5 Sustainable use and good ecological status in ecosystems

5.1 Introduction

The Government’s main approach in its biodiversity strategy is to ensure that the nature management regime is sustainable, so that the overall pressure resulting from human activities and use of nature allows Norwegian ecosystems to maintain good ecological status over time as far as possible. This is the main theme of Chapter 5. Other important approaches to safeguarding biodiversity in Norway are action to protect threatened species and habitat types (Chapter 6) and the conservation of a representative selection of Norwegian nature for future generations (Chapter 7).

Many of the Aichi targets are essentially concerned with maintaining well-functioning ecosystems or improving ecological status, particularly numbers 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 14 and 15. The Strategic Plan for Biodiversity calls for action to ensure that ‘ecosystems are resilient and continue to provide essential services’ and that ‘biological resources are sustainably used’, and its targets include action to restore degraded ecosystems and maintain the integrity and functioning of ecosystems. These aims are reflected in one of Norway’s national environmental targets for biodiversity, which is that ‘Norwegian ecosystems will achieve good status and deliver ecosystem services’.1

The target of achieving good ecological status is based on the fundamental idea that well-functioning ecosystems benefit society as a whole, and that we have an obligation to pass on healthy ecosystems to future generations. The objects clause of Norway’s Nature Diversity Act also highlights the importance of the environment as a basis for human activity, culture (including Sami culture), health and well-being.

Healthy ecosystems are also of decisive importance for nature’s capacity to provide ecosystem services that human society depends on, such as pollination of food plants, climate regulation, flood control and clean drinking water. These are vital for human survival, for supplies of food and other raw materials, and for maintaining strong primary industries. Sustainable forestry, fisheries, aquaculture and agriculture depend on well-functioning ecosystems. Industries that use active substances, enzymes and genetic code from biological material to manufacture medicines, foodstuffs and other products are also responsible for substantial value creation. Moreover, healthy ecosystems are important for public health, for example by providing people with opportunities for emotional and aesthetic experience and for engaging in outdoor activities.

In connection with administrative decisions, it is necessary to find a balance between costs and benefits. In many cases, other public interests are considered so important that activities or developments that will disturb the natural environment are permitted. In other cases, the weight given to other public interests may mean that it is accepted that parts of an ecosystem will not achieve good ecological status. In addition, pressures that are not under national control, such as climate change, ocean acidification and long-range transport of pollutants, may make it impossible to achieve good ecological status in all parts of ecosystems.

In general, the status of Norway’s ecosystems is relatively good. A great deal has already been done to safeguard the natural environment, and Norway has introduced a wide range of legal and economic instruments that can be used in building up a sound, ecosystem-based management system. The most important legal instruments are the Planning and Building Act and sectoral legislation such as the Water Resources Act, the Watercourse Regulation Act, the Energy Act, the Pollution Control Act, the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act, the Marine Resources Act, the Aquaculture Act, the Petroleum Act, the Forestry Act and the Land Act, applied together with the Nature Diversity Act. Norway thus has a sound legislative basis for sustainable nature management. The Ministry of Climate and Environment has commissioned a report on experience gained during the first few years of the application of the Nature Diversity Act, and Chapters 6, 8 and 9 include some proposals for follow-up measures to improve the application of the Act and make it more effective. The Government also proposes some changes in the application of other legislation for the same purpose, for example amendments to regulations, changes in the weighting to be used when making individual decisions, and improvements in the guidance provided. When it considers the need for new economic instruments or changes to existing instruments, the Government will primarily consider the recommendations of the Green Tax Commission. Further information can be found in the sections of this white paper on individual ecosystems, and in Chapter 9 on the roles and responsibilities of the municipalities and counties.

However, Norway still has work to do in this field. One problem for the Norwegian authorities is the lack of clear, agreed management objectives for ‘good ecological status’ in most ecosystems, even though ‘sustainable’ management is specified as a goal in a number of statutes. The exceptions are coastal and freshwater ecosystems and to some extent marine ecosystems. Clearly defined and agreed management objectives for the different ecosystems would provide a better basis for making decisions in cases where a balance needs to be found between different interests and social objectives, and would help to achieve environmentally, socially and economically sustainable development. For Svalbard, there is an ambitious target of maintaining the virtually untouched natural environment, but in this case too, there is a lack of clear management objectives for ecological status. It is therefore difficult to judge whether current use is ecologically sustainable, and one result may be that policy instruments are not used effectively enough. In addition, land conversion and land-use change is still, overall, the most important driver of biodiversity loss in Norway. Furthermore, the Norwegian nature management system has not yet been adapted to take into account changes in ecosystems caused by climate change. In addition, there are specific problems in the different ecosystems.

In this chapter, the Government proposes specific action and tools to improve the sustainability of biodiversity management over time. More general measures are discussed first, followed by more specific measures for each of the major ecosystems. The section on wetlands includes an account of how the Government intends to respond to a request from the Storting (Norwegian parliament) concerning various issues relating to the management of peatlands.

5.2 The Nature Diversity Act

The Nature Diversity Act is one of the most important instruments that was adopted as a result of Norway’s first national strategy for the implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity (Report No. 42 to the Storting (2000–2001)). The Act applies to Norwegian land territory, including river systems, and to Norwegian territorial waters. Its provisions on access to genetic material also apply to Svalbard and Jan Mayen. Certain provisions of the Act also apply on the continental shelf and in the areas of jurisdiction established under the Act relating to the economic zone of Norway to the extent they are appropriate. According to the objects clause, the purpose of the Act is ‘to protect biological, geological and landscape diversity and ecological processes through conservation and sustainable use, and in such a way that the environment provides a basis for human activity, culture, health and well-being, now and in the future, including a basis for Sami culture’.

Experience gained so far from application of the Nature Diversity Act has played a part in the development of the Government’s biodiversity policy. Since the Act has only been in force for a few years, information on its effects is still limited. This applies particularly to its effects on the ecological status of ecosystems, which can only be assessed over a longer time period. In addition, the Act is only one of a number of policy instruments, and the state of the environment in the long term will depend on the combination of all policy instruments that are applied and the whole range of pressures and impacts on ecosystems.

The provisions of the Nature Diversity Act that are particularly relevant to this chapter are the general provisions on sustainable use, including general principles of environmental law (‘principles for official decision-making’, Chapter II), the provisions on species management (Chapter III) and the provisions on alien organisms (Chapter IV).

The Ministry of Climate and Environment commissioned a report from the consultancy firm Multiconsult on experience of the application of the principles of environmental law set out in the Act and its provisions on priority species, selected habitat types and exemptions from protection decisions, which was published on 30 September 2014. Additional information was obtained through talks with business organisations and others after the report was published.

The provisions on species management in the Nature Diversity Act were largely retained or transferred from other legislation – the Wildlife Act, the Act relating to salmonids and freshwater fish and the Nature Conservation Act. The provisions on alien organisms in the Nature Diversity Act, together with new Regulations relating to alien organisms, enter into force on 1 January 2016. These new rules will be important in preventing the import and release of invasive alien organisms. However, they will not provide a solution to all the problems associated with invasive alien organisms that are already established in the Norwegian environment. Eradicating, containing and controlling invasive alien organisms requires a great deal of time and resources, and complete eradication is not realistic. Priority measures are discussed in the sections on each ecosystem in Chapter 5.5. The Ministry of Climate and Environment will in consultation with other relevant ministries draw up an overall action plan describing priorities for eradicating, containing and controlling invasive alien organisms.

The provision of the Nature Diversity Act on quality norms for biological, geological and landscape diversity has only been used once, to establish quality norms for wild salmon stocks. This provision was not included when information on the application of the Act was being collected. Quality norms can be useful tools if there is agreement that a species or habitat type requires special safeguards, for example because a population is declining, but it is not clear what needs to be done and several sectors are involved in management. In such cases, establishing a quality norm can encourage the development of a joint knowledge base and joint targets for the management of the species or habitat type.

Multiconsult’s report recommends some steps to clarify the scope of the principles of environmental law and provide better guidance on how they should be applied in practice. These are being followed up during the revision of the guidelines on the application of the principles for official decision-making. In addition, the report makes recommendations on the application of the provisions on priority species and selected habitat types, and on improvements of the knowledge base and steps to build up expertise at local and regional level.

5.3 Developing management objectives for good ecological status

As mentioned above, one problem for the Norwegian nature management authorities is the lack of clear, agreed management objectives for ‘good ecological status’ in most ecosystems, with the exception of coastal and freshwater ecosystems and to some extent marine ecosystems. This results in differing views on the need for action and where to strike a balance between different interests. The Nature Diversity Act will continue to be an important tool for a cross-sectoral approach to sustainable nature management, particularly through general management objectives for species and habitat types, principles for decision-making, and instruments such as the designation of selected habitat types. However, the Act does not provide guidance on specific management objectives for good ecological status to be used in the overall management of each ecosystem.

Figure 5.1

An illustration of what is meant by good and poor ecological status, using sugar kelp forest as an example.

Source Illustration: Nyhetsgrafikk

The Ministry of Climate and Environment will initiate the development of scientifically based criteria for what is considered to be ‘good ecological status’. This will be carried out in close cooperation with relevant sectors, and will as far as possible be based on existing criteria and indicators. Defining what is meant by ‘good ecological status’ is the first step in developing management objectives for ecological status in different areas. It will not necessarily be Norway’s objective to achieve good ecological status everywhere. If other public interests weigh more heavily, it may be decided that it is acceptable for parts of an ecosystem not to achieve good status. In addition, pressures that are not under national control, such as climate change, ocean acidification and long-range transport of pollutants, may make it impossible to achieve good ecological status everywhere. The Government will develop management objectives for ecological status in the various ecosystems, and determine which types of areas or which parts of each ecosystem should achieve good ecological status, taking all necessary factors into consideration. Specific management objectives for ecological status are to be established by 2017. The work will include all the major ecosystems except for the areas that come within the scope of the Water Management Regulations.

Once the management objectives for ecological status have been established, the Government will organise the use of policy instruments with a view to maintaining ecological status in areas and ecosystems where it is already good enough and improving it in areas where ecological status is poorer than stipulated by the management objectives. The Government will use this system as a tool for making nature management more effective and for setting priorities for restoration projects in accordance with Aichi target 15. The Government’s aim is for a management system based on clearly defined objectives for ecological status to be in place by 2020.

While this management system is being developed, the Government will continue to apply sectoral legislation, the Planning and Building Act, the Nature Diversity Act and the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act to reduce pressure on the environment and safeguard areas that are important for biodiversity.

The Government will:

Initiate work to clarify what is meant by ‘good ecological status’, based on scientific and verifiable criteria.

By the end of 2017, establish management objectives for the ecological status to be maintained or achieved in Norwegian ecosystems.

Seek to put in place a management system based on clearly defined objectives for ecological status by 2020.

5.4 Overall land-use management policy

Given that land conversion and land-use change is still the most important driver of biodiversity loss in Norway today, the Government will seek to ensure that environmental considerations are incorporated into and as appropriate given priority in relevant decisions on land use. This applies to decisions taken by central government authorities and, equally importantly, to decisions taken as part of the municipalities’ land-use management responsibilities under the Planning and Building Act. The municipalities are important partners in biodiversity conservation, and their role is discussed in more depth in Chapter 9.

The Government uses two principles as a basis for land-use decisions that affect biodiversity. Firstly, the most valuable species, habitats and ecosystems should be safeguarded in connection with decisions on land conversion and land-use change. This requires good planning procedures and a sound, up-to-date knowledge base. Secondly, if a development or activity entails a risk of loss of or damage to valuable biodiversity, the preferred solution should generally be to locate it elsewhere. However, depending on the weight given to other important public interests, a different conclusion may be reached. These principles follow from the Nature Diversity Act together with sectoral legislation.

If, after weighing up all the advantages and disadvantages in a particular case, it is concluded that the negative consequences will have to be accepted, the competent authority should consider whether to require mitigation measures in accordance with the legal basis provided by the relevant legislation. In addition, restoration of areas that are damaged by temporary developments or activities should be required once these have ceased. If there are still significant residual impacts, it may be appropriate to lay down requirements for ecological compensation if the relevant legislation provides the legal basis for this. Sections 11 and 12 of the Nature Diversity Act on the user-pays principle and on environmentally sound techniques and methods of operation may have a bearing on the interpretation of the types of requirements that can be used. Ecological compensation does not apply to the area where a development is being carried out, but to restoration, establishment or protection of biodiversity in another equivalent areas, preferably nearby and containing the same type of habitat. Compensation measures may involve restoring degraded habitat, creating new areas of habitat or protecting areas that would not otherwise have been protected. Such measures are often complex in ecological terms and also costly, and should normally only be considered as a last resort.

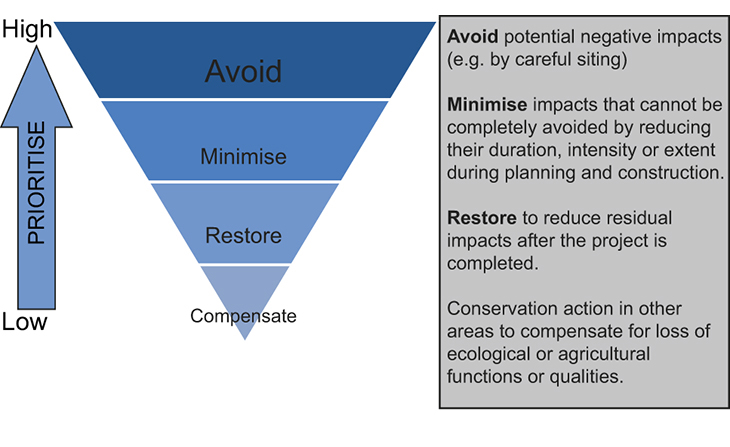

Figure 5.2 Ecological compensation

The figure shows the basic principles of the mitigation hierarchy and ecological compensation. The cheapest and most effective way of reducing negative impacts is always to avoid damage, and the preferred sequence of steps is to avoid or minimise damage, followed by restoration, with compensation as the last resort.

One of the main steps the Government is taking to ensure that Norwegian land-use management takes biodiversity properly into account is to obtain better spatial data on species, ecosystems and landscapes, see Chapter 8. Another approach is to strengthen municipal work on biodiversity and build up municipal expertise in this field, see Chapter 9. Furthermore, building up knowledge about the value of nature and ecosystem services, which is discussed in Chapter 4, will give a better basis for finding a balance between different interests. The Government also proposes specific uses of sectoral legislation for various ecosystems in Chapter 5.5 below.

Ecological coherence is of vital importance for maintaining biodiversity. Species need continuous or functionally connected areas of suitable habitat to allow mobility and the exchange of genetic material and ensure long-term survival. Because individual species’ needs vary so much, it is not possible to establish general guidelines on what provides ecological coherence. However, it is clear that climate change will make ecological coherence even more important. The habitat in species’ existing ranges will change as the climate changes, and many species will have to adapt by shifting to new areas. Areas that are important for ecological coherence may be found in any type of ecosystem. Types of areas that may be important ecological corridors include green spaces in towns and built-up areas; lakes, river systems and river mouths; and migration routes in the sea and on land. The term ‘green infrastructure’ includes all such areas.

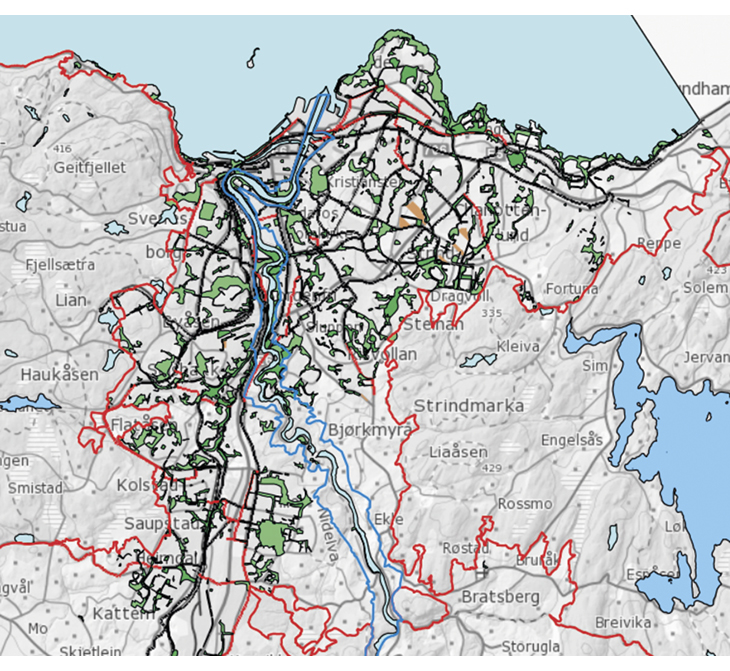

Figure 5.3 Map showing the green structure and the limit of the built-up zone (red lines) in part of Trondheim. The corridor along the river Nidelven is shown in blue. The map was produced using the municipality’s digital mapping tool.

Green infrastructure is not only essential for biodiversity, but also valuable for people, for example in connection with flood control and outdoor recreation. Such multiple benefits are an important reason why the EU has included the establishment of green infrastructure as one of the targets of its biodiversity strategy.

Land-use planning under the Planning and Building Act is Norway’s most important tool for establishing green infrastructure on land and out to one nautical mile from the baseline in coastal waters. Existing protected areas can also function as green infrastructure, and according to the Nature Diversity Act, protected areas may be established to promote the conservation of ‘ecological and landscape coherence at national and international level’. The most suitable tools for promoting ecological coherence will vary depending on the species involved and how much it is necessary to restrict the way an area is used to achieve the purpose in each case. The need to improve ecological coherence, particularly in the context of climate change, and how this can be achieved, will be further reviewed.

The Government will:

Continue to work towards a land-use management regime that takes biodiversity properly into account by ensuring a sound knowledge base and strengthening local and regional expertise on biodiversity and the values associated with it.

Further review the need to improve ecological coherence and how to achieve this.

5.5 Management policy for each of Norway’s major ecosystems

5.5.1 Marine and coastal waters

Norway’s system of management plans for sea areas is a tool for integrated, ecosystem-based management, in other words a management system that promotes conservation and sustainable use of ecosystems. Management plans have now been drawn up for all three of Norway’s sea areas: the Barents Sea–Lofoten area, the Norwegian Sea, and the North Sea and Skagerrak. The management plans have been published in the form of white papers submitted to the Storting.

The purpose of the management plans is to provide a framework for value creation through the sustainable use of natural resources and ecosystem services in the sea areas and at the same time maintain the structure, functioning, productivity and diversity of the ecosystems. The management plans are thus a tool both for facilitating value creation and food security, and for maintaining the high environmental value of the sea areas.

The management plans clarify the overall framework and encourage closer coordination and clear priorities for management of Norway’s sea areas. Activities in each area are regulated on the basis of existing legislation governing different sectors. The Government will continue to use the system of marine management plans.

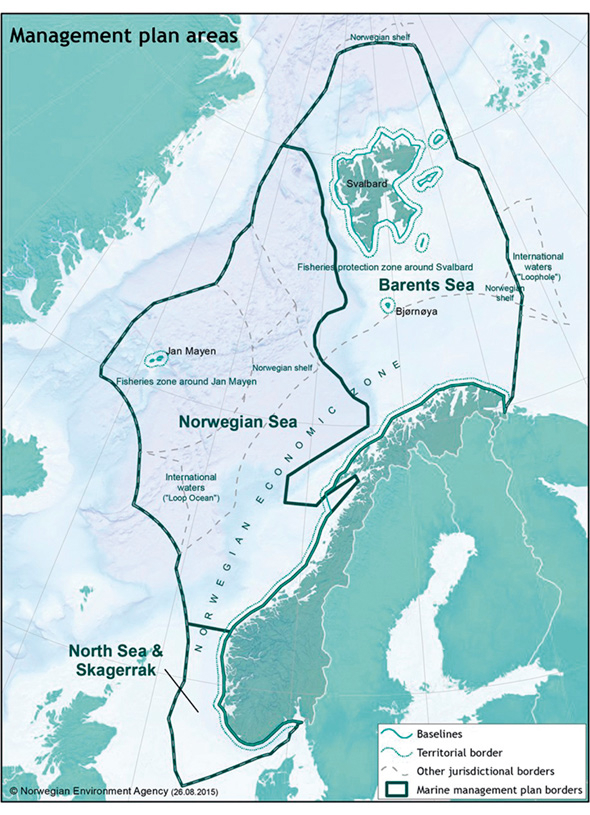

Figure 5.4 Map of Norway’s marine management plan areas.

Source Norwegian Environment Agency/Norwegian Mapping Authority

The Government’s initiative to develop clearer management objectives for ‘good ecological status’ in ecosystems (discussed in Chapter 5.3) will make it possible to target action and policy instruments to maintain and achieve good ecological status in marine ecosystems more precisely. The river basin management plans drawn up under the Water Management Regulations are the main instruments for achieving and maintaining good ecological status in waters out to one nautical mile outside the baseline. The Water Management Regulations are discussed further in Chapter 5.5.2.

Ensuring that maritime space is used in a way that takes proper account of biodiversity is just as important as land-use planning elsewhere. In waters out to one nautical mile outside the baseline, the main instrument for spatial planning is the Planning and Building Act. The Government is updating its advice on municipal spatial planning for areas in coastal waters. The aim is to ensure as much consistency as possible from one municipality to another, and to give clear guidelines for how biodiversity considerations should be incorporated into the planning process. The Government will also assess how marine spatial planning and land-use planning in the coastal zone can best be coordinated. This is important for species, habitats and ecosystems in the transitional zone between sea and land and how they are affected by local developments and pollution. The marine management plans include spatial management measures as tools for ecosystem-based management. The river basin management plans under the Water Management Regulations must include environmental objectives for water bodies. Approved management plans must be used as a basis for the activities of regional bodies and for municipal and central government planning and activities in the river basin district. Measures set out in the marine management plans and the river basin management plans are implemented in the usual way under the appropriate legislation and following normal administrative procedures.

The most important elements of the Government’s policy for sustainable management of marine and coastal waters in specific sectors are described below. Measures to protect threatened species and habitats and to ensure protection of a representative selection of Norwegian nature are described in Chapters 6 and 7.

Harvesting living marine resources

The Marine Resources Act provides a framework for sustainable harvesting of living marine resources. It requires management based on the precautionary approach in accordance with international agreements and guidelines, and using an ecosystem approach that takes into account both habitats and biodiversity. Management is also based on the best available scientific information. Harvesting methods and the way gear is used must take into account the need to reduce possible adverse impacts on living marine resources.

Mapping of the seabed, for example through the MAREANO programme, has documented that fisheries activities are having a considerable impact on benthic ecosystems in certain areas, and trawling has the strongest impacts. Trawls have been in use for more than a hundred years, and trawling has largely been concentrated in the same areas. In recent years, there has been a substantial reduction in trawl hours, partly because more fish have been available, and pressure on benthic habitats has therefore been reduced. The area trawled has also been smaller than in previous years. Technological developments are improving efficiency and resulting in trawling gear that has less environmental impact. The Government will continue to promote the development and use of trawling gear that has as little impact as possible on the seabed, and of devices in trawls that minimise unwanted bycatches.

The Regulations relating to sea-water fisheries contain a general requirement to show special care during fishing operations near known coral reefs. Many new coral reefs have been registered in Norwegian waters through the MAREANO programme and other projects.

Some fish species, including sandeels, herring and capelin, are defined as key species in ecosystems, and have a large influence on other elements of the biodiversity. They are important prey for a variety of marine mammals, other fish and seabirds, and their stock size has a major influence on populations of other species. Norway has chosen to introduce a new management model for the sandeel fishery in the North Sea. The aim is to build up viable spawning stocks throughout the part of the sandeel range that is within Norway’s Exclusive Economic Zone.

Figure 5.5 The Norwegian stock of European lobster is no longer considered to be threatened. One of the conservation measures the authorities have introduced is the closure of certain areas to lobster trapping.

Source Photo: Rudolf Svensen

The Government will continue to use a number of measures to build up the Norwegian stock of European lobster. Strict regulation of lobster catches will continue. There are still frequent breaches of the rules on lobster harvesting, and control and enforcement at sea will therefore continue. The closure of certain areas to lobster trapping is a suitable conservation measure for a relatively stationary species like the lobster, and has been shown to boost lobster numbers locally. The Government will assess whether further action is needed to prevent the American lobster from becoming established in Norway in addition to the prohibition on importing live American lobsters.

Aquaculture

Aquaculture can have negative environmental impacts. In order to play a part in biodiversity conservation, the aquaculture authorities will take into account all pressures and impacts associated with aquaculture activities, and not only direct impacts at each aquaculture site.

The aquaculture legislation includes a number of important tools designed to safeguard the environment, including requirements for monitoring the ecological status of the seabed below and near aquaculture facilities, criteria for authorising the use of areas for aquaculture and rules on the maximum permitted biomass of fish at each locality. There are also general operating rules, including requirements for fallowing for disease control, technical requirements to prevent fish escapes and rules on combating salmon lice and the removal of escaped farmed fish from rivers. The rules are constantly being further developed, and regulations were recently adopted making the industry responsible for funding measures to reduce the proportion of escaped farmed fish in rivers. The Government is also taking steps to strengthen the knowledge base in these areas.

The Government considers environmental sustainability to be the most important criterion for regulating further growth of the aquaculture industry, and will continue its work in line with the Storting’s decisions during its consideration of the white paper on predictable and environmentally sustainable growth of Norwegian salmon and trout farming (Meld. St. 16 (2014–2015)).

Petroleum activities

Environmental considerations are an integral part of Norwegian petroleum activities.

To protect marine ecosystems from pressures and impacts associated with the oil and gas industry, impact assessments under the Petroleum Activities Act are required both before new areas are opened for petroleum activity, and before specific field development projects. Impact assessments are also required before pipeline- and cable-laying, when fields cease production, and in connection with the disposal of installations. Further conditions apply in certain areas, for example restrictions on when drilling and seismic surveys are permitted in order to protect biodiversity and safeguard the interests of other industries.

An operator must obtain a permit under the Pollution Control Act before starting petroleum activities. Permits include conditions relating to releases to air and sea and preparedness and response to acute pollution, which depend on the vulnerability of the area in question and the available technology. For example, special requirements may be included to avoid adverse impacts on corals and other vulnerable benthic fauna, seabird populations, and fish stocks during the spawning season.

This system ensures that environmental considerations are integrated into all phases of petroleum activities from exploration to field development, operations and field closure, and helps to maintain good ecological status in Norwegian sea areas.

Shipping, ports and fairways

A high level of maritime safety and a satisfactory preparedness and response system for acute pollution are essential for preventing damage to biodiversity. The Norwegian Coastal Administration continually seeks to optimise maritime safety, preparedness and response measures. These must be designed on the basis of information about the probability of accidents and their possible consequences for life, health and the environment. In 2016, the Government plans to submit a white paper containing an overall review of maritime safety and the preparedness and response system for acute pollution.

Norway’s National Transport Plan 2014–2023 states that the principles set out in the Nature Diversity Act must be followed when planning, constructing and operating transport infrastructure. Large-scale developments often require an environmental impact assessment, which must include a description of potential impacts on biodiversity.

Shipping in polar waters, as in other parts of the world, is subject to the rules of international conventions adopted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The Polar Code, which was adopted by IMO in 2014, is a mandatory international code of safety for ships operating in polar waters. The Code consists of two parts, one on safety and one on environment-related matters. It sets specific requirements for ships operating in polar waters, for example on ship design, equipment, operations, environmental protection, navigation and crew qualifications. The most important environment-related provisions deal with pollution by oil, chemicals, sewage and garbage released from ships. The Polar Code enters into force on 1 January 2017.

Norway’s Act relating to ports and navigable waters is intended to facilitate safe and unimpeded passage and sound use and management of navigable waters in accordance with the public interest. The public interest includes biodiversity considerations. These must be taken into account when considering applications for permits for works under the Act. ‘Works’ in this connection include quays, bridges, aquaculture facilities, cables, pipelines, dredging and dumping. The Act also includes provisions on the use of navigable waters, aids to navigation and port activities.

Invasive alien organisms

There is a high risk of the introduction of alien organisms when ships discharge untreated ballast water, and these may displace native organisms. Climate change means that the risk that such organisms will become established is rising. Norway regulates ballast water management through its national Ballast Water Regulations, which entered into force in 2009. The regulations will be revised once the Ballast Water Convention has entered into force, which is expected to happen in the near future.

Figure 5.6 The Pacific oyster is an alien species in Norway, and there is a high risk that it will have negative impacts on Norwegian coastal ecosystems. The Government will give priority to efforts to contain and control the species.

Source Photo: Kim Abel/Naturarkivet

The Government will give priority to efforts to contain and control the Pacific oyster in accordance with the forthcoming action plan for the species. The Government will continue the current management approach for red king crab, which is to regulate the commercial fishery in the eastern part of its distribution area in Norway and encourage harvesting of all sizes of crabs to control the species further west.

Plastic waste

Sound waste management is essential for preventing marine litter. Dumping of waste is forbidden, and there are requirements to search for and report lost fishing gear. The Government has reinforced efforts at both national and international level to prevent littering of coastal and marine areas, and to build up knowledge about the sources of litter, its impacts and possible action against marine litter and microplastics. More support has been made available for voluntary beach clean-up campaigns. A producer responsibility scheme for leisure craft is being considered, and in 2016 the Norwegian Environment Agency is to present a review of other effective national action to deal with marine litter. The Agency will also publish an assessment of possible measures to reduce and prevent microplastic pollution of the marine environment. A cooperation project has been started in which fishermen can enter into a voluntary agreement with the Environment Agency allowing them to deliver waste they retrieve during fishing operations free of charge in port. The waste is then registered and as much as possible of it is recycled. The scheme currently applies to four Norwegian ports, and the data collected will be used in identifying solutions to the problem of marine litter. The Directorate of Fisheries will continue to run its annual retrieval programme for lost fishing gear. The authorities also intend to complete the work of removing abandoned mussel cultivation facilities. Norway will continue to play an active part in international efforts, mainly organised by the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA), the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (the OSPAR Convention) and the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC), to reduce the quantities of plastic waste and microplastics in the marine environment, build up knowledge about microplastics and prevent losses and ensure retrieval of fishing gear.

The mineral industry

In recent years, the mineral industry has shown growing interest in potential mineral deposits on the Norwegian continental shelf. The knowledge base is inadequate at present, and mapping and surveys are therefore the key activities. It will be some time before any commercial extraction of minerals can be started, and this would require more knowledge about the resource base, extraction methods, coexistence with other industries, and benthic species and habitats. Unless precautions are taken, activities on the seabed can damage rare and vulnerable species and habitats. The permanent footprint of mineral extraction should be minimised. Before any mineral activities can be permitted on the continental shelf, the knowledge base, including knowledge of environmental impacts, must be improved and sound legislation must be in place.

Offshore energy

The Offshore Energy Act entered into force on 1 July 2010. Under the Act, offshore renewable energy production may only be established after the public authorities have opened specific geographical areas for licence applications. Before an area can be opened for offshore wind power development, the Act also requires the central government authorities to carry out a strategic environmental assessment (SEA). One important purpose of drawing up the Offshore Energy Act was to ensure that a framework was in place well before any developments started and to maintain control of spatial planning offshore.

As part of the implementation of the Act, a working group led by the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate identified areas it considered to be suitable for wind power. The Directorate then conducted an SEA for these areas, which was submitted to the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy in 2013. The SEA was comprehensive, and included an evaluation of environmental, economic and business interests associated with the areas and their suitability in technological and economic terms. The Directorate concluded that five areas should be given priority for wind power developments. None of these has as yet been opened. Under the Offshore Energy Act, environmental impact assessments must be conducted in connection with licence applications, and detailed plans for each project must be drawn up.

5.5.2 Rivers and lakes

Integrated management

Cross-sectoral cooperation on water management under the Water Management Regulations (which incorporate the Water Framework Directive into Norwegian law) is an important tool for achieving good ecological status in Norway’s rivers and lakes. The management plans for river basin districts include environmental objectives for water bodies and programmes of measures.

The measures included in the river basin management plans drawn up for the period 2016–2021 are to be operational in 2018 at the latest, so that it is possible to achieve the national target of good ecological status by 2021. This has involved cooperation between sectors to put together sets of measures to reduce negative impacts and achieve environmental objectives. Further work will be carried out on the impacts of salmon lice and escaped farmed fish on wild salmon stocks. The Government will ensure the coordination of efforts by all relevant sectors to put the programmes of measures set out in the river basin management plans into operation so that the environmental objectives can be met. Decisions on the implementation of specific measures will be taken by the competent authority in each case under the relevant legislation.

Planning for river systems and adjacent areas

According to section 1–8 of the Planning and Building Act, the natural and cultural environment, outdoor recreation, landscape and other public interests in the 100-metre belt along the shoreline and along rivers and lakes must be given special consideration in planning processes. The same section also requires municipalities to consider whether developments that will have a negative impact on the environment should be specifically prohibited in this belt. Most municipalities have now introduced a prohibition against building along rivers and lakes. The Government considers it vital that municipalities and county authorities are aware of the importance of different ecosystems in climate change adaptation. For example, riparian ecosystems and floodplains can moderate the impacts of flooding, and should be retained as far as possible in planning processes. Section 11 of the Water Resources Act gives the municipalities the authority to determine the minimum breadth of the natural vegetation belt to be maintained along river systems to counteract runoff and provide a habitat for plants and animals. The Ministry of Climate and Environment, in consultation with the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy and the Ministry of Agriculture and Food, will ensure that the municipalities receive advice on how to apply this provision.

Works in river systems

River systems are an essential and characteristic element of Norwegian nature, and also an important source of renewable energy. The legislation on river systems makes licences mandatory for all works in river systems that may significantly affect public interests. The competent authority may lay down necessary conditions for such works. Hydropower developments have brought about the greatest physical disturbance of Norway’s river systems, but are also the backbone of the Norwegian electricity system and of vital importance to people’s welfare.

As a general rule, a licence is required to construct and operate a new hydropower installation. However, small-scale installations are generally exempt from the licensing requirement and are dealt with under the Planning and Building Act. Licences contain conditions relating to nature management and mitigation measures. The flow dynamics and variation in water flow are generally key to the value of a river system as a landscape element and for outdoor recreation and biodiversity. Licences therefore frequently include a requirement to maintain a minimum water discharge, or environmental flow, in order to maintain more of the connectivity and flow dynamics of the river channel.

During licensing processes, the water resources authorities will attach special importance to adjusting flow regimes to maintain the ecology of river systems in the best possible way. This applies both during licensing of new hydropower installations and procedures to alter the conditions for operation of existing installations. The use of measures to improve ecological status that will limit power production must be considered on the basis of an overall cost-benefit assessment of the effects on public and private interests.

The competent authorities include standard conditions, including conditions relating to nature management, in all new licences for hydropower installations. The conditions relating to nature management have been developed through experience of river system management, and make it possible to require licensees to investigate the impacts of hydropower production on the ecology of river systems, and to take certain steps to reduce the adverse impacts of developments, for example replenishing spawning gravel or removing barriers to fish migration.

Requiring licensees to investigate the long-term environmental impacts of hydropower developments makes it possible to identify whether further mitigation measures are needed. The authorities can also use the accumulated knowledge and experience of the impacts of earlier hydropower developments in determining the conditions that should be included in new licences. Furthermore, this knowledge and experience will provide a better basis for assessing the cumulative environmental effects if new developments are permitted.

The Government intends to make more active use of the standard nature management conditions to improve ecological status in river systems where there are hydropower developments.

The Norwegian river basin management plans point out that many of the current licences for hydropower developments lack the standard nature management conditions.

It is true that about half of all current hydropower licences lack the standard nature management conditions, which have only been included in all new licences since 1992. However, there is legal provision for requiring improvements of ecological status, even though the older licences do not include the modern nature management conditions. The water resources legislation provides for the licensing authority to revise the conditions for licences after a certain number of years, provided that certain requirements are met. This provides a tool for modernising the conditions in licences to bring them more closely into line with current environmental standards. It is possible to incorporate the standard nature management conditions when licences are revised, and subsequently to require the licensee to take action to improve ecological status or to carry out investigations to allow an evaluation of which measures are needed. The problem is that a revision process can be very time-consuming and resource-intensive, and that measures to improve ecological status are needed in many areas affected by older hydropower developments. The scale of the administrative resources required means that it may take a long time to achieve the environmental objectives for rivers where there are older hydropower developments.

The Government will review more efficient ways of making the standard nature management conditions or other effective instruments applicable, in the first instance to river systems regulated by hydropower licences where there are known to be environmental problems. This will be done with a view to requiring action to achieve the nationally approved environmental objectives in the river basin management plans for the period 2016–2022.

Within certain limits, the energy authorities can through a revision process require measures to improve ecological status that will affect power production, for example requirements to maintain a minimum water discharge. This cannot be done using the standard nature management conditions. The Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate and the Norwegian Environment Agency have carried out a joint screening study of all river systems where revision of hydropower licences can be started by 2022, covering about 395 licences in 187 river systems. The report assesses the environmental qualities that can be maintained through cost-effective measures that will involve some reduction in electricity production. The two agencies recommend giving high priority to 50 river systems where they identified a high potential for significant improvements in ecological status with only a small or moderate estimated loss in power production. On the basis of an overall national cost-benefit analysis, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy and the Ministry of Climate and Environment have instructed the river basin district authorities that as a general rule, requirements relating to minimum flow and/or water levels in regulation reservoirs are only to be used as a basis for achieving environmental objectives in the 50 high-priority river systems.

A good many hydropower licences will be revised during the first management cycle for Norway’s river basin districts. During this period, it may also be appropriate to require measures to improve ecological status in river systems other than the 50 high-priority river systems. This can be done by applying the standard nature management conditions, requiring licensing of older hydropower developments (some of these have never had licences, see the next paragraph), or amending individual conditions in certain hydropower licences. The Government expects sparing use to be made of proposals to require licensing of previously unlicensed developments or to amend conditions in licences in a way that would reduce electricity production. If the competent authorities for the river basin districts nevertheless consider that water flow requirements should be given priority in some of these river systems, they must provide grounds for their conclusions in the management plans. A new cost-benefit analysis must be made during the second management cycle (2022–2027).

There are still some older hydropower developments for which no licences have ever been issued. In special cases, the authorities have the legal power to require licensing of such developments. The authorities will assess on a case-by-case basis whether to use such processes as an opportunity to improve the ecological status of river systems if there are strong environmental grounds for doing so. In such cases, the standard nature management conditions will be included during the licensing process. A better overview is needed of unlicensed hydropower developments, including hydropower plants, and where they are located. The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy and the Ministry of Climate and Environment will together survey unlicensed developments and draw up an overview.

There may also be other grounds than improvement of ecological status for operational adjustments or altering conditions in licences, for example relating to landscape considerations or outdoor recreation interests. Revision of licences and other tools provided by the water resources legislation can also be used to achieve improvements for these interests. River systems that are protected against hydropower developments are discussed in Chapter 7.3.

Management of wild salmonids

Norway bases its management of wild salmon stocks on international management principles adopted by the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization (NASCO) and on a policy document on the protection of wild Atlantic salmon (Proposition No. 32 (2006–2007) to the Storting). Norway’s objective is to maintain and rebuild salmon stocks of a size and composition that safeguards the genetic diversity of the species and makes full use of the productive capacity of salmon habitat.

The system of national salmon rivers and fjords gives about three-quarters of Norway’s overall salmon resources special protection in selected river systems and fjords. This system is to be evaluated in 2017. If it is not considered to be providing adequate protection for wild salmon, the Government will assess the need to provide stronger protection against the effects of human activity.

The quality norms for wild salmon lay down guidelines for management objectives for salmon stocks. They clarify what is meant by ‘good status’ for a wild salmon stock. The Ministry of Climate and Environment will ensure that the classification of the most important salmon stocks in accordance with the norms is continued. If some stocks do not meet the criteria for good status in accordance with the norms, and there are no exemptions from the requirements in or under the norms, the Ministry will, in consultation with the relevant authorities, seek to clarify why good status has not been achieved and draw up a plan for how the norms can be achieved.

The Government will continue efforts to eradicate the salmon parasite Gyrodactylus salaris from river systems in accordance with scientific advice, mainly by treating rivers with rotenone. As of 1 July 2015, the parasite had been eradicated from a total of 22 infected river systems. Treatment of a further 17 river systems had been completed, and it is hoped that they can be declared free of the parasite within the next five years.

Although for many salmon stocks, fishing is not the main threat, regulating fishing in rivers and the sea helps to reduce the overall pressure on wild salmon and thus ensure the survival of certain stocks New regulatory measures for fishing for anadromous salmonids will be introduced in 2016. These will focus on sustainability and value creation. The Government is also seeking to ensure that fishing in the Tana river system is sustainable from 2017 onwards. Cooperation with Russia on the management of wild salmon in the Finnmark and Murmansk region will be followed up in accordance with a memorandum of understanding between Norway and Russia.

The Government will continue to make use of gene banks to safeguard the genetic diversity of salmon and sea trout stocks and to safeguard stocks that are threatened by Gyrodactylus salaris. However, the Government’s long-term aim is to be able to restock the rivers from which these stocks originate, and for the stocks to be able to survive in the wild.

The Government will continue the liming programme for rivers and lakes to counteract the effects of acid rain. Liming improves conditions not only for wild salmon, but also for biodiversity in general. There are now 21 salmon rivers in the liming programme, and after many years, a large number of salmon stocks have recovered. Of the wild salmon caught in Norway, 10–15 % are now from rivers that are in the liming programme.

Action to reduce the negative impacts of salmon lice and escaped farmed fish is discussed in the section on aquaculture in Chapter 5.5.1.

Regulation of pollution

Section 8 of the Pollution Control Act states that ordinary pollution from agriculture is permitted unless otherwise specified in regulations issued under section 9 of the Act. Regulations on the storage and use of fertiliser products of organic origin have been adopted to prevent pollution and to promote sustainable soil management and ensure that biodiversity concerns are taken into account when they are used. The Government is revising these regulations, and one of the aims is to reduce pressure on water bodies in agricultural areas.

Some pharmaceuticals that pose a significant risk to the environment have been included on a Watch List under the Water Framework Directive. All the EU member states are required to monitor the concentrations of these substances in water bodies. In addition, the environmental effects of pharmaceuticals are considered when making decisions on whether to grant marketing authorisation for their use in veterinary medicines. Waste water treatment plants are not designed to remove pharmaceuticals. Because of the environmental damage that pharmaceuticals can cause, it is important to inform the public about how to dispose of unused medicines. The Ministry of Health and Care Services has therefore asked the Norwegian Medicines Agency, together with the pharmacies and the pharmaceutical industry, to inform the public about the pharmacies’ take-back scheme for unused medicines.

Alien organisms

The new Regulations relating to alien organisms (in force from 1 January 2016) introduce a requirement to hold a permit for the import or release of a long list of aquatic plants and other organisms. Steps to deal with alien fish species will be based on these regulations and on a forthcoming action plan for combating alien exotic fish species. Action to contain and control Canadian pondweed and Nuttall’s pondweed will also be organised within the framework of the action plan for the two species.

5.5.3 Wetlands

Introduction

One element of the Government’s policy for sustainable use and good ecological status in wetlands is its follow-up of a request from the Storting dated 2 June 2015. The Storting decided to send this request in connection with a debate on proposals for integrated long-term management of peatlands in Norway. The Government was asked to assess relevant issues relating to the management of peatlands in its white paper on Norway’s biodiversity action plan and in white papers on agriculture and on the forestry and wood industry.

Threatened species and habitat types associated with wetlands, and action to protect them, are discussed in Chapter 6.4.3, and measures to ensure conservation of a representative selection of wetlands are discussed in Chapter 7.3.3.

Many wetlands are still under considerable pressure, although the situation has improved in some respects in recent years. Because of the importance of wetlands for biodiversity and carbon storage and their potential importance in flood control and drought mitigation, the Government will intensify efforts to improve the ecological status of priority areas so that remaining wetlands are safeguarded.

Internationally, the importance of wetlands has been recognised for many years, and the Ramsar Convention provides a global framework for the conservation and wise use of wetlands. The 168 countries that are parties to the convention have drawn up a fourth strategic plan for the period 2016–2024 that each country is expected to implement. Norway is doing so as part of the action plan in the present white paper. The conservation and sustainable use of peatlands was one of the topics discussed at the 12th Conference of the Parties to the Ramsar Convention in June 2015. A resolution adopted at the conference encourages all countries to limit ‘activities that lead to drainage of peatlands and may cause subsidence, flooding and the emission of greenhouse gases.’ The Nordic countries played an active part in the adoption of this resolution, and the Nordic environment ministers have agreed to join forces to strengthen efforts for the conservation and restoration of peatlands.

The Government will ensure that the values and benefits associated with wetlands, including peatlands, are given greater weight in the application of sectoral legislation and the Planning and Building Act. This will include providing better guidance on the importance of incorporating the values and benefits associated with wetlands, including peatlands, into municipal land-use planning, and how this can be done. The Government will also encourage municipalities to use natural flood control, including maintenance and restoration of riverbank, wetland and ecotone vegetation, as an integral part of their climate change adaptation work. The official Government expectations for regional and municipal planning make it clear that municipalities and county authorities need to be aware of the importance of different ecosystems for climate change adaptation. This also applies to the county governors, whose responsibilities include providing guidance for the municipalities in climate change adaptation. Ecosystems such as wetlands, river banks and forest can moderate the impacts of climate change, and their conservation should therefore be included in land-use planning processes. The Government expects municipalities and county authorities to take particular note of natural hazards and future climate change, and to identify important values associated with biodiversity and maintain them through regional and municipal planning. It is important to keep track of developments, and the Government will therefore ensure that the municipalities report on permits for land-use change in wetland areas in the same way as for cultivation of new areas. If important public interests make it necessary to allow developments on peatland, excavated material should as far as is practicable be used in the restoration of other peatlands.

Use of peat

Norwegian potting soil may contain a high proportion of peat extracted from peatland, often imported from other European countries. Peat extraction damages plant and animal habitats and results in greenhouse gas emissions. Industrial peat extraction is one of the major pressures that is causing degradation of peatlands internationally. It is therefore important to make consumers aware that it is possible to use soil that does not contain peat for gardens. The Government will consider requiring producers to provide clear labelling of the contents of soil products. The need for soil improvers and growth media could in principle be met by using other renewable resources. However, phasing out peat may result in more use of replacements, for example imported coir (coconut fibre). It is important to ensure that switching to other products will result in a real environmental improvement. The Government will therefore review the consequences of phasing out the use of peat more thoroughly.

In June 2015, the Storting debated proposals for integrated long-term management of peatlands in Norway, and decided to request the Government to amend Norway’s regulations on environmental impact assessment (EIA) as soon as possible to make an EIA mandatory for peat extraction projects below the current limits, i.e. total volume extracted less than 2 million m3 or site surface area less than 150 hectares. This issue will be further reviewed during the revision of the Norwegian regulations to bring them into line with the revised EU Directive 2014/52. The deadline for implementing the directive is spring 2017.

Sustainable forestry to safeguard wetlands

The construction of new drainage ditches in connection with forestry operations is forbidden, but already existing ditches may be cleared. In certain areas, it may be necessary to maintain old ditches so that timber production does not decline. However, clearing old, more or less blocked ditches in areas where no productive forest has been established can dry out active peatland and swamp forests. The Government intends to revise the regulations on sustainable forestry to prohibit both the construction of new drainage ditches and clearing of old ditches in areas where no productive forest has been established. This will be further discussed in a forthcoming white paper on forestry from the Ministry of Agriculture and Food.

Regulations on new cultivation of land

The updated cross-party agreement on climate policy from 2012 includes a decision to revise the regulations on new cultivation of land to reflect climate change considerations. The Government is considering how to do this, and will among other things commission a review of the impacts of various measures relating to new cultivation of peatland, focusing on their mitigation effect and cost. The option of prohibiting new cultivation in peatland areas will also be considered. The Government will hold a public consultation process on the proposed amendments to the regulations after the review has been published.

Restoration of wetlands

Peatland restoration improves ecological status, and will also improve and increase the areas of suitable habitat for many threatened species. Peatland restoration, together with improvements of ecological status as required by the river basin management plans, is the Government’s most important approach to implementing the international target of restoring at least 15 % of degraded ecosystems.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), peatland restoration is one of the most cost-effective ways of reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural sector globally. A 2010 report on measures and instruments for achieving Norway’s climate targets by 2020 (Climate Cure 2020) also found this to be a cost-effective measure, with an estimated price of NOK 168 per tonne CO2. Restoration of peatlands and other wetlands can also be a useful climate change adaptation measure. Intact wetlands, particularly those that are fed by rivers, can provide protection against destructive flooding. In addition, they can reduce the impacts of drought. Restored peatlands can start to build up a peat layer again and thus store more carbon. However, this is a very slow process. When peatlands are first rewetted, methane emissions will increase. However, in the long term a net increase in carbon storage is expected.

In 2015, the Ministry of Climate and Environment started a three-year pilot project on peatland restoration. The aims for the sites that are included are to stop greenhouse gas emissions, enhance their role in climate change adaptation and improve ecological status. Most of the localities included in the pilot project are within protected areas. At the same time, a project for river system and wetland/peatland restoration was established by a committee of directorates under the Water Management Regulations to ensure the necessary cooperation and coordination of initiatives in these areas. It is intended to facilitate the implementation of Norwegian restoration initiatives, encourage the exchange of information and experience, and assess possible mechanisms for closer coordination of planning and funding of projects where authorities from several sectors are involved.

As part of its efforts to strengthen the national cross-party agreement on climate policy, the Government will draw up a plan for expanding restoration initiatives for peatlands and other wetlands as a climate policy measure in the period 2016–2020. Restoration will be organised so that projects play a part in achieving the Government’s goals for climate change mitigation and adaptation and for improvements in ecological status. The Norwegian Environment Agency and the Norwegian Agricultural Agency are responsible for drawing up the plan, which is to be completed in the course of 2016.

5.5.4 Forest

Forest management in Norway is strongly influenced by the forestry legislation and the way it is applied in practice.

Strengthening environmental concerns in forestry

As announced in the 2011 white paper on agricultural, forestry and food policy, the Government will give greater weight to environmental concerns in forestry by making use of the instruments introduced in the Nature Diversity Act and policy instruments for the forestry sector, including environmental inventories, knowledge development and application of the Norwegian PEFC standard, so that more biomass can be harvested from Norwegian forests while at the same time maintaining biodiversity. This will be discussed further in the forthcoming white paper on forestry policy from the Ministry of Agriculture and Food.

Regulations on sustainable forestry

Regulations on sustainable forestry under the Forestry Act are Norway’s key legislation for managing forest areas that do not have statutory protection. The Government considers that any intensification of forestry involving an increase in timber harvesting should be combined with stronger environmental measures in forestry. The Government will discuss this further in a forthcoming white paper on forestry policy.

Grant scheme for forestry management plans and environmental inventories

For many years, the Ministry of Agriculture and Food has provided grants for forest owners who draw up forestry management plans for their properties. Landowners generally engage private companies to obtain the necessary information and draw up the plans, and often many forest owners in the same area will commission forestry management plans at the same time, so that data collection takes place over a larger area.

Since 1990, it has been a condition for awarding grants that forestry management plans also include information on important environmental features of the forest property. Since 2000, there has been a requirement to record important habitats for red-listed species according to a specified method (known as environmental inventories in forest) on the basis of research on red-listed species and their habitat requirements. Environmental information acquired in this way provides a basis for environmental measures carried out done by the owners, and in addition the information from environmental inventories often provides a basis for voluntary protection of forest.

By 2015, about 70 000 areas covering a total area of about 750 square kilometres had been identified through environmental inventories and set aside as key biotopes that are not to be felled. This corresponds to almost 1 % of the total area of productive forest. Since environmental inventories have not yet been carried out for all forest properties, the proportion of productive forest set aside as key biotopes is expected to increase.

Regulations relating to the planning and approval of forestry and farm roads

Norway adopted new regulations on the planning and approval of forestry and farm roads in May 2015. The Ministry of Agriculture and Food will issue a circular on the regulations describing how to proceed if applications are received for the construction of forestry roads where subsequent logging may damage forest areas of high conservation value. The intention is to ensure that the environmental authorities, in consultation with the forestry authorities, investigate whether protection on a voluntary basis is a possibility in such cases. If the forest owner is interested in protection on a voluntary basis, the necessary procedures will be started. If not, the application for road construction will be processed in the normal way in accordance with the regulations.

Management of forest cervids

Moose, roe deer and red deer are the cervids that are mainly associated with forests in Norway. The fallow deer is an alien species, and is found in Østfold county. The Nature Diversity Act and the Wildlife Act and regulations under these acts provide the general framework for cervid management in Norway. The specific regulations on the management of cervids are of key importance. They require the municipalities to determine objectives for stocks of moose, red deer and roe deer in areas where hunting is permitted. The Government considers it important to organise cervid management locally.

Cervid populations in Norway have grown strongly after the Second World War. Moose stocks have for a time been too large for the available grazing resources in parts of the southern half of Norway. Grazing damage as a result of record-high cervid densities is costly for the forestry industry. Large populations of cervids also have a negative effect on traffic safety because the risk of deer-vehicle collisions rises. The Ministry of Climate and Environment will encourage steps to make information on cervids available to user groups and promote knowledge-based management of cervid populations to minimise negative density-related effects such as grazing damage and deer-vehicle collisions.

Invasive alien organisms

Foreign tree species can have negative impacts on native biodiversity. Planting and sowing of such species is regulated by the Regulations relating to the release of foreign tree species for forestry purposes under the Nature Diversity Act. The Ministry of Climate and Environment will continue to administer the regulations, and will in consultation with the Ministry of Agriculture and Food revise the guidelines on the regulations and publish a new edition. Another aim is to simplify administrative procedures for planting foreign tree species that are to be used as Christmas trees. In such cases, it may be appropriate to require notification rather than an application for a permit. In this context, there will be a focus on control of the spread of foreign tree species.

The spread of foreign tree species from sites where they have been planted earlier can also be a problem, particularly in protected areas. The administrative authorities for these areas will play an important role in containing and controlling the undesirable spread of foreign tree species, see Chapter 7.2 on management of protected areas. The Government will discuss appropriate measures to be used outside protected areas in the forthcoming white paper on forestry policy.

5.5.5 Cultural landscapes

The Government’s position is that it is neither possible nor desirable to revert to the agricultural techniques that were common fifty years ago. Nevertheless, action to maintain the ecological status of areas of cultural landscape is important.

Figure 5.7 Active and targeted management is needed to maintain biodiversity in cultural landscapes. The effects of grazing vary between species and breeds of livestock because of differences in their feeding preferences. Sheep and goats keep down shrubs, benefiting species that are threatened by overgrowing of open landscapes.

Source Photo: Jan O. Kiese

The environmental programmes and grant schemes in the agricultural sector are intended to reduce pressures and impacts associated with agriculture and to maintain the cultural landscape. A number of them also result in improvements in agricultural practices and boost production. Most of the environmental grant schemes in the agricultural sector are part of the Agricultural Agreement between the state and the farmers, and are organised in environmental programmes at national, regional and municipal level. The national environmental programme provides a central framework and national goals and includes key grant schemes for the whole country. The regional environmental programmes include grant schemes at county level, adapted to the environmental situation in different parts of the country, and the scheme for specific environmental measures in agriculture is organised at municipal level. A considerable proportion of the funding provided through these schemes is allocated to cultural landscape projects. Funding for projects in a set of selected agricultural landscapes and for cultural landscapes that are World Heritage Sites is being used to maintain farming activities and improve coordination of the management and maintenance of some particularly valuable areas. The Government will continue to use both agricultural and environmental policy instruments that encourage use and active management of the agricultural landscape. This helps to counteract the negative trends that are affecting cultural landscapes – overgrowing of open areas with trees and scrub, and abandonment of previously farmed areas. Support for cultural landscape projects under the environmental programmes, selected cultural landscapes and the World Heritage sites will be continued as appropriate.

The Ministry of Transport and Communications will continue its efforts relating to alien organisms by integrating this work into relevant construction, operation and maintenance projects for transport infrastructure. The aim is to prevent alien organisms from becoming a threat to valuable biodiversity.

5.5.6 Mountains

The ecological status of Norway’s mountain ecosystems varies. Land conversion and land-use change (for example the construction of holiday cabins and infrastructure for water and wind power) and climate change are expected to put more pressure on mountain ecosystems in the time ahead. It is particularly mountain areas near Norway’s larger towns that are under pressure, as visitor numbers are increasing and holiday cabins are being built together with access roads and other infrastructure. On the other hand, mountain areas account for a large proportion of the total protected area in Norway. Protected areas and their management are discussed in Chapter 7.

The most important instrument for land-use planning in mountain areas and for ensuring sustainable development outside protected areas up to 2020 is the Planning and Building Act, combined with the principles of environmental law set out in the Nature Diversity Act. The Government expects the Planning and Building Act to be used to ensure sound land-use management and to strike a good balance in cases where there are conflicts of interest in mountain areas generally, and particularly in the buffer zones outside protected areas.

In 2007, to safeguard wild reindeer habitat and ensure sustainable development in mountain areas that support wild reindeer, the Ministry of Climate and Environment set up a programme to draw up regional plans for integrated management of mountain areas that are particularly important for the survival of wild reindeer in Norway (10 national conservation areas have been designated). The Government will use the regional reindeer management plans as a basis for safeguarding wild reindeer and their habitat in connection with development projects and in municipal land-use planning, and to ensure an integrated approach across municipal and county boundaries. The regional management plans must be followed up with action plans and implementation in relevant municipal master plans. We have a sound knowledge of wild reindeer stocks, based on the biology and ecology of wild reindeer, but there is disagreement on the cumulative environmental effects of all projects and developments in wild reindeer habitat. To clarify what the management objectives for species set out in the Nature Diversity Act mean in practice for wild reindeer and identify which developments have positive or negative impacts on wild reindeer, the Government will consider whether to develop a quality norm for the species. Application of a quality norm could also strengthen the common knowledge base for wild reindeer management.

5.5.7 Polar ecosystems

The polar regions are particularly vulnerable to a changing climate, and ecological status in these areas is increasingly being determined by climate change and other external pressures such as ocean acidification and long-range transport of pollution. There is also increasing activity in Svalbard and the northern parts of the Barents Sea. The expansion of activities and industries including research, education, tourism and space-related activity in Svalbard is expected to continue. This is likely to result in more traffic and activity, and create new challenges for the authorities.

Norway’s environmental targets for Svalbard are particularly ambitious. The aim is to retain the extent of wilderness-like areas and maintain the biological and landscape diversity virtually untouched by local human activity. The value of protected areas as reference areas for research will be safeguarded.