7 Clean wealth creation

The Government will seek to ensure that all wealth creation in Norway takes place in ways that do not pollute the environment or the industrial base with hazardous substances, including ecological toxins. The Government’s policy is that businesses should take responsibility for ensuring that production processes and products do not constitute a risk to health and the environment. In future, economic activity in Norway should take place without releases of ecological toxins, and such releases are to be eliminated as far as possible by 2020. The industrial sector will be required to meet strict standards, and industries themselves will be expected to take whatever steps are necessary to achieve the goal of eliminating emissions. The Government will seek to work more closely with relevant branches of industry and the social partners in its efforts to achieve its objectives. The Government also intends to apply stricter requirements to other economic activities such as farming, forestry, aquaculture and transport in order to reduce and eliminate releases of ecological toxins.

Figure 7.1 A clean environment enhances wealth creation

Photo: Marianne Otterdahl-Jensen

7.1 Wealth creation based on a clean environment

A large proportion of wealth creation in Norway is heavily dependent on a clean environment. An unpolluted environment is essential to fishing, fish farming, agriculture, the food processing industry, tourism and all outdoor activities. In the long term, therefore, there is no conflict between environmental considerations and wealth creation. On the contrary, a clean environment enhances wealth creation, and economic activities are more likely to gain public support if they do not pollute the environment. Moreover, strict environmental standards have sparked growth in some sectors, for example the production of technology for controlling emissions. The authorities will need to use policy instruments to encourage environmental efforts and bring about a shift towards environmentally sound products and technology. The market, too, is driving the development of «greener» technology through the growing demand for environmentally friendly goods and services. In the long term, the sustainability of businesses will depend on public confidence that products do not contain chemicals that present unacceptable risks to health or the environment.

7.2 Reducing releases from land-based industry

The Government will:

set strict environmental standards that will help to reduce releases of ecological toxins from industrial processes and promote the development of cleaner technology

ensure that there are no releases of priority ecological toxins from production processes after 2008 unless warranted by special circumstances

call on the industrial sector to formulate plans by 2010 showing how releases of ecological toxins are to be eliminated as far as possible by 2020

lay down specific requirements for industries that have particular problems related to releases of hazardous substances (such as the shipbuilding industry) while collaborating on training programmes with organisations in the relevant industries.

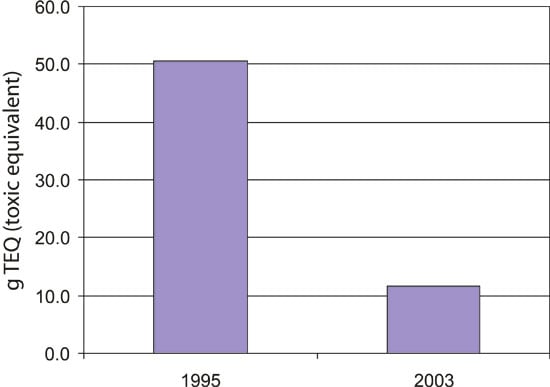

Figure 7.2 Reduction in dioxin emissions from manufacturing industries 1995–2003

Source Federation of Norwegian Industries

Table 7.1 Norway’s industrial emissions of ecological toxins in 2004, in tonnes and as a percentage of total emissions

| Industrial emissions (tonnes) | Industrial emissions ( % of total) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1,2-Dichloroethane (EDC) | 5 | 100 |

| Dioxins (in g TEQ)** | 35 | 41 |

| Hexachlorobenzene (HCB)** | approx. 0.001*** | * |

| Cadmium (Cd)** | 1.4 | 44 |

| Chlorinated alkyl benzenes (CABs, expressed as EOCl) | 0.02 | 100 |

| Mercury (Hg)** | 1.1 | 32 |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)** | 166 | 46 |

| Trichlorobenzene (TCB)** | approx. 0.003*** | * |

* No data available, but the distribution of emissions by source is probably similar to that of dioxins.

** Relatively high level of uncertainty in the emissions data gives a relatively high level of uncertainty in the calculations of percentages.

*** Rough estimate, with very high level of uncertainty.

Source Norwegian Pollution Control Authority

Releases of hazardous substances from industrial enterprises have been reduced substantially in recent years (see figure 7.2). This has come about through a combination of the requirements laid down by the authorities in discharge permits, market demands and efforts by the industries themselves. Yet major challenges still remain. Table 7.1 shows that the industrial sector accounts for substantial releases of certain ecological toxins. Moreover, the list of substances identified as ecological toxins keeps growing. In recent years, there have been releases of ecological toxins without the authorities being aware of this because too little was known about the properties of the chemicals when requirements and permits were drawn up. In addition, there are releases from smaller, non-industrial sources such as hospitals.

Figure 7.3

Photo: Marianne Otterdahl-Jensen

Ecological toxins are carried far and wide by winds and sea currents. Direct discharges also cause considerable problems locally and require major clean-up efforts. The need to clean up fjords where industrial activities were previously located is a case in point.

There are still substantial emissions of ecological toxins, indicating that we must continue to apply a strict policy to polluting industries. Manufacturing of metals and chemicals and the pulp and paper industry still account for a substantial share of Norway’s domestic emissions of a number of the priority ecological toxins. In future, we must also focus more on the many smaller sources of pollution and fugitive emissions that, taken together, may be causing just as much harm to health and the environment. Gaps in our knowledge pose a particular problem in efforts to eliminate releases of ecological toxins, and gathering and disseminating information and extending inspection and enforcement to new target groups will therefore be key elements of these efforts. The level of knowledge about hazardous substances varies widely in small enterprises, and they often need a considerable amount of follow-up.

Textbox 7.1 Emissions of ecological toxins have a range of causes

Emissions of ecological toxins from industrial activities are generated from the materials and auxiliary substances used.. Ecological toxins may be unintentional by-products of industrial processes, or they may originate from the raw materials used in these processes. PAHs and dioxins are just two examples of ecological toxins that are unintentional by-products of industrial processes. Trace amounts of heavy metals that may occur naturally in trees are released in the course of industrial wood processing. Processes in the metals industry are a source of similar emissions.

Before a discharge permit is issued pursuant to the Pollution Control Act, the negative impact of the activity in question on health and pollution must be assessed and the benefits of the activity weighed up against the drawbacks. For some substances, emissions may be so small that requiring further measures to reduce them would involve disproportionate costs.

Policy instruments and measures to reduce emissions

To deal with the remaining environmental problems posed by industrial emissions, the Government will continue to apply strict controls to industry. More stringent requirements will be introduced in keeping with advances in knowledge and the available technology. At the same time, the Government will encourage the application of new, sustainable technologies. The Government is working systematically to eliminate industrial releases of priority ecological toxins as far as possible in financial and technological terms. This effort is taking place at both national and international levels.

From now on, the Government has determined that enterprises will only be permitted to release priority ecological toxins if this follows specifically from emission limits set out in their discharge permits. This means that enterprises must have a good overview of their emissions of ecological toxins and obtain estimates of such emissions, including emissions originating from naturally-occurring ecological toxins in the raw materials they use. New discharge permits will make it clear that enterprises are responsible for investigating and evaluating their own handling of chemicals. After 2008, emissions of priority ecological toxins will only be permitted if warranted by special circumstances. Emissions limits will also be imposed in order to ensure that air and water quality are good in surrounding areas and to keep soil and sediments unpolluted. If releases of ecological toxins are due to the use of auxiliary substances, the authorities will encourage enterprises to find replacement substances so that these releases can be eliminated.

If ecological toxins are only present in very low concentrations, it is often not technically or financially feasible to remove them completely. It may thus be difficult to eliminate releases of these substances completely unless they come from auxiliary substances that can be replaced with other, less hazardous, chemicals. Consideration of what is technically and financially feasible will be part of the assessment when deciding whether special circumstances warrant permitting limited releases of priority ecological toxins from an industrial enterprise.

The Government expects the industrial sector to take responsibility for active efforts to continually reduce releases of priority ecological toxins. Further reductions will require both technological advances and further optimalisation of existing processes. To make it possible to evaluate whether enough progress is being made to ensure that releases are eliminated or minimised by 2020, the Government will require the industrial sector to draw up plans by 2010 outlining how reductions in emissions are to be achieved. This will raise awareness of the challenges that need to be dealt with before 2020. It will also give industry the incentive and the responsibility for adapting constructively to new requirements, for example by making use of existing environmental technology and developing new technology.

When enterprises that may generate large emissions of hazardous substances apply for discharge permits, emission limits will be determined on the basis of case-by-case assessments. As a general rule, strict limits will be set for emissions of ecological toxins, regardless of the recipient of the release. Most enterprises in this category are subject to the EU Directive concerning integrated pollution prevention and control (the IPPC Directive). This directive seeks to raise environmental standards in Europe by requiring that conditions in permits are based on use of the best available techniques (BAT) (see box 7.2). The directive has been implemented in Norwegian legislation and establishes requirements for listed industrial activities that may generate large emissions of hazardous substances. This directive is particularly important for the development of suitable standards for industries that release priority ecological toxins. The Norwegian authorities will take active part in international efforts to reduce and eliminate releases of environmentally hazardous substances, and will work to see that the requirement that permits are based on BAT is seen as a dynamic concept and that requirements are continually updated. The directive is currently being reviewed to assess the need for revision. Norway will follow this work closely and will provide input to the process. Among other things, the possibility of expanding the scope of the directive to include other industries such as aquaculture will be considered. This is a step the Norwegian Government would welcome, while emphasising that the IPPC Directive is only a minimum; the Norwegian authorities will impose stricter standards than those considered to be BAT wherever warranted by national or local considerations.

The new EU chemicals legislation REACH (Registration, Evaluation and Authorisation of Chemicals) will not directly affect the emission limits imposed on the industrial sector, but will nevertheless have a major impact on industrial emissions. REACH requires risk assessment by industry and evaluation by the authorities, and these requirements will also apply to emissions from production processes. In addition, the registration of chemical substances by manufacturers and importers under the REACH regulation will provide more information for the industries that use these substances.

Textbox 7.2 Best available techniques (BAT)

One of the fundamental principles of the IPPC Directive is that conditions in permits are to be based on the best available techniques (BAT). Guidelines have been issued in the form of BAT Reference Documents (BREFs) describing techniques considered to be BAT in a number of industries. At present, not all emissions originating from raw materials, such as the heavy metals (including mercury) released by the ferroalloy industry and secondary steel production, are addressed in BREFs. The conditions set by the Norwegian authorities in discharge permits require the use of BAT and techniques that minimise releases of hazardous substances. Norway is also seeking to have the emissions mentioned above included in BREFs.

The Government intends to add new provisions to the Pollution Regulations setting out requirements that will apply to specific industries and processes. These will apply to a large number of enterprises and will replace around 600 individual discharge permits. They will also introduce explicit environmental requirements for enterprises that are not currently subject to specific regulatory measures. Over time, provisions setting out environmental requirements for further industries will be added, thus establishing good, predictable framework conditions for small and medium-sized industrial enterprises. These provisions will also make the licensing system under the Pollution Control Act substantially simpler and more efficient for enterprises and authorities alike. Among other things, shipyards that carry out surface treatment of ships and offshore installations, which currently contribute substantially to the spread of ecological toxins, will be regulated by the new provisions. The provisions will be a tool for continuing reduction of emissions as additional industries are included, and the Government will assess on an ongoing basis the requirements that should apply to new industries. The Government will also collaborate with certain industries (such as shipyards) and with industry organisations in fields where there are challenges in reducing releases of hazardous chemicals.

Textbox 7.3 Regelhjelp.no

Regelhjelp.no is a website set up to help enterprises obtain information on the rules that apply to them and how to comply with them. It provides regulatory information on the following areas:

The working environment

Fire and explosives protection

Animal protection and welfare

Electrical systems and equipment

Consumer services

Pollution

Industrial protection

Food safety

Plant health

Product safety

It also presents coordinated information on internal control pursuant to health, safety and environmental legislation and the Act relating to food production and food safety, etc.

The Government will continue to give priority to communicating information on rules and regulations to businesses, as exemplified by the Regelhjelp.no website presented in box 7.3.

7.3 The oil and gas industry

The Government will:

conduct an overall review of status and progress towards the zero-discharge targets, and on this basis assess the need for further measures

introduce a unilateral ban on PFOS in fire fighting foams in the offshore sector

survey discharges, inputs and levels of environmentally hazardous substances and other pollutants in the Norwegian coastal current and on this basis assess the need for further controls on releases from various sources, including the offshore sector

promote the development of good models for integrated chemicals management in the offshore sector, taking account of the impact of the use of chemicals on health, safety and the environment.

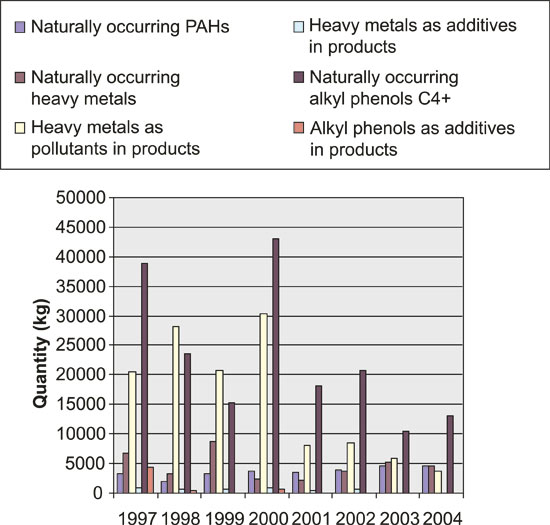

Oil and gas activities result in discharges of oil and chemicals to the environment both because chemicals are used in field development, drilling and production and because oil and other naturally occurring chemicals are discharged with produced water from the oil reservoirs. Discharges of hazardous substances by the oil and gas industry were relatively high in the 1990s, but have been reduced substantially since the zero-discharge targets were introduced (see figure 7.4). A major effort mounted to achieve these targets has yielded good results, though there is still a great deal of uncertainty regarding the long-term effects of discharges of produced water.

Textbox 7.4 General zero-discharge targets for the oil and gas industry on the Norwegian continental shelf

Environmentally hazardous substances

Zero discharges or minimal discharges of naturally-occurring environmentally hazardous substances that are also priority substances (as defined in national target 1 for ecological toxins) (see figure 3.4).

Zero discharges of chemical additives that are black-category (use and discharges prohibited as a general rule) or red-category substances (high priority given to their replacement with less hazardous substances). These categories are used by the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority, and further details are given in the Activities Regulations.

Other substances

Zero discharges or minimal discharges of the following if they might cause environmental damage:

oil (components that are not environmentally hazardous)

yellow category substances (not defined as belonging to the black or red categories and not on the OSPAR List of substances/preparations used and discharged offshore which are considered to pose little or no risk to the environment (PLONOR))

drill cuttings

other substances that may cause environmental damage

Figure 7.4 Discharges of environmentally hazardous substances by the petroleum industry 1997–2004.

Source Norwegian Pollution Control Authority

Textbox 7.5 What is produced water?

Produced water is water extracted from oil wells together with the oil. This water occurs naturally in the oil reservoirs and contains other substances occurring naturally in the reservoirs as well as chemicals introduced as part of the production process. Produced water contains quantities (varying from one oil field to another) of oil and environmentally hazardous substances such as PAHs and heavy metals.

The main reason why the authorities established zero-discharge targets for the offshore petroleum industry was that large and increasing quantities of oil and chemicals were being discharged to the sea and further increases were expected, chiefly due to the steady growth in the quantity of produced water from the oil fields. The zero-discharge targets are a precautionary measure formulated to ensure that discharges of oil and hazardous substances to the sea do not cause unacceptable damage to health or the environment.

The zero-discharge targets mean that as a general rule, no oil or environmentally hazardous substances, whether chemicals during the production process or occurring naturally (see box 7.4), may be discharged. They are based on the precautionary principle, and both new and existing installations were required to achieve them by the end of 2005. In other words, from 1 January 2006, all offshore operations are required to meet the zero-discharge targets. The requirements that apply to the Barents Sea–Lofoten area are even stricter than those that apply to the rest of the continental shelf. In this area, no discharges to the sea are permitted during normal operations (see box 7.6). In Recommendation S. No.225 (2005–2006) the Storting states that «the existing zero-discharge regime for the Barents Sea–Lofoten area must also apply as far as possible to onshore facilities.»

Textbox 7.6 Special requirements for oil and gas activities in the Barents Sea

The following applies to discharges during normal operations:

No discharges of drill cuttings or drilling mud. Drill cuttings from the tophole section may normally be discharged provided that they do not contain substances with unacceptable properties, and that they are only discharged in areas where assessments indicate that damage to vulnerable components of the environment is unlikely.

No discharges of produced water. A maximum of 5 % of the produced water may be discharged during operational deviations provided that it is treated before discharge.

No discharges to the sea in connection with well testing.

It is planned to conduct an extensive review of status and progress towards the zero-discharge targets, and on this basis assess the need for further measures in the next white paper on the Government’s environmental policy and the state of the environment in 2007.

A preliminary assessment of the progress that has been made shows a reduction of around 85 % in releases of chemical additives from production processes from 2000 to 2004. For technical and safety reasons, however, discharges of certain of these substances to the sea will continue after 2005. These will chiefly be certain hydraulic fluids, emulsion breakers and pipe dope. Efforts to find alternatives to these substances as well will continue, however (see box 7.7 and the requirements of the Product Control Act and the health, safety and environment regulations). No increase in the use of environmentally hazardous substances to boost production on older fields will be permitted if it involves the discharge of such chemicals. The reduction in releases is noted with satisfaction, and shows that the official targets, combined with the industry’s ability to use more environmentally sound technology, can almost eliminate discharges to the sea.

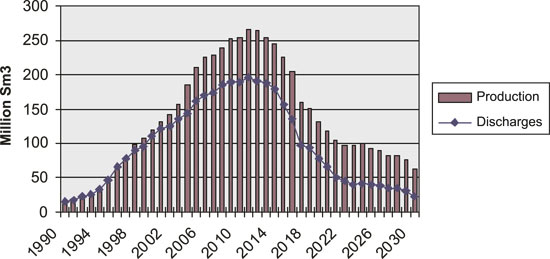

Figure 7.5 Historical and projected figures for production and discharges of produced water on the Norwegian continental shelf

Source Norwegian Petroleum Directorate

The target for naturally-occurring environmentally hazardous substances has not been met to the same degree. Produced water contains residues of oil and chemicals – both chemicals added as part of the production process and naturally-occurring chemicals. The oil and gas industry has taken significant steps in recent years to reduce discharges of produced water and meet the zero-discharge target, and has made investments of approximately NOK 5 billion to this end. As a result, the amount of oil per litre of water discharged to the sea has been reduced. However, the total quantity of produced water has risen during the same period, so that there has as yet been no net reduction in the total discharges of oil and naturally-occurring substances with produced water on the Norwegian continental shelf. The rise in discharges to the sea must be viewed in the context of the evolution of Norway’s offshore oil industry. Many of the oil fields are now mature, and in accordance with the principles of sound management of petroleum resources, one of the objectives is to maintain production and improve the recovery factor. On many oil fields, this leads to an increase in production of produced water. According to projections from the Petroleum Directorate, the quantity of produced water will rise until 2011 and then begin falling again in 2012 (see figure 7.5). High oil prices may extend the lifetime of these oil fields, and thus also the quantities of chemicals used and the volume of produced water discharged to the sea. Projections of oil and water production and discharges of environmentally hazardous substances from the oil and gas fields will be incorporated into the review of status and progress towards the zero-discharge targets.

The offshore sector and land-based petroleum industry have contributed substantially to discharges of perfluorooctyl sulphonate (PFOS). PFOS is an ecological toxin that has been used in fire fighting foams, and releases have occurred during testing of fire-fighting systems. There are other chemicals available for this purpose which are considered acceptable from a safety point of view. PFOS is in the process of being phased out in new systems, and the quantity of PFOS in offshore installations has been reduced by more than half through voluntary substitution. Large quantities still remain, however – the equivalent of approximately 2.5 tonnes, or around one-third of the all the PFOS found in Norway.

Textbox 7.7 Regulatory framework for health, safety and the environment in Norway’s offshore industry

There is a single regulatory framework for health, safety and the environment for Norway’s petroleum industry, which is administered jointly by the Petroleum Safety Authority Norway, the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority and the Norwegian Board of Health. The regulations address safety, the working environment, health, the external environment and financial matters.

Discharges of environmentally hazardous substances and other pollutants from inshore petroleum installations and onshore facilities, as well as from other land-based industry, can enter the Norwegian coastal current and add to its pollution load. Discharges in these areas affect more vulnerable parts of the ecosystem than discharges further out to sea, such as spawning grounds and nursery areas for fish larvae and fry. Discharges of environmentally hazardous substances and other pollutants that end up in the coastal current are also likely to be carried north and end up in even more vulnerable areas in the Arctic. To assess the environmental risk associated with this type of pollution, the Government will take steps to register discharges, inputs and levels of pollution in the Norwegian coastal current, and how much originates from the offshore industry.

A single regulatory framework for health, safety and the environment has been established for the offshore industry (see box 7.7), and requires an integrated approach to health, safety and environmental issues. Cooperation between the supervisory authorities is used to ensure that the overall result is the greatest possible reduction of risks to health and the environment, including the working environment. A white paper on health, safety and the environment in the petroleum industry (Report No. 12 (2005–2006) to the Storting) includes a broad discussion of the health risks associated with the use of chemicals, and outlines a range of measures to reduce these risks.

7.4 Reducing releases from the construction industry

The Government will:

ensure that the construction industry eliminates the use and releases of ecological toxins

work together with the construction industry to develop more environmentally sound alternatives.

The construction industry is a large industry with a high level of activity, and puts pressure on the environment through its use of substances and products containing hazardous substances and through the generation of substantial quantities of waste. The national targets, including those relating to priority ecological toxins (see Chapter 3), apply to releases from the construction industry.

The active involvement of the construction industry will be essential in meeting the targets relating to chemicals. The Government will invite the industry to make proposals for how it can make an active contribution toward meeting the national targets that apply to chemicals. The Government will also cooperate with the construction industry in disseminating information on the substitution process. This collaboration effort will further use life-cycle assessments as a basis for identifying suitable areas for the development and use of more environmentally sound alternatives through appropriate choices of materials, methods and technology.

7.5 Releases from hospitals

The Government will:

review all releases to the environment from hospitals

consider whether specific conditions relating to releases from hospital activities should be included in discharge permits pursuant to the Pollution Control Act.

Hospitals use large quantities of medicines and cleaning agents. There are many cases in which these substances have escaped to the environment through the sewerage system. In theory, the release of chemicals or pharmaceutical waste from hospitals is subject to the prohibition against pollution established in the Pollution Control Act, but no specific requirements have been set for hospitals so far, nor have limit values been established for discharges of pharmaceutical waste to the sewerage system. Medicines are known to contain environmentally hazardous substances, but little is known about the properties and environmental risks associated with these chemicals.

Textbox 7.8 Environmental management systems in hospitals

As part of the Green Government project, all central government agencies were required to have introduced a simple environmental management system as part of their overall management system by the end of 2005. Environmental management is a tool to help companies and organisations improve their environmental performance. Some health institutions, such as Innlandet Hospital Trust in Kongsvinger and St. Olav’s Hospital in Trondheim, have also achieved third-party certification, for example under ISO 14001. By achieving certification, these hospitals have demonstrated their systematic efforts to reduce their impact on the environment and to continually improve their environmental performance.

New provisions on waste water recently added to the Pollution Regulations give municipal authorities clearer authorisation to lay down conditions relating to discharges to the sewerage system so that high standards can be maintained for sewage sludge quality and operations at waste water treatment plants. The Government wishes the municipalities to make use of these powers to lay down requirements relating to discharges from enterprises so that sewage sludge produced at their waste water treatment plants is of good quality. The Government will consider stricter regulation of discharges of pharmaceutical residues waste to sewerage systems (see Chapter 10.5).

The Government will direct the environmental authorities to survey all releases to the environment from hospitals. This will provide a basis for assessing whether to regulate releases from hospitals through individual permits or through regulations pursuant to the Pollution Control Act.

7.6 Farming and forestry

The Government will:

Textbox 7.9 DDT pollution

In 2003, the food and agriculture authorities together with the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority completed an extensive project in which landfills containing DDT sludge in forest nurseries were cleaned up. Sludge containing DDT at a large number of nurseries was dug up and disposed of properly. It was documented at some nurseries that there was no danger of pollution spreading from the contaminated sludge under current land-use regimes.

take steps to achieve the goal that 15 % of food produced and consumed in Norway should be organic by 2015

take steps to reduce the use of agricultural pesticides and reduce the risk of injury to health and environmental damage posed by pesticides

ensure that the systems for the management and use of mineral and organic fertiliser are optimal and consistent with current knowledge at all times. Efforts will continue to keep levels of cadmium in phosphorus fertiliser low.

contribute to research and development on the links between mercury runoff and various types of forestry practices.

Pesticides and organic and mineral fertilisers are the chief sources of hazardous substances from the agricultural sector.

Action plan to reduce the risks associated with the use of pesticides

The agricultural and food safety authorities in Norway have been working actively to reduce the use of pesticides and the risks associated with their use. The action plan for the period 1998–2002 to reduce the risks associated with the use of pesticides was evaluated in 2003. On the basis of an overall assessment of the effects of the measures set out in the action plan, the evaluation group concluded that the level of risk to both health and the environment was reduced by at least 25 % during this period. Despite this positive trend, further improvement is both needed and possible. Among other things, pesticide residues are still found in the aquatic environment. Several of the measures in the action plan are long term, and need to be continued to maintain their effects. An updated action plan was therefore adopted for the period 2004–2008 (see box 7.10). It sets out goals and measures for the use of pesticides. The Government will continue to pay close attention to this area.

Textbox 7.10 Action plan for agriculture (2004–2008)

The action plan lays down the following goals:

to make Norwegian agriculture less dependent on chemical pesticides

to reduce the risk of damage to health and the environment associated with the use of pesticides by 25 % in the period 2004–2008, which would give a total reduction of 50 % in the period 1998–2008.

levels of pesticides in food and drinking water are to be minimised and not exceed limit values

pesticides should not be present in groundwater and levels should not exceed limit values for drinking water

levels of pesticides in streams and other surface water are to be minimised and not exceed values that might result in environmental damage.

Figure 7.6 Pesticide residues are still found in the aquatic environment

Photo: Marianne Otterdahl-Jensen

Indicators for pesticides

A risk indicator has been developed to describe trends in the health and environmental risks associated with the use of pesticides over time. Each substance or preparation is given points on the basis of its intrinsic properties and the calculated risk level. Combining these points with annual quantities of each preparation used yields an overall expression of the risk to health and the environment.

Figure 7.7 Sludge from waste water treatment plants is used as a fertiliser and soil conditioner

Photo: Marianne Otterdahl-Jensen

Taxation system for pesticides

An environmental tax on pesticides was introduced in 1988. In 1999, the system was changed from a flat-rate tax levied as a percentage of the sales value to a tax differentiated according to the hazardous properties of the pesticides. There are several tax classes based on the level of health and environmental risk. The tax rate for each preparation is calculated on the basis of its tax class and normalised application rate. In addition to this change, the general tax rate has been raised several times in recent years. The taxation system introduced in 1999 has helped to shift the use of pesticides towards preparations with a lower risk profile.

Fertiliser and soil conditioner

Sludge from waste water treatment plants is used as an agricultural fertiliser and soil conditioner. Approximately 112 000 tonnes of sludge was used for various purposes in Norway in 2004, and around 51 500 tonnes of this was used in agriculture.

Maximum permitted limits have been established for levels of heavy metals in sewage sludge to be used as a soil conditioner. The producer or seller of the product must take reasonable steps to limit the content of organic ecological toxins, pesticides, antibiotics/chemotherapy drugs or other organic substances that are not naturally present and prevent their presence in quantities that could render use of the product harmful to health or the environment. Producers of sewage sludge are required to report the quantities of product produced and sold, its composition and how it is used. This information is to be filed with the Norwegian Food Safety Authority through the KOSTRA system for reporting local government information. The use of sewage sludge is to be reported to the recipient municipality. As described in Chapter 10.5, the Government will consider measures and requirements relating to waste water and sewage sludge.

Organic fertiliser based on waste/sewage sludge – the need for knowledge

A greater research effort is needed to improve knowledge of the presence and content of ecological toxins in sewage sludge, including the impacts these substances may have on health or the environment, and any measures that should be implemented. The Scientific Committee for Food Safety has been asked to carry out a risk assessment on the use of sewage and on the environmentally hazardous substances it may contain.

Mineral fertiliser

More knowledge is needed of the best possible application of mineral fertilisers in order to reduce the environmental impacts of their use. Mineral fertilisers can contain cadmium. There is no reason to believe that they have any unintentional content of other environmentally hazardous substances. Efforts will continue to keep the cadmium content in phosphorus fertiliser low and not above established limit values. The EU Commission is developing common rules so that a limit value can be established for the cadmium content of fertiliser to apply to all countries in Europe. The rules will be based on a general risk assessment of cadmium, which is expected to be completed by the end of 2006.

Organic food

The Government’s goal is for organic food to account for 15 % of the food produced and consumed in Norway by 2015, and it has initiated interministerial cooperation to achieve this aim. Many organic farming methods developed to reduce the use and discharge of hazardous substances can also be utilised in conventional farming operations.

Forestry

Most of the atmospheric mercury deposited in forested areas is sequestered in the humus layer. Faster decomposition of organic matter mobilises the mercury and increases runoff. Studies undertaken in the Nordic countries and Canada show a clear connection between logging operations involving clear-cutting and disturbance of the soil and mercury runoff to water. There may be a considerable potential for mercury runoff from the humus layer in forests, and this should be further investigated in Norway. The Government will support research on the relationship between mercury runoff and various types of forestry operations in Norway.

7.7 Aquaculture

The Government will:

encourage the use of alternative treatments with less environmental impact and disease prevention strategies in order to reduce the quantities of medicines released by fish farming operations

monitor the consumption of antibiotics in the farming of new marine species and the potential environmental impact of the use of hazardous substances

assess the most suitable instruments, including prohibitions or taxes, for reducing the quantity of copper released from antifouling agents used on net cages.

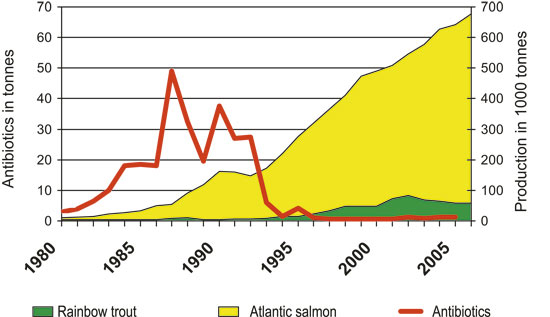

Aquaculture is a large and growing industry in Norway. In 1995, around 220 000 tonnes of farmed salmon and trout was produced, but by 2005 this had risen to around 600 000 tonnes. Aquaculture operations have been established all along Norway’s coastline from Vest-Agder in the south to Finnmark in the north, with the greatest output coming from Nordland and Hordaland counties. These facilities are a source of copper discharges from antifouling agents and of releases of medicines.

Figure 7.8 Salmon and trout farm in Austevoll

Photo: Inge Røskeland

The Government will assess the most suitable instruments, including prohibitions or taxes, for reducing the quantity of copper released from antifouling agents. The purpose of new instruments will be to encourage greater use of other methods, more frequent washing and so on, and to encourage the development and use of replacement products. Antifouling agents are one of the two main sources of copper discharged to water in Norway. The quantity released from antifouling agents has remained stable at around 200 tonnes per year in recent years. Although discharges from net-washing operations have been regulated since the summer of 2005 and alternatives to the use of copper-based anti-fouling agents are being developed, discharges of copper are expected to increase. Substantial reductions in copper discharges will not be achieved without additional measures.

Medicines used in fish farming are to some extent released to the marine environment where they can affect organisms living in the wild. Consumption of antibiotics has been reduced by around 98 % since 1987 – from 50 000 to around 1 000 kg per year (see figure 7.9). But the Government considers it important to continue to monitor consumption and encourage the industry to improve disease prevention methods, particularly for new commercial species.

Although wrasses are being used to some extent for biological salmon louse control, this pest is really held in check by the relatively heavy usage of a few types of delousing agents. Delousing agents can have local environmental impacts, including harm done to crustaceans in the upper water layers around fish farms. These medicines do not bioaccumulate – instead they break down within a short time in the large volumes of water in which they are used. Delousing medicines will continue to be used to prevent salmon lice from affecting the health of farmed salmon and wild salmon alike, but greater use of wrasses in biological louse control would be a good way to reduce the use of chemicals.

Figure 7.9 Antibiotics in fish farming 1980–2005

Source Directorate of Fisheries and Norwegian Food Safety Authority

Textbox 7.11 Norwegians can generally eat more fish

The Scientific Committee for Food Safety has conducted an assessment of the nutritional benefits of eating fish and other seafood compared to the risk of consuming pollutants and other undesirable substances that fish and other marine species may contain. An overall assessment of nutritional and toxicological factors produces the conclusion that Norwegians can generally eat more fish and that the fish consumed should include both lean fish and fatty fish.

The Government will provide a framework for a precautionary approach to management of the aquaculture industry in keeping with current knowledge and will continue to regulate the industry strictly. It is particularly important to continue monitoring consumption of antibiotics, particularly in the farming of marine species. The Government further intends to reduce the risk of resistance to antibiotics by promoting preventive measures instead of an increase in the use of antibiotics.

Salmon and trout production is expected to rise, and farming of marine fish and molluscs and sea ranching are on the rise as well. The Government intends to ensure that further growth in aquaculture continues to produce clean food and reduces the overall environmental pressure from the industry.

7.8 Reduced releases from defence activities and civilian shooting ranges

The Government will:

lay down conditions in discharge permits issued to military and civilian shooting ranges to minimise releases of heavy metals. Requirements to collect ammunition will be introduced where possible. New releases of priority ecological toxins from shooting ranges are to be eliminated by 2020

tighten controls on the military use of white phosphorus by restricting its use to areas where complete combustion is certain to take place, thus ensuring that no white phosphorus is left in the environment.

Shooting at military and civilian shooting ranges releases large quantities of heavy metals into the environment. Releases from shooting by the Norwegian Armed Forces and Home Guard are calculated at around 150 tonnes of lead, 16 tonnes of antimony, 35 tonnes of copper and 6 tonnes of zinc. Civilian shooting releases around 38 tonnes of lead, 5 tonnes of antimony, 18 tonnes of copper and 2 tonnes of zinc. These metals are chiefly deposited in soil berms at the ranges and can lead to local runoff of heavy metals. Since lead shot was banned from shooting ranges in 2002, lead releases have been dropping, chiefly at the civilian ranges. The defence forces will phase lead and antimony out of their small arms ammunition by 2009.

To minimise ongoing releases, the Government will consider the requirements to be applied to the construction of soil berms at shooting ranges and to the control of heavy metal runoff. There are to be no further releases of priority heavy metals (lead, antimony and copper) after 2020.

White phosphorus is used by the military to lay smoke-screens during exercises on various artillery ranges. White phosphorus is an acutely toxic inorganic substance. As long as a normal air supply is present, white phosphorus will continue to burn until completely consumed, in which case it has no environmental impact to speak of. However, if rounds containing white phosphorus land in places where the air supply is restricted, such as in lakes or swamps, it may not undergo complete combustion. In this case, it will remain toxic for many years and pose a serious toxic hazard for animals in the area. The defence forces currently have a self-imposed prohibition against using white phosphorus. The Government intends to tighten controls on the military use of white phosphorus by restricting its use to areas where complete combustion is certain to take place, thus ensuring that no white phosphorus is left in the environment. What is to be done with the white phosphorus already released to the environment will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 10.3.

7.9 Market potential for Norwegian industry, and economic policy instruments

The Government will:

help secure a head start and new market opportunities for Norwegian industry when the environmental technology markets expand

consider stepping up the application of environmental taxes on hazardous substances, for example on releases of copper

consider which instruments are most suitable for reducing the use and releases of triclosan.

The environment as a growth industry

Stricter international rules on releases of hazardous substances, greater environmental awareness on the part of consumers and enterprises, and other factors have created considerable market potential in new environmentally sound technology. The OECD estimates the world market for environmental technology at NOK 4 trillion per year. Annual growth in this market is 5 – 20 %, higher than many other technology markets.

One of the Government’s objectives is to ensure that Norway is at the forefront in environmental technology. There are many good examples of Norwegian companies that are at the leading edge in this area, including in the development of technologies to reduce releases of hazardous substances. This has provided economic growth and created jobs in Norway. Environmentally sound technology is promoted through regulatory measures and through research and development. The Norwegian Pollution Control Authority has also established a project to promote the development, use and export of environmental technology, with the construction industry as one of the priority areas.

Increased use of environmental taxes on hazardous substances

Economic policy instruments can be one good alternative to direct regulation as a means of preventing environmentally harmful activity. Economic instruments such as environmental taxes provide a direct signal to producers and consumers of the environmental cost of pollution. Environmental costs included in the prices of polluting forms of production and products can influence choices of products and services. Economic instruments also provide incentives for manufacturers to choose cleaner technologies and systems/equipment for controlling emissions, to use more environmentally sound raw materials and to produce more environmentally sound products. Economic instruments will also provide incentives for continuing to develop environmentally sound technology and reduce emissions below statutory requirements.

Environmental taxes have for example been introduced on pesticides. The taxation system has helped to shift consumption towards preparations that pose less risk (see Chapter 7.6).

Environmental taxes provide incentives for taking effective steps to reduce emissions across a broad range of enterprises, such that enterprises where the costs of reducing emissions are lowest make the greatest relative cuts in their emissions, thus reducing pollution at the lowest possible cost. Another effect of environmental taxes is that the environmental costs involved in production translate into higher prices for products and services, thus influencing consumers to make environmentally sounder choices.

The Government will step up the use of environmental taxes on hazardous substances and will conduct assessments of appropriate candidates for taxation. The Government proposes to assess new instruments targeting copper, which may include environmental taxes (see sections 7.7 and 9.3.5), and triclosan (see section 9.3.4).

7.10 Transport

The Government will:

assess by 2008 the need for national measures to reduce releases of PAHs from transport

take part in efforts to ensure the safe transport of hazardous substances

strengthen the emergency response capability for dealing with accidents involving environmentally hazardous substances and dangerous goods being moved by road, rail, sea or air transport

step up efforts to introduce packaging for hazardous substances that is safe for industrial and consumer purposes

work towards the entry into force of the International Convention on the Control of Harmful Anti-fouling Systems, and seek to ensure that the shipping industry

adheres as far as possible in practice to IMO’s existing guidelines on the recycling of ships

implements IMO’s revised regulations on chemicals.

Releases from road traffic

Hazardous substances released by motor vehicles come chiefly from exhaust gases and from wearing parts such as brake linings and tyres. Substances in exhaust emissions include mercury, copper, benzene, PAHs, arsenic and chromium.

Figure 7.10 Vehicle exhaust contains hazardous substances

Photo: Marianne Otterdahl-Jensen

Emissions standards for new vehicles are established internationally and have been tightened up over the past 10–15 years. These standards deal chiefly with emissions of NOx and particulate matter, but will also reduce emissions of hazardous substances in exhaust. It takes a fairly long time to replace the entire fleet of motor vehicles, so it will be some time before the new standards have much effect.

Implementation of EU legislation that requires new emission measurements will lead to better information on concentrations of PAHs. Measurements will start in 2007 and will reveal whether it will be necessary to implement national measures.

The health impact of hazardous substances released by wear on asphalt, brake linings and tyres is greatest in urban areas. High concentrations of PAHs in asphalt have been found in some places. Tyres contain heavy metals (lead, copper, zinc) and organic ecological toxins such as octylphenol and PAHs. The EU decided in June 2005 to restrict the maximum concentration of PAHs in the HA oils used in tyres. This applies to new tyres of all types and will enter into force on 1 January 2010. The Government intends to further clarify the impact of road traffic on health and the environment and will consider whether to introduce further measures on the basis of its findings.

Textbox 7.12 Brominated flame retardants in tunnels

Insulation materials in tunnels may contain brominated flame retardants. It is important to determine whether this is the case when replacing materials in tunnels because waste materials may be classified as hazardous waste if they are found to contain brominated flame retardants. They may also be found in adjoining concrete materials and in seepage water.

Transport of dangerous goods

Transport of dangerous goods is a potential source of major spills of hazardous substances, and there is a risk of theft and misuse of dangerous goods. Broad new security provisions on the transport of dangerous goods have been implemented at national and international levels. To maintain a level of risk acceptable to society, priority will be given to such policy instruments as collaboration with other authorities and important user groups, legislative action, publicity and information, training and inspection and enforcement.

The Directorate for Civil Protection and Emergency Planning has issued guidelines on how to implement the security measures together with a model security plan for enterprises involved in transport of dangerous goods. These guidelines will also be of use to other enterprises that handle dangerous chemicals.

Whenever dangerous goods are handled at seaports, railway facilities or other cargo handling terminals, there is always the risk that an accident may happen. The Government intends to prepare a systematic overview of the risks associated with the transport of dangerous goods and identify any needs for preventive or emergency planning measures to reduce these risks to an acceptable level. Among other things, the Government will:

consider whether accident data and information on the quantities of dangerous goods transported on different roads and by different means of transport can be utilised in assessing overall risk reduction measures

review all administrative agencies and legislation relevant to the transport of dangerous goods in Norway from the perspective of overall civil protection, and ensure that transport of dangerous goods takes place in a way that maintains the highest possible level of civil protection across all transport sectors. This work will be based on the results of a research project on risk levels and the roles played by various actors involved in the transport of dangerous goods, which is part of the research programme Risk and Safety in Transport (RISIT)

take steps to improve the emergency services’ expertise and ability to respond effectively to accidents involving dangerous goods, for example by facilitating exercises.

Releases from shipping

Shipping represents a potential for acute releases of dangerous or polluting substances. Moreover, ships discharge a number of pollutants to sea and air in the course of normal operations. When it comes to acute releases, the Government intends to continue the work on maritime safety and the oil spill response system presented in a recent white paper on the subject (Report No. 14 (2004–2005) to the Storting).

Shipping is regulated by international conventions within the framework of the International Maritime Organization (IMO). Discharges from tank cleaning or de-ballasting operations on board oil and chemical tankers are regulated by Annex I and II respectively of the MARPOL Convention. These annexes have recently been revised, and strict new amendments enter into force on 1 January 2007.

The revised annexes apply substantially tougher rules to discharges of chemicals in particular. The overriding principle is that no chemicals may be transported in bulk by chemical tankers unless the chemicals have first been classified with regard to safety and the environment. The new regulatory provisions only permit the release of cargo residues that are considered to present little environmental hazard. The Government will see to it that the new regulations are implemented promptly.

Organotin compounds (especially TBT) do considerable damage to the aquatic environment. On 5 October 2001, IMO therefore adopted the International Convention on the Control of Harmful Anti-fouling Systems on Ships (the Anti-Fouling Convention). The convention prohibits the application of organotin compounds in anti-fouling systems to any ship from 1 January 2003, and it prohibits the presence of such compounds on ships from 1 January 2008. The Government will work towards the entry into force of the convention.

7.11 Acute pollution – prevention and emergency response measures

The Government will:

improve the regulatory framework to ensure that any acute and uncontrollable releases of chemicals do not pose an unacceptable risk to third parties or to the environment

give priority to the effort to establish an effective emergency response system to limit damage to life, health and the environment in the event of acute releases of chemicals

take steps to strengthen collaboration between all agencies involved in emergency response efforts in order to promote effective responses to accidents involving hazardous substances

see to it that guidelines are established for the proper and effective utilisation of Civil Defence resources by emergency services in the event of major chemical accidents.

7.11.1 Prevention of acute pollution and accidents

Enterprises that handle hazardous substances

Society must require preventive measures to be taken during the handling of hazardous substances so that they do not pose unacceptable risks to life, health or the environment. Such measures must apply both to incidents that may occur in the normal course of operations and to deliberate undesirable actions. The Directorate for Civil Protection and Emergency Planning will incorporate security provisions in its revision of provisions relating to preventive measures in enterprises that handle hazardous substances.

The Fire and Explosion Prevention Act regulates preventive and emergency response measures in connection with the handling of flammable substances, explosive substances, substances under pressure, and the transport of dangerous goods by road or rail. One of its main objectives is to set requirements for preventive measures with a view to safeguarding third parties against the adverse consequences of accidents involving the hazardous substances regulated by the Act. At present, the Act provides the legal authority for provisions regulating the storage of sulphur dioxide gas, but not for provisions regulating the storage of sulphuric acid. A spill of a large quantity of sulphuric acid can create a cloud of sulphuric acid vapour on contact with water, as happened in Helsingborg in Sweden in May 2005. The Government therefore intends to expand the definition of hazardous substances in the Fire and Explosion Prevention Act to include substances that undergo dangerous reactions with other substances, and will soon submit a bill to this end. This will provide a stronger legislative basis for reducing risks to third-party life and health.

Major-accident hazards – the Seveso Directive

The EU’s Seveso Directive lays down special requirements for enterprises using or producing chemicals that are considered particularly dangerous and where accidents could cause major injury to persons or major damage to property or the environment. The directive names specific chemicals and groups of chemicals, and it requires operators to provide notification and reports to the competent authorities. Norway has implemented the requirements of this directive in its Regulations relating to major-accident hazards. The purpose of these regulations is to prevent major accidents and limit the damage caused by any such accidents that do occur. The Directorate for Civil Protection and Emergency Planning has been given the responsibility for coordinating the authorities’ actions to follow up the major-accident hazard regulations, and a secretariat has been established for this purpose. Several major accidents at industrial establishments in other countries that come within the scope of the Seveso Directive have prompted the Government to review experience gained in other countries and see how it applies to Norway.

7.11.2 Response to acute pollution

Effective communication of information on hazardous substances, their properties and danger zones to emergency response personnel is essential in limiting loss of life and damage to health and the environment. This is why it is important for the authorities involved – the Directorate for Civil Protection and Emergency Planning, the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority and the Norwegian National Coastal Administration – to make a joint evaluation of effective ways of achieving this for all types of incidents.

It is essential that all who are involved in dealing with accidents involving chemicals have the expertise and equipment necessary to make the right decisions and take appropriate action. The Norwegian Civil Defence is a very important resource in the event of a major incident involving spills of chemicals beyond the capacity of the emergency services. The Government will see to it that good guidelines are developed for the emergency services on how to utilise Civil Defence resources properly and effectively when dealing with major accidents involving chemicals.

The Government response to acute pollution

The Pollution Control Act assigns primary responsibility for the emergency response to acute pollution to the enterprises that handle such chemicals. Secondary responsibility for the emergency response system lies with the local authorities. The Act requires the state to provide for the necessary emergency response system to deal with major incidents of acute pollution that are not covered by private or municipal emergency response systems. The Norwegian National Coastal Administration is responsible for the state emergency response system for acute pollution. Response capabilities are dimensioned on the basis of environmental risk and emergency response analyses. As in other emergency planning segments, they are not based on worst case scenarios or multiple simultaneous incidents. The state’s emergency response to acute pollution is largely based on coordination with other authorities, organisations and institutions. It is mainly designed to deal with major oil spills from shipping. State emergency response supplies and equipment is stored in 15 depots along the coast and in Svalbard. The Norwegian National Coastal Administration also has four small oil spill response vessels and one surveillance airplane. Oil spill response equipment is also carried aboard a number of Coast Guard vessels.

The state’s first line of response to accidents involving chemicals is to provide technical advice. A nationwide emergency response network consisting of expert organisations and institutions has been organised to provide assistance in connection with incidents that occur during land transport of dangerous goods. This national network is also linked up to a European emergency response network covering 14 countries. And the Norwegian National Coastal Administration’s 24-hour emergency response line ensures that in the event of an accident involving chemicals, assistance from experts from the chemical industry and relevant institutions is quickly available at the scene of the accident.

The role of the Norwegian National Coastal Administration is to ensure that action is taken by the polluter, by the local authority or by the appropriate state agency to deal with acute oil or chemical pollution, and that the steps taken are sufficient to prevent and limit environmental damage.

Analysis of shipping along the Norwegian coast in general, and the transport of chemicals along the coast and in Norwegian ports in particular, indicates that up until 2015, the general environmental risk will increase with the growing volume of oil transport by sea. The risk to the environment from the transport of chemicals by sea through Norwegian waters is considered to be small. There are some geographical areas where risks from the transport of chemicals by sea are somewhat higher, and special accident prevention measures such as vessel traffic service centres and special rules for navigation and passage have been implemented in these areas.

Industry response to acute chemical pollution

Enterprises that handle hazardous substances are required to establish their own emergency response systems in compliance with provisions of the Pollution Control Act, the Fire and Explosion Prevention Act and the Civil Defence Act. The major-accident hazard regulations also lay down specific requirements for emergency response systems in industrial enterprises. The authorities responsible for administration of the legislation mentioned above are also the supervisory authorities for these requirements. Emergency response systems and contingency plans must focus on limiting harmful impacts on humans, the environment and property and must be possible to implement immediately in the event of an accident. Plans must be reviewed and updated regularly, and enterprises are required to hold exercises, both on their own and in collaboration with the external public emergency response agencies. The 10 largest chemical-handling enterprises in Norway have together with the Rescue Coordination Centre in South Norway, the 335th Air Wing and the Norwegian Industrial Safety and Security Organisation established a joint arrangement for mutual assistance in the event of accidents.

Intermunicipal acute pollution control committees

The public-sector emergency response to accidents involving dangerous goods and chemicals is based on the local fire departments providing the front-line response. Most fire departments are fully competent to deal with the most common flammable substances, but many hazardous substances require special equipment and procedures. The municipal emergency response system is organised in 34 regions administered by intermunicipal acute pollution control committees. This intermunicipal system is dimensioned to deal with acute spills of chemicals of the sort that can occur in connection with ordinary activity in the region in cases where no private-sector emergency response system has been established for this purpose. In most of the regions, the host fire departments are relied on for the specialist expertise and equipment for dealing with accidents involving dangerous goods or substances.

Responsibility of local, regional and national authorities for external emergency response planning

The EU’s Seveso II Directive requires the competent authorities to prepare local and regional external emergency plans providing for the necessary measures in the event of accidents, and that they are tested and exercises are held. Norwegian enterprises to which the major-accident hazard regulations apply must comply with the same requirements. Enterprises subject to reporting requirements are to provide the public authorities with the information they need to prepare external emergency plans.

The Government expects all those involved in this work (including the public health authorities) to have established emergency response plans and to hold exercises so that they are prepared to deal with any incidents The Government will strengthen cooperation between all actors, both public and private, to ensure the best possible response to accidents involving chemicals.