1 Introduction

World poverty is no coincidence. It is a result of international power structures. Of poor policies and poor leadership. Of historical trends and conflicts. Of oppression and discrimination. Although the world’s rich and poor are becoming increasingly intertwined in a complex global economy, the goods remain unevenly distributed. The disparity between those who have most and those who have least has never been greater.

International human rights form the normative basis for Norway’s development policy. This policy aims to assist states in fulfilling their obligations and enable individuals to claim their rights. The white paper On equal terms: Women’s rights and gender equality in development policy (Report No. 11 (2007–2008) to the Storting) was an important step forward in Norway’s systematic efforts to address the need for change in power structures at all levels. The perspectives in that white paper and the subsequent recommendation of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs are to be taken into consideration in all aspects of Norwegian development policy.

Norway’s efforts to promote international development are based on the principle of solidarity. There is broad support for our development policy and the aid we provide among the Norwegian public and in the Storting. The government budget for 2009 represents a milestone in this respect: we will spend 1 per cent of gross national income (GNI) on development in poor countries. In addition, Norwegian NGOs raise funds totalling several hundred million kroner.

Through its development policy, Norway influences factors that promote or impede development. Aid is one important development policy tool. Norway has already initiated targeted efforts in key areas such as good governance, human rights, education, health, and gender equality. The results of Norwegian aid have been good. However, the Government believes that the results of both its overall development policy and its specific aid efforts could be even better with a more strategic approach.

Addressing climate change, resolving violent conflicts and improving the management of financial flows will be of crucial importance for the future of developing countries. Here Norway has the opportunity to take responsibility at the international level. We can make a difference. The Government believes that the time is ripe for a stronger policy for addressing climate change, conflict and capital flight in a development policy perspective.

Climate change is already high on the international agenda. Scientific research leaves no doubt about the reality of man-made climate change and the seriousness of the situation. Changes to our living conditions will spin out of control. We will be fighting a losing battle against poverty. At the same time, there is broad popular support across national borders for measures to address climate change. Politicians all over the world are facing demands for action. This raises the hope that new political approaches and technological innovation can alleviate the situation and create new opportunities for growth, especially in developing countries. We must make use of this room for action, and put efforts to stabilise the global climate system at the centre of development policy.

Most of today’s violent conflicts are in poor, fragile states. Conflict exacerbates poverty and reverses development. Several of these conflicts have spillover effects far beyond the areas directly involved, and are attracting widespread international attention. Peace needs to be firmly rooted in the population, and negotiations must be followed up with tangible improvements to living conditions. Norway has a long tradition of contributing to peacebuilding. We also have credibility as a development actor. This gives us opportunities to pursue a policy that highlights the links between security and development.

Globalisation brings a number of advantages, but it also creates challenges. For example, it has become far easier to move capital from one country to another. This means that it is relatively simple to transfer large sums of money out of poor countries and into what are known as secrecy jurisdictions or tax havens. Substantial amounts are lost through corruption. Opportunities to make huge profits very fast are resulting in overexploitation of developing countries’ natural resources. Globalisation also leads to increased migration. Migrants send large sums of money to their families in their countries of origin. Other forms of capital are also transferred to developing countries, for example through grants, loans and investments from growing economies such as China and India.

The Government considers it important to ensure that developing countries are given greater access to global capital and better opportunities for value creation. We believe it is important to pursue an active policy that steers financial flows in a more development-friendly direction and stops illegal capital flight out of poor countries. This is particularly important now that the financial crisis is undermining the economic forces for development: trade and investment are falling and less priority is being given to aid.

In order to further strengthen its strategic approach to development, the Government will focus its efforts on areas where Norway has recognised expertise, and where Norwegian efforts are in demand and can give added value for the partner country concerned. It is by combining Norwegian know-how and political will that we have the best prospects of success. In recent years, we have achieved the best results when we have made optimal use of our international engagement and the full breadth of our foreign policy and development policy apparatus to promote bold, innovative political initiatives. The debt relief campaigns and the fight against landmines and cluster munitions are good examples of the contribution Norway can make by combining political courage with the resources and expertise needed to succeed.

Closer links between development policy and foreign policy

This white paper represents a step forward in the process of integrating development policy and foreign policy. Our development policy involves us in processes and funding mechanisms that have a place within a wider political framework. Both giving and receiving reflect political priorities. This means that some of the themes dealt with in this white paper will also be discussed in the forthcoming white paper on our foreign policy priorities. Work on the two white papers has been closely coordinated so that they complement each other while at the same time functioning as independent documents.

The central aim of our foreign policy is to safeguard Norwegian interests. In development policy, the focus is on poor countries’ interests. However, these interests coincide in many areas. Climate policy is one. A stable climate is in everyone’s interests; it is a global public good. Climate change concerns people all over the world. Although rich and poor countries are being affected differently, we have a common interest in gaining control over climate change. Here, our mutual dependence across national borders is clearly apparent. Human rights is another area of common interest that Norway promotes through both foreign and development policy. In the long term, a stable international legal order – which is in Norway’s interests – can only be developed by countries that respect fundamental human rights. But there are other policy areas where the interests of poor and rich countries are in direct opposition to each other. Certain issues relating to migration and trade are examples here.

An approach that includes an emphasis on common interests can further enhance understanding of and support for an active foreign and development policy, and can open up opportunities for new forms of cooperation. The Government believes that it is important for development policy to promote global public goods. However, the focus on safeguarding common interests and seeking to strengthen global public goods does not mean that the Government wishes to use development policy to further Norwegian economic interests or any other form of Norwegian self-interest. The objective of Norway’s development policy is to reduce poverty and promote human rights.

The road leading to this white paper

It is now about five years since the Storting debated the previous white paper on development policy, Fighting Poverty Together(Report No. 35 (2003–2004) to the Storting). The subsequent recommendation of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs showed that there is broad agreement on the main lines of our development policy. This white paper raises two key questions: What are the consequences of the developments in international politics over the last few years for our development policy? And how can we further improve our development results?

This white paper uses the term aid to refer to the funding of the various measures that donor and recipient have agreed to give priority to. Aid can be given in many ways and through many different channels. In contrast to other factors that govern how a country develops, aid is a tool over which both donor and recipient have a considerable degree of control. Development policy encompasses the full range of political approaches and tools that Norway uses actively to influence the various factors that determine the framework for development in poor countries. The initiatives we take and the messages we communicate in various international contexts are important development policy tools. So is an awareness of the consequences of our foreign policy for conditions for development in poor countries. Aid is, of course, a key development policy tool, but it is only one of several.

In this white paper, we present our understanding of changes in the framework for development, and how these create opportunities for a strategic and future-oriented development policy. Our objective has been to produce a document that is to the point and provides the Storting with a good basis for discussing strategic development policy measures. This white paper stakes out the course for Norwegian development policy. It takes a general approach. Practical tools for implementation will be developed, as appropriate, at a later stage.

This white paper takes into account dialogue in and with the Storting in connection with the annual budget proposals, foreign policy addresses in 2006 and 2007, and the recommendation of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs on certain development policy issues dealt with in the Minister of the Environment and International Development’s address to the Storting on 8 June 2007. It also refers to the Government’s status report on Norway’s efforts in relation to the UN Millennium Development Goals in the 2009 budget proposal.

In 2006, the Government appointed the Norwegian Policy Coherence Commission to examine the practical political opportunities for achieving greater policy coherence in relation to international development. The committee has drawn up an Official Norwegian Report (NOU 2008:14), which examines Norwegian policy in a number of different areas, including trade, investment, financing for development, climate and energy, migration, transfer of knowledge and technology, and peace, security and defence. The report, together with responses from the public hearing on the report, forms part of the background material for this white paper.

During the preparation of this white paper, we have maintained close dialogue with relevant organisations and institutions in Norway. We have received important input from a number of different Norwegian actors, including NGOs and research institutions. Progress on the white paper has been presented in many different contexts both at political level and in the international development community. Information has also been published on the Government’s website (www.regjeringen.no), where an electronic mailbox has been available for the public to post their points of view. This has been widely used. Many of the suggestions have been taken into account in the white paper.

1.1 The backdrop: A changing world

In the 1980s, the more prosperous part of the world was divided into two economic and political blocs. It was a bipolar world, with the US and NATO on one side, and the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact on the other. The balance of terror between these blocs was the predominant factor in security policy. The EU had 12 member countries. Germany was divided in two. Saddam Hussein was an important Western ally in the Iran–Iraq conflict. The poorest countries were referred to as the Third World and found themselves caught between the two blocs. At the same time, the balance of terror extended beyond the two blocs and the two superpowers had allies all over the world.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, there was a period of just under ten years when the US was the dominant political and economic power. During this period, the world was more or less unipolar. Gradually, however, the US position has been challenged – both politically and economically. Today, the EU has 27 member countries, including several former Warsaw Pact members. Security policy is again at the top of the international political agenda. Twenty years ago, who would have guessed that the most important security policy engagement for NATO and for Norway would be in Afghanistan?

Textbox 1.1 The US – prepared to take the lead

«Finally, we will make it clear to the world that America is ready to lead. To protect our climate and our collective security, we must call together a truly global coalition. I’ve made it clear that we will act, but so too must the world.»

Source Remarks by the President on Jobs, Energy Independence, and Climate Change, East Room of the White House, 26 January 2009

The US economy is now under severe pressure. Nevertheless, the country is expected to retain its position as the most important superpower for the foreseeable future. And the new US administration has announced that it will pursue an active and inclusive foreign policy

The financial crisis and its rapid spin-off effects demonstrate how closely interwoven the international economy has become. In order to maximise profitability, the production of goods and services is being transferred across national borders – particularly to developing countries, where labour is cheap. Transfer of production leads to transfer of capital and knowledge. The internationalisation of business is a major factor for development in many poor countries, although the very poorest countries are only able to attract foreign investment to a limited extent.

Figure 2-1.EPS China is playing an increasingly important role as a development partner in a number of African countries.

Source Photo: Christopher Herwig/Scanpix

The trend towards internationalisation has been underway for several decades, but it has only recently become obvious that we are in the midst of a shift in political and economic power – from west to east. China has experienced extraordinary economic growth. Never have so many people been lifted out of poverty as in China in recent years. However, the financial crisis is making itself strongly felt in the country. At the beginning of 2009, unemployment had already increased by several million. The full extent to which the financial crisis will affect China’s development is uncertain. We should bear in mind that it is the country with the largest population in the world, and a growing proportion of its population is completing higher education.

China’ economic growth is also evident in its more active engagement in the global arena. China is Africa’s third largest trading partner after the US and France. A number of countries are refinancing their loans through loan and trade agreements with China. For the first time in the World Bank’s history, African countries have being paying back their loans ahead of schedule. China is outcompeting the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) by offering loans and agreements with few requirements regarding reform, good governance or respect for human rights. China is also investing heavily in several mineral- and oil-producing countries in Africa and the Middle East. Many countries welcome China’s engagement, partly as a counterweight to years of American and European domination, but also as an important player at the international level and in connection with its own poverty reduction. China regularly invites African heads of state to conferences, where investment and trade agreements worth huge sums of money are concluded.

Following Beijing’s example, India held its first meeting for African leaders in 2008. Strong economic growth has increased the country’s self confidence in the international arena. It has been both able and willing to criticise the existing international framework on several occasions, for example during the World Trade Organization (WTO) negotiations. For many years, India has been running its own development programme, and is now the leading actor in the region. It is not possible, for example, to envisage a resolution to the conflict in Sri Lanka without India playing a key role as facilitator, or without at least the approval of New Delhi.

South Africa is playing a crucial role in sub-Saharan Africa. It holds the key to stability in Zimbabwe, and this in turn will be decisive for development in the region. The extent to which South Africa succeeds in this role will be a test of Africa’s credibility internationally as a continent that takes the responsibility for its own development. In Latin America, it is Brazil that is the economic engine – the driving force for regional integration in vital areas such as infrastructure, energy supply, economic development and security. And China is in a class of its own. Together with Russia, these countries are known as the BRICS countries, after the first letter of their names. Other countries with growing economies and ambitions are also playing an important part in the international arena.

Although the growing economies are by no means a homogenous group, they do have similar interests in many areas. Their ambition is clear: they want to play a more prominent role in the major political forums. We have moved from a unipolar to a multipolar world.

The traditional major powers are responding to this trend. Several countries are now advocating that the rapidly growing economies should be given a more prominent role in key international organisations. At the G8 meeting in 2008, the need to include China and India to create a G10 was discussed. The Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund has stated that the Fund will be unable to retain its legitimacy unless rights and obligations are redistributed to reflect the economic balance of power in the world today. The G20, which was established to ensure cooperation on major challenges created for example by the financial crisis and weaker global growth, is the first forum where established and emerging economic major powers meet on an equal footing.

From a development point of view, it is interesting to note that forums that used to focus on economic and security policy issues have become central arenas for discussing the challenges faced by developing countries. This applies to the G8, within NATO and not least in the WTO.

1.2 Development and the fight against poverty

Development is a complex concept. Over the years, there has been a growing emphasis on considering development in a broader perspective, and not in terms of economic growth alone.

A common departure point is to view development within a framework of opportunities, capabilities and liberties. Development gives people the opportunity to live longer and healthier lives, access to knowledge, better standards of living and living conditions, and greater opportunity to participate in society and in decision-making processes that affect them.

It is this understanding of development that forms the basis for the Millennium Declaration, which won unanimous support at the UN General Assembly in 2000. These countries reaffirmed their determination to ensure:

that basic needs for education, food, health and housing are met

sustainable economic development that reduces social disparity and poverty

the rule of law, participation in society, freedom, democratic governance and equality

opportunities to retain cultural identity

environmental, economic and social sustainability

human security in the face of threats such as hunger, unemployment and conflict.

The deadline for achieving the Millennium Development Goals is 2015. They represent the first universally recognised agenda for development. They set clear targets and indicators for the most urgent development needs. These goals form an important basis for Norway’s development policy, and we have taken on a particular responsibility for MDGs 4 and 5 on reducing child mortality and improving maternal health.

Development policy should seek to provide a national and international framework that enables individuals to create a better future for themselves, and enables poor countries to do likewise. A key element is control – at individual, social and state level. It is important to create a situation where people can control their own resources and claim their rights, where they enjoy a minimum of economic and human security, and are thus able to make choices that will improve their future.

Major differences

The approximately 150 countries and territories that are on the list of recipients of official development assistance (ODA) approved by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have very different starting points for development. The OECD’s list of ODA recipients includes both the world’s poorest countries, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Haiti, as well as upper middle-income countries such as Argentina and Croatia. The middle-income country Botswana has a far greater capacity for making use of development aid than its neighbour Zambia, which is defined as a least developed country (LDC). Major emerging economies such as China and India are also included on the list, and are thus defined as developing countries.

The debate on development will lose both nuance and relevance if we make sweeping generalisations about such a broad range of countries. It is vital that we recognise that developing countries make up a large and diverse group. The results achieved in the fight against poverty are very uneven – both within countries and between countries. In Asia, prosperity has increased significantly. Whether or not this trend can be maintained in the years ahead remains to be seen. High food and energy prices combined with poor prospects for growth in the world economy will create considerable difficulties.

Despite the fact that several countries in sub-Saharan Africa are enjoying steady economic growth, the effect on poverty in the region as a whole has so far been limited. One reason for this is that many of these countries had such weak economies at the outset that their capacity for translating economic growth into immediate poverty reduction has been very limited.

The impact of the global financial crisis will vary from country to country. The emerging economies are being drawn headlong into the crisis, but are in a stronger position to deal with it than the poorest countries, where it may have far-reaching impacts. In the short term, poverty must be expected to increase.

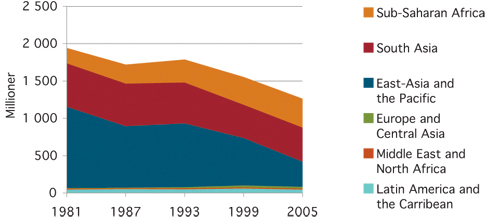

Figure 1.2 Number of people living in extreme poverty 1981–2005.

Source Chen and Ravallion, Policy Research Working Paper 4703, World Bank, 2008

Poverty affects different social groups differently. Women account for a larger proportion of the world’s poorest than men. Single women are hit hardest of all. One woman dies every minute from complications associated with pregnancy or childbirth, adding up to half a million women each year. Some 40 million people have fled from wars and conflicts. More than 30 million people are infected with HIV. Most of these live in sub-Saharan Africa. Children are affected by poverty in different ways to adults, and they are especially vulnerable to hunger and disease.

1.3 Norway’s development policy profile

Norway is one of the world’s richest countries. Eurostat’s figures for 2008 show that Norway’s per capita gross national income (GNI) is more than 80 per cent higher than the EU average and some 55 per cent higher than in Sweden and Denmark. This entails obligations.

Norway’s development policy is based on values such as solidarity, compassion and human rights, and on a fundamental conviction that all people are entitled to a life of dignity. Many Norwegians are actively engaged in development efforts, for example through religious groups, various interest organisations and the labour movement. We can use our privileged economic situation both to maintain development aid at a level of at least one per cent of GNI, and to take new initiatives in international arenas to address the major challenges the world is facing. This Government intends to follow up its political message with concrete aid efforts.

Norway is a major energy producer. We have rich natural resources. We have 100 years’ experience of renewable energy production and 40 years’ experience of oil and gas production. We have developed a comprehensive system for sound management of our resources that takes full account of health, safety and environment issues in addition to economic and energy policy interests.

As a producer and net exporter, Norway is helping to meet the world’s demand for energy, which is a key factor for economic growth and social development. Norway intends to play an active role in the development of new renewable energy sources that can replace today’s fossil energy carriers. We can provide experience of hydropower that will be useful as the world seeks to shift to cleaner sources of energy. Norway’s technical and administrative expertise from the petroleum sector can also play a part in efforts to address climate and energy issues. The Government is actively seeking to ensure coherence between development and foreign policy objectives and environment and energy policy efforts.

The Government will use various approaches to address the problem of climate change. We are giving priority to decarbonisation of fossil fuels, and are intensifying efforts to develop and share clean energy technology and to stop deforestation. A change in pace is needed in these areas at global level if we are to successfully come to grips with climate change. They will become increasingly important areas of Norwegian policy. In this way, we can safeguard Norway’s interests and at the same time take a responsible approach in the global efforts to address climate change.

The Nobel Peace Prize and the legacy of Fridtjof Nansen have helped to give Norway a reputation as a pioneer in peace efforts. This image has been reinforced by our participation in a number of peace and reconciliation operations and engagements. Norway has never been a colonial power. This creates opportunities for engagement that are closed to former colonial powers. In certain situations, our position as a modern European country that is not formally connected to the EU bloc can also open up opportunities. In 2008, the Washington-based think tank Center for Global Development ranked Norway in first place among OECD members in the Security component in its Commitment to Development Index. This shows that we have a good starting point for maintaining a high level of engagement in peace and reconciliation efforts.

Norway is one of the largest contributors to the UN and a champion of a UN-led world order. Global governance based on national sovereignty and respect for human rights is of vital importance both for developing countries and for ourselves. Our position in the UN and other multilateral organisations means that we can play an active role in both supporting and advocating reform initiatives.

Norwegian society is based on a model that ensures that the population’s basic needs are met. Our welfare model is one of the reasons for Norway’s good international reputation. Although the solutions we have devised cannot be transferred directly to other countries where circumstances are different, we have valuable experience to share in our dialogues with the authorities in developing countries. This includes experience of developing a welfare policy in times of economic hardship.

The five main axes of our development policy are as follows:

Our development policy is designed to strengthen the position of the poor

Norwegian development policy is designed to challenge the unequal distribution of power within and between countries. We must support national development plans and an international framework that will facilitate economic and social development in poor countries.

Norway’s development policy is intended to help countries with the process of meeting the basic needs of as many people as possible within a system that safeguards and promotes individuals’ rights. We will mainstream women’s rights and equality throughout our development policy efforts. It is also vital to ensure economic growth in order to maintain the present trend of global poverty reduction. Our focus on steering international financial flows in a development-friendly direction will help to increase global capacity for funding the fight against poverty. Growth makes it possible for countries to pursue an active distribution policy, for example by providing better social services and a safety net for vulnerable groups.

A rights-based development policy has a strong normative effect. Active use of human rights as a framework for development cooperation will raise awareness among both governments and the general population. The result will be stronger local ownership and greater sustainability. The implementation of the human rights conventions is therefore an objective in itself, as well as being an important tool that should be integrated into all development efforts.

Our development policy is designed to promote sustainable development

Norwegian development policy is designed to promote sustainable development. Our development policy should be part of the solution to the serious environmental problems of climate change and loss of biological diversity, and not part of the problem. At the same time, our contributions to global environmental policy must also play a role in the fight against poverty. This integrated approach to environment and development is an important tool in efforts to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), improve the health and living conditions of the poor, and meet global challenges relating to natural resources and the environment.

Our development policy is designed to safeguard global public goods and strengthen global rules

The framework for development is increasingly affected by global conditions. The UN has concluded that we will not be able to achieve the MDGs unless we gain control of climate change. Nor can we expect to see development in countries that are ravaged by conflict or epidemics. Such problems may start in individual countries, but cannot be resolved without a broad international effort. In many areas there is strong interdependence, and it is clear that we have a common destiny. A broader and more holistic approach to development policy makes it necessary to identify the links between national and global problems, and how interests may extend beyond national borders. This is of crucial importance not only in order to improve the situation of the poor, but also to safeguard our own interests, and not least the interests of future generations.

The international norms that safeguard individuals’ rights and provide rules governing relations between countries are key global public goods. An operational and effective UN that successfully mobilises the political will and resources needed to solve global challenges is essential if these norms are to be really effective.

Through its development policy, Norway will also promote the implementation of international agreements in developing countries and seek to ensure that their authorities incorporate globally agreed policies into national legislation. All UN Member States have taken on legal obligations to implement one or more international agreements on human rights.

Our development policy and our domestic policies should be seen in relation to each other

Norway’s overall impact on the development framework for poor countries is result of our policies in a number of different areas. Unless we take account of the effects of our actions in all policy areas – including the decisions that we help to make in international organisations and forums – we risk undermining our ability to reduce poverty through aid and other means. The Norwegian Policy Coherence Commission’s report, Coherent for Development? (NOU 2008:14) highlights a number of areas where there is room for a more development-friendly balance between national and development policy interests.

Our development policy focuses on areas where Norway has particular expertise

Our efforts will be concentrated to a greater extent on areas where Norwegian expertise is in demand and provides added value for partner countries. The prospects for success are greatest where we also have a strong political engagement. The Government has identified the following sectors where Norway is considered to have particular expertise and where we should focus our efforts: climate change, environment, sustainable development, peacebuilding, human rights, humanitarian assistance, oil and clean energy, women and gender equality, good governance and the fight against corruption.

1.4 Local ownership and the Norwegian agenda – conflicting perspectives?

All countries are responsible for their own development. All countries make choices and set priorities on the basis of their political system, power structure, values and available resources. This is true for Norway, and it is true for poor countries. We should not underestimate the forces, including a country’s history and background, that influence choices of policy and direction. Nor should we underestimate how difficult it is for one country to intervene in the processes that guide political choices in another country.

The effects of donor countries’ development policies and of international aid depend significantly on the efforts of the political leadership, the public and private sectors and civil society in recipient countries. These efforts help to determine the room for action for Norway’s development efforts. And this is how it should be. National ownership of both development processes and individual projects is essential. Without this, development will not be sustainable. National ownership must be understood in a broad sense. It does not only apply to a country’s government and parliament, but also to civil society and the full range of institutions that help to ensure a balanced power structure.

Norway attaches importance to implementing the objectives of the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness at both international and national level. This means that Norway’s development cooperation work will be guided by the principles of national ownership, alignment with recipient countries’ systems, harmonisation among donors, results-based management and mutual accountability. In order to enable recipient countries to take responsibility themselves, the conditions and mechanisms involved must allow a long-term approach and the elbow room needed to be able to make independent decisions. Increased use of budget support on the basis of national development plans together with better financial management make it possible to achieve a clearer division of roles.

Human rights are under pressure in both rich and poor countries. In 2008, the US think tank Freedom House reported the first signs since 1994 that democratic values are on the wane. Authoritarian forms of government are winning ground. Amnesty International has documented serious human rights violations in the majority of the countries in the world. Sadly, there is a wide gap between the obligations undertaken by the majority of countries and the realities on the ground in many of them.

Textbox 1.2 Lesbian and gay rights in developing countries

All the countries of the world have committed themselves to protecting human rights on a non-discriminatory basis. Neither culture, religion nor tradition can justify violations of human rights. Human rights apply to all individuals regardless of gender, race, religion or sexual identity. We cannot ignore systematic abuse and discrimination of sexual minorities.

Norway will therefore be a fearless champion of equality. This includes fighting against discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation, which affects gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people. This will require broad, clearly targeted measures in sensitive areas. We will speak out where others find it easier to remain silent.

Organisations that represent minorities can provide useful guidance for the kinds of measures that are best suited to local conditions.

Norway’s credibility as a champion of human rights depends on us being consistent in our efforts to fight discrimination and promote minority rights.

Figure 1.3 In 2006, South Africa’s Parliament passed the Civil Union Act, entitling same-sex couples to marry on an equal basis with heterosexuals.

Source Photo: Dennis Farrell/Scanpix

The disparity between our commitment to universal rights and the varying importance other countries attach to these rights is apparent in many development policy areas. The white paper On equal terms: Women’s rights and gender equality in development policy states clearly that Norway will speak out boldly and clearly, even on the most sensitive issues. However, it also points out that we must accept the fact that promoting gender equality is a long process that frequently challenges powerful cultural and religious forces. Our rights-based approach must always be based on sound knowledge of the global situation and access to expertise on the particular situation in each partner country. We must identify and support relevant agents of change and tailor our approach and efforts to local conditions.

Despite the dilemmas that can arise, our approach towards countries where there are human rights challenges is to seek access and dialogue. We will use the opportunities our development policy provides for promoting human rights. Our strategy in this difficult terrain must be to defend and promote principles that are universal. We will use all the channels offered by the open and interdependent world community to exert an influence.

1.5 Administrative and financial consequences

The close links between foreign policy and development policy are already taken into account in the Government’s organisation of work in these areas. In 2004, the administrative responsibility for embassies with development responsibility was transferred from Norad (Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation) to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. At the same time, responsibility for policy-making, strategy formulation and information activities, as well as country-specific and regional expertise, was integrated into the Ministry. More funding and more authority were delegated to the embassies. Norad was designated as the centre of technical expertise for the whole Norwegian development apparatus, with responsibility for providing advice, for quality assurance, and for channelling long-term aid through NGOs. This reorganisation has made it easier to ensure coherence between long-term development cooperation, humanitarian assistance and bilateral and multilateral aid. Overall, making the Ministry of Foreign Affairs responsible for the administration of all development policy tools has led to closer integration and coordination between foreign and development policy. At a practical level, significant effort has gone into improving the administration of grants. New guidelines have been drawn up, and a central support function has been established with overall responsibility for ensuring uniform practice in the Ministry.

Many of the measures put forward in this white paper involve a change of policy that will have few budgetary consequences. Other measures are based on priorities set out in budget proposals in recent years, such as increasing support for countries in conflict. A closer focus on fragile states will mean that additional support is channelled to these countries. The Government’s efforts to address international financial flows will primarily be of a strategic, political nature and will not require high levels of funding. Provision has already been made in the budget for climate-related measures, primarily under item 166.73 (climate change and deforestation). Right from the start, the intention has been to provide fresh funding for these activities. The Government attaches great importance to women’s rights and gender equality. A separate budget item, 168.70 (women and gender equality), was established in 2007.

This white paper proposes more strategic use of the different aid channels, so that bilateral aid is linked more closely to areas where Norway has expertise that is in demand, while funding for sectors such as health and education will primarily be via multilateral channels. Programme category 0310 (bilateral assistance) for 2008 contains an item for each region, but not for individual countries, with the exception of Afghanistan. The measures proposed in this white paper will be implemented within existing budgetary frameworks. This means that the objectives, actions and priorities set out in this white paper will be followed up through the ordinary budget proposals in line with normal practice.