3 Development policy at a crossroads

Chapter 2 presented current challenges and crises, and this chapter turns to an analysis of key features of the system for international development cooperation. The cost of meeting the SDGs in developing countries ranged from USD 2,500 to USD 3,000 billion annually.40 After the pandemic, the OECD estimated that this gap may have increased to USD 4300 billion annually.41 The SDGs, and the timeframe set to reach them, are extremely ambitious, and yet the funding gap is increasing. Moreover, an increasing amount of aid is directed toward acute needs and humanitarian efforts, including aid to fragile states with ongoing violent conflicts. At the same time, global challenges have grown to become a key priority, and an increasing proportion of ODA is being used to fund action on climate change, pandemic preparedness and response to conflict and migration. This is happening at the same time as ODA is expected to deliver on its existing mandate of economic growth and welfare in developing countries.42 As we discuss below, development assistance can serve its purpose and do so effectively. Nevertheless, the amount of ODA allocated to the countries most in need is too low at the same time as new goals and challenges have been added to the international and Norwegian aid agenda, thereby stretching already limited funding ever more thinly at the same time as more funding is needed.43

Boks 3.1 OECD Development Assistance Committee

The OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) is an international forum for many of the largest providers of aid.

The overarching objective of the DAC is to promote development cooperation and other relevant policies to contribute to the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, poverty eradication, improvement of living standards in developing countries, and to a future in which no country will depend on aid.

In order to achieve this overarching objective, the Committee shall amongst others: a) monitor, assess, report and promote the provision of resources that support sustainable development by collecting and analysing data and information on ODA and other official and private flows, in a transparent way; b) review development cooperation policies and practices, particularly in relation to national and internationally agreed objectives and targets, uphold international norms and standards, protect the integrity of ODA, and promote transparency and mutual learning; c) provide analysis, guidance and good practice to assist the members of the DAC and the expanded donor community to enhance innovation, impact, development effectiveness and results in development cooperation.44

In this chapter, we will

- describe how the international development cooperation system originally established to reduce poverty and contribute to economic growth in poor countries, are increasingly being used to address a series of global challenges, particularly related to climate change, conflict, and refugees

- show how this funding gap is exacerbated by the fragmentation of the architecture of international aid, which no longer appears fit for purpose

- show how Norwegian development cooperation reflects this international trend, despite high volumes of aid

- show that international development cooperation has been characterised by a (top-down) donor-recipient relationship and is ripe for modernisation

3.1 International aid is important but not sufficient

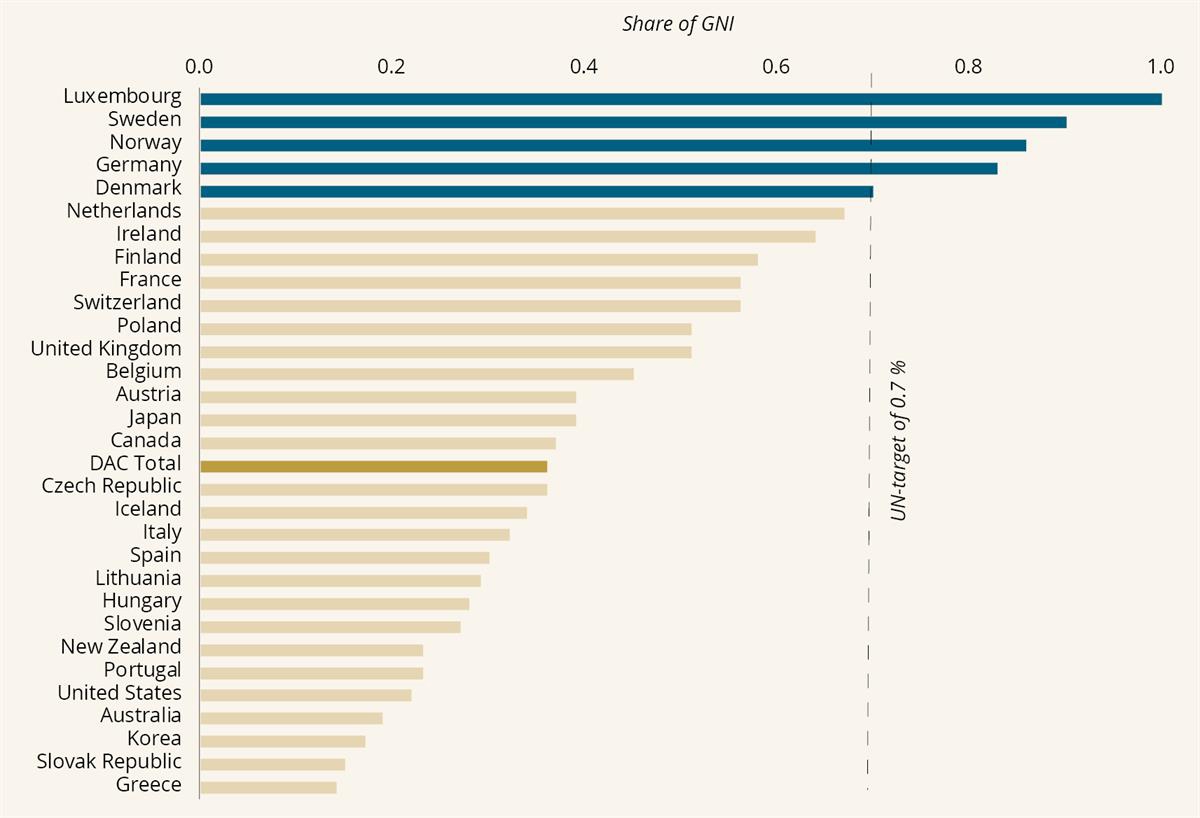

ODA is the key international measure of official and concessional flows of resources to developing countries. Rich countries agreed to commit to a GNI target for development aid as early as the 1950s, and in 1970 the target of 0.7 % of GNI to ODA was adopted.45 The 0.7 % target was reaffirmed at the 2015 Conference on Financing for Development in Addis Ababa.46 However, only a few provider countries meet the target (see Figure 3.1). ODA as a share of GNI has stagnated at the level reached in 2005, at around 0.3 % for all DAC donors combined. However, due to increased refugee costs in donor countries and aid to Ukraine in 2022, it rose to 0.36 %. This is the highest ODA GNI share since 1982.

Total ODA from DAC members in 2022 was USD 204 billion.47 If all provider countries had complied with the UN commitment and provided 0.7 % of their GNI as ODA, total ODA would have reached USD 390 billion, i.e., almost double.

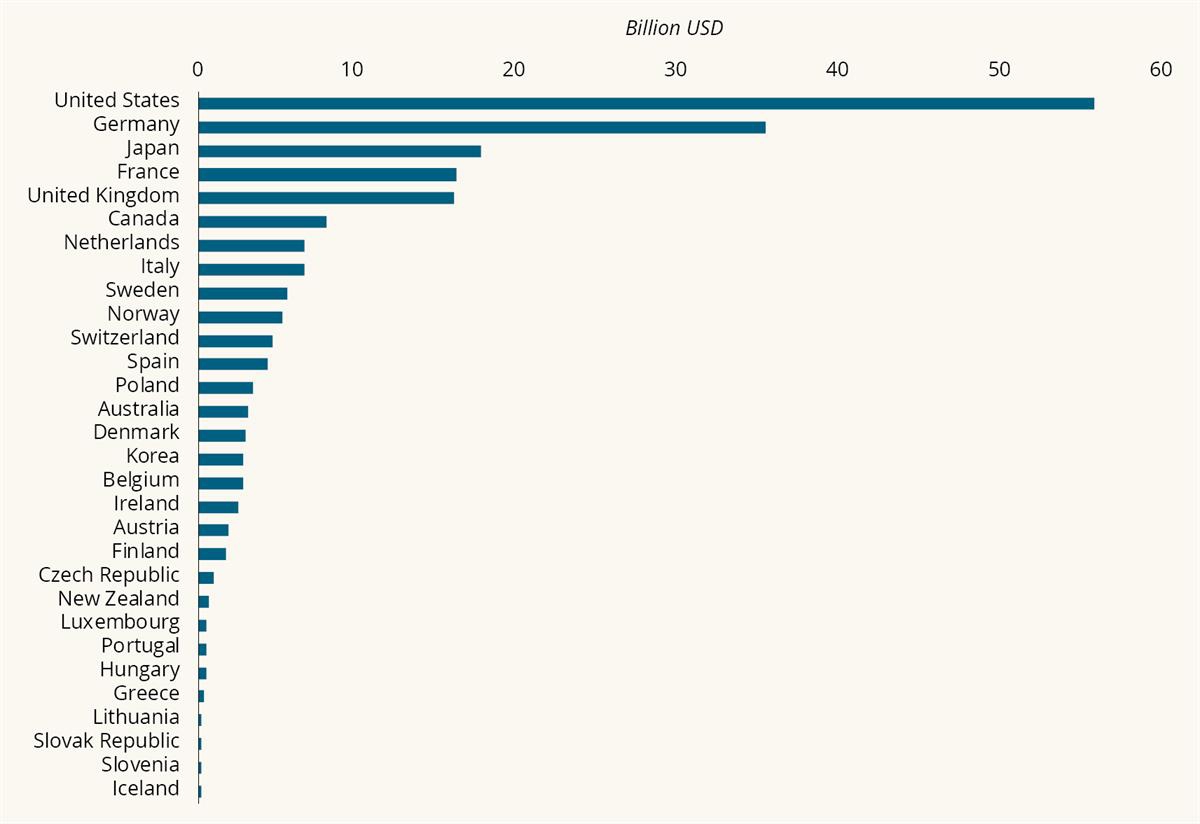

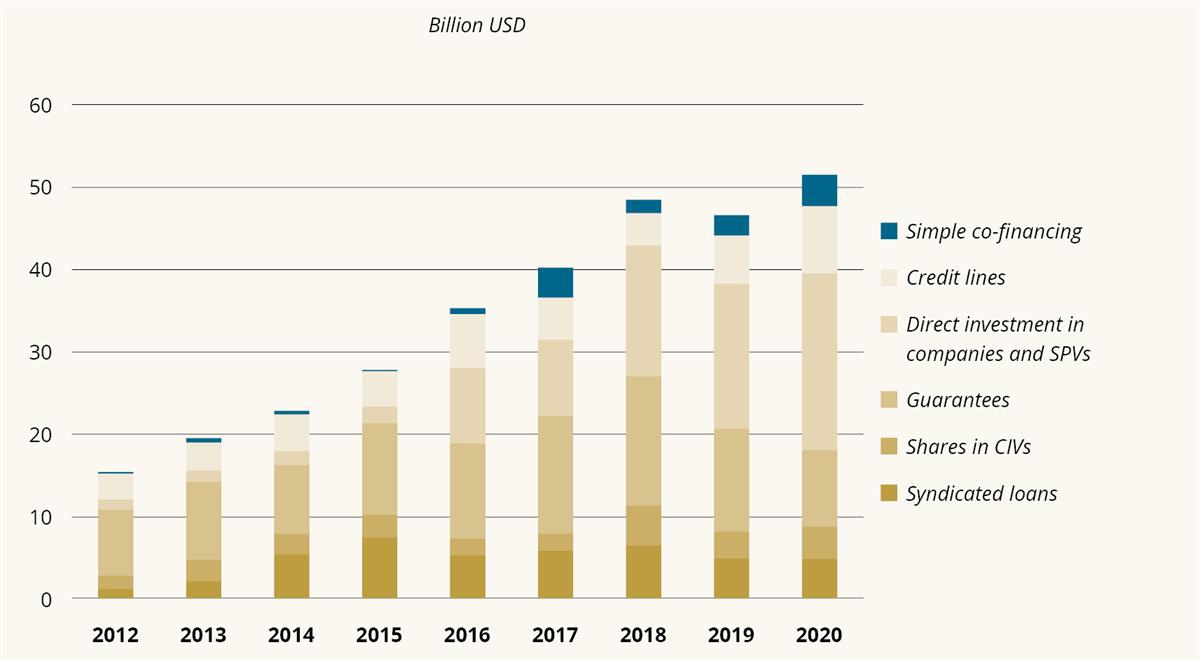

The international donor community has for years envisioned that more private capital would flow to developing countries, narrowing the funding gap. This has particularly been the case when it comes to climate finance. Mobilising private investments by official development finance interventions is a key component of the funding strategy to achieve the SDGs and climate targets. There has been an increase in mobilised private capital, but this increase has stagnated, and the level is lower than expected. According to the OECD, almost USD 50 billionwas mobilised annually between 2018 and 2020.48 Multilateral development banks are the largest actors, mobilising 69 % of the total in 2020. Bilateral actors accounted for 25 %, through their development finance institutions.

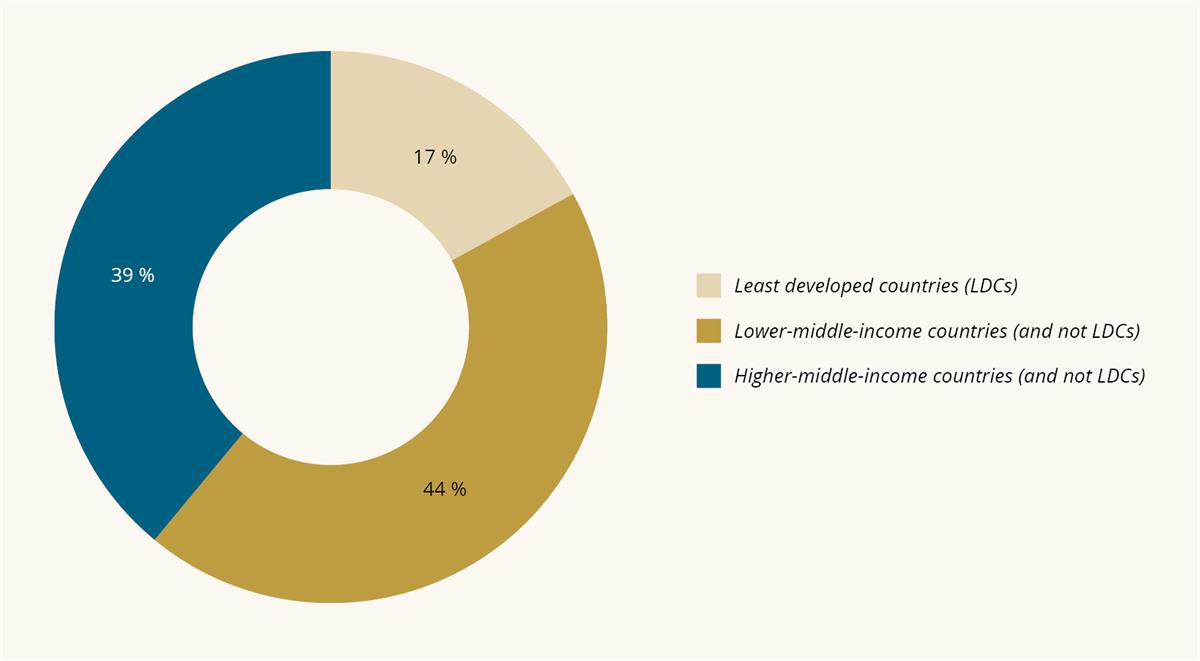

Of total mobilised private finance in 2020 only 17 % was provided to the least developed countries. 44 % was mobilised to lower-middle-income countries and 39 % to higher-middle-income countries. More than 30 % of mobilised private capital targeted emission reductions and/or climate adaptation, most of it going to emission reduction investments. The largest share (42 %) in 2020 was mobilised by direct investments in companies, while guarantees accounted for 18 %.

Figur 3.1 ODA from members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee in 2022

Note: Preliminary figures for 2022, reported through the Advance Questionnaire (ADV).

Source: OECD n.d. Total Flows by Donor (ODA + OOF + Private) [DAC1]. OECD.Stat. Available athttps://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLE1.

Figur 3.2 Mobilised private finance mainly targeted middle-income countries

Note: The pie chart shows an average for 2018–2020, and only shows mobilised private financing going to individual countries. Least developed countries (LDCs) now comprise 46 countries that are mainly low-income countries (26 out of 28 low-income countries) and lower-middle-income countries. In the figure, the two low-income countries that are not LDCs are included as LDCs.

Source: OECD 2022. Mobilisation. OECD.Stat (retrieved November 2022). Available at https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=DV_DCD_MOBILISATION.

DAC members are not alone in providing financial support for the economic development and welfare of developing countries. Many other donor countries have long traditions of doing so. One example is Turkey, which was among the top 10 donors globally in 2022 and provided aid equivalent to 0.79 % of GNI.49 In total, countries outside the DAC reported USD 17.8 billion to the OECD in 2022.50 In addition, it is estimated that over USD 7 billion in aid is distributed by a group of middle-income countries that do not report ODA, of which China, which has become one of the most important providers of development funding internationally, is the largest donor.51

Another key trend is the proliferation of donors and development mechanisms. Between 2000 and 2019, the number of public donors increased from 47 to 70, while the number of development entities increased from 191 to 502.52 The increase in development mechanisms, particularly in the number of multilateral mechanisms, amplifies the risk of overlapping efforts and often increases the number of intermediaries. This reduces the resources that reach the end user. At the same time, the average size of donations has dropped from USD 1.5 million to USD 0.8 million.53

The OECD has expressed concern about the impact these trends have on the effectiveness and quality of aid.54 Principles for aid effectiveness (see Chapter 5) emphasise precisely the importance of coordination, concentration, long-term perspectives, and national ownership in partner countries. All of this has become less attainable due to the proliferation of actors and mechanisms, and also because of an increase in emergency relief, which typically has to be channelled through non-state actors.

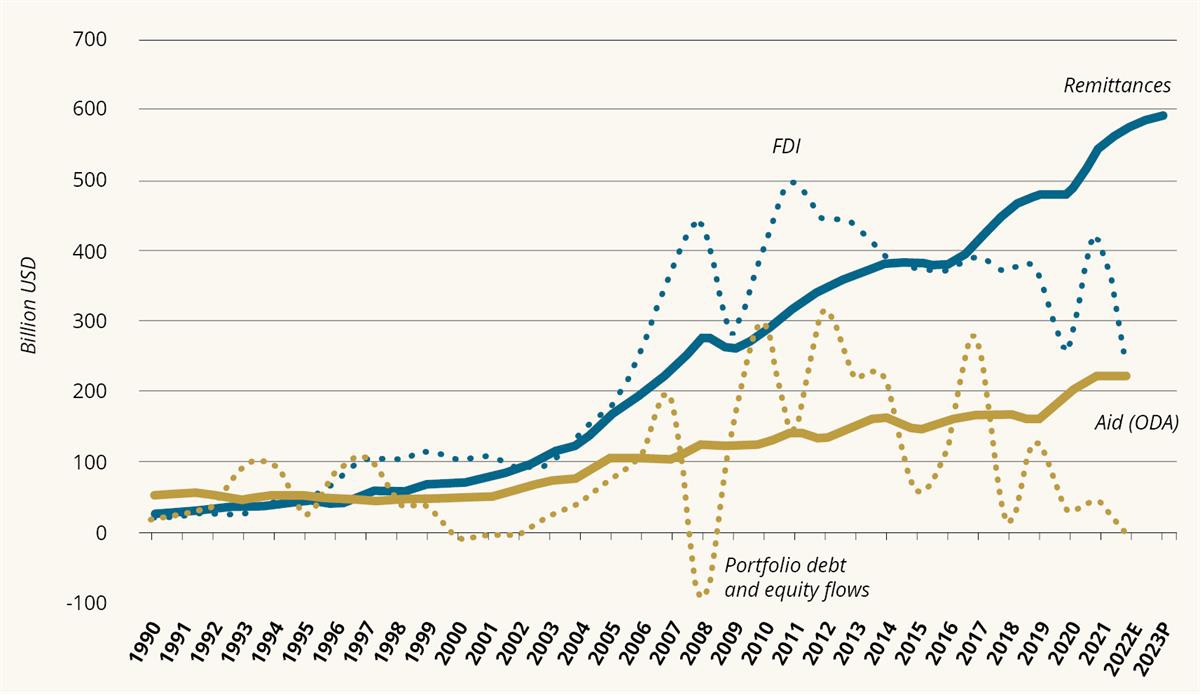

ODA makes up only part of the total international financial flows for sustainable development in developing countries. Remittances from diaspora communities in particular have become a major source of external funding. For developing countries, the level of both money transfers and foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2021 was well above ODA in total volume (see Figure 3.3).55

Figur 3.3 External financial flows to developing countries

Note: Financial flows to low- and middle-income countries, excluding China. FDI = Foreign Direct Investment. Remittances = remittances from diaspora. E = estimates, P = projections.

Source: Dilip Ratha, Eung Ju Kim, Sonia Plaza, Elliott J Riordan, Vandana Chandra and William Shaw. 2022). Remittances Brave Global Headwinds. Migration and Development Brief 37. Washington, D.C. KNOMAD-World Bank; World Bank. 2022). World Development Indicators (last updated April 2022). Available at https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

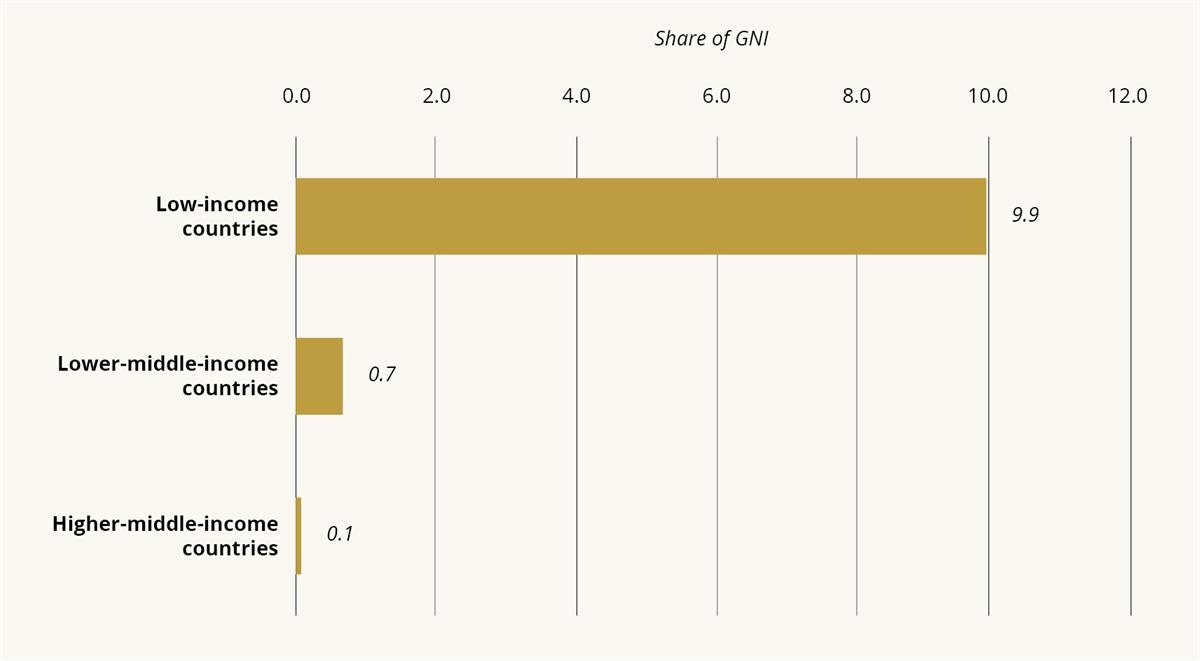

The picture is quite different if we distinguish between low-income, lower-middle-income and higher-middle-income countries. For the poorest developing countries, access to capital is limited and volatile, and ODA is a crucial source of external financing (Figure 3.4). Between 2017 and 2021, low-income countries on average received ODA equivalent to 9.9 % of their GNI, compared to a 0.7 % share for lower-middle-income countries.56

This is why the UN urges donor countries to allocate at least 0.15 %– 0.20 % of their GNI to the world’s least developed countries, and why the 2015 International Conference on Financing for Development in Addis Ababa encouraged donors to set a target of at least 0.2 % of GNI for LDCs.57 However, like the 0.7 target, the LDC target is not met by the international donor community. In recent years, the average for DAC member countries has been around 0.09 % of GNI.58 Norway is one of the few exceptions. In 2021, Norway’s contribution to LDCs was 0.25 % of GNI, representing 27 % of its total aid contribution.59

Figur 3.4 ODA represents a large proportion of GNI in low-income countries

Note: Official development assistance (ODA) as a proportion of the beneficiary countries’ gross national income (GNI), by income group. Average for 2017–2021.

Source: World Bank 2023. World Development Indicators (last updated 3 January 2023). Available at https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

3.1.1 More international aid to address crises and global challenges

Throughout ODA’s sixty-year history, it has been the most stable source of external funding for developing countries and measured in USD, there has been a significant increase in international aid over time. During the Covid-19 crisis in 2021, ODA reached its highest levels, with USD 186 billion, a real term increase of 8.5 % from the previous year. However, the scale of additional needs generated by the Covid-19 crisis is far greater than the increase in international ODA. In real terms, ODA only increased by 0.6 % when excluding the cost of Covid-19 vaccines in 2021, including surplus vaccines donated from donor countries.60

If all Covid-19-related aid is excluded, gross bilateral ODA actually fell in 2020 except for ODA to upper-middle-income countries.61 International aid statistics for 2022 show that the war in Ukraine exacerbates the diversion of international aid away from Africa and the poorest countries. Aid earmarked for Ukraine amounted to USD 16.1 billion in 2022, equivalent to 7.8 % of total ODA from the DAC countries. An additional USD 10.6 billion was given to Ukraine from EU institutions, representing 38 % of their total aid. Eventually, the reconstruction of the Ukrainian state will also have to be partly financed by aid funds. The war in Ukraine will therefore affect the international aid system for a long time to come.

Refugee costs in donor countries constitute a significant and varying proportion of international aid.62 Refugee expenditure in international aid was historically high in 2016, accounting for 11 % of total ODA. Expenditure was halved by 2021, but increased significantly again in 2022 to 14.4 %, as a result of the flow of refugees from Ukraine. Preliminary figures for 2022 show that a large proportion of the increase in aid budgets can be attributed to support to Ukraine and related refugee costs in donor countries. At the same time, we see a decrease in the proportion of aid to other countries, and a real term decline in aid earmarked for Africa of 7.4 % from 2021 to 2022.

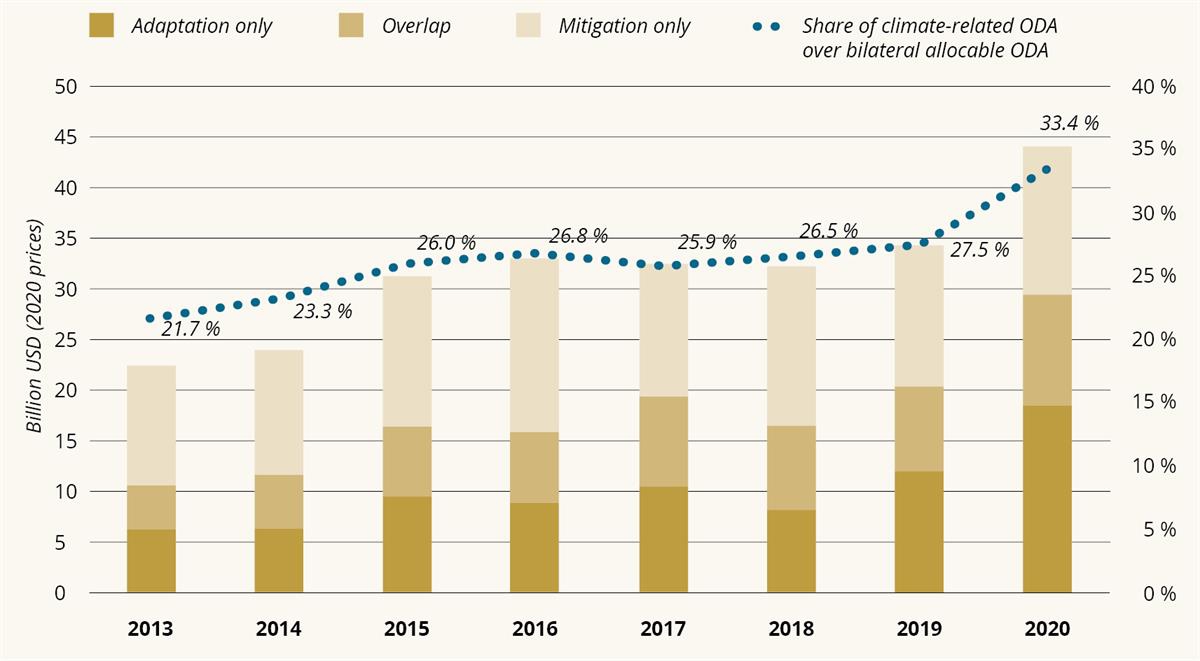

The climate crisis has increasingly affected the allocation of international aid and is likely to become an even more important consideration in the future. From 2018 to 2020, a total of USD 113.1 billion in climate funding was reported as ODA. This includes both climate adaptation and emission reductions.63 Most of the funding has gone to emission reductions, but the proportion allocated to climate adaptation is on the rise. The increase in funding for climate action contributes to a shift in aid from the poorest countries to middle-income countries. Between 2018 and 2020, just under a quarter of climate aid went to countries in Africa, while Asia received just under half (43 %).64 While there is broad international recognition that development and climate must be considered together, the figures show that prioritising climate has an impact on the allocation of international aid for other purposes, such as economic growth and poverty reduction, and that climate funding is largely covered by ODA budgets.65

Figur 3.5 An increasing proportion of international aid is spent on climate

Note: Figures are on aid from members of the OECD DAC with climate change mitigation, climate adaptation or both as an objective. The columns show the agreed amount of funding in contracts containing climate goals in the applicable year. The trend line shows climate-related aid as a proportion of total bilateral allocable ODA in the applicable year. Bilateral allocable ODA includes all aid except core support to multilateral organisations, general budget support, debt relief, and expenditure in the donor country, such as calculated student support, information support, refugee costs and administration, as these by definition, cannot by tracked using markers for climate change.

Source: OECD. 2022). Climate-Related Official Development Assistance: A Snapshot. Paris: OECD Publishing.

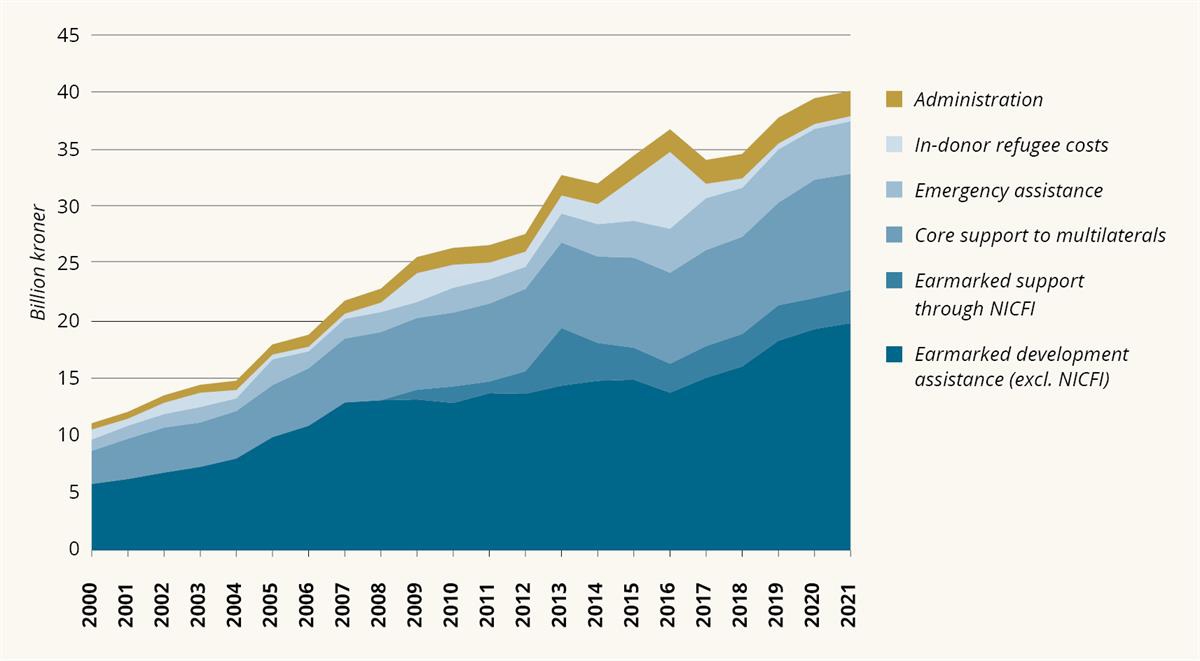

3.2 Norwegian aid: substantial but fragmented

Norway is one of five members of the OECD DAC that achieves the UN target of 0.7 % of GNI as ODA.66 Norway has remained above 0.7 % of GNI since the mid-1970s and has been at around 1 % since 2009. In 2022, however, this percentage fell to 0.86 %. From 2000, the amount of Norwegian aid increased in line with the increase in GNI, from NOK 11 billion to almost 50 billion in 2022. Priorities and thematic areas have changed over time, due to changes in political priorities of new issues (climate in particular) and responses to international crises, as we discuss below.

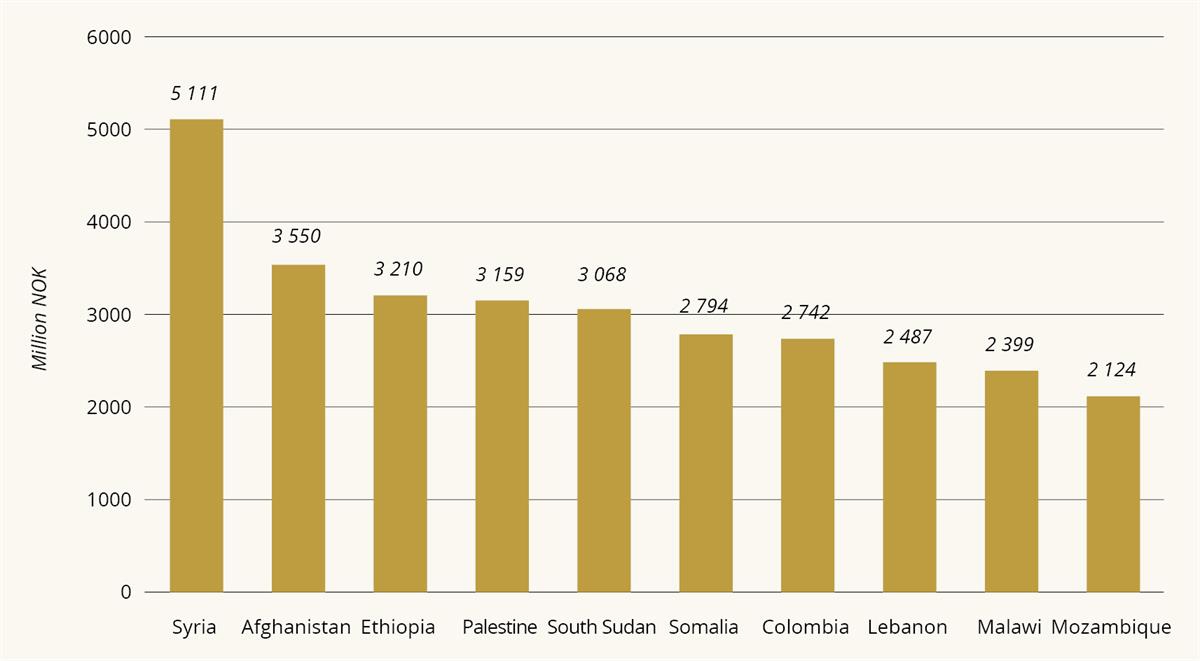

International crises have had a significant impact on Norwegian aid. For example, the war in Syria brought an influx of refugees to Norway: In 2015 11 % of Norwegian aid went to ODA-approved refugee costs in Norway, rising to 18 % in 2016.67 Moreover, between 2016 and 2021, Syria was the largest recipient of Norwegian aid, even though it is not one of the Government’s seventeen priority ‘partner countries in development cooperation’.68 This shows the influence that conflict and humanitarian crises have on the disposition of aid.

In 2022, as a result of the war in Ukraine, refugee expenditure accounted for 9 % of total Norwegian aid. Since 2022, the war in Ukraine has changed the geographical disposition of Norwegian aid and this will continue for some years to come. Ukraine is the largest recipient of Norwegian aid, while the proportion of Norwegian aid that goes to countries in Africa and the LDCs is declining. The same trend can be seen in the preliminary figures for international aid.

Norwegian health aid remained stable for a long time, but from 2019 to 2021, aid earmarked for health more than doubled, from NOK 2.1 billion to NOK 4.6 billion. This can solely be explained by increased expenditure on Covid-19 tests, vaccines and protective equipment for health workers, as well as measures to combat the disease and Covid-19 mortality, and to control the extent and consequences of the pandemic.

Figur 3.6 Composition of Norwegian aid

Note: Total Norwegian aid, 2000–2021.

Source: Norad n.d. Norwegian aid results. Statistics and results of Norwegian development aid. Available at https://resultater.norad.no/no.

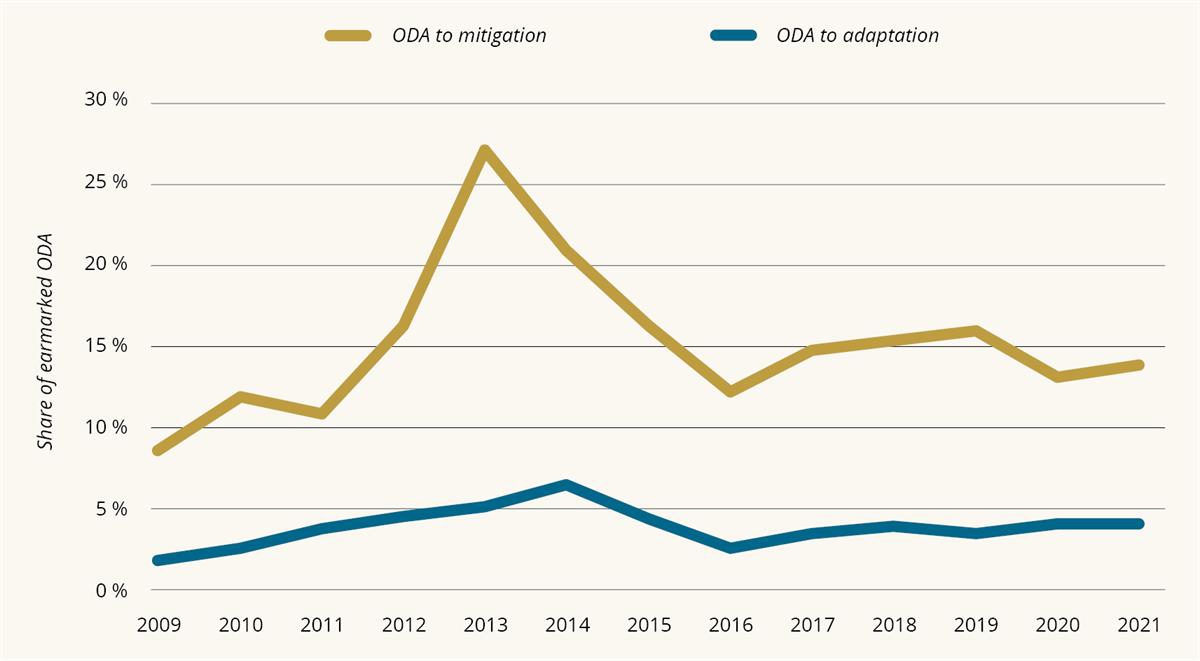

From 2000, climate aid – mainly emission reductions – increased significantly (Figure 3.6).69 A large proportion of this – a total of NOK 34 billion in the period 2009–2021 – is from Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative. In 2021, total ODA-approved climate aid from Norway amounted to NOK 6.4 billion. This corresponds to 16 % of the total aid.

Figur 3.7 Most climate-related aid went to emission reductions

Note: The proportion of climate-related aid of Norwegian earmarked aid, excluding aid through Norfund. This includes 100 % of the disbursed amount under agreements that had climate change mitigation or adaptation as their principal objective, as well as 40 % of the disbursed amount under agreements that had these as secondary objective – in line with the Norwegian method. Earmarked aid: all aid except for administration and core support for multilateral organisations.

Source: Norad n.d. Norwegian development aid. Statistics and results of Norwegian development aid. Available at https://resultater.norad.no/no.

At COP 26 in Glasgow, Norway committed to doubling its total annual climate funding from NOK 7 billion in 2020 to NOK 14 billion by 2026.70 Currently, the vast majority of Norway’s climate funding is provided for under the aid budget. How the increase to NOK 14 billion by 2026 will affect future Norwegian aid depends on how much of the increase is financed by ODA on the one hand, and how much is financed by Norfund’s (including the Climate Investment Fund’s) recycled investments and mobilised private capital estimates on the other. Absent a corresponding increase in overall ODA, however, this increase in climate financing will represent a significantly larger proportion of Norwegian aid, thus raising concerns of whether climate financing really will be additional.

3.3 Channels and partners in Norwegian aid

Another notable change in Norwegian aid over time is the choice of channels. In 2000, 14 % of aid went to governments and the public sector in developing countries, while this figure was just under 2 % in 2021. At the same time, the use of multilateral organisations has increased, and over several years, there has been a significant increase in support for global funds. Overall, the number of multilateral partners has grown, coupled with an increase in earmarked and fragmented funding to, in particular, the UN. New multilateral mechanisms are being added to an already complex structure, without the old ones being discontinued. In 2021, 56 % of Norwegian aid through multilateral organisations was earmarked funding.

Support distributed to some UN organisations is highly fragmented, with up to 100 agreements with the same organisation. In the OECD’s review of Norwegian aid, Norway’s choice of channels is highlighted as an area for improvement, noting that the main consideration should be the needs of partner countries, not the priorities of donor countries.71 In addition, this practice may undermine Norway’s efforts to strengthen the multilateral system, as earmarking and fragmentation reduces the efficacy of the multilateral system. This was also reiterated by various actors in the UN system with whom the expert group met during the review period.

Civil society has always been an important channel for Norwegian aid and has for a number of years remained stable at more than 20 % of ODA. In contrast, only 1 % of Norwegian aid is channelled directly through the private sector. However, Norfund invested NOK 5.3 billion in 2021 and with that, mobilised NOK 1.4 billion in private financing.72

Figur 3.8 The ten largest recipient countries, 2017–2021

Note: The ten largest recipient countries of earmarked Norwegian aid to individual countries in the period 2017–2021.

Source: Norad n.d. Norwegian aid results. Statistics and results of Norwegian development aid. Available at https://resultater.norad.no/no.

3.4 Goal displacement and the pressure on aid

For several years, we have seen new goals and thematic priorities being added without established ones being discontinued or deprioritised. This reflects an international trend, where limited ODA resources are being used to address a series of new problems. The OECD DAC summarises it as follows:

- Official development assistance (ODA) cannot solve all development challenges. […] Competing demands – from financing for global public goods and adaptation to the climate crisis to unprecedented urgent humanitarian needs – are stretching ODA budgets to breaking point. It’s hard to deliver effective development when resources are spread too thin. (OECD 2023a p. 7).

This is reflected, among other things, in the fact that aid has become more thematically fragmented, even though there has been a reduction in the number of projects and partners. In 2021, Norwegian aid was distributed among 1,640 projects, 101 beneficiary countries and 869 different agreement partners.73

Boks 3.2 Aid to middle-income countries and emerging economies

In much of Norwegian aid, the development purpose is clearly defined and easy to identify. However, upon closer examination of aid to middle-income countries, it is more difficult to identify clearly defined developmental goals. One such example is the cooperation on forest conservation with Brazil. Another example is Colombia, the biggest recipient of long-term development aid from Norway in 2021, where almost half of the support went to energy and the environment sectors. The most striking example is perhaps the NOK 76 million of earmarked aid that went to China in 2021. Most of this aid, NOK 56 million, went to climate and environmental initiatives, which has been the most important sector for aid to China in recent years by far. China is perhaps one of the recipients of Norwegian aid where the paradox of using the label ‘aid’ for the cooperation – and financing it under the aid budget – is most evident: Extreme poverty in China has virtually been eradicated and the country is an economic major power on the verge of becoming a high-income country.

Norwegian development cooperation with middle-income countries can also have a poverty-reducing effect, of course, but there is nonetheless evidence to suggest that it is of a different nature than that in the poorest countries: Climate and environmental initiatives constitute a large proportion of aid to countries such as Colombia, Indonesia, Brazil, Gabon, Peru, Pakistan, China, and India. In these countries, Norwegian aid is invested in sustainable development, and poverty reduction is to a lesser degree a primary purpose of the cooperation. We saw earlier in the chapter that several of these countries are significant donors, and (collectively) this indicates that the time is ripe to re-think key elements of development aid.

Part of the definition of aid is that it should be directed towards the economic welfare and development of developing countries. A large proportion of Norwegian climate aid – such as cooperation with vulnerable developing countries on climate adaptation or concessional investments in clean energy in countries with poor access to energy – are directed towards this goal. At the same time, climate funding reveals how dilemmas linked to poverty orientation and other considerations related to sustainability are being brought to the forefront. The commitment made by wealthy countries at COP 15 in 2009, to mobilise USD 100 billion annually for emission reductions and adaptation, has not been honoured. In the negotiations on the goal of USD 100 billion, it was decided that the climate funding should be ‘new and additional’, but there is no agreed definition of how that should be interpreted. Countries have different perceptions of what new funds means, and many developing countries have criticised wealthy countries for allocating climate funding at the expense of existing ODA, and not thus as an addition.74 In its reports on climate funding to the UN Climate Convention, Norway (and other countries) justify how these funds can be described as additional. In Norway’s case, it is argued that the monetary amount of climate funding comes on top of the UN target of 0.7 % of GNI.75

Norwegian and international climate funding is generally still in the form of ODA and is only to a limited degree ‘new money’. At the same time, the proportion of aid allocated to climate measures is increasing. One of the challenges this entails can be illustrated by investments in clean energy in developing countries. These are initiatives that can be reported as climate funding and ODA since energy production and consumption are strongly linked to economic development, while they also support a ‘green’ development trajectory. However, it is not certain that all energy projects have exclusively positive effects on social and economic welfare, and there will always be an opportunity cost when spending limited aid funds on clean energy.76 For example, support for access to clean energy in a low income countries has a greater impact on welfare than support for clean energy as a replacement for already existing fossil energy in a middle-income country. The former is more of a contribution to development and poverty reduction, whereas the latter is primarily targeted at emissions reduction. Donors’ climate commitments will likely continue to lead to a distortion of funding towards middle-income countries, where the effect on emission reductions is assumed to be higher but where the need for external concessional funding is lower.

In 2022, the international community adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which highlights the importance of having an ambitious resource mobilisation strategy to support the implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). A target of USD 200 billion per year by 2030, mobilised from all sources, was set for biodiversity measures. This includes increasing international financial flows from developed to developing countries, and in particular the LDCs, to at least USD 20 billion per year by 2025, and to at least USD 30 billion per year by 2030.77 Many of the biodiversity measures will be essential to the welfare of developing countries, now and in the future. According to the World Bank, a collapse of ecosystem services (such as pollination and food from the sea) would result in a significant decline in global GDP, with the greatest impact in the most vulnerable low- and middle-income countries.78 Here, too, however, we see a tension between addressing short- and medium-term developmental goals, and long term global sustainability goals.

Health represents another area where the distinction between funding for development purposes and funding for global public goods are blurred. Funding for global health organisations and research into vaccines to tackle pandemics that affect both rich and poor countries may be hugely beneficial to the latter, but it is not necessarily ODA in terms of its primary objective. That is: Improved public health control and vaccination to prevent pandemics are of benefit to citizens in developing countries, but if the primary objective was health in developing countries, it is far from clear that it is the most effective measure.

Whether it concerns pandemic preparedness, environmental initiatives, oceans, migration, nature or climate, we are increasingly faced with the discussion of whether efforts are motivated primarily by poverty reduction or by something that is also – or perhaps primarily – motivated by self-interests of rich countries. When it comes to peace and security, the ODA directives are clearer than in other areas with global relevance. When the OECD DAC reached a consensus on allowing more military-related assistance to be reported as aid, Norway also wanted to make support for nuclear disarmament possible to report as ODA. However, this was rejected as it constitutes financing for a global public good.On the other hand, the DAC has accepted refugee costs in donor countries as ODA, even though this cannot be described as social and economic development in developing countries. On the contrary, it results in reduced access to funding for development purposes in poor countries and harms the integrity of ODA.

This applies not only to specific topics but also to countries and organisations. Through the development in of a ‘multidimensional vulnerability index’ (MVI), the UN surveys new types of vulnerabilities for various categories of countries. Some countries are more exposed to the consequences of the climate crisis than others, and interestingly, these include low, middle and high-income countries, as it is largely a country’s natural conditions that make them vulnerable.79 Discussions about where the boundaries should be set are ongoing, and there is continuous pressure to include ever new challenges in the international ODA framework.

As seen above, an increasing proportion of Norwegian aid goes to funding initiatives that have multiple goals, including support for global public goods. This does not necessarily mean that the initiatives are outside the scope of the ODA rules, as the DAC rules allows for support of development initiatives that partly or indirectly contribute to global public goods. However, it gives a clear indication that support for global public goods is an important part of current Norwegian development policy.

What is clear is that new objectives and priorities have been included in the Norwegian aid budget without new resources being added. The flexibility of ODA rules, combined with the fact that many OECD countries operate with broadly agreed upon targets of aid as a percentage of GNI, means that there is a political incentive to use ODA-approved funding to finance political priorities that are not necessarily primarily linked to ODA´s primary goal of increased welfare in low- and middle-income countries. Had Norway – and other donors – followed OECD-DAC´s recommendations to, for example, anchor development aid in local ownership and development plans, the approach to, and distribution of, aid would likely be quite different.

We have shown that an increasing proportion of international aid has been allocated to initiatives that support global public goods, that new goals have been added to the development agenda without new funding, and that the flexibility of ODA rules are used to finance priorities that are not first and foremost linked to development and poverty reduction. Members of the OECD DAC have chosen not to address this by altering the definition of ODA to include support for global public goods. Instead, a reinterpretation of the ODA directives has evolved and been partly endorsed, in which the funding of global public goods that is also considered to include the goal of development in ODA-approved countries, can be reported as ODA. Partly because of this, there is currently no clear distinction between ODA and financing of global public goods. This blurred distinction means that there is constant discussion in the OECD DAC about the limits of ODA, and that ODA is being challenged as a measure for rich countries’ contribution to developing countries.

The DAC has been criticised for how the ODA concept is maintained. Key donor countries criticise ODA for being old-fashioned and conservative and neither reflecting global challenges nor ‘new’ financing mechanisms that contribute to development. Some therefore argue that the ODA concept should be expanded. On the other hand, stakeholders from civil society, academia and developing countries criticise the DAC for undermining the integrity of ODA as a measure for wealthy countries’ contributions to developing countries, since too much is included in ODA such as funding for global public goods and in-donor costs.

Boks 3.3 Norway makes full use of the ambiguities in ODA

The Norwegian aid budget is influenced by discussions and consensus in the DAC on distinctions in ODA practices and mandates. Norway has not actively worked in the DAC to expand the definition of ODA but is taking full advantage of the flexibility in the existing rules. Where some donor countries have refrained from reporting on initiatives that are at the outer limits of the rules, Norway reports on all development initiatives that can possibly be interpreted as ODA.

There are examples of initiatives in the Norwegian aid budget that have stretched – and even crossed – the boundary of what may be reported as ODA. Examples of this include environmental and climate initiatives whose main objective is to clean-up oceans or reduce emissions, and where the goals of ‘economic development and welfare’ are not explicit or primary. Other examples are regional initiatives that are reported as ODA in which the geographical focus mainly includes countries that are on the DAC’s list but may also include a country that is no longer on the list of recipient countries. Other sectors in which the limits of ODA are thought to have curtailed the scope of initiatives supported by the Norwegian aid budget are work on global standards, for example against the death penalty, nuclear disarmament, and defence cooperation. In other areas, such as emergency relief and global health, the Government has chosen to use exemptions from the ODA rules in its aid budget. In its proposed budget for 2022 (Proposition No 1 to the Storting 2022), the Government emphasised that humanitarian crises could affect vulnerable people living in high-income countries, and that the Government will consider contributing humanitarian aid, even though these are not countries approved to receive ODA.

In its annual Development Cooperation Report, the OECD has repeatedly pointed out that the financing of global public goods is, and will remain, a major challenge for aid. The 2023 report emphasises that the point has been reached where it is necessary to find alternatives to ODA for funding health security and other global public goods, in order to avoid deprioritising development and growth in poor countries.

3.4.1 Total Official Support for Sustainable Development (TOSSD)

TOSSD is an international framework for a broad spectrum of officially supported financial flows to promote sustainable development. This is a relatively new framework for international financing, which originated from the Conference on Financing for Development in Addis Ababa in 2015. TOSSD monitors official support and mobilised private financial flows to sustainable development in developing countries and to international public goods, at the global and regional level. The main criterion for an activity or initiative to be reported as part of TOSSD is that it directly contributes to one of the SDG targets and if no substantial detrimental effect is anticipated on one or more of the other targets. TOSSD makes a distinction between ‘direct’ support for low- and middle-income countries and support for what it calls international public goods. This distinction arises from the fact that funding related to the first category (transfers to poor countries) is referred to as ‘Pillar I’, while efforts for cross-border public goods are referred to as ‘Pillar II’. In both cases, funding must be in line with the main criterion for supporting the SDGs. Furthermore, Pillar II activities must provide ‘substantial benefit’ to TOSSD countries and/or be carried out in direct cooperation with those countries or private and public institutions from those countries (see definitions and concepts in Appendix Z).80

TOSSD has been developed and maintained by the TOSSD Task Force, but the long-term ambition is to bring TOSSD under the auspices of the UN to ensure representativeness. In March 2022, the United Nations Statistical Commission approved a new SDG indicator 17.3.1 for ‘Additional financial resources mobilised for developing countries from multiple sources’. The OECD and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) are co-administrators of the SDG indicator, and TOSSD is an official data source for the global indicator framework for the SDGs.81

The ambition for TOSSD is that it becomes and delivers some of the things ODA cannot:

- An inclusive framework, with membership representing all regions of the world, and a formalised governance structure representing a balance between income categories.82

- Overview of South-South cooperation and other efforts for development from ‘new donors’.

- Overview of funding for global public goods for the benefit of developing countries over and above ODA.

- The opportunity to gain an overview of international investments in sustainability, which can be useful in efforts to coordinate and collate global sustainability efforts.

3.5 Development cooperation: Ripe for modernisation

Available policy instruments and sources of funding are not keeping pace with the scale and complexity of challenges. The money does not stretch far enough and – just as worrisome – the tendency to stretch aid funding to meet new needs or goals undermines the effectiveness and credibility of development cooperation. This trend is also reflected at an institutional level. The mandates of various multilateral development institutions are broadened without a corresponding increase of funding. In addition, there is little cooperation and coordination required to address complex problems related to violent conflict, humanitarian crises, and climate change. UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed has pointed out, for example, that ‘Our current system of development co-operation is simply not meeting the scale of this challenge’.83The expert group’s meetings with representatives of UN organisations and the World Bank revealed serious concerns, indicating that the system for development cooperation is dysfunctional in a number of areas, not least because of the propensity of donor countries to earmark contributions and use multi-donor trust funds. While earmarking may give donors visibility and control, it undermines the strength and capacity of multilateral cooperation when it comes to development purposes.

This crisis of governance is partly due to the fact that most development policy instruments, financing flows and institutions were established to deal with a more limited set of problems, and not the type of global and overlapping crises we are witnessing today. Although a focus on prevention has been on the agenda for a long time, the Covid-19 pandemic and the consequences of climate change have made us more aware of the significance of preparedness and prevention. The inadequate provision of global public goods – pandemic preparedness, conflict prevention, climate measures and nature conservation – can have catastrophic consequences, yet these challenges are still not prioritised highly enough. The result of this is a global ‘tragedy of the commons’, despite clear knowledge of the consequences of a lack of investment in prevention and preparedness. What is needed is binding international cooperation in which nations contribute according to their ability.

There is currently increased attention to the imbalance of power between the Global North and South. Emerging economies have become important development stakeholders and have a greater influence in decisions taken within the architecture of global governance, but more developing countries demand a more prominent role in discussions about the funding of development and global public goods. This is a follow-up point in the OECD’s flagship report Development Cooperation Report 2023 which addresses the ongoing discussion about the decolonisation of aid and points to the need to build meaningful partnerships and to draw on more research from low- and middle-income countries. It also states that DAC members should define clearer goals for locally led development, use and support local stakeholders to a greater extent, and adjust development cooperation in accordance with the partner country’s own priorities.84 This localisation debate is an effort to include and ensure sufficient resources for local authorities. Increased inclusion is also one of several measures mentioned inthe High-Level Advisory Board on Effective Multilateralism’s report published in April 2023.85 A shift that would allow countries to determine their own development trajectory is crucial for sustainable development at the overarching level.

The DAC has been increasingly challenged as a donor forum. The committee, which represents the world’s largest group of traditional aid providers, has lost some of its prominence as a donor forum due to the emergence of new major economies (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – BRICS) and other aid donors. Although the DAC has implemented a number of reforms and become more inclusive, it is still criticised for being an exclusive ‘donor club’ that makes decisions that affects the entire development cooperation, yet without including the developing countries affected by these decisions.86

Developing countries, and particularly civil society organisations, have called attention to this asymmetry, and the DAC – to its credit – have acknowledged it. The UN Secretary-General and the OECD are both now talking about a new type of ‘social contract’ adapted to current challenges.87 Such an approach involves more binding and mutual cooperation across countries to achieve a sustainable future. The OECD DAC stresses that this ‘is about much more than ODA’.88 What is needed is a comprehensive approach that draws on all policy instruments, sources of funding, and policy areas. There are many ongoing international initiatives aiming to improve the system and secure more funding, including under the auspices of the UN, the World Bank, and the IMF, in addition to key donors such as Germany and France. These initiatives indicate that there is a window of opportunity to influence international processes with the aim of making international development cooperation ‘fit for purpose.’

3.6 Is aid a good investment?

Aid is, under certain conditions, a good investment. It will, however, in many cases be difficult to document the effect of aid and conclude with certainty that an initiative or programme has had a causal effect on a particular outcome. Given the limitations of this report and the extensive international research on how, under what conditions, and in which contexts aid makes a difference, we are only able to point to some overall characteristics. Three major research traditions can be identified that substantiate in different ways that aid can be, and often is, a good investment.

Throughout the 1990s, what subsequently became known as the ‘evidence revolution’ became a widespread concept in economics and, to varying degrees, in the other social sciences. In research on aid, there was a particular increase in the use of randomised control trials (RCTs). We have learned from this literature that it is entirely possible to design aid measures that cost-effectively deliver results across different themes, and that it is possible to achieve such results even in contexts in which it is otherwise difficult to work.89 A commonly used example is cash transfers and social safety nets. Cash transfers are shown to be an effective way of reducing poverty, increasing food security and improving health and education in a wide range of contexts.90 Controlled studies show that cash transfers are an exceptionally effective aid measure and an excellent investment in sustainable development. Cash transfer of sufficient size will also have an effect in the longer term.91

Boks 3.4 Reduction in maternal and neonatal mortality

Maternal and neonatal mortality are a huge cost to society. In 2019, there was an estimated welfare loss of USD 462 billion in the 55 countries with the highest rates of maternal and neonatal mortality, representing almost 6 % of the countries’ GDP. A report recently published by the Copenhagen Consensus Center shows that increased coverage of Basic Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (BEmONC) from 68 % to 90 %, and better access to family planning, are the most cost-effective ways to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality in these countries. For every USD invested, the social and economic benefits are estimated to be USD 87, and the cost-benefit ratio is thus 87.

On a more aggregated level, large overview studies show correlations between human development and aid, making it likely that aid has contributed to this development. Charles Kenny and Zach Gehan document that in a historical context, developing countries have seen impressive development along many of the most important measures of human development.92 Among other things, poor countries are experiencing higher living standards, longer life expectancy, higher levels of education and lower infant mortality rates than Western countries experienced when they were at a similar level of socio-economic development. These are precisely the areas in which aid had a particular focus and where it can likely be shown that aid at times had a significant impact.

There is also a broader international discussion related to the effect of aid on economic growth. Contributing to economic growth at a national level has never been a specific goal for Norwegian aid but unsurprisingly, it is considered the most overarching goal that aid can achieve. It is of course difficult to study the impact aid has on economic growth. It is by no means random which countries receive aid, and it is extremely complicated to separate the effect of aid from other factors. An early influential study showed that aid can have a positive effect on economic growth, but only when the recipient country implements what was classified as good policy.93 Following this, several conflicting studies were published showing that aid had a negative, positive or no effect on growth. A 2012 study endeavoured to clarify this discussion and found, given a set of assumptions about when the impact of aid will be visible in economic growth, that aid has in general contributed to economic growth over time.94 Recent meta studies and studies that more directly try to account for the fact that aid allocation is not random also indicate the likelihood of aid, over time, making an aggregate contribution.95

There are promising models for more meticulous assessments of what works and what is effective based on ‘benchmarking’ and ‘best in class’ approaches, which appear to be favourable methodologies for evaluating various forms of aid (see box 3.5).

Boks 3.5 Promising methods: ‘Benchmarking’, ‘best in class’ and scoring

A decidedly comprehensive approach to development has often prevented more widespread use of benchmarks, which are a standard against which to judge if assistance is well spent. The use of benchmarks is an issue that is increasingly being raised (including by major donors such as USAID), particularly in light of research on cash transfers showing that the methodology has an effect on far more goals than just poverty reduction. However, it is difficult to specify one standard against which all efforts towards achieving the SDGs can be measured, even though there are individual initiatives and interventions, such as cash transfers, which appear to have positive effects across goals in the short and medium term. The complexity of the sustainability agenda suggests that we should instead adopt a ‘best in class’ approach to effectiveness.

When it comes to information about past results, we currently have little in the way of systematic approaches, quality assurance or comparisons. This does not only apply to Norway. There is no international database of readily available information about the evaluation of effects, costs and results of a myriad of initiatives in international development. One feasible way of improving the overview and the ability to learn is the use of scoring. An immediate summary of the assessment can be obtained by setting a score for each assessment of each aid initiative.

It is often a matter of finding one or more common denominators in the form of properties or characteristics of the results that make them easier to compare. It is crucial that the assessment is available in order to understand why the score has been given. The score is necessary for aggregation purposes and provides a quick overview and an indication of progress for an entire portfolio. It corresponds to the requirement in the Regulations on Financial Management in the Central Government on the possibility of assessing the degree of goal attainment. A number of objections may be raised, but the methodology provides clearer guidelines, frameworks and a systematic approach to assessments that are in any case based on the discretionary judgement of the executive officer. An appropriate methodology is already available but has not been sufficiently taken into use (between 2019 and 2021, an assessment of results and scoring only exist for 151 projects out of 4,104 aid agreements). A plethora of different countries and contexts also adds to the difficulty of ascertaining a benchmark or ‘universal score’. One option would be to take a selection of SDGs and their indicators and consider these in light of each country’s progress. This would, at the very least, measure a country’s progress against its own benchmarks.

3.6.1 What works in the most difficult contexts?

We have already identified fragile states and contexts as a particular challenge. According to a large compilation of evaluations and research from three fragile states that receive Norwegian aid (Afghanistan, South Sudan and Mali), very little of the most ambitious and transformative aid, such as institutional development, capacity-building, governance, justice and the rule of law, etc. has worked effectively.96

Smaller scale, local and ‘technical’ (non-political and non-sensitive) interventions seem to work better. Examples of such projects include increasing access to basic healthcare and education, individual agricultural and water projects that are of great local relevance, and savings and loan groups for women. However, many of these initiatives are not sustainable and must largely be financed by external donors. Certain capacity-building projects can work, but success is often limited to the skills and expertise of individuals (ibid.).

The main conclusion of the literature review is in line with an important finding from an evaluation of Norway’s involvement in South Sudan, namely that transformative goals related to governance and democracy were based on inaccurate assumptions and did not lead to results, but that parallel systems that could serve the population were a realistic alternative.97 However, a large-scale evaluation of Norwegian aid to Somalia found that Norway had engaged in small but risky state-building projects that are unlikely to have been properly established without Norwegian support.98

The emphasis on the legitimacy and capacity of institutions is pervasive in much of the literature, including in the OECD Principles for Good International Engagement in Fragile States and Situations.99 The task has not been made easier by the fact that more and more fragile contexts have illegitimate political governance.100 Approximately half of the population of fragile states live in such contexts, in which ‘normal’ aid for institutional development, ‘good governance’, anti-corruption, security reform and inclusive political processes are extremely difficult.

These are contexts in which it will not be possible to adhere to some of the OECD’s important principles for aid effectiveness and it will be important to work in other ways. Particular emphasis is placed on a continuous adaptation based on updated analyses of the context – what can be described in short as a constant interaction with the context.101 Where it is not possible to work at the government level, there are examples of contexts in which national systems have been ‘shadowed’ (endeavours to align aid with what existed of welfare services, but implemented by external parties).102 In some situations, however, it is necessary to resort to non-governmental organisations and international systems to serve the population.

Various evaluations and literature also highlight willingness to accept risks associated with adaptation and ‘trial and error’, and to focus on relevance, thinking short-term (not seeking perfection and sustainability, but relevance and momentum), small-scale and local initiatives, as well as pragmatic agreements with local and regional coalitions.103 The question is whether the current general administrative checks and procedures in the aid system allow such risk-taking, innovation and pragmatism that effective efforts in such contexts demand. Norway has agreed to accept a higher degree of risk in such contexts despite the tension between the administration’s need to control funding in fragile states and the need for subsidiarity, autonomy and experimentation.104 A more ‘realistic’ approach to reform in fragile contexts may also mean cooperating more with different types of actors and partners, including those with whom aid has not traditionally been associated.105

Boks 3.6 Nexus – a comprehensive approach to fragility

It is important to recall the work on the principles and lessons learned from what are called a ‘comprehensive approach’ – or nexus approaches – in long-lasting and complex crisis situations and conflicts. Important milestones in this work have been the Grand Bargain Humanitarian Summit in 2016 and the OECD DAC Recommendation on the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus from 2019. These initiatives criticise the outdated structure of the current development system in the face of many of today’s most difficult development contexts, making the current responses less effective. ‘Chronic’ crises and ever new layers of overlapping crises (conflict, failing food production, migration, climate change) mean that our model for different phases of development – humanitarian crises, reconstruction and long-term development, peace and reconciliation – does not make as much sense. In practice, the divisions around which we have built the development structure are fluid and dynamic. While the purpose of humanitarian efforts is to save lives and alleviate suffering in line with the humanitarian principles, long-term development policy and stabilisation efforts aim to address the root causes of conflict and vulnerability. The nexus approach is an endeavour to improve the interaction between these efforts and work towards longer-term solutions, improved prevention and institutional resilience to the next crisis, whenever possible. Having more unified goals across the different areas of engagement, as well as better coordination and long-term commitments, will force actors to focus more on the root causes of conflicts and crises and on a sustained reduction of needs.

3.6.2 Effective production of global public goods?

There is reason to believe that the provision of global public goods will continue to distort and reshape aid. ODA is far from being an adequate framework for this, and a wider range of policy interventions are needed. In fact, there is reason to believe that measures and resources from outside the traditional boundaries of aid are more effective at providing the world with global public goods. Moreover, an adequate solution to global challenges must need not always involve more development funding. It may, for example, be brought about by the reorganisation of existing funding, policies and incentive schemes. For example, carbon taxes and quotas are part of the solution to the climate problem. As UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has repeatedly pointed out, the adverse effects of the financial system on climate, nature and human welfare are a fundamental reason for the under-provision of global public goods. That is why a ‘do no harm’ principle for investment and financial activity will be an appropriate first minimum requirement for the efficient provision of global public goods.106

According to Clement et al. expenditure on petroleum subsidies in low- and middle-income countries totalled USD 895 billion.107 This substantial sum is not targeted towards the poorest sections of the population (SDG 1) nor measures to reduce climate change (SDG 13). It also undermines other SDGs, such as good health and quality of life (SDG 3), reducing inequality (SDG 10), sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11) and protecting life on land (SDG 15). Another example is subsidies that cause harm to nature that are allocated to the agriculture, fisheries and forestry sectors totalling about USD 500 billion each year – equivalent to four times the funding for protection of biodiversity.108

Another important perspective is how international crises can be anticipated. Conceicao calculates that adequately producing an important range of global public goods will amount to between 1 and 10 % of the cost of continued under-provision.109 In the case of global public goods and in line with the idea of prevention, it would also be natural to redirect funding towards a ‘better safe than sorry’ principle.

The Sustainable Development Agenda entails an expansion of aid and development policy to also address global ‘spillover effects’ (GDI 2020), which is often discussed in the context of global public goods. A key element here is the agenda for policy coherence for development.110 This means reducing conflicts between economic, social and environmental goals and cultivating synergies between different policy areas with the object of contributing to sustainable development.111 In relation to this, the OECD’s latest peer review of Norway in 2019 stated that ‘Norway demonstrates a commitment to policy coherence for sustainable development but struggles to achieve it in practice.’112 This criticism was repeated in the OECD’s mid-term review in 2022. The OECD has developed eight guiding principles for coherent sustainable development. The principles range from political vision and leadership through long-term plans and commitments to concrete forms of cooperation and reporting. Together, they represent a new standard for interdepartmental cooperation and long-term visions. A real and effective contribution to global public goods should therefore include an analysis based on these principles.

3.7 Conclusion

The discussion above illustrates that the need to mobilise more resources and establish better international mechanisms to deal with a broader set of problems than the aid system – and ODA – can handle. Another dimension to this is time. An absence of sufficient resources to tackle today’s problems will make it substantially more expensive to deal with them in the future. Significantly more resources and a system that can use these resources effectively are needed to avoid any further reversal of economic development in the poorest countries, to prevent the consequences of climate change and to establish a better response to future pandemics. There is room for more efficient use of resources, and the demand for increased resources must therefore be accompanied by an increased demand for effectiveness. Chapter 4 introduces a framework for this, which establishes a number of principles for assessing the effective use of resources, and thus also provides a guiding principle for future development policy, including the role of ODA.