2 Scope and development of the State’s direct ownership

Table 2.1 presents an overview of the companies discussed in the report. These companies primarily consist of all the commercial companies, together with the largest companies with sectoral policy objectives. The companies concerned are the same as those covered annually in the Norwegian State ownership report.

Tabell 2.1 The companies discussed in the report

Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs | Shareholding | Ministry of Trade and Industry | Shareholding | |

Eksportutvalget for fisk AS | 100% | Aker Holding AS | 30% | |

Nofima AS | 56.8% | Argentum Fondsinvesteringer AS | 100% | |

Bjørnøen AS | 100% | |||

Ministry of Health and Care Services | Shareholding | Cermaq ASA | 43.5% | |

AS Vinmonopolet | 100% | DnB NOR ASA | 34% | |

Helse Midt-Norge RHF | 100% | Eksportfinans ASA | 15% | |

Helse Nord RHF | 100% | Electronic Chart Centre AS | 100% | |

Helse Vest RHF | 100% | Entra Eiendom AS | 100% | |

Helse Sør-Øst RHF | 100% | Flytoget AS | 100% | |

Norwegian Center for Informatics in Health and Social Care (KITH)1 | 70% | Innovation Norway | 51% | |

Norsk Helsenett SF | 100% | Kings Bay AS | 100% | |

Kongsberg Gruppen ASA | 50% | |||

Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development | Shareholding | Mesta AS | 100% | |

Kommunalbanken AS | 100% | Nammo AS | 50% | |

Norsk Hydro ASA | 34.3% | |||

Ministry of Culture | Shareholding | Norsk Eiendomsinformasjon AS | 100% | |

Norsk Rikskringkasting AS | 100% | SA AB | 14.3% | |

Norsk Tipping AS | 100% | Secora AS | 100% | |

SIVA SF | 100% | |||

Ministry of Education and Research | Shareholding | Statkraft SF | 100% | |

Norsk Samfunnsvitenskaplig Datatjeneste AS | 100% | Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani AS | 99.9% | |

Simula Research Laboratory AS | 100% | Telenor ASA | 54% | |

Uninett AS | 100% | Yara International ASA | 36.2% | |

University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS) | 100% | |||

Ministry of Petroleum and Energy | Shareholding | |||

Ministry of Agriculture and Food | Shareholding | Gassco AS | 100% | |

Statskog SF | 100% | Gassnova SF | 100% | |

Veterinærmedisinsk Oppdragssenter AS | 39.9% | Petoro AS | 100% | |

Enova SF | 100% | |||

Ministry of Transport and Communications | Shareholding | Statnett SF | 100% | |

Avinor AS | 100% | Statoil ASA | 67% | |

BaneTele AS | 100% | |||

NSB AS | 100% | Ministry of Foreign Affairs | Shareholding | |

Posten Norge AS | 100% | Norfund | 100% |

1 The Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion also owns a 10.5% shareholding in KITH AS.

2.1 Scope

2.1.1 The State’s various ownership in companies

The State also has investments in companies in Norway and abroad beyond the direct ownership covered in this report. The most important institutions and administrative environments for the State’s asset investments in companies are Norges Bank (Government Pension Fund Global (SPU)), the National Insurance Scheme Fund (Government Pension Fund Norway (SPN)) and the Government Bond Fund) and the direct State ownership administered by the various government ministries. The policy discussed in this report only applies to the direct State ownership.

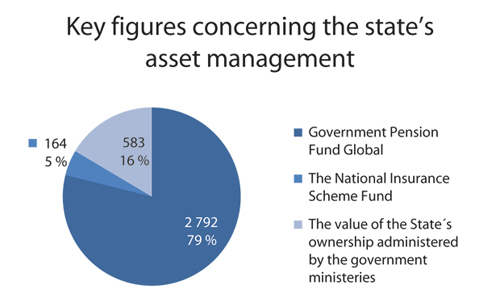

Figur 2.1 Key figures concerning the State’s asset management as of 30 June 2010. NOK billion and per cent.

Kilde: The Government Pension Fund Global, the National Insurance Scheme Fund and the Ministry of Trade and Industry

As shown in Figure 2.1, the ownership administered through the Government Pension Fund Global (SPU) and the Government Pension Fund Norway (SPN) represents almost 85% of the State’s ownership in companies, whilst the direct ownership that is administered by the government ministries accounts for the remainder.

The reasons behind the State’s investments through SPU and SPN, and the direct ownership administered by the government ministries differ considerably. These forms of ownership have different goals and different State institutions administer the ownership. The State’s investments through SPU are financial investments administered by Norges Bank as part of the administration of Norway’s petroleum assets. These investments are limited to foreign companies and the maximum shareholding in a company is 10 per cent. Investments through SPN are also financially motivated and are administered by the National Insurance Scheme Fund. SPN is subject to restrictions which require it to invest in the Nordic region and not to have shareholdings in excess of 15 per cent in any company in Norway or in excess of 5 per cent in any company in the Nordic region.

The State’s direct ownership which is administered by the government ministries largely comprises strategic holdings in Norwegian companies. These holdings are not administered from a financial portfolio perspective, but from a strategic and industrial perspective in commercial companies and on the basis of sectoral policy goals for other companies. The ownership varies from major shareholdings in many of the company’s largest listed companies, through fund-based companies such as Argentum Fondsinvesteringer AS and Investinor AS1, wholly owned infrastructure companies with sectoral policy objectives and virtual monopolies such as Avinor AS and Statnett SF, to smaller sectoral policy companies with a special remit such as Kings Bay AS and Norsk Samfunnsvitenskapelig Datatjeneste AS (NSD).

Ownership in Norwegian industry today

Little research has been carried out recently into the scope of the State ownership viewed in the context of the private sector ownership in Norway. Only a few of the limited companies in Norway are listed on Oslo Stock Exchange. Most analyses that have been carried out only cover the listed companies. However, a recently published book entitled “Eieren, styret og ledelsen. Corporate Governance i Norge”2 analyses around 94,000 Norwegian limited companies. The book notes that three-quarters of the assets and around 90 per cent of the jobs in the limited companies covered by the survey are in companies that are not listed on the stock exchange. Two-thirds of the companies analysed are owned by families with a shareholding of more than 50 per cent.

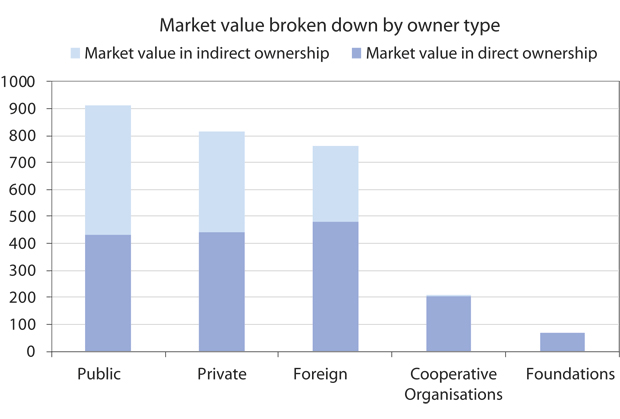

There are no recent figures for the total value creation within Norwegian industry broken down according to ownership. Figures from 20033 estimate the value of companies in Norwegian industry to be NOK 2,700 billion. Of this, the State’s ownership accounted for approximately 33 per cent, while privately owned companies accounted for 30 per cent. The rest of industry was owned by foreign capital (28 per cent), cooperative organisations (7 per cent) and foundations (2 per cent).

Figur 2.2 Ownership of Norwegian industry broken down by owner type (NOK billion).

Kilde: Erik W. Jakobsen, Leo Grünfeld: Hvem eier Norge? Eierskap og verdiskaping i et grenseløst næringsliv, Universitetsforlaget 2003.

Figures for shareholdings on Oslo Stock Exchange indicate a transition from public ownership to foreign ownership during the period 2003 to 2010. During the period from the end of 2003 to the end of 2010, public sector owners and companies reduced their shareholdings on the stock exchange from 42 per cent to 35 per cent, whilst the proportion of foreign owners increased from 28 per cent to 35 per cent. Other owner groups have collectively remained at around 30 per cent. The public sector, including State-owned companies, is one of the largest owner groups in Norwegian industry. The State’s ownership is particularly visible in the listed companies in which the State’s shareholdings (including minor holdings owned by local authorities and State companies) accounted for 35.3 per cent of the equity instruments on Oslo Stock Exchange at the end of 2010. As the above estimates show, there is also widespread private sector ownership in Norway which plays a key role in the growth of Norwegian industry and value creation.

2.1.2 Historical overview of the State’s direct ownership

Since the end of the Second World War, the State has had substantial direct ownership in Norwegian companies. The reasons behind the State ownership in Norwegian companies have varied as society and the political landscape has changed. A common thread in the State ownership has often been the desire to safeguard certain social or political considerations. Within this framework, certain companies have often been State-owned as a result of time-specific assessments and decisions linked to the individual companies concerned.

For a certain period of time after the Second World War, access to capital from abroad was limited, partly as a result of capital restrictions between countries. A limited private capital market in Norway and a political desire to bring about industrial growth led the State to contribute long-term capital with the aim of encouraging industrial development. The role of the State in the industrial recovery that has taken place since the Second World War must be viewed in light of this. The State’s involvement in companies such as Årdal og Sunndal Verk (1947), Olivin4 (1948) and Norsk Jernverk (1955) was justified through the failure of the capital market with regard to new developments and risk investments.

When the production of oil and gas began in the 1970s, the desire for a stronger stake in the extraction of natural resources lay behind the State’s ownership of Statoil and its decision to increase its holding in Norsk Hydro. Subsequently, Petoro AS was also established in order to administer the State’s direct financial interest in the petroleum sector, whilst Gassco AS was established to act as operator for gas pipelines and transport-related gas processing facilities.

During the banking crisis in the 1990s, the State’s take-over of shares in many banks was essential in order to avoid the bankruptcy of socially critical financial institutions. Most of these were subsequently privatised by being sold off, but the State has retained a shareholding of 34 per cent in DnB NOR ASA.

A political desire to promote national industrial growth and safeguard enterprises that were considered to be of strategic importance has resulted in substantial State involvement within widely differing enterprises. Security and contingency considerations lay behind the State’s involvement in Raufoss Ammunisjonsfabrikker (later Raufoss ASA, which in 1998 divested the ammunition operation and formed the Nordic ammunition group Nammo), Kongsberg Våpenfabrikk (wound up in 1987, except for the company’s defence operation, which was continued and is now part of the Kongsberg Gruppen) and Horten Verft (composition with creditors 1987). Norsk Jernverk (converted in 1988) and Norsk Koksverk (closed down in 1988) are further examples of a desire to build up national industry.

The relationship to the State of enterprises has also changed over time, partly in that State administrative enterprises have been set up as independent companies and adapted to markets with competition. This has manifested itself in the divestment of State agencies to companies. Important company formations include the conversion of Televerket to Telenor AS in 1994 and the creation of the State enterprises Statkraft and Statnett in 1992. Other examples of such company formations are Flytoget AS divested from NSB, Entra Eiendom AS divested from Statsbygg, Cermaq ASA against the background of the State’s grain business, the conversion of the administrative company Postverket into the current Posten Norge AS, Mesta Konsern AS5 divested from the National Public Roads Administration and Secora AS6 divested from the National Coastal Administration.

In many cases, the State has chosen to become a stakeholder in enterprises for sectoral policy reasons. This is one of the reasons behind the State take-over of the hospitals. The aim is to lay the foundations for the holistic management of the specialist health service, partly through the establishment of a clear statutory State responsibility. The State ownership in this field is also intended to facilitate more efficient utilisation of the resources that are allocated to the sector, thereby ensuring the provision of better health services to the population.

The discussion above illustrates that the State’s direct ownership during the post-war period has been linked to various objectives and needs relating to social and political development.

2.1.3 The scope of the State’s direct ownership

As mentioned above, the State’s ownership that is administered by the government ministries largely comprises strategic shareholdings that are not administered on the basis of a financial portfolio perspective, but from a strategic and industrial perspective in the case of commercial companies and from a sectoral policy perspective as regards other companies. The ownership varies from major shareholdings in many of the country’s largest listed companies to wholly owned companies with a purely sectoral policy remit. In terms of company law, these enterprises are organised as limited companies, public limited companies, State companies, healthcare enterprises and other types of company founded under a particular act of legislature. Every year, the State’s ownership report is published. This report presents an overview of the State’s direct ownership which is administered by the government ministries7.

The State has different objectives behind its ownership of the various companies. To clarify the objectives behind the State’s shareholding in each of the companies, in the 2006 State’s ownership report, the government placed all the companies in one of four categories, a categorisation which is also used here:

Companies with commercial objectives

Companies with commercial objectives and national anchoring of their head office

Companies with commercial and other specifically defined objectives

Companies with sectoral policy objectives

Administration of the companies with commercial objectives (Categories 1–3)

One of the key aims behind the State management of the companies in Categories 1–3 is to maximise the value of the State’s shares and to contribute to the positive industrial development of the companies. In addition, the State’s ownership of some of these companies has other primary aims, such as national anchoring of the head office or certain other specific objectives.

As part of the professionalization of the execution of State ownership, there has been a conscious strategy to ensure that the administration of the companies for which one of the primary objectives behind the State ownership is commercial operation, is generally handled by the Ownership Department of the Ministry of Trade and Industry.

At the end of 2010, the Ministry of Trade and Industry, via the Ownership Department, administered the State’s shareholdings in a total of 21 companies8. The other companies where administration of the State’s ownership has been transferred to the Ministry of Trade and Industry, via the Ownership Department, are Secora AS (2008, from the Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs) and Norsk Eiendomsinformasjon AS (2010, from the Ministry of Justice and the Police). Administration of the shareholdings in these companies was transferred as the companies had progressed a long way in their development as commercial enterprises and the State no longer had any sectoral policy objectives behind its ownership.

The State shareholdings in the other companies for which one of the primary objectives is commercial operation are administered by the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development (Kommunalbanken AS), the Ministry of Agriculture and Food (Veterinærmedisinsk Oppdragssenter AS), the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (Statoil ASA) and the Ministry of Transport (Baneservice AS, NSB AS and Posten Norge AS).

In terms of their value, the State’s shareholdings in the listed public limited companies Statoil ASA, Telenor ASA, Norsk Hydro ASA, Yara International ASA, Kongsberg Gruppen ASA, Cermaq ASA, DnB NOR ASA and SAS AB represent a substantial part of this group of commercially oriented companies. The State’s shares in these companies collectively had a value of around NOK 504 billion at the end of 2010. Of the unlisted companies in Categories 1–3, Statkraft SF is the most valuable company. Today, the company is one of Norway’s largest companies measured in terms of value.

Administration of the companies with sectoral policy objectives (Category 4)

The sectoral policy companies are companies with a State shareholding which have sectoral policy and social objectives, where the primary goals of the State ownership are non-commercial. These companies are administered by the various government ministries which are responsible for sector policy in the different areas. For example, the State holdings in Statnett SF and Statskog SF are administered by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy and the Ministry of Agriculture and Food respectively. Examples of the objectives behind the State ownership in the sectoral policy companies are to own, manage and develop a nationwide network of airports (Avinor AS), to limit the availability of alcoholic beverages (AS Vinmonopolet) and to provide good and uniform specialist healthcare services to anyone who needs them (the regional healthcare enterprises).

Although the sectoral policy companies do not primarily have commercial objectives, financial results and efficient resource use are nevertheless pivotal considerations for these companies. The financial results of these companies must be balanced against sectoral policy goals. As owner, the State aims to achieve the relevant sectoral policy and social goals as resource-efficiently as possible.

The degree of commercial orientation varies between the sectoral policy companies. For example, NRK AS operates in markets that are exposed to competition, whilst AS Vinmonopolet administers a monopoly.

In terms of size, the regional healthcare enterprises are dominant amongst the non-commercial enterprises. These healthcare enterprises employ around 110,000 people and receive over NOK 100 billion in income per year.

2.2 Developments linked to the State’s direct ownership since 2006

2.2.1 Transactions and changes in the State’s ownership

Mergers

In December 2006, the boards of Statoil ASA and Norsk Hydro ASA announced that they had agreed to recommend the merger of Norsk Hydro’s petroleum business and Statoil ASA. Behind the merger lay a desire to establish a strong international player with solid technological expertise. The government presented the matter to the Parliament in Bill to the Storting no. 60 (2006–2007). The Parliament adopted the recommendations in June 2007 and gave the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy and the Ministry of Trade and Industry a mandate to vote for the transactions at the companies’ extraordinary general meetings, which were held on 5 July 2007. The merger was implemented with effect from 1 October 2007. Following the merger, the State owned 62.5 per cent of the shares in the new company StatoilHydro ASA. The State purchased shares in StatoilHydro ASA on the market during the period 2 June 2008 to 5 March 2009, and has owned 67 per cent of the company since then. In total, shares worth around NOK 19.3 billion were acquired. The company was renamed Statoil ASA in 2009.

Nofima AS was founded on 1 January 2008 through the merger of the former Akvaforsk AS, Fiskeriforskning AS, Matforsk AS and Norconserv AS; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 69 (2006–2007). The State owns 56.8 per cent of the merged company.

Sale of shares

After SIVA SF sold its 49 per cent shareholding in Veterinærmedisinsk Oppdragssenter AS (VESO AS) to Aquanova Invest AS, the State decided to give the new owners the option to acquire a majority shareholding in the company. This was done in order to enable VESO to take advantage of opportunities for industrial growth in the future. A private placement was therefore carried out, which resulted in Aquanova Invest AS’ shareholding reaching 60.1 per cent; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 22 (2008–2009). As a result of a previous agreement, the State’s shareholding in 2010 was reduced to 34 per cent.

In November 2008, the State exercised its right to sell its remaining 50 per cent shareholding in BaneTele AS to the Broadband Alliance; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 35 (2008–2009).

In 2010, the State’s 53.4 per cent shareholding in ITAS amb AS was transferred to Industri Lambertseter AS; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 20 (2005–2006).

Share purchases

In 2007, the State entered into an agreement with Aker ASA, Investor AB and SAAB AB concerning a joint shareholding in Aker Solutions ASA through Aker Holding AS; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 88 (2006–2007). The State’s share of the stake in Aker Holding AS is 30 per cent. Aker Holding’s only business is to own shares in Aker Solutions ASA. The aim behind the purchase was to secure a long-term strategic ownership in the technology and industrial group Aker Solutions ASA.

After Kommunekreditt was acquired by KLP in the spring of 2009, it was considered appropriate for the State to acquire KLP’s share of 20 per cent in Kommunalbanken AS; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 79 (2008–2009). The State, via the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development, carried out the purchase of the shares in June 2009 at a price of NOK 531 million. As a result, Kommunalbanken AS became wholly owned by the State.

Owner transactions linked to the companies’ buy-back of their own shares are discussed in section 5.4.1.

Equity expansions

Norfund is financed by capital grants via the State budget, and the fund’s equity has been strengthened through annual contributions via the State budget during the period 1997–2011. In total, Norfund’s equity has been boosted by around NOK 6.3 billion during this period.

In 2007 and 2008, Kommunalbanken AS received equity totalling NOK 100 million because the bank had experienced strong lending growth for a number of years and its tier one capital adequacy ratio had therefore decreased. If its equity had not been strengthened, Kommunalbanken would have been forced to reduce its lending growth.

At the beginning of 2009, a share capital expansion of NOK 1.2 billion was carried out by Eksportfinans ASA, in which the State participated on a pro rata bases with its holding of 15 per cent and subscribed to shares equivalent to NOK 180 million; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 33 (2007–2008). This came about as a result of the turbulence in the international capital markets, which caused Eksportfinans to suffer an unrealised price loss in the securities portfolio.

In February 2009, SAS AB presented its new strategy, Core SAS. This new strategy involved the strengthening of the company’s capital situation, and in April 2009, a share capital expansion of approximately SEK 6 billion was carried out in SAS AB. The State participated on a pro rata basis with its holding of 14.3 per cent and subscribed to new shares equivalent to NOK 709 million. The matter was considered by the Parliament on 12 March 2009; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 41 (2008–2009). As an extension of its new strategy, Core SAS, the board of SAS AB proposed a further share capital expansion in the company in February 2010. The board also decided to ask the general meeting for a mandate to take out a convertible bond loan of up to SEK 2 billion. The State participated in the capital expansion on a pro rata basis with its holding of 14.3 per cent, subscribed to new shares equivalent to NOK 583 million and supported the proposal to give the board a mandate to take up a convertible bond loan; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 79 (2009–2010) and Bill to the Storting no. 89 (2009–2010). The board issued a convertible bond loan in April 2010 of SEK 1.6 billion. If the loan were to be converted to shares in its entirety, which cannot be done until 2015, the Norwegian State’s holding could be reduced by around 1.5 per cent, and the total State holding (Sweden, Denmark and Norway) could be reduced from 50 per cent to 45 per cent.

In the spring of 2009, Argentum Fondsinvesteringer AS received NOK 2 billion in new equity for investments in private equity funds; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 37 (2008–2009). This represented one of a number of initiatives launched by the government in connection with the international financial crisis.

In accordance with the proposal from the board of DnB NOR ASA, in autumn 2009 the company carried out a share capital expansion of NOK 13.9 billion through a guaranteed rights issue. The State participated on a pro rata basis with its holding of 34 per cent and subscribed to shares equivalent to NOK 4.7 billion. The matter was considered by the Parliament on 17 November 2009; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 22 (2009–2010).

In June 2010, the State participated in the amount of NOK 4.4 billion in a share capital expansion carried out by Norsk Hydro ASA in connection with the acquisition of Vale S.A.’s aluminium operation; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 131 (2009–2010). In connection with the transaction, a private placement aimed at Vale S.A. was also approved, which resulted in the dilution of the State’s holding as set out in Bill to the Storting no. 131 (2009–2010). As a result of the implementation of the take-over as of 28 February 2011, the State’s holding was reduced to 34.26 per cent. The government aims to increase its holding up towards 40 per cent. The transaction alters Norsk Hydro’s strategic position and gives the company the raw material-based resource base that appears necessary in order to take an active role in the rapidly growing aluminium industry.

In connection with the re-balancing of the State budget for 2010, the equity in Statkraft SF was increased by NOK 14 billion; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 24 (2010–2011). The strengthening of the capital situation provides a robust financial basis on which the company can continue its offensive initiative within environmentally friendly renewable energy in the future, both in Norway and internationally.

Reorganisation at group level

Mesta Konsern AS was founded on 21 May 2008 as part of the demerger of Mesta AS. The operation was organised into the parent company Mesta Konsern AS and eight subsidiaries. The new corporate structure was introduced on 1 September 2008.

New establishments

Gassnova SF was established by a Royal Decree of 29 June 2007. Ownership was assigned to the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. Prior to this, Gassnova was an administrative body.

In the State budget for 2008, the government proposed the establishment of a new State investment company with equity of NOK 2.2 billion. Statens Investeringsselskap AS was founded on 21 February 2008 as a subsidiary of Innovation Norway. The company has since been renamed Investinor AS.

Norsk Helsenett SF was founded on 1 June 2009, with ownership being assigned to the Ministry of Health and Care Services; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 67 (2008–2009). Later the same year, the company took over the entire operation of Norsk Helsenett AS and associated rights and obligations. Until then, Norsk Helsenett AS had been owned by the four regional healthcare enterprises.

Winding-up proceedings

In June 2007, the Parliament decided to wind up Statskonsult AS. From 1 January 2008, a new administrative body, the Agency for Public Management and eGovernment, was established, consisting of employees of Statkonsult AS, Norge.no and the Norwegian e-Procurement Secretariat. This formed part of an initiative to strengthen the work relating to renewal, ICT, management, organisation and reorganisation, information policy, procurement policy and competence development.

At the ordinary general meeting of Venturefondet AS in April 2007, it was decided to reduce the company’s equity by NOK 75 million. This reduction in capital formed part of the strategy to wind up the company; cf. Recommendation to the Storting no. 163 (2006–2007). At the ordinary general meeting on 16 April 2009, it was decided to dissolve Venturefondet AS; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 1 and Recommendation to the Storting no. 5 (2010–2011). All items in the company's portfolio have now been wound up.

Other ownership

Raufoss ASA was delisted from Oslo Stock Exchange in spring 2004 and it was decided to wind up the company in the same year. Before the decision was made to wind up the company, all existing fixed assets were sold to industrial owners, who have largely continued Raufoss’s operations. Raufoss ASA is still in the process of being wound up.

Report to the Storting no. 46 (2003–2004), Om SIVAs framtidige virksomhet, proposed an increase of NOK 150 million in SIVA’s equity over the course of a few years, to be repaid to the public purse; cf. Recommendation to the Storting no. 30 (2004–2005). In line with this, the conversion of NOK 50 million from debt to the public purse to invested capital was carried out in 2005, 2006 and 2007.

Eksportutvalget for fisk AS (EFF) was converted to a limited company as of 1 September 2005. EFF is the joint marketing organisation for the fisheries and aquaculture industry. Operation of the company is fully financed by the fisheries and aquaculture industry through a marketing fee, pursuant to the Act on export duty on fish products.

In June 2007, Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani AS received NOK 250 million in the form of a subordinated loan. The loan was linked to the consequences of the fire in the Svea Nord mine in 2005 and the clarification of the associated insurance settlement; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 69. The loan has since been repaid; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 29 (2006–2007).

In 2008, a mandate was granted for the State to participate in the amount of NOK 750 million in a portfolio guarantee agreement for Eksportfinans ASA; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 62 (2007–2008). A majority of the shareholders decided to participate in this agreement in order to protect the company from further falls in the value of the securities portfolio.

The State undertook to provide a loan on market conditions to Eksportfinans ASA until 31 December 2010; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 32 (2008–2009). This was linked to the challenges that the company was facing in gaining access to long-term financing due to the financial crisis. Access to the loan was granted in order to ensure that Norwegian export companies could continue to receive offers concerning the financing of export contracts which qualify for State-supported loans from Eksportfinans.

In 2009, NOK 150 million was awarded to Avinor AS as part of a package of initiatives; cf. Bill to the Storting no. 91 (2008–2009). This package of initiatives involved State support, zero dividends and deferred repayment for State loans in order to help the company make the necessary security investments. In order to contribute further to this, the one-off award of a NOK 50 million State loan with deferred repayment and zero dividends was granted; cf. Bill 1 S (2009–2010).

In May 2007, in connection with the consideration of Report to the Storting no. 12 (2006–2007) Regionale fortrinn – regional framtid, the Parliament gave its approval of the government’s proposal to split the ownership of Innovation Norway between the State and the county councils; cf. Recommendation to the Storting no. 166 (2006–2007). The necessary statutory amendments were sanctioned in January 2009. The change in ownership was implemented with effect from 1 January 2010; cf. Bill to the Odelsting no. 10 and Recommendation to the Odelsting no. 30 (2008–2009). Prior to this change, Innovation Norway was wholly owned by the State.

On 4 June 2010, Mesta Konsern AS repaid NOK 129 million to the State as a result of a ruling by EFTA’s Monitoring Body that the company had received funds in breach of the regulations concerning State aid.

Reorganisation within the regional healthcare enterprises

In January 2007, the government decided to merge the former healthcare regions Helse Sør and Helse Øst: cf. Bill to the Storting no. 44 and Recommendation to the Storting no. 167 (2006–2007). The reason behind the decision was the need to improve the utilisation of resources and the coordination of the specialist healthcare service between the two health regions, particularly in the region of the capital. The new regional healthcare enterprise Helse Sør-Øst RHF was established with effect from 1 June 2007.

2.2.2 Return on investment and development in the value of the State’s portfolio since the previous ownership report

Listed companies

Tabell 2.2 Overview of the development of the value of the State’s holdings in listed companies 31.12.05–31.12.10 (NOK million).

Company | State shareholding 31.12.10 | Value of State’s shareholding 31.12.05 | Value of State’s shareholding 31.12.10 | Increase in value for State | Realised for State during the period1 | Accumulated dividend to State during the period2 | Net growth in value for State during the period3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cermaq ASA | 43.54% | 2 205 | 3 624 | 1 419 | - | 397 | 1 817 |

DnB NOR ASA | 34,00% | 32 727 | 45 356 | 12 629 | 108 | 6 417 | 19 154 |

Kongsberg Gruppen ASA | 50.00% | 1 860 | 7 980 | 6 120 | – | 348 | 6 468 |

Norsk Hydro ASA4 | 43.82% | 78 644 | 30 205 | -48 439 | -992 | 8 315 | -41 116 |

SA AB | 14.29% | 2 045 | 917 | -1 129 | -1 294 | – | -2 423 |

Statoil ASA | 67.00% | 238 035 | 296 104 | 58 069 | -16 857 | 71 712 | 112 925 |

Telenor ASA | 53.97% | 61 013 | 84 816 | 23 803 | 2 113 | 9 429 | 35 345 |

Yara International ASA | 36.21% | 11 198 | 35 299 | 24 101 | 1 101 | 1 910 | 27 112 |

Total for listed companies | 427 727 | 504 301 | 76 574 | -15 821 | 98 529 | 159 282 |

1 Total from the purchase/sale of shares, capital invested and/or settlements for deleted shares for the State.

2 Including dividend provision for the State for the 2009 accounting year, paid in 2010.

3 Including changes in shareholdings.

4 The value line for Norsk Hydro ASA 2010 was calculated using the number of shares that applied after the rights issue.

The value of the State’s assets on Oslo Stock Exchange directly administered by the government ministries at the end of 2010 was NOK 504 billion and compares with NOK 428 billion at the end of 2005, representing an increase of NOK 76 billion during the period; cf. Table 2.29. During the same period, the State received NOK 98.5 billion in dividends from the listed companies, in addition to NOK 15.8 billion net invested in the form of the purchase/sale of shares, capital invested and/or settlements for deleted shares for the State10. Collectively, this gives a return on the State’s combined portfolio of 37.2 per cent, equivalent to an average annual return of 6.5 per cent.11 The return on the State’s portfolio has therefore been higher than on the main Oslo Stock Exchange index, which by 32.2 per cent during the same period rose, corresponding to an average annual return of 5.7 per cent.

Figur 2.3 The value of the State’s shares in Yara International ASA increased by 315 per cent during the period 2005–2010.

Kilde: Yara International ASA and Sebastian Braum

Other companies with commercial objectives

Table 2.3 presents a selection of other companies with commercial aims, as well as some of the largest companies with sectoral policy objectives. These companies are not valued on the capital market. For the sake of simplicity, the valuation estimates for the companies were determined using the company’s book equity minus minority interests12.

The State’s total assets in these companies amounted to NOK 87.2 billion as of 30 June 2010, compared with NOK 60.7 billion as of 31 December 2005. During the same period, the State received NOK 36.3 billion in dividends from these companies, as well as NOK 7.4 billion net invested in the form of the purchase/sale of shares, capital invested and/or settlements for deleted shares. In total, this gives a return of 91.3 per cent based on accounting sizes, corresponding to an average annual return of 13.9 per cent.

Tabell 2.3 Overview of developments in the value of the State’s holdings in selected non-listed companies 31.12.05–30.06.10 (NOK million).

Company | State shareholding 30.06.10 | Value of State’s shareholding 31.12.05 | Value of State’s shareholding 30.06.10 | Increase in value for State | Realised for State during the period1 | Accumulated dividend to State during the period2 | Net growth in value for State during the period3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Aker Holding AS4 | 30% | – | 1 006 | 1 006 | -4 819 | 238 | -3 575 |

Argentum Fondsinvesteringer AS | 100% | 3 080 | 5 679 | 2 599 | -2 000 | 384 | 983 |

Baneservice AS4 | 100% | 163 | 164 | 1 | – | 27 | 28 |

BaneTele AS5 | 0% | 131 | – | -131 | 715 | – | 584 |

Eksportfinans ASA | 15% | 387 | 733 | 346 | -180 | 155 | 321 |

Electronic Chart Centre AS | 100% | 12 | 19 | 7 | – | 4 | 11 |

Entra Eiendom AS | 100% | 7 170 | 6 518 | -652 | – | 519 | -133 |

Flytoget AS | 100% | 734 | 969 | 235 | – | 269 | 504 |

Kommunalbanken AS6 | 100% | 809 | 3 925 | 3 116 | -963 | 302 | 2 455 |

Mesta AS | 100% | 2 252 | 1 341 | -911 | 129 | 77 | -705 |

Nammo AS | 100% | 306 | 1 435 | 1 129 | -62 | 282 | 1 349 |

NSB AS4 | 100% | 6 176 | 6 572 | 396 | – | 1 214 | 1 610 |

Posten Norge AS | 100% | 4 739 | 5 819 | 1 080 | – | 1 085 | 2 165 |

Secora AS | 100% | 52 | 61 | 9 | – | 2 | 11 |

Statkraft SF | 100% | 34 061 | 51 524 | 17 463 | – | 31 326 | 48 789 |

Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani AS | 100% | 518 | 1 434 | 916 | -329 | 385 | 972 |

Venturefondet AS7 | 0% | 96 | – | -96 | 100 | – | 4 |

Veterinærmedisinsk Oppdragssenter AS4 | 40% | 18 | 7 | -11 | – | 12 | 1 |

Total non-listed companies | 60 704 | 87 205 | 26 501 | -7 410 | 36 281 | 55 372 |

1 Total from the purchase/sale of shares, capital invested and/or settlements for deleted shares for the State.

2 Including dividend provision for the State for the 2009 accounting year, paid in 2010.

3 Including changes in shareholdings.

4 Aker Holding AS, Baneservice AS, NSB AS and Veterinærmedisinsk Oppdragssenter AS do not compile half-yearly figures. The value as of 31 December 2009 was therefore used.

5 In autumn 2006, a private placement of NOK 625 million was carried out, which gave the Broadband Alliance a 50 per cent holding in BaneTele AS. In November 2008, the State exercised its right to sell the remainder of the company to the Broadband Alliance.

6 After Kommunekreditt had been acquired by KLP in spring 2009, the State, via the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development, acquired KLP’s 20 per cent share in Kommunalbanken. As of 26 June 2009, Kommunalbanken AS was wholly owned by the State.

7 The aim behind the State’s ownership of Venturefondet in recent years has been to wind up the fund. In connection with this, NOK 75 million was reversed in 2007 through a capital reduction, whilst in 2010, a wind-up dividend of NOK 24.7 million was paid.

2.2.3 Developments in industry and within ownership administration

The discussion in this section is particularly linked to the holdings in the commercial companies. For companies that have largely sectoral policy objectives, an inter-ministerial working group has been set up to look in more detail at governance forms with regard to these companies. This work is expected to be completed in 2011.

The State has traditionally been the owner of Norwegian companies which have operated in Norway and where the companies’ strategic, financial and industrial development within the framework of the objectives established by the State for its ownership has been in focus.

In recent years, many of the companies with commercial objectives have become more international in their operations as a result of increasingly global trading patterns and an ever-increasing pace of technological and industrial development. Examples of problems that have attracted attention in the wake of these developments are principles for corporate governance, coporate social responsibility and pay and incentive schemes. A common characteristic of these problems is that they are considered to be important to the financial development of the companies in both the short and the long term, and as such they represent a development where owners have gained a broader perspective on what contributes to the industrial and financial development of the companies.

This is not a new development since the previous ownership report was presented in 2006, but the pace of change has accelerated in recent years and influenced the way in which owners, including the State, manage their ownership.

On behalf of the Ministry of Trade and Industry, the consultancy firm McKinsey & Co has prepared a report on the general characteristics of international developments within corporate governance for both State and private players, as a starting point for the further development of the State’s owner follow-up13.The report highlights key, global development characteristics:

A faster pace of development within industry in the form of technological development and internationalisation is making it more demanding for both owners and boards to contribute to value creation for their company. More frequent changes and more demanding requirements for reorganisation necessitate an active owner which supports the company’s development by being able to take fast decisions. It is becoming increasingly important for an owner to have a dynamic perspective on value development within each individual company. Owners must define how they wish to create value in their role as owner. This requires the considerable input of resources, partly to secure an adequate level of knowledge concerning each individual company in the portfolio and the market in which it operates.

An increase in the number of passive institutional owners with a small shareholding in a large number of companies has resulted in many companies being seen as “owner-less”. This creates scope for and expectations concerning active ownership from major owners, regardless of whether they are in the State or the private sector. An important implication for a State owner with a substantial shareholding is that, in addition to developing its own strategic analysis for each company and using this analysis in its dialogue with the company, it must ensure competent and effective boards through a professional process for evaluation and selection.

Since the Enron and WorldCom scandals, amongst others, there has been a focus on the important of correct corporate governance. The weaknesses in this area, which were once again demonstrated during the financial crisis, reinforced this focus further. Companies with management or owners which the market believes do not meet the requirements for good corporate governance are penalised in the market and have their value reduced. To safeguard the legitimacy of State ownership, it is vital that the State ownership fulfils generally accepted requirements for good corporate governance and that the ownership is organised in a way which clearly separates the role of owner from the State’s other roles with respect to the companies it owns. There must also be complete transparency surrounding the objectives behind the State ownership.

Each of these points is discussed in more detail below. A discussion is also presented of the way in which different types of owner seek to maximise the development of their companies. This presentation is based on McKinsey’s report.

2.2.3.1 Faster global industrial and technological development

Faster global changes as regards technology and innovation are reducing expectations as regards the lifetime of companies and making it more difficult for companies to maintain strategic positions over time. Companies must change rapidly. A strong position today is less of a guarantee of a strong position tomorrow than it used to be.

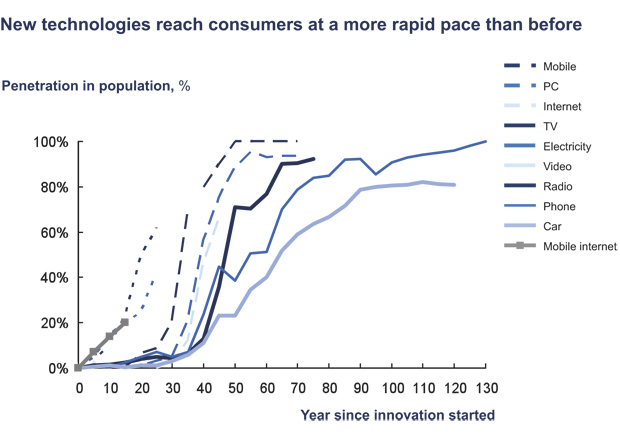

New technology is winning market share at an ever-increasing pace. While it took about 60 years from the launch of the telephone until 60 per cent penetration was achieved amongst possible users, and almost 130 years until 100 per cent penetration, the mobile telephone took just 25 years to reach a similar level of penetration; cf. figure 2.4, which shows how much faster new technology reaches consumers today.

Figur 2.4 New technology – penetration amongst the population per year after the innovation was launched (per cent).

Kilde: Corporate Angels, http://www.corpangels.com/blogs/innovation/corporate-america-designed -to -fall-part-1/

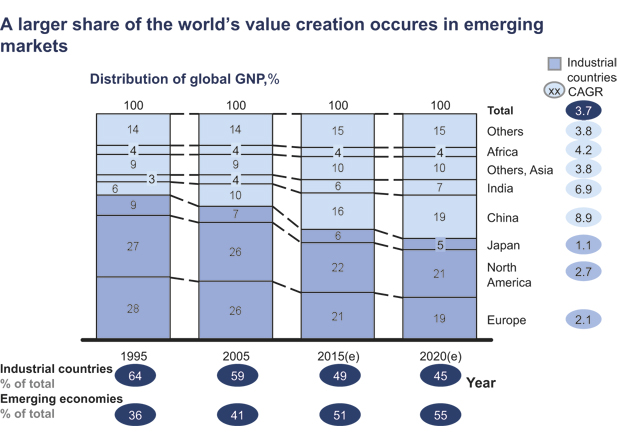

Trade barriers are increasingly being eliminated as international competition increases in many industries. This means that companies that only produce for the national market are also being exposed to international competition. Indirectly, changes in cost levels in exporting countries could therefore also affect the competitiveness of companies that only produce for a national market. Finally, an increasing proportion of value creation globally is taking place in emerging economies. This is illustrated by Figure 2.5.

Figur 2.5 Developments in the distribution of value creation globally in different markets (per cent).

Kilde: McKinsey Global Insight; McKinsey analysis.

These forces do not affect all companies to the same extent. Some industries remain largely national and the pace of change is also not as great in all industries. Nonetheless, the majority of the companies in the Ministry of Trade and Industry’s portfolio are exposed to these trends to some degree. It will become increasingly important for many companies to actively relate to emerging economies. Having a knowledge and experience of traditional core markets is no longer sufficient. These development characteristics have major implications for the management, boards and owners of the companies.

The companies must be adaptable and able to take fast decisions as and when commercial opportunities arise. For the day-to-day management of the companies, this will necessitate ongoing assessments and studies of potential strategic decisions. A good management team must therefore have a focus on external developments and trends, in addition to their focus on daily operations. International experience and networks are becoming increasingly important.

Boards must at all times have an active view of strategic issues and changes in competition preconditions. This requires a fundamental understanding of the company’s operations, the markets in which the company operates and the trends that affect the company. The appointment of a CEO will remain as important a task as it always has been. An appropriately composed board is therefore vital. The board should possess expertise that is relevant to the company’s current operations. This also means a knowledge of related industries which could shape the company’s development to a significant degree. International experience and insight represented on the board is also becoming extremely important for an increasing number of companies.

McKinsey notes that owners must expect to have to make decisions concerning major strategic realignments and investments more frequently than was previously the case. So as not to abandon the company’s own assessments, this will require owners to develop their own perspectives concerning the key developments and opportunities for their own companies. Owners must have their own perspectives on their company’s development even if they do not wish to be an active owner in relation to the company’s industrial and strategic development. Without such perspectives, it would be difficult to make decisions concerning key owner issues, such as acquisitions and share issues, quickly and in an appropriate way. In spite of this, given the complexity of decisions and the pace of reorganisation, owners will become increasingly dependent on the support of a competent and independent board.

As substantial changes in value must be anticipated between companies, with some companies increasing sharply in value and others falling sharply, it will also become increasingly difficult for an owner to have a static perspective on his ownership. Owners that actively buy and sell holdings in a large number of companies, known as ‘portfolio managers’, will seek owner exposure with respect to future winners whilst at the same time reducing their capital binding in companies and industries that are not considered to be future-proof. For their part, owners with a more long-term perspective on their ownership must ensure that they act as a driving force behind the company’s development rather than as a brake. Relevant issues could include the right timing and form of internationalisation, acquisitions or mergers with other companies. In spite of a long-term perspective on the actual holding in a company, it would be difficult to justify a static view of the company’s objectives. McKinsey also points out that long-term owners should have a strategy as regards what they want to achieve through their holding in each individual company.

2.2.3.2 More fragmented ownership in major listed companies

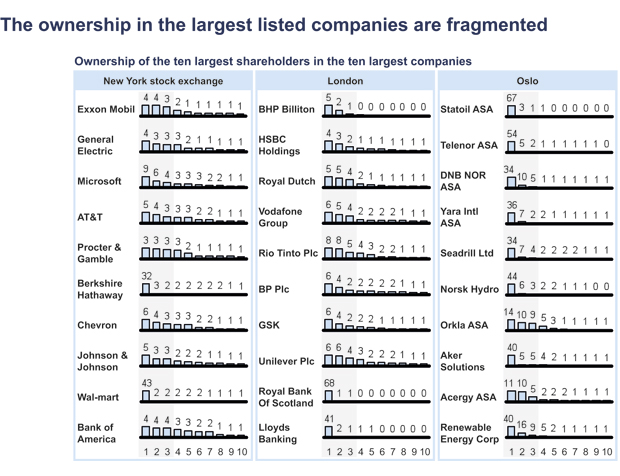

In most private listed companies, ownership is spread between a large number of institutional investors. The Government Pension Fund Global for example had an average holding in each of its companies of approx. 1 per cent in 2009 and yet is still frequently amongst the companies’ 20 largest shareholders. On average, the ten largest shareholders in each company on the stock exchanges in New York and London own 2914 per cent and 3015 per cent of the ten largest companies respectively; cf. figure 2.6.

Institutional owners, such as pension funds and collective investment funds, have typically spread their investments between a large number of companies and are therefore relatively inactive with respect to individual companies as regards the follow-up of strategic and financial development. They vote passively “with their feet” and sell their holdings in companies that they do not believe will generate an attractive return. This development has led many people to refer to such companies as “owner-less”. This ostensible absence of active ownership, which could have acted as a counterbalance to company management teams with potentially short-term financial incentives, is highlighted as a possible explanation of the financial crisis.

Figur 2.6 Ownership for the ten largest shareholders in the ten largest listed companies on selected stock exchanges (per cent).

Kilde: The 2008 Institutional Investment Report, Bloomberg.

The government-appointed Walker Committee in the United Kingdom discussed these issues and proposed the imposition of greater demands on owners and boards as appropriate tools. In the opinion of the committee, board members should be encouraged and expected to challenge the company management’s strategy proposals. In large, complicated companies, the role of board chairman is described as a role which requires two-thirds of a full-time post. The board should carry out a periodic self-evaluation and publish the results of this evaluation.

The imposition of requirements concerning active ownership on owners with very small shareholdings in a company is far from uncomplicated. Even Norges Bank, as administrator of the Government Pension Fund Global, one of the largest funds in the world, would find it difficult to allocate substantial resources to active ownership in all its approximately 8000 company investments. On the other hand, the problem of the “free rider” (or “freeloader”) is an obvious one if requirements are not imposed on all shareholders. As the owner of a 0.5 per cent share in a company for example, one could in an extreme case bear the entire cost of active ownership, yet receive only 0.5 per cent of the profit.

Another response to the phenomenon of “owner-less” companies is the emergence of very active owners, e.g. the group that is often referred to as ‘Private Equity owners’. Such owners focus on a limited number of companies and actively influence those companies. There is empirical evidence to suggest that the best of these owner environments are succeeding in creating added value by practising active ownership.

There seems to be a trend towards polarisation, where owners become either entirely passive with regard to a large number of companies in a broadly diversified portfolio or very active with regard to a limited number of companies in which they have a major shareholding.

The consequence of the fragmentation of the owner structure is that owners with substantial shareholdings, which the State usually has in its direct ownership, will not be able to expect the other owners to exercise active ownership to any significant degree. If the State does not exercise such ownership itself, it will therefore risk becoming entirely dependent on the company’s management and board taking decisions in line with the owners’ interests with regard to development of the company, the risks within the company and the return on equity. Unless the State has an active approach to the companies, it could put itself in a position where an owner vacuum is created in companies in which it is a major owner. This situation could be open to criticism by smaller shareholders who do not have the same influence or opportunity to exercise active ownership. Therefore, as the owner of substantial shareholdings, the State should, according to McKinsey, develop its own perspectives on the companies in which it has invested. These perspectives should form the basis for an assessment of suitable board compositions and of when and how one as owner should challenge the companies’ management teams. When the State succeeds in its active ownership, it could constitute an advantage compared with companies that only have institutional, passive owners.

2.2.3.3 Stronger focus on Corporate Governance

The debate surrounding corporate government accelerated in the wake of the company and accounting scandals in the late 1990s and early 2000s. These events led to requirements concerning the strengthening of internal controls and reporting within companies, a greater degree of transparency linked to the companies’ management-related circumstances (including remuneration of the management team), requirements concerning better accounting information, and requirements linked to independence and controls with the companies’ auditors. The requirements resulted in comprehensive framework legislation in some countries and many non-binding recommendations, including the OECD’s principles for corporate governance from 2004. In retrospect, the financial crisis has further reinforced the focus on this theme.

In 2004, the Norwegian Corporate Governance Board (NGCB) prepared the Norwegian Code of Practice for Corporate Governance, which has since been updated on a number of occasions. The recommendations are based on, and largely in accordance with, the most important corresponding international initiatives, and have amongst other things helped to clarify the distribution of roles between shareholders, boards and general management over and above that which follows from applicable legislation. The State has developed and published its own principles for its corporate governance, but it has also supported the NUES recommendations.

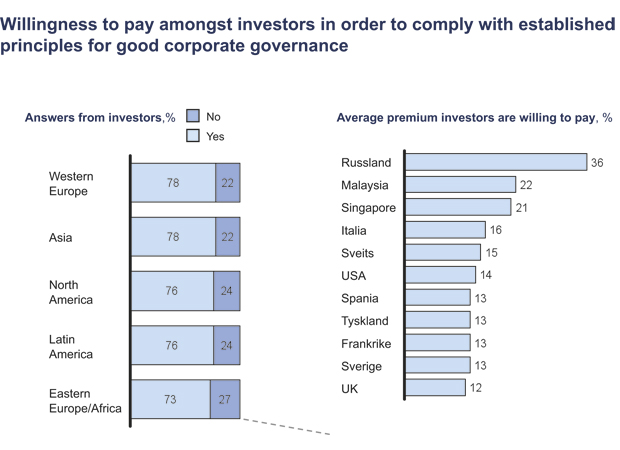

The strong focus on corporate governance has resulted in owners who fail to follow the recognised principles being subject to considerable criticism and the value of companies in which such owners have substantial shareholdings will very probably be adversely affected; cf. figure 2.7.

Figur 2.7 Willingness to pay amongst investors in order to comply with established principles for good corporate governance (proportion willing to pay a premium and average percentage premium).

Kilde: McKinsey Global Investor Opinion Survey on Corporate Governance, 2002

If the State is not seen as an owner which follows the rules for good corporate governance, it could not only adversely affect the value of the companies that the State owns; given the size of the State in the Norwegian stock market, the level of trust in the Norwegian stock market could also be weakened with a resultant fall in the market as a whole. It is therefore of great importance that the State as owner fully adheres to established principles for good corporate governance.

Strategies for different types of ownership

Different owners perform their role as owner in different ways. One of the distinguishing factors is the degree of active involvement and the way in which the owner becomes involved. McKinsey notes that, at a general level, three principal categories of owner can be distinguished: institutional and predominantly passive owners (such as Yale and Hermes), long-term strategic investors (such as Investor (Sweden, private) and Temasek (Singapore, State)) and owners with a focus on operational involvement (such as Private Equity companies). There are many examples of owners being successful within each of these models. Each category of owner has different methods for contributing to value creation.

Institutional investors generally focus on investment strategy and governance and are thus relatively passive owners, often with many small shareholdings in a large number of companies. The best of these institutions create value by distributing their investments based on specialist expertise and insight, clear guidelines for governance in the portfolio companies and by selling holdings that do not meet the owners’ expectations. This type of investor can actively influence companies in which they are one of the biggest shareholders by, for example, voting at the annual general meeting and maintaining a dialogue with the board chairman in connection with structural changes and other events of importance to future financial returns.

Long-term strategic investors often have a portfolio with a number of core companies – often with large shareholdings – which they monitor closely, partly so that they can also develop an industrial sector in a long-term perspective. Some of these owner environments exert considerable strategic influence and take the initiative to influence important strategic decisions and acquisitions. Owners often actively strive to pursue a merger- and acquisition-oriented agenda and establish and follow up financial objectives. Such owners are heavily involved in the appointment of the board and operate with a network of professional company managers and board members. McKinsey points to Investor, the State entities Temasek (Singapore) and Khazanah (Malaysia), Orkla, Industrivärden and Kinnevik as examples of long-term and strategic owners.

Owners with a focus on operational involvement become actively involved both in the strategic agenda and with regard to operational changes in collaboration with the company’s management. They often become heavily involved in the value creation process within each individual company and exploit economies of scope between companies in the portfolio, e.g. within corporate services and IT. Examples of owners with an active operational involvement are General Electric (GE) and many of the Private Equity (“PE”) funds, such as Blackstone. The PE funds’ investment managers for the individual companies usually sit on the boards of the companies in order to follow the agenda and developments within the companies on an ongoing basis.

McKinsey notes that the State as owner could benefit greatly from individual strategies that are used by highly capable institutional investors or long-term strategic investors in order to develop their corporate governance. Nevertheless, it is important to be clear about the board’s role and responsibilities and the fact that the cabinet ministers and ministry are not responsible for commercial decisions taken by the board. The government ministries are therefore not represented by their own members on the boards.