6 Longyearbyen

6.1 Introduction

One of the overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy is maintaining Norwegian communities in the archipelago. This objective is achieved through the family-oriented community life in Longyearbyen.

Longyearbyen is not a cradle-to-grave community, and there are clear limits to the services that should be made available for residents of the community. This is reflected in the archipelago’s low level of taxation and the fact that the Norwegian Immigration Act does not apply here. The Government’s aim is for Longyearbyen to remain a viable local community that is attractive to families and helps to achieve and sustain the overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy.

Continued development within existing activity will contribute to this. It is nonetheless desirable to facilitate growth of a broader and more diversified economy. In connection with the estimated accounts for the 2015 central government budget, NOK 50 million was allocated to measures that will help enable restructuring and rapid employment in Longyearbyen. An important reason for this decision was the challenging situation faced by the coal company Store Norske Spitsbergen Grubekompani (SNSG) and the consequences for Longyearbyen. Many jobs have already been lost as a result of the situation. When downsizing of the company began in 2011, there were approximately 350 employees in the corporate group. A large part of them, however, commuted between Svea and the mainland. For as long as the operating pause continues, there will be about 100 employees in the company, including the activity at Mine 7 and administrative staff. Implementation of the operating pause will be determined one year at a time, but not beyond 2019. It must be assumed that a reduction in revenue on such a scale will have consequences for other activities in Longyearbyen. The circumstances surrounding the SNSK group are described in more detail in Chapter 9, ‘Economic activity’. Of the restructuring package’s NOK 50 million, Innovation Norway was awarded NOK 20 million. The funds are used to maintain Norwegian presence and activity in Longyearbyen, and not least to develop and support commercial projects that are compatible with and support the objectives of the Svalbard policy.

The Longyearbyen Community Council has a key role in the restructuring process, and there is close dialogue between the council and Innovation Norway. It follows from Section 29 of the Svalbard Act that the council’s task is rational and efficient administration of the public interest pursued within the Svalbard policy framework, with the aim of environmentally sound and sustainable local community development. The Longyearbyen Community Council has been awarded NOK 4.5 million of the restructuring package to strengthen its effort to develop the local community further. The Svalbard Chamber of Commerce, with its knowledge of the local conditions and economy, has been awarded NOK 0.5 million. Another NOK 3 million has been allocated to development of a business and innovation strategy directed by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries. In addition, the Longyearbyen Community Council has been awarded NOK 22 million to reduce the maintenance backlog in infrastructure while contributing effectively to construction-sector employment.

The Government emphasises that efforts to restructure Longyearbyen have been going on for a long time. At the start of the 1990s, Longyearbyen was described as a ‘one-industry town’ (see Report No. 50 (1990–1991) to the Storting). Ten years later, during consideration of Report. No. 9 (1999–2000) to the Storting (see Recommendation No. 196 S (1999–2000)), it was determined that many of the conditions that previously had justified calling Longyearbyen a one-industry town had changed. A better range of public services had sprung up, and the community had also gained a broader business base. In addition to the mining operations, there had been a rise in tourism, research and higher education, space-related activity and other enterprises. Although services in some areas, such as healthcare, are limited, Longyearbyen today is seen as a local community with a well-developed public infrastructure, good public services and a broad-based, diverse economy.

The Government wants this trend to continue within the framework of the overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy, so that in future the community will continue to possess the character, breadth and variety that make living in Longyearbyen attractive, thereby supporting the objective of maintaining Norwegian communities in the archipelago.

The Government does not, however, wish to facilitate a form of growth that quickly triggers a need for heavy investment in new infrastructure such as water supply and heat and electric power production. Establishing and maintaining infrastructure in an Arctic climate is costly, and the Longyearbyen Community Council already faces significant challenges maintaining existing infrastructure. Significant investments in recent years have also been made in energy provision to ensure continued stable production of electricity and heat. The sum total of the investments undertaken over many years provides Norway as a whole with an infrastructure at 78° N not found anywhere else at the same latitude.

The central government has long borne a special responsibility for the development of infrastructure in Svalbard. Relevant reference is made to Report No. 22 (2008–2009) to the Storting (see Recommendation No. 336 S (2008–2009)), in which the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs stated: ‘The committee refers in this context to the strong national interests and international legal obligations associated with the archipelago, and to the resulting requirement of strong state involvement. This should apply in particular to upgrading and construction of heavy infrastructure as well as energy supplies and port facilities.’

The Government wishes therefore to emphasise the importance, now and in future, of strong state involvement in the further development of strategic infrastructure in the archipelago.

The introduction and growth of activity at the University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS) exemplify the development of infrastructure that has also contributed significantly to the development of the Longyearbyen community. UNIS has 110 permanent employees (2015), several adjunct professor/adjunct associate professor positions and a number of visiting researchers. The employees and their families in combination with UNIS students constitute about 25 per cent of Longyearbyen’s population. For further discussion of UNIS, see Chapter 8.

A well-functioning infrastructure is essential for value creation, security and an acceptable level of environmental risk. Good infrastructure is also vital to job creation and stimulating economic development. It is therefore important to approach Longyearbyen’s further development in a step-by-step fashion, with ongoing assessment of the effects of the SNSK group’s reorganisation on the community of Longyearbyen and with attention paid to what additional development in various areas would mean for infrastructure capacity.

The avalanche disaster on 19 December 2015 reinforces the importance of such development. The avalanche made more urgent the work of climate-adapted land development and of freeing up space in the centre of Longyearbyen for residential use. Coordinated action will have positive effects for the Longyearbyen community while facilitating desired economic growth. It is of central importance that the plans prepared for economic development be balanced against this land-use planning effort.

Growth of the community beyond today’s level is not an objective. It is important, though, that the character, breadth and diversity of the community make it an attractive place to live, thereby supporting the objective of maintaining Norwegian communities in the archipelago.

Within this framework, there will be a need for some expansion and accommodation of suitable development in selected areas.

6.2 Areas for further development

The central government authorities are responsible for the overarching development framework in the archipelago through such measures as legislation and central government budget allocations. The development work is carried out locally, however. The Longyearbyen Community Council is an important actor in this regard, cooperating, for example, with Innovation Norway and the Svalbard Chamber of Commerce. Coal mining has been a cornerstone in maintaining the Longyearbyen community. It is unlikely that one type of activity alone will be able to offset the loss of jobs in coal mining. It is therefore important to continue investing in existing operations, while also paving the way for new and varied activities. There has long been a deliberate focus on facilitating research and higher education, tourism, space-related activity and various other activities. This has produced good results. Going forward, the Government wants to accommodate further development of activities that can help achieve the objective of maintaining Norwegian communities in the archipelago. This will lay the groundwork in the long run for a more robust community.

6.2.1 Tourism: Longyearbyen and surrounding areas

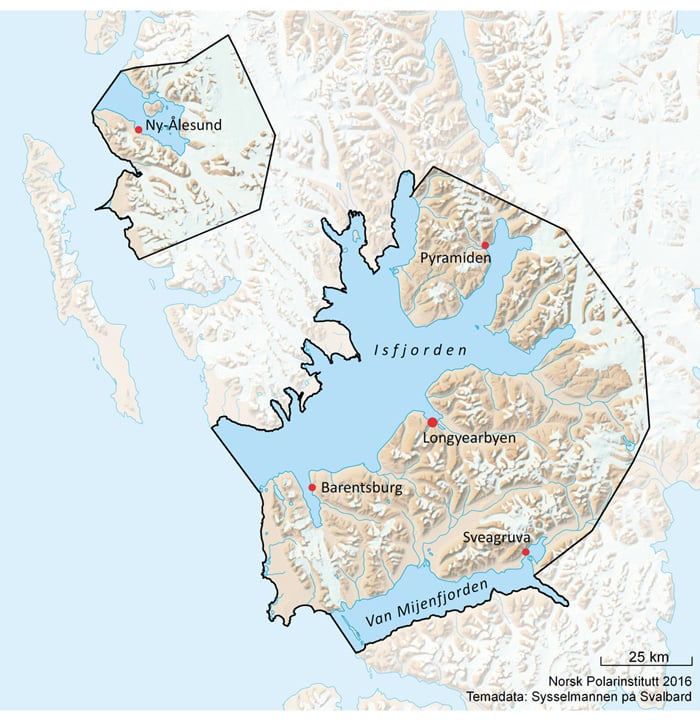

Tourism is one of the principal industries in Svalbard. The tourism industry experienced growth in recent years and is an important contributor to employment in Longyearbyen. Both the city and the areas around it offer significant tourist experience value associated with the unique natural environment and cultural heritage sites located there. With Longyearbyen now undergoing a restructuring process, it is natural that one of the industries being facilitated is tourism. Development of tourism products in Svalbard must include the development of new services and products and of more and better-adapted information. This particularly applies to the areas closest to Longyearbyen, its planning area and the adjoining areas. But it is also important to facilitate environmentally sensitive tourism within the Isfjorden area and Management Area 10, where both Longyearbyen and the other communities are located (see Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Management Area 10.

Map: Norwegian Polar Institute

The development of new tourism products must be sustainable and take place within the limits established by the environmental objectives, safety regulations and other regulations in Svalbard. For the nature-based tourism industry, it is also important to preserve what is unique about Svalbard’s natural environment. Within this framework there is scope for further development of tourism in Longyearbyen. The Government will facilitate the development of tourism in Management Area 10, which includes Isfjorden and the areas surrounding the communities (see Figure 6.1). Local actors in the tourism industry have drawn up a master plan for tourism in Svalbard. It includes elements that could be relevant in future development.

For tourism in Longyearbyen to be able to grow, Longyearbyen must be developed as an arena for visitor experience with a varied range of activity and experiences made available to visitors. Development of attractions in the vicinity of Longyearbyen will provide an important supplement to the existing range of activity, especially during the polar night. An expanded offering of interesting attractions might entice tourists to stay longer than they usually do today. Prolonged stays would result in increased revenue per visitor, which is positive for the business community in Longyearbyen. The ratio of revenue to environmental impact associated with tourist transport to and from the archipelago would also improve. Increased focus on year-round tourism would also be important for the local community in Longyearbyen.

Among the things the tourism industry wants to develop (see the master plan for tourism from 2015) are products related to commercial tourism cabins. In 2007, permission was granted under the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act for the establishment of three commercial cabins for use by the tourism industry in Svalbard. Creating more such cabins may be appropriate as part of the further development of tourism in Svalbard. Such a process would then be based on the same principles and central criteria as the process from 2007, with localisation within Management Area 10 and outside established protected areas, open advertisement of the plan, a limited number of permits and a set of criteria for evaluating projects.

The tourism companies in Svalbard have aired a number of ideas for different types of temporary facilities for overnight or daytime visits in winter within Management Area 10. Such facilities can increase the breadth and scope of tourism products and services. The same can be said of accommodating vessel disembarkation at selected locations in Isfjorden. It is important, in any event, that such facilities be adapted to their surroundings and that comprehensive evaluations of scale, location and environmental impact be undertaken. Tourism companies are in discussion with the Governor about some of these ideas.

Non-motorised tourism packages offering activities such as dogsledding, with Longyearbyen as their base, have undergone significant development, and are now experiencing growing demand. The potential exists for further development and growth of such travel products as dogsledding and skiing trips. Consistent with the objective of limiting motorised traffic in Svalbard, the Government will facilitate this by, for example, exploring opportunities for increased use of the large snowmobile-free area.

The Government will also secure natural places of interest and cultural heritage sites in the immediate vicinity of Longyearbyen that are important for tourism and the local inhabitants. A project will accordingly be initiated to assess the need for greater protection of areas in the lower Adventdalen that are especially rich in bird life. At the same time, simple adaptations will be considered in nearby areas in the form of sherpa trails and similar measures to make nature and cultural sites in the areas more accessible. By making use of the leeway provided by existing regulations and objectives, the Government will ensure sound and predictable framework conditions for tourism in Longyearbyen.

There is also a need for more long-term plans for the use of Management Area 10. Management plans for this area, including both protected and unprotected areas, will therefore be prepared. The Governor has been asked to initiate this work. The purpose is to facilitate and manage use of the area so that the objectives of increased local value creation and positive visitor experiences are fulfilled, even as appreciation for Svalbard’s unique environmental qualities is increased and cultural heritage assets are maintained.

Food culture, too, can be of interest in travel product development. Several actors in Svalbard want to be able to provide local food to their customers, such as meat from Svalbard reindeer and fish from Isfjorden. Such measures contribute both to improving the tourism product and reducing the environmental impact associated with the transport of food. All harvesting in any case must take place within the framework of environmental regulations. Beer brewing and local production of chocolate demonstrate that there is demand for products with a local connection.

For further discussion see Chapter 7, ‘Environmental protection’, and Chapter 9, ‘Economic activity’.

6.2.2 Relocation of public-sector jobs

The Government is considering the possibility of relocating public-sector jobs to Longyearbyen as a contribution to attaining the objective of maintaining Norwegian communities in the archipelago. As a start, the Norwegian Consumer Council is considering establishing three to five office positions in Longyearbyen as part of the agency’s reorganisation. The office will answer directly to the council’s Tromsø office.

At an extraordinary meeting on 19 February 2016 the Ministry of Health and Care Services gave Norsk Helsenett SF (Norwegian Health Network) the task of planning for the creation of a central service centre providing administrative services to the central health and care services administration as part of its activity. The service centre will be responsible for key functions related to procurement, ICT and records/document management. Norsk Helsenett SF’s assignment involves creating a time schedule and work plan to establish the service centre by 1 June 2016 at the latest.

The assignment calls for the service centre to be established in the Oslo area, with redistribution of certain services at a later date to the state-owned enterprise’s other locations in Trondheim and Tromsø, or to Svalbard.

Textbox 6.1 Fredheim: The trapping station that was relocated

Figure 6.2 Fredheim.

Photo: Helene Mokkelbost, Office of the Governor of Svalbard

Fredheim in Sassenfjorden was the trapping station of the renowned trapper Hilmar Nøis. He spent 38 seasons in Svalbard, 35 of them as a wintering trapper. Fredheim was his main station, and where he wintered most often.

The trapping station consists of the main house, Villa Fredheim (begun in 1924 and completed in 1927), Gammelhytta (built by Fredrik Antonsen and Simon Ingebrigtsen in 1908), and an outbuilding constructed at the same time as the villa and used as an emergency cabin. Fredheim is a popular destination for residents and visitors alike in snowmobile season.

For many years shore erosion had crept towards the trapping station. Had nothing been done, the buildings would have been swallowed by the sea. Various measures were considered, including erosion prevention and moving of the buildings. Gammelhytta was moved six metres from the shore’s edge in 2001, but was still not safe.

Actual planning for moving Fredheim started in autumn 2013. Relocation of the station was cleared by the Directorate for Cultural Heritage and the Norwegian Environment Agency, and the project began in earnest in spring 2014.

In the summer of 2014 the buildings were jacked up on steel beams and braced internally, while the floors were removed to avoid damage during the moving process. In April 2015 all the buildings were hauled by tracked vehicle across snow-covered terrain up onto the brink east of the station, and in the summer of 2015 Fredheim were reassembled internally and externally. All work was performed according to antiquarian guidelines.

The relocation itself went smoothly, without damage to the buildings, thanks to good planning and execution. The building group looks much as it did before, and there are no scars in the terrain.

The Governor, as the responsible authority, must preserve a representative assortment of cultural heritage sites as a reference base and source of experience for future generations. Svalbard’s harsh climate is a constant threat to buildings and equipment. Climate change may intensify this threat. Conscious prioritisation is needed to ensure breadth and representativeness for the future.

The Fredheim trapping station is one of the most distinctive and valuable artefacts of cultural history in Svalbard. That is why it was so important to keep the buildings from being destroyed by shore erosion. The project cost about NOK 2 million and was funded by the Governor and the Ministry of Climate and Environment.

6.2.3 Port development

Maritime traffic around Svalbard at present consists largely of cruise and cargo traffic, research-related shipping and some traffic tied to fisheries activity. The trend in recent years has been of generally increasing traffic. Longyearbyen today has three quays: Gamlekaia (the Old Quay), Kullkaia (the Coal Quay) and Bykaia (the Town Quay). In addition, Turistkaia (the Tourist Quay) has been installed as a floating dock of plastic material. Bykaia and Turistkaia constitute Longyearbyen’s public port service, and are the port facilities for heavy cargo and passenger/cruise traffic.

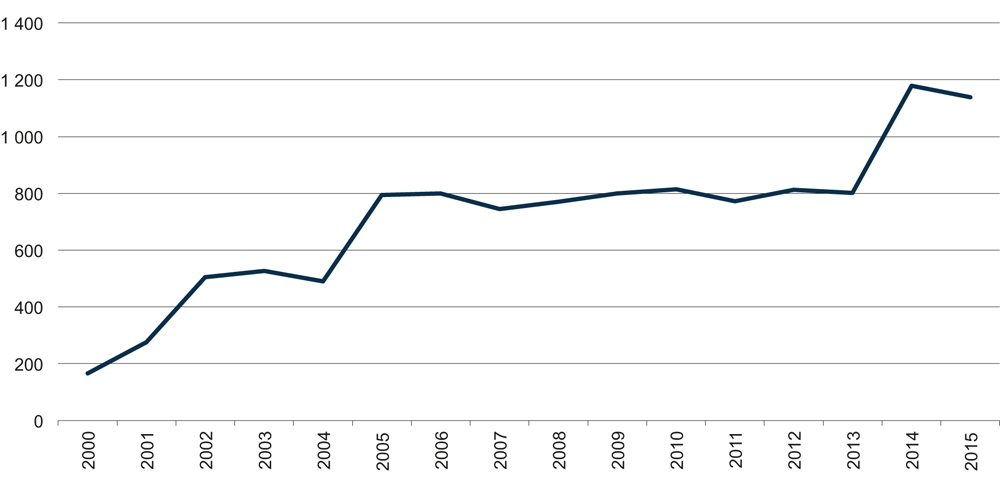

Today there is limited capacity at the port facilities in Longyearbyen, despite relatively heavy traffic to be accommodated in a short season. The capacity limit at Bykaia, which serves the larger tourist and cargo vessels, was reached already in 2005. The number of ships that had to lie at anchor in the 2012–2015 seasons varied between 134 and 179. The total number of port calls in that period ranged from 812 to 1,163. This results in clear limits to whether and how long each cruise ship may dock, and by extension, the degree to which the local economy can take advantage of the cruise traffic.

Longyearbyen’s port infrastructure was discussed in Report No. 22 (2008–2009) to the Storting Svalbard, where it was pointed out that Longyearbyen, because of increased commercial and industrial activity in the Arctic, should expect to gain in importance as a base for rescue and pollution-control preparedness and for maritime services. Since 2009, the need for expanded port capacity has grown. The trend in recent years shows increasing maritime traffic to the Arctic, both in number and in scale, especially for cruise traffic.

Figure 6.3 Increase in the number of Longyearbyen port calls since 2000.

Source Longyearbyen Community Council. The figure for 2015 is for the period up to 15 November 2015.

A number of studies have been conducted locally to identify and document challenges and opportunities for additional port development in Longyearbyen. As a result, the Longyearbyen Community Council has drafted proposals for new port infrastructure that have been submitted to the Ministry of Transport and Communications.

In the current National Transport Plan (NTP) (see Meld. St. 26 (2012–2013) National Transport Plan 2014–2023), up to NOK 200 million in state funds have been set aside in the plan period for upgrading and new construction of port infrastructure in Longyearbyen, based on a cost estimate of NOK 400 million. It is further assumed local actors and private business may contribute to the projects’ realisation. In the 2016 central government budget, NOK 15 million has been set aside for planning of new port infrastructure in Longyearbyen. The Norwegian Coastal Administration (NCA) has been tasked with assessing concepts proposed by the Longyearbyen Community Council for upgrading port infrastructure. The NCA’s report is scheduled to be available in October 2016.

The aim of the NCA’s work is to study the type of port infrastructure necessary to accommodate Longyearbyen’s projected maritime traffic, thus contributing to further developing of the local economy. On the basis of the proposals submitted by the NCA, the Government will determine how to proceed in developing port infrastructure in Longyearbyen.

Figure 6.4 Cruise ship in Longyearbyen’s port.

Photo: Ståle Nylund, Office of the Governor of Svalbard

6.2.4 Svalbard Science Centre

The Svalbard Science Centre opened in 2005 and is the main arena for education and research in Longyearbyen. The University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS) is located at the centre. In addition to UNIS, the centre hosts the Norwegian Polar Institute, the Svalbard Science Forum (Research Council of Norway), the Svalbard Museum and the national cultural history magazine, as well as the University of Tromsø, Akvaplan-niva, the Nansen Environmental and Remote Sensing Center, the Institute of Marine Research, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, SINTEF, the Japan National Institute for Polar Research and the student welfare association. See discussion of the key actors in Chapter 8, ‘Knowledge, research and higher education’. Research in Svalbard is important to the advancement of understanding in many subjects, and has helped expand frontiers in several scientific disciplines. UNIS has received support from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to establish a new Arctic Safety Centre in Longyearbyen. The Arctic Safety Centre is a collaboration between the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, SINTEF, the Norwegian Polar Institute, the Governor of Svalbard, Pole Position Logistics, SvalSat, the Longyearbyen Community Council, Lufttransport and Visit Svalbard.

The establishment, and subsequent expansion, of the Svalbard Science Centre has contributed to a significant amount of activity with positive repercussions in Longyearbyen. It draws not only students and employees, but also tourists and local residents who are increasingly using what it has to offer, including popular science lectures and the Svalbard Museum. A 2014 evaluation1 of the Svalbard Science Centre shows that it is also widely used for entertaining and important visits, and concludes that the centre has contributed to a more diverse economy.

The unique natural environment and geographic location, the long polar traditions and the good access to modern infrastructure make Svalbard an attractive platform for both Norwegian and international Arctic research. This is an area in which Norway has an outstanding opportunity to contribute to the development of global knowledge. There is a strong interest in research, and active publication, dissemination and information are vital if this knowledge is to be shared and used. Presentation of research to a broad audience will contribute to this; likewise, conveying what is unique about scientific research and knowledge production in Svalbard could provide support to other activities, such as tourism.

6.2.5 Land development in Longyearbyen

The Longyearbyen Community Council is working on new land-use plan for Longyearbyen. This work will provide the framework for future development in Longyearbyen. As part of the process the Longyearbyen Community Council is considering moving industry-related operations from the port area known as Sjøområdet to Hotellneset, a nearby peninsula, creating at the same time a ‘greener’ Longyearbyen. This will free up space in more central areas of Longyearbyen for other potential use, such as housing. It is also the Longyearbyen Community Council’s wish to develop Hotellneset into a future business park and to accommodate new economic activity there. A prerequisite for developing the area is facilitation of infrastructure, such as electricity and water supply. There is uncertainty as to the extent of pollution in the ground and the clean-up costs. According to the Longyearbyen Community Council, potential development of Hotellneset will also require construction of a warehouse to store coal.

Efforts to free up space in the centre of Longyearbyen have been further highlighted by the avalanche disaster in December 2015. A number of houses were destroyed and cannot be rebuilt in the area they occupied before the avalanche. This has created a new situation which, in the view of the Longyearbyen Community Council, requires rapid creation of new residential areas that will mean reallocating other land. The Government therefore proposes to increase the allocation by NOK 10 million for residential construction and land development in Longyearbyen. Reallocation undertaken in coordinated fashion should produce positive effects for the Longyearbyen community while facilitating the desired economic development. The council is therefore considering undertaking a speedy examination of land use in Longyearbyen and initiating the work of laying out new infrastructure.

6.2.6 Energy supply

Supplying energy, both heat and electricity, is one of the Longyearbyen Community Council’s most important tasks, and also one of the most costly. The Longyearbyen power plant is a coal-fired cogeneration station dating from 1983 that supplies electricity and district heating for the whole of Longyearbyen. The power plant is owned by the Longyearbyen Community Council. To stabilise operations and extend the power plant’s life cycle, a large-scale project of maintenance and upgrades has been initiated. The state is covering about two-thirds of the costs of this work.

The overall energy load of the community is large. The power plant currently supplies both electricity and district heating at near its maximum capacity. Demand growth in Longyearbyen could trigger a need for substantial investments in energy production. Establishment and maintenance of infrastructure in an Arctic climate is costly, and the Longyearbyen Community Council already faces challenges in maintaining existing infrastructure. The Government therefore does not want to encourage growth that would quickly trigger a need for major investment in infrastructure such as water supply, heating and power generation systems. It is therefore important that work continue on maintaining existing infrastructure and energy efficiency.

The upgrading of the power plant, which started in 2013, is expected to extend the plant’s life cycle by 20–25 years from the start of the upgrade. In the 2012–2014 period, funds were also allocated for the construction of equipment to scrub the plant’s emissions of pollutants such as sulphur and particulates. CO2 emissions at the Longyearbyen coal plant are high in comparison to the amount of energy produced. Over time, UNIS has developed expertise on CO2 storage possibilities in Adventdalen. The aim of the project has been to investigate whether it is possible to store CO2 in Adventdalen. The project has also aimed to facilitate CO2 research and methodology development. The calculations and simulations conducted so far indicate provisionally that it is probably possible to store CO2 in Adventdalen without CO2 leakage occurring, but that further testing is necessary to be certain. The project has concluded for the time being.

6.2.7 Water supply

Isdammen, a reservoir, is Longyearbyen’s only source of drinking water. The Longyearbyen Community Council is responsible for its operation and maintenance as well as for risks associated with any dam breach and/or water loss. Issues related to sedimentation and leakage are among the significant challenges at Isdammen. The Longyearbyen Community Council has initiated work to secure this drinking water source for the years to come. Isdammen is also the only water source from the beginning of September to the beginning of July each year. The council wants eventually to establish a reserve water source or other solution so water can be supplied if something unforeseen should happen to the primary water source. The council will have the issue examined in the spring of 2016, with engineering and planning of a future reserve source to follow.

Textbox 6.2 Seed vault

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is an underground facility for long-term and back-up preservation of duplicate seeds from the world’s seed collections. The seed vault, established in 2008, is owned by the Norwegian state and administered by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food. The Norwegian Directorate of Public Construction and Property, or Statsbygg, operates the facility, while the Nordic Genetic Resource Centre (NordGen) coordinates the admission of seeds. The seed vault is the largest of its kind, storing more than 870,000 seed samples from the world’s most important crops in 2015. That year, more than 40 per cent of agricultural plant genes were secured here, and new seed samples continue to be added three to four times each year. The aim of Norwegian ownership is to create predictable and secure conditions for the preservation of as much genetic diversity as possible in crops that are important to food and agriculture, and thereby to improve global food security. The seed vault generates considerable international interest, and has raised awareness about the importance of protecting genetic material, as well as about Svalbard and Norway, in part due to media coverage around the world. For the Norwegian Government, it is important to maintain a long-term perspective in preserving the seed collections in the vault.

6.3 Provision of services

6.3.1 In general

In the previous white paper (Report No. 22 (2008–2009) to the Storting Svalbard) it was stated that Longyearbyen should continue to be developed as a qualitatively good community with welfare and other services tailored to the community’s size and structure, all within an environmentally acceptable framework. ‘Robust family community’ is the phrase often used. It was also determined that Longyearbyen was not to become a cradle-to-grave community with fully developed service offerings, and that such a policy was both a prerequisite for the low tax rate and a consequence of there being no requirement in Svalbard for foreign nationals to hold work or residence permits. The Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs said in its consideration of the Svalbard white paper (Recommendation No. 336 S (2008–2009) that «(...) these factors mean that the community frameworks must necessarily be somewhat different than for local communities on the mainland, and the committee believes this is an appropriate form of organisation». Longyearbyen today is seen as a local community with well-developed infrastructure and good services. The ‘normalisation’ that has guided community development here in recent years has, in the Government’s view, been successful, and Longyearbyen currently exhibits the characteristics of a ‘robust family community’, with services tailored to its needs. There is no intention to develop services beyond the current level.

Services in Longyearbyen are seen to by both central and local actors. Basic services are provided by the Longyearbyen Community Council, Longyearbyen Hospital, the Governor of Svalbard and several other actors. The Longyearbyen Community Council also provides all infrastructure services inside the Longyearbyen land-use planning area. It is also responsible for the school, the kindergartens and the child and family service. A number of other services and facilities, including a library, a sports and swimming hall, a cultural centre and a youth club, are also provided by the community council.

Additional services in Longyearbyen are supplied by others, including both public and private agencies. Examples include infrastructure-related services, such as the airport and data and telecommunications, and service functions such as banking and postal services. Longyearbyen also has a varied assortment of shops, dining and overnight accommodation, restaurants and other entertainment spots.

The Government will continue to facilitate a low taxation level in Svalbard. In conjunction with other framework conditions, this gives an indication of the intended service level in Longyearbyen, and of its continued limitation with comparison to the mainland. For the foreseeable future, therefore, Longyearbyen will not become a cradle-to-grave community.

Figure 6.5 Camp Svalbard offers outdoor camp weekends, summer and winter, for youth aged 13 to 18 who are residents of Svalbard. Participants experience Svalbard’s natural landscape in safety, with competent instructors and leaders.

Photo: Marianne Stokkereit Aasen/Longyearbyen Community Council

6.3.2 Cultural activity

Culture and sports are strong focal points in Longyearbyen. Although institutionalised cultural offerings are naturally limited, the cultural life is extensive, with wide-ranging and diverse options. These include both professional organisations and voluntary activity in most parts of the cultural field.

The Longyearbyen Cultural Centre contains both cinema and stage. Galleri Svalbard presents permanent and temporary art exhibitions. The gallery also offers a residence for visiting artists. Longyearbyen has a public library, and the Svalbard Museum displays exhibits from Svalbard’s culture and history to the present day. The Northern Norway Art Museum has established Kunsthall Svalbard at the Svalbard Museum, for temporary contemporary art exhibitions. The Northern Norway Art Museum is also considering the possibility of establishing an artist residence/guest studio in order to accommodate artists who wish to work there.

The cultural arts school offers children and young people fully qualified instruction in a variety of cultural subjects. There is a broad spectrum of clubs and associations, including several sports teams. Sporting facilities include a multi-purpose hall and a swimming hall.

It is important that residents in Svalbard have access to a wide variety of high-quality cultural activity, much as the rest of the country does. This is consistent with the premise of Norwegian cultural policy: that culture has both intrinsic value and value to individual residents. Climate and surroundings may restrict the opportunity of people in Svalbard, compared with people elsewhere in Norway, to develop and express themselves. In this perspective, a well-functioning cultural scene contributes to quality of life and a desire to live in Svalbard. A broad and diverse cultural life also has an affect on other aspects of society.

Cultural affairs can provide important support to the tourism industry, both in terms of cultural expertise and the cultural content in tourism products. Surveys show that tourists increasingly seek out cultural experiences when travelling, and that those who do so represent an affluent customer group. Cultural initiatives could represent an important element in further efforts to develop the Svalbard community; see section 9.4.1, ‘The tourism industry’.

Svalbard Church is located in Longyearbyen, and is part of the Church of Norway. The church is open to all, and is also a resource for the other Svalbard communities. The church is an important culture-bearing institution in the local community, and a cultural actor as well. The church serves a unifying function, especially when accidents or disasters strike, and it plays a central role in emergency preparedness. It is important that Svalbard Church be maintained as part of the cultural and social foundation of the community in Longyearbyen and the other inhabitated locations in Svalbard.

6.3.3 Health and welfare services

The Northern Norway Regional Health Authority, through the University Hospital of North Norway (UNN Tromsø), is responsible for public health services in Svalbard. The University Hospital of North Norway-Longyearbyen Hospital (UNN Longyearbyen) provides essential health services. The healthcare service in the archipelago is organised differently from the system in the Norwegian mainland, where municipalities are required to ensure that an array of local health and care services is provided. The Longyearbyen Community Council does not have such a responsibility. Longyearbyen Hospital provides some types of service not normally provided in hospitals; see below. Longyearbyen is not a community with services available for all phases of life, so care services and other services of a prolonged nature, such as home nursing care, nursing home stays, respite care, practical assistance, etc. People who need such services must therefore receive them in their home municipalities on the mainland. Foreign nationals without any connection to the mainland will have no such opportunity, and must therefore obtain such services in their own countries. For further discussion of this issue, see section 5.3.1.

Longyearbyen Hospital has six beds for admission and observation. The hospital is prepared for emergency response 24 hours a day. This includes outpatient clinic examinations in cases of suspected illness or injury. Medical treatment and minor surgical procedures can usually be performed at the outpatient clinic, while patients who need to undergo further testing or to be referred to a specialist other than one that Longyearbyen Hospital can offer must seek help on the mainland or in their home country. Emergency medical services are provided to people travelling in the archipelago and adjacent waters, without their being resident in Svalbard. In Barentsburg, the mining company Trust Arktikugol has a healthcare service in connection with its operations, but Longyearbyen Hospital helps when needed.

Emergency medical services in Svalbard consist of an emergency medical dispatch centre (AMK), an emergency assistance service, an ambulance service, off-road rescue in cooperation with volunteers, a rescue helicopter service organised by and in cooperation with the Office of the Governor, and an air ambulance service to the mainland. Longyearbyen Hospital is part of the University Hospital of North Norway (UNN Tromsø) and cooperates with UNN Tromsø, sometimes via video-based medical emergency interaction (VEMI). This enables medical consultation and guidance from UNN Tromsø to employees at Longyearbyen Hospital.

Longyearbyen Hospital provides some types of service not normally provided in hospital, including services comparable to primary healthcare on the mainland, such as general practice medicine, midwifery, health visitor services and physiotherapy. The hospital also has a dental service and an occupational health service, but no permanent psychologist service.

Treatment costs and deductibles for health services rendered at Longyearbyen Hospital are covered largely in accordance with rules and rates applicable on the mainland. In cases where the patient is neither a member of Norway’s National Insurance Scheme while in Svalbard nor covered by a mutual agreement Norway has concluded with another country, and which includes Svalbard, the patient must either have insurance that covers the expenses or pay directly for the treatment. The EU regulation on the coordination of social security systems (Regulation 883/2004), whose area of application includes medical assistance in the European Economic Area, does not apply to Svalbard.

Veterinary service

There are animals in Svalbard, too, and dog keeping is widespread, especially in the tourism industry. On the mainland, animal health and welfare are safeguarded through special legislation, including the Food Act and laws governing animal welfare and animal health personnel. The Ministry of Agriculture and Food is the competent ministry for this legislation. The Food Act and the Animal Welfare Act are applicable in Svalbard. The Act relating to veterinarians and other animal health personnel, however, does not apply to the archipelago. On the mainland, municipalities are responsible for ensuring satisfactory access to veterinary services, which are performed by private-practicing veterinarians. Municipalities are also responsible for organising on-call clinical veterinary services. In 2013 a private veterinary practice was established in Svalbard. It has received annual subsidies from the Ministry of Agriculture and Food. The Ministry of Justice and Public Security has also contributed start-up support.

On the mainland, no veterinarians in private practice receive support from the Ministry of Agriculture and Food. Certain municipalities where economic activity is sparse and access to veterinarians is unstable are provided government grants for measures to secure adequate supply of veterinary services. As mentioned, the Act relating to animal health personnel is not applied in Svalbard. Nor is Svalbard a municipality in its own right, which means mainland systems and programmes related to this topic are not automatically transferrable. The possibility of making the Act relating to animal health personnel applicable in Svalbard will be considered in connection with an upcoming revision of the act.

6.3.4 Children and youth

The number of children and young people in Longyearbyen has grown in step with the development as a family community. While in 2008 there were 372 people aged 0–19 in Longyearbyen, the number in the 2015–2016 school year was 430.

There are two kindergartens operating in Longyearbyen. Both are run by the Longyearbyen Community Council, with all-day care available for children aged 0–6. The coverage rate in Longyearbyen is currently 100 per cent, and places are made available within three months of application. After several years of a growing child population and expansion in day-care capacity, the number of children in day-care has now declined from 145 children in 2012 to 107 in 2015, and the operating level has been adjusted accordingly. During the same period, the proportion of foreign children in the kindergartens has risen from 20 per cent in 2013 to 32 per cent in 2015.

The Longyearbyen Community Council is also responsible for schooling in Longyearbyen. Longyearbyen School has a primary and lower secondary school as well as a department for upper secondary education; after-school and cultural arts programmes are also available. The Governor of Troms county supervises the school, while the Governor of Svalbard assists on issues relating to matters in Svalbard. In the 2015–2016 school year, there are 225 primary and lower secondary school pupils and 25 pupils receiving upper secondary instruction. Ten per cent of the pupils are from outside Norway.

As mentioned in section 5.3.5, the Education Act and the Kindergarten Act determine the framework for the Longyearbyen Community Council’s duties in providing for education. According to the regulations, education at the primary and lower secondary level must be provided, while the council may choose to provide upper secondary instruction. The Education Act also contains provisions on individual adaptation for pupils with special needs.

The regulations pertaining to schools and kindergartens in Longyearbyen are described in more detail in section 5.3.5. Due to the operative principle of applying them «to the appropriate degree» or «circumstances permitting», a need has arisen to clarify the scope of the council’s duties in a number of areas. With regard, for example, to the duty to provide special education for pupils in the upper secondary level, the Ministry of Education and Research has ruled that the Longyearbyen Community Council is not obliged to provide such instruction. The ministry has nevertheless urged the council to do as much as possible to adapt its upper secondary instruction, to the degree local conditions permit, for the benefit of pupils with special needs.

Report No. 22 (2008–2009) to the Storting Svalbard indicated furthermore that the Longyearbyen Community Council itself must consider which special services to provide beyond what is necessary under statute, but to do so «on the basis of an overall evaluation», taking into account the resources that such services require and proportionality with regard to the rest of the services provided.

Figure 6.6 Every year on 8 March, the return of the sun is marked with a traditional gathering on the old hospital steps at Skjæringa.

Photo: Anastasia Gorter, Office of the Governor of Svalbard

This presents the Longyearbyen Community Council with challenges and hard choices involving both its direct obligations and any additional services it is to provide, in which case different needs must be weighted and prioritised. The fact that many pupils are foreign nationals raises special issues. The council has therefore asked for guidelines on how the regulations should be practiced, and which services are to be provided.

The Government wishes to emphasise that the low taxation level and the fact that immigration legislation does not apply to Svalbard make for special framework conditions in the local community of Longyearbyen. Longyearbyen is not intended to be a cradle-to-grave society, and the aforementioned framework conditions are dimensioned for the services that are to be provided, and by extension for the expectations residents should have regarding, for example, special services for children and youth. The Government therefore believes that the adapted school services and the restrictive practice currently in place should be continued, and that providing services beyond the current level is not an objective. Nor, accordingly, should the Longyearbyen Community Council provide services of a clear social-policy character.

Further work will therefore be done, as also mentioned in section 5.3.5, to clarify the council’s obligations with respect to the Kindergarten Act, the Education Act and the proposed act on gender equality and prohibiting discrimination. This work will also include clarifications needed as a result of structural and quality-based child welfare reforms, and changes in the division of responsibility between the state and the municipalities.

Table 6.1 Population in Longyearbyen, by nationality.

Country | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015* | 2016** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Norway | 1652 | 1604 | 1637 | 1643 | 1569 | 1557 | 1513 | 1472 |

Thailand | 93 | 92 | 103 | 103 | 112 | 111 | 116 | 116 |

Sweden | 65 | 72 | 91 | 94 | 107 | 125 | 123 | 141 |

Denmark | 32 | 27 | 31 | 37 | 30 | 41 | 43 | 40 |

Germany | 26 | 23 | 23 | 25 | 25 | 30 | 38 | 39 |

Russia | 30 | 35 | 39 | 42 | 42 | 47 | 47 | 50 |

Ukraine | 8 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 16 | 23 | 26 | 21 |

Philippines | 10 | 12 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 27 | 37 | 40 |

Other, Europe | 51 | 57 | 64 | 80 | 87 | 117 | 133 | 144 |

Other, outside Europe | 27 | 32 | 54 | 52 | 48 | 54 | 68 | 67 |

Total | 1994 | 1963 | 2068 | 2107 | 2056 | 2132 | 2144 | 2130 |

* as of 1 December 2015

** as of 1 April 2016

Source Svalbard Tax Office

6.3.5 Foreign nationals

Opportunities for gainful employment and a reasonably well-developed list of services, along with the fact that work and residence permits are not required in Svalbard, have made it attractive for foreign nationals to settle in Longyearbyen. The population structure is therefore changing. The number of foreign nationals has increased from 326 in 2008 to 658 as of 1 April 2016; it has in other words almost doubled. The number of Norwegian nationals, however, has decreased in the same period, from 1,692 to 1,478. While foreign nationals accounted for 15 per cent of the population in 2008, the proportion on 1 April 2016 was about 31 per cent. In primary and lower secondary school, about 10 per cent of the children are foreign nationals, while in the kindergartens the figure is about 32 per cent. In one of the kindergartens, 37.5 per cent of children are foreign nationals, from 11 different countries.

This population trend raises several issues that relate in particular to the situation of children and youth. While the services provided in Longyearbyen are available to all residents, including foreign nationals, it is indeed limited, and does not address all needs, certainly not across the entire human life span. Even a prolonged stay in Longyearbyen will not by itself open the way to a further stretch of time on the mainland for foreign nationals; see discussion in section 5.3.3. This is also the case for foreign children born during their parents’ stay in Svalbard. Norwegian nationals may travel to the mainland for further schooling and studies, and to their respective mainland municipalities to fulfil any care needs. Foreign nationals without such ties have no such opportunity, apart from a limited access to upper secondary education. They must therefore return to their home country to fulfil their needs. This may become a challenge, especially for second-generation and, eventually, third-generation children born during their parents’ stay in Longyearbyen, and when ties to the home country over time may have become weak.

Responsibility in such situations rests with the parents. Just as the Norwegian authorities do not wish to facilitate life-long residence for Norwegians in Svalbard, it is not up to the Norwegian authorities to facilitate life-long residence for foreign nationals who choose to stay in Svalbard. It is therefore important that foreign nationals who come to Longyearbyen be given clear, accurate information about the applicable legal and practical constraints of life there, including the limited range of services and the fact that a life-long stay in Longyearbyen cannot be pursued. It will also be important to advise foreign nationals that they have no access to welfare benefits on the Norwegian mainland, and that they will therefore need to maintain contact with their home country. On the mainland, municipalities are responsible for various introduction programmes for foreign nationals. Although these programmes are inapplicable to Svalbard, it is natural for the Longyearbyen Community Council to have primary responsibility for providing such information, in close cooperation with other authorities, such as the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration and the Governor of Svalbard.

When it comes to services specifically geared to foreign nationals, the Longyearbyen Community Council has, as mentioned, no obligation to offer introduction programmes, etc. Although the council offers Norwegian-language instruction for newly arrived foreign nationals, the Government does not intend to make provision for, or fund, additional introduction programmes or other accommodations specifically for foreign nationals in Longyearbyen.

The Longyearbyen Community Council has also pointed out that in certain areas it will be necessary to clarify whether it is obliged to fund services for foreign children; this concern will be followed up in dialogue with the relevant ministries.

6.4 Summary

The Government will:

Seek to maintain Longyearbyen as a viable local community that attracts families and helps fulfil and support the overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy.

Further develop the Longyearbyen community, with various types of development under continual assessment.

Facilitate continued development of existing activities such as tourism, research and higher education, as well as a broad and varied range of economic activities.

Facilitate the possibility of maintaining some activity at Svea during a restructuring period for Longyearbyen, while mining operations at Svea and Lunckefjell are suspended.

Strengthen the Longyearbyen community by increasing funding for housing and land development in Longyearbyen by NOK 10 million.

Facilitate employment and restructuring in Longyearbyen, using funds provided in the estimated accounts for the 2015 central government budget.

Continue efforts to facilitate development of sound infrastructure in Svalbard, including energy and water supply.

Decide on further work to develop port infrastructure in Longyearbyen once the Norwegian Coastal Administration’s conceptual study is completed.

In close consultation with tourism operators, take coordinated action to better facilitate tourism in Management Area 10, which includes the Isfjorden area and areas surrounding the inhabitated locations.

Consider facilitating closer contact between the Governor of Svalbard and the local tourism industry by redirecting resources for this purpose.

Enable the Northern Norway Art Museum to consider establishing a residence/guest studio for visiting artists.

Consider relocating public sector jobs to Svalbard to help achieve the objective of maintaining Norwegian communities in the archipelago.

Footnotes

‘Svalbard forskningspark: Etterevaluering, desember 2014’ (Svalbard Science Centre: Ex-post evaluation, December 2014). Erik Whist, Gro Holst Volden, Knut Samset, Morten Welde and Inger Lise Tyholt Grindvoll (NTNU 2014).