3 Definitions and the current situation

Figure 3.1

Public sector innovation is not a new policy area, although it has been more on the agenda in recent years. It is also relatively new as a research field. A review conducted in 2016 shows that more than half of the studies on public sector innovation were published after 2010.1

3.1 What is public sector innovation?

3.1.1 Definition of public sector innovation

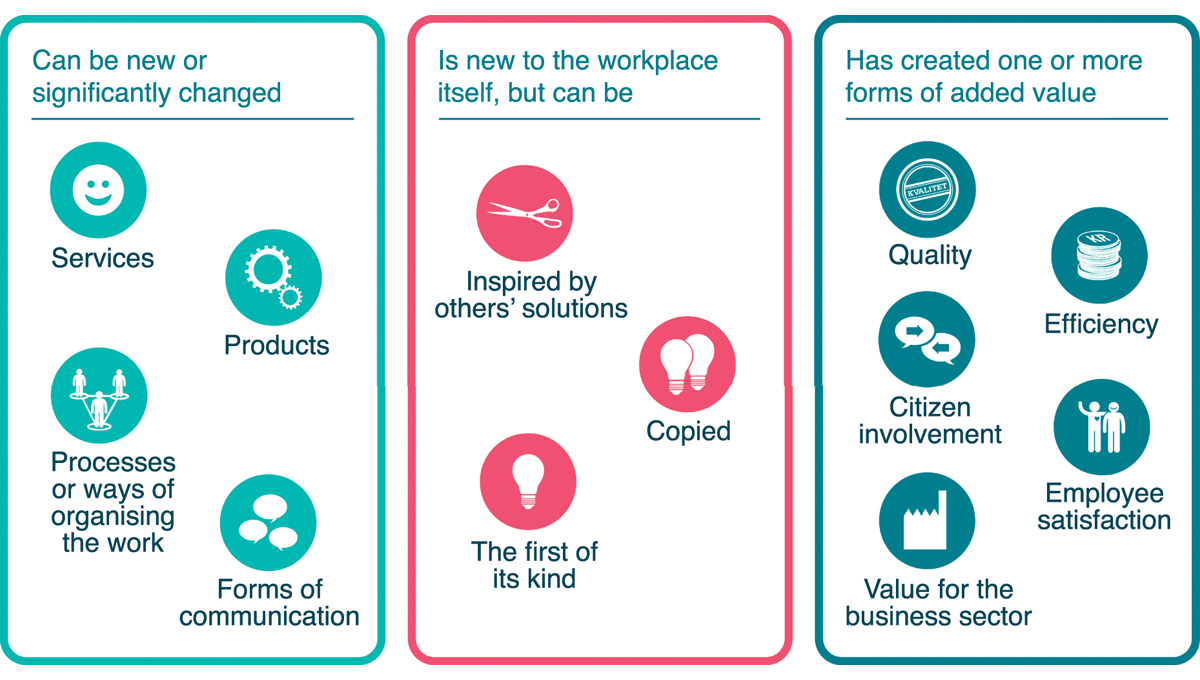

Innovation means implementing something new that generates value for people and society.2 In this report, we use the OECD’s definition as our point of departure, where public sector innovation is defined as follows:

Public sector innovation can be a new or significantly improved service, product, process, organisation or form of communication. That the innovation is new means that it is new to the organisation in question; it may nonetheless be known to and implemented by other organisations.3

The definition tallies with the definition of innovation as something ‘new and useful that has been utilised’, which is used by the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS) and many public agencies (Figure 3.2).4 Furthermore, it is assumed that public sector innovation can also take place in systems, structures and in larger areas of society, often called transformative innovation.

Figure 3.2 Types of innovation in KS and Difi’s innovation barometers

Source KS

User centricity

Users are citizens, public agencies, private enterprises and the voluntary sector.5 Users should perceive public services as seamless and integrated, regardless of which public agency provides them.6 One of the goals of the State’s communication policy is that people are invited to take part in formulating policies, schemes and services.7

3.1.2 Identify opportunities and define needs instead of solutions

Identifying new opportunities and devoting time to clarifying the actual needs are important preconditions for public sector innovation. A successful process should not start by defining a detailed solution with clear specification requirements, but be open to the possibility that the solution may not have been invented or developed yet. It should also be open to the possibility that the problem or need may prove to be different to what was first assumed, or that it may be bigger and involve other parties. The solutions that were first identified are not necessarily the best way to solve the problem. Therefore, needs rather than solutions should be defined first. Involvement is important when mapping needs, because they can be the needs of citizens or users, industry players, civil society or the public sector itself. The Digitalisation Council, a consultancy service for all state sector managers, has noted that failure to involve internal and external users at an early stage is a challenge in the public sector.8

Public procurement is an area where defining needs rather than solutions is particularly important to encourage innovation. The public sector purchases goods and services worth more than NOK 560 billion every year. How the public sector spends its funds is of great importance, both to the degree of public sector innovation and to the development of the business sector.

Public procurers are responsible for spending taxpayers’ money sensibly, and finding new ways of doing things is not necessarily easy. The easiest, most convenient choice is to do what they have always done or to order goods and services that seem to work satisfactorily.

If public agencies order the same goods and services tomorrow as they did yesterday, this limits public sector innovation and provides little room for new, interesting ideas that can save resources or develop services and offerings that have the desired effect. It is therefore important to have a culture in the public sector that encourages new ideas and fresh thinking, and where people have the courage to carry out tasks in new ways, be curious and keep an open mind to possible solutions.

A needs-based approach and early testing

A needs-based approach combined with early testing of unfinished solutions makes it possible to change course during a development process. Fail fast is precisely about testing new and unfinished solutions before you have put too much time and money into developing them.

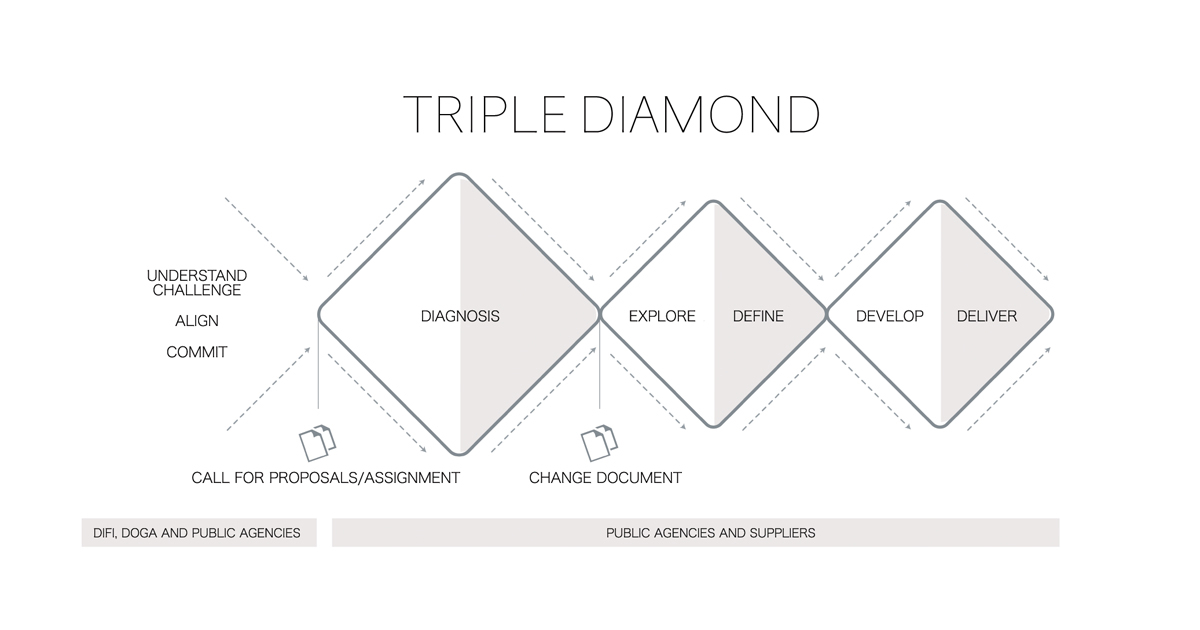

One way of illustrating the work method that involves needs diagnosis, exploration and testing is the triple diamond (Box 3.1), which is the model used by the Norwegian Digitalisation Agency9 in projects under StimuLab, the stimulation scheme for innovation and service design (Chapter 8).

Textbox 3.1 The triple diamond

The triple diamond shows the phases of a process comprising needs definition, exploration and development.

The diagnosis phase is strongly emphasised in the model and involves the participation of several parties already at this stage. The aim of the diagnosis phase is to achieve a common understanding of the issue to be resolved in the process, which ensures that the solution to be developed or procured is based on genuine needs and not assumptions. Diamond number two illustrates the phase during which ideas are developed, users involved and different concepts tested, to arrive at the solution that best addresses the task at hand.

The final phase is the phase in which the chosen solution is further developed, prototyped and simulated, before it is implemented.

Figure 3.3 Triple diamond

Source Norwegian Digitalisation Agency, StimuLab

3.1.3 Incremental and radical innovation

Innovation is a term used to describe change and development that represent a break with previous practice. This distinguishes innovation from continuous change and other development work. You have to do something else, not just improve what you are already doing.

Innovation can take place in big leaps, through radical innovation, or step by step through incremental innovation. Incremental innovation is gradual, but nonetheless represents a break with previous practice. For each step, the degree of risk and uncertainty is lower than in the case of radical innovation. The sum of several incremental innovations can amount to a radical change. One example of this is the work of the Norwegian Tax Administration, which, through incremental changes over ten to twenty years, has radically changed how people submit their tax returns (Box 3.2).

Radical innovation is about fundamentally changing ways of providing services or developing products. Radical innovation constitutes a bigger break with the status quo and thereby entails greater risk and uncertainty during the development phase.

Radical innovation can turn entire organisations or industries on their heads, change the rules of the game or people’s expectations. In the private sector, Airbnb challenges the rules of the hotel market, while Vipps does the same in the banking market. These players create added value for their customers through cooperation in value-adding networks. In the public sector, hospitals and libraries, among others, are undergoing radical changes. With the help of technology, hospitals are moving parts of their services into the patient’s home.10 Libraries have gone from being places to find, lend and return books to social arenas for experiences, creative activities and knowledge sharing. Going forward, new technology such as artificial intelligence can lead to radical changes that will have a huge impact on the way the public sector works.

The public sector has come a long way with incremental innovation. In the Government’s view, incremental innovation will not always be sufficient if we are to utilise the possibilities offered by new technology such as artificial intelligence and data sharing. Nor will it be enough as regards the challenges facing the public sector, where changes are taking place more rapidly than previously assumed. The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that it is possible to develop solutions faster together.

Textbox 3.2 The tax return: an incremental and radical innovation

The use of information technology in the tax area goes a long way back. Tax calculation was one of the most important applications of the intermunicipal punch-card stations established in the 1950s. In the 1960s, the Directorate of Taxes developed services for machine calculation of taxes at the central level. During the 1980s, it became possible for employers and banks to submit information to the tax authorities in a machine-readable format. In the 1990s, this information was used to devise a simplified tax return for taxpayers who could confirm that they had received correct, complete annual statements. Following extensive efforts to raise the quality and amount of data, it became possible for all wage-earners and pensioners to correct and supplement the information received by the Tax Administration from other sources. This meant that the tables had turned, with the agency now providing the information and the taxpayer verifying it. Electronic submission via the internet was established in the early 2000s, and from and including 2008, taxpayers who had no changes to report no longer needed to submit their tax return.

From 2017, such automatic processes were described as the primary track in legislation, and not as an exception to the manual track. From and including 2020, most wage-earners and pensioners can use a new dialogue-based tax return. It reflects the fact that nearly everyone now uses their mobile phone, tablet or computer to review and process their tax return. In a digital dialogue, taxpayers are asked specific, relevant questions based on what the Tax Administration knows and the actions taken by the taxpayer. Each taxpayer must actively consider the questions and can answer them there and then. The innovation lies in the transition from correspondence to a digital dialogue with the taxpayer. The intention is to actively involve the individual taxpayers in their tax affairs and ensure that the tax return is as complete and correct as possible before submission.

Source Ministry of Finance

3.1.4 Transformative innovation

Transformation or transformative innovation means whole-system changes in an area. One example is the transition to a greener society and economy (‘the green transition’), and meeting the ambitious global and national climate targets, which will require substantial changes on the part of the population, businesses, the public sector and organisations. Transformative innovation will always include an element of radical change and it will require experimentation, research and changes in many areas at once. Local, regional, national and international efforts must be coordinated.

The public sector can be a driving force for transformative innovation, among other things by setting a direction for research and innovation efforts, clearly communicating needs and possibilities, and expecting innovative approaches to known challenges. This approach to innovation is often referred to as the third approach to or the third-generation of innovation policy.11

Digital transformation means changing the fundamental ways in which organisations and enterprises perform tasks with the help of technology. This approach can lead to a need to change the organisation, transfer responsibility, rewrite regulations or redesign processes.12

3.1.5 Several types of innovation work together

Service and product innovation is what many people associate with innovation. The public sector can innovate in relation to its own services, as illustrated by Asker Welfare Lab (Box 10.2). The public sector can also purchase or co-create innovative products and services, as in the case of innovative procurements (Chapter 11).

Product and service innovation can give rise to a need to change work methods. Home healthcare services rather than hospital care, for example, require doctors and nurses to work in new ways. This is process innovation and organisational innovation, which means new or changed work methods and processes within an organisation.13

Implementing or starting to use an innovation can also trigger a need for changes in the formal and informal framework of the organisation in question, such as decision-making and governance regimes, budgeting and reporting procedures, the funding system and informal procedures, norms and values. When libraries become social arenas, it can for example be more useful to measure the number of people attending events rather than the number of books borrowed.

Several institutions from different sectors or levels of the public administration can be part of the same innovation project, for example both a hospital and a municipal home nursing care service. That gives rise to a need for simultaneous change, or innovation, in several organisations and at several levels of the public administration. Disagreements between professions may also play a part in the process. Understanding this complexity is of great importance if the implementation of public sector innovation is to be a success.

3.2 Well positioned for innovation

Norway is well positioned for public sector innovation. There is high educational attainment, high use of digital services and products, and a high level of trust between citizens, the public sector and public authorities. The Norwegian labour market model, characterised by extensive cooperation between the social partners, is often seen as a precondition for the good results achieved: a well-functioning labour market, a good working environment, low unemployment and high labour force participation. That puts us in a good position for public sector innovation.

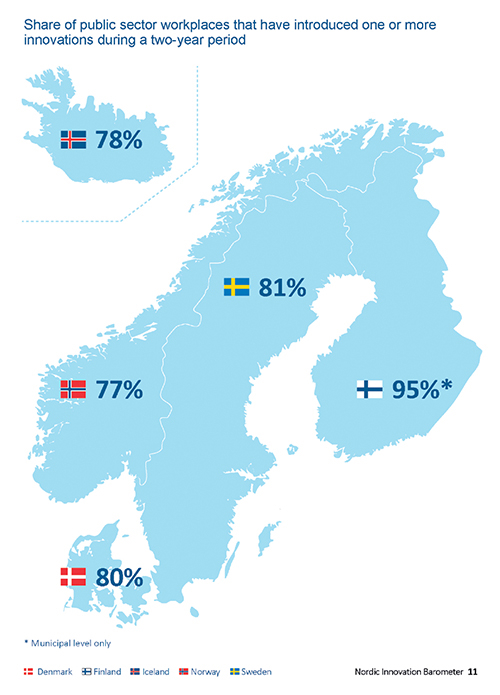

In the Innovation Barometer surveys for the central and local government sectors, 74 per cent of municipalities and 85 per cent of central government agencies report that they have introduced at least two innovations in the past two years.14 That is approximately on a par with our Nordic neighbours (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4 Innovations in the past two years

Proportion of managers reporting that their organisation/workplace has introduced one or more innovations in the past two years. The type of innovations is not specified. The figure for Norway is a weighted average of the state and municipal results.

Source Measuring New Nordic Solutions, Innovation Barometer for the Public Sector. Report 2019.

Public sector innovation takes place within a political framework, where the top-level leaders are government ministers and elected politicians in the Storting, the municipalities and the county authorities. The core values of public administration are democracy, the rule of law, professional integrity and efficiency.15 Transparency, accountability and verifiability promote these values.

3.2.1 Sectors and administrative levels

The government administration is organised according to thematic areas. That means that each minister is responsible for matters that fall under their ministry and subordinate agencies. The advantages of this division of responsibilities is that responsibility is assigned to experts in that specific field and that roles and responsibilities are clearly assigned. On the other hand, a rigid interpretation of sector responsibility can be an obstacle to necessary coordination and innovation.

Innovation often requires efforts by and coordination between several different administrative levels and sectors. At the same time as the public sector and Norway are well positioned for innovation, it has been pointed out in several contexts that the conditions for cooperation are demanding. This is especially the case when investments come from one sector, while the benefits are seen in another.

3.2.2 A diverse local government sector

There were 356 municipalities in Norway as of the end of 2020. The municipalities are diverse in terms of population, size, location and expertise. About half of the municipalities have a population of less than 5,000, while more than 120 have fewer than 3,000 inhabitants. Twenty municipalities have a population of more than 50,000.

The municipalities have wide-ranging authority and a high degree of local autonomy.16 In recent years, municipal autonomy has been strengthened, both through the inclusion of a provision in the Norwegian Constitution and through the new Local Government Act of 2018.17

The local government sector is responsible for many different tasks, including basic welfare services and local societal development. The municipalities’ duties have increased significantly in recent years. At the same time, the challenges facing society have become more complex, and increasing demands are made of the local government sector as a service provider and development agency.18 There is a constant need for development and innovation in municipal services, including core areas such as health and care services and schooling, and technical services such as water and wastewater management. Norwegian Water has estimated the investment costs for municipal water and wastewater facilities up until 2040 to be approx. NOK 280 billion.19

The municipalities are the most important planning authority, with responsibility for public and land use planning at the local level. All stakeholders in the local community should be involved in the preparation and implementation of the plans.20 Digitalisation will play a significant role in all service areas going forward.

Work on innovation in the local government sector

Municipalities and county authorities work on innovation in connection with service provision, the exercise of authority, societal development and as a democratic arena. There are differences within the sector in terms of which municipalities report innovation activities. According to KS’s Innovation Barometer for 2020, the most innovative municipalities are medium-sized or relatively big (a population of 20,000–50,000), centrally located, have a low proportion of ‘free’ revenues and large enterprises with many employees, and are more often situated in Eastern Norway than anywhere else in the country.21

Municipalities in rural areas have small populations and greater geographical distances. The capacity for innovation and new ways of working is weaker in small rural municipalities than in big, urban ones.22 Small rural municipalities can also find it difficult to recruit and retain sufficient competence to be able to develop and deliver services.

The Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS) is the organisation for all local authorities in Norway. All municipalities and county authorities are members. The organisation acts as a development partner for municipalities and county authorities, as a lobby organisation vis-à-vis the central authorities and as a party to negotiations with local government trade unions. KS has devised a number of educational instruments relating to innovation and it contributes actively to partnerships tasked with promoting innovation in the local government sector. In 2019, together with municipalities and county authorities, KS established a partnership for radical innovation. KS also administers several relevant digitalisation schemes, for example Digifin (Box 6.3).

Evaluations show that municipalities that have been merged are now better equipped to meet future challenges relating to service production and business and societal development.23 Larger expert communities also provide added assurance that the decisions made are the correct ones. The municipalities are now in a better position to ensure equal treatment and due process protection, especially in child welfare services, technical services and specialised health services.

The break-even analysis that was conducted in connection with the ongoing local government reform shows great variation between the municipalities in their performance of key tasks. A substantially higher proportion of small municipalities consider their own capacity to be poor.24 Small municipalities with a population of less than 3,000 do not have sufficient expertise to meet the need for more specialised services, either in their own organisation, via intermunicipal cooperation or through private suppliers.25

The municipalities engage in widespread collaboration, among other things in formalised intermunicipal partnerships or in networks, for example on digitalisation (Box 6.4).

Local government reform and innovation

Reforms and structural changes can provide a basis for both digitalisation and innovation. When municipalities merge, they need to agree, for example, on which systems, procedures and practices the new municipality will use. That allows room for new ways of thinking. At the same time, reform does not automatically lead to innovation. Reform processes can be challenging, and extra effort is often needed to achieve innovation in large reorganisation processes, while also retaining what works well. A number of the municipalities that have been or will be merged in the ongoing reform have innovation on their agenda for the merger process (see example in Box 3.3).

Textbox 3.3 Innovation in the new Øygarden municipality

From 1 January 2020, Fjell, Sund and Øygarden were merged to form Øygarden municipality. The municipalities have each had their own fragmented, differently organised services for vulnerable children and young people, and their next of kin. As part of the merger process, they wanted to develop a new comprehensive service for this vulnerable group.

Based on the service design method and process guidance, they set out to work together and develop the new service jointly.

The coordination of new municipal services for vulnerable children and young people in Øygarden is an example of how large-scale organisational changes, such as a merger of municipalities, can provide fertile ground for new ideas about how tasks can be carried out in the best interests of citizens.

Source Norwegian Digitalisation Agency

Regional social development by the county authorities

The county authorities’ role in regional social development is about setting the strategic direction for social development, mobilising the private sector, the cultural sector and local communities, and coordinating public contributions and the use of policy instruments.26 Social development thereby offers opportunities for promoting innovation in both the public and private sector, among other things through collaborations and public procurements. Box 11.5 shows an example of this.

3.2.3 Risk aversion and incentives

The public sector manages our shared resources and safeguards citizens’ rights. Errors in the public sector can have negative, and at worst, serious consequences.

Many municipalities point to the focus on operational matters as the greatest barrier to innovation.27 The desire to ensure efficient operations can reduce willingness to try something new. Risk aversion is also related to the political responsibility of public agencies, which are followed up through control mechanisms such as state supervision of the local government sector by the Office of the Auditor General.

Unlike private enterprises, public agencies are not at risk of being outcompeted if they fail to modernise. At the same time, the risk of not making changes can be greater in the long term, for example by becoming outdated and losing people’s trust.

Public sector innovation is one of the Government’s main strategies for addressing the challenges facing society and seizing opportunities in the years ahead. At the same time, innovation must not be at the expense of individual people’s rights, public exercise of authority or citizen’s due process protection and equal treatment. That would be negative for both the affected citizens and for trust in public authorities.

3.3 Innovation in a time of crisis

Crisis preparedness and response is about being able to deal effectively with a crisis and the challenges it brings, also when it is impossible to predict how the crisis will develop. Among other things, it is about having capacity and a culture of, and training in, innovation and swift change.

3.3.1 The COVID-19 pandemic

While work on this white paper is being completed, Norway and the world is in the midst of a crisis. The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, which causes the disease referred to as COVID-19, has led to a pandemic. Vulnerable groups, such as elderly people and people with underlying illnesses, are particularly hard hit. The authorities in Norway and many other countries have implemented extensive measures to reduce the spread of the infection and the burden on the health service. There is still considerable uncertainty associated with the new virus, and more knowledge and research is needed going forward.

COVID-19 and the stringent infection control measures have led to major changes in how people live, work and interact with others, also internationally. The situation is challenging because the authorities are required to make important and radical decisions based on information that changes by the hour. At the same time, challenges relating to Norway’s national security persist or grow. The situation requires innovation and new solutions at a time when traditional cooperation mechanisms are being challenged. The capacity to change seems to be in place even under changing circumstances.

Lessons learned from the pandemic have demonstrated a potential to accelerate digitalisation in many sectors, such as the health and care sector. The benefits will be there also after the pandemic has passed, and they will have more wide-reaching implications than just for crisis management. It is too early to say how the crisis will affect society and our surroundings in the long term and which solutions and changes will work in a normal situation.

3.3.2 Examples of innovation during the COVID-19 pandemic

Research

The EU has announced funding of EUR 164 million for the development of innovative solutions that can help to deal with the pandemic. The Research Council of Norway has announced an emergency call for proposals for collaborative and knowledge-building projects, and public-private innovation projects, to help the fight against COVID-19. The Trond Mohn Foundation and the Norwegian Cancer Society have also contributed substantial funds.28

Rapid sharing of research results helps to give countries the best possible foundation for evidence-based decisions. The Institute of Public Health (FHI) has an overview of scientific publications from all over the world, with detailed sub-groups that make it easy to locate relevant publications on specific topics. The overview shows where research is lacking, which can stimulate new, important studies. FHI collaborates with McMaster University, Canada.

Digital health service solutions

The use of video consultations with GPs has soared during the pandemic. In the week before 12 March 2020, when stringent infection control measures were implemented, the average number of daily video conversations between GPs and patients was 142. During the following weeks, an average of between 4,000 and 5,000 video conversations were conducted every day. Physiotherapists, psychologists and other health personnel have also made increasing use of video consultations during the pandemic.29

Joint solutions such as helsenorge.no offer quality-assured health information and the possibility of using administrative services to book appointments, renew prescriptions, request e-consultations and send messages to doctors. Several million people have used these services during the pandemic. Helsenorge.no has also played a decisive role in the introduction of new digital solutions for the health and care sector. The platform helps to overcome barriers to, and encourages more use of, digital solutions in patient care.

The health authorities receive input from many small and large contributors on digital solutions that can support work on the pandemic. All input is collated by the Directorate of eHealth and assessed in light of needs and challenges in the health and care services. The input is considered by working groups comprising representatives of the Institute of Public Health, the Directorate of Health and the Directorate of e-Health, or others where relevant. As of 8 April 2020, a total of 283 proposals had been received and 10 measures had already been introduced or implemented.

New digital tools introduced in a crisis or emergency response situation must be simple to use. In most cases, this means that the initiatives must be linked to existing solutions. Many of the good suggestions received will therefore be more relevant at a later date, when the crisis is no longer acute.

Infection tracing, and the possibility of contacting everyone an infected person has been in contact with, is an effective strategy for reducing the spread of infection. Many countries have developed digital tracing systems. At the same time as infection tracing plays an important role in limiting the pandemic, many of the systems are challenging in relation to privacy and personal data considerations. In Norway, the Institute of Public Health has launched the Smittestopp app, developed by the research institution Simula.

The national welfare technology program contributed to a joint procurement of electronic pill dispensers for 57 municipalities. The dispensers reduce the need for manual distribution of medication and thereby help to prevent infection, while also rationalising the work of health personnel.

The pandemic has also strengthened joint digitalisation efforts between the Institute of Public Health, the Directorate of Health, the regional health authorities, KS, the Directorate of eHealth and Norsk Helsenett SF. The same applies to cooperation with the supplier market.

Digital offices and teaching

Many people in Norway and the rest of the world are working from home during the crisis. Meetings are held by telephone and video, and conferences are digital to a much greater extent than before. The technology has been available for a long time, but the skills and extent of its use have increased considerably in a very short space of time.30 In addition, all schoolchildren have been remote schooled at home for a number of weeks. The situation has been challenging for pupils, teachers and parents alike, but it has contributed to a great deal of learning and sharing of experience between teachers on digital platforms.

Higher education courses are also taught digitally. The Faculty of Law at the University of Oslo was quick to establish digital teaching, and it conducted an evaluation after only a few weeks to find out how it was working. A resource bank for digital teaching was established, containing guidance for teachers on how to conduct lectures, courses and student supervision. In cooperation with colleagues at OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University, the Centre for Experiential Legal Learning (CELL) also set up a Facebook group for a digital initiative in higher education. It has served as a platform for sharing tips, advice and digital seminars on how to use digital teaching.

Collaboration with the business sector

Several countries are organising ‘hackathon’ events, where new solutions are discussed and developed in a short space of time. The organisation Design and Architecture Norway (DOGA) hosted a hackathon in Norway between 27 and 29 March 2020. The ideas were judged on the basis of their originality, feasibility and importance.31 The first prize went to the team Makers against COVID-19, which developed a face shield for healthcare workers that is easy to disinfect and can be used multiple times. The visor can be 3D-printed, and this job can be performed by a network of makers all over the country to ensure that health services have enough in stock. The solution thereby comprises both the visor itself and a production and distribution solution that can also be used for other products.

Over the course of a few days, the Norwegian Defence Materiel Agency (NDMA) helped to develop a solution for safe helicopter transport of COVID-19 patients. The Norwegian company EpiGuard has developed EpiShuttle, an isolation unit for the transport of infected patients, and teamwork with the search and rescue service and Kongsberg Aviation Maintenance Services, among others, meant that aircraft with isolation units could be taken into use in record time.32

Several private companies have developed new solutions in response to new needs in society. The sailmaker Gran Seil in Bærum has started making surgical gowns out of spinnaker fabric, and the Janus factory is developing a washable wool face mask.33

Private enterprises that already cooperate with the public sector to promote coordination and efficient use of resources have become more important. Nyby, Luado and Friskus are examples of matchmaking platforms that help to match needs with available resources, for example welfare tasks with available resource persons or activities in municipalities, voluntary activities, organisations and clubs and citizens.

Textbox 3.4 Compensation scheme for substantial loss of income as a result of the pandemic

In spring 2020, a large number of businesses experienced a sudden fall in turnover as a result of the pandemic and the infection control measures that were implemented. A temporary support scheme was introduced for enterprises experiencing a substantial fall in turnover, cf. Proposition No 70 to the Storting (Bill) (2019–2020). Through this scheme, enterprises can apply to the State for compensation for loss of turnover as a result of the pandemic and infection control measures. NOK 30 billion has been allocated for grants through the scheme, cf. Prop. No 127 to the Storting (2019–2020). The scheme is managed by the Norwegian Tax Administration.

It took just three weeks from the Tax Administration was given the task of preparing work on the technical solutions for the grant scheme until the scheme was open for applications. In these three weeks, the Tax Administration established new solutions for receiving and processing applications, and tools for production follow-up and case processing. Interfaces were also developed with the Tax Administration’s existing accounting and payment solutions, Altinn reporting solutions and an application and guidance portal that was developed in parallel by Finance Norway and DNB. Application processing and control is largely based on automated solutions with sophisticated rule and determination engines and artificial intelligence. Although a large number of Tax Administration staff have been involved in establishing the compensation scheme, the technical solutions were developed by a relatively small number of developers using agile development methodology. Technology and business development took place in parallel with the development of regulations to govern the scheme. This resulted in a very short time frame for the implementation of changes and testing of solutions. Parallel development of regulations and solutions and close dialogue between different Tax Administration disciplines helped to achieve short learning loops and the possibility of quickly making adaptations during the process.

The technical solutions on which the compensation scheme is based were the result of extraordinary efforts to resolve extraordinary challenges. And even though it would not be justifiable to organise the work in the same way under normal circumstances, work on the compensation scheme has resulted in both technology development and valuable lessons about efficient work methods and cooperation under great time pressure.

Source Ministry of Finance

3.3.3 Learning from crises

The instructions for work on civil protection and emergency preparedness require all ministries to evaluate incidents and hold drills, and ensure that the results and learning points are followed up.34 Translating findings from investigations into measures and change processes can be challenging. It is nonetheless important, also with respect to the possibilities for public sector innovation. Two examples of crises Norway has experienced in recent years are the terrorist attacks on 22 July 2011 and the unprecedented influx of asylum seekers in 2015.

The 22 July Commission, which was tasked with reviewing and assessing the public sector’s response to the attacks, concluded that there were shortcomings in emergency preparedness and that it was necessary to learn more from exercises/drills and follow through on plans. In the Commission’s opinion, the lessons learned concerned leadership, collaboration, culture and attitudes, rather than a lack of resources or a need for new legislation or organisation.35 This largely tallies with the drivers of innovation identified in this report.

An important lesson learned from the asylum crisis is that an innovative solution in one area, for example simplified on-site registration of refugees and asylum seekers, can be demanding in other parts of the asylum process. New solutions can be expedient in a crisis situation, but turn out to be less than optimal and have unintended consequences once the crisis has ended.

The Government believes it is important to learn from crises, and, in consultation with the Storting, it has appointed an independent commission to conduct a thorough, comprehensive review and evaluation of the authorities’ handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Footnotes

DeVries et al. (2016) Innovation in the Public Sector: A systematic review and future research agenda. Public Administration, volume 94, issue 1

In this report, public sector innovation is used as a general term. Public agencies can be entities at the central government, county or municipal level. The local government sector comprises municipalities and county authorities.

The definition is taken from the OECD’s Oslo Manual, and is used by the EU and OECD, among others. See OECD (2018): Oslo Manual 2018. Guidelines for Collecting, Reporting and Using Data on Innovation, 4th Edition

‘New, useful and utilised’ is also used as a definition in the public sector innovation barometers developed by KS and the Norwegian Digitalisation Agency, and in the reporting indicators health trusts use to gain a better overview of innovation activities.

In this report, the voluntary sector is used synonymously with civil society.

Report No 27 to the Storting (2015–2016) Digital agenda for Norway – ICT for a simpler everyday life and increased productivity

Regjeringen.no/kmd (Government.no/kmd)

Digitalisation Council (2019) Experience Report 2019

The Norwegian Digitalisation Agency consists of the former Agency for Public Management and eGovernment (Difi), Altinn and parts of the Brønnøysund Register Centre.

Report No 7 to the Storting (2019–2020) National Health and Hospital Plan 2020–2023

Kuhlman and Rip (2018) Next Generation Innovation Policy and Grand Challenges. Science and Public Policy 45 (4): 448–454

Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation (2019) One digital public sector. Digital strategy for the public sector 2019–2025

Halvorsen et al. (2005. On the differences between public and private sector innovation. Publin Report no D9

Difi (2018) Innovation Barometer for the central public sector 2018. Report KS (2020) Innovation Barometer 2020. The Innovation Barometers are innovation surveys conducted among central and local government agencies. In 2020, the local government sector barometer covered health and care services, children, young people and education services, the social sector, the technical sector and the culture sector. The survey in 2018 covered the health and care sector and children, young people and education services.

White paper on the central government administration, democracy and community. (Meld. St. 19 (2008–2009) Ei forvaltning for demokrati og fellesskap)

White paper on the local government reform (Meld. St. 14 (2014–2015) Kommunereformen – nye oppgaver til større kommuner (Reform of the municipality-structure – new tasks for larger municipalities)

Adopted by the Storting in spring 2016

White paper on regional policy (Meld. St. 5 (2018–2019) Levende lokalsamfunn for fremtiden – Distriktsmeldingen (Future Vibrant Communities

Rostad (2017) Finansieringsbehov i vannbransjen 2016–2040 (‘Need for funding in the water industry’ – in Norwegian only). Norwegian Water. Report 223/2017

White paper on regional policy (Meld. St. 5 (2018–2019) Levende lokalsamfunn for fremtiden –Distriktsmeldingen)

KS (2020) Innovation Barometer 2020

Telemarksforsking (2020) Små distriktskommuners deltakelse i innovasjonsvirkemidler (‘Small rural municipalities’ participation in innovation policy instruments’ – in Norwegian only). Report 540

Brandtzæg 2009 in Telemarksforsking (2020) Små distriktskommuners deltakelse i innovasjonsvirkemidler. (Small rural municipalities’ participation in innovation policy instruments’ – in Norwegian only.) Report 540

Borge et al. 2017 in Telemarksforsking (2020) Små distriktskommuners deltakelse i innovasjonsvirkemidler. (Small rural municipalities’ participation in innovation policy instruments’ – in Norwegian only.) Report 540

Brandtzæg et al. 2019 in Telemarksforsking (2020) Små distriktskommuners deltakelse i innovasjonsvirkemidler. (Small rural municipalities’ participation in innovation policy instruments’ – in Norwegian only.) Report 540

White paper on regional policy (Meld. St. 5 (2018–2019) Levende lokalsamfunn for fremtiden – Distriktsmeldingen)

Menon (2018) Nåtidsanalyse av innovasjonsaktivitet i kommunesektoren (‘Present-day analysis of innovation activities in the local government sector’ – in Norwegian only). Publication 88/2018. No corresponding survey has been carried out in the state sector.

Forskningsradet.no (The Research Council of Norway) and press release of 3 April 2020

The website ehelse.no reports that, in March, 33 per cent of all consultations were digital, compared to 3 per cent in January and February.

See, inter alia: nrk.no/kultur/korona-gir-boom-for-teknologien-1.14952712

Hackthecrisisnorway.com

Forsvaret.no

Teknisk ukeblad 17 March 2020, janus.no/munnbind

Instructions for the Ministries’ work with civil protection and emergency preparedness, issued on 1 September 2017.

NOU 2012: 14 Report from the 22 July Commission