5 Policy instruments for innovation

Figure 5.1

Each county authority, municipality and public agency is responsible for finding new and better ways of fulfilling its social mission, if possible in cooperation with others. In some cases, they may need support in the form of expertise, research or funding. Dedicated policy instruments have therefore been established for public sector innovation.

5.1 The current situation

5.1.1 Agencies and policy instruments for public sector innovation

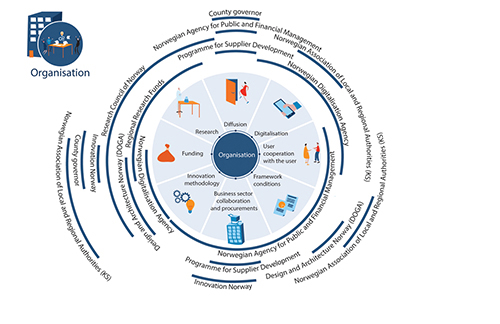

Several public agencies administer policy instruments and have special responsibility for ensuring that the public sector initiates, implements and achieves results through their innovation efforts. Figure 5.2 provides an overview of public agencies and policy instruments. KS has also developed a number of educational instruments relating to innovation and it contributes actively to partnerships tasked with promoting innovation in the local government sector (section 3.2). Several sectors have also developed their own innovation policy instruments, including the healthcare sector (Box 5.1).

The Government and ministries play an important role as drivers of innovation through their responsibility for policy formulation, goals, frameworks and policy instruments for innovation. Being a driving force for innovation entails setting goals, allowing freedom of action and providing incentives for innovation in subordinate agencies, and working to diffuse learning both within and between ministerial areas. The Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation is responsible for developing the central government and local government administration, including innovation and digitalisation in the public sector. The Government has also established a digitalisation committee chaired by the Prime Minister. The other committee members are the ministers responsible for particularly important digitalisation initiatives. The committee will be forward-looking and will organise the Government’s digitalisation efforts in a way that ensures good coordination and progress.

Innovation Norway is the central government and county authorities’ policy instrument for achieving profitable business development throughout the country. Innovation Norway also administers several policy instruments that involve joint participation by the private and public sectors. Innovation Norway aims to ensure that Norwegian businesses contribute to addressing major societal challenges. To achieve this, the instruments and schemes must strengthen public-private sector collaboration to ensure that the projects succeed in implementing and scaling up new technology. Innovation Norway does this through schemes such as innovation partnerships, innovation contracts and clusters (Chapter 11), in addition to the Pilot-T and Pilot-E schemes in cooperation with the Research Council of Norway. It awards innovation funding to stimulate business and industry and meet demand from the public sector, and the projects receive process guidance and can draw on the organisation’s expertise.

The main objective of Design and Architecture Norway (DOGA) is to use design-driven innovation to increase the competitiveness of business and industry and modernise the public sector. DOGA’s work includes developing educational tools for innovation, and it is a partner in the StimuLab scheme administered by the Norwegian Digitalisation Agency (Chapter 8).

The National Program for Supplier Development is an independent driving force that encourages more public organisations to use innovative procurements (Chapter 11). It is a partnership comprising over 30 municipalities, county authorities, central government agencies and research and education institutions. The Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, the Ministry of Health and Care Services, and the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries allocate funding to the program. Several of NHO and KS’s regional offices have regional contact persons. The steering committee for the program comprises representatives from NHO, KS, the Norwegian Agency for Public and Financial Management (the Norwegian Digitalisation Agency until autumn 2020), Innovation Norway and the Research Council of Norway.

The Regional Research Funds scheme was established in 2010. It provides funding for research and innovation projects using allocations from the Ministry of Education and Research. Several of the funds have prioritised funding research for and in the public sector, and they were among the first to fund this kind of project (Chapter 12).

The Research Council of Norway has overarching responsibility for ensuring that research communities can play a key role in developing a more knowledge-based and innovative public sector. The Research Council awards funding for, provides guidance about and creates arenas for research and innovation. Public sector innovation is an express priority area in the Research Council’s strategy for 2018–2023. The Research Council administers research and innovation funding in key areas of the public sector, such as health, education and welfare, transport and digitalisation, public sector PhDs and research-based innovation in the local government sector (Chapter 12). It issued the first call for proposals for pre-commercial procurement projects in 2019 (Chapter 11).

Figure 5.2 Overview of agencies and policy instruments

Overview of agencies that administer policy instruments for public sector innovation and the types of instruments available.

Source The Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation in cooperation with the Norwegian Digitalisation Agency, DOGA, Innovation Norway, the Norwegian Agency for Public and Financial Management, the Research Council, the National Program for Supplier Development and KS. Design: Halogen AS

The Norwegian Digitalisation Agency is the Government’s primary tool for digitalisation in the public sector. It contributes to achieving expedient digitalisation of society at large. The agency is also a driver of public sector innovation efforts, generating knowledge in the field, taking part in innovation collaborations and providing expert input for policy development relating to public sector innovation. Is also administers several instruments, including the Innovation Award, the stimulation scheme for innovation and service design (StimuLab) (Chapter 8) and the co-funding scheme for digitalisation projects (Chapter 13). The Norwegian Digitalisation Agency was established on 1 January 2020. It consists of the former Agency for Public Management and eGovernment (Difi), Altinn and parts of the Brønnøysund Register Centre.

The Norwegian Agency for Public and Financial Management (DFØ) is an expert body for governance, organisation and management in the central government. It is tasked with stimulating whole-system development in these areas. It has been assigned administrative responsibility for the Regulations on Financial Management in Central Government and the Instructions for Official Studies and Reports, and it provides joint services to the public administration relating to finances. DFØ is responsible for several policy instruments, such as competence-raising measures for employees and managers, and e-learning infrastructure in the state sector. In the second half of 2020, it was also assigned responsibility for public procurements, including innovative procurements. DFØ is thereby responsible for important framework conditions and policy instruments relating to public sector innovation.

The county governors are the central government’s representatives in the counties. They administer discretionary project funding for municipal innovation and renewal projects. The objective of the discretionary funding is to support the local government sector in testing new solutions and to stimulate local modernisation and innovation work.

Textbox 5.1 Policy instruments in the healthcare sector

National welfare technology program

Welfare technology can help the elderly to live at home for longer, and increase their quality of life and sense of security. It also has a large potential to improve the utilisation of resources in the care sector. Since its establishment in 2013, the Government’s investment in welfare technology through the National Welfare Technology Program has helped to increase innovation activity in municipal health and care services. The program is led by the Directorate of Health in cooperation with the Norwegian Directorate of eHealth, and KS. The goal of the program is to integrate welfare technology in health and care services in Norwegian municipalities. So far, the initiative covers more than 90 per cent of the population who live in municipalities that have participated in projects, for example the implementation of technology that increases security and independence, testing of medical distance follow-up and technology to help children and young people with disabilities. In 2020, the Ministry of Health and Care Services initiated a process to assess how the development and implementation of welfare technology could be best facilitated in the municipalities.

InnoMed

InnoMed is a national competence centre for needs-driven service innovation in the health and care sector. It was established by the Ministry of Health and Care Services. InnoMed stimulates increased activity, for example, by using health innovation tools. To link the competence service more closely to the services, responsibility for InnoMed was transferred to the regional health authorities in 2019 in cooperation with KS. InnoMed focuses on how challenges related to collaboration within and across service levels can be addressed. Efforts are also being made to scale up and expand InnoMed to include more competence areas, such as service design, law and innovative public procurements. This expansion will be based on the competence needs of the services.

EU, EEA and EFTA

The EU member states’ collaboration on innovation and development of the public sector is part of several policy areas. The EU has several policy instruments for public sector innovation that are also relevant to Norway. The EU Framework Program for Research and Innovation makes substantial investments in public sector innovation (Chapter 12). Digitalisation is also a focus area in which Norway works closely with the EU.

5.1.2 Status of the use of policy instruments for public sector innovation

In the Innovation Barometer survey for the local government sector, around 60 per cent state that they have only used funding from their own budget for innovation work. Furthermore, 16 per cent have used special grants or innovation funding from the municipality or county authority, while 15 per cent have used Norwegian public support schemes or grants.1 Correspondingly, in the state sector, around 11 per cent have utilised public support schemes or grants.2 All in all, most innovations are funded by financial means the organisations already have at their disposal. There is also great pressure on established policy instruments. When support and funding is announced through schemes such as StimuLab, FORKOMMUNE and Innovation Partnerships, far more good applications are received than funding is available for.

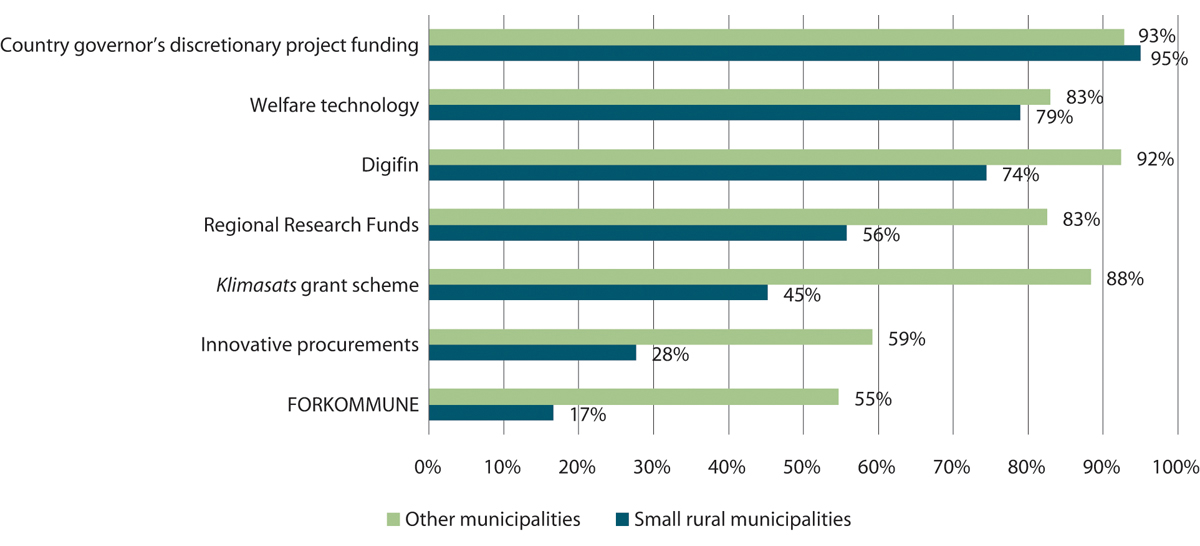

Large municipalities participate more often in central government innovation and digitalisation schemes than small municipalities. Among the small rural municipalities, most have participated in projects with support from the country governor’s discretionary project funding and the National Welfare Technology Program. The proportion of such municipalities with funding from the Regional Research Funds scheme is also significantly higher than for the Research Council’s program FORKOMMUNE (Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3 Share of municipalities that have participated in various schemes

Source Telemarksforsking (2020) Små distriktskommuners deltakelse i innovasjonsvirkemidler (‘Small rural municipalities’ participation in innovation policy instruments’ – in Norwegian only). Report 540.

Small municipalities are more dependent on collaboration to participate in large-scale innovation and development projects and are more often partners than principal applicants.3

5.1.3 The Nordic countries’ work on public sector innovation

On assignment for the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, the Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education (NIFU) and Rambøll Management Consulting have carried out a survey of the Nordic countries’ innovation policies.4 The following information about the Nordic countries is based on this survey.

Iceland: Integrated and flexible approach to public sector innovation

To stimulate challenge-driven innovation, Iceland has developed a policy-driven budgeting system since 2016, whereby budgets are grouped thematically rather than at the sector or ministerial level. Iceland has a strategy for innovation in the private and public sector (2019–2030) and is testing Innovation meet-ups, a scheme in which the private sector presents potential solutions to public sector problems or societal challenges. The Icelandic government has an Improvement Agency based at the Ministry of Finance, which helps public sector bodies to work better and more closely together, and a Future Committee chaired by the Prime Minister that gives advice about technology development, climate change and demographic changes.

Finland: Top-level support and experimentation

Since 2008, Finland has had a national innovation strategy for both the public and private sectors. Responsibility for innovation rests with the Prime Minister and the Office of the Prime Minister. Experimental Finland was one of the Prime Minister’s main projects during the period 2015–2019. Its goal was to foster experimentation in the public sector (Chapter 9). The program Design Finland aims to increase the country’s competitiveness and improve user experiences and efficiency in the public sector.

Sweden: A broad approach

The National Innovation Council, which is chaired by the Prime Minister, has an overarching program for work on facilitating innovation in Sweden across the public and private sectors. Sweden does not have one overall strategy for public sector innovation. In line with Norway’s approach, responsibility for innovation is divided between several central and local government agencies.

Vinnova has the clearest responsibility for innovation efforts in the public sector. It funds research and innovation initiatives, including testbeds and innovation platforms, and work on assignments, or missions, in the field of health-promoting and sustainable transport and food.

The Ministry of Finance has appointed a Delegation for Trust-Based Public Management whose remit is to discuss public agencies’ freedom of action to engage in innovation. The Government prepares a research and innovation proposition every four years.5 The Government has established a Committee for Technological Innovation and Ethics (KOMET), which is tasked with conducting analyses, mapping needs for regulatory adaptations and submitting policy development proposals to the Government.

Denmark: Innovation as a work method and systemic reforms

Denmark appears to be pursuing two main tracks in its public sector innovation work. One track involves introducing new tools and work methods in public bodies, while, in the other, political and top-down public reforms are introduced with the aim of modernising the Danish public administration. Denmark had a dedicated Minister for Public Sector Innovation under the Ministry of Finance during the period 2016–June 2019.

The National Centre for Public Sector Innovation (COI) was established in 2014. It receives funding from and is under the authority of the Government, Local Government Denmark (KL) and Danish Regions (DR).6 COI works to generate and diffuse knowledge about public sector innovation. It has developed common resources such as an innovation barometer, innovation awards, podcasts, example collections and guides.7 Denmark has also implemented initiatives such as the Coherence Reform (Sammenhængsreformen) and the free commune experiment. (Chapter 9).

A lot of research and innovation in Denmark is funded by private funds or foundations, such as the Carlsberg Foundation, the A.P. Møller Fund, the 15 June Fund and the Novo Nordic Fund.

5.1.4 Area review of business-oriented funding instruments

In 2019, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries and the Ministry of Finance conducted an area review of business-oriented funding instruments. The objective was to assess how funding channelled through the funding instruments can facilitate the highest possible value creation and profitable jobs. Policy instruments for public sector innovation have not been included in this review, but a number of agencies are part of both the business-oriented funding instrument system and public sector innovation system. Any changes resulting from the area review could therefore also be significant for public sector innovation. The review indicates that the policy instrument system works well, but that it is also complex. This is evident from the overlap between agencies and policy instruments, and interfaces that could be clearer.8 The external party behind the review recommends consolidation and simplification.

5.2 Assessment of the situation

Lack of a whole-system approach and difficult to navigate

There are a number of agencies and policy instruments in Norway tasked with supporting public agencies’ work on innovation. The policy instruments target funding, research, competence, innovative methods and collaboration between users and businesses, including innovative procurements. The instruments have been developed over time and in several organisations. This shows that innovation is an important topic for many actors. Reviews and evaluations show that the policy instruments and policy agencies achieve results and that the users value their expertise.9 However, the broad scope and diversity of instruments also gives rise to challenges. When preparing this white paper, the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation was in close dialogue with the policy agencies and users of the policy instruments. Based on this input, the Ministry’s view is that many of the policy instruments for public sector innovation target the early phases of the innovation process, while fewer instruments are available during the implementation phase. The National Program for Supplier Development has given feedback on similar experiences: that many of the policy instruments for innovative procurements target the early phase of the procurement process, while instruments for the development and implementation phases are lacking.

A number of public sector bodies have stated that they find it difficult and time-consuming to navigate the available policy instruments for public sector innovation.10 Nor is it straightforward to see how the instruments are interrelated and complement each other.

Policy instruments for individual projects and incremental innovation

Comparative studies show that Norway’s tools and support schemes are primarily tailored to the needs of individual organisations, and that we do not take a systemic approach to public sector innovation to the same extent as our Nordic neighbours.11 The OECD organisation Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (OPSI) has pointed out that Norway has low awareness of what kind of innovation the policy instruments are intended to stimulate.12 OPSI therefore recommends Norway to introduce a system-based portfolio approach to public sector innovation. This means an approach in which the policy instruments complement one another and foster several types of innovation, including incremental and radical innovation. It is difficult to achieve radical innovation, and OPSI therefore recommends actively prioritising policy instruments that can promote it. OPSI also recommends Norway to give one organisation responsibility for driving public sector innovation and promoting the portfolio approach.

Reasons for low participation in schemes by small municipalities

The research institute Telemarksforskning has looked at small rural municipalities’ participation in national policy instruments for innovation and digitalisation. In the survey, the municipalities point out that a municipality’s size, and thereby its expertise and capacity, limits its ability to participate in innovation and development projects.13 The professional environments are small, and fixed-term project manager positions can come to an end towards the end of the project period when new solutions are about to be implemented and the benefits realised. It is also a challenge that small municipalities have relatively few employees, who work as generalists with broad areas of responsibility. They therefore lack the capacity to keep abreast of national developments. Recruiting relevant expertise is also highlighted as a challenge.

The fact that small rural municipalities tend to a greater extent to participate in schemes adapted to regional challenges and needs indicates that how the schemes are designed may play a role in determining which municipalities make use of them. However, familiarity with the schemes and collaboration with larger municipalities also plays a role. The ministries will assess the measure in light of the findings from Telemarksforskning’s survey.

5.3 The way forward

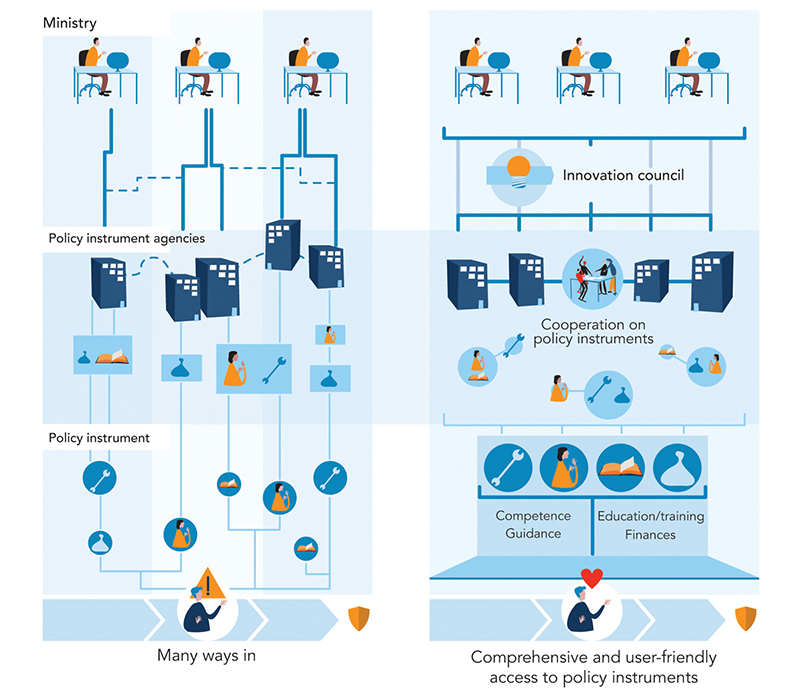

Norway has many expedient policy instruments for public sector innovation. However, the Government also believes that a more holistic-system and coordinated approach is needed with greater emphasis on the user perspective. This means that the policy instruments, both individually and together, will be adapted to users’ needs, and that they will be made available in a user-friendly way. The objective of the policy instruments is to help to find solutions to public sector and societal challenges, and ensure that the public sector grasps new opportunities. They also need to address small rural municipalities’ need for innovation and development. This will require policy instruments that take regional differences into account and ensure that innovations are diffused to municipalities with different points of departure. The changes require a clearer system and portfolio perspective, as regards both the policy instruments and the agencies that administer them. Figure 5.4 illustrates the desired situation with a whole-system approach and a user-oriented service.

This white paper is the first step towards establishing a cohesive national policy for public sector innovation. It is thereby a contribution to the work on developing a cohesive innovation system for the public sector.

5.3.1 Council for public sector innovation

The Government will establish a council for public sector innovation to ensure that, together, the policy agencies provide good comprehensive services to users and use resources in the most effective way possible. The council will consist of representatives of organisations that administer policy instruments for public sector innovation, and of municipalities and central government agencies that are part of the target group for the policy instruments. Since there are interfaces between policy instruments targeting the public sector and the private sector, it must be considered whether representatives of the agencies that administer the business-oriented funding instruments should also be included. The purpose of this collaboration would be to coordinate efforts in this area, ensure that measures and policy instruments support adopted policies, and create a common understanding of the knowledge and development needs in a long-term perspective. The council should endeavour to take account of all types of municipalities and entities in its assessment of the policy instruments. The innovation council can provide advice on the development of the Government’s policy for public sector innovation, and important policy areas for public sector innovation, such as the Long-term Plan for Research and Higher Education. The council will adopt a long-term perspective and facilitate continuous development of the ecosystem for public sector innovation. The Minister of Local Government and Modernisation is responsible for coordinating innovation policy in the public sector, and the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation is a driving force for development in this field. The Ministry will be responsible for appointing, developing and running the council. The council will be evaluated before a decision is made on whether to continue with it.

The Ministry also recognises the importance of informal and open collaboration between policy agencies, KS and representatives of the target group for policy instruments in the state sector and the municipalities. Through the work on the white paper, an informal network was established between the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, policy agencies and KS. The purpose of continued collaboration would be to strengthen the relationship between agencies and policy instruments, identify any blind spots and development needs, and to develop joint initiatives and projects. The Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation and the Norwegian Digitalisation Agency will take responsibility for further developing the network collaboration. Since this is an informal network, however, managing and developing the collaboration will be a collective responsibility.

The two collaboration forums must be seen in conjunction with and cooperate with each other, as well as with KS’s partnership for radical innovation. The partnership aims to develop and implement prioritised and necessary system innovations in important areas of society, such as social exclusion, future welfare systems and climate and the environment. The Strategic Council for Innovation and Research has been established as part of the program. It consists of senior executives from municipalities and county authorities with broad, strategic competence in innovation and research. The Council will carry out strategic assessments, decide priorities and choose the direction for the program, as well as discussing choices of innovation topics and the composition of the innovation portfolio.

5.3.2 Comprehensive and user-friendly access to policy instruments

Instruments that our target group do not know about are of little value. The Government will therefore endeavour to make policy instruments for public sector innovation available in a more comprehensive and user-friendly way. This work must be seen in conjunction with existing solutions and ongoing work. The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries is working on a digital portal for businesses that want to apply for research and innovation funding, and the Norwegian Agency for Public and Financial Management is working on a digital overview of central government grants for the voluntary sector.

Figure 5.4 A whole-system and user-oriented service

Illustration of envisaged situation with comprehensive and user-friendly development and access to instruments.

Design: Halogen AS

5.4 The Government’s aims

Policy instruments for public sector innovation must be adapted to user needs and contribute to more innovation, more radical innovations and the diffusion of successful innovations.

The Government will:

establish a council for public sector innovation comprising representatives from policy agencies, central government agencies and the local government sector

make policy instruments available in a comprehensive and user-friendly way.

Footnotes

KS (2020) Innovation Barometer 2020

Difi (2018) Innovation Barometer for the public sector 2018. Report

Telemarksforsking (2020) Små distriktskommuners deltakelse i innovasjonsvirkemidler (‘Small rural municipalities’ participation in innovation policy instruments’ – in Norwegian only). Report 540

Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education (NIFU) and Rambøll Management Consulting (2019): De nordiske landenes strategier for innovasjon i offentlig sektor (‘Public sector innovation strategies in the Nordic countries’ – in Norwegian only). Report

Equivalent to the Norwegian Long-term Plan for Research and Higher Education

KL is a special interest – and employer organisation for Danish municipalities, while Danish Regions has an equivalent role for the five Danish regions. KL and DR together are therefore equivalent to KS in Norway.

www.coi.dk

Deloitte (2019) Områdegjennomgang av det næringsrettede virkemiddelapparatet. Helhetlig anbefaling om innretning og organisering av det næringsrettede virkemiddelapparatet (‘Area review of business-oriented funding instruments. Overall recommendation on the approach to and organisation of the business-oriented funding instrument system’ – in Norwegian only). Report

Menon (2017) Midtveisevaluering av Nasjonalt program for leverandørutvikling (‘Midway evaluation of the National Program for Supplier Development’ – in Norwegian only). Publication 66/2017, Difi (2017) Innovasjon i offentleg sektor – både heilskap og mangfald ‘(Innovation in the public sector – both the totality and diversity’ – in Norwegian only). Report 2017:1

Difi (2017) Innovasjon i offentleg sektor – både heilskap og mangfald. ‘(Innovation in the public sector – both the totality and diversity’ – in Norwegian only). Report 2017:1

Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education (NIFU) and Rambøll Management Consulting (2019). De nordiske landenes strategier for innovasjon i offentlig sektor (‘Public sector innovation strategies in the Nordic countries’ – in Norwegian only). Report

OPSI (2019) Insights and Questions from OECD Missions to Inform the Norwegian White Paper on Public Sector Innovation. Report

Telemarksforsking (2020) Små distriktskommuners deltakelse i innovasjonsvirkemidler (‘Small rural municipalities’ participation in innovation policy instruments’ – in Norwegian only). Report 540