9 Responsibilities of local and regional authorities

9.1 Nature as a resource for Norway’s municipalities

Nature itself is one of the most important resources for Norway’s municipalities. It is the basis for human settlement and industrial and commercial activities, provides opportunities for recreation and contributes to people’s sense of identity. Municipalities are showing a growing interest in broad-based value creation based on both natural and cultural resources. The municipalities take all these factors into account in their planning, since this is important in making local communities attractive to business and industry and as places to live. It should therefore be part of the local authorities’ responsibilities to ensure proper management of the natural environment.

9.2 Land-use planning as an instrument for biodiversity management

9.2.1 General application of the Planning and Building Act

The Planning and Building Act provides the municipalities with a very important instrument in their efforts to safeguard Norwegian nature. Together, all the individual decisions made under the Act strongly influence the development of Norwegian society and how successfully biodiversity is safeguarded in both the long term and the short term. Large, robust municipalities with good nature management capacity and expertise can play an effective role in achieving national and international targets relating to biodiversity.

Section 3-1 of the Planning and Building Act requires municipal plans to:

establish goals for the physical, environmental, economic, social and cultural development of municipalities and regions, identify social needs and tasks, and indicate how these tasks can be carried out,

safeguard land resources and landscape qualities and ensure the conservation of valuable landscapes and cultural environments,

protect the natural resource base for the Sami culture, economic activity and way of life,

facilitate value creation and industrial and commercial development,

facilitate good design of the built environment, a good residential environment, a child-friendly environment and good living standards in all parts of the country,

promote public health and counteract social inequalities in health, and help to prevent crime,

incorporate climate change considerations, for example in energy supply, land-use and transport solutions,

strengthen civil protection by reducing the risks of loss of life, injury to health and damage to the environment and important infrastructure, material assets, etc.

A healthy natural environment is essential for achieving most of these purposes, but the degree to which nature and environmental considerations are incorporated into municipal plans varies considerably from one municipality to another. Municipal plans often make it clear which areas should be used for development and commercial activities, but are less specific about areas that should be safeguarded.

Aichi target 2 highlights the importance of integrating the values of biodiversity into local development strategies and planning processes. In Norway, the municipalities play a key role in drawing up such strategies and plans. A good planning process can identify important components of biodiversity in a municipality and areas that are important for connectivity and ecological coherence. Systematic planning can also clarify what additional information is needed about nature in a municipality. A good planning process is one that ensures that residents, interest organisations, the business sector, landowners and others all take part, and where regional and central government authorities also participate and provide guidance from an early stage. Planning processes that integrate biodiversity considerations will make an important contribution to Norway’s achievement of Aichi target 2.

Planning routines for housing developments, industrial development, transport infrastructure and other sectors that also incorporate biodiversity considerations require land-use management based on close cooperation and clear priorities. Preparation of the social and land-use elements of the municipal master plan also gives the municipal authorities the opportunity to consider both land and water areas of the municipality as an integrated whole. The social and the land-use elements of a municipal master plan can both appropriately be used to set overall long-term priorities, including priorities for the conservation of important species and habitats. In addition, the Planning and Building Act’s provisions on zoning plans allow for more detailed specification of how biodiversity is to be safeguarded. The provisions on both the land-use element of the municipal master plan and zoning plans provide for areas to be designated as green structure (nature areas, green corridors, recreation areas and parks); as agricultural areas, areas of natural environment, outdoor recreation areas and/or reindeer husbandry areas; and areas for use or conservation in the sea and river systems and along the shoreline. In the land-use element of a municipal master plan, it is also possible to designate zones where special considerations apply, for example as regards outdoor recreation, the green structure, the landscape, or conservation of the natural or cultural environment – for example in buffer zones around national parks or protected landscapes. The same zones may be designated in the zoning plan, or alternatively, their purpose can be achieved by specifying permissible types of land-use and laying down other appropriate provisions. When processing building applications, the municipality can influence matters such as where buildings are placed on a site, which can be important for biodiversity conservation. Provided that certain conditions are met, municipalities may grant exemptions from the provisions of their plans. This means that the strictness or leniency of the practice they follow when considering exemptions may have implications for trends in ecological status in the ecosystems concerned.

Regional plans are drawn up by the county authorities. They are particularly important for habitats and species whose distribution extends across municipal and county boundaries. The regional approach has for example been used in drawing up plans for the seven national conservation areas for wild reindeer in the mountains in the southern half of Norway. Such plans can contain binding regional planning provisions on land use.

In the case of transport infrastructure projects, the central government transport authorities can reach agreement with the municipal and regional planning authorities to take over part of their normal role in preparing regional and municipal sub-plans and zoning plans. This is set out in section 3-7 of the Planning and Building Act. Transport infrastructure plans are processed and adopted in accordance with the Act’s ordinary provisions. This means that the county authorities normally make decisions on regional sub-plans and the municipalities on municipal sub-plans and zoning plans. However, in the case of major transport infrastructure projects, central government land-use plans may be drawn up instead. In such cases, the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation has the authority to make planning decisions. The Government has indicated that central government land-use plans will be more widely used for large-scale transport projects.

Regional master plans and municipal master plans that include guidelines or set a framework for future developments, and zoning plans that could have substantial effects on the environment and society, must include a description and assessment of the effects of the plan on the environment and society, including its effects on biodiversity. This is required by the regulations on environmental impact assessment for projects under the Planning and Building Act. The purpose is to ensure that the possible impacts of developments are taken into account, and to ensure an open process in which all stakeholders can make their opinions heard. Norway has two sets of regulations on environmental impact assessment, for plans under the Planning and Building Act and for projects under sectoral legislation. Guidelines have been published on recognised methodology, the databases to be used for uploading data, and on Appendix III of the regulations on how to assess whether a project will have significant effects on the environment and society.

Some sectors have drawn up further guidance on environmental impact assessment within their areas of responsibility, as the transport sector has done.

9.2.2 Municipal sub-plans for biodiversity

Land-use conversion and land-use change is the most important driver of biodiversity change in Norway today. It is therefore vital to ensure that there is an integrated planning system in which effects on biodiversity are considered for larger areas and larger numbers of projects and developments at the same time. The land-use element of the municipal master plan is a key part of the long-term basis for municipal planning. It is intended to show how community development is linked to future land use, and how important areas of natural environment will be safeguarded. It is required to indicate both development and conservation needs. Identifying important habitats and ecosystems and analysing their connectivity and ecological coherence is a complex task that requires an overall analysis. It is a challenging task to integrate such analyses into work on a municipal master plan, and as a result there is considerable variation in how fully biodiversity is included in municipal planning processes.

If the overall framework for land-use and community development, including biodiversity considerations, has already been assessed, clarified and incorporated into the municipal master plan, it will be possible to deal with detailed plans for housing developments, commercial activities, infrastructure development and other matters more quickly and predictably. This will benefit local communities, the business sector and other stakeholders. At present, detailed planning processes are in a number of cases delayed by time-consuming conflicts between environmental and other interests. To a large extent, these conflicts should have been resolved during the preparation of municipal master plans. More purposeful work to identify biodiversity values during the preparation of municipal master plans would pave the way for better integrated and more predictable municipal nature management. It would also put the municipalities in a better position to implement their land-use policy.

Section 11-1 of the Planning and Building Act provides for the municipalities to draw up municipal sub-plans for specific topics. Municipal sub-plans for biodiversity, in which biodiversity of local, regional and national importance is identified and taken into account, will provide valuable input for more thorough processes to find a balance between different interests when the land-use element of the municipal master plan is prepared. In the Government’s view, a better framework is needed to encourage municipalities to obtain an overview of biodiversity within their boundaries and identify species and areas that it is important to safeguard, and to do so at an early stage of preparations for the municipal master plan.

Municipal sub-plans for biodiversity would not be legally binding, but their preparation would provide opportunities for broad participation and political discussions about priorities. A biodiversity plan would be adopted through a political process, and would provide guidelines for how biodiversity considerations should be incorporated into the municipal master plan, for example by specifying permissible types of land-use, laying down other appropriate provisions or designating areas where special considerations apply. The county governors would, as they normally do, give the municipalities information on biodiversity and guidance on the best ways of incorporating biodiversity considerations into their plans. There is no provision for making objections to a municipal sub-plan, but in the Government’s view, the planning work would provide good opportunities for dialogue and cooperation between municipalities and county governors at an early stage. This could reduce or prevent conflict and objections at a later stage, during the preparation of municipal master plans.

Under the procedural requirements of the Planning and Building Act, local residents, interest groups, the business sector and others would need to be involved in the planning process for municipal biodiversity plans, thus supporting the goal of strengthening local democracy. The planning process would not only clarify which nationally and regionally important biodiversity municipalities should safeguard, but would also be an opportunity for them to identify locally important biodiversity. Where appropriate, municipalities could also seek to create synergies between biodiversity conservation and safeguarding outdoor recreation areas that are important for local residents. The identification of biodiversity of national importance would also be useful for the central government.

The Government would like to emphasise the importance of leaving it to the municipal councils themselves to decide whether or not to start the preparation of a municipal biodiversity plan. In many cases, it will be easier to draw up the land-use element of the municipal master plan if a biodiversity sub-plan is already in place. Nevertheless, municipalities must be able to incorporate biodiversity considerations directly into the land-use element of the municipal master plan without first preparing up a biodiversity sub-plan if they consider this to be a better approach. There is no question of requiring municipalities to draw up biodiversity sub-plans. However, the Government will encourage municipalities to do so and will take steps to facilitate this approach. The central government could provide financial assistance for the preparation of biodiversity sub-plans as one way of encouraging this.

Municipalities that draw up biodiversity sub-plans will incur costs, but these may be partly offset by efficiency gains in the subsequent planning process. Work on municipal biodiversity sub-plans will also supplement the work being done at central government level on valuing and safeguarding biodiversity and ecosystem services. It will also boost biodiversity expertise in the municipalities. The Government will initiate a pilot project on municipal sub-plans as a biodiversity conservation tool. It may also be appropriate to include other models for incorporating biodiversity into municipal planning processes in the project. The pilot project will be carried out in selected municipalities in 2016 and 2017, and will then be evaluated.

Inter-municipal cooperation on incorporating biodiversity considerations into municipal planning processes would be useful. It would allow close coordination across municipal boundaries. This would benefit biodiversity directly and could also be important in ensuring the smooth running of road construction projects and other major infrastructure projects.

The Government will:

Initiate a pilot project on the use of municipal sub-plans as a biodiversity conservation tool.

9.3 Municipal capacity, expertise and commitment

The municipalities must have sufficient administrative capacity, sound scientific expertise in nature management, knowledge about biodiversity in the municipality and adequate management expertise to be able to draw up good plans that ensure sustainable management and land use and prevent the loss of biodiversity. An Official Norwegian Report (NOU 2013:10) on the values related to ecosystem services highlights the crucial importance of strengthening the expertise of the municipal sector to ensure sound management of ecosystems and ecosystem services.

If municipalities are actively involved in biodiversity conservation, public interest and engagement may also be stimulated. This in turn can help to keep biodiversity on the municipal policy agenda over time. But this kind of positive feedback only works if municipal politicians, the local administration and residents all feel a sense of ownership of the biodiversity values that need to be safeguarded. In this context, the Government would like to emphasise that it is up to the municipalities themselves to define which areas, species and habitats it is particularly important to safeguard at local level. The municipalities must register and map such areas as a basis for including them in biodiversity sub-plans, see Chapter 9.2.2. This work will be an important supplement to the conservation of areas of national importance, as described in Chapters 6 and 7. The Government will consider more closely how registration and mapping of locally important areas, species and habitats should be organised.

The Directorate for Cultural Heritage is currently running a programme to modernise cultural heritage management and make it more effective. For this to be successful, it is essential to build up cultural heritage expertise in the municipalities. The Directorate has drawn up guidelines to assist the municipalities in drawing up cultural heritage sub-plans. The Government will consider whether elements of this programme are also applicable to efforts to build up municipal expertise and engagement on biodiversity. The Government is also seeking to simplify the administrative system for uncultivated areas.

The Government has also initiated a reform of local and regional government, which is intended to result in more robust municipalities with the necessary scientific expertise and capacity. The Government’s efforts to build up knowledge about nature and make this available will provide a vital basis for continued municipal work on biodiversity in the planning context, see Chapter 8.

The Government will:

Ensure that there is adequate scientific expertise in nature management in the municipalities.

9.4 The municipal revenue system

National parks and other protected areas are established to safeguard national interests and meet international obligations. They can be seen as public goods of substantial value, but the municipalities that are directly affected only benefit from them to a limited extent. Revenue from nature-based tourism, for example, does benefit the municipalities, but the overall national value derived from these areas may be much greater than this. And although protected areas do have a value for local communities, the way they can be used is restricted, and this may entail a risk of the loss of municipal revenue: protection may hamper the development of commercial activities in protected areas. The municipalities do not receive any financial compensation for these potential losses, although they take the risk on behalf of the nation as a whole. This situation has been highlighted by two Official Norwegian Reports, NOU 2009:16 on global environmental problems and Norwegian policy, and NOU 2013:10 on the values related to ecosystem services. Both reports recommended changes so that there is better harmony between responsibilities and incentives. In NOU 2013:10, one of the recommendations is to carry out a review of a system of economic incentives for municipalities to safeguard biodiversity and ecosystem services. The report also recommends reconsidering whether to use a model that includes a municipality’s environmental efforts and performance as criteria when block grants are allocated.

In principle, block grants are intended to allocate funding to the municipalities on the basis of their real needs in terms of expenses, using criteria that the municipalities themselves have no control over. Rewarding actual environmental efforts and/or performance would therefore be in conflict with the principles for awarding block grants. A criterion based on the total protected area in a municipality would be technically possible to use, and this is determined by central government decisions, not by municipal decisions. However, this criterion would reflect a potential loss of revenue, not necessary expenses, and there is little reason to assume that a possible loss of revenue is proportional to the area protected. Moreover, protected areas may also offer opportunities for value creation in municipalities, as mentioned earlier, and this can be difficult to include in the calculations. This issue has already been discussed in the 2011 proposition to the Storting on local government, and the Government maintains its position that this should not be included in the set of criteria for allocating block grants to the municipalities.

9.5 Guidance on integrating biodiversity into planning processes

The municipalities are required to take overall central government and regional interests into account in their planning. New official Government expectations for regional and municipal planning were adopted by royal decree on 12 June 2015. The county and municipal councils must use them as a basis for work on regional and municipal planning strategies and plans, and they also apply to central government participation in these planning processes. The Government expectations highlight the importance of identifying and safeguarding important species, habitats and ecosystem services.

Section 11-1, second paragraph, of the Planning and Building Act makes it clear that municipal master plans must take municipal, regional and central government interests into account. Moreover, the objects clause of the Local Government Act requires arrangements to be made for rational and effective administration of common municipal and county interests within the overall framework of Norwegian society and with a view to sustainable development.

The Government considers it important that the municipalities have a considerable degree of freedom to set land-use management priorities. At the same time, there are many divergent and sometimes conflicting interests that must be identified and weighed up against each other during planning processes. The central government administration must clarify which components of biodiversity are of national or regional value and must therefore be given special consideration, and must provide the best possible knowledge base on biodiversity for use in municipal land-use planning. It is also a central government responsibility to provide guidance with a view to moderating the cumulative environmental effects of human activity. Documents that have been produced relating to the Planning and Building Act include guidelines on planning the green structure in towns and built-up areas and on planning holiday housing.

To ensure that national and significant regional interests are taken into account, relevant central government and regional bodies and the Sámediggi (Sami parliament) are entitled to raise objections to drafts of the land-use element of municipal master plans or zoning plans. Other municipalities that are affected may also raise objections if the issues involved are of significance to them. The right to put forward objections is contingent on a preceding administrative process allowing real participation by and cooperation between the sectoral authorities, the county and the municipality. To prevent unnecessarily large numbers of objections concerning biodiversity, the Government considers it important for the county governor to provide information and advice on valuable biodiversity in the municipalities involved at the earliest possible stage of planning processes. A good dialogue between the county governor and the municipalities will be conducive to land-use planning that strikes a satisfactory balance between biodiversity interests and other public interests.

The Government wishes to strengthen local democracy, reduce the number of objections to plans and facilitate a greater degree of local adaptation of land-use policy. Its main approach is to encourage more use of thematic municipal sub-plans, is intended to make it easier for the municipalities to incorporate biodiversity conservation into planning processes. To give the municipalities a more predictable framework, the Government will draw up better guidance documents that clarify how they are expected to include biodiversity considerations in their planning activities. In this connection, the Government will also review existing guidance material with a view to improving and simplifying the documents. Revision of the guidelines for planning in coastal waters has already been started.

Climate change adaptation is becoming a particularly important task for the municipalities. The ecosystem services provided by nature can play a major role in climate change adaptation, particularly regulating services such as natural flood control, water purification and protection against erosion. Another factor that must be taken into consideration in connection with climate change is whether special measures will be needed for habitat types that may be particularly seriously affected by climate change. The municipalities will have a substantial need for advice in this field in the time ahead.

The Government will:

Continue to develop guidance material for municipalities on how to integrate biodiversity conservation into their activities.

Develop guidance material for municipalities on how they can make use of ecosystem services in their climate change adaptation work.

9.6 Biodiversity in towns and built-up areas

Many towns and built-up areas in Norway are in or near productive areas in the lowlands and along the coast, which have always been attractive areas for human settlement. Biodiversity was originally very high in these areas, and they still contain patches of natural habitat and habitats used by many threatened and other species. Connections between the different green spaces in towns and other built-up areas make it possible for many species to move between them, thus promoting the spread of biodiversity and genetic diversity. Green spaces are also important because they give people opportunities for enjoying the outdoors and outdoor recreation and play. At the same time, there is constant pressure to allow development of these areas. In built-up areas, artificial habitats can often function as substitute biotopes for species in built-up areas. Innovative examples of this include green roofs and walls.

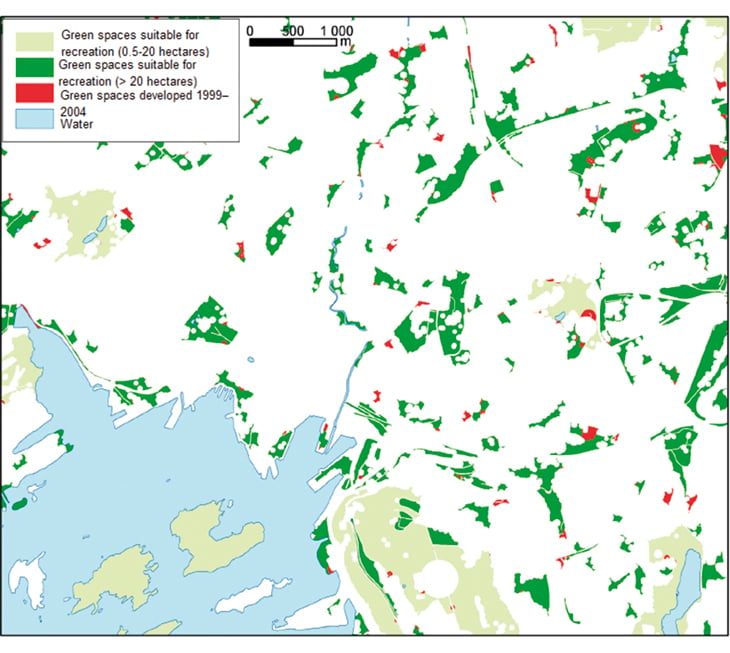

Figure 9.1 Green spaces in Oslo

Green spaces in Oslo and areas lost in the period 1999–2004

Source Engelien with more 2005

Some towns have begun to restore areas of natural habitat. This can be encouraged through urban planning and development processes. A number of culverted rivers and streams have been re-opened so that they form part of the green structure.

Although towns and built-up areas are heavily modified ecosystems, there is considerable potential for retaining areas within them that are of importance for biodiversity. Safeguarding the environment also has positive effects on people’s well-being and the quality of their lives.

Green spaces in towns and built-up areas are under pressure, and the total area of such spaces is declining. At the same time, many threatened species and habitats are found in and around urban areas. The Government therefore considers it important that existing instruments, particularly the Planning and Building Act, are used to safeguard biodiversity in towns and built-up areas, and that the municipalities receive sound guidance on how to do this.

Many outdoor recreation areas in and near towns and built-up areas are also valuable for biodiversity. Work in the outdoor recreation sector is therefore also important for biodiversity conservation in towns. Two examples of initiatives that are relevant in this connection are the national strategy for outdoor recreation and a programme run by the Norwegian Environment Agency to encourage more physical activity, especially by children and young people, and to safeguard more outdoor recreation areas near people’s homes.

The Government considers it important to give priority to biodiversity conservation in towns and built-up areas. One approach that can be useful is cooperation between private- and public-sector landowners in developing and managing green spaces of various types and sizes. Programmes such as the initiative for development of the Groruddalen area of eastern Oslo, which involves cooperation between the City of Oslo and the Government, are valuable for the area involved. They also provide opportunities for exchanging information with other towns and for developing examples of good practice. The first ten-year period of the Groruddalen initiative is coming to an end, and it will be continued for another ten years from 2017. Local community development will be one of the three main themes from 2017. This will include developing green spaces and waterways near residential areas, which will also play a part in the conservation of urban biodiversity.