6 Safeguarding threatened species and habitats

6.1 Introduction

Some of the Aichi targets are specifically intended to safeguard threatened species and habitats, particularly target 12, which states that ‘by 2020 the extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained’. Norway’s corresponding national target is that ‘no species or habitat types will become extinct or be lost, and the status of threatened and near-threatened species and habitat types will be improved’. The target refers to species extinction as a consequence of human activity, which does not exclude the possibility that species may be lost as a result of natural processes. Moreover, it follows from the management objectives for species and habitat types in the Nature Diversity Act that habitat and species and their genetic diversity are to be maintained within their natural ranges. All these goals are particularly relevant to threatened species and habitats, in other words species and habitats that Norway risks losing altogether. Neither the national target nor the management objective for species applies to alien organisms.

Ecosystems are complex, and we often lack information about the functions of individual species in an ecosystem and the interactions between them. In many cases, the impacts of species extinction or habitat degradation do not become apparent until some time after the damage has been done. On a number of occasions, species extinction or a severe population decline in a particular species has proved to have cascading effects on other species in the same ecosystem and to cause major changes in the ecosystem as a whole. This means that there are significant risks involved in putting so much pressure on species and habitats that they at risk of being wiped out. Communities and ecosystems have considerable adaptive capacity, but it is often impossible to know until afterwards whether or not a system will adapt successfully to change.

We know that climate change may result in rapid changes in ecosystems. If there is already a great deal of pressure on the environment, climate change may be a significant additional stressor. The risk of major ecosystem change will rise if the cumulative environmental effects of all pressures become too great. Such changes may also have substantial social consequences. Action to safeguard threatened species and habitats will reduce the risk of their loss, and thus prevent possible consequences of their loss that cannot be foreseen.

It is also vital to safeguard species and habitats in order to give future generations the opportunity to utilise resources from nature, including those whose potential is currently unknown.

The Government’s proposals in Chapter 5 of this white paper are intended to ensure sustainable use and achieve or maintain good ecological status in Norway’s ecosystems. This is important for threatened species and habitats as well. However, it will often be necessary to take more specific and clearly targeted action in addition to safeguard species and habitats that are at serious risk. International commitments relating to specific species or habitats may also mean that Norway is required to take appropriate action. If a significant proportion of the population of a species or the area of habitat type is found in Norway, and action in Norway can improve its conservation status globally or at European level, this can also be an important reason for Norway to take stronger action.

In this chapter, the Government proposes measures to safeguard threatened species and habitat types. These include both conservation measures to protect species and habitats, and action to reduce the pressures and impacts associated with individual developments. Chapters 6.2 and 6.3 describe the Government’s general proposals for safeguarding threatened species and habitat types respectively, while Chapter 6.4 contains more specific proposals for the different major ecosystems. The Government also sets out general principles for selecting which tools and instruments to use in Chapters 6.2 and 6.3. Before a decision is made on which tools and instruments to use to safeguard a specific threatened species or habitat, an assessment of any significant economic and other effects will be carried out in the normal way, together with a public consultation. The effects of the action to be taken may vary widely depending on what it is intended to safeguard and what kind of restrictions on use it may involve. After this, the need to safeguard the threatened species or habitat, the value of associated ecosystem services and the effects on other public interests (as specified in section 14 of the Nature Diversity Act) will be weighed against each other to determine whether to apply the proposed tools and instruments. It is important to target the action taken precisely so that species and habitats are given adequate protection without restricting other activities that are beneficial to society more than necessary. Tools and instruments to safeguard threatened species, habitats and ecosystems should promote coordination and sound use of resources across sectors.

Chapter 6.5 deals specifically with action to safeguard genetic resources.

6.2 Safeguarding threatened species

To prevent the loss of species, the Government will continue to use both species-based measures such as regulating harvesting, protecting individual species, designating priority species and establishing quality norms, and area-based measures that are intended to safeguard areas with specific ecological functions for a species. The latter include protecting areas under the Nature Diversity Act, identifying areas with specific ecological functions for priority species, designating selected habitat types, and sectoral measures. The Government will also seek to prevent the loss of species by re-establishing populations and through gene banks and breeding programmes.

The Government will seek to improve the conservation status of threatened species. This is a long-term effort. The Government’s first priority will be to improve the conservation status of species that are critically endangered or endangered in Norway and that meet the additional criterion that either a substantial proportion of their European population is found in mainland Norway or in Svalbard, or they are threatened globally or in Europe as a whole. There are population targets for the four large carnivores (wolf, bear, lynx and wolverine) and golden eagle, which are used in the management of these species.

In all, the Norwegian Red List of Species contains 1120 critically endangered and endangered species, and for 78 of these, 25 % or more of the European population is believed to be found in Norway. They are mainly plants, fungi and lichens and a number of insects and arachnids, but they also include two fish species (spiny dogfish and golden redfish) and four mammals (hooded seal, wolverine, narwhal and bowhead whale). Most of them are associated with forest, cultural landscapes and mountains, and some with wetlands and marine and coastal waters. The largest numbers of critically endangered and endangered forest species are lichens (13 species) and fungi (11 species). Of the 26 mountain species, 16 are vascular plants, and they are primarily believed to be under pressure because of climate change. There are five marine species, the two fish species and three of the mammals. Since many of the 78 species are mainly mountain species, many of them are found in the counties that include a large proportion of mountain areas: Oppland (23 species), Sør-Trøndelag (23 species), Troms (18 species) and Finnmark (18 species).

Of the critically endangered and endangered species in Svalbard, there are six vascular plants and one lichen where 25 % or more of the European population is believed to be found in Norway.

Seventeen of the species that are critically endangered or endangered in Norway are in addition threatened globally or at European level. They include plants, insects, lichens, fish, birds and mammals. In six cases, 25 % or more of the European population is also believed to be in Norway. The six species are a bee, Osmia maritima, wolverine, golden redfish, boreal felt lichen (Erioderma pedicellatum), hooded seal and spiny dogfish.

In the Government’s view, the most appropriate approach for the majority of critically endangered and endangered species will be to use area-based measures that target habitats for a number of species simultaneously, for example protection under the Nature Diversity Act or designation of selected habitat types. Area-based measures will also be the most important approach for most other threatened species. Species-based measures will be used where a species needs protection against direct exploitation or strict protection is needed. It is essential to assess what is the most effective and appropriate approach before selecting the measures to implement.

Figure 6.1 The lapwing is now red-listed as endangered in Norway, after a substantial population decline in recent years. The main reason for the decline is changes in agricultural practices.

Source Photo: Bård Bredesen/Naturarkivet

Certain habitats, often called hotspots for threatened species, support large numbers of threatened species. By protecting these habitats it is possible to safeguard a number of threatened species simultaneously. Thus, area-based measures targeting hotspot habitats are generally a more appropriate way of safeguarding threatened species than measures targeting individual species, provided that the main threat to a species is not harvesting or other removal. The Government will therefore consider establishing protected areas under the Nature Diversity Act to cover areas that are hotspots for threatened species. Habitat types for which this may be appropriate are further discussed in Chapter 6.4 for each ecosystem.

When areas are protected under the Nature Diversity Act, landowners and holders of rights are entitled to compensation from the state for financial losses incurred when protection makes current use of the property more difficult. The exact restrictions on the use of an area must be assessed on a case-by-case basis when specific protection proposals are presented, as mentioned in Chapter 6.1. There is already an established system for voluntary protection of forest areas, and voluntary protection should also be tested in other ecosystems. Protection of areas under the Nature Diversity Act is further discussed in Chapter 6.4 for each ecosystem.

Habitats that are important for threatened species can also be designated as selected habitat types under the Nature Diversity Act. The Government will make use of this option if there are so many remaining patches of a particular habitat type that giving other public interests priority in some of these patches will not have a significant bearing on the conservation status of the threatened species associated with the habitat. One solution that will be considered for such habitats is to use the Nature Diversity Act to give statutory protection to some habitat patches, while others are safeguarded by designation as a selected habitat type. In other cases, it may be appropriate to use a combination of sectoral measures and the Planning and Building Act, perhaps combined with the designation of selected habitat types, if this gives adequate protection.

The provisions of the Nature Diversity Act on marine protected areas and selected habitat types apply in Norway’s territorial waters, in other words out to 12 nautical miles beyond the baseline. During work on the management plans for Norway’s sea areas, particularly valuable and vulnerable areas have been identified, many of which are at least partly outside Norway’s territorial waters. Some of these areas are important for threatened species. The need for measures to safeguard threatened species in these areas (under the management plans or other legislation) must be assessed in the light of the cumulative environmental effects on threatened species and habitats and how these are changing, for example as a result of climate change, ocean acidification and new activities.

The Svalbard Environmental Protection Act applies to the entire land area of Svalbard and its waters out to the territorial limit, subject to the limitations imposed by international law, and includes provisions both on species-related measures and measures relating to areas with specific ecological functions for different species. Fishery policy instruments are also important for the marine ecosystem around Svalbard.

In some cases, areas with specific ecological functions for a species are threatened because they are no longer used, which may for example result in open landscapes becoming overgrown. Here, the Government’s primary approach to conservation will be to use economic instruments such as grants towards grazing or active management, if appropriate combined with designation of selected habitat types. Private contracts may be an important supplement in such cases, particularly if few landowners are involved.

If area-based measures are not sufficient to ensure the survival of a species or are not the most appropriate or effective approach, the Government will consider the designation of priority species under the Nature Diversity Act. This makes it possible to prohibit all removal of, damage to or destruction of the species in question. As mentioned above, the Government will first consider this option for endangered and critically endangered species that have a substantial proportion of their European population in Norway. In doing this, the Government will also be meeting the Act’s requirement for the authorities to consider the designation of priority species in cases where there is evidence that the population status or trends for a species are substantially contrary to the management objective for species.

Designation of priority species is a suitable approach if there are direct threats to populations or stands of a species or to areas with specific ecological functions for the species. In particular, this approach will be considered for highly mobile species that range over considerable distances, where protection of their entire range would be too far-reaching, but certain areas with specific ecological functions, for example breeding sites for birds, can be protected. This may be an appropriate approach for both bird and mammal species. Designation of priority species will also be considered if statutory protection of the habitat would be an unnecessarily strict approach to safeguarding the species or if a species is found in many small habitat patches and area-based measures would not be effective. Area-based measures such as the establishment of protected areas will particularly be considered for species that are found in more clearly delimited habitats, such as plants, lichens and fungi, or if species-based approaches are not practical, for example for certain insect species. In some cases, designation of priority species will be the most appropriate measure for ensuring long-term survival.

The group of threatened species that is the Government’s first priority for improvements of conservation status is defined at the beginning of Chapter 6.2. It is likely that after a further assessment of these species, only a minority of them will be found to be best served by designation as priority species. This is because many of them are plants, insects, lichens and fungi, and habitat conservation will be more appropriate.

Protection by regulations under the Nature Diversity Act is a suitable way of safeguarding species of plants, fungi and invertebrates that are mainly threatened by harvesting or other removal. However, most such species are already protected under the existing regulations. Terrestrial mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians (collectively called wildlife species) are protected unless designated as game species. Wildlife species, salmonids and freshwater fish and marine species that are threatened by harvesting will be safeguarded by means of stricter restrictions on harvesting and on the use of fishing gear and other equipment, or if necessary by prohibiting harvesting, until their stocks recover. For example, no fishing is currently permitted for European eel, blue ling or golden redfish (see Chapter 6.4.1). In some cases, a longer stock rebuilding period may be accepted after consideration of other important public interests.

The report on experience of the application of the Nature Diversity Act (see Chapter 5.2) shows that there is so far little information on what effect designation as a priority species has in practice. Monitoring results are available for some species, for example the Arctic fox. The Ministry of Climate and Environment will continue these monitoring programmes. The Ministry will follow population trends for priority species generally, and the effects of designating priority species will be assessed after the system has been operative for some years. As far as possible, this assessment will be based on monitoring data.

Regardless of other action and policy instruments, the presence of threatened species and their habitats will be an important consideration in decisions about matters that may have a negative impact on these species, for example in planning processes under the Planning and Building Act and decisions under sectoral legislation. During the decision-making process, the degree of threat to a species must be weighed against other public interests. The more seriously threatened a species is, the more weight must be given to the management objective for species set out in the Nature Diversity Act. Each sector is responsible for incorporating this approach appropriately into sectoral legislation and guidance.

Transport projects can have serious negative impacts on threatened species in the area affected, and the transport authorities will further develop routines and guidance for the sector. For example, guidance on the environmental impact assessment of road projects will be updated.

Environmental crime also adds to pressures on a number of threatened species. The inspection and enforcement work of the Norwegian Nature Inspectorate and targeted use of the environmental coordinator system in the police service facilitates the exposure of such crime so that it can be prosecuted. Norway will continue its efforts to combat fisheries crime at national and international level.

Action on climate change, ocean acidification and long-range transport of pollution does not come within the scope of this white paper, but will in many cases also be very important for safeguarding threatened species and habitats. Other conservation measures may increase species’ resilience to climate change. The Government will assess adaptation of the nature management regime to boost resilience.

To safeguard threatened species, the Government will:

Make use of statutory protection and the designation of selected habitat types and priority species under the Nature Diversity Act to provide long-term safeguards for threatened species and areas with specific ecological functions for these species. In the first instance, these measures will be used to improve the conservation status of species that are critically endangered or endangered in Norway and that meet the additional criterion that either a substantial proportion of their European population is found in Norway, or they are also threatened globally or in Europe as a whole.

Ensure that the situation of threatened species is taken into account when central government authority is exercised, for example in decisions under sectoral legislation, when adopting central government plans under the Planning and Building Act, and when allocating grant funding.

By providing guidance and in other ways, encourage the counties and municipalities to take the situation of threatened species into account when exercising their authority, for example when adopting plans under the Planning and Building Act, making decisions under sectoral legislation and allocating grant funding.

Consider the implications of climate change and ocean acidification for the management of threatened species, and adapt the management regime accordingly.

Take steps to improve cooperation between the police and the inspection and enforcement authorities.

6.3 Safeguarding threatened habitats

As is the case for threatened species, the choice of measures to safeguard threatened habitats will depend on the range of pressures and impacts affecting a particular habitat type.

Unlike populations of a species, which can often recover if the right types of measures are chosen, an area of threatened habitat that is destroyed is often lost for ever. Re-establishing an area of habitat is much more costly than preventing its degradation, and designation of selected habitat types is one approach that can be used to avoid serious negative trends for habitats. Norway currently has a list of 40 habitat types that are considered to be threatened (i.e. have been placed in one of the categories critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable). Many of them are also important habitats for threatened species.

The Government will use protection of areas and designation of selected habitat types under the Nature Diversity Act, combined with sectoral legislation and grant schemes, to safeguard threatened habitat types. Statutory protection of areas will be considered if there are very few remaining patches of a habitat type and for habitat patches where ecological status is particularly good.

If the main threat to a habitat type is one particular activity that can be restricted tightly enough and over the long term using the relevant sectoral legislation, this approach will often provide good enough safeguards.

The Nature Diversity Act provides the legal authority for designating selected habitat types. One of the important factors when deciding whether to designate a selected habitat type is whether the status or trends for the type in question are contrary to the Act’s management objectives for habitat types. The Government will consider the possibility of designation of selected habitat types for each of the threatened habitat types. Under the Nature Diversity Act, special account must be taken of selected habitat types when conservation interests and other public interests are weighed against each other during decision-making processes. The different interests are considered within the framework of the relevant sectoral legislation. Designation of selected habitat types is therefore generally a good cross-sectoral instrument. In addition, the Government considers it positive that this is an instrument that promotes local autonomy and opportunities for municipalities to safeguard habitats through their land-use planning processes. The Government also emphasises the importance of assessing the suitability of selected habitat designation on a case-by-case basis. One element of this assessment should be to consider whether it is possible to integrate the process of weighing up conservation interests against other public interests for selected habitat types into sectoral instruments, either legal or economic instruments or both, or sectoral planning tools.

Designation of selected habitat types can also be useful in the case of habitat types that are threatened because they are no longer being used and actively managed. One proviso is that there must be other measures that can be used to encourage active management, for example grant schemes for maintaining cultural landscapes or threatened habitat types. Funding is limited, but within the framework of each grant scheme and the other considerations to which it gives weight, it is possible to give higher priority to the most valuable areas of a habitat type and to areas where private stakeholders are interested in carrying out habitat management with support from the public sector. Designation of a selected habitat type does not oblige the authorities to provide funding, but such habitats are likely to be given priority when funding is allocated. The presence of patches of selected habitat types will also be an important consideration if there is a possibility of land-use change at a later date.

Another important consideration for the Government is whether there are so many patches of a habitat type that the loss of some of them is considered to be acceptable. The size of the habitat patches may be another element of the assessment. Designation as a selected habitat type may for example be useful if there are many small habitat patches, and it would not be effective to carry out comprehensive protection procedures for all of these. It can also be a useful tool for larger areas, especially since the requirement to take special account of selected habitat types does not necessarily mean that the whole area must be protected. The management regime for selected habitat types does not prohibit a range of activities in the same way as the rules for protected areas established under the Nature Diversity Act. How a selected habitat type should be safeguarded will depend on what kind of threat there is to the habitat type and whether activities carried out in accordance with sectoral legislation can be adapted to take account of this.

When designating selected habitat types, the Government will also consider whether all areas of a habitat type should be included, or only those of highest ecological status. Important considerations here will be whether there are so many patches of the habitat type that only the best of them need to be included, and whether it is realistic for example to give priority to funding for habitat management for all of them. If there are relatively few high-quality habitat patches, but there is considerable potential for improving ecological status at other sites by habitat management, this should also be taken into consideration.

The report on experience of the application of the Nature Diversity Act (see Chapter 5.2) shows that there is so far little information on what effect designation as a selected habitat type has in practice. Some information to supplement the report can be obtained from statistics on the number of localities where habitat management is being carried out with funding through the grant scheme for threatened habitats. For example, in 2015 grants for habitat management were awarded for 560 (of 1275) of the traditional hay meadow localities. Hay meadows have been designated as a selected habitat type. In most cases, long-term agreements have been concluded with the landowners. The Ministry of Climate and Environment will continue to monitor trends in selected habitat types, and the effects of designating selected habitat types will be assessed after the system has been operative for some years. As far as possible, this assessment should be based on monitoring data.

Regardless of other action and policy instruments, the presence of threatened habitats will be an important consideration in decisions about matters that may have a negative impact on these habitats, for example in planning processes under the Planning and Building Act and decisions under sectoral legislation. During the decision-making process, the degree of threat to a habitat must be weighed against other public interests. The more seriously threatened a habitat type is, the more weight must be given to the management objectives for habitats in the Nature Diversity Act when decisions are made under other legislation. Each sector is responsible for incorporating this approach appropriately into sectoral legislation and guidance.

Projects in the transport sector can have serious negative impacts on patches of threatened habitat types, and the transport authorities will further develop routines and guidance for the sector so that adverse impacts can be assessed and avoided.

In some cases, the main threat to a habitat type will be climate change, ocean acidification or other types of large-scale environmental change. This is particularly true of some polar and alpine habitats, but climate change is expected to become a growing threat in other regions as well. The Government will therefore assess adaptation of the nature management regime so that other measures can be used to boost the resilience of threatened habitat types to such pressures.

To safeguard threatened habitats, the Government will:

Consider designating threatened habitats as selected habitat types where this is considered to be an appropriate approach.

Make use of statutory protection under the Nature Diversity Act if there are very few patches of a threatened habitat or their ecological status is particularly good.

Use sectoral legislation where appropriate to take action, both of a long-term nature and as a rapid response where necessary, to safeguard habitats that are mainly threatened by one particular activity.

Ensure that the situation of threatened habitats is taken into account when central government authority is exercised, for example in decisions under sectoral legislation, when adopting central government plans under the Planning and Building Act, and when allocating grant funding.

By providing guidance and in other ways, encourage the counties and municipalities to take the situation of habitats into account when exercising their authority, for example when adopting plans under the Planning and Building Act, making decisions under sectoral legislation and allocating grant funding.

Consider the implications of climate change and ocean acidification for the management of threatened habitats, and adapt their management accordingly

6.4 Safeguarding threatened species and habitats in each of Norway’s major ecosystems

6.4.1 Marine and coastal waters

Threatened species and habitats in marine and coastal waters are safeguarded in various ways, based on both sectoral instruments and environmental policy instruments. Threatened marine species and habitats are an important element of the work on the management plans for Norway’s sea areas. Based on experience gained from the designation of dwarf eelgrass (Zostera noltei) as a priority species, the Government will assess which other threatened marine species should be safeguarded in the same way. A review is to be carried out to determine which threatened marine habitats should be designated as selected habitat types. The establishment of marine protected areas under the Nature Diversity Act or sectoral legislation for a representative selection of marine habitats (see Chapter 7.3.1) will be important in safeguarding marine habitats and species. Chapter 5.2 discusses the geographical scope of the Nature Diversity Act, which delimits where these measures can be used.

Norway has a knowledge-based fisheries management regime, which is intended to ensure that the framework for commercial fisheries is as sustainable as possible. Directed fisheries for threatened species including European eel, blue ling and golden redfish have been closed. Most of the other threatened fish species are sharks, skates and rays. Although no direct fishery is permitted for these species, bycatches in other fisheries are a threat to several of them. The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries will continue efforts to survey the scale of bycatches and reduce bycatches of threatened species. Further knowledge will be built up on stocks, fishing techniques and fishing gear so that bycatches of threatened species and damage to threatened habitat types can be reduced. Bilateral and international cooperation is essential to ensure that shared stocks are fished sustainably, and Norway will continue to give high priority to such cooperation. Cooperation with Russia and the EU on the management of shared stocks is particularly important. The Government will also consider whether further improvements to the status of threatened fish species can be achieved through action on the basis of other sectoral instruments. Monitoring and a ban on harvesting will be continued for threatened whale species.

Norway’s seabird populations are changing; many are declining steeply, but not all of them. Norway has internationally important populations of a number of seabirds, and has a special responsibility for the populations of fulmar, cormorant (subspecies Phalacrocorax carbo carbo), shag, king eider, common gull, lesser black-backed gull (subspecies Larus fuscus fuscus), glaucous gull, great black-backed gull, ivory gull, Brünnich’s guillemot, little auk, black guillemot and puffin. More than 25 % of the European breeding population of all of these species is found in Norway.

A number of Norway’s seabird populations are threatened, and action needs to be taken to give them better protection. It has been pointed out that management measures at two levels need to be considered – both measures that target threatened seabird populations directly, and ecosystem-based measures, where seabirds are considered as an integral part of the ecosystem.

Measures that target threatened populations directly can include action to reduce pressures such as predation (for example by mink), unwanted bycatches and disturbance. These must be adapted to different species and sites to make them as effective as possible. Action to reduce the mink population along the shoreline and on coastal islands and skerries will be intensified. Surveys of bycatches and efforts to reduce the scale of seabird bycatches in the fisheries will be continued. For example, the introduction of specific requirements relating to gear and catch methods will be considered in fisheries or areas where bycatches of seabirds are a problem.

Apart from measures to safeguard threatened populations, management measures for seabirds should primarily form part of an ecosystem-based management regime. It is essential to ensure that seabirds, and many other predators in marine ecosystems, have adequate food supplies in the form of small plankton-feeding fish (fish larvae and small schooling fish species) and larger zooplankton such as Arctic krill species. In coastal waters, healthy kelp forests are vital for seabirds and other biodiversity and biological production.

As part of the follow-up to the white paper on the first update of the Barents Sea–Lofoten management plan (Meld. St. 10 (2010–2011)), unintentional bycatches of seabirds during longlining for Greenland halibut and gill netting for lumpsucker have been systematically registered. The aim is to quantify unintentional bycatches of seabirds and review possible preventive measures.

Norway has an extensive monitoring system for marine ecosystems, and has also developed a good seabird monitoring programme. These must be maintained to provide information on status and trends for populations of marine species, and the results must be linked to knowledge developed about the factors that affect seabird populations and the effect of measures to safeguard them. Long time series of data are vital to this work. Long-term mapping and monitoring of seabirds is organised through the SEAPOP programme, which also includes studies of the areas used by seabirds at different times of year. The Government will continue and further develop systematic mapping and monitoring of seabird populations in all Norway’s sea areas through the SEAPOP programme. The development of knowledge about seabirds and their food supplies will continue, and measures that can improve food availability for seabirds will be assessed. This work will involve cooperation between seabird experts, marine scientists and the public administration.

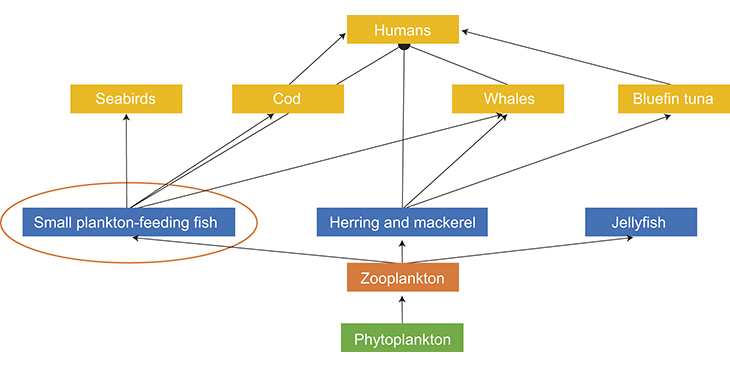

Figure 6.2 A marine food web

Simplified illustration of a marine food web. Small plankton-feeding fish (fish larvae and small schooling fish species) and larger zooplankton species (krill and amphipods) play a key role in energy flow through the ecosystem to higher trophic levels – larger fish, seabirds, marine mammals and humans. Ecosystem-based management is vital for maintaining ecosystem integrity.

The Pacific oyster is an alien species in Norway, and is a new and growing threat to the European flat oyster in Norway. The Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre has assessed the Pacific oyster and considers that there is a very high risk that it will displace native Norwegian species. The Government will complete and implement an action plan for containing and controlling the Pacific oyster.

The most seriously threatened of Norway’s marine habitats at present is sugar kelp forest, and its ecological status is particularly poor along the Skagerrak coast. This is believed to be due to higher inputs of nutrients and more sediment deposition combined with climate change, which is resulting in higher runoff of nutrients and particulate matter from land. Action to improve the situation will include measures that are part of the river basin management plans and, where relevant, measures in municipal action plans for climate change adaptation. The Government will also review other possible measures for reducing inputs of nutrients and particulate matter to important sugar kelp areas, including climate change adaptation measures for extreme precipitation events. A pilot project to re-establish sugar kelp forest will be initiated. International cooperation is also of crucial importance.

There are substantial inputs of nutrients to the Norwegian Skagerrak coast with ocean currents. Norway will continue to give high priority to environmental cooperation with the North Sea and Baltic Sea countries, including cooperation within OSPAR and the EEA Agreement.

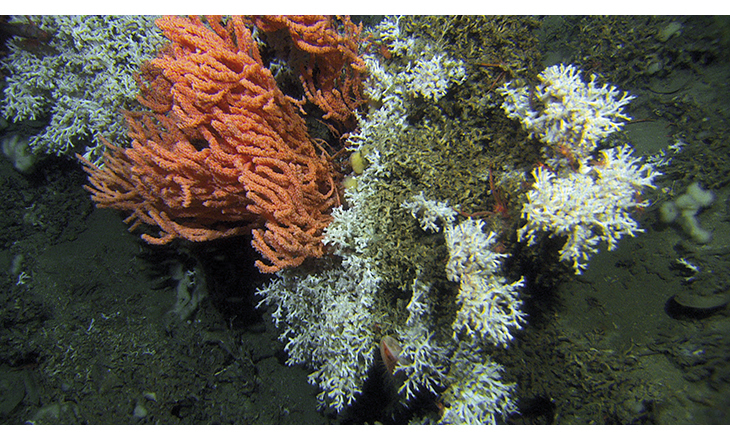

The Government will also intensify efforts to protect threatened marine habitats including cold-water coral reefs, which are particularly vulnerable to physical damage, sediment deposition, climate change and ocean acidification. Nine coral reefs have already received special protection against fishing using gear that is towed along the seabed. Work is in progress to protect more coral reefs in this way, and a public consultation on proposals to protect 10 more areas was held in 2015. The aim is to establish new protected areas in 2016.

Figure 6.3 A new reef complex was discovered off Sandnessjøen (Nordland) in autumn 2015. Two of the species that form the reef, the stony coral Lophelia pertusa (white) and the gorgonian Primnoa resedaeformis (orange) can be seen here. Banning bottom trawling is one important way of safeguarding coral reefs.

Source Photo: MAREANO/Institute of Marine Research

The environmental and fisheries authorities will together evaluate how instruments and measures in the two sectors contribute to the conservation of marine habitat types and whether further measures should be implemented.

The environmental and fisheries authorities will also evaluate how information on threatened marine habitats should be made available to and utilised by user groups. This can help to ensure that adequate information is available during activities such as commercial fisheries. The evaluation will specifically include information about the distribution of coral habitats.

In the petroleum sector, requirements to map coral reefs and to take steps to prevent sediment deposition and physical damage to coral reefs and other benthic communities help to prevent damage to threatened marine habitats.

It is important to continue mapping programmes and build up knowledge about cumulative environmental effects in order to address pressures and impacts associated with the fisheries, petroleum industry and other activities. Management of the marine environment will be based on the best available knowledge about cumulative environmental effects in order to safeguard threatened species and habitats as effectively as possible.

The marine management plans also focus on the conservation of threatened species and habitats. In addition, relevant sectoral legislation contains provisions that are important in protecting threatened species and habitats against pressures and impacts associated with activities such as fisheries, the petroleum industry and maritime transport. The Government will give weight to safeguarding threatened marine species and habitats in the further development of the management plans for Norway’s sea areas.

6.4.2 Rivers and lakes

The Water Resources Act and the Watercourse Regulation Act are important tools for safeguarding threatened species and habitats in river systems, both when new developments are planned and when taking steps to improve ecological status in rivers where there are already hydropower developments. When hydropower licences are revised in the years ahead, it will be important to look at possible ways of improving conditions for threatened species and habitats that are affected by hydropower developments. The competent authorities will also make more active use of the option of requiring licensing of older non-licensed hydropower developments to reduce damage to threatened species and habitats. In addition, the energy authorities and the environmental authorities will make more active use of the standard nature management conditions in licences to require action to reduce damage to threatened species and habitats.

No fishing for eels is permitted in Norway because there is concern about the population status of the species in Europe as a whole. Other methods of reducing the negative impacts of human activity on eels have also been reviewed, including steps to reduce barriers to migration in rivers. The environmental authorities, in cooperation with other relevant authorities, will consider how to respond to the proposals in the review.

In line with the general principles for selecting tools and instruments to safeguard threatened species and habitats set out in Chapters 6.2 and 6.3, the Government will use a combination of designation of selected habitat types and protected areas, as well as relevant sectoral legislation and the Planning and Building Act, to safeguard threatened habitats and habitats that are important for threatened species in rivers and lakes. These include inland deltas, oxbow lakes and other features of meandering rivers, large sand and gravel banks, the spray zone near waterfalls, calcareous lakes and lakes and ponds that are naturally free of fish. The Government will give priority to areas that are already protected against hydropower developments or where it is not realistic for other reasons to carry out hydropower developments. Calcareous lakes have already been designated as a selected habitat type, and the Government will consider the establishment of protected areas as a supplement for certain of these lakes. Oxbow lakes and other features of meandering rivers are considered to be particularly poorly served by conservation measures so far, given their significance for several important species groups. The Government will therefore give priority to these habitats. The establishment of protected areas in freshwater habitats is also discussed in Chapter 7.3.2.

The Government will continue measures that have been initiated to deal with particularly invasive alien organisms in Norwegian rivers and lakes. These include action to deal with signal crayfish, pike (outside its natural range) and Canadian and Nuttall’s pondweeds. Information activities are also important for preventing the illegal release of fish and avoiding the spread of invasive organisms with boats and fishing gear.

In addition to land-use change, pollution puts pressure on threatened species in rivers and lakes. Acidification, nutrient runoff from agricultural areas and industrial releases can all have negative impacts, either separately or in combination. The Government will therefore continue its efforts to prevent pollution from harming threatened freshwater species.

6.4.3 Wetlands

Pressures on wetland species and habitats are largely associated with various forms of land conversion and land-use change or with pollution. In line with the general principles for selecting tools and instruments to safeguard threatened species and habitats set out in Chapters 6.2 and 6.3, the Government therefore considers that area-based measures will be the most important approach to safeguarding threatened wetland species and habitats. They will also make a contribution to climate change adaptation.

In accordance with its general policy for threatened species and habitats, see Chapters 6.1 and 6.3, the Government will in the case of wetland ecosystems particularly consider the protection of selected breeding, staging and moulting areas for critically endangered and endangered bird species. In some cases, it may be appropriate to designate priority wetland species, see the criteria for this in Chapter 6.2. The Government will also consider protection under the Nature Diversity Act for selected lime-rich lowland mires, which are particularly important for threatened species. To safeguard patches of threatened wetland habitats that are not given statutory protection under the Nature Diversity Act, the Government will consider the designation of selected habitat types. Further, the Government will give priority to habitat management in protected wetland areas in order to improve the conservation status of threatened species, and will continue and step up peatland restoration as a climate policy and biodiversity measure, both within and outside protected areas. Peatland restoration can also help to improve the conservation status of threatened species.

Hay fens are a threatened habitat and already designated as a selected habitat type. The Government will continue existing grant schemes so that more sites can be safeguarded, and will monitor trends in land use for this habitat type and assess whether stricter protection of a large number of sites is necessary.

The Government will consider the designation of more threatened wetland habitats as selected habitat types, particularly raised bogs, ombrotrophic mires near the coast, lowland spring fens and active marine deltas. Conservation measures for palsa mires are considered to be adequate provided that the county conservation plan for wetlands for Finnmark is implemented, see Chapter 7.3.3. Further protection measures would probably not safeguard the palsa mires any more satisfactorily, since they are threatened mainly by climate change.

6.4.4 Forest

Many of the critically endangered and endangered species associated with forests belong to species groups that are found in fairly clearly delimited habitats. The main threats are related to land use (forestry) and land conversion, not to harvesting and other removal. In line with the general principles for selecting tools and instruments to safeguard threatened species and habitats discussed earlier, suitable approaches for safeguarding threatened forest species are area-based measures such as establishing protected areas, setting aside key biotopes that are not to be felled, and designating selected habitat types and priority species (together with areas with specific ecological functions for these species).

Key biotopes that are set aside and not felled safeguard habitats for threatened and near-threatened species, and this has positive effects on many species. By 2015, about 70 000 areas covering a total area of about 750 square kilometres had been identified as key biotopes through environmental inventories. This corresponds to almost 1 % of the total area of productive forest. Since environmental inventories have not yet been carried out for all forest properties, the proportion of productive forest set aside as key biotopes is expected to increase.

The Government’s position is that protecting more forest will have substantial positive effects on a large proportion of the threatened forest species in the areas concerned. Forest protection is intended to safeguard areas that are important for threatened species and to build up networks of protected areas including a representative selection of different forest types, geographical areas and climatic conditions. Thus, establishing nature reserves in forest areas is an effective way of safeguarding a large number of threatened species that require a wide range of different ecological niches and are found in many different geographical areas. There is a need to expand protection of forest areas, see Chapter 7.

Forest habitats that are important for threatened species and should be safeguarded by protection under the Nature Diversity Act include lime-rich broad-leaved forest (oak, beech and lime) and several types of old-growth forest.

The area-based measures discussed above will not adequately safeguard all threatened forest species. Certain species have such small populations that chance events could cause their extinction in Norway. For these, the Government will consider designation as priority species. This is dependent on adequate information about the species in question. Designation as priority species or species protection will also be considered for species that are mainly threatened by direct exploitation (for example that are collected or harvested for sale). Finally, designation as priority species will be considered for some wildlife species that are not particularly closely associated with one specific habitat.

The problems that can arise when cervid populations become too large are mentioned in Chapter 5. There is little to suggest that large cervid populations alone are the reason why any species are threatened. However, the general elements of cervid management described in Chapter 5.5 will reduce any negative impacts of cervids, which may also benefit threatened species.

Management of the threatened forest-dwelling large carnivores (wolf, brown bear and lynx) and the golden eagle is based on the Bern Convention, the Nature Diversity Act and the 2004 and 2011 national cross-party agreements on carnivore management. The 2011 agreement specifies that there must be a clear division into zones where the carnivores are given priority and others where livestock have priority.

The regional carnivore management boards are responsible for drawing up carnivore management plans and updating them regularly. The plans must clearly identify the zones where carnivores have priority and those where livestock have priority. They must also set out proposals for the use of funding on measures to prevent and reduce carnivore-human conflicts in accordance with the dual goals of the management regime. The management plan areas are not based on municipal or county boundaries.

The carnivore and livestock zones in the management plans can be adjusted to separate carnivores and livestock even more clearly, both spatially and temporally. This will create a more predictable situation for livestock farmers and help in achieving the population targets for the large carnivores. With this in mind, the management plans must 1) seek the optimal spatial coordination of carnivore and livestock zones between regions and in cross-border areas, 2) ensure that carnivore breeding zones overlap as far as possible, and 3) take into account carnivore biology, distribution and population connectivity and the availability of suitable habitat. Livestock zones should be delimited so that they are continuous, provide for predictability in carnivore management and make livestock farming viable in practice.

Several habitat types in Norwegian forests are threatened. One of them, calcareous lime forest, is considered to be vulnerable and is already a selected habitat type. Other threatened habitat types include coastal spruce and pine forest (a large proportion of their range is in Norway) and forest types that are spring-fed or on calcareous soils. A number of these habitats are also important for threatened species. The most important pressures vary from one habitat to another, but include forestry, land conversion and mining.

The Government will consider whether to designate more selected habitat types in forest. Since there are a number of pressures on such habitats, and they are regulated under different legislation (including the Forestry Act, the Water Resources Act, the Watercourse Regulation Act, the Energy Act, the Mineral Resources Act and the Planning and Building Act), the Government’s view is that the cross-sectoral approach required for selected habitat types will have a positive effect on these forest habitats. However, designation of selected habitat types does not afford strict protection. For threatened habitats that are only found at a few localities in Norway, such as forest on ultramafic soils and beech and lime forest on lime-rich soils, and for particularly valuable areas of all threatened forest habitat types, the Government will therefore consider protection of areas under the Nature Diversity Act as well as or instead of designation of selected habitat types.

6.4.5 Cultural landscapes

The main threat to most species and habitats in the cultural landscape is the discontinuation of active use (grazing and haymaking), followed by overgrowing of the open landscape. The Government’s main approach to safeguarding threatened species and habitats in the cultural landscape is therefore to provide a framework that encourages grazing on a commercial basis (using schemes that are part of the Agricultural Agreement), in combination with grant schemes to promote habitat management and grazing where there are threatened habitats.

Intensification of agriculture and land-use changes can also have negative impacts on cultural landscapes.

The conversion of agricultural areas for other purposes can result in habitat fragmentation and reduce the connectivity of ecological networks and natural corridors in cultural landscapes. To reduce the negative impacts on threatened species, the Government will promote the use of coordinated regional land-use and transport plans. This will also reduce the pressure for new cultivation of other areas, which may include important habitats. In a few cases, designation of priority species associated with the cultural landscape may also be appropriate, in accordance with the criteria set out in Chapter 6.2.

Three semi-natural habitats – hay meadows, hay fens and coastal heathland – have already been designated as selected habitat types. Hay meadows have been a selected habitat type since 2011, and have shown a positive trend, with an increase in the number of sites that are being actively managed. This is partly because it is possible to apply for grants for habitat management of selected habitat types. The Government will use the experience that has been gained as part of the basis for assessing whether designation of selected habitat types is a suitable measure for other threatened habitats associated with cultural landscapes.

One problem for many of the species associated with hay meadows is that these are isolated habitat islands, often at considerable distances from each other. The Ministry of Climate and Environment will in consultation with other relevant ministries consider which other types of areas, for example species-rich road verges, can function as part of ecological networks.

Invasive alien species are already having a negative impact on several habitats in cultural landscapes, such as sand dunes, open areas on shallow lime-rich soils and semi-natural meadows. The Ministry of Climate and Environment will therefore in consultation with other relevant ministries identify pathways of introduction and particularly vulnerable areas and habitats in cultural landscapes, so that action can be taken specifically to prevent the spread of invasive alien species.

A combination of general measures to promote the maintenance of farming activities and measures specifically to safeguard particularly valuable areas, together with information activities, will have the greatest positive effect on threatened species and habitats in cultural landscapes. The scheme for selected agricultural landscapes is a good example of the second category, and is designed to safeguard a representative selection of valuable Norwegian agricultural landscapes. Under the scheme, multi-year agreements are concluded with landowners, who undertake to manage the land in a way that safeguards both the overall cultural landscape and the threatened species and habitats in the areas. The Government therefore intends to continue the scheme.

There are also some naturally open lowland habitats, and the main threats to these are often physical disturbance and pollution. Open lowland areas are often important elements of the landscape in addition to supporting threatened species, so that establishing protected areas under the Nature Diversity Act can be an important measure. The Government will therefore review open lowland areas where there are threatened habitat types, and consider whether the protection of areas is an appropriate step.

6.4.6 Mountains

Considerable areas of the Norwegian mountains are already protected as national parks or other types of protected areas. Many of the threatened mountain species are found in these areas. Only a small number of developments might be enough to cause the regional extinction of or a serious population decline in these species. More than half of the threatened mountain species (34 of 64 species), and most of the threatened mosses and vascular plants, are found in lime-rich areas. The Government therefore considers it important to map lime-rich areas in the mountains in more detail to develop an overview of any such areas outside the existing protected areas. If there are many lime-rich areas and threatened species that are not adequately safeguarded by the existing protected areas, the Government will consider protection under the Nature Diversity Act for the most important localities and designation as selected habitat types for the rest. Moreover, the Ministry of Climate and Environment and other relevant ministries will provide clear guidance on how to safeguard valuable and threatened mountain species and habitats, and species that need large, continuous areas of habitat, with reference to sectoral legislation and the Planning and Building Act.

Caves have been identified as a threatened habitat type in Norway. The Government proposes designation as a selected habitat type as a way of safeguarding caves that are affected by quarrying, land-use changes, hydropower developments and pollution. However, designation as a selected habitat type does not make it possible to regulate access, tourism and other recreational uses. The Government will therefore consider protection under the Nature Diversity Act and restrictions on access for localities where this is the main pressure. Restrictions on access should be accompanied by a strategy for visitor access to each cave to ensure a good balance between conservation and use.

Management of the threatened large carnivores and golden eagle in the mountains is based on the Bern Convention, the Nature Diversity Act and the 2004 and 2011 national cross-party agreements on carnivore management. Culling of wolverine by licensed hunters is not effective enough at present, and the Government therefore wishes to test some new measures to improve the efficiency of the cull. The Government’s policy for management of large forest carnivores is described in Chapter 6.4.4.

6.4.7 Polar ecosystems

General efforts to maintain good ecological status in polar ecosystems are described in Chapter 5, and will also be the most important way of safeguarding threatened species and habitats in the polar regions. Many of the instruments described in Chapter 5 will also be appropriate for targeted measures to safeguard threatened species and habitats. Climate change is a rapidly growing threat to species and habitats in Svalbard, and in addition there has been an expansion of many types of activities both in and around the archipelago. The Government will adapt the management of Svalbard to these changes.

In Svalbard, the strict regime under the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act and associated regulations, and the extensive protected areas, provide a high level of protection against environmental pressures from local activity. The land areas and territorial waters of Jan Mayen (except for two areas where human activity is permitted) have been designated as a nature reserve. This also helps to protect threatened species and habitats in Svalbard and on Jan Mayen. Measures to safeguard threatened species and habitats will be incorporated into the management plans for the large protected areas in Svalbard in the light of climate and environmental change and changes in human activity. Outside the protected areas, threatened species and habitats will be further safeguarded through targeted application of the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act where necessary to counteract environmental pressures.

The Barents Sea–Lofoten and Norwegian Sea management plans focus on the conservation of threatened species and habitats, including Arctic species and habitats. Both the management plans and sectoral legislation that is important for the protection of threatened marine species and habitats are discussed further in Chapter 6.4.1.

A number of the threatened species in the Arctic are migratory species or have populations that are shared by more than one country. International cooperation is essential for effective conservation of these species and their habitats. The Government will strengthen cooperation under the Bonn Convention and within the framework of the Arctic Council on the management of migratory species and populations that are shared between several countries, focusing particularly on threatened species. Special weight will be given to cooperation on species that are dependent on the Arctic sea ice.

Norway has drawn up a national polar bear action plan which focuses on closer monitoring of the population. The polar bear monitoring programme will be further developed on the basis of the plan. Cooperation between the five polar bear range states – Canada, Greenland/Denmark, the US, Russia and Norway – was strengthened with the adoption of a circumpolar action plan at the meeting of the parties to the Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears in September 2015.

More knowledge needs to be built up about threatened species and habitats in the Norwegian part of the Arctic, and more systematic evaluations need to be carried out. It is particularly important to learn more about the implications of climate change for threatened species and habitats in the Arctic. The Government will further develop the knowledge base for the red lists of threatened species and habitat types in Svalbard, focusing on marine habitats and habitats associated with sea ice.

Since climate change is a significant and growing pressure on species and habitats in the polar regions, the Government’s efforts to combat climate change will be especially important for threatened species and habitats in the Arctic.

6.5 Genetic resources

Biodiversity exists at different levels. Genetic diversity means variety at the level of genes and genetic material, and in genetic make-up between individuals of the same species. This diversity provides the basis for evolutionary adaptation of species to different physical surroundings and climatic conditions. In-situ conservation of genetic diversity is part of the overall effort to safeguard biodiversity. The international framework for this work is set by the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing under the Convention, and the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. In Norway, the Norwegian Environment Agency is responsible for coordinating initiatives for in-situ conservation of genetic diversity.

Aichi target 13 under the Convention on Biological Diversity is about maintaining the genetic diversity of cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and their wild relatives. This genetic diversity includes valuable traits that can improve the adaptive capacity of agriculture to climate change and give greater resistance to diseases.

The agricultural sector has a special responsibility for monitoring, conservation and sustainable use of national genetic resources for food and agriculture. Norway is involved in international cooperation under FAO to achieve Aichi target 13, among other things through the adoption of global plans of action for genetic resources for food and agriculture. The Norwegian Genetic Resource Centre, which is part of the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research, is responsible for implementing and updating Norway’s national action plans for the conservation and sustainable use of genetic resources in farm animals, forest trees and crops, including the wild relatives of food plants.

Ex-situ conservation of genetic resources for food and agriculture takes place primarily in sperm banks, seed banks, clone collections, museums, arboreta and botanical gardens, while in-situ conservation involves the active use of populations of farm animals and crop plants, and the conservation of genetic diversity in natural populations of forest trees. The Government will continue Norwegian participation in Nordic gene bank cooperation through NordGen (the Nordic Genetic Resource Center) under the Nordic Council of Ministers and operation of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault as a repository for duplicates of seed collections from the world’s gene banks. In addition, active cooperation with private- and public-sector actors will be used to maintain stands of forest trees, clone collections, sperm banks and seed banks of genetic resources for food and agriculture.

Conservation strategies for traditional breeds of farm animals, crop varieties and forest trees are based on the principle that genetic resources for food and agriculture are best safeguarded by using them in farming and forestry. Conservation efforts can make it possible to produce specialised products and products with attractive qualities that can provide income for farms and local communities and thus ensure sustainable resource use. Grant schemes for environmental measures in agriculture and forestry provide important support for these efforts. The Agricultural Agreement also includes grant schemes for farm animal breeds of conservation value, and the scheme for native endangered cattle breeds will be expanded to include endangered breeds of sheep, goats and horses that are native to Norway.

In-situ conservation of forest trees and of wild relatives of crop plants can be achieved by safeguarding specific habitats and areas where they grow, for example by sustainable use and habitat management. One advantage of in-situ conservation is that plants can adapt to a changing climate and other changes in environmental conditions. Establishing protected areas and other measures under the Nature Diversity Act can make an important contribution to this work. Other measures may include habitat management for hay meadows and ensuring that the conservation of genetic resources is included in operational management plans drawn up in accordance with section 47 of the Nature Diversity Act. It is important that both environmental and agricultural grant schemes are maintained, among other things to safeguard threatened species and habitats.

The Norwegian Genetic Resource Centre is currently running a project on in-situ conservation of crop wild relatives in protected areas in Norway. The project has identified more than 200 species in the Norwegian flora that are either utility plants themselves or related to important food or feed plants, and that should be maintained in their natural habitats. In this way, their natural genetic diversity and traits that are specially adapted to the climate and growing conditions in Norway can be safeguarded and continue to develop. In-situ conservation is also being used for forest genetic resources, and gene conservation units for forest trees have been established in 23 protected areas (nature reserves). Genetic resources that are important for commercial forestry are maintained both in selected forest stands and in seed orchards. Seeds from important stands of forest trees are kept in NordGen’s seed collection and in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault to provide information on changes in genetic composition over time. Chapters V and VII of the Nature Diversity Act provide the legal framework for this work. The environmental authorities are responsible for following up the Act by developing further legislation and agreements on the collection and use of genetic material obtained from the natural environment.

We currently know too little about how genetic diversity is being affected by factors such as habitat fragmentation and degradation or climate change. The Government therefore considers it important to continue knowledge development, including through national mapping and monitoring programmes, and to develop good conservation strategies, for example using action plans and management plans.