6 Capital

The goal of increasing the developing countries’ share of global capital and economic growth is a key element of the fight against poverty. For the world as a whole, average gross domestic product per person (per capita GDP) in 2007 was almost USD 10 000, while in the 50 least developed countries it was less than USD 750.

Sound economic policy at the national level is vital for creating and strengthening processes that can provide a basis for sustainable social and economic development. However, in our globalised world, external factors are increasingly influencing national processes. Such factors may include participation in various international agreements, and other unpredictable factors, that do not fall within the scope of international arrangements. The financial crisis, which in a short period of time has resulted in dramatic changes in the economic outlook for both poor and rich countries, demonstrates just how closely interwoven national and global economic structures have become. There is broad international agreement that the interests of developing countries must be at the centre of efforts to cope with the financial crisis and the challenges arising from slower global growth.

Multinational enterprises control one quarter of the world’s GDP. One third of all world trade takes place internally in such enterprises. Every day, currency to a value of more than USD 3000 billion is bought and sold in foreign exchange markets. This is almost three times the world’s total annual defence spending. The forces of global capital are powerful, and have a strong influence on economic development in poor countries.

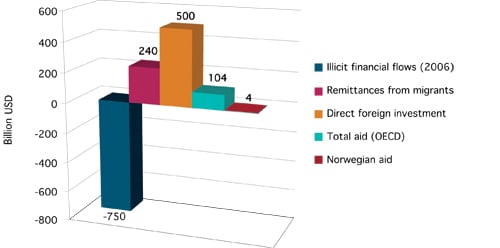

Figure 6.1 Important financial flows to developing countries, 2007.

Source Global Integrity 2009, World Bank 2008, UNCTAD 2008, OECD 2008

Foreign investment, trade revenues and remittances from migrants are the most important financial flows into poor countries. Official development assistance from OECD member countries totals about USD 100 billion a year. Payment for imported goods and services is the most important financial outflow from developing countries. Other important financial flows are repayment of foreign debt, accumulation of foreign reserves and repatriation of profit from foreign investments. In addition, there are substantial illict financial flows between countries and regions. Exact figures for illicit financial flows are hard to come by. However, estimates by the US think-tank Global Financial Integrity indicate that in 2006, the volume of illicit financial flows out of developing countries was at least USD 750 billion, and that the problem is growing.

Aid makes up only a small proportion of capital transfers to developing countries. However, aid is unique in that it can be channelled directly to projects that will have a real development effect. There is a pressing need for funding to strengthen areas such as health, education, gender equality and children’s rights, and this need cannot be met without the use of aid as part of an active development policy. The Government also intends to make greater strategic use of development policy tools and aid funding to steer large financial flows in a more development-friendly direction.

6.1 Foreign investment

Until recently, a strong world economy has helped to increase capital inflows to many developing countries. Foreign investors have shown great interest in new business initiatives. In Africa, the level of foreign investment more than tripled over a five-year period, and reached an estimated USD 27 billion in 2007. Investments in all developing countries in the same year totalled more than USD 300 billion. The largest investments have been made in middle-income countries and countries with large natural resources. The financial crisis and the downturn in the global economy have checked the growth in investments.

Figure 6.2 The financial crisis is affecting people all over the world. The Karachi Stock Exchange is no exception.

Source Photo: Asif Hassan/Scanpix

Growth in investment has positive effects on economic growth and employment. Rapid growth has also given many developing countries a historic opportunity to repay debt and accumulate foreign reserves. This enhances macroeconomic stability and gives more political space for choosing national development measures. However, the financial crisis has resulted in a sharp reduction in risk capital and rising capital costs. Providing a suitable framework for continued growth in investment in poor countries will therefore be an important development policy task in the years ahead. In these efforts, it is important to take into account the fact that developing countries are a heterogeneous group, and that their capacity to attract private investment varies. This is a good reason for giving priority to the least developed countries, with a special focus on Africa.

Countries with a stable political and administrative framework will generally attract more capital than unstable countries. The Norwegian Government is therefore giving priority to state-building as a key element of development policy, and an important tool for ensuring sustainable economic development. In many cases it is also relevant to reduce the political or commercial risk involved in investing in developing countries through support schemes for private sector development, for example through Norfund and GIEK. Aid can also be used to catalyse large-scale private-sector investment through public-private partnerships.

For poor countries, it will be important to find a balance so that regulation, bureaucracy and taxation do not stifle investment appetite and at the same time safeguard the economic gains from such investments. Foreign investment can contribute to new infrastructure, transfers of technology and market access, all of which benefit local business and industry. However, national authorities have an important role to play in opening the way for such positive ripple effects.

Many of the largest investments in developing countries are connected with the extraction of oil, gas and other minerals. The extractive industries are associated with large-scale capital investment, but only provide limited employment opportunities. In addition, they are based on the use of non-renewable resources. The gains from the extraction of such resources should therefore be regarded as wealth rather than ordinary revenues. The capacity of the authorities to regulate and tax such activities will therefore be of crucial importance in ensuring that investments contribute to sustainable economic growth and development in the country concerned. Norway has a great deal of experience to offer in this field. Through initiatives such as Oil for Development, Petrad, and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), the Government will ensure that developing countries are given access to Norwegian experience and expertise.

A growing number of Norwegian firms are investing directly in developing countries. Some of the largest are StatoilHydro, Telenor, Jotun and Statkraft. In 2006, Norwegian direct investment in developing countries totalled about NOK 115 billion. This is enough to make an important contribution to employment, revenues and economic growth. For example, Telenor has helped to create several hundred thousand jobs in Bangladesh. In 2007, the company paid NOK 2.7 billion in taxes to Bangladesh. In Angola, StatoilHydro’s activities generated tax revenues in excess of NOK 10 billion in 2007.

Figure 6.3 Angola’s oil resources have attracted large-scale foreign investment, some of it from Norwegian companies.

Source Photo: Christopher Olssøn/Littleimagebank

Corporate social responsibility

The Government wishes to encourage Norwegian business and industry to invest more in developing countries. However, we know that there is a high level of risk associated with investing in countries where governance is weak, both in financial terms and as regards a company’s reputation.

All companies operating abroad are expected to comply with the host country’s laws and regulations. However, many developing countries have inadequate legislation, weak governance, widespread poverty and corruption. In countries such as these, the way companies do business and demonstrate responsibility is of particular importance. This does not mean that companies should automatically assume responsibility for matters that are the province of the authorities in the countries concerned. It would be unreasonable to expect this of private companies, and it would not necessarily promote long-term development. The Government’s position is therefore that corporate social responsibility (CSR) involves companies integrating social and environmental concerns into their day-to-day operations, as well as in their dealings with stakeholders. CSR means what companies do on a voluntary basis beyond complying with existing legislation and rules in the country in which they are operating. Companies should promote positive social development through value creation and responsible business conduct, and by taking the local community and other stakeholders into consideration.

Most Norwegian companies are interested in promoting high ethical standards in their operations abroad. The costs of a loss of reputation are high. However, we know that it can be a difficult task to maintain the required standards. This is why the Government has presented the white paper Corporate social responsibility in a global economy (Report No. 10 (2008–2009) to the Storting). The white paper makes it clear that the Government expects Norwegian companies to play a part in setting high standards for CSR in developing countries. This means that they must respect human rights, uphold core labour standards, take environmental concerns into account, combat corruption, and maximise transparency in their international activities.

Indirect investment

Indirect investment, for example purchases of equities and other securities, has become an important source of capital for developing countries in recent years. In Africa alone, such transfers were worth about NOK 55 billion in 2007. In this context, the growth of large sovereign wealth funds such as the Norwegian Government Pension Fund – Global is an important development. Greater availability of investment capital opens up new opportunities, but also presents new challenges. Norway has given high priority to developing an ethical framework for investments by the Government Pension Fund – Global. However, not all countries consider the ethical dimension to be equally important. There has been concern internationally about the fact that certain funds show little transparency in their operations, and do not have systems for taking ethical considerations into account.

In an international evaluation of the largest sovereign wealth funds in terms of transparency and accountability, structure, governance and behaviour, the Government Pension Fund – Global was ranked as a world leader. To ensure that Norway can continue to contribute to high standards in the management of public securities investments, the Government has initiated an evaluation of the Ethical Guidelines for the Fund, including a public consultation involving a wide range of actors. This has resulted in a number of recommendations on how to increase the development policy importance of investments by the Government Pension Fund – Global, in much the same vein as the recommendations made in the report Coherent for development? (NOU 2008:14). The results of the evaluation and any proposals for changes to the Ethical Guidelines will be presented in the annual white paper on the Government Pension Fund in spring 2009.

At present, the Pension Fund has no assets invested in the least developed countries, but has made investments in a number of middle-income countries that are also recipients of Norwegian development cooperation. The World Bank has recommended that sovereign wealth funds should focus more on the least developed countries. The World Bank is currently developing a platform to facilitate sovereign wealth fund investment in Africa, South America and the Caribbean. Its proposals will be considered in connection with the evaluation of the Ethical Guidelines for the Norwegian Government Pension Fund – Global.

Table 7.1 Investments by the Government Pension Fund – Global in selected developing countries, 2007

| Country | NOK (million) |

|---|---|

| Brazil | 11 193 |

| South Africa | 7 205 |

| China | 6 959 |

| India | 1 881 |

Source Ministry of Finance, 2008

The Government will:

call on the private sector to increase its investments in developing countries and invite companies to enter into strategic partnerships in order to reduce the risk associated with such investments and improve their development impact

include cooperation on social responsibility as an important component in partnerships between public and private actors in developing countries

urge Norwegian companies operating in developing countries to demonstrate social responsibility and bring good business practices from their operations in Norway.

6.2 Illicit financial flows and tax havens

Illicit financial flows are cross-border financial transactions linked to illegal activities. The proceeds of organised crime such as trafficking in drugs, weapons and human beings account for a substantial proportion of illicit financial flows. Large sums of money also disappear through various types of fraud, corruption, bribery, smuggling and money laundering.

However, the largest share of illicit financial flows is related to commercial transactions, often within multinational companies, whose purpose is tax evasion. One method is abuse of transfer pricing, where exports and imports are incorrectly priced within a company, so that the profit can be recorded in secrecy jurisdictions, or tax havens, and not in the country where it should have been taxed. This type of mispricing is possible to detect by painstakingly going through customs and trade figures – provided that there is a recognised normal price for the goods in question, and that the discrepancy is large. It is very difficult to detect fraud of this kind in trade in services.

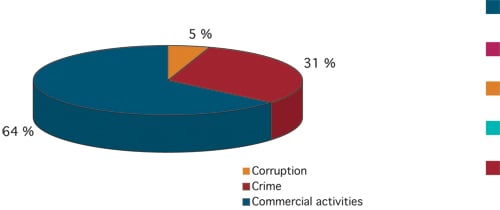

Figure 6.4 Illicit financial flows from developing countries.

Source Global Financial Integrity, 2007

To prevent tax evasion effectively requires sound legislation, well-functioning institutions and high administrative capacity. Many developing countries are therefore poorly equipped to prevent this kind of crime. Calculations show that illicit financial flows as a proportion of GDP are a greater problem in Africa than in other regions. However, the nominal value of the losses from such transactions is greatest in Asia.

The role of tax havens

Tax havens are a key factor in efforts to limit illicit financial flows. According to the OECD, three factors that characterise a tax haven are: the jurisdiction imposes no or only nominal taxes, it protects investors against tax authorities in other countries, and there is a lack of transparency about the tax structure and the companies that are registered. Tax havens attract both licit and illicit capital.

Every country has the right to determine tax rates for the individuals and companies that choose to reside in or register their businesses there. Problems arise when a state does not have adequate rules and regulations to prevent money laundering or breaches of other countries’ legislation. By refusing to ensure transparency and disclosure or assisting in the establishment of shell companies in order to conceal the real ownership of assets, tax havens make it difficult for the tax and police authorities in other countries to investigate this type of crime. The Government’s policy here is to strengthen international rules to prevent assets that are illegally appropriated from developing countries from being concealed or laundered in tax havens.

There are many different views on which countries and territories are tax havens. International lists include various types of jurisdictions, from the most secretive to those that are relatively open and cooperative. Some of the best known tax havens are small Caribbean islands. However, their operations often depend on activities in major financial centres such as New York, London, Singapore and Hong Kong. Professional advisers who assist companies to evade national legislation often operate from these.

Access to tax havens simplifies money laundering and makes it possible to deposit and transfer financial assets secretly. This affects all countries, but poor countries are hit much harder than rich ones. Developing countries have a limited tax base and an urgent need for public funding of basic services. Moreover, tax havens reduce disclosure and control of international financial flows. A lack of transparency allows government officials to build up fortunes abroad based on corruption and the theft of public assets. This can undermine confidence in democratic institutions.

Table 7.2 Jurisdictions that do not satisfy the OECD standards of transparency and effective exchange of information in tax matters

| Jurisdictions that are cooperating with the OECD on implementation of its standards | Uncooperative tax havens | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Anguilla | Isle of Man | St Kitts & Nevis | Andorra |

| Antigua and Barbuda | Jersey | St Vincent and the Grenadines | Liechtenstein |

| Aruba | Liberia | Turks & Caicos Islands | Monaco |

| Bahamas | Malta | US Virgin Islands | |

| Bahrain | Marshall Islands | OECD member states that have been urged to change rules on withholding information | |

| Belize | Mauritius | ||

| British Virgin Islands | Montserrat | ||

| Cayman Islands | Nauru | ||

| Cook Islands | Netherlands Antilles | Austria | |

| Cyprus | Niue | Luxembourg | |

| Dominica | Panama | Switzerland | |

| Gibraltar | San Marino | ||

| Grenada | Seychelles | ||

| Guernsey | St Lucia | ||

Source OECD, 2008

The existence of tax havens can also result in an undesirable form of competition between developing countries, based on low tax levels and with the aim of attracting foreign investment. This can be at the expense of a country’s ability to benefit from private sector development and economic growth. Helping such countries to increase their capacity to enforce legislation, collect taxes, and fight corruption and economic crime is given high priority in the Government’s development policy.

Global efforts required

However, the fight against illicit financial flows is primarily a global task, and requires global solutions. The Government intends to play a leading role in international efforts to prevent money laundering, tax evasion and other economic crime.

Norway, represented by the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Finance, plays an active role in international bodies that are combating money laundering and working towards transparency and compliance with international conventions, such as the Financial Action Task Force, the OECD and Interpol.

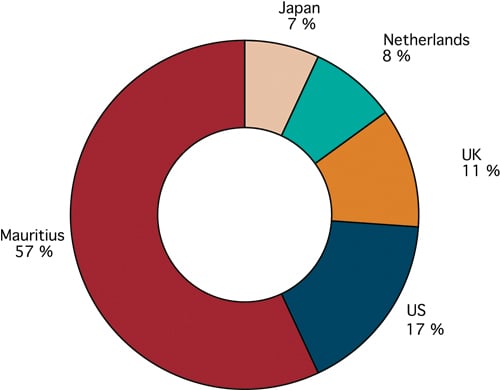

Figure 6.5 Foreign direct investment in India, by country of origin (1991–2007).

Source Reserve Bank of India, reproduced in Foreign Direct Investment in India, Confederation of Indian Industry, 2008

Norway has also headed an international task force on the development impact of illicit financial flows. Its recommendations were presented at the Doha Review Conference on Financing for Development organised by the UN. To keep up the momentum of this work, Norway has decided to provide funding for the new Task Force on Financial Integrity and Economic Development, which was launched in January 2009.

The Government appointed the Commission on Capital Flight from Developing Countries to assess Norway’s position regarding the use of tax havens. The Commission is due to report by 1 June 2009. It will make recommendations on how financial flows to and from developing countries via tax havens can be made more transparent, and how illicit financial flows and money laundering can be limited.

International rules aimed at combating corruption are being steadily improved. New instruments include conventions under the OECD and the Council of Europe. An important breakthrough was the conclusion of the UN Convention against Corruption, which entered into force in 2005. Negotiations on the convention were concluded remarkably quickly, and 126 countries have already ratified it. This is the first global instrument against corruption, and reflects the recognition by both developed and developing countries that dealing with corruption requires international solutions.

The existence of a global anti-corruption instrument is an opportunity for Norway to intensify its engagement in this field. The UN Convention provides a joint platform and a global standard that applies equally for all countries. Norway is playing a leading role in the establishment of an implementation mechanism to ensure that the Convention is put into practice.

In addition to fighting corruption, it is important to identify stolen assets from developing countries by means of corruption and ensure their return. In 2008, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the World Bank established the Stolen Assets Recovery Initiative to promote international commitments, knowledge and cooperation in this field.

The UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime entered into force in 2003. Its protocols deal with human trafficking, smuggling of migrants and illicit trade in firearms. Norway is playing a key role in establishing a monitoring mechanism for the convention. The Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings, which entered into force in 2008, is also important for Norway’s efforts in this area.

The Government will:

offer selected developing countries technical and financial support to strengthen their tax legislation, tax collection systems and anti-corruption efforts

maintain its focus on the need for new international rules to ensure disclosure and transparency in the international financial system and thus prevent illegal activities in tax havens

support research and analysis that can improve understanding of the scale of illicit financial flows and the methods and actors involved

cooperate with other countries and multilateral organisations to prevent illicit financial flows, and take steps for the return of assets removed from developing countries through corruption

promote universal adherence to and effective implementation of the UN Convention against Corruption

promote universal adherence to and implementation of the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and its protocols on human trafficking, smuggling of migrants and illicit trade in firearms.

6.3 Aid and new sources of financing for development

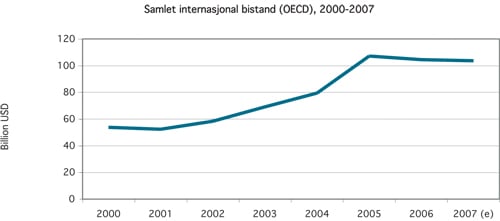

Aid from the OECD countries almost doubled in the period 2000–2005, greatly helped by rapid global growth. However, after successful debt relief initiatives, there has been a certain decline in aid compared with the record year 2005. This trend is in sharp contrast to pledges made by the international community on a number of occasions.

One result of the international financial crisis and the poorer outlook for growth in OECD member states may be that they give lower priority to aid and higher priority to steps to deal with national problems. So far, however, there has been broad international agreement that aid commitments must be upheld during the economic downturn. Norway has a high international profile as a prime mover for more aid. The Government will ensure that Norway demonstrates solidarity with poor countries in the way that it deals with the financial crisis, so that we can play a leading role in promoting a similar approach internationally.

Figure 6.6 Official development assistance (ODA) from OECD countries, 2000–2007.

Source OECD, 2008

Countries that are not OECD members, such as China, India and a number of Arab countries, also provide aid. Although it is difficult to ascertain the exact amounts involved, there is little doubt that these countries are of considerable and growing importance. For example, aid from Saudi Arabia corresponded to around NOK 11 billion in 2007. China has pledged the equivalent of about NOK 100 billion to the African Development Bank, earmarked for trade and infrastructure projects. China has cancelled debt corresponding to more than NOK 7 billion from 21 African countries. Aid from India is estimated to be the equivalent of at least NOK 10 billion a year. So far, Bhutan and Nepal have been the largest recipients, but development cooperation with African countries is becoming increasingly important.

Many countries, including Norway, consider it important to develop new and innovative financing mechanisms to promote development and strengthen global public goods. Through active participation in international cooperation, Norway is taking part in the implementation of the Monterrey Consensus, which was adopted at the International Conference on Financing for Development in 2002. This is a UN-led process focusing on 1) mobilising developing countries’ own resources for development, 2) mobilising international resources: foreign direct investment and other private flows, 3) international trade as an engine for development, 4) increasing international financial and technical cooperation for development, 5) external debt and 6) reform of the international monetary, financial and trading systems. Progress in each of these areas and adaptation to new global challenges were discussed at the Doha Review Conference on Financing for Development in November–December 2008.

A number of new initiatives have been started as an extension of this cooperation. Long-term, binding commitments on support for the development of new vaccines and immunisation programmes have been converted to bonds, which can be sold on the international market. While aid donors will honour their commitments over a period of 5 to 20 years, revenues from the sale of «vaccine bonds» can be used immediately. Norway is one of the seven countries that have helped to develop this initiative. Norway is also involved in an initiative under which private companies that wish to develop and produce new vaccines for developing countries are given guarantees of future purchases at a fixed price. So far, guarantees worth more than NOK 8 billion have been provided. Certain countries have introduced an air passenger solidarity tax, which has so far provided the equivalent of about NOK 2 billion for purchases of medicines to fight HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis.

Funding of measures to address global climate and environmental problems is another important priority for Norway. The Clean Development Mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol plays a crucial role here. Norway is working towards further development of the CDM so that the poorest countries have more opportunity to take part.

Funding for women’s rights and gender equality

Women’s access to and control of financial resources is important for development. Education and paid employment have been an important basis for gender equality for Norwegian women. Financial independence is important both for women themselves and as a way of promoting gender equality within families. At the same time, women’s entry into the workforce over the last 30–40 years has been important for Norway’s economic growth and prosperity.

Norway has therefore given high priority to promoting women’s rights and gender equality as a cross-cutting issue in the negotiations on financing for development. This is not merely a question of aid, although Norway as a donor country does measure and monitor the proportion of aid funding used to promote women’s rights and gender equality. What is most important is that the developing countries understand the value of giving priority to women and gender equality in employment policy, trade and industry policy, and when developing services and welfare schemes. The administration of public funding in a way that promotes gender equality is one important approach. Many of Norway’s partner countries have already introduced initiatives to ensure that public funds are budgeted in a way that is more likely to promote gender equality. One important reason for the lack of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5 on improving maternal health is that services to protect women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights, such as qualified midwifery services and maternity clinics, are not given sufficient priority. These problems need to be addressed by reorganising priorities and addressing skewed power structures.

Textbox 6.1 Equal opportunities

«The greatest gains countries can achieve, economically as well as politically, come with empowering women, ensuring equal opportunity and health care, and increasing the ratio of women’s active participation in working life.»

Source Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg’s keynote address at the opening of the High-level Segment of ECOSOC, 3 July 2006

The Government will:

maintain the level of Norwegian aid so that it corresponds to at least one per cent of gross national income

take part in international cooperation on new and innovative financing mechanisms, focusing particularly on better regulation of international financial flows and measures to address global climate and environmental problems

work to improve understanding of the links between gender equality and economic growth, and of the need to manage public funding in a way that promotes gender equality.

6.4 Debt relief and responsible lending

During the past 10 years, the international community has cancelled a large proportion of the debts of the poorest and most heavily indebted countries. This is the result of two major international initiatives, the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC) and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI). However, much remains to be done, particularly for conflict-affected countries and post-conflict countries. One reason for this is that countries must provide guarantees that the funds released by debt relief are used for the benefit of the poorest groups. Debt relief alone is not enough. It must be accompanied by a policy to promote development.

In the wake of international debt operations, it is essential for both lenders and borrowers to behave responsibly. The growth in private and domestic debt and the emergence of new major lenders in Africa is changing the patterns of debt, and new challenges are arising. It is now essential to prevent a new debt crisis. The financial crisis is highlighting the need for guidelines on how development can be responsibly funded through loans.

An important task in the development of such guidelines is to agree on a definition of the concept of illegitimate debt. In the last few years, a number of civil society organisations that are working on debt issues have been calling for the concept to be expanded to include loans given to undemocratic regimes, debt related to purchases of weapons, and debt that is being repaid at the expense of basic human rights. On the other hand, there are creditors who see no reason to discuss illegitimate debt at all. This illustrates the differing views in the debate. Norway takes an intermediate standpoint. Our view is that earlier lending practice should be carefully considered so that good routines can be developed for the future. This will also provide a basis for evaluating whether old outstanding debt is legitimate. However, it will be necessary to agree on criteria that can be used in practice. The Government is maintaining a satisfactory dialogue and close contact with civil society on debt issues.

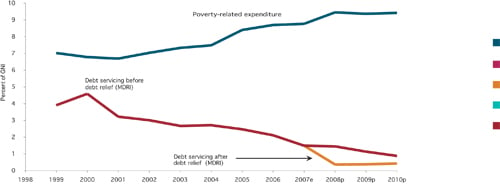

Figure 6.7 Debt servicing and poverty-related expenditure

Source World Bank, 2008

Norway has several times been one of the first countries to announce contributions to international debt operations. This has proved to have a positive effect on participation by other countries. One example is our contribution to efforts to prevent «vulture funds» from exploiting poor countries. Vulture funds are companies that buy up old debts at deep discounts and then require payment from the debtor based on the face value of the original debt instruments, plus interest. Vulture funds often target countries that will be eligible for international debt relief and that will afterwards be in a better position to repay old debts. Their put forward their claims through negotiations, litigation and the seizure of assets.

Through cooperation with the World Bank, Norway has contributed to the buy-back of commercial debt in Nicaragua. The agreement involved purchasing USD 1.3 billion of Nicaragua’s private debt for USD 64.4 million, and then cancelling the debt. Norway has also helped Zambia with investigation and legal counselling in connection with a lawsuit brought by the vulture fund Donegal International. The case was heard by the High Court in London. In a ground-breaking judgment, Donegal International’s claim for USD 55 million for a debt instrument for which it had paid only USD 3 million was ruled to be unreasonable. However, Zambia was held to be liable for part of the claim.

Norway is the largest donor to the Public Finance and Trade Programme run by the United Nations Institute for Training and Research, UNITAR, and plays a leading role in the international debate on debt management. Norway has also been involved in the preparation of principles and guidelines for sustainable lending by the OECD. China has also been invited to take part in this work, and is showing growing interest in cooperation.

In accordance with Norway’s policy, funding for debt cancellation for poor countries is allocated from outside the aid budget. Thus, this funding comes in addition to other aid. Norway is the only creditor country in the OECD that follows this principle, and this has elicited favourable responses from international organisations that are working on debt issues.

Textbox 6.2 Cancellation of debt from the Norwegian Ship Export Campaign (1976–80)

In 2007, the Government cancelled the remaining debts from the Norwegian ship export campaign of 1976–80. This campaign was a development policy failure. As creditor, Norway shares responsibility for the resulting debt. By cancelling the debts, Norway has taken responsibility, and Ecuador, Egypt, Jamaica and Peru do not have to pay back their outstanding debts.

The debts were cancelled unilaterally and unconditionally.

The Government will:

continue to pursue a progressive debt policy and take part in international debt operations

continue to uphold the principle that funding for debt relief is not to be allocated at the expense of the aid budget

work towards a new and more comprehensive mechanism for relieving the debt burdens of poor countries

pursue an active policy vis-à-vis international financial institutions and other creditors to ensure responsible lending.

6.5 International trade and development

The 2002 Conference on Financing for Development and the Doha Review Conference in November–December 2008 highlighted not only the need to increase transfers from rich to poor countries in the form of development assistance and debt relief, but also the need to mobilise private resources and foreign investment, and the importance of revenues from participation in international trade. The conferences also stressed that trade is an important engine for development.

Without revenues from export of its own goods and services, a country will not in the long term be able to import the goods and services needed for economic development and to improve the quality of life for its population. Division of labour and specialisation in the production of goods and services that can be sold at a profit are an important basis for economic growth. Nevertheless, greater participation in international trade and increased export revenues are not sufficient in themselves to ensure sustainable social and economic development. Trade is an important engine of development, but must form part of a broad-based, integrated national development strategy.

In a long-term development perspective, a general increase in production capacity, a more productive agricultural sector and a higher degree of processing, industrialisation, and better provision of services will be of crucial importance for the ability of developing countries to make use of trade as a means of development This is why international, regional and bilateral trade rules must ensure that developing countries have the market access and policy space they need to develop their production capacity and implement restructuring processes, such as those mentioned above, through an active industrial and employment policy.

For a growth in trade to lead to poverty reduction, the country concerned must also pursue an equitable national employment and distribution policy and take a responsible approach to environmental concerns. Increased exports and participation in international trade are therefore a necessary but by no means sufficient condition for development.

The World Trade Organization

The multilateral trading system in the World Trade Organization (WTO) provides an important framework for developing countries’ opportunities to benefit from participation in international trade. In principle, the WTO rules mean that all members are subject to the same rules and have the same rights, and thus give protection against arbitrariness and the abuse of power. However, this does not mean that prevailing power structures do not make themselves felt in the WTO. But power imbalances are counteracted by rules that all countries are bound by and by the fact that countries can strengthen their position through alliances and cooperation with other countries that are in the same situation.

Insufficient competence and capacity is a major problem for many poor developing countries, affecting their ability to take part in negotiations and other work in ordinary WTO bodies, and especially their ability to make full use of the WTO dispute settlement system. Various funds and mechanisms have therefore been established to promote competence and capacity building in developing countries, and the Advisory Centre on WTO Law (ACWL) has been set up to provide legal advice and support for developing countries in dispute settlement proceedings. Norway is one of the largest contributors to the ACWL and other multilateral competence-building mechanisms.

Textbox 6.3 The World Trade Organization

The WTO has three main functions: administering existing agreements, dispute settlement and acting as a forum for negotiations. On 1 January 2009, the WTO had 153 members.

The fundamental principles of all WTO rules are:

Most-favoured nation treatment – in other words, no discrimination, all countries must be treated equally

National treatment – no discrimination between domestic goods and firms and a country’s own citizens on the one hand and foreign goods, firms and citizens on the other

Binding commitments – member states cannot withdraw from their commitments other than through negotiations with the other members.

There may be several reasons why a country chooses to join the WTO and bind itself to following trade rules that limit national freedom of action:

the country’s economic policy becomes more stable and predictable, making it less risky for its own people and others to invest there

it can improve governance and strengthen institution-building in the country and make it more difficult for strong entities, whether multinationals or an elite within the country, to exploit weak institutions and political systems

it provides better and more predictable access to member countries’ markets, based on the principles of most-favoured nation treatment and national treatment

it ensures the right to take part in negotiations that affect market opportunities and the country’s freedom of action

it means that a country can make use of the WTO’s dispute settlement system if it is treated unreasonably by another country.

By becoming members of the WTO, countries agree to comply with the multilateral trade regime, which by definition limits national freedom of action. The benefits of participation in the international trading system must therefore be weighed against the freedom of action needed in national policy. On the other hand, the international trading system must take into account the very different situations of the member states.

The WTO rules already provide for a considerable degree of special treatment of developing countries. The scope of commitments in particular areas is different for developed and developing countries, and there are special rules for the least developed countries (LDCs) in a number of areas. However, it is important to continue the development of the multilateral trading system to include opportunities for accommodating developing countries.

The special situation and interests of the developing countries are the main focus of the current round of WTO negotiations, which began with the Ministerial Conference in Doha in 2001 and is therefore officially called the Doha Development Agenda. The aim is to help developing countries, including the poorest of them, to benefit from the welfare improvements and increase in prosperity that trade can provide, by enabling them to participate more fully in the multilateral trading system and the global economy. The Doha Ministerial Declaration particularly highlights the importance for developing countries of improved market access, balanced rules that give countries the necessary freedom of action to implement a development policy adapted to their own needs and stage of development, and technical assistance and capacity-building programmes.

The Government will, as a matter of priority, seek to ensure that the WTO negotiations result in a balanced agreement that also safeguards developing countries’ interests. Poor countries must not be deprived of the right to govern or the instruments that have been important for the development of our own nation into a welfare state, and the WTO rules must give developing countries sufficient freedom of action to pursue a policy suited to their own level of development and circumstances.

Regional and bilateral trade agreements

It is becoming increasingly common for developed and developing countries to conclude bilateral or regional trade agreements, or for developing countries to do so among themselves. Such agreements can be a supplement to the WTO system and encourage regional integration and boost trade.

However, in negotiations between rich and poor countries, or between countries from different categories of developing countries, the uneven distribution of power and negotiating capacity often represents a challenge. If the stronger party is able and willing to enforce its demands, there may be a greater risk that poor countries will be pressured into accepting agreements and conditions that they do not want.

If developing countries choose to conclude bilateral agreements, due regard should be paid to their level of development and need for political freedom of action.

Aid for trade

However, better market access and adjustments to the international trade regime are not enough. The poorest countries will often not be able to take advantage of an open, rule-based international trade regime without substantial and effective development assistance. Norway’s own experience shows that granting tariff-free access for imports from the least developed countries (LDCs) does not necessarily lead to a significant increase in imports. There may be various reasons for this, but a lack of production capacity and infrastructure, weak institutions and insufficient competence are serious barriers in many countries. Moreover, many poor countries find it very difficult to meet standards in areas such as food safety.

Textbox 6.4 Norwegian imports from developing countries

In addition to a number of special adjustments for developing countries, the WTO rules provide for special treatment to be given to developing countries through lower import tariffs (known as «preferences»). The Norwegian Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) and the arrangements for duty-free and quota-free access for imports of all goods from the least developed countries (LDCs) and from 14 low-income countries are key instruments for increasing imports of goods from developing countries.

The Norwegian market has a great deal of purchasing power. Increasing Norwegian imports from developing countries is one way of encouraging growth and fighting poverty in these countries. Norway’s imports from developing countries can be summarised as follows:

In 2007, imports from developing countries corresponded to about 13 per cent of total imports to Norway, and the total value was NOK 61 billion, a rise of 16 per cent from 2006.

The sharp growth in imports in recent years is to a large extent explained by a rise in imports from China. In 2007, goods to a total value of about NOK 28 billion were imported from China. This corresponds to about 6 per cent of Norway’s total imports.

Imports from LDCs totalled approximately NOK 1.8 billion in 2007, or 0.38 per cent of Norway’s total imports. However, almost the entire volume of imports from LDCs was from only four countries – Bangladesh, Cambodia, Equatorial Guinea and Liberia – and consisted mainly of clothing and textiles from the first two of these and oil and ships from the latter two. Thus, imports from the 46 other LDCs, including all of Norway’s partner countries in Africa, totalled about NOK 373 million, corresponding to only 0.07 per cent of Norway’s total imports.

Aid for trade is therefore an important focus area, and greater priority will be given to implementation of the Norwegian action plan Aid for Trade, which was launched in 2007. This focuses on three priority areas: good governance and the fight against corruption, regional trade, and women and trade. By giving higher priority to aid for trade, the Government wishes to help even the poorest countries to take advantage of opportunities to increase their export revenues. In the Government’s opinion, this will become increasingly important in the years ahead. Africa and the LDCs will be given priority in Norway’s aid related efforts to promote trade.

Trade barriers and the lack of effective infrastructure prevail at both national and regional levels. A special challenge for Aid for Trade is to promote regional integration and trade, especially in Africa. Regional cooperation is also necessary to meet the special challenges faced by landlocked countries. Sustainable trade development is conditional upon trade becoming more diversified, and upon breaking the uniform pattern of north-south trade. It is therefore essential to develop trade with neighbouring countries, but it is also important to further develop south-south trade across regional borders.

Trade, environment and development

Another issue being discussed in the WTO negotiations is liberalisation of trade in environmental goods and services. Such goods and services may for example be used to measure, prevent or limit environmental damage to air, water and soil, or may help to increase the production of renewable energy (examples are solar panels and wind turbines). By eliminating barriers to trade in environmental goods and services, it may be possible to speed up the transfer of environmentally friendly products, technology and production systems to developing countries. In addition, a number of developing countries can offer environmentally sound solutions, for example energy solutions, that are well adapted to the needs of many poor countries. Better access to environmentally sound, renewable forms of energy can be a means of reducing poverty and at the same time reducing impacts on the climate. However, in the WTO negotiations, agreement has not been reached on which goods and services are to be included here, and this is therefore a key topic of the negotiations. Norway is seeking to ensure that the negotiations apply to goods and services that give clear environmental benefits.

The Government considers that as a general rule, the multilateral trading rules and the multilateral environmental agreements should be mutually supportive. Norway is working actively within the WTO to ensure that this principle continues to be applied. It is also the Government’s policy to consider bilateral agreements and EFTA agreements in the context of cooperation on environmental issues and goals for sustainable development.

Sustained improvement of welfare requires a management regime for the environment and natural resources that is sound in ecological, social and economic terms. Rising production and a growth in exports can result in over-exploitation of natural resources. This is a particular problem in developing countries where there are weaknesses in governance and the legal system, and insufficient capacity to implement national environmental policy. Support for establishing and strengthening institutions and good governance is therefore also an important means of promoting sustainable social and economic development. Support for national implementation of the multilateral environmental agreements is an important contribution to the development of sound environmental and natural resource management. For example, the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety sets out a framework for biotechnology and the use of genetic resources, something that many developing countries need.

Trade and intellectual property rights

The WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (the TRIPS Agreement) is largely based on existing international conventions administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), a specialised agency of the UN. The TRIPS Agreement protects things such as patents, trademarks, and copyright against use or copying without permission. Patents are particularly important for products that are expensive to develop but easy to copy, such as pharmaceuticals.

The economic and social effects of patents have long been debated. In the absence of alternative products, the monopoly provided by the patent will generally result in higher prices for consumers. At the same time, the development of new products and production processes will benefit society. A fine balance is required to design rules that will protect immaterial property rights and at the same time not be an obstacle to research and development, and to ensure that incentives to develop knowledge do not result in a monopoly on knowledge. There has therefore been considerable debate on the TRIPS Agreement and its development impact in the broad sense, and particularly on its effects as regards public health, medicine, biodiversity and climate.

Negotiations are in progress within the framework of the Doha Development Agenda on amendments to the TRIPS Agreement. A large group of developing countries is calling for the agreement to be amended to harmonise more closely with the Convention on Biological Diversity and thus enable these countries to enjoy more of the benefits from the utilisation of their genetic resources. Norway has supported this initiative, and has proposed that it should be obligatory to disclose the origin of genetic resources that are used in a biotechnological invention. Norway is the first OECD country to support amendment of the TRIPS Agreement on this point, and the proposal was very well received by a number of developing countries in the Council for TRIPS. Norway has been a strong supporter of safeguarding opportunities to maintain local seed supplies by not setting too rigid requirements for plant variety protection, as well as of providing better and cheaper access to essential medicines.

The Government is also of the opinion that developing countries should not be pressured to accept provisions in bilateral or regional trade agreements under EFTA that restrict their freedom of action as regards patent protection, the protection of confidential test data and plant breeders’ rights.

The Government will:

contribute to a balanced new WTO agreement that gives developing countries better market access and freedom of action to pursue a national policy adapted to their level of development and circumstances

take developing countries’ level of development and need for political freedom of action into account in Norway’s trade agreements with developing countries, both bilaterally and through EFTA

assist developing countries to increase their exports by giving greater priority to the implementation of the Aid for Trade action plan

contribute to competence and capacity building that will improve the ability of developing countries to play an effective part in the WTO, among other things by making better use of its dispute settlement system

seek to ensure that the WTO negotiations on environmental goods and services result in both developmental and environmental benefits

seek to ensure that environment is included as a separate topic in negotiations with countries that play an important role in economic and environmental terms

seek to ensure that the principle that the multilateral trading rules and the multilateral environmental agreements should be mutually supportive is upheld in the WTO negotiations

work towards amendments to the TRIPS Agreement requiring disclosure of origin in patent applications, and flexible implementation of the provisions on plant breeders’ rights.

6.6 Private remittances from migrants

Figures from the World Bank show that legal flows of remittances sent by migrants from developing countries to their countries of origin total USD 200–300 billion per year. This is more than twice the total allocations of aid from OECD countries. Remittances to the very poorest countries total around USD 15 billion. There are wide variations between countries. In certain countries, remittances are extremely important, whereas in others remittance flows are very low. Remittance flows are also affected by developments in the world economy. Weaker global growth, which is now resulting in rising unemployment in many countries, may therefore have a major impact on remittance flows.

Remittances from migrants to poor countries can have positive effects at both micro- and macroeconomic level. Foreign currency can fund capital investments and other imports that promote development. At household level, remittances are an important source of income and lead to a rise in the standard of living. They can have a considerable poverty-reducing effect. Calculations show that access to this kind of extra income has reduced poverty in Uganda by 11 per cent. And it is estimated that on average, every Bangladeshi working abroad sends home remittances that lift one and a half more people above the poverty line – thus helping a total of seven million people.

Research also shows that remittances have other positive ripple effects, such as better access to services and more resources for education for members of the family. Girls in particular receive more schooling. On average, girls in families that receive remittances go to school for two years longer than other girls. This in turn reduces the scale of child labour. Remittances have more effect when male family members send the funds and the women of the family manage their use. Improving migrants’ opportunities to transfer money to their home countries is therefore an important development policy measure.

However, it is important to distinguish between aid, which is used to fund specific development goals, and private transfers, which do not necessarily benefit the most vulnerable groups in a country. Moreover, there are no international systems to ensure that the poor countries, where under-employment is most prevalent, are given first priority when it comes to access to the international labour market. The distributional effects of remittances are thus highly variable both within and between countries, particularly in comparison with aid.

Members of the immigrant community in Norway already send large sums of money to families in their countries of origin. Transaction costs are relatively high in Norway. A report drawn up by the International Peace Research Institute in 2007 shows that large sums, up to 20 per cent, are absorbed by middlemen.

Facilitating cheaper, more efficient and more transparent transfer mechanisms is important in both humanitarian and development terms. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has therefore initiated a dialogue with relevant authorities and the financial sector to find good ways of doing this. The Ministry is supporting a pilot project for improving the website Finansportalen.no. This is intended to promote competition between actors involved in transfers of money to developing countries.

Cheaper and more effective transfers through legal channels are a means of reducing the scale of informal and illegal forms of money transfers. In areas where infrastructure is poorly developed, such as Somalia and the Kurdish areas in northern Iraq, it is almost impossible to transfer money through official channels. People are therefore dependent on informal channels. The Government will continue the dialogue on money transfers with the financial sector in developing countries, with immigrant groups in Norway, and with the authorities in their countries of origin. The aim is to simplify and lower the cost of such transfers, while at the same time maintaining the necessary controls, as discussed in the white paper on labour immigration (Report No. 18 (2007–2008) to the Storting) and the subsequent recommendation of the Standing Committee on Local Government and Public Administration.

So far, there have been no applications for licences under the current rules to broker cross-border payments using informal channels such as the Hawala system. Licensing requirements, inspection and enforcement systems, and measures to combat money laundering for legal cross-border payment services are intended to ensure confidence in such systems and to prevent tax evasion and possible financing of terrorism. Adjustments to these rules to increase the proportion of cross-border money transfers that are made through formal, legal mechanisms to countries where financial services are poorly developed are currently being considered. Any changes will be considered in the context of implementation of the EU Payment Services Directive, which will enter into force on 1 November 2009. The directive sets out minimum requirements for cross-border payment service providers and provides for less strict requirements for smaller enterprises. The Government will consider whether it would be appropriate to make use of these provisions to facilitate the establishment of legitimate services targeted specially towards migrants in Norway.

The Government will:

continue its dialogue with relevant actors in Norway and in countries that are major recipients of remittances, in order to facilitate more transparent and effective systems for money transfers

upgrade the website Finansportalen.no to make it easier to make cross-border money transfers, focusing particularly on developing countries.