2 Background and analysis

Norway has been engaged in development cooperation since the 1950s. There is broad agreement among the population that Norway should use some of its wealth to promote development in poor countries. Norwegian development cooperation and international development policy has thus been characterised by continuity. Norway’s policy is based on values such as solidarity and compassion, and a fundamental belief in the right of all people to a dignified life. World poverty is an affront to human dignity, and is often caused by violations of other fundamental human rights.

Traditionally, Norway’s development cooperation has been based on a sense of own obligation and needs –based in the South. In recent years however, this approach has come under pressure. International development policy and cooperation are no longer primarily a matter of solidarity or altruism, but are increasingly regarded as being in our own interests. In this age of globalisation, it is evident that living conditions in developing countries also affect people in the rich part of the world. We must reap the benefits offered by globalisation, for example as regards migration, development policy, democracy and energy security; but we must also manage the risks it entails, such as human trafficking, the spread of HIV and AIDS, conflict and climate change. In giving priority to these areas in our international development policy, we are therefore also giving priority to matters that concern us directly. These areas are also linked to lack of development, poverty and marginalisation. Lack of development is thus inextricably linked to a lack of stability, security and environmental sustainability, at local, national and global levels.

In this perspective, it is thus also in Norway’s and other donors’ interests to engage in development cooperation. Many would claim that international development policy is also ultimately part of the policies of globalisation, migration and security. This is a policy approach that is consistent with other areas of Norwegian policy. In the Government’s view, Norway has an enlightened self-interest that does not conflict with developing countries’ own interests.

There is also general agreement as regards the choice of international development actors. Norway is a firm supporter of the UN and the multilateral system, where the international financial institutions play a key role. Civil society actors in Norway, particularly NGOs, play an important role in Norwegian development cooperation, as do civil society actors in our partner countries, in addition to the authorities.

2.1 Considerable variation and scope

We must take care not to oversimplify reality. It is easy to view the world in black-and-white terms, contrasting the egalitarian, rich part of the world with the poor part of the world where women and sexual minorities are oppressed. But the picture is far more complex than that. There are poor countries that have made great progress in terms of gender equality, and there are rich countries that have made very little. The underlying causes of gender inequality vary from country to country. This is why we need both a sound knowledge of the global situation and access to expertise on the particular situation in each partner country. We must identify and support relevant agents of change and tailor our approach and efforts to local conditions. If we fail to do so, there is a danger that our efforts will be in vain, or, at worst, counterproductive.

Textbox 2.1 Equal access to education

According to Article 10 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to ensure that women have the same rights as men in the field of education, including the same conditions for career and vocational guidance, for access to studies and for the achievement of diplomas.

The progress reports on the implementation of the Millennium Development Goals present the status for women and men in different parts of the world. They include data for both sexes as regards education, participation in political and economic processes and health targets such as the use of contraception and the incidence of AIDS. The MDG indicators do not measure other gender disparities, for example regarding income and life expectancy. It is therefore necessary to consult other sources to get a full picture of how progress towards gender equality varies between countries and regions. NGOs and various parts of the UN system are doing important work gathering such data.

Every year the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) ranks the countries of the world according to their success in ensuring longevity, basic education and a decent standard of living for their populations. Human development indexes are drawn up both for the population as a whole and for women compared with men. These comparisons show clearly that the position of women in a particular country cannot be deduced from the country’s general level of development. Knowledge of the country’s politics and traditions is important in order to understand the status of women’s rights. Pakistan, for example, scores higher than Bangladesh as regards general development, but the reverse is the case as regards the situation of women. This is because women in Bangladesh have a higher level of literacy and earn more than Pakistani women. In many Arab countries, women are lagging behind in development, and these countries score lower on the gender-equality index than on the general human development index. Other countries, such as Sri Lanka, Namibia, Uganda and Kenya, rank higher on the gender equality index than on the general human development index. In Oman, women’s purchasing power is less than one fifth of men’s; in Burundi women earn less than 80 % of what men earn. In countries like Nicaragua and Honduras, the literacy rate is approximately the same for women and men. In Yemen and Guinea, on the other hand, illiteracy is more than twice as high among women as it is among men.

The World Economic Forum, which arranges annual meetings in Davos, also draws up a comprehensive report, The Global Gender Gap Report, on women’s participation in four different areas: economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival and political empowerment. The report compared the status of gender equality in 115 countries in 2006, both in general and in each of the four areas.

Not surprisingly, the Nordic countries topped the list in 2006, with Sweden coming first, closely followed by Norway. These two countries score highest on political empowerment, but lower on health and survival. It is interesting to note that a poor country like the Philippines ranks sixth, with top scores in both health and education. Another poor country, Sri Lanka, scores high on gender equality, ranking thirteenth overall. It occupies first place as regards health and survival and seventh place as regards women’s political empowerment. Tanzania, which ranks 24th overall, has a first place as regards women’s economic participation. However it ranks 97th and 95th on education and health, respectively, which is what pulled its overall score down.

Textbox 2.2 Equal access to health services

Article 12 of CEDAW requires the States Parties to ensure, on the basis of equality of men and women, access to health care services, including those related to family planning, and appropriate services in connection with pregnancy, confinement and the post-natal period, granting free services where necessary.

Japan, which is a rich country, ranks 79th. Even with a first place on health and survival, a scoring it shares incidentally with Cambodia among others, its overall ranking is low, as it scores 83rd on economic participation and opportunity, 59th on educational attainment, and 83rd on political empowerment. Another rich country, Cyprus, ranks 83rd, just behind Malawi. Yemen and Saudi Arabia rank last and second-to-last in this index.

This report is a useful practical tool because the areas it analyses largely correspond to our own main priority areas. Equally important, the report shows that we are facing a multifaceted, complex situation that we need to address in our international development policy. The figures indicate that there are considerable variations; poverty should not automatically be equated with gender inequality, and wealth does not necessarily mean gender equality. The report shows that the gender gap can be caused by many different factors, and that efforts must be focused on different areas in different countries. Therefore the Norwegian model cannot be transferred automatically to our partner countries. Our approach must be tailored to the situation on the ground.

2.2 Life cycle and diversity

It is an oversimplification to regard girls and women as a single, homogeneous group. There are great variations, and different groups have different needs and interests. Norwegian policy must address this diversity. Special measures are also needed to combat discrimination against sexual minorities.

Textbox 2.3 Children’s clubs in Nepal

«Before I became a member of the Children’s Club, I thought my life was over. I was treated badly by my boss and was too shy to tell him what I thought. Then I joined the Children’s Club and learned that children and children working as domestic servants also have rights. I learned to express myself and speak in front of other people. I learned to believe in myself. I became bolder towards my boss. Now he lets me go out and have friends and free time. I feel like a person, I am demanding my rights.» (Girl, age 16)

Norway has been supporting a network of children’s clubs in Nepal through UNICEF. The majority of the members are child workers, and many are domestic servants.

Our policy for promoting women’s rights and gender equality must have a life-cycle perspective. This is important both in order to get an accurate picture of the situation and in order to target our policy. Poverty and marginalisation affect children and young people particularly severely, and girls more so than boys. Girls are often far less visible and active in society than boys. There may be severe restrictions on how and where girls can participate. More boys have access to education than girls, and boys stay in the school system longer than girls. Discrimination against girls starts at birth – and in some cases even earlier. Modern-day technology makes it possible to choose not to give birth to girls. The problem is very real. In some parts of the world many more female than male foetuses are aborted. According to figures presented by the international development agency Plan, this results in a shortage of girls in the order of 100 million. Discrimination against girls also leads to considerable disparities in the health status of girls and boys. Particular health problems are associated with teenage girls who are married off and give birth before their bodies are fully mature. Early marriage and pregnancy often put a stop to a girl’s education. For many girls, pregnancy means automatic expulsion from school. The early sexual debut of many girls, often with older men, is a clear factor in the spread of HIV and AIDS. Girls are also physiologically more at risk of infection than boys, and sexual violence and coercion further increase their vulnerability. In sub-Saharan Africa, girls account for three quarters of all HIV-infected people in the age group 15 to 24. Ensuring that girl’s needs are sufficiently safeguarded in efforts to promote gender equality and when working with children and young people is a particular challenge. General programmes are often designed for adults, and are not necessary suited for children. Programmes for children must be tailored to reach both girls and boys.

Our policy must also be designed to address the situation of older women and widows, particularly with regard to inheritance, land, housing and property rights. In many countries women do not have such rights. The situation of single and divorced women also deserves special attention in many countries.

Textbox 2.4 Strategic efforts for indigenous peoples in Guatemala

One of the aims of Norway’s efforts in Guatemala is to enhance the indigenous peoples’ opportunity to gain political influence. Indigenous women are the most important target group. Despite the fact that indigenous peoples make up the majority of the population, they are politically, economically and socially marginalised. Since 2005, Norway has granted university scholarships to Mayan women, and we are pleased with the results. Indigenous women have qualified for key positions in politics and public administration, for example in the Government’s Secretariat of Planning and Programming. Norway has also been supporting research on ways to increase indigenous people’s participation in political processes. This research will provide more knowledge on how democracy-building efforts can be designed to include both women and men from indigenous groups in a multicultural, multi-ethnic society where several languages are spoken.

Women are discriminated against in all countries – albeit to different degrees and in different ways. Many women face double discrimination, as poverty is in itself a cause of discrimination. Other factors that can influence or increase discrimination are membership of a minority ethnic community, indigenous affiliation, religion, sexual orientation, gender expression and identity, disability or serious illnesses such as AIDS.

Groups and individuals who face multiple discrimination, such as women with indigenous backgrounds, are particularly vulnerable. Indigenous groups are often politically, economically and socially marginalised. Thus indigenous women are in a particularly vulnerable situation, facing marginalisation not only due to their gender, but also due to their ethnicity and their poverty. This may be part of the reason why indigenous women are overrepresented among victims of human trafficking, and why sexual abuse against women from minority groups is so prevalent in conflict situations and war. It is less likely that an offender will be prosecuted for sexual abuse in cases where the victim is an indigenous woman than in cases where the victim is from the majority population. And it is even less likely if the offender is from the majority population.

2.3 Mobilisation of boys and men

It will only be possible to achieve gender equality if we involve not only girls and women, but also boys and men. There is no getting around the fact that men and male gender roles are among the obstacles to gender equality, but it is also important to highlight that men are an important part of the solution. Men can play a key role in promoting women’s rights and gender equality, and they too should therefore be mobilised.

Gender inequality also has a price for men and boys. It is important to realise that while men and women tend to have different interests and live different lives, there are also great differences within the sexes. Men, too, can be subject to discrimination, often from other men with more power. This may be economic, political or military power, or the power conferred by age and authority. Boys as well as girls are vulnerable to sexual abuse.

Unprotected sex is a high-risk behaviour that accelerates the spread of HIV and AIDS, and has fatal consequences for both men and women. In many societies and circles, it is acceptable for men to purchase sex. The combination of purchasing sex and failure to use condoms considerably increases the risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases by all those involved, including the men themselves and their regular partners.The lack of acceptance of homosexuality in many societies drives homosexual boys and men into the prostitution market, both as buyers and sellers of sexual services involving other boys and men. Moreover, many boys feel constrained by rigid gender role patterns and norms of masculinity, and those who are unable to live up to social expectations lose out.

Textbox 2.5 Awareness-raising among men in the Philippines

It is important to raise young men’s awareness of gender disparities in empowerment and freedom of choice, particularly with regard to sexual relations. Norwegian NGOs are supporting projects that encourage young men to promote gender equality and mutual respect between the sexes. In the Philippines, for example, the Women’s Front of Norway and FOKUS (Forum for Women and Development) are cooperating with the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW). Young men attend courses led by male instructors where they discuss gender roles and take part in group work with their peers. The course participants have been particularly affected by meeting former prostitutes. The insight they gained into these women’s backgrounds, marked by poverty and abuse, gave them greater respect for the women as individuals. They also gained an understanding of how their own behaviour, including the purchase of pornography and sexual services, contributed to the oppression and degradation experienced by these women. These young men, prospective agents of change, found that it was not easy to convince other men, particularly members of the older generation. But when they managed to do so, they saw it as a great personal victory.

It is essential that our policy takes a critical approach to male and female roles in relation to cultural and religious factors. There are great national and regional differences in this respect. In certain religiously conservative countries, it is not just a matter of redefining roles, but of men actually relinquishing their control over women. This raises issues of fundamental conceptions of honour and other deeply rooted traditions. It is one of the main challenges we are facing in our international development policy in this area.

Therefore, it is essential that our international development policy includes measures targeted specifically at boys and men. But we must find a way of focusing on men and boys without pitting men and women against each other. The measures we implement must promote an awareness among men of the need for change, a realisation that the situation in many societies where men have a virtual monopoly on power is not viable, and that power-sharing is the key to progress and a well-functioning society. We must ensure that our activities demonstrate that men too have a clear self-interest in gender equality and women’s full participation in development processes. Better utilisation of resources means more rapid development and a better life situation for everyone. Breaking down rigid gender role patterns leads to more freedom for both sexes. In societies without strong expectations or preconceived ideas about how people should behave, individuals have greater freedom of choice – and this also applies to men.

2.4 International normative framework

There is a comprehensive set of widely recognised norms that provide an international framework for efforts to promote women’s rights and gender equality as well as giving them their legitimacy. CEDAW is the central human rights convention relating to girls and women. It sets out the obligations of states to eliminate discrimination against women in such areas as family relations and entering into and dissolution of marriage, education, health and participation in political and economic life. Almost all of the countries that receive emergency relief and development assistance from Norway have acceded to the Convention. The States Parties are to report every fourth year to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, which is responsible for monitoring the progress made in the implementation of the Convention. On the basis of the reports and subsequent dialogues with the countries concerned, the Committee draws up recommendations for each country.

These recommendations provide a good basis for efforts to promote women’s rights and gender equality in the various countries. However, Sudan and Somalia are among the countries that have not acceded to CEDAW. Other countries have made reservations with regard to some of the obligations, such as the prohibition of discrimination against women in national legislation.

Norway’s policy is to encourage countries that have not yet done so to accede to the convention without any reservations. Norway has ratified CEDAW and will seek to comply with its provisions, including in its international development policy.

The UN has also established several Special Rapporteur positions, for example a Special Rapporteur on violence against women. The Special Rapporteurs conduct country visits, collect data and publish annual reports containing recommendations to the Human Rights Council. Women’s rights are on the agenda of the General Assembly and the annual sessions of the Commission on the Status of Women. Regional organisations such as the African Union have also adopted declarations on women’s rights and gender equality, which the member states have undertaken to follow up and report on.

In 2000, the UN Security Council adopted resolution 1325 on women, peace and security, according to which women are to participate on equal terms in decision-making processes related to conflict resolution, peace and security. Girls and women are to be protected against the increased brutality and sexual violence and abuse that occurs in many situations of armed conflict. The resolution is not legally binding, but it provides important political guidelines.

Action plans adopted at UN summits are not legally binding either, but they are politically binding. The Platform for Action adopted at the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995 set out a broad agenda for promoting women’s rights and gender equality globally. The international community managed to agree on an ambitious final document aimed at promoting women’s empowerment and access to resources in all areas of society. Important themes and perspectives included the feminisation of poverty, health, income and inheritance, land, housing and property rights. The Conference also addressed the alarming prevalence of violence against women and highlighted the importance of ensuring that women participate in, and have an opportunity to exert an influence on, working life and political processes. The Beijing Conference also marked a breakthrough in efforts to devise a broader strategy for promoting women’s rights and gender equality in all sectors of society. It was agreed that gender issues should not to be confined to a separate sector where they only have a limited effect on other policy areas. The Platform for Action is based on the principle that all projects and programmes must be analysed in terms of their effects on women and men, respectively, before any decisions are taken. At the same time, the need for targeted measures to eliminate existing disparities and power imbalances between the sexes is emphasised. In 2005 the UN Commission on the Status of Women, which brings together all UN member states, assessed the progress made in the implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action. It concluded that there is still a big gap between global aims and activities and results at national level. As the progress made has been modest, the Beijing Platform for Action remains highly relevant.

Textbox 2.6 Universal human rights conventions and guidelines

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (UN) (1966)

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (UN) (1966)

UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979) and the Optional Protocol (1999)

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989)

UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (1993)

UN Security Council resolution 1325 on women, peace and security (2000)

UN Millennium Declaration and the Millennium Development Goals (2000)

Many other UN summits have dealt with women’s rights, which has led to increased focus on the issue. At the 1993 UN World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna, the rights of women and girls were put on the agenda in earnest. According to the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, gender-based violence and all forms of sexual harassment and exploitation are incompatible with the inherent dignity and worth of the human person. The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo was a milestone in the recognition of the principle of the rights of families and individuals to control their own fertility and to enjoy good sexual and reproductive health. The Conference also recognised the rights of young people in this area, which was an equally important step forward. Norway played a proactive role both in Cairo and in Beijing in efforts to liberalise restrictive abortion laws, but the progress made in this area was limited. The vital role played by women in environmental management and development was underscored at the summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 and in Johannesburg 10 years later. In Agenda 21, the action plan adopted at Rio, it was established more clearly than before that women are to be empowered through full participation in decision-making.

The key recommendations of the various UN summits in the 1990s were incorporated into the UN Millennium Declaration, which was adopted by world heads of state and government in 2000. The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are included in this declaration. Although the goals themselves were not new, they reflect a renewed global commitment in the sense that concrete deadlines were set, indicators agreed, and annual reporting routines established. All the MDGs are important in terms of gender equality, but two of them are specifically targeted at improving the situation of women. These are MDG 3 concerning gender equality and women’s empowerment and MDG 5 concerning maternal health.

Textbox 2.7 Key world conferences and UN summits

World Summit for Children (New York, 1990)

UN Conference on Environment and Development (Rio de Janeiro, 1992)

UN World Conference on Human Rights (Vienna, 1993)

International Conference on Population and Development (Cairo, 1994)

UN Fourth World Conference on Women (Beijing, 1995)

UN Millennium Assembly (New York, 2000)

International Conference on Financing for Development (Monterrey, 2002)

World Summit on Sustainable Development (Johannesburg, 2002)

UN World Summit (New York, 2005)

The review of the Millennium Declaration at the UN World Summit in 2005 reaffirmed that women’s empowerment must be mainstreamed in all efforts if the MDGs are to be achieved. The Summit led to the adoption of four new targets at the General Assembly the following year. Three of these targets are important for advancing women’s empowerment: incorporation of goals concerning full employment and decent work into national and international development strategies; universal access to treatment for HIV and AIDS by 2010; and universal access to reproductive health by 2015. Several countries voiced scepticism about the resolution when it was put to a vote in the General Assembly. The UN has not yet begun to refer to the new targets in its annual reporting on the MDGs.

It is clear that the challenges related to women’s rights and gender equality are not due to a lack of international rules and guidelines. There is a comprehensive normative framework that enjoys broad support, at any rate on paper. However, a great deal remains to be done in translating these commitments into action. One of the main tasks in this respect is to persuade countries to incorporate their international obligations into national legislation and implement them in practice.

2.5 Previous experience

Women’s rights and gender equality have been important themes in Norway’s development cooperation for several decades, but the approach has varied. In some periods, the focus has been on individual programmes, while in others the main strategy has been to integrate the gender perspective into all of our development assistance efforts. In international development circles, the term «mainstreaming» is generally used to describe the latter type of thematic integration.

In 2005, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Norad commissioned the Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research to carry out an evaluation of the Strategy for Women and Gender Equality in Development Cooperation (1997–2005). The evaluation revealed significant weaknesses in the institutionalisation and implementation of efforts. Despite the fact that this was a high-priority area politically, with strategies setting out clearly defined aims, the gender perspective receded into the background when development plans and projects were implemented. The reporting routines did not reveal the failure to translate political priorities into practical assistance. The funds earmarked for this purpose were reduced, as were expertise and capacity. In 2002, the special allocation for gender-related measures and activities was discontinued in connection with a large-scale budget reform, and was replaced by an explicit policy recommendation prescribing that gender equality was to be promoted under all the development budget lines. The number of employees in the Foreign Service with thematic responsibility for this issue was also reduced. Gender equality courses were no longer provided as part of in-house training for Norad and Foreign Service employees. The idea was that theme-specific expertise and training were to be mainstreamed.

In retrospect it is clear that the intention to mainstream the gender perspective came to nothing. In practice it was mere rhetoric. Similar evaluations carried out by other actors have reached the same conclusion. Thus, this criticism does not just apply to Norwegian development assistance, but seems to be more generally applicable.

2.6 Current policy and practice

The negative evaluation in 2006 of Norwegian efforts to mainstream gender equality in development cooperation led to a turnaround in Norway’s policy. Since then, new plans and tools have been developed to address priority areas that are vital for the empowerment of girls and women.

Increased capacity and expertise are needed to achieve these priorities, and resources from many areas are being drawn on. It is generally recognised that this is a complex area involving major challenges. The process of change will take time. In order to get this work off to a good start, a three-year project (2006–2009) on women’s rights and gender equality has been established in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The project, which is headed by the Ministry’s ambassador for women’s rights and gender equality, aims to boost efforts in this field and make them more visible. It will work closely with all relevant units in the Ministry and Norad. The embassies play a central role. They have the day-to-day responsibility for dialogue with the host countries’ authorities, and they administer Norwegian funds and are important sources of information in the field. There will be regular contact with civil society representatives and multilateral and international actors. The ambassador is supported by a team organised under the Section for Global Initiatives and Gender Equality in the Foreign Ministry.

Other ministries will also play an important role in promoting women’s rights and gender equality, for example in administering Norwegian cooperation with relevant UN organisations and the relevant authorities in developing countries.

It is generally agreed that a broad range of tools is required in order to succeed. All the central development cooperation channels and processes must be utilised. We will build on the best of our previous experience, both in implementing a broad range of measures to mainstream the gender perspective in all policy goals, and in specifically targeting activities to empower women. Women’s rights and gender equality must be explicitly and comprehensively incorporated into Norway’s development cooperation efforts. To do so, we must increase expertise in this field both in Norway and among our cooperation partners. Key tools in the Government’s efforts will be targeted measures, competence- and capacity building and earmarked resources. Strong political focus, management accountability, training programmes and specific follow-up requirements are essential.

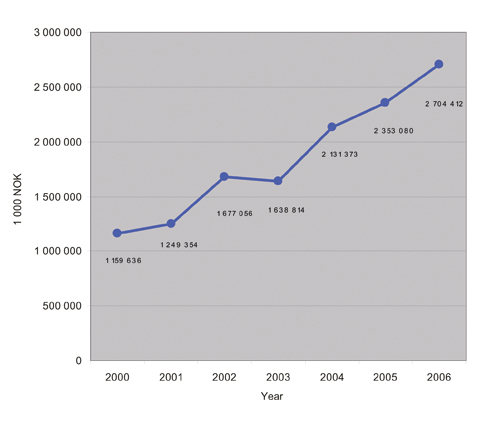

Figure 2.1 OECD’s figures for aid in support of gender equality and women’s empowerment, for all OECD donors (average) and for Norway.

2.6.1 Economic and administrative consequences

Gender equality is to be promoted both by mainstreaming the gender perspective in all policies and through specific targeted activities. This two-pronged approach is to be reflected in Norway’s development assistance budget by earmarking allocations and including gender-related objectives and criteria for disbursements under all important budget lines. Administrative routines must ensure that these objectives are achieved.

Efforts to promote women’s rights and gender equality are to be stepped up. This will mean giving priority to gender-related measures and activities within existing budgetary frameworks. However this should not have a negative impact on other important priority areas such as peacebuilding, humanitarian assistance and human rights, good governance, the fight against corruption, oil and energy, and the environment and climate change. On the contrary, effectiveness in these areas will be increased through stronger focus on women as a resource in combating poverty and promoting development. The budget will be an important tool for achieving results. A separate chapter in the Foreign Ministry’s budget proposal monitors gender-focused expenditure. The aim is to see a steady increase in the percentage of development funding earmarked for this purpose. This is in keeping with the Action Plan for Women’s Rights and Gender Equality in Development Cooperation 2007–2009.

2.6.2 Action plans

A series of action plans have been drawn up that set out criteria and guidelines for promoting women’s rights and gender equality in development cooperation.

The Action Plan for Women’s Rights and Gender Equality in Development Cooperation was launched on 8 March 2007 and covers the period 2007–2009. The purpose of the plan is to boost Norway’s efforts in this field in the international community and among our cooperation partners. It is the result of a comprehensive process involving broad-based dialogues with partners in Norway and abroad. The action plan sets targets and stakes out the course for the realisation of women’s rights and gender equality both as a separate priority area and as an integral dimension of the Government’s other development cooperation priority areas. The action plan is the most important operational tool we have today for ensuring that women’s rights and gender equality are given the status and priority needed to achieve our aims.

The Norwegian Government’s Action Plan for the Implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) on Women, Peace and Security was launched on 8 March 2006. It provides guidelines for safeguarding the rights of girls and women in war and conflict situations, increasing the participation of both women and men, and mainstreaming the gender perspective in Norway’s conflict-prevention and peacebuilding efforts. The plan provides guidelines for Norway’s high-profile engagement in a number of conflict areas worldwide.

The Government’s Plan of Action to Combat Human Trafficking (2006–2009) sets out measures to intensify efforts to empower women and reduce their vulnerability to recruitment to and abuse in the slave trade of our times. Most of the victims are women and children, both girls and boys, who are trafficked across borders for sexual exploitation through prostitution, for forced labour or for the illegal organ trade.

The Government’s International Plan of Action for Combating Female Genital Mutilation was adopted in 2003, and has been extended to the end of 2009. The plan calls for intensified efforts to combat female genital mutilation and for the integration of these efforts into ongoing cooperation in the health and education sectors. The issue will be included in Norway’s political dialogues at country level where relevant.

Other strategies and action plans for development cooperation that are important in this context include the Action Plan against Forced Marriage(2008–2011), Aid for Trade: Norway’s Action Plan(2007), the Position Paper in Development Cooperation on Norway’s HIV and AIDS Policy(2006) and the Action Plan for Environment in Development Cooperation(2006).

2.6.3 Cooperation with partner countries

Policy dialogue with the authorities of our partner countries is the cornerstone of Norway’s development cooperation. We will push the gender perspective higher up on the development agenda through targeted use of the relevant forums and channels for policy dialogues and the use of development assistance. We will utilise our opportunities to exert an influence, including in situations where women’s rights and gender equality are not an explicit priority for our partners. At the same time, however, we must ensure that our policy is in keeping with the principle of country ownership. The promotion of gender equality must be linked up to the partner countries’ own development targets and international commitments – for example regarding CEDAW if the country has acceded to it – and tailored to local challenges and opportunities for change.

In many of our partner countries, the authorities responsible for gender equality are marginalised in relation to national planning and budget processes. These authorities and other gender equality stakeholders are important actors and cooperation partners for Norway.

Textbox 2.8 Maternal health services in Malawi

Malawi is the country where Norway is doing most to promote women’s rights and gender equality. The maternal mortality rate in Malawi is among the highest in the world. The country’s authorities recognise the seriousness of the situation and are giving higher priority to improving maternal health services. However, there is still a great need for supplementary measures.

Norway is financing a cooperative initiative between three Norwegian university hospitals (Ullevål, Haukeland and Tromsø) and the maternity ward of Bwaila Hospital, which is the main hospital in the capital, Lilongwe. Bwaila Hospital is the leading institution for the training of midwives in Malawi, and the initiative is expected to have a positive impact throughout the country. The cooperation between the two countries is mainly focused on improving systems and routines, and providing on-the-job training by health personnel from Norway. Some equipment will also be provided.

At country level, we must constantly assess which gender equality challenges are most important and which local actors we can draw on at any given time. The situation varies greatly from country to country. In many countries, there are discrepancies between policy and practice. This may provide an opening for an effective policy dialogue. It is important to identify and utilise the opportunities that arise in forums and arenas where Norwegian actors are already active, have gained credibility and have developed good relations. Relevant issues to address include empowerment and participation, access to and control over resources, and the impact of projects and programmes – for both women and men. Women’s rights and gender equality must be prioritised in day-to-day activities, through dialogue with and support for the country’s own agents of change in the government, in publicly elected bodies and in civil society.

The Government does not wish to sidestep sensitive issues, such as abortion and homosexuality, which are prohibited by law in many countries. We must find an approach that is challenging, without being unnecessarily offensive. It is important to bear in mind that this is a long process, and that we must «hasten slowly». Norway can provide moral and financial support to organisations and projects that promote rights in these areas. At the same time, we should use our policy dialogue with national authorities to pursue these issues.

2.6.4 Cooperation with civil society

Civil society has played an important role in shaping democratic development in Norway. Women’s rights and gender equality are one of the areas where this can be most clearly seen. Women’s participation in NGOs and the establishment of women’s networks and organisations have been instrumental in putting women’s issues on the national agenda. Many Norwegian NGOs and research institutions have acquired broad experience and extensive knowledge of women’s rights and gender equality. A number of Norwegian NGOs that work specifically with gender issues are organised under the umbrella organisation FOKUS – the Forum for Women and Development. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has high expectations of Norwegian NGOs’ efforts to promote women’s rights and gender equality in development cooperation. However, as is the case with other actors, the picture is complex and the results uneven. The challenge lies in acquiring the right expertise not only in the field of gender equality but also in the field of international development. Working methods and approaches that have worked well in Norway cannot be transferred automatically to developing countries.

Textbox 2.9 Norway supports the right to safe abortion on demand

Norway is seeking to promote women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights. One of our main partners in these efforts is the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), one of the world’s largest NGOs, with member associations in 150 countries. As the IPPF is a non-governmental network, member associations can take a proactive role in issues that are sensitive in the country concerned, and provide reproductive health services to groups that otherwise would have no access to such services. In 2006, Norway contributed to a new multi-donor fund under the IPPF to promote safe abortion, which supported 45 different measures in 32 developing countries during its first year of operation.

The lack of access to contraception and safe abortion on demand causes women and their families great suffering. Progress in these areas is essential in order to achieve the MDG target on reducing maternal mortality. Unsafe abortions are primarily a poverty-related problem in countries that have restrictive abortion legislation. This problem can only be eliminated by providing safe and legal abortion services. Organisations that promote safe abortion on demand are fighting an uphill battle, particularly due to the restrictive policy of the US. Norway’s efforts in this field are therefore important. Norway provides about NOK 50 million a year to the IPPF, NOK 10 million of which goes to the safe abortion fund. This is Norway’s largest individual contribution to the promotion of women’s rights that is channelled through an NGO.

There is broad popular support in Norway for gender equality. Civil society has played a decisive role in promoting women’s rights and putting them on the political agenda. Various organisations have provided key arenas for articulating women’s demands and setting women’s own priorities. The efforts made by women themselves to organise and mobilise have been crucial. It is therefore natural for Norway to give priority to supporting civil society in the South. Civil society plays an important role as an advocate for women’s rights and in holding the national authorities accountable for their obligations in this field. This is why national and regional women’s organisations and networks in developing countries are given such high priority as cooperation partners.

Norway will pursue a clear policy in its efforts to promote gender equality and women’s rights. In some cases, local civil society representatives are the most important actors. For example, Norway’s efforts with regard to culturally rooted discrimination against women including in sensitive areas – are frequently channelled through local agents for change. This applies, for example, to abortion, female genital mutilation, homosexuality and the general promotion of women’s rights in the interface between state law and customary law and practices. Although women’s formal rights are in many cases safeguarded by national legislation, the national authorities may not be able to enforce this legislation at the local level. In such cases, local civil society actors play a key role.

2.6.5 Cooperation with multilateral actors

Norway has played a key role in efforts to ensure that the gender perspective is mainstreamed in the activities of multilateral development organisations. We have been among the leading advocates of establishing accountability for these efforts at a high level in the UN and the development banks. Together with like-minded countries, Norway has insisted that these organisations develop strategies for mainstreaming the gender perspective systematically in all their activities.

Many of the first positions for gender advisers in UN organisations and the development banks were financed by Norway. Norway also played an instrumental role in the establishment of the position of Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on Gender Issues and the Advancement of Women. We have contributed ideas, personnel and funds for the development of strategies for promoting women’s rights and gender equality in development cooperation. In response to pressure from Norway, increasing priority is being given to these efforts. The organisations themselves are now financing these positions. In the board meetings of such organisations, Norway has actively espoused the view that gender equality is too important to be left to voluntary contributions from a handful of donor countries.

Textbox 2.10 Priority to girls’ education

In 1996, Norway took the initiative for a programme for the advancement of girls’ education in cooperation with UNICEF. The programme originally focused on certain countries in Africa and, because of the interest shown, was later extended to include additional countries. The final evaluation, which was carried out in 2003, showed that the Norwegian initiative had produced good results. More girls were completing their basic education. The programme has also helped to move girls’ education higher up on the agenda, both within UNICEF and in the various countries. However, the evaluation also revealed that UNICEF was not working in a sufficiently systematic way. This made it difficult for the organisation to make use of lessons learned and to scale up measures that were working well. With the support of Norway and other countries, girls’ education has now been mainstreamed as one of UNICEF’s five main priorities. Norway is a major donor to the organisation.

Since 2003, Norway has provided approximately NOK 450 million annually for girls’ education. This is the largest single Norwegian contribution that can be defined as being targeted towards women. At the same time we have managed to make UNICEF accountable for addressing this issue. New donors have been mobilised. The United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative, which is specially designed to advance girls’ education, has been established. Thirteen organisations, including the World Bank, participate in the initiative.

These efforts are important because the multilateral organisations have considerable influence. More can be gained by mainstreaming the gender perspective in the activities of these institutions than can be achieved by the various donors on their own. The World Bank and UNDP, for example, play key roles in policy dialogue with partner countries and advise them on their national development strategies. The World Bank and the regional development banks transfer substantial resources, and the other UN organisations provide expertise and networks that are far more extensive than the resources available to individual countries. The World Health Organisation (WHO) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) are playing a key role in promoting women’s health and access to family planning. The United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM), which is the only organisation in the UN system dedicated exclusively to fostering women’s empowerment and gender equality at the global, regional and national levels, is another key cooperation partner. UNIFEM’s mandate is to play an innovative and catalytic role in efforts to promote the rights of women and gender equality at country level and vis-à-vis the rest of the UN system.

A number of evaluations show that there was less focus on women and gender equality in many multilateral organisations towards the end of the 1990s. In fact, mainstreaming the gender perspective in all activities, whereby everyone became responsible for everything, meant that no one had real responsibility for this area any more. This was the case for Norway’s efforts as well. Norway’s renewed focus on women’s empowerment and gender equality therefore also applies to its efforts in the UN, the World Bank and the regional development banks. In the board meetings of these organisations we are calling for stronger leadership, clearer objectives and better reporting of results. This applies both to the measures exclusively targeted at women and to the mainstreaming of the gender perspective in broader programmes.

Norway is again providing earmarked funds for promoting the gender perspective in key multilateral organisations. Experience has shown that when donors identify specific priorities, these issues move higher up on the organisation’s agenda. Gender advisers in the UN and the development banks have more influence if their policy guidelines and instruments are backed up by funding. Norway has, for example, played a proactive role in the development of a new World Bank action plan for mainstreaming gender equality in development. The plan, which is entitled Gender Equality as Smart Economics, focuses on the Bank’s role in securing women’s access to financial, land, product and labour markets. The action plan was adopted by the Board of Directors of the World Bank in 2006, and Norway is providing funding for its implementation.

Increased focus on women’s empowerment and gender equality is one of the main causes advocated by Norway in the efforts to strengthen the UN. Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg co-chaired the UN High-level Panel on System-wide Coherence. Norway actively supports the Panel’s recommendation to consolidate several important but small gender equality bodies into a new, more effective entity. A strong, independent UN entity dedicated to promoting women’s empowerment and gender equality in development processes is needed in order to ensure that the UN is able to fulfil its watchdog, advocacy and operational roles.

2.6.6 Cooperation forms

Strategies for mainstreaming the gender perspective in development policy cannot be developed in a vacuum, but must take into account general approaches to and discussions on development cooperation.

Since the second half of the 1990s, there has been a growing awareness that separate donor-initiated measures do not produce the development results expected. Donors therefore sought to ensure better utilisation of assistance funds by enhancing aid effectiveness. A new approach developed with a focus on coherent strategies, sector programmes and budget support. Although there was a big gap between theory and practice and considerable variation among donors, the importance of coordinating donor efforts with the aims and plans of governments and other recipients was increasingly emphasised.

The International Conference on Financing for Development in Monterrey in 2002 and the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness of 2005 were milestones in this regard. The Monterrey Consensus bears witness to the global consensus between donor and recipient countries that developing countries are responsible for their own development, and that more assistance should be provided to countries that have good governance and realistic plans.

According to the Paris Declaration, development processes should be clearly owned by the recipient. Donors should align themselves with recipients’ priorities and plans and insofar as possible utilise their systems and procedures. Donors should coordinate their activities among themselves. Today there is a much sharper focus on results and accountability, both within the country in question and between recipients and donors. However, implementation of the Declaration has led to a great deal of energy and resources being put into studies, meetings and dialogues with partner countries on sector-specific issues, while cross-cutting themes such as gender have been relegated to the background. This does not necessarily have to be the case. The aid effectiveness agenda provides new opportunities for mainstreaming the gender perspective. Dialogues on national development strategies and forms of cooperation such as budget support provide opportunities to bring gender equality efforts into policy making, particularly in ministries of finance and planning, but also in other ministries. However, a number of challenges remain, both in relation to the development of plans that integrate the gender perspective and in relation to the development of reporting routines.

Figure 2.2 Norwegian bilateral assistance1 with women’s empowerment and gender equality as the principal or a significant objective, 2000–2006

1Includes bilateral assistance provided through multilateral organisations

The principles of ownership and accountability must be interpreted broadly and inclusively. Responsibility for development processes must lie not only with finance ministries, but also with other line ministries as well as with gender equality authorities. Norway must be an advocate for the important role played by parliaments and civil society in the shaping of policy and the importance of ensuring that the executive authorities are accountable to the parliament and the whole population – both women and men. This means that partner countries are expected to integrate the gender perspective into their national development strategies and plans and into their national budgets. The results of development cooperation in terms of poverty reduction and economic and social development must benefit both women and men, both girls and boys. Explicit objectives related to women’s rights and gender equality, gender-sensitive indicators and gender-disaggregated statistics need to be developed. In connection with coordinating assistance with national strategies and plans, specific action plans and measures for promoting women’s rights and gender equality must be required. Norway must require that partner countries use public resources to the benefit of both women and men, not least in connection with new forms of cooperation, such as budget support.

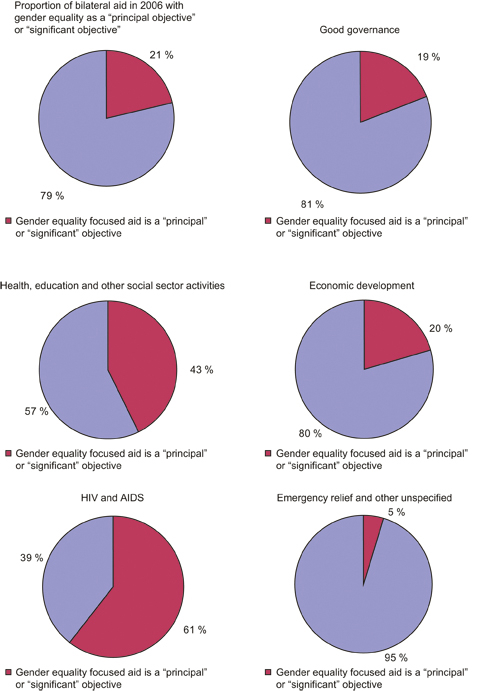

Figure 2.3 Proportion of Norwegian assistance targeted at women’s empowerment and gender equality

1Includes bilateral assistance provided through multilateral organisations