7 Efforts to promote human rights in individual countries

The overall goal of the Government’s international human rights work is a lasting improvement of the human rights situation in all countries. This will require local ownership and responsibility. Bilateral dialogue on human rights is therefore to be an integral part of our broader bilateral relations at both senior official and political level.

Norwegian authorities will take a consistent approach to cooperation and support for human rights in every country. Norway will have a principled and clearly recognisable profile and will take a long-term approach, ensuring sufficient flexibility. Norwegian authorities will make it clear that the importance of respecting human rights is promoted in all countries. The Government will have a particular engagement in countries that are large aid recipients, in countries where there are serious violations of human rights, in countries with a significant Norwegian business activity, and in fragile states.

International human rights law is the point of departure for work on the bilateral level. This is based on the human rights commitments and obligations states are bound by and that they have undertaken by becoming parties to human rights instruments. Norway will make it clear that it is promoting universal human rights, and do not represent the special views of any particular country or small group of countries. Some of the most important guidelines for our long-term efforts are the convention texts, reports and recommendations from the treaty bodies, global and regional special procedures, and the UN Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review.

Many different actors are involved in international follow-up of how individual countries are fulfilling their human rights obligations, including states, intergovernmental organisations and civil society organisations. Coordination is therefore important in order to ensure the best possible international approach and division of roles.

The Government intends to make more systematic use of the various foreign and development policy instruments it has at its disposal in its human rights work. This will require a clearly-defined approach based on regular analyses and reference points. Moreover, it is becoming increasingly important to consider bilateral and multilateral efforts in conjunction with each other. Knowledge and experience gained from bilateral work will be utilised in multilateral work, and vice versa. This makes it possible to achieve positive synergies with a view to a mutual strengthening of our efforts to promote human rights.

7.1 Systematic approach

Promoting human rights at the country level is a key part of the international human rights work. The most important step in our bilateral level work is to strengthen the methodology followed by the Foreign Service and make it more systematic.

Textbox 7.1 Different or conflicting views on human rights

There are many challenges that need to be overcome in human rights work. Often, the greatest obstacle is a lack of resources or the political priorities of countries where Norwegian authorities are engaged. In other cases, there may be opposition from other countries or from international interest groups that are involved in bilateral work. This applies particularly to efforts to help religious minorities and in issues relating to sexual orientation and gender identity. The Norwegian authorities intend to focus more attention on activities and actors that undermine respect for the universal nature of human rights, in other words deny that they apply to all people everywhere. An open and critical approach of this kind is essential for achieving more with the funding available for international human rights work.

Norway’s systematic approach takes the universal human rights as its starting point, and has five main elements: understanding the human rights situation in the country; overall country specific knowledge; an understanding of Norway’s latitude to act; the choice of instruments and tools; and evaluation.

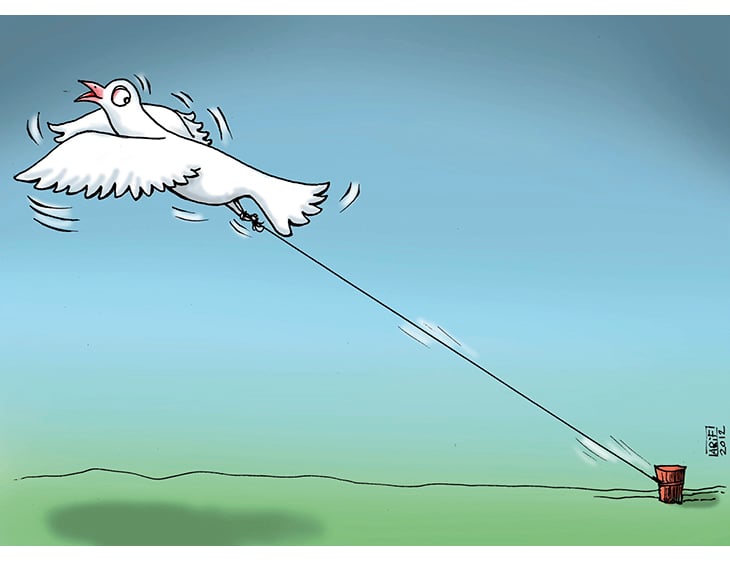

Figure 7.1 Arifur Rahman, Bangladesh Rahman is a cartoonist who was jailed and persecuted in his own country because of accusations that one of his drawings ‘hurt religious sentiments’. He has since moved to Norway with the help of the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN). ICORN helps persecuted journalists and writers to find a temporary home and financial support.

7.1.1 The human rights situation in the country

Effective work at country level begins with a sound, up-to-date understanding of the human rights situation in a particular country. This understanding will be based on information from the Universal Periodic Review process and other relevant UN bodies, decisions by regional monitoring mechanisms, as well as reports from media and freedom of expression- and civil society organisations. In addition, Norway’s missions abroad gain insight through dialogue and exchange of assessments with local actors. The involvement of various Norwegian actors in this work also produces valuable information. All these sources combined give a good basis for an overall analysis. In this regard, it is particularly important for Norwegian personnel to have a thorough understanding of the thematic priorities described in Chapter 3.

Greater analytical capacity and more knowledge about the human rights situation globally is needed for Norway’s bilateral work. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs will therefore strengthen its in-house tools for producing thorough and regularly updated analyses of the human rights situation in countries where the Norwegian authorities are engaged.

7.1.2 Overall country specific knowledge

Knowledge about the human rights situation must be considered in conjunction with overall country specific knowledge. An understanding of challenges and opportunities in individual countries, such as political and economic trends, demographic factors, the resources available, the role of religion, internal conflicts and regional dynamics, will be of crucial importance for our ability to interpret the human rights situation in a country. Country-specific knowledge also includes information on the actors operating in a particular country, including civil society organisations, international donors and bilateral efforts of other countries. The periodic reports on the human rights situation from the missions therefore need to be supplemented with broader country analyses, as provided in their semi-annual reports.

The Foreign Service and other parts of the public administration need to be able to draw on high-quality knowledge relevant to human rights from external sources. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs therefore cooperates closely with a number of Norwegian and international research groups, for example by commissioning analyses of selected issues or the situation in specific countries.

Textbox 7.2 Cooperation with other actors

Norwegian authorities cooperate with a wide range of actors in promoting human rights bilaterally, for example:

national authorities such as ministries of justice and home affairs, prison services, the education sector as well as parliamentarians;

local civil society actors such as religious and belief groups, cultural institutions and other actors in the cultural sector, media and freedom of expression organisations, lawyers’ and doctors’ associations, the business sector, trade unions, ombudsmen and human rights organisations;

universities, colleges, research institutes, think-tanks and other research and analysis groups;

Norwegian and international civil society and human rights organisations;

multilateral and regional organisations and mechanisms established under their auspices;

embassies and delegations of other countries.

7.1.3 Norway’s latitude to act

The extent to which Norway can play a supporting role will depend partly on the human rights challenges in a country and the situation in the country otherwise. However, an equally important factor may be a sound understanding of Norway’s relations with the country – the authorities, the opposition and civil society – and of whether there are special circumstances indicating that Norway should adjust how it works, for example when Norway has a long-standing presence or particularly good bilateral or personal relations with the country. Norway’s options will also depend on which sectors other actors are working in and on the tools and instruments available for use in the country in question. A good understanding of all these factors will make it possible to use Norwegian resources more effectively. In order to contribute most effectively to human rights work in a country, an overall assessment should always take the following into account:

the quality and breadth of the bilateral cooperation and political dialogue with the country, since these influence the scope for dialogue on human rights and effective messaging;

political, socio-cultural, religious, social and cultural factors and traditions that influence the human rights situation in the country and people’s attitudes to human rights;

the approach to be taken in the human rights work, choosing between bilateral or multilateral channels, and the extent of cooperation with other actors in the country;

the choice of priorities, including finding a balance between long-term efforts and acute situations that require immediate attention;

which instruments and tools it is possible to use;

the choice of cooperation partners: for example local authorities, independent monitoring services, civil society organisations, multilateral organisations, other donors.

7.1.4 Relevant instruments and tools

Identifying instruments and tools to be used in bilateral efforts to promote human rights is a three-stage process. The first is to obtain a good general overview of all instruments and tools available and their potential effects. Secondly, these instruments and tools must be assessed in relation to the human rights situation in the country. The third stage is to select certain instruments and tools on the basis of Norway’s latitude to act.

It can be a challenging task to identify the most effective instruments and tools. It may be easy to eliminate those that may not be relevant in a particular country, but more difficult to identify those that will be most effective. In most cases, it will be appropriate to choose several instruments and tools that can be used in parallel and have overlapping effects.

Instruments and tools are further discussed in Chapter 7.2.

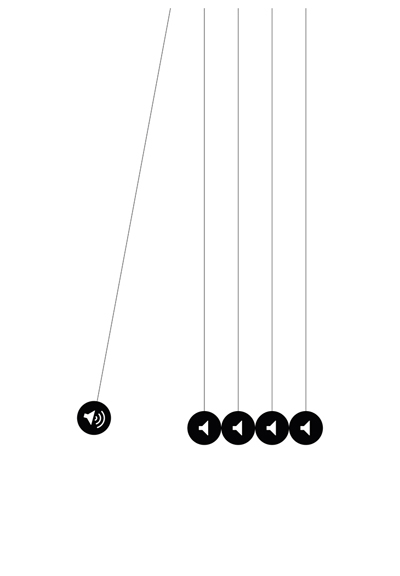

Figure 7.2 Mathieu Daudelin Pilotte, Canada

7.1.5 Evaluation

The framework for human rights work at country level renders continuity and clarity important. The day-to-day tasks tend to be demanding, and taking action is often given higher priority than evaluating activities that have already been initiated. To ensure that Norway’s efforts on the country level are as effective as possible, results will be reviewed at two different levels, through the periodic reports from the missions and through an overall annual analysis of Norway’s work generally. Measuring the results achieved can however be difficult, for several reasons: the often broad and complex nature of human rights policy goals, the involvement and contributions of other actors, and the many external factors that also affect the results.

Textbox 7.3 Strengthening Norwegian capacity and expertise

A thorough understanding of human rights is essential if Norway is to play an active role in improving respect for human rights internationally and make its work at country level as effective as possible. Knowledge is also needed to ensure more systematic use of foreign and development policy instruments and to strengthen analytical capacity in the countries where the Foreign Service is active.

To improve knowledge sharing, the flow of information and exchange of opinions both within the public administration and with external actors, on-the-job training in the Foreign Service needs to be strengthened. This will put the service in a better position to follow up multilateral decisions and commitments at country level. Training in human rights issues, including human rights-based development cooperation, will therefore be strengthened.

Relevant tools for implementing the recommendations of this white paper will also be developed. Evaluation and evaluation routines will be strengthened so that the results and effects of different instruments and tools can be documented.

Textbox 7.4 Acute situations

The systematic approach described in Chapter 7.1 is mainly targeted towards long-term, planned work. However, crisis with large-scale consequences may arise suddenly, for example after a change of regime or in the event of a humanitarian disaster. The same methodical approach will apply in such cases, but time constraints will often introduce new challenges, and situational awareness will be particularly important as new scenarios arise. In crisis cases, it is vital to cooperate with other actors and coordinate efforts.

7.2 Instruments and tools for promoting human rights at the country level

In most cases, Norway’s work at country level will focus on cooperation with the authorities and/or civil society on the best ways for Norway to promote human rights in the country in question. This will be the natural starting point in countries that receive financial support from Norway, for example through development cooperation or the EEA and Norway Grants (described in chapter 4.4 and 6.1.4, respectively). One example of this type of approach is Norway’s support for Council of Europe action plans for countries that are falling short of their obligations as member states. These action plans are drawn up in close consultation with the country concerned, ensuring national ownership of each plan and a commitment to participate in its implementation.

In cases where the Norwegian government’s human rights priorities do not coincide with those of a particular country, cooperation with other local actors may be appropriate in order to counter violations of international human rights. If necessary, for example if a country is persecuting religious minorities, Norway is prepared to make use of negative tools such as public criticism and condemnation of the country’s actions.

In many countries and situations, the Norwegian authorities will combine cooperation with tools for a more confrontational approach. This may be done if it is possible to cooperate in certain areas of human rights and on certain measures, but not in a comprehensive manner, or if national authorities implement measures that the Norwegian Government condemns. The tools and instruments used may affect the access to partners with whom it is possible to cooperate. When a positive approach is possible, the Norwegian authorities will generally cooperate with national authorities or other major actors of society. If a more confrontational approach is necessary, Norway will make its views known to the authorities and at the same time seek cooperation with civil society and with countries and actors that share the Norwegian government’s objectives.

Situations can easily arise where the Norwegian authorities cannot openly discuss the measures they implement. This may have just as much to do with relations with the country in question as with relations with other actors Norway is supporting, such as human rights defenders. There may be cases where a critical approach is pursued behind closed doors, and where such dialogue would not be possible if the approach and the content of the criticism become publicly known.

There are many examples where the best results have been achieved in individual cases by working behind the scenes rather than by openly condemning the actors that have a key role in finding solutions.

7.2.1 Comprehensive approach

The Government will adopt a comprehensive and integrated approach that combines short- and long-term and positive and negative instruments and tools. Each situation must be assessed separately, and the Government will seek to adapt measures and responses, and make use of those considered to be most appropriate in each case.

The priorities of Norway’s human rights work, the tools and instruments used and the actors involved, will vary from one country to another. We are more strongly engaged in some countries than in others, depending on which challenges they are facing, the policies their governments are pursuing, and our bilateral relations with each country. In some cases, the Norwegian authorities have a broad-based engagement including talks at political level combined with financial and technical assistance. In other cases, the scope of our engagement is more limited. However, the Norwegian authorities invite all countries to take part in political dialogue on human rights issues at bilateral and/or multilateral level.

In cases where dialogue on human rights issues is not possible at bilateral level, it is natural to follow up the human rights situation in a country in multilateral forums. One current example is China. The human rights dialogue with the country is suspended, and the main channel for continuing our human rights engagement is currently the Universal Periodic Review process under the UN Human Rights Council. During the review of China in November 2013, Norway made recommendations concerning freedom of expression, the use of the death penalty and ratification of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

7.2.2 Cooperation and support

Human rights can be promoted through direct financial support for human rights measures in another country, or through technical assistance in the form of expertise and training, for example to improve the legal system. Financial support for the promotion of human rights is also provided through multilateral channels, particularly the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Textbox 7.5 Financial support entails obligations

Providing countries with financial support will enhance engagement and make it more legitimate to raise human rights issues with national authorities in such countries. Giving substantial financial support also entails special obligations. Norwegian support must not consolidate or strengthen the position of national authorities that are seeking to concentrate power without being willing to respect human rights. This follows from the ‘do no harm’ principle of development cooperation. The Norwegian authorities aim to base cooperation and dialogue on common goals that are in accordance with international human rights law. Chapters 4.4 and 6.1.4 describe conditions related to Norwegian financial support to different countries.

Other types of positive approach include financial support to and cooperation with civil society, media and freedom of expression organisations, support for the establishment of national human rights institutions, organising art exhibitions, taking part in conferences or research projects, and highlighting positive human rights developments. Support can also be provided for international work by individual countries. Cooperation on human rights issues with national authorities, exchange of experience with the public administration, business sector and academia in other countries, and organising joint events are other positive tools that can be used.

Further examples include support for international organisations that assist states to meet their human rights obligations and monitor compliance with them, and participation in the development of human rights instruments through the development of new treaty provisions or by proposing resolutions.

7.2.3 Criticism and sanctions

Negative instruments and tools include a range of responses from criticism and condemnation to the threat of and actual introduction of sanctions. Criticism or concern is often expressed behind closed doors, at senior official or political level. If it is considered more appropriate, Norway expresses its concerns openly, for example in the form of press releases or statements in multilateral forums.

In other cases, alternative approaches may be more effective, for example limiting or suspending political, cultural and economic relations. In certain cases, it may be appropriate to cancel high-level visits. Exceptionally, Norway may consider recalling diplomatic personnel or refusing to issue visas in response to violations of human rights. In certain situations, Norway has reduced the amount of aid a country receives, or the authorities have advised the business sector against investing in or trading with specific countries.

International law puts constraints on the use of certain types of negative instruments. For example, the UN Security Council is only authorised to adopt binding sanctions or decide to use armed force under Chapter VII of the UN Charter if a situation poses a threat to international peace and security. The threshold for the use of force is therefore very high. Norway has a duty under international law to implement sanctions adopted by the UN Security Council.

As a general rule, Norway consistently aligns itself with restrictive measures adopted by the EU Council, except in cases when political considerations indicate that this is not appropriate. The types of sanctions and restrictive measures most frequently applied are bans on supplying a country with military equipment and equipment that can be used for internal repression or providing technical and financial support related to such equipment, freezing assets belonging to listed persons, and travel restrictions for listed persons.

Several of these approaches are most effective when they enjoy broad international support and/or their implementation is coordinated, but in many situations it can be difficult to obtain sufficient support. The Government will advocate a coordinated response when this is considered to be appropriate.

7.2.4 Clear responses to serious violations of human rights

Allegations of serious violations of human rights should be assessed as thoroughly as possible before any negative instruments or tools are applied. This is best done in cooperation with international organisations, other countries, independent media and civil society. If the allegations can be verified, the Government will raise the matter in its dialogue with the authorities in the country concerned, and then issue a statement deploring the situation and demanding a halt to the abuses. If time permits, the matter may also be raised at multilateral level. Negative instruments generally have a stronger effect when a number of countries agree on a coordinated response, for example coordinated cuts in aid or support for UN resolutions requiring improvement of the situation and a threat of joint sanctions, which may involve a boycott or the use of force.

7.3 Selected country cases

The systematic approach described above governs our bilateral human rights efforts in individual countries. The precise approach taken is always adapted to the particular country and situation. The following describes our efforts vis-à-vis selected countries, and is intended to illustrate the different forms this work takes. It is not an exhaustive list of country cases or our working methods.

Angola

Norway cooperates with Angola in a broad range of areas. In particular, the Norwegian business sector’s substantial involvement is important. Our cooperation also includes human rights efforts based on the Angolan authorities’ recognition of the need to institutionalise a broader understanding of civil and political rights, as well as economic, social and cultural rights. In this connection, they have requested the Norwegian authorities’ support for various measures relating to education and training in human rights.

In response to this request, Angola and Norway established an annual bilateral consultation on human rights at political level in 2011. This has been an important supplement to the strong economic ties between our countries. These consultations have focused on related topics such as decent work and the role of trade unions and employers’ organisations in working life, but they also include topics such as domestic violence, where both countries recognise that they have challenges. In the 2014 consultation, the starting point for the discussion was the UN Human Rights Council Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Angola. Norway emphasised the importance of Angola following up the recommendations from the previous review cycle to allow greater freedom of expression.

In addition to these consultations, Norway is involved in practical project cooperation with the Angolan Ministry of Justice and Human Rights on capacity-building in the ministry, the association of judges, the bar association, the ombudsman, and other ministries and civil society organisations. Norway provides support for competence building at the law faculty of Angola’s largest university, with the aim of building up the expertise needed to offer courses in human rights in the future. In cooperation with Norwegian Church Aid and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), support is also provided to several NGOs that work with human rights issues.

Guatemala

After many years of civil war, a peace agreement was entered into in Guatemala in 1996, partly as a result of Norwegian support and facilitation. Despite the peace process and a transition to civilian rule, the country still faces considerable human rights challenges. Human rights defenders, journalists and representatives of civil society are particularly at risk. Impunity for violence and other crimes against these groups has demonstrably increased. Violence against women is another serious social problem.

Public security has inevitably become a priority task for the authorities. The existing security problems are intensified by a weak judiciary and police system. More resources are being channelled to penal institutions and the police rather than giving priority to prevention and social measures. Moreover, there is a high level of social conflict in Guatemala, for example in connection with the extraction of natural resources. Peaceful protests often end up in violent confrontations with the police and security forces. Recently, there have been attempts to address the serious human rights violations that were perpetrated in the past. However, critical civil society voices consider the authorities’ efforts in this regard to be mostly symbolic.

Support for the Maya Programme is one of Norway’s main focus areas in Guatemala. Through cooperation with various indigenous people’s organisations, the programme aims to advance the Maya peoples’ rights, education and political participation. This is very important work, as more than half the population are indigenous people whose rights are particularly at risk. The Maya Programme has achieved results in a number of areas. Cases concerning the right of consultation and land rights have been brought to court, law students have taken part in development programmes, bilingual education is now more widely provided in pre-school and primary school, and the political participation of Maya women and young people has increased.

Another way in which Norway is contributing to the rule of law is through its support to the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) – a UN body that was established in cooperation with the Guatemalan authorities. The Commission is combating criminal organisations and networks by holding their members criminally responsible for their actions. The cooperation between the Commission and the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions in Norway has resulted in a considerable reduction in impunity in recent years. The Commission also has a stabilising effect on the fragile legal system, which is suffused with corruption and strongly politicised.

The Norwegian Association of Judges, with support from the Norwegian authorities, has entered into cooperation with the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) and the Association of Maya Lawyers in Guatemala on strengthening the legal system through transfer of expertise and training, especially for judges and representatives of indigenous peoples. Key elements are fighting impunity, and ensuring the independence of the judiciary and access for indigenous people to the legal system. This is the first time that Norwegian and Guatemalan actors cooperate in this important field.

Hungary

The political reforms implemented by the Hungarian authorities since 2010 give cause for concern about developments in the country. A great number of new laws, including a new constitution, have been adopted in a very short time. The trend has been towards centralisation of power in the Government, combined with a weakening of the independence of the judiciary, the freedom of the press, the influence of the opposition and the freedom of action of NGOs.

New media legislation and preferential allocation of state advertising have seriously undermined the freedom of the press. In the annual World Press Freedom Index issued by Reporters without borders, Hungary ranked 23rd in 2010, but dropped to 64th place in 2014.After his re-election in April 2014, Prime Minister Orban declared that his vision is to establish an illiberal state where the interests of the nation, particularly economic growth, have priority over the freedom and rights of the individual. Civil society organisations that receive support from abroad – including those that are awarded grants from the NGO Fund in Hungary under the EEA and Norway Grants – are perceived as obstacles to the establishment of this illiberal state. It is a widely shared perception that the voluntary sector is under pressure in Hungary.

Undercurrents of intolerance of minorities, including anti-Semitism, opposition to the Roma people, and homophobia, are creating tensions in some segments of Hungarian society, even though almost none of the political parties – apart from the extreme right-wing Jobbik – have this as part of their official rhetoric.

Norwegian–Hungarian cooperation is generally good, and takes places through bilateral contact with the authorities, in multinational forums and through networks of NGOs. Norwegian companies help to make Norwegian and Nordic values better known and more visible in Hungary.

The Norwegian authorities have expressed concern about developments in Hungary in official statements, bilateral meetings and multilateral forums, including the OSCE Permanent Council. The concern is shared by many Western countries, including the other Nordic countries, the Netherlands and the US. Relevant international organisations, in particular the Council of Europe and the OSCE election observation mission, have also at times expressed strong criticism of key elements in the Hungarian democratic system, such as the constitution, the legal system and the election system. The Hungarian Government has had to heed some of the criticism, and certain concessions have been made. However, Prime Minister Orban has continued to launch scathing attacks on international organisations that criticise Hungary, including the EU.

The EEA and Norway Grants are an important instrument for bilateral cooperation with Hungary in the field of human rights and democracy. The total amount allocated through this mechanism by Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein for the period 2009–14 is EUR 153 million, or approximately NOK 1.26 billion. Programmes under the EEA and Norway Grants focus on improving the situation of vulnerable groups (including the Roma people), combating hate speech, corruption, and anti-Semitism and xenophobia, and promoting gender equality, freedom of expression and good governance. A separate NGO fund has been established to strengthen civil society. Norwegian partners are involved in the implementation of some of these programmes.

As a result of Hungary’s violation of the agreements on the management of the Grants, Norway suspended payments to Hungary under the scheme in May 2014. The reason was that the Hungarian Government, in breach of the agreements they have entered into, unilaterally moved implementation and auditing of the Norwegian funding outside the central government administration. The programme for civil society and a programme for adaptation to climate change have been exempted from the suspension, as the Hungarian authorities are not responsible for the implementation of these programmes.

Indonesia

The Norwegian authorities and other Norwegian actors are engaged in broad cooperation in Indonesia in a range of areas, including climate change and deforestation, environmental and energy issues, human rights, as well as overall development cooperation and a considerable business sector engagement. In order to strengthen this cooperation, an agreement was entered into in July 2013 to establish the Joint Commission between Indonesia and Norway.

Norway’s human rights dialogue with Indonesia, which was established in 2002, has become a cornerstone of the bilateral relations. Indonesia is steadily gaining greater regional and international influence. It is of considerable foreign policy significance that the country continues to develop its democracy and strengthen respect for human rights. The human rights dialogue gives the Norwegian authorities a unique opportunity to contribute to these developments. The longstanding cooperation with Indonesia has created mutual trust between our countries and fertile ground for open, candid discussions, even on difficult topics.

Textbox 7.6 International Expert Consultation on Restorative Justice for Children

In 2013, Norway, Indonesia and the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Violence against Children hosted the International Expert Consultation on Restorative Justice for Children in Bali. The idea for this initiative emerged under the human rights dialogue between Norway and Indonesia. The Consultation was attended by international experts with experience of this issue from all continents. Indonesia had more than 30 participants with different roles in the implementation of the new Indonesian law on children in conflict with the law. Among the participants from Norway were representatives of the Ombudsman for Children, the Mediation and Reconciliation Services, the police and the Ministry of Justice and Public Security. They shared Norway’s experience of helping children and young people who have been in conflict with the law to return to society, including alternatives to prison sentences for young criminals. The Consultation was a success. One of the outcomes was a thematic report by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Violence against Children, which was presented to the UN General Assembly in the autumn of 2013 and to the UN Human Rights Council the following year. This report is now used as a reference work in the Special Representative’s work to address this issue all over the world.

The dialogue consists of talks at political and senior official level, as well as discussions on thematic issues at expert level involving representatives from the authorities, academia and civil society. In addition, we are engaged in expert and project cooperation with thematic links to the political dialogue. The Norwegian Centre for Human Rights has considerable expertise on Indonesia, and is engaged in a number of projects stemming from the dialogue, with funding from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The current expert and project cooperation has been a key part of Norway’s engagement with Indonesia, and includes a broad range of partners in both countries, including students, academics, civil servants, journalists, and members of civil society and the armed forces.

Through the cooperation with Indonesia under Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative, important results have been achieved in the field of human rights, among them greater recognition of indigenous peoples’ rights, increased access to information and more opportunities to influence decision processes of importance for the living conditions of indigenous groups.

Myanmar

Reforms and greater openness in Myanmar in recent years have led to improvements in the human rights situation in many areas. Many of the violations of human rights that have taken place have been in the parts of the country affected by armed conflict. The many ceasefire agreements that have been signed have improved the situation for many people. The release of political prisoners and a more democratic legislative process are also positive developments.

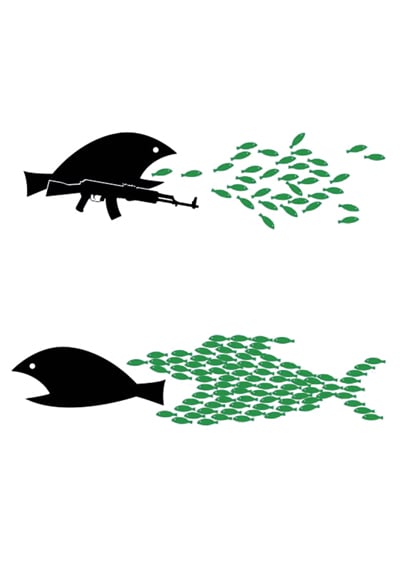

Figure 7.3 Eshel Yuval, Israel

On the other hand, challenges remain relating to marginalisation of minorities, ethnic and religious conflicts, inadequate rule of law, corruption and poor governance. Perhaps the most serious is the situation in Rakhine, where there is a high level of tension between the Buddhist Rakhine people and the Muslim Rohingya people. A large number of Rohingya are internally displaced, and the humanitarian situation is serious. At the same time, the distrust of both the international community and the government authorities is so strong that it is difficult to ensure humanitarian access and freedom of movement. The Norwegian authorities are supporting efforts to improve the situation in Rakhine, through both humanitarian aid and support for actors who can exert a moderating influence.

The Norwegian authorities have had a broad engagement in Myanmar for many years, providing support for the democracy movement and other agents of change, as well as humanitarian assistance. Since the reform process started to pick up speed in 2011, under the governance of President Thein Sein, the direct support to Myanmar has increased. A Norwegian embassy was established in Yangon in the autumn of 2013, which has further increased the breadth and depth of Norway’s engagement in the country. Key priorities include long-term development cooperation, sound management of natural resources, peace and reconciliation efforts, support for civil society and agents of change, and the establishment of Norwegian business operations within a framework of corporate social responsibility.

The Norwegian authorities have developed a relationship of trust with the Myanmar authorities, not least through the explicit support for the peace process. We also make use of this trust to raise difficult issues, including human rights challenges. Our aim is that Norway’s engagement in Myanmar will help to improve the human rights situation in the country both through a focus on human rights in their own right and in connection with the peace process and the democratic reforms. Norway supports the proposed establishment of an office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Myanmar. If this goes ahead, the office could provide valuable guidance for efforts to improve the human rights situation and assist the authorities in addressing challenges in this field.

Russian Federation

Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and destabilisation of eastern Ukraine have created a completely new situation in Europe. Russia’s relations with its neighbours have changed. Norway’s relationship with Russia has been affected both by Russia’s violation of international law and by developments in recent years within the country towards more authoritarian rule. These developments have brought human rights increasingly under pressure.

Textbox 7.7 Continual restrictions on rights

Since Vladimir Putin’s return to the Russian Presidency in 2012, many restrictions have been imposed on civil and political rights. A number of legislative changes have been made, including a more stringent law on espionage and treason, a new blasphemy law and the introduction of criminal liability for defamation. Legislation regulating protests and public gatherings has been tightened several times. NGOs involved in so-called ‘political activities’ that receive funding from abroad have to register themselves as ‘foreign agents’. The ban on ‘propaganda of non-traditional sexual relationships’ is increasing the marginalisation of sexual minorities in the country. Moreover, these laws have been formulated to allow for arbitrary interpretation and application, and high maximum penalties have been introduced in the form of both heavy fines and long prison sentences. It has been pointed out that several of these legislative changes are contrary to the Russian Constitution and in violation of Russia’s obligations under international law.

Freedom of expression has been considerably reduced in recent years, and even more so since the annexation of Crimea. The intelligence and security services have been given broader powers. Websites may be closed down without a court decision. Bloggers are subject to the same requirements as commercial media, but without the same rights to access to information. Russian state media, particularly television channels, give little opportunity for critical voices to speak out. Russia has plummeted on freedom of the press indexes in recent years, and in 2014 was ranked in 148th place on the World Press Freedom Index.

The arena for genuine political competition has been narrowed, despite an easing of the rules for registering political parties in 2012. The number of elections has been reduced and the conditions for taking part have become more difficult. Members of the opposition have had their homes searched and have been put under pressure by the police and the intelligence services. They have been accused of extremism, corruption and economic crime, particularly those who have played a prominent role in protests.

The authorities have used harsh methods to fight the insurgency in the North Caucasus. Violations of human rights continue to take place, including abductions, torture, disappearances and damage to suspects’ property. Russia has on several occasions been convicted of such violations by the European Court of Human Rights.

Russia has voluntarily taken on a number of human rights obligations through its membership of international organisations, particularly as a party to the European Convention on Human Rights. Its membership of the Council of Europe, the OSCE and the UN also entails expectations of maintaining high human rights standards.

In their contact with Russia, the Norwegian authorities systematically raise the need to respect human rights in accordance with the obligations Russia has taken on. The importance of the principles of the rule of law and a free and active civil society are also emphasised. The Norwegian Government also actively supports Russian civil society, which is under severe pressure (see Box 7.7). Cooperation between Russian and Norwegian organisations is important for strengthening civil society in Russia and for counteracting the negative developments in human rights in recent years. This applies not least to environmental efforts; Russian environmental organisations report that conditions for their activities have become more difficult in recent years. It is in Norway’s interest to prevent forces for good from becoming isolated. Developments in Russia may make it difficult to strengthen cooperation between civil society organisations in Norway and Russia in the field of human rights. At the same time, it is important to support efforts to promote an open and democratic society within the existing framework for project cooperation with Russia. Priority is given to cooperation between Norwegian and Russian NGOs that promote human rights. In particular, support is provided for projects that enhance legal safeguards and support human rights defenders, environmental NGOs and human rights education. The Norwegian authorities will continue to provide this vital support as long as the political situation allows.

South Sudan

Fragile states tend to be weak, to lack legitimacy in the eyes of the population, and to have insufficient control over their territory. Inequitable distribution of wealth and resources and socio-economic polarisation are also common, and elites tend to take far more than their fair share. There may be divisions along ethnic lines. Systems for holding political leaders accountable are weak or non-existent.

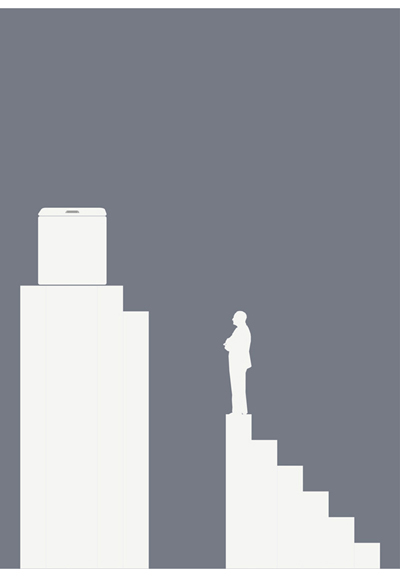

Figure 7.4 Sepideh Riahi, the US

Ever since the Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed in 2005, South Sudan has shown all the characteristics of a fragile state. Even when the country gained independence in 2011, after six years of massive international aid, the situation had changed very little. Weak government structures, lack of political legitimacy, inequitable distribution and deep-seated internal tensions were some of the challenges the country faced. Since then developments in many areas have gone in a negative direction. The ambitious state- and capacity-building project never really got off the ground. To begin with, this was due to extremely tense relations with Sudan, and subsequently to the internal conflict within the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), which has virtually become a civil war. Institutions that are crucial for safeguarding and protecting the citizens’ rights were already weak. The ongoing conflict has weakened them further, and in most parts of the country they now hardly function at all. The human rights situation has worsened dramatically. Several reports conclude that crimes against humanity may have been committed by both parties to the conflict. Humanitarian access is often prevented by the warring parties, and an increasing number of aid workers are being been killed.

For Norway and other development partners, these developments give rise to major challenges in our dialogue with the authorities on economic, political and social development, including human rights. Before the latest crisis erupted in December 2013, there were established forums and meeting places for contact between the authorities and development partners. The work on a new framework for aid, the New Deal Compact, had almost been completed. This provided a platform for systematic dialogue and discussion on human rights and good governance. Since the start of the current crisis, this has hardly been in use.

Norway has therefore emphasised the use of multilateral mechanisms and institutions to gain the greatest possible weight in the dialogue with the authorities on these issues. The efforts in the UN Human Rights Council are very important in this respect. The critical situation for human rights is addressed in meetings with the South Sudanese authorities at all levels. This work is coordinated closely with other donors in order to ensure a united and unambiguous message with clear demands and expectations of the parties to the conflict. Together with the US and the UK, Norway is part of the troika that provides economic and political support to the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) in Eastern Africa and the African Union (AU). It is indispensable to ensure a strong regional involvement in the efforts to find a solution to the crisis. It also provides a platform for close dialogue with IGAD and the AU on the human rights situation in South Sudan.

The developments in South Sudan illustrate how difficult it can be to bring about lasting change that ensures security and stability for the population in fragile states. Supporting fragile states requires perseverance and high tolerance of risk. The Norwegian authorities must systematically monitor the human rights situation and raise concern over abuses carried out by the authorities and any other groups with a clear voice. The rights perspective is integrated into both our development cooperation and our humanitarian aid.

Tunisia

Since the revolution in 2011, Tunisia has made progress in a number of areas in terms of human rights. The country soon acceded to several international human rights conventions and withdrew reservations from other conventions that had been made by the former regime. In January 2014, Tunisia’s national assembly adopted a constitution that ensures gender equality, freedom of religion or belief and freedom of expression, as well as an independent judiciary and a civil state. The constitution also establishes that the international conventions Tunisia has acceded to take precedence over national legislation. Norway has supported the development of the new constitution through cooperation with the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe.

The most important development since the revolution is the strengthening of freedom of expression and freedom of assembly and association. The Tunisian press (both paper and online) has experienced tremendous growth since the revolution. A bill guaranteeing freedom of the press was presented as early as 2011, and in 2012 an independent body was established for the press and the media. Challenges remain in relation to establishing legal safeguards for journalists’ rights, preventing arbitrary imprisonment for opinions expressed, and providing conditions that are conducive to a trustworthy, independent press corps.

Whereas civil society was subjected to strict control and surveillance under the former regime, there are now a number of independent organisations that are active within various sectors. Peaceful demonstrations are allowed, and the social dialogue in Tunisia has been strengthened through solid tripartite cooperation.

There is still a long way to go with respect to reducing regional disparities and ensuring equal social and economic rights for the entire population. Likewise, there are challenges related to torture during detention and in prisons, the independence of the judiciary, and the holding of democratic, transparent presidential and parliamentary elections.

Norway does not have an embassy in Tunisia. Nevertheless, the Norwegian authorities began providing support for a democratic transition at an early stage after the revolution in 2011. This support, which is mainly channelled through international organisations and regional programmes, promotes inclusive economic development, transitional justice and legal reform, women’s rights and social participation.

Tunisia is still in a critical phase and is facing major political, economic and security challenges. Continued international support is vital. So far, Norway’s engagement has been relatively limited. In order to contribute to further favourable developments, Norway hopes to strengthen its cooperation with Tunisia in the years ahead.

United Republic of Tanzania

Tanzania has been one of the most important partner countries for Norway’s development cooperation for decades. Today, it is the fifth largest recipient of Norwegian aid. Tanzania is currently at a political crossroads. Significant gas discoveries could give the country large revenues in 15–20 years’ time. Its multiparty democracy is gradually maturing, and the constitution is currently subject to an extensive reform process, where the format of the union between Zanzibar and the mainland has been up for discussion. At the same time, there have been tendencies to unrest and violence, such as the acid attacks on foreigners in Stone Town and the bomb attack in Arusha.

Norway’s development cooperation with Tanzania is in a period of transition, with a view to supporting Tanzania’s own goal of becoming aid independent. The main focus areas are oil for development, clean energy, cooperation under the Norwegian Climate and Forest Initiative, agriculture and food security. There will be a gradual change to Norway’s approach, with an increasing focus on private sector development and local spin-off effects of foreign investments. Good governance, the fight against corruption and a rights-based approach to programming are cross-cutting considerations in all aspects of Norway’s engagement in the country. In addition, we are providing support for a number of measures aimed at promoting democratisation and the transition to a true multiparty democracy. Our support for democratisation and human rights is primarily channelled through the UN, but we are also providing support to civil society, independent media and inter-religious dialogue.

The main dialogue between donors and the authorities on human rights and good governance has taken place in connection with the budget support governing mechanisms, where these issues are among the ‘underlying principles’. Although 2014 was the last year in which Norway provided budget support to Tanzania, the ongoing follow-up of the bilateral development cooperation will provide a number of opportunities for raising and highlighting important human rights related issues in our dialogue with the authorities. Relevant human rights perspectives are integrated into the dialogue on development policy priorities both in the negotiations on agreements and in the dialogue on implementation. Norway clearly articulates demands and expectations with regard to fighting corruption, increasing tax revenue, greater transparency, inclusive public participation, and sustainable management of natural resources in its dialogue and agreements with the authorities.

In addition, we make use of processes such as the African Peer Review Mechanism and UN Human Rights Council Universal Periodic Reviews as a platform for dialogue. Civil society is an important actor in the national human rights dialogue. Support is provided for NGOs that monitor and report on human rights, take part in election observation and provide free legal aid. Support is also provided for the Media Council of Tanzania, which promotes freedom of expression. Norway also supports civic education and public information efforts under the auspices of the authorities and civil society organisations. This includes support for universities and other institutions that are involved in studies on governance and human rights issues. An example of follow-up in a particular sector is the focus on the inclusion of indigenous peoples in processes related to the Climate and Forest Initiative. Support is provided for efforts to address sensitive issues, such as tensions between religious groups and land rights, through inter-religious dialogue and establishment of a civil society forum on land rights.

7.4 Considerations and dilemmas

In promoting human rights, it is sometimes necessary to strike a balance between different considerations within the framework given by international human rights law. Terror and extremism are serious threats to human rights that must be combated in a manner that respects human rights. Certain human rights are absolute, such as the prohibition of torture. This means that countries must not engage in torture under any circumstances, not even on suspicion of serious crimes. Certain other rights may be restricted in exceptional cases, but only if the following three conditions are all fulfilled: the restriction must have a legal basis in national legislation, it must serve a legitimate aim, and it must be necessary in a democratic society. Examples of legitimate aims are interests of national security or public safety, protection of public health, or protection of the rights and freedoms of others. Surveillance of individuals who are suspected of terrorism is an interference on the right to privacy, but it is not a violation of human rights if the conditions mentioned above are met. However, torture of individuals suspected of terrorism is prohibited in all circumstances.

It is in Norway’s interest, both politically and economically, that human rights are respected throughout the world. Short-term costs are sometimes necessary to accept in order to promote long-term goals. Some countries may react to what they consider to be interference in the area of human rights by breaking off political dialogue, introducing barriers to trade and investments, or actively opposing Norway’s positions in international organisations. However, in a long-term perspective there should not be any contradiction between human rights on the one hand and political and economic considerations on the other. Respect for human rights is crucial in order to reach durable solutions that provide a sound basis for lasting economic and political cooperation.

Building trust between the parties to a conflict and helping to create platforms for dialogue are vital aspects of Norway’s peace and reconciliation work. In this type of situations, the Norwegian authorities are usually required to keep a long-term perspective, and must sometimes show restraint in terms of publicly calling for perpetrators to be brought to justice, or condemning one of the parties to the conflict, on account of Norway’s role as facilitator. However, in peace processes Norway is always a driving force for ensuring that human rights are included in the negotiations, and works actively for negotiated agreements that safeguard the rights of the victims and of parties or population groups that are not represented at the negotiating table. This is important for any agreement to be respected in the long term.

Norway’s human rights efforts are not limited to selected countries; in principle, they apply to all the countries. Media coverage of human rights tends to focus on the most serious and massive problems, such as gross violations of legal safeguards or persecution of religious minorities. The Foreign Service, however, takes a broader perspective on human rights. Supporting favourable developments may be just as important as criticising a country for negative incidents. If Norway’s engagement was limited to measures targeting the most difficult states or the most serious human rights violations, that would be unfortunate for a number of reasons. One of them is the question of legitimacy: if all focus was on the countries with the greatest challenges, the Norwegian authorities would be likely to be criticised for not taking the problems in Western countries seriously. Another reason is short-term results: if Norwegian authorities only focus on gross violations, there may be fewer opportunities to achieve improvements in more limited areas. Therefore Norway criticises both the US and Iran for their use of the death penalty, and is just as likely to support other countries’ authorities in their work to develop the education sector as to criticise them for neglecting the justice sector. Norway’s efforts are often greatest in areas where Norway has particular strengths, including knowledge pools in academia, the media and civil society, historic ties from earlier missionary or aid work, strong involvement through business or civil society, or special relations to the country in question.

Another important consideration is how to address human rights violations, and what instruments and response mechanisms are best suited for doing so. In critical situations, protesting loudly against human rights violations can save lives, and may be perceived by civil society and the population groups that are oppressed as vital support for their work. Loud protests may be symbolically important and send an important signal to other regimes and oppressors. At the same time, open public criticism may provoke some states and result in the authorities breaking off the dialogue with Norway, thereby limiting the opportunities for exerting influence. It is important to strike a good balance between clear public messages and quiet diplomacy, while preserving Norway’s integrity and credibility.

Choosing partners for cooperation may also involve difficult considerations. Providing funding to non-governmental organizations may be perceived as criticism of the national authorities, or even as undermining the recipient country’s legitimate regime. This tends to make political dialogue with the country more difficult. This may be particularly true of support for democratic development, which is often perceived as support for the opposition. Nevertheless, support for civil society is a key component of the Government’s foreign and development policy. Thus, the question of how to determine how much support to provide, especially in relation to support for other areas, is important. Support that is over-dimensioned or too obvious can tend to be self-defeating. Providing support to a number of sectors, including support for government institutions, may help reduce the degree of sensitivity, but at the same time fragmentation should be avoided. Vulnerable groups, such as religious minorities, may be in direct danger if they are closely identified with Western countries and/or religions. Thus a further challenge is how much information about this type of support Norway can share with the authorities, and how the Norwegian authorities use this information in national and international dialogues.

Figure 7.5 Lakhdar Mohamed, Morocco

Active and responsible involvement by the business sector can have a direct and positive impact on the human rights situation in the countries concerned. The presence of Norwegian companies in a country can also help to facilitate constructive dialogue between Norway and the country’s authorities. Norwegian authorities seek to establish a political dialogue in which it is possible to communicate clearly and address human rights violations without undermining cooperation on other fronts. Choice of priorities is vital, as is linking some of the human rights efforts to business cooperation. This may include topics such as decent work, worker participation in decision-making, impact assessments (for instance in relation to the rights of indigenous peoples), education, and freedom of expression and information. Other examples involve knowledge transfer, through programmes such as Tax for Development and Oil for Development, which also include human rights. Norway’s message is that democracy, human rights and the rule of law are prerequisites for stable economic growth, and in the interests of both the business community and the country itself. Many of the countries with vast energy resources are governed by politically oppressive and socially unjust regimes, which can make it difficult for Norwegian businesses and the Norwegian authorities to enter into cooperation with these countries. Investing and doing business in other countries entails responsibility. This is discussed in more detail in chapter 4.5.

Although human rights are indivisible, and civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights are intertwined, they are weighted differently in different countries. It is difficult to make people aware of their own rights and those of others, and to generate engagement for these rights, in countries where the economic and social situation requires most people to spend most of their time meeting their primary needs. This is the case in many of the countries where respect for human rights is weak, and it applies particularly to civil and political rights, which authorities may perceive as threatening their own position. Too strong a focus on civil and political rights can provoke resistance. In an international context, the authorities in many countries are most interested in talking about economic and social development. It is important in this context to emphasise that the economic, social and cultural rights are to be implemented without discrimination, and that they are intertwined with civil and political rights. The links between the challenges a country is facing and the human rights situation in that country must be highlighted.

The Government will seek to address the considerations and dilemmas involved in human rights work with openness and dialogue. A guiding principle for the Government is to make it clear that dilemmas may arise, and set out the reasoning behind the decisions that need to be made. There should never be any doubt in the international community as to Norway’s position on human rights issues.

Priorities:

use a systematic approach to bilateral efforts, based on the human rights commitments and obligations of the countries concerned, and in line with our multilateral efforts;

actively use the human rights obligations these countries have committed themselves to, as well as reports and recommendations from treaty bodies, global and regional special procedures and the Universal Periodic Reviews of the UN Human Rights Council, in bilateral efforts;

pursue a policy based on openness and dialogue in dealing with dilemmas and difficult considerations, without compromising on Norway’s human rights obligations.