2 Introduction

To deny people their human rights is to challenge their very humanity.

Nelson Mandela

Although Norway’s legal responsibility is limited to people within its jurisdiction, Norway has a long tradition of involvement in efforts to protect the human rights of individuals in other countries, with the overall aim of strengthening international human rights protection. Norway’s own experience of democracy and the rule of law, and of a welfare state that respects and protects personal freedom, provides a solid basis for the Government’s efforts in this area.

The Government’s international human rights work reflects a policy based on interests and engagement, in which human rights protection is both a fundamental aim in itself and a means of achieving other objectives. Respect for human rights is a cornerstone of democracy, just as real democracy is a prerequisite for the realisation of human rights. Countries that respect human rights are more stable and predictable than those that do not. The protection and promotion of human rights thus plays a part in creating a safer and more open world, which is also in Norway’s interests.

A commitment to human rights, democracy and the principles of the rule of law must lie at the heart of Norway’s foreign and development policy. Respect for human rights and international law, together with binding international cooperation, are key to pursuing a responsible foreign policy, and Norway’s record in these areas enhances its credibility when it seeks to promote Norwegian interests. For this reason, the Government announced early on that it would present a white paper to the Storting highlighting the increased emphasis on human rights in our foreign and development policy.

During the course of the 15 years since a white paper on human rights was last presented to the Storting, the world has changed, and the international community is facing increasingly complex challenges with far-reaching implications for human rights. In autumn 2014, there are more refugees in the world than at any time since the Second World War. At the same time, the international community is having to respond to several humanitarian crises in parallel, categorised by the UN as level three emergencies, the UN’s highest level of humanitarian emergency. Poverty, conflict, terrorism, epidemics, climate change and environmental problems continue to have major consequences for human rights. The tension between secular and religious centres of power and between different religions poses further challenges. Digital advances have also created new, serious threats from both state and non-state actors. Instruments that are used to combat terrorism and to safeguard the security of citizens can at the same time pose challenges in terms of protection of privacy and freedom of expression. This applies for example to mass surveillance and data collection. Furthermore, there is a clear correlation between the human rights situation in a country and the desire of its citizens to move or flee, and possibly seek asylum in another country. This illustrates the close links between different policy areas.

At the same time, awareness of human rights has grown all over the world. The internet and social media have dramatically changed the way people communicate and have made it more difficult to conceal human rights violations from the rest of the world. Technology has created new and better opportunities for the free exchange of information and views, and has enabled broader political participation and the development of better organised opposition movements. Today, the actions of states are scrutinised more thoroughly than ever before, and civil society is playing an ever more important role in pushing for legal and political reforms by protesting against marginalisation and oppression. Popular uprisings and calls for democracy and public participation have recently brought about the fall of a number of authoritarian regimes.

At the national level, the work of an increasing number of civil society organisations and human rights defenders has significantly improved the human rights situation in many countries, as has the establishment of independent national human rights institutions. The adoption of legislation that places restrictions on the flow of information, on freedom of expression, on freedom of assembly and association and that leads to a shrinking of democratic space is therefore very worrying. Peaceful protests are being suppressed and censorship and political control of the media are widespread. In some instances, there is clear disregard for the right to life and the prohibition against torture. Many countries refer to security and counter-terrorism considerations to justify strict state control and mass surveillance. Human rights defenders and journalists have become the target of threats, harassment and arbitrary arrest, and in some cases forced disappearances and even killings are being carried out in order to silence their voices. In many countries, minorities and members of the political opposition are persecuted and attempts are made to control groups that challenge the central authorities, often through the adoption of legislation.

A changing world

The world has entered a period of geopolitical change. Economic growth in certain regions is causing a significant shift in global power. Economic and political influence is moving towards the south and the east. The financial crisis has reinforced this trend. This shift in global power shows that there is a connection between economic growth and political influence. The Government needs to strengthen contacts with new partners while maintaining old ties if it is to be able to pursue a viable foreign policy that promotes a world order based on the rule of law. We cannot simply assume that all the emerging economies have developed a tradition for safeguarding human rights. Nor can we assume that other countries base their policies on the same fundamental values and aims as those that underpin the international human rights conventions. Many states do not respect the universality of human rights, or rely on a restrictive interpretation of human rights. Many states seek to undermine rights that they have undertaken to respect under international law. This can be clearly seen in the UN and other multilateral forums, where alliances of states cite traditional values and use religious dogma to restrict the rights of individuals, and refer to principles of national sovereignty and non-interference in the internal affairs of states. In such cases the Government will make it clear that human rights are universal and indivisible, and that individual states cannot opt out of their human rights obligations by referring to what they claim are national traditions or values.

Textbox 2.1 Militant jihadist groups

The international human rights conventions place obligations on states and grant rights and freedoms to individuals. However, in situations where states no longer have real control over parts of their territory, for example in cases of internal armed conflict or in areas where terrorism is widespread, the implementation of human rights obligations is undermined. States may find that they are no longer able to safeguard the rights of their citizens.

Militant jihadist groups such as ISIL, Al-Qaeda and Boko Haram are responsible for massive and grotesque attacks on the civilian population, massacres of whole villages, widespread kidnapping, torture, and sexual assault, particularly against women and young girls. In some cases, people are being forced to give up their own religion and convert to the faith of the terrorist groups. ISIL is a particularly frightening example of a group that, by means of extreme violence, is acquiring economic resources, taking control over large areas of land, terrorising entire population groups and threatening the existence of states. ISIL is operating across national borders, is well organised and has ambitions to make further territorial gains. The group thus represents a threat to life and security beyond the region in which it is operating. ISIL’s actions can only be regarded as serious criminal acts and may qualify as crimes against humanity.

The Government’s efforts to strengthen Iraq’s ability to combat these groups, where these are operating on Iraqi territory, will help indirectly to enhance Iraq’s ability to safeguard the human rights of its citizens, and will also help to ensure that members of terrorist groups such as ISIL are held accountable for their crimes. In this way, these efforts are part of our work to safeguard and strengthen the protection of human rights at the international level.

Systematic use of instruments and the importance of broad alliances

This white paper sets out what the Government will do to strengthen the human rights dimension in Norway’s foreign and development policy. It focuses in particular on enhancing coordination, increasing effectiveness and ensuring a more systematic use of the various instruments that are available. Where the Government sees negative developments or human rights being violated, it will express its concerns. The Government will convey its criticisms and concerns directly, at senior official level and at political level. When appropriate, Norway will express its concerns openly, for example in the form of public statements. Support for civil society’s human rights activities, combined with a focus on the inadequacies of the efforts of national authorities, can often lead to positive change over time.

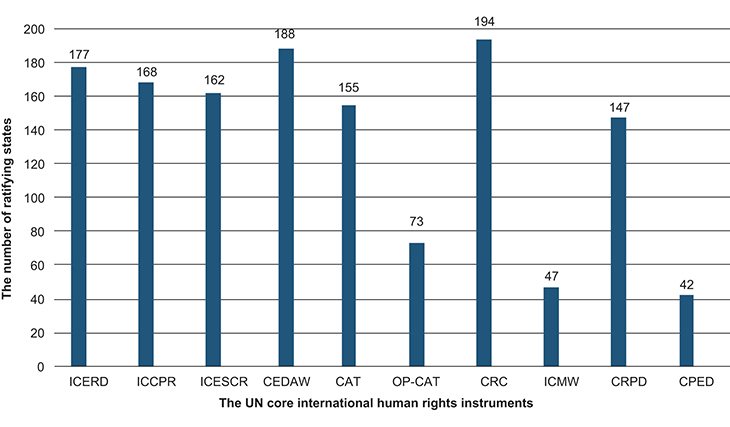

Textbox 2.2 The UN core international human rights instruments

There are ten core international human rights instruments, some of which are supplemented by optional protocols that deal with specific topics. The ten core instruments are:

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1965) – ICERD

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) – ICCPR

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966) – ICESCR

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979) – CEDAW

Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984) – CAT

Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (2002) – OPCAT

Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) – CRC

International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (1990) – ICMW

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) – CRPD

International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (2006) – CPED

Figure 2.1 The diagram shows the number of states that have ratified the UN core international human rights instruments.

Norway’s efforts to promote human rights will be most effective if we further develop cross-regional alliances, both with other states and with civil society. In this work, the Government can benefit from Norway’s clear international profile in the field of human rights. The Norwegian authorities take a broad approach and are involved in most of the human rights issues on the international agenda. The Government will support the independent media and strengthen partnerships with civil society, the academic community, the business sector, and religious groups and cultural networks, which can all help to disseminate knowledge about human rights beyond traditional arenas. The Government’s approach is based on recognition of the fact that a long-term perspective is needed in this area, and that all countries face different challenges that vary in nature and scope. This is reflected in international cooperation on human rights, including in the UN and Council of Europe monitoring bodies and in the UN Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review process, which allows all countries to raise human rights issues in other countries and to put forward recommendations. Following Norway’s Universal Periodic Review in April 2014, the Government approved a number of recommendations, which it is now following up.

Development of the white paper

In developing this white paper, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has considered it important to ensure a broad and inclusive process. Meetings have been held with other parts of the public administration, the business sector, civil society organisations and other relevant actors, all of whom have provided written input. The intention behind this approach was to make the white paper relevant and feasible, and to encourage involvement and inspire ownership as regards the implementation of its recommendations.

Textbox 2.3 International human rights protection

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that ‘all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights’. Since its adoption in 1948, the UN has introduced a number of conventions and declarations relating to the protection of human rights, and today the world has a well-developed set of international norms that states in all regions have endorsed. A treaty body (a committee of independent experts) has been established for each of the UN’s ten core instruments to monitor implementation of the treaty provisions by its states parties.

Promoting human rights is a key task of both the UN General Assembly and the UN Security Council. The Human Rights Council, the UN’s main human rights body, is mandated to address both thematic issues and situations in individual countries. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) plays an important role as an independent voice in the area of human rights protection and promotion, and acts as secretariat for the Human Rights Council and the treaty bodies. OHCHR provides guidance and technical support to individual countries to assist them in implementing their human rights obligations.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a specialised agency of the UN and is responsible for developing, monitoring and enforcing international labour standards. The ILO has developed a comprehensive set of legal instruments, and it is common to refer to the ILO’s eight core conventions as human rights conventions. These core conventions relate to issues such as freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining, the abolition of child labour, the elimination of forced or compulsory labour and discrimination.

Regional organisations can also play an important role in promoting the international protection of human rights, by developing norms and effective monitoring mechanisms. In Europe, the European Court of Human Rights issues legally binding judgments and decisions on states’ compliance with the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The Council of Europe has also developed a number of special conventions with separate monitoring mechanisms, such as those relating to minorities, human trafficking, torture, domestic violence, and economic and social rights. The Council of Europe has a separate Commissioner for Human Rights. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) complements the work of the Council of Europe in the field of human rights. The OSCE’s three independent institutions — the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, the High Commissioner on National Minorities and the Representative on Freedom of the Media – work, together with the OSCE’s various missions, to build institutions, strengthen democratic structures and promote the participation of civil society in conflict-affected countries and regions.

In other parts of the world, the Organization of American States (OAS), the African Union (AU) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in particular have adopted instruments and begun developing mechanisms to protect human rights in their respective regions.

The development of international courts to ensure that perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes are brought to justice is also an important contribution to the work of increasing compliance with human rights obligations. The International Criminal Court (ICC) plays a key role in these efforts.

Limitations of the white paper

The white paper does not cover the work being done to promote human rights in Norway. Nor does it discuss Norway’s role as a financial investor, through the two parts of the Government Pension Fund, the Government Pension Fund Norway and the Government Pension Fund Global, which are managed by Folketrygdfondet and Norges Bank, respectively. The Ministry of Finance presents a white paper to the Storting annually on the management of the Government Pension Fund, the most recent being Meld. St. 19 (2013–2014). These white papers describe the Fund’s work to ensure sound and responsible management, and it is therefore natural for all matters relating to the management of the Fund to be considered by the Storting when the annual white papers are presented.

Financial and administrative consequences

No administrative changes to the Ministry’s or subordinate agencies’ areas of responsibility are envisaged as a result of this white paper. All measures discussed in the white paper will be funded within the existing budgetary frameworks of the ministries concerned.