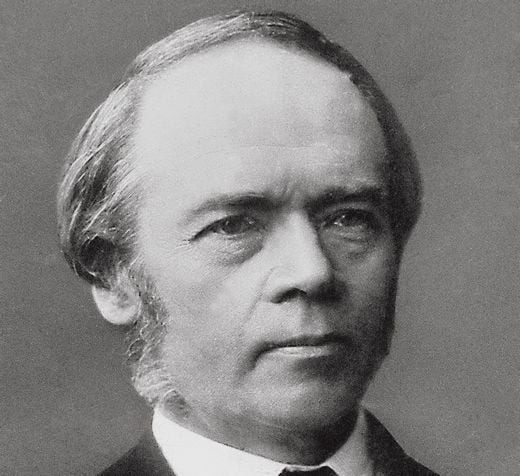

Ole Richter

Norwegian Prime Minister in Stockholm 1884 - 1888

Article | Last updated: 10/04/2012

Ole Jørgensen Richter was lawyer, civil servant and politician.

(Photo: Kunnskapsforlaget).

Norwegian Prime Minister in Stockholm 26 June 1884-6 June 1888.

Born at Rostad in Inderøy, County of Nordre Trondhjem 23 May 1829, son of farmer Jørgen Richter (1790-1880) and Massi Rostad (1798-1877).

Married in London 1866 to Charlotte Wakeford Attree (1830-1885).

Deceased in Stockholm 15 June 1888. Buried at Rostad in Inderøy.

Ole Richter was born at his mother’s family’s farm Rostad, which had been taken over by his father. He soon chose book learning, and after a stay with his uncle in Sjælland in Denmark 1847-1849, he returned to Norway for university qualifying examination and started law studies. He had his law degree from the University of Christiania (Oslo) after just two years of study, and was then acting district stipendiary magistrate of Stjør- and Verdal 1853-1855.

Richter’s main interest, however, was politics. Inspired by liberal and national movements he had met during his stay in Denmark, he had as his aim to form a Norwegian liberal opposition. He saw the existing opposition against the conservative government as being reactionary. As for foreign policy he wanted Norway to join the Western powers against Russia. He also underlined Norwegian independence in a situation where Sweden planned to increase its dominance in the union with Norway.

After studies in England and France 1855-1856, Richter returned home intending to enter political life. It was decisive that he became co-editor of the Christiania daily Aftenbladet. The newspaper now developed both a national and a European character, becoming a main channel for liberal politics and reaching the level of importance of Morgenbladet. One important issue for Richter was the introduction of the jury system in Norwegian courts, and in 1857 the Jury Act was passed by the Storting.

In addition to his newspaper activities Richter to a certain extent also worked as a lawyer in Christiania. Following studies in Switzerland in 1860, he earned his authorisation as a barrister. In 1861 he moved home to Rostad, started his own legal practice and entered local politics. His aim was to be elected to the Storting, and in 1862 he was elected representative of the County of Nordre Trondhjem. He was later re-elected in 1865, 1868, 1870 and 1873.

At the Storting Richter joined the group called the "lawyers’ party", where other leaders were later prime ministers Johan Sverdrup and Johannes Steen. Richter would often refer to England as a model of liberal politics. He spent much time on constitutional issues, among other items on government members’ access to the Storting’s meetings. Here he followed a less radical line than Sverdrup, regarding the issue primarily as a matter of practical routines – not a matter of the parliamentary system known from other countries.

However, as for politics concerning the union with Sweden Richter followed the same line as Sverdrup. This was also the case when it came to the importance of the constitutional role of the Storting. Still, the two came to drift apart politically. In 1876 there was an attempt to appoint Richter to the post as Swedish-Norwegian ambassador to Washington DC. When this did not succeed, Richter was appointed stipendiary magistrate in Trondhjem the same year, and moved there. He was re-elected to the Storting, but felt more isolated than before in the political debate. In 1878 he applied for the post as Swedish-Norwegian consul-general in London. The Norwegian Government nominated him and he was appointed, despite press claims that the appointment was a political reward.

Richter was already now referred to by Swedish press as a possible Norwegian prime minister in Stockholm, as he was seen to be able to reconcile political opponents. In this capacity he re-emerged in Norwegian politics in 1884. He was wanted as a government member when Professor Ole Jacob Broch attempted to form a new government in May 1884, and when this did not succeed King Oscar II wanted Richter as prime minister. This was not accepted by Sverdrup. Neither Richter himself wanted this, and he convinced the King that Sverdrup should be prime minister. Thus, Richter was appointed Norwegian Prime Minister in Stockholm when Sverdrup’s Government took over in Kristiania in late June 1884.

Richter was looking forward to serving as Norwegian prime minister in Stockholm, convinced that he had the right qualifications. Others found him to be assumedly distinguished. Richter was also looking forward to cooperating with Sverdrup, but was soon disappointed at what he saw as a lack of warm-heartedness on Sverdrup’s side. After a few months in office he had to face the painful loss of his wife in February 1885. One could now see an increase in the tenderness and nervousness that had been a part of Richter’s character since his youth.

Richter quickly came at edge with Sverdrup in several matters. Already in early July 1884, on the first day the new Government met the Storting, he expressed his disagreement with Sverdrup’s defence for an extension of the right to vote. On a proposal for a new organisation of the Army, Richter supported the minister who lost and had to resign, Minister of the Army Ludvig Daae.

After less than a year Richter had become so depressed over the situation that he began speaking of resigning, and in mid July 1885 he tendered his resignation. His plan was to return to the post as consul-general in London, which was still kept vacant for him. In order not to weaken the Government in the upcoming election campaign, he accepted to remain in office until after the general elections in the autumn of 1885. After being forced to make up his mind, also due to the wish to fill the post in London, and after having felt his health to improve, Richter chose to withdraw his resignation in mid-November 1885.

Autumn and winter 1885-1886 was marked by problems of reaching a Swedish-Norwegian agreement on the wording of the common union law – the Act of the Realm (Riksakten). Richter and the two Norwegian ministers at the Council of State Division in Stockholm were criticised by the Storting for having accepted a Swedish proposal on a new way of treating diplomatic matters. Richter was particularly offended by Sverdrup’s statement that he – Sverdrup - had not been aware of the wording of the protocol in which Richter accepted the Swedish proposal.

1887 saw the Sverdrup Government’s defeat in the Storting on the issue of Church of Norway parish councils, where the dissent of Richter and three other ministers threatened to overthrow the Government. Richter contributed to avoid a government crisis, but was disappointed that Sverdrup chose to replace the outgoing ministers with people Richter did not find suitable. Richter now grew increasingly worried at the way the liberal press kept attacking the Government, and was also increasingly at edge with Sverdrup in various matters. Again he spoke of tendering his resignation, also to Crown Prince Gustaf.

In a speech on Constitution Day – 17 May - 1888 author Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson delivered a powerful attack on Sverdrup, saying that the Government now did not have even the support of its own. It was now widely assumed that this was an assessment Bjørnson had got from his old friend Richter, during a recent visit to Stockholm. When Bjørnson shortly after referred to a letter from Richter in 1886, on the decision the Act of the Realm, Sverdrup stated that he and Richter could no longer continue in government together. In late May 1888 Richter was told by the Crown Prince to tender his resignation.

Richter now felt helplessly compromised, calling this treatment an ”assassination” and attempting to take his own life. Although he now found the draft of his letter to Bjørnson, and could see that Bjørnson’s rendering was incorrect, he waited to send this to Sverdrup – to avoid the impression that he sought to remain in the Government. In early June the recommendation for his resignation arrived from Kristiania, and on 6 June it was passed in an extraordinary Council of State session in Stockholm.

Richter, who continued to live in the Norwegian Prime Minister's residence (Ministerhotellet) in Stockholm, spent his time writing a report and to a certain extent on planning his future. But press comments continued to depress him, both with regard to his reputation in the Government and his possibilities of becoming the next Swedish-Norwegian ambassador to London. It was probably not until the early hours of 15 June 1888 that he came to see the newspaper Nya Dagligt Allehanda’s claim that Bjørnson had disqualified him and that he lacked an independent character, discretion and discipline. That same morning Richter took his own life with a revolver shot, in the Norwegian Prime Minister’s office in Stockholm.

Richter’s suicide triggered a debate on who should bear the blame. The conclusion was that the blame probably was evenly distributed. In his play Paul Lange and Tora Parsberg Bjørnson ten years later erected at beautiful monument to Prime Minister Ole Richter.

Source:

Norsk Biografisk Leksikon