4 Objectives, policy instruments, administration

4.1 Key objectives

The objectives of the Svalbard policy have remained unchanged for a long time, and have been articulated in Report No. 40 (1985–1986) to the Storting Svalbard (see Recommendation to the Storting No. 212 (1986–1987); Report No. 9 (1999–2000) to the Storting Svalbard (see also Recommendation to the Storting No. 196 (1999–2000)); and Report No. 22 (2008–2009) to the Storting Svalbard (see Recommendation to the Storting No. 336 (2008–2009)). These objectives have been reiterated in subsequent Storting documents relating to Svalbard and are reaffirmed annually when the Svalbard budget is approved. The Government’s overriding objectives for the Svalbard policy are:

Consistent and firm enforcement of sovereignty

Proper observance to the Svalbard Treaty and control to ensure compliance with the Treaty

Maintenance of peace and stability in the area

Preservation of the area’s distinctive natural wilderness

Maintenance of Norwegian communities in the archipelago

There is broad political consensus across party lines on the objectives of the Svalbard policy. This was confirmed by the Storting’s consideration of Report No. 22 (2008–2009) to the Storting Svalbard, and is also reflected in its consideration of the annual Svalbard budgets.

The Government attaches importance to continuity and predictability in the administration of the archipelago, and will therefore continue to pursue the overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy. Continued predictability in the administration of Svalbard in line with these objectives provides security for the population of Longyearbyen while enhancing stability and predictability in the region.

For a more detailed account of the overriding objectives, reference is made to Report No. 22 (2008–2009) to the Storting Svalbard and to the respective chapters in this white paper.

4.2 Policy instruments

By virtue of Norway’s sovereignty over the archipelago, the authorities have access to the same policy instruments that are available in the rest of Norway. The central government’s key social development policy instruments are: legislation, economic policy instruments and various forms of ownership. Participation in committees or organisations can also constitute policy instruments. Specific to Svalbard in this respect is the coordination of Svalbard affairs within the central government administration through the Interministerial Committee on the Polar Regions. In addition, a separate budget proposition (the Svalbard budget) is presented simultaneously with the national budget. These policy instruments are discussed in more detail below.

How, and to what degree, these policy instruments are used depends on whether the economic climate is characterised by continued, self-driven development or whether particular forms of stimulus are desired. At all times, the framework for their use is proper compliance with the Svalbard Treaty and the overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy. Development in the past decade has been largely of the self-driven variety. In such a situation, the primary task of the authorities is to provide for necessary regulation to ensure that development does not conflict with the overriding objectives as a whole. Since the previous white paper on Svalbard was presented, a growing number of laws and regulations concerning Svalbard have been implemented, ensuring that the activities pursued in the archipelago accord with Norwegian law.

As described in the introduction, this white paper pays particular attention to the objective of maintaining Norwegian communities in the archipelago. This objective is pursued through the family community policy in Longyearbyen. Continued development of existing activities such as tourism, research and higher education will contribute to this. However, it is also important to facilitate broader, more diversified economic activity.

Both economic activity and research and higher education activity are most likely to succeed in cases where they build upon on Svalbard’s inherent natural conditions. Facilitating economic activity, particularly tourism, stands out as one of several measures that can contribute to achieving this objective. However, the central government is not a tourism industry actor, and the authorities will also have other considerations in mind, as illustrated by the five overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy. In order to facilitate economic activity, the Storting has approved this Government’s proposal to allocate NOK 20 million to Innovation Norway. This appropriation enables businesses to apply for start-up grants or funding to develop different initiatives.

The scope of research and higher education in Svalbard has doubled during the past decade, making these areas an important part of Norwegian activity in the archipelago. Longyearbyen has strengthened its position as a hub for research and higher education, both of which form much of the foundation for the local community.

This white paper describes the Government’s ambitions for Svalbard, and in doing so provides guidelines for the archipelago’s further development. It is important that the administration take these into consideration in its work.

The Longyearbyen Community Council was established in 2002 and must, according to its statement of purpose, ensure ‘a rational and effective administration of common interests within the framework of Norwegian Svalbard policy’. According to the provision, the Longyearbyen Community Council has an important task with regard to achieving national objectives. Of particular note is the council’s role as local facilitator, helping to increase and diversify economic activity in accordance with the guidelines of this white paper.

4.2.1 Legislation

Legislation is the most important policy instrument for Norway’s exercise of authority in Svalbard and for advancing its other Svalbard policy objectives. See Chapter 5, ‘Legislation’, for a more detailed discussion of legislation as a policy instrument and of the legislative situation in specific areas. Important regulations in different areas are also discussed in more detail in Chapter 7, ‘Environmental protection’; Chapter 9, ‘Economic activity’; and Chapter 10, ‘Civil protection, rescue and emergency preparedness’.

4.2.2 State ownership in companies and real property

The Norwegian state owns the mining company Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani AS (SNSK), Kings Bay AS, Bjørnøen AS and the University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS), all of them as state-owned limited companies. The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries today manages the state’s shares in SNSK, Kings Bay AS and Bjørnøen AS, while the Ministry of Education and Research manages the state’s ownership in UNIS. Furthermore, Svalbard Satellite Station (SvalSat) is owned by Kongsberg Satellite Services (KSAT), a company in which the state has an indirect ownership interest through its ownership interest in Space Norway and Kongsberg Gruppen.

State ownership in companies in Svalbard

The Norwegian state owns, either directly or indirectly, several companies in Svalbard. The objective of state ownership of companies in Svalbard is to contribute to maintaining and further developing the community in Longyearbyen in a way that supports the overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy.

The SNSK group is a state-owned company. The group currently consists of the parent company, Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani AS (SNSK), and the wholly owned subsidiaries Store Norske Spitsbergen Grubekompani AS (SNSG) and Store Norske Boliger (SNB). SNSK owns approximately 380 housing units through Store Norske Boliger AS. SNSK also owns 65 per cent of the shares in the subsidiary Pole Position Logistics AS. SNSK’s head office is located in Longyearbyen. The SNSK group is also the largest claim holder in Svalbard, with 324 claims.

During almost 100 years of operation, SNSK has supported the Longyearbyen both directly and indirectly. In recent years the company has been classified as a Category 3 company according to the definition given in Report No. 27 (2013–2014) to the Storting Diverse and Value-Creating Ownership. Companies in this category compete with other businesses on a commercial basis. At the same time, the objective of state ownership in SNSK is to contribute to maintaining and further developing Longyearbyen in a way that supports the overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy. The state’s ownership objective is met through its ownership role in the company, and not by issuing special guidelines for company operations.

SNSK has played, and will continue to play, an important role in the Longyearbyen by supplying coal to the power plant. The company’s recent performance has provided cause to reconsider its categorisation. To better reflect the various issues the state must consider as owner of SNSK, the Government announced in Proposition to the Storting No. 52 S (2015–2016) that SNSK’s categorisation would be changed from Category 3 to Category 4. Category 4 includes companies with sectoral policy objectives. Report No. 27 (2013–2014) to the Storting Diverse and Value-Creating Ownership states that the objective for this type of company should be adapted to the purpose of ownership. As owner, the state will place emphasis on the achievement of sectoral policy objectives as effectively as possible. The company and its further development are discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.

Kings Bay AS is a state-owned company. Kings Bay owns land and most of the buildings in Ny-Ålesund. Kings Bay AS provides services in Ny-Ålesund to facilitate research and scientific activity, and contributes to developing Ny-Ålesund as a Norwegian centre of international Arctic scientific research. Today the company receives subsidies for investments from the central government budget, and plays a key role in achieving the objective of further developing Svalbard and Ny-Ålesund as a platform for international polar research. The company also administers many cultural heritage sites in Ny-Ålesund and in the surrounding land area measuring 295 km2.

The business purpose of Bjørnøen AS is to manage and utilise the company’s property in Svalbard, and other related activities. Bjørnøen owns all the land and some historically significant buildings in Bjørnøya. The company is administratively organised under Kings Bay AS. The objective of state ownership in Bjørnøen AS is to manage property holdings on Bjørnøya. The company’s operations must be effective.

SvalSat is owned by Kongsberg Satellite Services (KSAT). In turn, 50 per cent of KSAT is owned by Space Norway (which is wholly owned by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries) and 50 per cent by Kongsberg Gruppen, in which the state has a 50-per-cent stake. The station in Svalbard is the northernmost in the world for downlinking satellite data, and currently has 16 employees and an annual turnover of more than NOK 100 million. SvalSat is a global leader in downlinking data from weather satellites in polar orbit. State ownership in KSAT contributes indirectly to ensuring that SvalSat is managed in line with the overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy, and affords control to ensure that the nature of its activities does not change without that being the intention.

State ownership of land in Svalbard

The Norwegian state owns approximately 98.4 per cent of all land in Svalbard. Through its ownership in Kings Bay AS and Bjørnøen AS, the state indirectly owns a further 0.75 per cent of land in Svalbard. In 2015 the state purchased land in Svalbard from SNSK.

In addition to land, the state owns infrastructure and building stock related to Mine 7 in Adventdalen, in Svea, and in Lunckefjell, as well as some infrastructure and building stock in Longyearbyen. The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries owns the state’s real property in Svalbard. Parallel with the transfer of the land to the state in 2015, a rental and management agreement was signed with SNSK under which the company rents and manages the real property on behalf of the Norwegian state.

The state-owned properties in Svalbard are managed in line with the overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy. Through its ownership of the land in Longyearbyen, the state will, in consultation with the Longyearbyen Community Council as the planning authority, facilitate business and urban development within the scope of the objectives of the Svalbard policy. In the time ahead, the Government will consider how the building stock and infrastructure in Svea should be further managed pending a possible decision to discontinue mining operations.

Table 4.1 Summary of distribution of land ownership in Svalbard, by percentage of land area

Landowner | Percentage of land area |

|---|---|

Norwegian state | 98.4 per cent |

Kings Bay AS | 0.47 per cent (Kings Bay) |

Bjørnøen AS | 0.28 per cent (Bjørnøya) |

Trust Arktikugol | 0.4 per cent (Barentsburg and Pyramiden, etc.) |

AS Kulspids | 0.1 per cent (Søre Fagerfjord) |

Horn family | 0.35 per cent (Austre Adventfjord) |

4.2.3 The Svalbard budget

Every year government funding is allocated for a variety of purposes in Svalbard, drawing on the Svalbard budget and on central government budget chapters pertaining to various sectoral ministries. The Ministry of Justice and Public Security presents the Svalbard budget as a separate budget proposition concurrently with the central government budget proposal. A separate budget for Svalbard is presented every year in order to show the revenues and expenditures in Svalbard. The budget gives an overall view of the Government’s focus areas and priorities in Svalbard. Report No. 22 (2008–2009) to the Storting, Svalbard states that the Ministry of Justice and the Police ‘will consider a closer examination of the content of some of the chapters of the budget to ensure that appropriations harmonise in the best possible way with the objectives of the various chapters’. In pursuance of this, budget chapter 2, ‘Subsidies for cultural purposes etc.’, has been discontinued and the resources transferred to other chapters. Furthermore, the following three budget chapters have been added: chapter 4, ‘Subsidies to Svalbard Museum’; chapter 3020, ‘Statsbygg, Svalbard’; and chapter 3022, ‘Tax Office, Svalbard’. In addition, some chapter titles have been updated. Combined, these revisions have helped give a more accurate description of the various allocations from the Svalbard budget.

Tax revenues in Svalbard have varied considerably during the period since the previous white paper was published (Report No. 22 (2008–2009) to the Storting Svalbard); see Table 4.2. This is due primarily to large tax revenues from profits by the rig operator Seadrill Norge AS and SNSK. The decline in revenues in financial year 2014 was due to an adjustment to the tax assessment for Seadrill Norge AS. After final settlement, it was decided that revenues previously taxed under Svalbard tax rules for the financial years 2008–2012 should be reassessed under ordinary tax rules.

Still, expenditure from the Svalbard budget during that period shows an increase, reflecting the general rise in activity in the archipelago during that period as well as government investment in Svalbard and the High North.

Table 4.2 Overview of Svalbard budget trends, based on accounting figures 2008–2014

(NOK million) | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Revenues | 134 | 539 | 349 | 816 | 540 | 151 | -1 058 |

Subsidies | 96 | -298 | -95 | -544 | -240 | 176 | 1 512 |

Expenditure | 230 | 241 | 254 | 272 | 300 | 328 | 455 |

Source Meld. St. 3 Central government accounts including National Insurance for 2008–2014

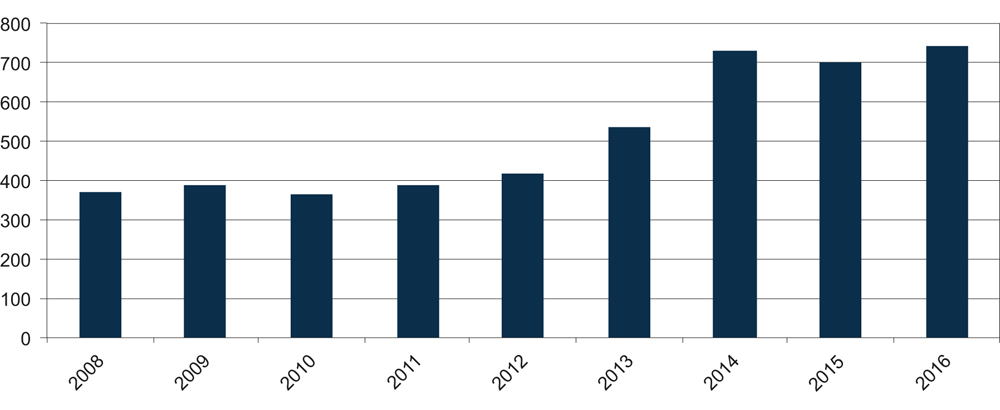

Figure 4.1 shows total appropriations for Svalbard purposes from the central government budget during the period. The reason for the increase shown here is the same as that given above: increased investment in Svalbard and the High North. The increase during this period is closely linked to the rehabilitation of the energy supply system in Longyearbyen and the signing of new rental contracts for helicopters and service vehicles by the Governor of Svalbard in 2014.

Figure 4.1 Total appropriations from the central government budget for Svalbard purposes, in NOK million.

Proposition 1 S to the Storting, Svalbard budget, from 2008 to 2016

The Svalbard budget gives the Storting an overall presentation of the Government’s investments and priorities in Svalbard. The Svalbard budget also provides the opportunity for annual presentation of developments in the archipelago. At a time when economic activity stimulus in Longyearbyen is welcome, the Svalbard budget is a policy instrument the central government can use to help achieve development towards this objective in line with the overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy. For these reasons, the Government will continue the system of presenting a separate budget for Svalbard.

4.2.4 Administration

As in the rest of Norway, the management and administration of Svalbard have changed over time. Previously the general rule was that central authorities had overriding and direct control over most of the Norwegian activities in the archipelago. In step with new developments elsewhere, this situation has gradually changed, with the result that the management aspect is now more decentralised. This development is part of a deliberate policy tailored to the situation. The situation for Longyearbyen is therefore closely related to the fact that the scope and diversity of economic activity have increased compared with previous periods.

Developments in recent years also show that the coordination of Svalbard affairs is becoming increasingly complex. There are a number of reasons for this, including in particular Longyearbyen’s recent growth, the increase in private economic activity, and more extensive field activity (especially in tourism and research). Although these developments have resulted in a gradual reduction in special administrative treatment for Svalbard beyond where this is necessary, there is still a need to view some Svalbard issues using a comprehensive, overall perspective. Therefore, the decentralisation of authority also entails a specific need to coordinate between the responsible authorities.

The growth in activity in Svalbard has meant that more laws are now made applicable to the archipelago, and several ministries now play a role in formulating the Svalbard policy than was the case a few decades ago. At the same time, Longyearbyen now has more diversified economic activity and a more complex constellation of actors that influence developments locally. The Longyearbyen Community Council has established its position as the local authority and administrative body; dialogue with the ministries is important to ensure that Longyearbyen’s community development conforms with the overriding objectives of the Svalbard policy. The Ministry of Justice and Public Security and the Longyearbyen Community Council maintain regular dialogue.

Central administration

The Ministry of Justice and Public Security has responsibility for coordinating polar affairs in public administration. One of the ministry’s key policy instruments in this regard is the Interministerial Committee on the Polar Regions. The committee convenes about 10 times a year and performs its work in accordance with specific instructions first laid down by the Royal Decree of 6 January 1965. The committee’s mandate and composition were strengthened by the Royal Decree of 18 October 2002. The Interministerial Committee on the Polar Regions is a coordinating and consultative body for the central administration’s handling of polar affairs, and serves as a special advisory body to the Government on such matters. The fact that polar matters are submitted to the Interministerial Committee on the Polar Regions changes neither the decision-making authority of the relevant ministry nor the relevant minister’s constitutional responsibility for decisions made.

Another important tool for the central administration is the Svalbard budget, which is presented annually as a proposition by the Ministry of Justice and Public Security; see the discussion of the Svalbard budget above.

Figure 4.2 The Governor of Svalbard’s administration building.

Photo: Frode Schärer Bjørshol, Ministry of Justice and Public Security

The Governor of Svalbard

The Governor of Svalbard is the Government’s highest-ranking representative in the archipelago, and serves as both chief of police and county governor. As chief of police, the Governor of Svalbard has the same responsibilities and authority as chiefs of police on the mainland. The Governor has responsibility for the rescue services and also for community preparedness. The main tasks in these areas of responsibility consist of rescue and emergency preparedness, police duties and public prosecution. See Chapter 10, ‘Civil protection, rescue and emergency preparedness’, for a more detailed discussion of rescue and emergency preparedness tasks in Svalbard.

As county governor, the Governor of Svalbard acts as the regional state environmental authority in Svalbard, and is responsible for enforcing environmental legislation and monitoring compliance. The Governor’s environmental protection duties cover a broad spectrum, including protected areas, species management, cultural heritage, encroachment and pollution. Planning activities not designated as the responsibility of the Longyearbyen Community Council come in addition. Case preparation, application processing, regulatory duties and development of management plans are other important tasks of the Governor in the area of environmental protection. See Chapter 7, ‘Environmental protection’, for a more detailed discussion of the environmental tasks in Svalbard.

The Governor of Svalbard is also an important adviser on the formation of the Svalbard policy.

To enable the Governor of Svalbard to resolve new challenges relating to rescue and emergency preparedness, the police manpower has been strengthened and a new annex to the administration building has been built to house a new operations room. The environmental department has also allocated more positions.

All these investments make the Governor of Svalbard well equipped to resolve current tasks in a satisfactory manner. If the Governor is assigned new tasks and responsibilities, there will be further need to strengthen manpower levels.

Longyearbyen Community Council

The Longyearbyen Community Council (LCC) was appointed in 2002 and has become an important partner for the central authorities. The council works to ensure environmentally responsible and sustainable community development in Longyearbyen that complies with the wishes and needs of the local population and is within the framework of the Svalbard policy. The LCC receives most of its operating funds via a block grant from the Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Some guidelines are issued to the council by the central authorities through letters of allocation and contact with the ministry.

The establishment of the LCC has provided a more up-to-date form of exercising of authority at local level. The council has management responsibility for specific areas within the Longyearbyen land-use planning area. In many areas its tasks are similar to those of a mainland municipality. LCC also has responsibility for energy supply, however. On the other hand, it has no tasks or expenditure for elderly care because Longyearbyen is not a cradle-to-grave community. Nor does the council have any responsibility for expenditure for other health and care services; see section 6.3.3.

Supplying energy in the form of both heat and electricity is one of the LCC’s most important tasks, as well as one of the most expensive. To secure operations and extend the lifetime of the power plant, extensive maintenance and upgrading work has begun. The state covers two-thirds of the cost of this work. The upgrade is expected to extend the lifetime of the power plant by 20 to 25 years from when the work began in 2013. Between 2012 and 2014 funding was allocated to build a sewage treatment plant to deal with emissions of sulphur and particulates from the power plant, among other things.

Operation of the power plant is currently based on coal from Mine 7. The long-term supply of coal from this mine may be affected by the changes in the production plans for Mine 7.

See section 6.2.3 for a more detailed discussion of energy supply.

Other government agencies etc.

The Norwegian Polar Institute is a directorate under the Ministry of Climate and Environment, and is the central government institution for mapping, environmental monitoring and management-related research in Arctic regions. The Norwegian Polar Institute has a permanent presence in Longyearbyen as advisory body to the Governor of Svalbard, among other things. The Directorate of Mining, with the Commissioner of Mines at Svalbard, has its own office and staff in Svalbard. The directorate administers the Mining Code for Svalbard. The tax office in Svalbard is established in Longyearbyen, and Statsbygg Svalbard has its office there, too.

Avinor is a state-owned limited company, and Longyearbyen Hospital is part of the University Hospital of North Norway and as such is state-owned; see the Health Authorities and Health Trusts Act. Svalbard Church is now a public agency in Svalbard. It has been proposed that the agency be separated from the state and transferred to the Church of Norway, in line with the proposal to establish the Church of Norway as an independent legal entity, separate of the state; see Proposition to the Storting No. 55 L (2015–2016) to amend the Church of Norway Act.

Textbox 4.1 Management of tourism, field trips and other travel activity in Svalbard

The Governor of Svalbard processes cases pursuant to the Regulations of 18 October 1991 No. 671 relating to tourism, field trips and other travel in Svalbard. These regulations have two purposes. One is to ensure that everyone who travels around Svalbard take safety into account when planning and carrying out field trips. The duties to provide notice of activity and to carry insurance are important in this connection. The tourism regulations are also intended to safeguard the interests of the natural environment and cultural monuments. In this respect, the regulations align with the provisions in the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act regarding behaviour in the field.

The tourism regulations were recently revised, and the resulting amendments entered into force on 8 January 2015. This revision was performed after close dialogue between the Governor of Svalbard and the tourist industry in Svalbard, among others.

On completion of the revision process it was concluded that there was no need to create a mandatory certification scheme for guides. This matter was looked into as a follow-up to the Storting’s consideration of the previous white paper on Svalbard; see Recommendation to the Storting No. 336 (2008–2009), in which this matter was raised. In extension of this follow-up, new provisions were introduced setting requirements for the qualifications of tour operators in Svalbard. Another new provision was introduced assuring the Governor of Svalbard access to documentation needed in exercising official tasks pursuant to the regulations. A new administrative sanction was also introduced giving the Governor of Svalbard authority in certain circumstances to postpone tour operators’ right to submit notice of planned tours.

Safety and environmental considerations apply regardless of who travels around Svalbard. This was made explicit in a new provision stipulating that representatives from research and educational institutions were also subject to the tourism regulations when travelling in the field.

The Governor’s tourism adviser has prime responsibility for administering the tourism regulations, as well as for liaising between the tourism industry and the Governor of Svalbard. This channel of communication serves as a good tool for exchanging information, providing guidance, and discussing issues that either party may wish to raise. The tourism regulations have been in force since 1992, and experience has proven them a useful tool in a growing, dynamic tourism market.