5 Regulatory developments and international frameworks

Photo: Vertigo3d

The prevalence of aviation is global, and the Norwegian authorities’ scope of action is to a great extent affected by global and regional guidelines and binding obligations. Norway has also largely adapted to regional and global guidelines and regulations. The UN’s International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the defence cooperation under the auspices of NATO and, not least, the EU, are especially important for the development of Norwegian airspace policy.

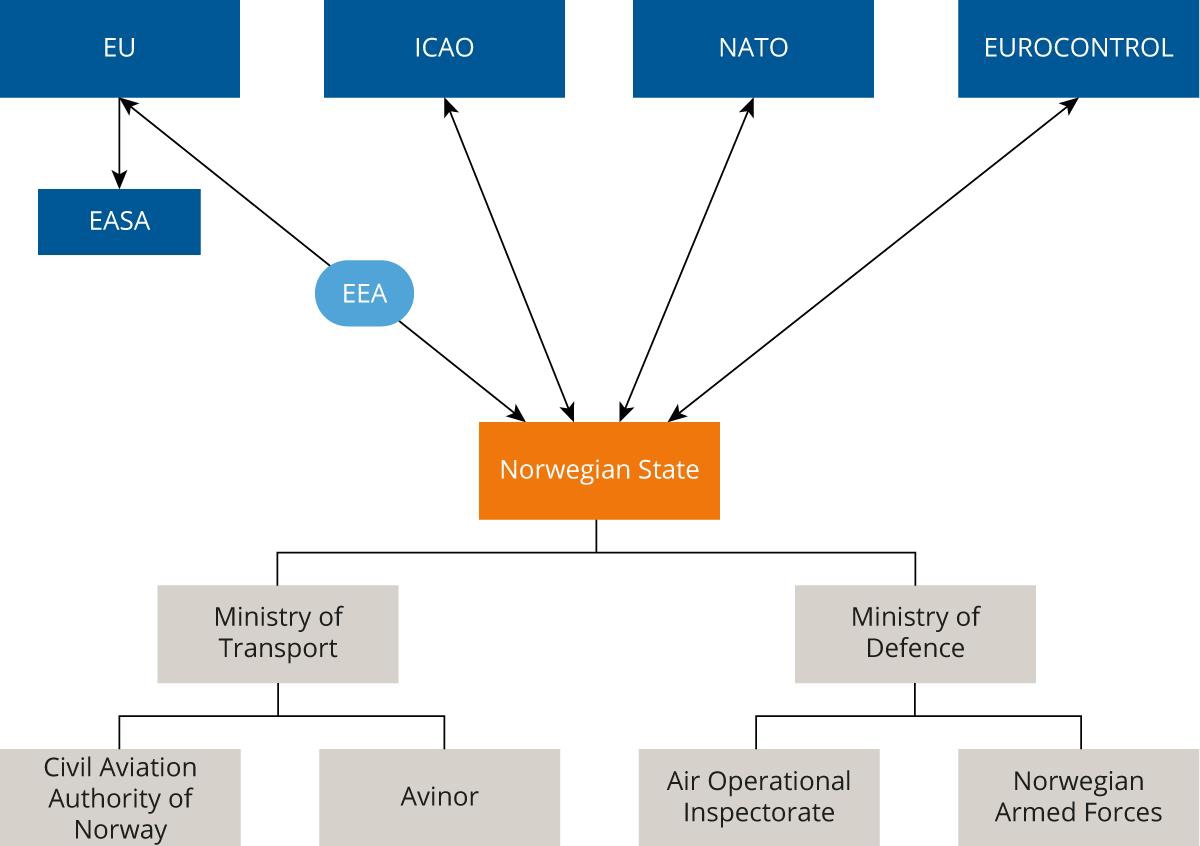

Figure 5.1 The figure illustrates the connection between global, regional and national government and administrative actors.

5.1 Global actor – The UN Specialized Agency ICAO

The Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation is an international treaty that determines the overarching rules governing international civil aviation, and which establishes the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). By having acceded to the Chicago Convention, Norway, as a state, has a number of rights and obligations under international law that also relate to the use of the airspace. Principally, the Convention establishes each state’s exclusive sovereignty over the airspace above the territory of the state, and the states are obliged to provide air navigation services of an adapted scope in their own territory.

Regarding the more detailed rules governing how the airspace in the individual state is to be organised, these are mainly set out at the global level in what are referred to as standards, recommendations and procedures, hereinafter referred to as the “ICAO rules”, which follow from annexes and other supporting documents to the Chicago Convention. Through the Convention, states parties undertake to observe the ICAO rules to the extent possible. Thus, states parties may refrain from fully observing the ICAO rules in their own territory but are then required to actively inform ICAO thereof.

It is first and foremost Annex 11 to the Convention regarding Air Traffic Services that is of direct relevance for how the airspace is organised. The Annex states the main rules for how the airspace is to be divided, based on the availability of air traffic services. The Annex and the Norwegian national Regulations relating to airspace organisation generally correspond. Norway has reported minor deviations to ICAO, relating to special Norwegian conditions that have made it necessary to establish a controlled airspace at a lower altitude than indicated by the ICAO rules.

Since the most important processes in the development of global aviation occur under the auspices of ICAO, Norway has to have an overview of ongoing processes, and seek to have direct influence in areas that are of particular importance for us. However, it is most appropriate to devote the majority of resources relating to international efforts to the European level. Through the EU system, we can especially influence common European positions in relation to ICAO. It is also important that Norway has a special focus on the processes in the EU, since these are largely converted into binding regulations for its member states. Such regulations will, in principle, also become binding for Norway as they fall under the scope of the EEA Agreement.

5.2 Trans-regional actor – NATO

Through NATO, Norway also undertakes to ratify STANAGs (Standardisation Agreements) and plans that first and foremost enable NATO operations in the Norwegian airspace and prepare transitions for a NATO takeover of the Norwegian airspace. The regulations affect the implementation of Norwegian assertion of sovereignty as the establishment of a recognised air picture and “Air Policing” of the Alliance’s airspace is an ongoing and continuous NATO-led operation.

Norway participates in relevant committees in NATO that develop frameworks and guidelines for military use of the airspace in the Alliance. Through this participation, Norway has the possibility to influence the development of plans and STANAGs.

Since several NATO counties are not part of the EU/EEA, the EU’s regulations will not necessarily be implemented in NATO. However, Norway is entirely dependent on being able to establish NATO-led operations in the Norwegian airspace as part of its security policy. Norwegian authorities will be challenged as to whether they are willing to transfer the exercising of public authority in the airspace to NATO if we are unable to fully support NATO operations.

5.3 Regional actor in Europe – the EU

Through the EEA Agreement, Norway is bound by all EU regulations in respect of airspace under international law, and there is also a strong presumption of continuous implementation of new legislation in the area (cf. the presumption of legislative and judicial homogeneity within the EEA). The trend in the EU is that the ICAO rules are directly implemented into EU law by way of separate legislative acts, with possible common European deviations. From 2022, certain ICAO-based principles for the organisation of the airspace will apply pursuant to EU legislation, including which factors are to be emphasised when determining the need for air traffic services in the individual parts of the airspace.

With the Single European Sky (SES) initiative, the EU shapes the administration of the European airspace. The objective of the SES regulations is, among other things, to contribute to safer, less expensive, more efficient and more environmentally friendly aviation in Europe, based on a more integrated and modern European aviation system that is capable of handling future growths in traffic.

The first SES regulatory package adopted by the EU in 2004 concerned, among other things, the establishment of National Supervisory Authorities (NSAs) to regulate the provision of monopoly services, the introduction of state certification of the national air traffic service providers and the introduction of Flexible Use of Airspace (FUA) to accommodate the needs of both civil and military aviation. In addition, the joint European ATM research programme, SESAR, was launched. In Norway, the NSA is the Civil Aviation Authority of Norway.

The first revision of the regulations (SES 2) was adopted in 2009. Rules were established for the Performance Scheme. The Performance Scheme is based on European contributions (performance plans) to common European targets for member states’ provision of air navigation services in the areas of safety, cost-efficiency, environment and capacity. In addition, a network manager function was established to complement and ensure optimal use of the common European network. Under SES 2, member states were also required to establish what is referred to as Functional Airspace Blocks (FAB), consisting of multiple states’ airspaces.

A further revision (SES 2 +) was proposed by the European Commission in 2013 but was never adopted by the Council and Parliament due to disagreements between member states.

5.4 The EU’s proposal for amendments to the SES regulations

In autumn 2020, the European Commission submitted a revised proposal; SES 2+. The Commission clearly states that it believes there is a need for further improvement of efficiency, especially relating to the use of the airspace. A strengthening of the network functions and the work of the network manager are considered important means of realising common targets. The European Commission emphasises opportunities for more extensive coordination and cooperation to achieve the most efficient traffic management possible throughout the network. The Commission also proposes to strengthen the possibilities for competitive tendering and privatisation of parts of air traffic services that have traditionally been provided as part of monopoly services.

A further growth in traffic in European aviation over the next 20 years challenges traditional solutions for safe and efficient traffic management. This is the background for the work and report prepared by SESAR Joint Undertaking: «”A proposal for the future architecture of the European Airspace/Airspace Architecture Study”7. At the same time, the European Commission received the report from a specially appointed group, “the Wise Persons Group”: «The future of the Single European Sky»8. The European Commission has given weight to these reports in the revision of its most recent legislative proposal: SES 2+: “A fresh look at the Single European Sky”9. Therein, it is stated, among other things, that larger and more structural changes need to be implemented in order for the European airspace to be able to accommodate future growths in traffic.

The tendency in European aviation until the spring of 2020, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, has been major capacity challenges where the current European aviation system has reached its capacity limit with existing operating models. This especially applies to central parts of Europe. Other characteristics of European aviation include that it is fragmented and inefficient with national special interests, pressure on cost levels and the emergence of new actors, such as drones, which are challenging the convention use of the airspace. The capacity challenges have been high on the agenda in the EU, and there has been discontent with the fact that the European suppliers of air navigation services have not sufficiently succeeded with efficiency improvement measures following the introduction of the SES regulations in 2004. There has also been discontent with the fact that the proposal from 2013 could not be adopted.

It is too early to assess the long-term effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on aviation. Eurocontrol expects that traffic will at the earliest return to 2019 levels in 2024.

The Commission wishes to implement targeted measures, including through strengthening the common European network to avoid congestion of air traffic, prevent sub-optimal flight routes, facilitate a market for common European data services, as well as innovative solutions that contribute to efficient and environmentally friendly European aviation.

The proposals in SES 2+ are currently under consideration by the Council and Parliament. The plan was that the Council would be done with its work before Christmas 2020, but negotiations and clarifications are now at the earliest expected in the second half of 2021, with entry into force first in 2024/2025.

It is important to identify whether there are aspects of the new proposal that affect special Norwegian interests in both a short-term and long-term perspective, and whether this indicates a more active and enterprising attitude on Norway’s part. To date, Norway has had a positive wait-and-see attitude to the consideration of the legislative proposals and the discussions that are now ongoing in the Council and Parliament.

The member states are holding continuous, in-depth discussions regarding the individual aspects of the proposal in the Working Party on Aviation and are thereby also clarifying their national positions. There are several challenging problems for which it appears difficult to garner sufficient support. As a non-EU member state, Norway has little possibility to influence this work.

Norwegian consideration of the proposals will be handled in accordance with established procedures, but it cannot be rules out that there may be problems that are of such a nature that they need to be elevated to a more overarching context and subject to more strategic assessment.

5.5 Possible consequences of the amendment proposals in the Singe European Sky regulations

Through the EEA Agreement, Norway has the possibility to influence the regulatory developments in the EU in terms of the best possible safeguarding of Norwegian interests, and structures have been established to ensure this. This possibility to influence, however, is greatest regarding rules that are adopted by the Commission, i.e., detailed implementation rules based on overarching framework regulations that are adopted by the Council and Parliament. In the drafting of overarching regulations that are adopted by the Council and Parliament, Norway has fewer possibilities to influence on its own because we are not formally represented in these institutions.

The SES2+ package that the European Commission formally relaunched in September 2020 is expected to be implemented in the EEA Agreement. Norwegian possibilities to influence up until adoption in the EU are limited. However, it may be important to identify significant aspects of the regulatory proposal and new amendments that are proposed by the Council and Parliament, so that clear Norwegian positions can be prepared and communicated in relevant channels in the EU system.

Norway is positive to the SES initiative and has implemented the legislation from 2004 and 2009, respectively, in addition to an extensive and detailed set of implementation rules with a legal basis therein. The amendments at the overarching level that are now being discussed will have major significance for the development and framework conditions for European aviation. This will result in a continued development with stronger coordination and control of civil air traffic service provision.

The current SES 2+ proposal involves strengthening existing mechanisms in order for decisions in the network functions to be followed up by all actors involved. An efficient handling of capacity challenges, in particular, presupposes the strengthening of such centralised solutions. For Norway and other European limitrophe states, these challenges are not as pressing. Similar to many other countries, it is important for Norway to ensure that measures are not implemented that will affect airspace users and authorities unnecessarily or entail more expensive requirements, which are primarily a result of Central European challenges. Norwegian authorities are continuing to assess whether it is appropriate to argue in favour of scalable and differentiated requirements to safeguard these concerns.

The performance and charging scheme of the air navigation services is strengthened in that the existing Performance Review Body (PRB) is embedded as a permanent structure under EASA, but nevertheless shielded and ensured independence and financial and professional autonomy from EASA, otherwise. The process for approval of national performance plans for the en route services will be direct and finally regulated by EASA as PRB, but these decisions may be appealed to a separate, dedicated appeal body – the Appeal Board for Performance Review.

It is natural to examine what effects the implementation of the EU’s initiatives will have for Avinor. In a longer time frame, the EU’s clear ambition is to digitalise, and to a greater extent automate the air traffic services in the European air space. This presupposes a coordinated roll out and implementation of new technologies, which, among other things, may open for more virtual air traffic service units that can provide services regardless of state affiliation. It opens the possibilities for more extensive provision of services across national boundaries.

The proposal to facilitate the opening of the market for exchange of common European data services, will also be assessed carefully. There is a desire for these and other support services for the air traffic services to be offered to a greater extent on competitive terms. On the one hand, this will be beneficial in terms of economies of scale and, presumably, cost savings. It may also entail access to new markets for Norwegian service providers, either independently or in alliances with others. However, there are certain concerns relating to whether a smaller Norwegian service provider like Avinor would be sufficiently competitive in such a market, or if European actors would take over responsibilities and duties that have traditionally be provided by the national service provider. Several of the largest Central European service providers have already positioned and established themselves in the market.

There is also a security policy dimension that will possibly require an acceptable solution relating to common data exchange, where it is proposed to make network data available for the entire European network.

5.6 Consequences of international developments in aviation for the Norwegian Armed Forces

The international development in regulations and administration of the airspace is largely driven by and for commercial aviation. For instance, the intention of SES is to improve the performance of the air navigation services relating to the civil application of the airspace by improving safety, reducing the environmental impact, increasing capacity and improving cost-effectiveness in civil aviation. Even though it is explicitly stated in the SES regulations that states’ sovereignty over their own airspace is not affected, and that the rules are also not applicable to military operations and military training10 (this is proposed continued in SES 2+11), the developments affect the operating environment for military air operations.

The developments in the areas of automation, data exchange and digitalisation are formalised in international regulations and challenge military aviation’s special needs and thereby its capabilities to solve the duties of the Norwegian Armed Forces. This becomes especially apparent when the Norwegian Armed Forces is to fly according to civil aviation rules and when the Norwegian Armed Forces assumes control of the airspace and has to safeguard the civil aviation rules. Generally, it is also a challenge that civil aviation and the Norwegian Armed Forces have traditionally used many of the same systems for surveillance and flight navigation, and changes to these functions on the civil side will affect the Norwegian Armed Forces.

Therefore, the Ministry of Defence has for several years focused on the development and drivers of the SES regulations and has through the development of a concept study outlined measures to face the challenge that the long-term ambition of SES represents.

Military aviation must have effective and secure access to all types of airspace to train, conduct exercises and to execute missions within national and allied frameworks in times of peace, crisis and war. The concept study addresses, among other things, challenges relating to digitalisation, automation and the development of the network functions that are established in SES. Viewed in context with the military aviation technological and performance developments, as well as the deteriorating security policy situation in our surrounding areas, the concept study recommends the creation of a limited military air navigation service. It is especially the need for rapid transition from daily operations to crises that make such an establishment relevant. In practice, this service can be included as a specified provision by Avinor Air Navigation Services AS with requirements established by the Norwegian Armed Forces and which is under military aviation command on a day-to-day basis. Such an arrangement will fall within Avinor’s obligations through the designation decision. The concept study has been subject to external quality assurance according to the instructions of the Ministry of Finance. The external quality assurance supports the recommendation of a service with established military requirements and an emphasis on integrated civil-military cooperation. In the evaluation, the investment costs for all measures that are not platform specific for the Norwegian Armed Forces are estimated at approximately NOK 2.5bn. The conclusions from this work have formed the basis for the work on a Norwegian Airspace Strategy in order to provide an overall civil-military presentation.

Norway is one of few countries in Europe that currently does not have a military air navigation service, and the Norwegian Armed Forces therefore does not have competence within its own organisation to safeguard own air navigation, considering that the services are to be provided by a civil air traffic service provider. Given the developments, it appears that Norway, in a Total Defence context, is best served by, in addition to the already established civil-regulated air navigation services, also establishing a certification system, regulated by the Military Aviation Authority (MAA), which, overall, safeguards ICAO’s, the EU’s and NATO’s requirements. This includes air traffic services (ATS), communication, navigation and surveillance services (CNS), aeronautical information services (AIS), meteorological services (MET) and search and rescue services (SAR). This will contribute to achieving robust and seamless transitions in the administration of the airspace throughout the conflict scale, which is currently not the case. NATO’s requirements for military air navigation services are specified and are in principle a number of additional requirements to ICAO and the EU, where the civil requirements for certification of controllers and organisation are prerequisites.

The concept study also assesses other challenges that the Norwegian Armed Forces has to solve when the operating environment in the airspace changes:

Recognised air picture: The operating environment has developed to utilise “cooperative” systems for air navigation, – which entails that all aircraft have to be capable of sending identification data to all airspace users. In order to assert sovereignty and control of the airspace, it is a prerequisite to also have the capability to detect “non-cooperative targets”, e.g., aircraft that fail to disclose their identity, purpose and position. Currently, we depend on a nationwide network of primary radars to achieve this – the Norwegian Armed Forces is alone in safeguarding this service based on requirements set by NATO, and the state will require increased sensor capabilities in order to compensate for the loss of primary radars.

Information security and cyber security: Air operations are entirely dependent on rapid and secure information exchange of digital data between all relevant actors and operators. SES entails major changes in terms of digitalisation and automation, and this affects the vulnerability of the system. The National Security Authority (NSA) currently does not allow the Norwegian Armed Forces’ command, control and information system (K2IS) to connect to civil ATM computer systems. Military aviation must have the capability to protect mission-critical information and compromising of information is not acceptable. Sharing of information with unclassified systems will therefore be a challenge. The centralised networks and services that are established in connection with SES are not as robust as the classified and secure networks that are used in connection with military air operations. Military systems must have sufficient protection and redundancy in order to ensure continued operations following possible outages or compromising of civil computer networks, GPS signals etc.

Interoperability: The Norwegian Armed Forces will address the interoperability dimension relating to materiel and procedures by being as “civil as possible and as military as necessary”, though there is a need for adaptations. Military aircraft must have multiple systems/equipment onboard to satisfy both the civil and military requirements in order to be able to operate seamlessly in larger military formations (national and allied forces) in airspaces with civil traffic. It appears from the concept study regarding the Norwegian Armed Forces’ adaptation to the SES regulations that materiel projects to adapt military aircraft and other military aviation components in relation to full implementation of the SES ambition will significantly increase the costs of military aviation.

5.7 The Norwegian Aviation Act

The EEA regulations in respect of aviation are implemented in Norwegian law in accordance with the Aviation Act of 11 June 1993. Section 1-1 of the Aviation Act determines that “Aviation in the realm may only be undertaken in accordance with this Act andregulations laid down under the provisions of this Act.” The Aviation Act consists of two parts – the first part regarding civil aviation and the second part regarding military aviation and other state flights for public purposes. Civil aviation is administered overall by the Ministry of Transport and, in practice, largely by the Civil Aviation Authority of Norway by way of delegation of authority. Subordinate regulations to the Aviation Act are issued in the form of regulations. Part II of the Act contains a chapter regarding military aviation and these rules are administered by the Ministry of Defence, which has designated the Chief of Defence (CoD) as Military Aviation Authority (MAA). The CoD has further delegated MAA to the Chief of the Norwegian Air Force. The MAA currently does not have regulated military aviation pursuant to regulations.

Section 9-1 of the Aviation Act states that the Ministry shall issue regulations about what precautions must be observed inorder to avoid collisions between aircraft or other air accidents and otherwise inorder to ensure safety against hazards and inconveniences, including noisepollution resulting from aviation activities. Otherwise, Chapter 9 contains provisions concerning, among other things, restricted areas and flight paths. Section 16-1 of the Aviation Act contains an authorisation concerning the implementation of the EEA Agreement in respect of civil aviation. This also applies to acts concerning the use of the airspace, such as acts relating to SES. Decisions implemented in accordance with Section 16-1 of the Aviation Act take precedence over the other provisions in the Aviation Act.

It is the Civil Aviation Authority of Norway as civil aviation authority that determines how the airspace shall be adapted. In principle, there are no parts of the airspace that are exclusively subject to military authority. However, the military can determine restrictions in the airspace in case of acute or unresolved military situations, including war and war-like and similar states of emergency (Section 9-1 a, second paragraph of the Aviation Act). Beyond this, we have an arrangement regarding flexible use of the airspace, especially directed at the Norwegian Armed Forces’ need for reserving parts of the airspace for military training. This arrangement is regulated under the Regulations of 13 March 2007 relating to flexible use of the airspace, which implements Regulation (EU) 2150/2005, Flexible Use of Airspace (FUA Regulation) in Norwegian law. The Regulations establish the various national Norwegian schemes for strategic, practical and tactical governance with regard to a flexible use of the airspace and constitute a civil-military committee comprised of representatives from the Civil Aviation Authority of Norway and the Norwegian Armed Forces, which is tasked with administering the scheme at the overarching level. Put simply, the scheme entails that the Norwegian Armed Forces can book predefined airspace blocks on short notice for training purposes. This airspace is then, in principle, reserved for the exclusive use of the Norwegian Armed Forces for the period this is needed. The strategic part of FUA involves a review of needs and possible adaptations of the predefined airspace areas, in scope and time.

In Part II of the Aviation Act, Chapter XVII concerns military aviation. Section 17-6 of the Chapter specifies provisions in the civil part of the Aviation Act that also apply to military aviation. In Section 17-7 it is stated that the same applies for regulations issued under certain provisions of Part I of the Aviation Act, unless the King (Norwegian Government) decides otherwise. Pursuant to Section 17-8, the King may also determine that other provisions of Part I of the Aviation Act apply to a corresponding extent to military aviation. Military aviation is administered by the Ministry of Defence and further regulated pursuant to the Regulations of 13 February 2015 no. 123 Relating to military aviation and the Provisions for Military Aviation (BML), which are internal instructions issued by the Military Aviation Authority.

The legal basis for the administration of the airspace must be clear and updated. New users have emerged and the traditional users are undergoing a transition, which will entail a need for innovative thinking. The regulations have to be sufficiently flexible and robust.

5.8 Strategy

The Norwegian Government will:

- Safeguard Norwegian civil and military legitimate interests in the implementation of the EU’s new initiatives under Single European Sky, including by ensuring the safeguarding of the Norwegian Constitution’s provisions regarding relinquishment of authority.

- Review how our obligations in relation to NATO are made legally binding in Norway.

- Further develop the cooperation regarding shared use of airspace across national boundaries based on the NORDEFCO model, in order to meet the needs of the Norwegian Armed Forces and other government agencies.

- Assess the need for a revision of the aviation legislation’s provisions regarding use and administration of the airspace.