4 Climate change

Global climate change and the loss of biological diversity are two of the greatest threats humanity has faced. Climate change reduces human security as a result of drought, flooding, storms, disease, food and water shortages, and inadequate political capacity to deal with these impacts. The rapid changes we are now seeing could lead to ecosystem collapse.

Climate change may also lead to greater disparity between social groups, between regions and between countries. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), it will probably not be possible to limit global warming to no more than 2 °C above the pre-industrial level unless world greenhouse gas emissions are cut by 50–85 per cent from the 1990 level by 2050. It has been calculated that to achieve this, global emissions must begin to decline within the next ten years. However, even global warming of 2 °C will result in major changes, which now seem to be inevitable.

Figure 4.1 Climate change increases the frequency of extreme weather events.

Source Photo: Abdir Abdullah/Scanpix

Global climate and environmental problems affect everyone, but it is poor people in countries that are most vulnerable to change who will be hardest hit by climate change. Unless we address climate and environmental problems, the results of many years of development efforts will be under threat.

Norway’s development policy will focus on reducing the vulnerability of the poorest countries to climate change, and will encourage countries to draw up forward-looking development strategies that are robust to climate change. The top priorities for most developing countries for many years to come will be economic growth and poverty reduction. In its international cooperation, Norway will seek to assist developing countries to recognise and make use of the potential that lies in following a more environmentally sound path of development than Western countries have done. Environmentally sound, sustainable economic growth and investment will be the most important instruments. The Government will strive to ensure that its climate policy and development policy reinforce one another. This means that climate policy must contribute to the achievement of development policy goals, and that development policy must increase capacity to achieve climate policy goals. The alternative to an integrated policy to combat poverty and climate change is failure on both fronts.

4.1 Ecosystems under pressure

More than 30 years after the first major UN conference on the environment in Stockholm in 1972 warned against continuing to impoverish the world’s ecosystems, and 15 years after the adoption of the Convention on Biological Diversity, the 2005 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment documented that the Earth’s ecosystems are in serious danger. Climate change is having serious impacts on top of the great pressure people are already putting on the environment.

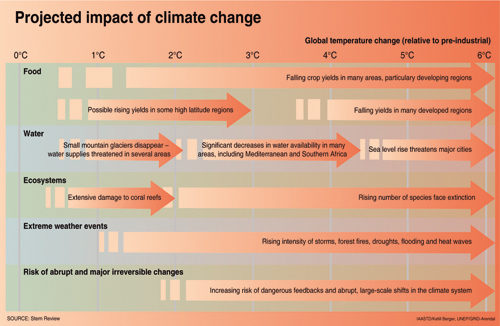

Figure 4.2 Impacts of a warmer climate.

Source Stern Review

Ecosystems do not only supply food, water, seed, fuel, medicines and building materials; they also support human society, culture, identity and community. They also play a part in the regulation of climate and water, air and soil cycles, in resistance to disease, and in protection against extreme weather. All these functions are known as ecosystem services. In principle, the Earth’s biodiversity and ecosystem services can provide us with a perpetual supply of renewable resources. They provide a basis for long-term value creation, and are a key to the solution of many problems, both now and in the future. Ecosystems can also provide us with new medicines and new species that are suitable for agriculture. It is estimated that only one-tenth of the Earth’s plants have so far been investigated with a view to their potential for medical or agricultural purposes.

However, species are being lost rapidly. A review of the most important causes of biodiversity loss shows that habitats are being destroyed by logging, agriculture and infrastructure development. Fragmented and degraded habitats are less able to withstand natural disasters and climate change than more continuous areas of habitat. Biodiversity is also reduced by overfishing and competition from alien species. Depending on the speed and scale of global warming, climate change may also constitute a threat to biodiversity.

Some hazardous chemicals are a serious threat to biodiversity, food supplies and the health of future generations. These are substances that do not break down readily in the environment and are therefore extremely persistent once they have been released. They can be transported over long distances from the source of pollution by air and ocean currents, and their concentrations build up along food chains. Such substances are a growing environmental problem in developing countries, many of which lack adequate systems for the control and management of chemicals. At the same time, the chemical industry is growing rapidly in developing countries. In China and India, for example, chemical production volumes is expected to grow by 10.5 per cent and 8 per cent respectively in the next ten years. At the same time, there is a tendency for polluting industries to move to developing countries and for developed countries to send large quantities of hazardous waste to developing countries.

Cooperation under the multilateral environmental agreements is a key part of the Government’s efforts to safeguard our shared environment and our livelihoods. The Norwegian Action Plan for Environment in Development Cooperation provides guidelines for Norway’s environment-related development efforts in poor countries. Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative is a major effort to secure the inclusion of emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in a new global climate regime and to safeguard other environmental assets. The Government is also seeking to strengthen the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and particularly its core functions, which are monitoring the state of the global environment and providing recommendations on the management of natural resources.

Much of the world’s genetic diversity is found in developing countries, and the policies these countries pursue will therefore be important in safeguarding ecosystems and genetic resources. Every country has to make difficult decisions about the balance between growth, conservation and use, but most poor countries will perceive the development challenges they are facing as more urgent than management of the natural environment. Moreover, many of these countries have insufficient resources to give priority to specific conservation measures. Negotiations are currently taking place under the Convention on Biological Diversity on an international regime for access to genetic resources and benefit-sharing, and the outcome will have an important bearing on the ability and willingness of poor countries to protect biodiversity. The international community must also take more responsibility for ensuring the necessary funding for environmental protection. One possibility that the Government is reviewing further is to provide direct compensation for the maintenance of ecosystem services.

The Government will:

support the conservation and sustainable use of areas and ecosystems of global importance

seek to ensure transparency in the management of natural resources and that local communities, including indigenous peoples, have access and rights to land and resources

support the implementation of multilateral agreements on chemicals, natural resources and biodiversity, the marine environment and marine resources

support the establishment of a UN panel on natural resources, biodiversity and ecosystem services under UNEP

work towards an international agreement on access to genetic resources and benefit-sharing under the Convention on Biological Diversity

contribute to the further development of mechanisms for payment for ecosystem services.

4.2 Climate change is making the development process more difficult

Signs of climate change – changes on various scales in all kinds of natural phenomena – are being observed all over the world. However, some of the most serious changes that will have the most immediate impact on large population groups are related to water – either too much or too little water.

Africa will experience more drought and thus more difficult growing conditions. In some countries, yields of crops that are dependent on rain water may be reduced by half. In Central and South Asia, yields may drop by up to 30 per cent between now and 2025. On the other hand, yields may rise for a time in temperate areas as a result of higher temperatures. The Himalayan glaciers are melting, affecting large groups of people. More frequent and more severe flooding will be a problem in the major low-lying river deltas.

About half of the world’s population lives in coastal areas where rising sea level and extreme weather will have negative impacts on fisheries, tourism, infrastructure, agriculture and access to fresh water. Even a 2 °C rise in temperature will cause a rise in sea level that would make several small island states uninhabitable.

Textbox 4.1 Climate change in the Himalaya region

Ice and snow in the Himalaya-Hindu Kush region, a continuous mountain system covering almost 3.5 million km2 and stretching through eight different countries, supplies a fifth of the world’s population with water for drinking, household use, irrigation and electricity production. But the ecosystem balance in the area has been disturbed, and this affects both the people who live in the mountains and those who live in the fertile plains below. The IPCC has shown that as a result of global warming, the «water tower» of Asia is shrinking. The main glaciers are retreating, and smaller glaciers are disappearing altogether. Pastureland is turning into desert. In some areas, flooding is becoming more frequent and more severe, while in others, life-giving rivers are gradually drying out. The glaciers that supply more than two-thirds of the water in the Ganges, considered a holy river by the Hindus, is melting three times as fast as it was 100 years ago. Many people fear that in a few decades, the Ganges will be almost dry outside the rainy season. In addition, the groundwater level is gradually dropping. If these trends continue, the fertile agricultural areas fed by the Ganges, the Yangtze and the Yellow River, which today make India and China the world’s leading producers of wheat and rice, will be severely affected. UNEP estimates that accelerated ice loss in the Himalaya-Hindu Kush may affect about 40 per cent of the world’s population.

Norway is supporting a regional initiative to provide information on climate change in the region. A five-year agreement has been signed for the period 2008–2013. Through CICERO (the Center for International Climate and Environmental Research) and UNEP/GRID-Arendal, Norway is also supporting a research project on the impacts of climate change in the Himalaya region.

A 2007 study from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) shows that Shanghai, Miami, New York, Alexandria and New Orleans will be among the cities where exposure to flooding grows most rapidly with rising sea level. Many other major cities will also be affected unless we can mitigate climate change.

The IPCC predicts that climate change will also affect the health of millions of people. For example, more outbreaks of disease are expected as a result of heatwaves, storms, wildfires and drought, and flooding often provides favourable conditions for communicable diseases. The greatest health risk is considered to be an increase in the distribution of diseases that are transmitted by vectors such as mosquitoes or ticks. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the incidence of diseases such as malaria and dengue fever will rise with the spread of vector organisms.

The IPCC has predicted a considerable rise in the number of climate refugees in the years ahead, but without putting a figure on the increase. According to the 2006 Stern Review, a conservative estimate is that 150–200 million people will be permanently displaced by 2050 as a result of rising sea level, more frequent storms and more intense drought. Other researchers point out that climate change will primarily result in displacement and conflict at fairly local level, not between countries. The scale and speed of temperature rise – whether it happens slowly and gradually or whether we reach tipping points – will have a decisive effect on the scale of the refugee problem and the conflict potential associated with climate change.

The Government will:

take part in efforts to identify the direct and indirect impacts of climate change on countries and regions.

4.3 Common but differentiated responsibilities in climate policy

The fight against climate change is a global responsibility. It can only be won if the developed countries take the lead and demonstrate that environmentally sound economic development is possible. So far, these countries are also largely responsible for man-made greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, the OECD countries have the largest financial and technological resources. This is reflected in the principle of «common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities» set out in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

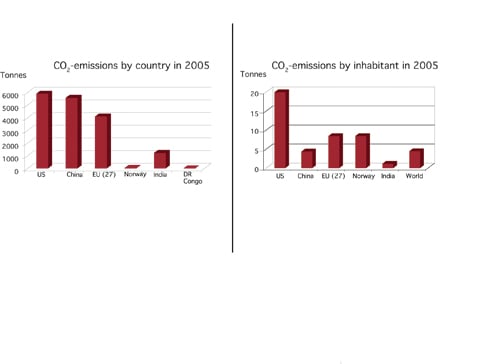

Figure 4.3 CO2 emissions

Source The diagrams show that in 2005, China was the second-largest emitter of CO2 in the world, just behind the US. China’s emissions are growing rapidly, and China has probably now overtaken the US as the world’s largest CO2 emitter. However, emissions per inhabitant are still much lower in China and India.Source: World Resources Institute and CICERO

At the moment, countries that have emission commitments under the Kyoto Protocol are responsible for about 30 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, but this proportion is dropping. This means that it will not be possible to achieve the necessary cuts in emissions unless developing countries, particularly those where emissions are high or rising rapidly, also pull their weight. Annual energy-related greenhouse gas emissions in middle-income countries are rising rapidly, and are now higher than those from developed countries. However, it is also crucial for the US to be part of the political leadership for global climate policy. Unless the US takes the lead, it will be difficult to persuade major developing countries to take the necessary steps to limit their emissions. The signals from the Obama administration indicate that the US is prepared to take this responsibility.

It is a major challenge to find ways of ensuring that economic and social development can take place in poor countries without too great a rise in their greenhouse gas emissions. The only way forward is to facilitate a path of development based on recent knowledge and technology. This can make it possible to leapfrog some of the phases involving environmentally harmful technology that the developed countries have been through.

Textbox 4.2 No more CO2 than Western countries

«I can promise that India’s per capita CO2 emissions will never be higher than in Western countries.»

Source Indian Finance Minister Chidambaram speaking to Minister of the Environment and International Development Erik Solheim during the Bali climate summit in 2007

To achieve this, earlier pledges to the developing countries on funding and technological cooperation must be honoured. The international climate change negotiations under the Climate Change Convention and the Kyoto Protocol have so far involved a tug-of-war on the distribution of burdens and rights, including the issue of how much responsibility the rich countries have for funding climate-related measures and transferring technology to developing countries that are themselves experiencing rapid growth.

The basis for the Government’s overall climate strategy at home and abroad was set out in the 2007 white paper on Norwegian climate policy (Report No. 34 (2006–2007) to the Storting) and the agreement on Norwegian climate policy reached by most of the political parties in January 2008. Allocations to the Government’s development and climate policy initiatives have been increased in the 2008 and 2009 budgets. Norway’s main priorities are reducing deforestation and forest degradation, clean energy, and the development of technology for carbon capture and storage. The aim is to reduce emissions in order to allow for the necessary increase in energy use in developing countries.

Norway will seek to foster interest in partner countries in sustainable natural resource management, low-carbon energy solutions, halting deforestation, adaptation to climate change and prevention of environmental damage. However, policy development is the responsibility of individual countries themselves. While other countries cannot take over the process of policy development in poor countries, the international community and countries such as Norway are able and willing to provide expertise and funding.

Massive support for climate change measures is also important as a way of increasing developing countries’ willingness and ability to take on commitments in a future global climate regime. Norway is working closely with key countries in the international climate negotiations. The African perspective has not yet been given sufficient room in the climate negotiations. Adaptation is the main challenge for Africa, but there are strong indications that Africa too can combine sustainable development for its own people with emissions reductions of importance for the global climate. There is a considerable potential for reducing emissions related to changes in land use and deforestation in several of the least developed countries.

African governments have started an important political process with a view to defining a joint platform for their participation in the international climate dialogue. They have adopted Africa’s Climate Roadmap, which initially deals with the dialogue up to the Copenhagen climate summit in December 2009. The Climate Roadmap puts the environment and agro-forestry at the heart of the climate negotiations, and at the same time sets out ways of reducing poverty, promoting energy security and safeguarding African ecosystems, landscapes and livelihoods. Norway wishes to support this African climate process.

The Government will:

work towards a climate agreement that ensures that global warming is limited to no more than 2 °C

promote the interests of the poorest and most vulnerable countries in the climate negotiations

support the implementation of Africa’s Climate Roadmap.

4.4 Clean energy

Rising energy use is both a result of and a key factor in development. The International Energy Agency believes that fossil fuels will remain the dominant global source of energy up to 2030. A sharp rise in consumption of fossil fuels is not compatible with limiting climate change. This means that a low-carbon development path and the use of energy from renewable sources must be given high priority.

Figure 4.4 Solar power will be a key energy source in the future, as here in Afghanistan.

Source Photo: Norwegian Church Aid

Today, some 1.6 billion people do not have access to electricity or other modern energy services. Lack of access to energy is one of the most important obstacles to poverty reduction. Energy is now more essential than ever, because energy is a key factor for participation in the globalised business sector and for access to global knowledge through the Internet and other media, and also for building resilience and the capacity to adapt to climate change.

Despite the fact that world energy production has never been higher, it is struggling to keep pace with economic development in some developing countries and with the general rise in population. According to the World Bank, China is already increasing its energy supplies by more in a fortnight than all the 47 sub-Saharan countries (with the exception of South Africa) do in a year. The type of energy infrastructure chosen will be highly significant for the outcome of the fight against climate change.

The choice of energy infrastructure will be determined by factors that differ from one country to another. In India, energy use per inhabitant is expected to remain at a relatively low level, and the country will also be able to limit its emissions if its plans for energy efficiency and decentralised renewable energy supplies are successful. India will also be able to make use of environmentally friendly hydropower in the Himalayas, even though ice-melt is creating uncertainty about trends in river levels.

Figure 4.5 Hydropower is an important energy source in Nepal. Norwegian expertise is much in demand.

Source Photo: Ken Opprann

In general, the clean forms of energy are too expensive and access to them is too difficult in comparison with energy from biomass, coal and kerosene. Many poor and middle-income countries find it simpler, quicker and to some extent cheaper to concentrate on oil- and coal-based power supplies rather than on energy efficiency or renewable energy sources such as hydropower or solar and wind power. In many developing countries, biomass is still the dominant energy source. Most people south of the Sahara will continue to use wood and charcoal for cooking in the near future. Unfortunately, these tend to be used inefficiently and in ways that cause local damage to ecoystems.

Africa has considerable undeveloped hydropower resources that could meet a large proportion of the continent’s energy needs. Major infrastructure projects – which must also include infrastructure for electricity distribution – will require stronger regional cooperation. Hydropower installations that are built with storage reservoirs can also provide water for irrigation and can be used for flood control and regulation of water flow in connection with adaptation to climate change. However, hydropower production is vulnerable to changes in precipitation, and can have negative social impacts and impacts on biodiversity. Conditions for solar power production are also very favourable in large parts of Africa. As the costs of solar power production fall, it offers particular potential for electrification in rural areas and in areas that are not on the grid. In addition, conditions for using geothermal energy (heat from within the earth) are favourable in some African countries.

As a region, Africa now has the opportunity to choose a planned, sustainable, robust low-carbon path of development. The International Energy Agency considers promoting renewable energy sources and energy efficiency to be one of the most cost-effective ways of increasing access to energy and at the same time reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The main task for Africa’s cooperation partners will be to provide a suitable framework and support for a sustainable and less vulnerable path of development based on clean energy.

Textbox 4.3 Experience gained by SN Power

Through the development of SN Power, which is owned by Norfund and Statkraft, Norway made an early start in investing in energy production in developing countries. The company’s portfolio has performed satisfactorily, and it has built up a great deal of experience that will be valuable in promoting greater investment in clean energy. Other power companies and various types of investors are showing an interest in this market.

In January 2009, a subsidiary of SN Power was established to intensify energy-related efforts in poor countries. This is a priority task but one that requires special planning and follow-up. SN Power AfriCA is to focus on energy investments in Africa and Central America. Efforts are being made to widen ownership of this company beyond Norfund and Statkraft, which will require mobilisation of private capital from Norwegian energy companies.

Environmentally sound solutions must also be cost-effective. Good, energy-effective technology may require higher investments initially, but such investments will generally be economically sound and commercially profitable in the long term. Developing countries are already paying a relatively high price per energy unit. It will therefore be important to shift energy demand to cheaper, renewable or more energy-efficient technologies. We should draw these countries’ attention to all the advantages of making use of their own renewable energy resources – in relation to public health, national energy security and reduced economic dependence on international oil prices.

Adaptations of the best technology, products, services and organisation models from developed countries can also promote sustainable development.

Textbox 4.4 Global Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Fund

The Government has committed NOK 80 million to the new Global Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Fund (GEEREF). This is a public-private partnership initiated by the European Commission, and Norway and Germany are the first two public donors to the fund. Altogether, the European Commision, Germany and Norway have undertaken to contribute EUR 100 million to the fund in the next four years. The purpose is to attract commercial capital for investments in climate-related measures and clean energy. Private investors will be given priority when returns on the fund are allocated. Any returns on contributions from public investors will be re-invested in the fund.

Norway’s role

As an energy nation, Norway is well placed to assist developing countries in their efforts to address energy-related challenges. This is part of the backdrop to our Clean Energy for Development initiative, which is intended to provide a framework for all Norwegian aid in this field. The initiative includes poverty-reduction projects, for example on electrification in rural areas using solar power, more efficient wood-burning stoves and improved charcoal production, as well as larger-scale projects such as hydropower developments, wind farms and solar farms connected to the electricity grid. The initiative will also involve stepping up Norway’s energy efficiency efforts, since this is a way of increasing the energy supply quickly without the side effects associated with all other types of new energy capacity, and will also help to prevent development that is associated with unnecessarily high levels of energy use.

Bilateral energy cooperation is in principle neutral with regard to technology choices. Norway’s contributions should be based on demand, and on countries’ own plans and priorities. The demand is often related to hydropower, which is the field where Norway has most expertise to offer, and a highly-developed industry that is interested in taking part in projects in developing countries. Norway can be a useful partner for countries that are interested in hydropower as an energy solution. But Norway is also winning recognition as a partner in solar technology, and this is being used actively in development assistance. Norway’s efforts in these areas can provide valuable technology and know-how, and projects benefit from the equipment, knowledge and training provided by the business sector. Strategic use of aid funding in combination with industry expertise will provide major benefits.

In multilateral energy cooperation, Norway focuses on making use of the comparative advantages of different organisations, seeking to ensure that projects complement each other, and encouraging the closest possible collaboration. The development banks are an important channel for funding efforts to improve access to energy and energy efficiency measures. The World Bank is in a particularly good position in this respect, because it operates both at country and global level, is engaged in most sectors, and has a variety of tools at its disposal – grants, loans and investments. The bank can encourage the private sector to invest in climate friendly energy and technology, and can lower the threshold for investing in countries where framework conditions are difficult and the level of risk is high.

Conditions for energy investments have improved considerably in a number of poor countries in recent years, and many developing countries can now provide a stable political climate for investors. Profitability has also improved because economic growth is creating a growing demand for energy, and because efforts to promote reform in a range of sectors, strengthen legislation and build up institutions have given results in a number of countries. However, energy projects in developing countries are complex, and the level of risk is still higher than in richer countries. Substantial public funding is needed to encourage private investment. Public funding reduces some of the risk factors for private investors. The financial crisis has resulted in uncertainty about the scale of private investments, particularly in poor countries, and this highlights the need for public funding.

Many of the respondents to the consultation on the report of the Policy Coherence Commission have suggested that a small share of the Government Pension Fund – Global should be earmarked for new investments in environmental technology or in developing countries. This and other proposals related to the fund will be considered in connection with the Government’s evaluation and revision of the ethical guidelines for the Government Pension Fund – Global.

The Government will:

use aid funding strategically to achieve rapid energy-related technological advances in developing countries

give higher priority to energy efficiency measures and work towards strategic energy planning in development cooperation

use aid and other public funding catalytically to trigger private investments in clean energy.

4.5 Deforestation

Forests are a resource of enormous value at global, national and local level. Millions of poor people are dependent on forests for their livelihoods. Forests provide services such as water storage, flood control, food and medicines, and are home to much of the world’s biological heritage. Forests also store carbon and will therefore be part of the solution to the problem of climate change.

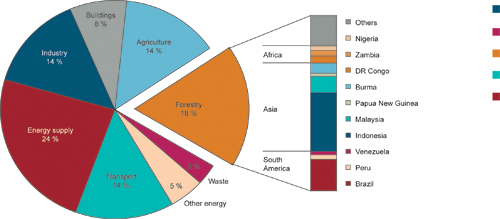

Emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries account for about 20 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions today. Conservation of natural forests is a cost-effective way of avoiding CO2 emissions. Afforestation and reforestation also reduce CO2 emissions, and are the only types of forest-related projects that are approved for use under the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism. Emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries are not included in the Climate Change Convention or the Kyoto Protocol. Norway is working towards the inclusion of commitments and mechanisms to reduce emissions from deforestation in developing countries in a global climate change regime for the period after 2012. However, the scale of these emissions makes it important to start forest-related projects as soon as possible, before a new agreement is in place.

Drivers of deforestation

Deforestation is not simply due to a lack of incentives to protect forests: the causes are complex and related to various alliances and interests. We will have no guarantee that funds or market mechanisms intended to reduce emissions from deforestation and land-use change will work unless we take into account issues relating to power and capital in individual countries. The political will in forest countries to deal with the underlying causes of deforestation will be of crucial importance.

Globally, the most important driver of deforestation is the need for new agricultural areas. Grants for converting forest to soy and oil palm plantations encourage deforestation. So does the often over-dimensioned pulp and paper industry. In many cases, plantations are unable to provide sufficient timber as raw material, and in Indonesia it is estimated that more than half comes from natural forests and protected areas. Organised crime and corruption play an important role in deforestation. Forest fires are responsible for large greenhouse gas emissions every year. Deliberate burning is the simplest way of clearing forest for other purposes.

In Central African countries, many years of war have kept the deforestation rate low. However, this could change quickly, since many licences have been issued for commercial logging.

In Brazil, there are unresolved tensions between conservation and development interests. It is estimated that at least 60 per cent of all logging in the Amazon basin is illegal – in Indonesia, the figure may be higher than 70 per cent. The World Bank estimates that this costs tropical forest countries USD 15 million per year in lost revenues and economic growth, or more than eight times the aid provided for sustainable forest management. The situation is exacerbated by a lack of transparency in the complicated and often corrupt systems for issuing licences and inadequate monitoring of compliance with licences.

The EU and the World Bank have started processes in relevant regions to reduce illegal logging and trade in tropical timber. These may be of crucial importance in improving enforcement of the legislation and facilitating better governance of the forest sector. However, legal logging is not necessarily sustainable in social, ecological or economic terms. There are several certification systems, but they do not provide adequate guarantees that tropical forest products are sustainable. To achieve sustainable forestry and maintain the capacity of forests to absorb carbon, they must be based on the principles of sustainable forest management.

Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative

Norway’s Climate and Forest Initiative is a strategic approach to dealing with climate change. It is intended to bring about substantial, verifiable reductions in emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries. The aim is for these emissions to be regulated in a new international climate regime, and projects will be chosen with a view to gaining experience that can be used in this connection.

Figure 4.6 Sources of greenhouse gas emissions

Source IPCC; WRI/CAIT

In line with the decision made at the climate summit in Bali in 2007, most projects in the preliminary phase of the initiative are demonstration and pilot projects, and focus on capacity building and support for the development of national strategies. If a new and more comprehensive climate regime is put in place for the period after 2012, it may be possible to carry out large-scale projects to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation.

A credible system for monitoring and reporting emissions is essential if measures to reduce deforestation are to be included in a new climate regime. Through the initiative, the Government wishes to play a part in developing international and national capacity for measuring and verifying emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. Emissions must be reported at national level to ensure that reducing logging in one area does not result in more logging in another and thus cause carbon leakage. It is also important to prevent carbon leakage at international level, between countries and regions.

Efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation are inextricably linked with poverty reduction and sustainable economic development. This recognition is an important basis for the initiative. In the long term, it will be impossible to achieve permanent global reductions in emissions from deforestation without ensuring sustainable economic development for people who live in and around the forests. Financial mechanisms, compensation for ecosystem services, formalisation of user and property rights and rights to the carbon in forests, and the productivity of surrounding agricultural areas are all factors that will be very important for the long-term results of the initiative and for winning developing countries’ support for the inclusion of emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in a new climate regime.

The initiative includes activities in all three of the most important tropical rain forest regions. Examples are direct contributions to the Amazon Fund in Brazil, and cooperation with several other donors, including the UK via the African Development Bank, in the Congo basin. Norway is also providing support through the UN for the preparation of national strategies to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in Papua New Guinea and Indonesia. In addition, there are activities in areas of dry tropical forest and savanna, including cooperation with Tanzania on emissions reduction and the restoration of deforested areas.

Norway provides much of its funding through multilateral channels, including the UN and the World Bank. Norway has also been instrumental in bringing about cooperation between the relevant UN organisations on the UN Collaborative Programme on Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (UN REDD). In the first phase of the programme, funding is primarily being used for capacity- and competence-building, while in later phases the focus will shift to the implementation of national plans for reducing deforestation and for sustainable forest management.

Figure 4.7 Half of the world’s remaining tropical rain forest is in the Amazon basin. Brazil is therefore an important climate policy partner.

Source Photo: Espen Røst

We will not be able to achieve a new climate agreement if poor countries are left to meet the costs of reducing emissions from deforestation by themselves. Large-scale international transfers of capital will be needed. Compensation for avoiding deforestation must be high enough to compete with the profits that can be made from existing ways of using forests.

The Government will:

work towards rapid, cost-effective and verifiable reductions in greenhouse gas emissions from forest areas

promote the conservation of natural forests to ensure carbon storage, protect poor people and indigenous peoples, and conserve biodiversity

work towards the inclusion of emissions from deforestation in a new international climate regime.

4.6 Adaptation to climate change

Throughout history, people have had to develop strategies to adapt to variations in the climate. However, given the scale, pace and unpredictability of the changes that are now taking place, it seems unlikely that traditional adaptation strategies will be adequate in the future. Rapid climate change will particularly affect public health, industrial structure and settlement patterns. Large-scale changes in water supplies and rainfall will affect food security and infrastructure. But slower and less obvious changes may also have major impacts on human health and the economy, especially in societies where adaptation capacity is low. The social and political dimensions of climate change are often underestimated.

Textbox 4.5 The role of indigenous peoples in sustainable forest management

One billion people live in or near forests and depend on them for their livelihoods. A very large proportion of the world’s roughly 350 million indigenous people have strong links and traditional rights to forests. However, they are often unable to assert or formalise their right to gain a livelihood from forests, or contribute to sustainable forest management. Indigenous peoples do not necessarily protect forests, but under the right circumstances and if they have statutory rights, many indigenous peoples will see that it is in their own interests to play a part in maintaining forests and the biodiversity on which they depend for their livelihoods.

Norway has ratified Convention (No. 169) concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries, which was adopted by the International Labour Organisation in 1989, and also, with certain reservations, endorsed the UN declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples (2007). However, only a few of the most important tropical forest countries have done so. In many of these countries, indigenous peoples have no specific rights at all. In others, their traditional rights to particular areas of forest are disregarded in connection with infrastructure development, prospecting for minerals, logging or conversion of land for agriculture. Thus, there is a disparity between the rights indigenous peoples have under international law and the role they are allowed to play in practice in managing the forests on which they depend.

Where indigenous peoples’ rights are recognised, for example in indigenous peoples’ territories in Brazil, we see that they protect forests in conservation areas more effectively than the national authorities. Unless indigenous peoples and local communities are given a greater role to play in forest management, there is a serious risk that more extensive climate-related restrictions on the use of tropical forests in regions such as Central Africa and Southeast Asia will put further restrictions on resource use by these groups. This may also reduce their interest in maintaining forests and force more of them into illegal logging. This in turn would make it less likely that cuts in emissions achieved through an international mechanism would be permanent.

The severity of the impacts of climate change will depend on society’s and individuals’ vulnerability and adaptation capacity. Adaptation capacity is determined by access to capital, labour, knowledge, health services, transport and communications, social relations and networks. Factors such as good governance, access to resources and an active civil society are important. Measures to strengthen a society’s capacity to take joint action will boost its ability to deal with climate change and natural disasters.

It is also important to make use of women’s knowledge of local natural resources, food security and ways of reducing various forms of vulnerability in adaptation efforts.

2007 was the first year when globally, more people lived in urban than in rural areas. According to the World Bank, 75 per cent of the world’s poor still live in rural areas. Nevertheless, 80 per cent of the world’s urban population will be living in developing countries by 2030. By then, seven-tenths of the world population will live in Africa and Asia. According to the UN, much of the growth in world population during this century will consist of poor people who will be in a very vulnerable situation as regards access to food and energy, climate change, and other factors. Growing towns and cities urgently need to draw up plans to reduce vulnerability, take steps towards a low-carbon future, and choose climate-friendly alternatives for infastructure, services and markets.

The impacts of climate change must be considered in the context of other development processes. Adaptation strategies must be based on countries’ own development strategies. Climate change must be taken into account in plans and strategies for agriculture, water resource management, forest management, energy, health, and knowledge and education. The integration of climate change considerations into social planning at local and national level will be a key to successful adaptation. Adaptation efforts must also reduce the vulnerability of the urban poor.

Figure 4.8 Clean water is in short supply in many developing countries

Source Photo: Fredrik Schjander

Incorporating mitigation and adaptation measures into development policy is an important task internationally. Many development measures also help to reduce vulnerability and increase adaptation capacity. However, more attention must be paid to reducing vulnerability, improving the capacity to cope with disasters, and participation at local level. This was also highlighted by the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs in its recommendations to the Storting on the white paper Norwegian Policy on the Prevention of Humanitarian Crises (Report No. 9 (2007–2008) to the Storting). Particularly at the present stage, when we are negotiating a new global climate regime, it is important to promote a broad approach to adaptation to climate change and disaster prevention. We must invest in the whole range of adaptation measures, from emergency preparedness and crisis management to reconstruction and long-term development efforts.

The Government will:

encourage partner countries to include adaptation to climate change in social planning and national development strategies, in order to build resilience to climate change

promote the integration of adaptation to climate change and the prevention of humanitarian crises into development cooperation

seek to strengthen women’s influence on natural resource management.

4.7 The costs of adaptation and mitigation

The costs involved in dealing with the problem of climate change will be formidable. There are major challenges involved in mobilising the resources that will be needed to stabilise the climate system, which is a global public good. This is not only a matter of willingness and ability. It will also require political and economic creativity and innovation. An important first step is to distinguish between the costs of essential measures to cut greenhouse gas emissions and essential adaptation measures. A suitable framework must be provided to encourage business and industry globally to play a key role in developing and deploying emission abatement technology. Governments must play a more direct role in funding and implementing adaptation measures.

The scale of the challenges involved in adaptation varies greatly from one country to another. Far-reaching measures will be needed in countries that have not contributed significantly to greenhouse gas emissions and that do not have the resources to fund the necessary adaptation measures. How much funding should be provided for adaptation measures and how funds should be managed are key topics in the climate negotiations. A special Adaptation Fund has been established under the Climate Change Convention/Kyoto Protocol, and the Government keeps the need to increase allocations to this and the other climate funds under review. It is important to ensure that the Adaptation Fund starts to invest in specific projects that can make a constructive contribution to international efforts. Norway is one of the largest voluntary contributors to activities organised by the Convention secretariat to build up expertise on climate negotiations and assist poor countries in developing and refining their positions in the climate negotiations.

Norway is contributing to capacity building for environment and climate issues through support to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and the World Bank. These organisations are working together to put African countries in a better position to make use of the funding opportunities offered by the Clean Development Mechanism. The Global Environment Facility (GEF), which is the financial mechanism for the main multilateral environmental agreements, allocates project funds to the most appropriate organisations. The GEF provides support for all aspects of climate-related work, and assesses the results on the basis of the priorities set by the conferences of the parties for each convention.

Textbox 4.6 Adaptation to climate change in Bangladesh

Bangladesh is particularly vulnerable to climate change, since it consists largely of a low-lying delta situated between the Bay of Bengal, which is regularly hit by cyclones, and the melting glaciers of the Himalayas. The country is heavily dependent on agriculture and very densely populated. Climate change is already having an impact here. Flooding is becoming more severe, and cyclones are stronger and more unpredictable. The scale of the damage has increased. Large areas of formerly productive rice paddies are being flooded by sea water, making rice production impossible. Erosion along rivers has worsened, and houses are constantly having to be moved to prevent them from being washed away.

The Bangladeshi authorities have been working systematically in recent years to prevent disasters, introduce better early warning systems, build enough cyclone and flood shelters, and adapt to climate change, both now and in the future. The problems are overwheming, but a great deal has been achieved. New rice varieties have been developed that tolerate higher salinity. In many places, farmers have switched from growing rice to crab farming. Construction techniques have been changed so that houses are more robust than before, and often built on artificially raised ground to reduce the risk that they will be destroyed by flooding. Steps have been taken to prevent landslides along river banks. Families are keeping ducks instead of chickens. Floating-bed cultivation techniques have been developed – floating platforms are constructed on which many kinds of crops can be grown, including tomatoes and onions. This prevents crops from being lost during floods.

Good progress has also been made in developing early warning and evacuation systems. Early warning systems have been improved and more cyclone and flood shelters are available. In many cases, the shelters also accommodate livestock, which makes it easier for farmers to agree to evacuation.

Bangladesh has taken climate change seriously, and other countries have much to learn from its example. Systematic efforts do give results. Cyclone Sidr in November 2007 was one of the strongest to strike Bangladesh for many years, but caused far fewer deaths than similar storms have done earlier, and fewer than cyclones in the neighbouring country of Burma.

However, it is obvious that adaptation to climate change will require far greater resources than the various funds can provide. Nor will development aid be sufficient. Norway is cooperating with other actors, including the EU, to put in place public-private partnerships to mobilise capital. Adaptation requires a long-term perspective and predictable funding on an adequate scale, beyond the contribution made by the existing financial mechanisms. The question of future funding is therefore of key importance in the negotiations on a new climate agreement to be concluded in Copenhagen at the end of 2009.

The framework conditions must be designed to take into account the business sector’s natural focus on profitability and new market opportunities, so that this sector can become the main driver of a low-carbon path of development. For this to happen, there must be a price on carbon, and the Government is therefore working towards the establishment of a global carbon price. A high carbon price will also encourage the development of alternative forms of energy. Dealing with the problem of climate change will require broad-based efforts by the public authorities, including strategic use of aid to ensure that renewable technology is developed and made commercially available in all countries.

At present, the cost of emitting carbon is too low to generate the rapid technological advances needed. Despite the establishment of regional emissions trading markets (for example the EU scheme), and despite the fact that both the Kyoto Protocol and national policy instruments to cut emissions send price signals that encourage change and innovation, there is still great uncertainty about how these systems will develop in the future. The long-term price signals must therefore be strengthened.

Textbox 4.7 Norwegian proposal for auctioning of emission allowances

Norway is working towards the successful conclusion of an international climate agreement to follow on from the Kyoto Protocol, to be signed at the climate summit in Copenhagen in December 2009. One of the key questions to be resolved is how adaptation measures are to be funded in poor countries. Norway has put forward a proposal for a system that could release large-scale funding for adaptation in poor, vulnerable countries. Briefly, the proposal is that, assuming the new climate agreement is based on a cap-and-trade system, like the Kyoto Protocol, a certain proportion of the total quantity of emission allowances should be auctioned internationally. The revenues should be used among other things to fund adaptation measures in the most vulnerable countries and regions. These revenues would vary depending on the size of the emissions trading market (which is determined by where the emissions ceiling is set) and the proportion of the allowances auctioned. But this model could provide a predictable and adequate flow of income.

The World Bank has established an innovative carbon fund, the Carbon Partnership Facility, as a signal that the carbon market will continue to operate after 2012, even though a new climate agreement has not yet been achieved. The fund provides a guarantee for carbon purchases after 2012 through partnerships between future buyers and sellers. It also provides incentives to plan for the use of clean technology in major infrastructure projects that are being developed today. This will help in the establishment of a long-term carbon market, and is an initiative Norway supports.

The Government’s initiative for the development of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology is relevant in both the climate and the development context. The goal is for such technology to be commercially available throughout the world, so that it results in cuts in greenhouse gas emissions that really make a difference and allows for an increase in energy use, particularly in developing countries. In the current situation, CCS appears to be necessary as a supplement to renewable energy and energy efficiency. The greatest potential for using this technology is in connection with large point sources of emissions and in countries where emissions are rising rapidly. Spreading CCS technology to developing countries is part of the Government’s long-term strategy, but for now the main focus is on projects at national and international level with a view to developing the technology itself. It may also be appropriate to provide developing countries with technical assistance and support for project planning and risk reduction in connection with CCS. Certain activities with clear development effects will be eligible for funding over the development budget.

Under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), developed countries can fund projects to reduce emissions in developing countries and thus acquire emission credits that can be offset against their emission commitments. Such projects can also contribute to sustainable development in recipient countries. It is up to recipient countries to determine whether this is the case. By the end of 2008, there were just under 1300 approved CDM projects, which are expected to generate emission credits corresponding to almost 1.4 billion tonnes of CO2.

Norwegian companies can make use of CDM emission credits to meet their commitments under the Norwegian emissions trading scheme. In addition, Norway intends to purchase a substantial number of emission credits as part of its efforts to meet its Kyoto commitment and its voluntary goal of strengthening this commitment. Currently, about NOK 7 billion has been allocated for this purpose. The Government is considering various approaches that could make the Clean Development Mechanism a more important source of funding for investments in Africa as well.

The Government will:

work towards international mechanisms to mobilise resources for reliable long-term funding of adaptation to climate change in developing countries

offer private-public partnerships to promote technology cooperation and transfer to developing countries

further develop an international framework that will make business and industry a driver in the development of a low-carbon society

take steps to ensure that Norway’s purchases of emission units through the Clean Development Mechanism are in line with our development policy goals

support projects to develop and deploy technologies for carbon capture and storage to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and allow for the necessary increase in energy use in developing countries.