convert to another religion, to question another’s religion or belief, or to adopt atheist views. Freedom of religion or belief is closely linked to freedom of expression, the right to privacy and freedom of association and assembly.

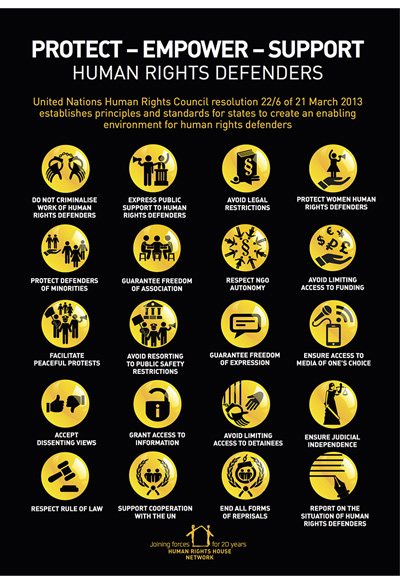

Figure 3.3 United Nations Human Rights Council resolution 22/6, sponsored by Norway and adopted by the Council in March 2013.

Source Human Rights House Foundation

Violence, intolerance and discrimination based on religious affiliation or faith is a problem, even in established democracies. Religious minorities are most often affected, and may find their freedom of religion or belief restricted in relation to the religion of the majority of the population. This can also apply to minority groups within the majority religions. In some countries, however, the majority of the population is subjected to discrimination by a ruling minority. Sometimes, freedom of religion or belief is misused to limit the rights of individuals or to deprive them of their rights, as in the case of practices that discriminate against women, or when states use freedom of religion or belief as a pretext to justify measures that are illegal. The pressure on freedom of religion or belief is greatest in times of major political and economic upheaval, when differences of religion or belief can be used by those seeking power to split the population and to consolidate their power base. Developments in the Middle East show that extreme situations can arise, involving the persecution and even mass killing of religious minorities.

Textbox 3.8 The Ministry’s guidelines on human rights work

In the Ministry’s efforts to achieve an integrated approach to human rights work, several sets of guidelines have been developed. The objective of these guidelines is to strengthen the knowledge base in the Foreign Service on key human rights issues, and to provide practical and technical advice on how the Foreign Service can maintain, intensify and systematise its efforts to promote human rights at country level. These guidelines are also designed to strengthen the work of the Foreign Service in multilateral forums and in consultations on human rights at the political level.

Guidelines have been developed on the following topics: sexual and reproductive health and rights, the rights of religious minorities, the rights of indigenous peoples, the rights of sexual minorities, the rights of persons with disabilities, work to protect human rights defenders, and efforts to abolish the death penalty. Further development of the Foreign Service’s work to promote and protect human rights will build on these guidelines.

The right to freedom of religion or belief should protect individuals, not ideologies or religions. Banning religious criticism may lead to censorship on religious issues, to the detriment of religious minorities, human rights defenders and journalists. The Norwegian authorities therefore take a stand against groups of countries and organisations that seek to limit freedom of expression with a view to preventing criticism of religions or religious figures.

In order to raise the issue of the situation for religious minorities in other countries with credibility, the Norwegian authorities must also be willing to examine the situation of religious minorities in Europe, both today and in the past. Norway therefore participates actively in international efforts to promote Holocaust remembrance, for example through membership of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, an intergovernmental organisation whose mandate includes education, research and the preservation of war monuments. The Norwegian authorities also work to promote freedom of religion or belief at the multilateral level and bilaterally, with particular emphasis on the situation of religious minorities. Long-term awareness-raising activities and the involvement of religious and faith-based organisations are necessary in order to improve the situation of religious minorities. Norway cooperates closely with civil society organisations and like-minded countries in this work.

Priorities:

seek to ensure that national authorities promote and respect freedom of religion or belief, both in legislation and in practice, and especially work to improve the situation of religious minorities;

work to ensure that religious and belief groups respect human rights, both within their own groups and in relation to society as a whole;

seek to ensure that respect for religion does not limit freedom of expression or other human rights.

3.2.6 The right to education

When the whole world is silent, even one voice becomes powerful.

Malala Yousafzai

Education is vital to an individual’s personal development, and is an important factor for realising and strengthening other human rights. Education promotes equality and equal opportunities, particularly for vulnerable groups, and facilitates empowerment and participation. When teenage girls receive an education, there is a decline in child marriage and teenage pregnancies, and a reduction in maternal and infant mortality. Education enhances girls’ social status, increases their awareness of their rights, empowers them to make their own choices and, not least, equips them to support themselves (and their families when the time comes), as well as improving their reproductive health.

Although all children have the right to education, both access to and quality of education are very unevenly distributed. As many as 57 million primary school-aged children and 70 million young people are not in school. Approximately half of all out-of-school children live in conflict-affected countries. Girls, children with disabilities, and children living in extreme poverty and in rural areas are overrepresented among those not attending school.1 The Government has therefore made education a priority area for its development policy, and presented a white paper on education for development in June 2014.2 The three main objectives for Norway’s global education effort are to help ensure that all children have the same opportunities to start and complete school, that all children and young people learn basic skills and are equipped to tackle adult life, and that as many as possible develop skills that enable them to find gainful employment.

There is a growing tendency for schools in countries experiencing conflict to be directly affected. In some situations, military groups take over school premises, while in other situations schools are directly attacked for ideological reasons, as we have seen with girls’ schools in Pakistan. Schools are often used as an arena for spreading hatred and reinforcing existing tensions. It is vital that schools seek to provide neutral ground before, during and after a conflict. An important aspect of the Government’s focus on safeguarding children’s right to education is its efforts to protect schools in countries affected by war and conflict, and it has taken on the responsibility of leading the process to finalise and promote the Safe Schools Initiative put forward by the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack.

In order to strengthen the capacity of individuals to claim their rights and to demand that these rights be respected, the Government will also focus on the promotion of human rights education. Knowledge about human rights promotes increased respect for our fellow human beings and helps to combat prejudice and stereotypes. This is also essential if human rights are to be respected and observed in practice. The Norwegian authorities will seek to make learning about human rights a compulsory part of education for all children, in line with the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The Norwegian authorities will also seek to increase awareness of human rights among key occupational groups, such as teachers, health and social service personnel, politicians, judges, lawyers, police officers, military personnel, business leaders, journalists and the media sector in general.

Norwegian students and academics have longstanding traditions of international cooperation with students and academics in developing countries. Universities are often at the centre of demands for democratic change and respect for human rights, and those who play an active role in such processes of change, may be subjected to different types of sanctions, such as not being allowed to complete their studies. The Ministry supports a scheme that makes it possible for persecuted students to continue their studies in Norway.

Priorities:

take a leading role in global efforts to ensure relevant education of good quality for all, with a particular focus on girls, children with disabilities, the poorest children, and children affected by crisis and conflict;

be at the forefront of efforts to ensure that international humanitarian law is respected and that the militarisation of and attacks on schools and universities stop, including by playing a leading role in promoting the Safe Schools Initiative internationally;

work to disseminate knowledge about human rights, with a particular focus on teachers and key personnel in the justice sector, civil society and the media.

3.3 The rule of law and legal safeguards

True freedom requires the rule of law and justice, and a judicial system in which the rights of some are not secured by the denial of rights to others.

Jonathan Sacks

Human rights, democracy and the rule of law are closely related and mutually dependent. Respect for human rights is crucial to democracy; but at the same time, human rights are merely empty words without institutions to ensure that they are upheld and properly protected. These institutions include courts, the police, national assemblies, national human rights institutions and monitoring bodies to oversee the implementation of human rights.

Figure 3.4 Massimo Dezzani, Italy

Legal protection is a key element of the rule of law. It means that individuals are protected against abusive or arbitrary treatment by the authorities. Legal protection should also ensure that individuals are safeguarded against violent acts committed by other citizens, for example through organised crime or terrorist acts. Individuals should enjoy predictability with regard to their legal status and be able to defend their legal interests.

3.3.1 Reinforcing the rule of law

A well-functioning legal system is vital for ensuring that human rights are respected, and for maintaining a true democracy. The right to a fair trial includes the right to be tried before impartial and independent judges and access to a defence counsel in criminal cases, adherence to the principle of hearing both sides of a case, and the right to a decision within a reasonable period of time. The right to a fair trial is a cornerstone of several of the global and regional conventions on human rights.

However, a number of countries do not have an independent judiciary. This is particularly the case in countries where respect for human rights is weak. The reasons for this are many, and include insufficient capacity, expertise and economic resources, as well as corruption, inadequate legislation, ineffective administration and political pressure. In some cases, the political pressure is so strong that the courts are seen as controlled by the authorities, and even used to suppress the opposition and human rights defenders. Another important factor is the economic, socio-cultural and psychological barriers that many people experience, especially in poor countries, where the only real opportunity to have their rights upheld is through other mechanisms, such as conflict resolution boards and ombudsmen. Local and national courts face particular challenges in cases where foreign interests are involved, such as cases involving international companies or criminal cases against foreigners.

The Norwegian authorities have built up experience in supporting institution building and strengthening the justice sector in partner countries. Norwegian efforts can help to build capacity and enhance the degree of independence of the court system, to strengthen independent national human rights institutions and monitoring bodies, and to fight corruption and the abuse of power. The Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security and the Norwegian justice sector have extensive experience in helping to develop the rule of law in a number of regions, particularly in the Middle East and the Balkans, but also in the Caucasus and Afghanistan and in connection with operations in Africa. The Crisis Response Pool is made up of personnel from the Norwegian justice sector who can be deployed to international organisations or in accordance with bilateral agreements. They provide advice and assistance in the development of independent courts, the rule of law and democracy.

Priorities:

promote fair and effective legal systems based on respect for human rights, particularly through training activities and cooperation at expert level within the justice sector;

help to enhance legal protection and transparency in the court system in individual countries, particularly through court observation and support for the courts administration;

help to develop national conflict resolution boards and monitoring bodies.

3.3.2 Combating torture and abolishing the death penalty

An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.

Mahatma Gandhi

The right to life is enshrined in both global and regional human rights conventions. The right to life and respect for human dignity and inviolability are underlying premises on which all other human rights and fundamental principles of the rule of law are based. The authorities must not only respect the right to life themselves, but also ensure that others do so, for example through the criminalisation and investigation of murder and the protection of citizens against terrorism. Use of the death penalty, torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment is a violation of these principles, and is in itself inhumane.

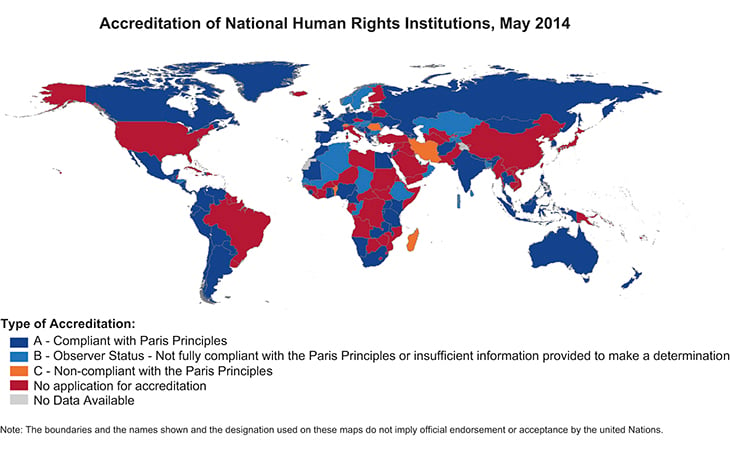

Figure 3.5 Accreditation of national human rights institutions as of May 2014. The Storting decided on 19 June 2014 that Norway should establish a new national institution for human rights, organised under the Storting, that is to be in operation from 1 January 2015.

Source Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

Despite an absolute prohibition on torture, it is still widely used. According to Amnesty International, the use of torture was documented in 112 countries in 2012.3 In many of these, torture is used systematically, i.e. it is accepted or even actively used by the country’s authorities themselves. Torture may be used to obtain a confession or information, as a punishment, as an act of discrimination, or to break down individuals by inflicting serious physical or psychological pain. In the fight against terrorism, the prohibition against torture has been violated in various parts of the world. For many years, the Norwegian authorities have supported the international effort to end torture, seeking both its prevention and the rehabilitation and treatment of torture victims.

Textbox 3.9 National human rights institutions

Since 1993, the UN General Assembly has recommended that states establish a national human rights institution (NHRI) in accordance with the Paris Principles.1 These principles are flexible standards, but they place particular emphasis on independence from national authorities. The main objective of a national human rights institution is to assist the public, NGOs and individuals by providing advice, reports and information on specific issues or individual cases relating to human rights. NHRIs can apply to the International Coordinating Committee for National Human Rights Institutions (ICC) for accreditation on the basis of compliance with the Paris Principles. NHRIs that are considered to fully comply with the Paris Principles are given ‘A’ status by the ICC. This is internationally recognised as a stamp of quality.

1 Principles relating to the Status of National Institutions, adopted by the UN General Assembly on 20 December 1993, by resolution 48/134.

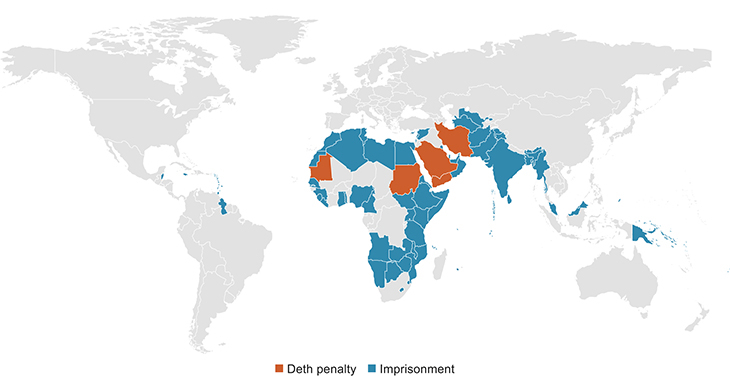

International death penalty trends lean towards abolition. In 1945, when the UN was established, only eight states had abolished the death penalty for all crimes. By 1977, the figure had risen to 16, and today approximately 160 of the 193 UN member states have abolished the death penalty either by law or in practice, according to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. However, in 2012 and 2013, there was an increase both in the number of countries that use the death penalty and in the total number of executions. Norway is playing a leading role in the international fight against the death penalty. When the death penalty is carried out in a particularly inhumane way or used against minors, pregnant women or persons who cannot be deemed criminally responsible, this is a clear violation of international law. So too is the use of the death penalty in cases where proper legal safeguards have not been ensured during the legal process, or in cases where it is used for actions that cannot be considered as the most serious crimes.4 The UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions defines the ‘most serious crimes’ as those involving intentional killing.5 The obligation of all states to combat extrajudicial executions and to ensure a fair trial in cases where the death penalty could be imposed is a key part of the obligation to protect the right to life.

The setbacks in the fight against torture and the death penalty in recent years highlight the need to sustain the efforts in this field.

Priorities:

work to ensure that all countries abolish the death penalty by law or introduce a moratorium on executions, and join an international ban of the use of the death penalty;

host the sixth World Congress against the Death Penalty in 2016;

promote full respect for the absolute prohibition against torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, including effective prevention in accordance with international rules.

3.3.3 Combating corruption

Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

Lord Acton

Corruption is one of the greatest obstacles to development and the realisation of democracy, the rule of law and human rights. Corruption makes it difficult to develop democratic institutions and undermines existing ones. It slows economic growth and destabilises societies. The purchase and sale of votes is incompatible with fair elections. When the police and courts accept bribes, legal protection is undermined, and the principle of equality before the law is violated when people have to make unofficial payments for public services they are entitled to. Economic development is slowed, as corruption discourages foreign investment and can result in impossible ‘start-up costs’ for small enterprises in the country concerned. Oversight and transparency in the public administration and government budgets are crucial in order to hold the authorities accountable and to ensure that political decisions and budget allocations are followed up. Respect for the right to insight and information is therefore important. Independent media can also play a key role in exposing corruption.

Textbox 3.10 Norwegian support for the rule of law in the Western Balkans

Support for the development of good governance, including the rule of law and justice sector reform, will continue to be a priority for Norway’s efforts in the Western Balkans. Justice sector reform will be crucial for ensuring the independence of the courts and the ability of these countries to effectively protect human rights. Without credible reforms in this area, these countries will not be able to meet the rule of law requirements for EU membership or comply with the European Convention on Human Rights. A sound justice sector in the region is also in Norway’s interest, as this will increase the effectiveness of cooperation on transnational crime, for example the fight against human trafficking. This is why the Norwegian authorities are providing experts to the EU Rule of Law mission in Kosovo (EULEX) through the Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM), among others.

Corruption is prohibited by Norwegian law, whether it takes place at home or abroad. The same applies, inter alia, to UK and US law. Corruption may directly cause violation of human rights such as protection against discrimination, equality before the law, freedom of expression and the right to a fair trial. Corruption can also threaten freedom of the press when media that help to expose unacceptable practices are subject to abuse of power. Individual journalists are often targeted, and newspapers, radio stations or other media may be partially or completely closed down.

Figure 3.6 Aditya Mehta, India

Although freedom from corruption is not set out as a separate human right, its status can be inferred from several international and national instruments, including the UN Convention against Corruption. Several Council of Europe conventions are also important in the fight against corruption, including the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption and the Civil Law Convention on Corruption and their additional protocols. The Group of States against Corruption was established by the Council of Europe to monitor states’ compliance with its anti-corruption standards.

The Government considers the fight against corruption as an important and integral part of its efforts to help other countries to establish systems to ensure good governance and to prevent, expose and prosecute cases of corruption. The Norwegian authorities are also at the forefront of efforts to strengthen the multilateral and regional organisations’ work in this field. Our main focus is on bilateral cooperation, work with the international business sector and efforts to promote financial transparency.

Priorities:

practise zero tolerance for corruption and other economic irregularities, including by requiring that payments from Norway are paid back and those responsible prosecuted in cases of corruption, and by considering a freeze on further aid in serious cases;

continue support for mechanisms and initiatives to fight corruption and increase transparency in public administrations, in particular financial transactions, including the mechanisms and initiatives established by the UN, the OECD, the Council of Europe and other relevant bodies, as well as the international financial institutions and various regional mechanisms;

help recipient countries boost their capacity to prevent and fight corruption, with a particular focus on support for institution-building, national quality assurance systems, training, transparency and control mechanisms.

3.3.4 Protection of privacy

The protection of privacy is part of the right to privacy, and is recognised in a number of human rights conventions at both global and regional level. Respect for and protection of privacy is a fundamental part of democracy and the rule of law. It includes individuals’ right to decide over their private life and personal data. Protection of privacy not only entails protecting individuals’ integrity and private life; it also makes it possible for everyone to take part in a free exchange of views and in political activities, and to be confident that neither the authorities nor others will register or store information about their communication with others, their movements, their interests or the opinions they have expressed. Protection of privacy is particularly weak in countries with inadequate legislation and capacity to ensure proper protection of the private sphere. Political will is also a key factor. Human rights defenders, journalists and others who may be perceived to be a threat to the established power structures are particularly, and increasingly, subject to surveillance and other violations of privacy.

Textbox 3.11 Initiatives to increase transparency and cooperation with civil society

In 2011, Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, Norway, South Africa, the Philippines, the UK and the US founded the Open Government Partnership (OGP). OPG is an international platform for countries wishing to modernise their societies, with particular focus on close cooperation between the authorities and civil society to improve the welfare of the population. This involves increasing the transparency of the public administration, including financial transactions and allocations, improving the quality of services provided by the public sector, and enhancing corporate social responsibility. A key element is transparency of revenue flows between the government administration and the various sectors, such as oil, gas and other natural resources. Another important element is transparency of development aid and the results achieved.

Each country participating in OGP is to draw up a two-year action plan to address its particular challenges. These action plans are to reflect the principles of open government – transparency, public participation and accountability – with emphasis on technology and innovation. The action plans, which are to be drawn up in consultation with civil society, are to be evaluated by an independent reporting mechanism. Civil society is also represented on the steering committee. The action plans can include both measures for the country concerned and measures involving other countries, for example using aid to enhance these countries’ ability to provide good services for their populations.

From 2011 to 2014, the number of countries participating in OGP increased from 8 to 65. Norway was on the steering committee from 2011 to September 2014. The Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation has been Norway’s contact point for OGP.

Norway is also a key supporter of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). The EITI Standard is a global transparency standard which requires that companies in the extractive industries publish what they pay in tax to the countries they are operating in, and that the authorities in those countries publish the amount of revenue they receive. Compliance with the EITI Standard is monitored by civil society. Transparency of payments means that people know more about what funds are available for public spending, and can more easily form an opinion as to how these funds should be spent. In resource-rich countries, the amounts may be huge. EITI is thus important both for the fight against corruption and for efforts to promote democracy.

The EITI secretariat is situated in, and receives economic support from, Norway. In September 2014, 46 countries were taking part in the EITI; 29 of these, including Norway, are compliant countries, and 17 are candidate countries. The Norwegian authorities will seek to encourage more countries to implement the EITI and comply with its standard.

Individuals’ right to privacy and to decide over their personal data is not absolute. Surveillance and information gathering may be necessary for security reasons, but must only be carried out in accordance with stringent legal safeguards, in order to avoid violating human rights. Interference with an individual’s privacy is only permissible when carried out in accordance with legislation, when there is a legitimate objective, and when this is necessary in a democratic society.

The protection of privacy is being threatened by the digitisation of society. We are all leaving extensive digital footprints, which singly or in combination can be sensitive. An increasing proportion of electronic communication is crossing borders, either directly between individuals in different countries, or indirectly when information for a recipient within the same country as the sender is transmitted via satellites or other technology that is situated in another country’s territory. Even though international human rights monitoring bodies have decided in several cases that the right to privacy also applies to cyberspace, international rules are generally not formulated to take this into account. The Government has set up a committee to map cyber security vulnerability and propose concrete measures to enhance preparedness and reduce vulnerability in Norway. The committee has also been mandated to describe the key restrictions under international law on gathering information from other countries and the relationship between the right to privacy and the gathering of information. The committee is to submit its report in September 2015.

Figure 3.7 Michael Salceda, Mexico

Norway is actively engaged in the international efforts to protect privacy in cyberspace. Norway is also taking part in the negotiations on the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, the aim of which is to protect citizens’ privacy and to create economic growth by facilitating cross-border trade. Cooperation with the private sector is also important in the work to ensure a free and open internet where the protection of privacy and other human rights are respected.

Priorities:

work to ensure the protection of privacy in cyberspace;

work to ensure that the protection of privacy is protected in national legislation and that interference with an individual’s privacy is subject to stringent legal safeguards.

3.3.5 The right to own property

The right to own property is enshrined in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but it is not regulated in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights or the International Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights. The right to own property is, however, regulated by several regional instruments, including the First Protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights. The right to own property can also be inferred to some extent from other human rights, such as the right to protection against discrimination and the right to a fair trial. Other property rights, including collective land rights and traditional land use rights (in particular grazing rights and the right to use uncultivated land, which are essential for nomadic peoples), are included in various regional conventions and conventions on specific matters.

The right to own private property is crucial to a genuine, effective market economy, and is also essential for realising economic, social and cultural rights, such as the right to adequate housing. The fact that many countries do not have a property register is a problem. Lack of clarity regarding ownership and user rights and inadequate legislation or follow-up and enforcement of legislation are among the factors preventing people in rural areas from working their way out of poverty. This is particularly the case for women. The Norwegian authorities have been at the forefront of efforts to reach agreement on the UN Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests. These guidelines are particularly important for upholding the land rights of poor farmers.

Another important human rights issue in this context relates to discrimination. In many countries, property rights, especially of women and vulnerable groups, are restricted. Discrimination may occur in connection with inheritance, buying a house, tax on real property, the award of licences, the sale of property, development projects or transfer of ownership of production facilities. The Government gives high priority to fighting all forms of discrimination, and will also focus on efforts to protect the right to own private property.

Priorities:

seek to ensure that national authorities promote and respect the right to own private property, particularly for women and vulnerable groups, both through legislation and in practice;

promote cooperation and exchange of experience in this field between Norwegian institutions and institutions in relevant countries.

Textbox 3.12 Clarification of property rights in the wake of conflicts and crises

Problems often arise in connection with the documentation and legal clarification of property rights following armed conflicts or humanitarian crises. Registration of ownership is important for the opportunity to take up a loan and for attracting investment, and thus creating new economic growth.

This can be seen, for example, in the Western Balkans in the wake of the 1990s wars. A great deal of documentation was lost or was taken when people were forced to flee their homes, and in connection with the legal situation after the dissolution of Yugoslavia. The Norwegian Mapping Authority has helped to secure property rights through registration of ownership and surveys of private property, business property and agricultural areas. Norwegian experts who have been deployed through the Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights (NORDEM) to the EU Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX) and Kosovo Property Agency have also helped to resolve property disputes that have arisen after the hostilities in Kosovo. The Norwegian authorities will also continue to support the efforts to strengthen economic rights in the Western Balkans.

Another example is the Philippines. When the typhoon Haiyan struck in November 2013, millions of people lost their homes. Many of those who were internally displaced have also been at risk of being evicted as a result of government measures in response to the disaster. NORCAP (the Norwegian Refugee Council’s emergency standby roster) has provided experts to support the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in its efforts to resolve these issues. Through negotiations with the local authorities, UNHCR has helped to prevent evictions and ensure that people have been able to return to their rightful homes.

3.4 Equality and equal opportunities

Democracy is not the law of the majority but the protection of the minority.

Albert Camus

Human rights apply to all people without distinction of any kind, such as gender, ethnicity, race, religion or belief, indigenous identity, sexual orientation or level of functioning. The preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 reaffirms the ‘dignity and worth of the human person’ and the ‘equal rights of men and women’. These are key principles for the norms that are set out in the Declaration. However, there is active resistance to these principles even today – nearly 70 years after the Declaration was adopted by the UN General Assembly. Again and again, majority groups misuse the opportunities provided by democracy to set aside the rights of minorities, racism continues to raise its head in all parts of the world, and groups that have suffered injustice for generations are still denied their rights. Some groups are in need of and entitled to special protection. Conventions have therefore been drawn up to protect the rights of specific groups, including women, children, refugees, people with disabilities and indigenous peoples, which elaborate on the more general provisions in the UN’s core human rights instruments.

Figure 3.8 Sze Hang Wai, Hong Kong/Kina

The Government intends to intensify its efforts to fight discrimination and improve the situation of vulnerable groups. This includes addressing multiple discrimination, i.e. discrimination on the basis of several factors. A key aim is that Norwegian efforts will enable the countries concerned to guarantee that all individuals can enjoy the same rights in practice.

Figure 3.9 Eric Le, Australia

Textbox 3.13 Discrimination based on caste

Caste-based discrimination is a major problem in countries with a caste system. An estimated 260 million people are affected, mainly in Asia and Africa. For example, sexual violence is used against low-caste women to maintain control over their caste, and to ensure ownership of all kinds of resources, from land to information. In areas where legal systems are ineffective, there are often no consequences for the perpetrators. Police officers from a low caste may be powerless to take action against perpetrators from a higher caste, incidents reported to the police are often not registered due to widespread corruption, and there are frequent reports of girls who go to the police to report rape, being raped again by police officers. Norway is seeking to draw more attention to the issue of caste in international forums.

3.4.1 Gender equality and women’s empowerment

The most important international instrument for promoting and protecting women’s rights is the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). CEDAW has been ratified by nearly all UN member states. The prohibition against gender discrimination is also enshrined in other key global and regional conventions. However, a number of states have entered reservations against important provisions, with reference to national legislation or religion. The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, adopted at the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995, is another key reference document for efforts to promote gender equality and women’s rights.

A huge number of women and girls are regularly subjected to threats and violence, including sexual violence and killings, and in many cases the authorities are unable or unwilling to take effective action. According to UNICEF, 125 million girls and women have undergone female genital mutilation, and between two and three million girls are at risk each year of being subjected to this harmful practice.6 Sex-selective abortion is on the rise. On average, women have less opportunity to participate in political life than men, and they are overrepresented in the informal economy. Worldwide, women receive just 10 % of the total income from employment and own just 1 % of all property.7 Women and girls often have less legal protection and poorer access to health services and education than men, and their physical safety is more often threatened. Women and girls from minority groups or with disabilities are particularly vulnerable.

The gender perspective is integrated into all areas of Norwegian foreign and development policy. Norway is at the forefront of efforts to reach global consensus on strong measures to promote gender equality and women’s rights, and is seeking to ensure that one of the Sustainable Development Goals focuses on this issue. One of Norway’s key messages is that greater implementation of women’s rights, including better access to resources and improved opportunities for women to exert an influence, is not only a goal in its own right, but also a driving force for sustainable development, eradication of poverty, the development of democracy, and lasting peace.

Textbox 3.14 Female genital mutilation

According to UNICEF, most of the girls and women who have undergone female genital mutilation live in countries in Africa and the Middle East, and one in five lives in Egypt.1 This practice continues despite the fact that most girls and women in the affected countries want it to be abolished. Fear of severe social sanctions and stigma are among the most common reasons why it is continued.

Female genital mutilation is a serious violation of the right to protection against discrimination and the right to protection against inhuman or degrading treatment, the right to development, and the right to the highest attainable standard of health. In the worst cases, the lives of these girls is at risk. Child marriage and early pregnancy are more frequent in areas where female genital mutilation is practised.

Effective methods for preventing female genital mutilation have been developed in recent years. These have all taken a rights-based approach that provides training in human rights, followed by an open dialogue and a collective decision to abolish the practice. Local ownership is crucial, but pressure also needs to be exerted through policy decisions made at a higher level, legislation, education and the media. The 2012 UN General Assembly resolution on intensifying global efforts for the elimination of female genital mutilations was a breakthrough, and has become an important global framework for efforts to abolish the practice. In 2014, the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution requesting the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to compile good practices and major challenges in preventing and eliminating female genital mutilation.

The Government aims to strengthen international efforts to combat female genital mutilation. It will seek to establish this work as a separate field, and ensure that it is integrated into efforts in other relevant areas, such as women’s rights and gender equality, education, health and human rights in general.

1 Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: a statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change, 2013.

Norway’s gender equality efforts take a broad approach that includes both women and men, regardless of ethnic background, age, sexual orientation or level of functioning. Everyone affected – and that means women and men, boys and girls – must be involved in the efforts to achieve gender equality.

Priorities:

further develop the leading role played by Norway in efforts to promote gender equality and women’s rights, including combating discrimination against women in legislation and practice;

seek to ensure that women are given equal rights to political and economic participation, including equal rights to enter into agreements and to own land and equal inheritance rights;

combat violence against women, in part by developing a strategy to fight female genital mutilation;

strengthen women’s right to health, including sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights, and promote international acceptance for sexual rights and for right to abortion.

3.4.2 Children

The Convention on the Rights of the Child sets out that all children have fundamental rights relating to survival, participation, development, and protection against discrimination. The Convention has been ratified by almost every country in the world, but a number of countries have made extensive reservations. There has been a positive development in recent years in key areas such as education and survival. However, the fact remains that 25 years after the Convention was adopted, a huge number of children are still living in conditions that are far below the standards set.

Textbox 3.15 Child marriage and forced marriage

According to UNICEF, an estimated 14.2 million girls under the age of 18 are forced into marriage every year. Today there are more than 700 million women who were married before the age of 18. A third of these women were under the age of 15 at the time of marriage. Some boys are also forced to marry young, but girls are disproportionately affected. In Niger, which has the highest incidence of child marriage in the world, 77 % of women aged 20–49 were married before the age of 18, in contrast to 5 % of men in the same age group. The same gender disparities are seen in countries where child marriage is less common. Child marriage among girls is most widespread in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Nearly half of the girl brides worldwide are from South Asia, and India alone accounts for a third. Bangladesh has the highest proportion of brides under the age of 15.1

Girls from poor families, girls living in rural areas and girls with the lowest levels of education are the most vulnerable. For many of them, marriage marks the start of sexual abuse, discontinued education, and high-risk pregnancies and childbirth. Child marriage is a violation of the rights enshrined in both the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

Norway is among the largest donors to the United Nations Population Fund, which is one of the most important global actors in the fight against child marriage. The Norwegian authorities also support other organisations that seek to prevent child marriage and forced marriage through education as well as health and human rights programmes.

1 UNICEF, Ending Child Marriage: Progress and prospects, 2014.

Figure 3.10 Maryla Rarus, Poland

The authorities in each country must be held accountable for realising children’s rights through legislation and the establishment of the necessary institutions. They must ensure that children and young people are protected against violence, abuse, exploitation, and recruitment to armed forces, and they must give priority to safeguarding children’s right to survival, development, health and education when allocating resources. It is important that measures target the poorest and most marginalised children, and that children and young people have the opportunity to participate, to express their opinions and to organise themselves in order to promote their interests and define their needs.

Empowering children and young people is a good investment, as it fosters the development of active citizens who can assert their social, economic and political rights. The Government’s intensified efforts to promote education will improve the realisation of children’s rights, such as their opportunity to participate, and will increase children’s awareness of human rights.

Priorities:

help to ensure that all children have the opportunity to start and complete school, and that all children and young people learn basic skills and are equipped to tackle adult life;

help to strengthen the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, for example by supporting organisations that promote children’s rights;

combat female genital mutilation, and help to improve children’s health and reduce child mortality;

seek to ensure that children are protected in armed conflict, and combat violence against children.

3.4.3 Persons with disabilities

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was adopted in 2006. The states parties to the Convention have committed themselves to combat discrimination and to promote inclusion in society at both national and international level. The Convention emphasises the principles of non-discrimination, accessibility and participation, and underlines the inclusion of persons with disabilities as an important element in promoting sustainable development. Norway became party to the Convention in June 2013.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that around one billion people have some form of disability, and has pointed out on a number of occasions that it will not be possible to achieve the Millennium Development Goals unless persons with disabilities are fully included in society.8 Persons with disabilities are often discriminated against and excluded from social, economic and political processes. They have lower than average scores on most standard-of-living indicators, and are more likely to live in poverty, tend to have less education, are less likely to be employed, and have poorer access to health and rehabilitation services than other population groups. These disparities are more marked in developing countries. Women and girls with disabilities often experience multiple discrimination, and are particularly vulnerable to abuse and violence. Children with disabilities are more likely than other children to be excluded, for example from education. The Government will therefore implement urgent measures to reach out-of-school children with a view to achieving the education targets in the Millennium Development Goals, and is advocating the inclusion of a target on rights-based education, with particular focus on marginalised groups, in the new Sustainable Development Goals.

The Norwegian authorities have given priority to improving the situation for people with disabilities. Norway is also seeking to ensure that this issue is moved further up the agenda in the UN and other multilateral forums, and supports the UN effort to make sure that all states implement the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Great importance is attached to supporting and involving people with disabilities, their organisations and voices of advocacy in the international community in this work.

Figure 3.11 Anna Wcislo, Poland

Priorities:

contribute to strengthening the implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, for example through aid for education, humanitarian aid, efforts to promote global health, and efforts to promote women’s rights and gender equality;

give priority to improved access to education for people with disabilities and be at the forefront of efforts to include the special needs of children with disabilities in bilateral and multilateral cooperation on education and in humanitarian education efforts;

increase support for victims of small arms, mines, cluster munitions and other explosives, and advocate that the prevention of injuries from such causes and the rehabilitation of victims are more widely recognised as human rights issues;

contribute to the development of concrete indicators that highlight the situation of people with disabilities, and thus help to ensure that their needs and rights are respected, protected and fulfilled.

3.4.4 Indigenous peoples

Indigenous issues are high up on the UN’s agenda. The establishment of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues and the appointment of the UN’s first Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples in 2001, the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, and the establishment of the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by the UN Human Rights Council in 2008 are important milestones in the international efforts to promote indigenous issues. In addition, the ILO Convention concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries (C169), which Norway was the first country to ratify in 1990, sets out important provisions on the right of indigenous peoples to maintain and further develop their cultures, and to be consulted on matters that affect them. The Convention also includes provisions on land rights, recruitment and conditions of employment, education and training, social security and health. Today, representatives of indigenous peoples take part in international processes where issues of relevance to them are dealt with. In September 2014, the World Conference on Indigenous Peoples unanimously adopted an ambitious outcome document that commits states to respect, promote and advance indigenous peoples’ rights. The outcome document was the result of an open and inclusive process, in which indigenous peoples had been actively involved.

Despite these positive developments in international forums, many indigenous people still live in very difficult conditions. In many countries, indigenous peoples are largely excluded from political, economic and cultural life, and indigenous groups have a lower score than other population groups on many standard-of-living indicators, for example health and education. Indigenous peoples are also particularly vulnerable to the impacts of global climate change and the increasing pressure on the world’s natural resources.

The indigenous peoples’ perspective is particularly relevant in Norway’s High North policy, in the Government’s International Climate and Forest Initiative, and in the work on business and human rights.

Priorities:

be at the forefront of the international effort to promote indigenous rights, by encouraging more countries to become party to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and ILO Convention 169, and promoting the implementation of these instruments;