1 Vision and values

1.1 Norway and the United Nations

The UN’s main task is to maintain international peace and security. The fundamental democratic values set out in the UN Charter are also those on which Norwegian society is based. Ever since the Organisation was founded in 1945, active UN engagement has been one of the main features of Norway’s foreign policy. Membership of the UN has been vital for the promotion of Norwegian interests and values, and our UN engagement has been strongly supported across different governments, in the Storting (the Norwegian parliament) and among the Norwegian people.

Norway's support for the UN is about interests as well as values. In the Government’s view an interest-based foreign policy is one that systematically advances the welfare and security of Norwegian society and promotes our fundamental political values. Our foreign and development policy is therefore based on respect for international law and universal human rights, and promotion of the international legal order.

International law and justice are crucial for our ability to promote and safeguard our interests. The UN enjoys a unique legitimacy because every member state has a voice. The Organisation is the only global body that can legitimise the use of force and is the most important arena for seeking intergovernmental solutions to threats against peace and security. The participation of Norwegian shipping in world trade would not have been possible without international rules. Smallpox could not have been eradicated in Norway without international cooperation in the health field. Respect for the Law of the Sea ensures predictability and stability, which is vital for Norway, especially in the High North – the Government’s most important strategic foreign policy priority.

In an increasingly interwoven world, as cross-border relations become closer and new global challenges arise, it is important to ensure that international rules and regulation are further developed.

Today, no country or organisation can equal the UN as a global arena for developing the international legal order and the norms governing relations between states. It is in Norway’s interest to support a world order in which the use of force is regulated. It is also in our interest that all states respect international law and have access to arenas where they can meet to agree on common solutions and address disagreements.

The global threats we are facing can only be dealt with if states join together in taking responsibility for them. In our globalised world, where national borders are no protection from disease and epidemics, terrorism, hunger, lack of clean water, poverty, climate change or growing environmental problems, it is in our interest to deal with these and other challenges at the international level. Foreign policy interests are increasingly linked with national policy development.

Norway has considerable room for manoeuvre in the UN. We are perceived as a credible and constructive supporter of the Organisation and as a major financial contributor, especially in the development and humanitarian fields. Norway’s experience with multilateral forums has shown that a long-term strategy and the ability to build alliances and think along new lines are essential, regardless of how we work and who we work with.

1.1.1 Norway’s UN policy in a changing world

The international legal order and the UN’s global role cannot be taken for granted. Geopolitical changes, fresh challenges and lack of political and financial stability impose new demands on international cooperation and on the UN’s ability to adapt and take on new tasks.

Today’s challenges are more complex than those of 1945, when the UN was founded. Adressing them requires an enhanced ability to deal with complexity and to link agendas with responses. Another problem is that some countries perceive existing international organisations as mechanisms for maintaining and intensifying the influence of the traditional major powers. The global shifts in the balance of power are not yet reflected in formal structures. The UN is also facing greater competition. The influence of new, informal groups like the G20, regional organisations, civil society and also private actors is becoming increasingly evident in the international arena.

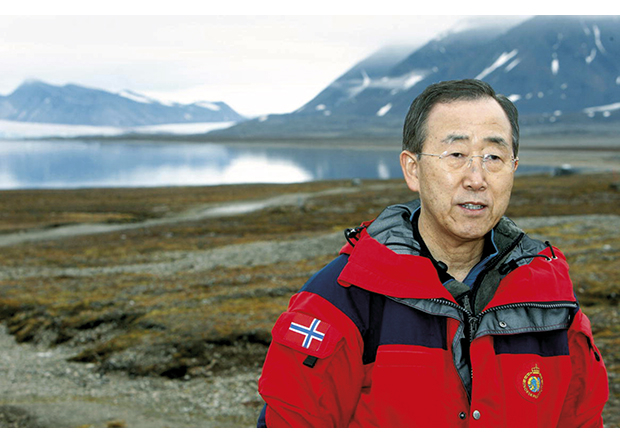

Figure 1.1 Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon visits Ny-Ålesund, 2009.

Source Photo: UN Photo/Mark Garten

Norway has also changed. We therefore need to review the priorities for our UN engagement and examine what we can do to strengthen the UN as a framework for a multilateral world order based on international law. Norway is one of 193 member states of the UN. We have 5 million inhabitants; the world population is 7 billion. However, our well-defined policy, long-term perspective, credibility and generous contributions have enabled us to exercise a strong influence relative to the size of our population. Multilateral efforts are taking up greater resources as the landscape becomes increasingly complex. This means that we must give some issues priority over others and focus on areas where we can make a difference. At the same time, we have found the breadth of our engagement to be an advantage, both for our reputation in multilateral forums and for identifying and exploiting opportunities to act when necessary.

Our predictable, long-term policy in key areas promotes our positive image. In a time when power is shared between a number of different actors, making conflicts of interest more likely, it is crucial to maintain clear positions and priorities if we are to address a larger number of agendas and find alliance partners that will support our priorities. We must prepare for new situations by defining strategies and identifying potential supporters in advance, so that we can take advantage of opportunities when they arise.

1.1.2 A well-equipped toolbox: the UN’s many roles and functions

The UN is an organisation of sovereign states. Every part of the UN system is governed by member states, which decide on mandates, programmes and budgets, and finance the Organisation’s activities. Through their membership, the states have committed themselves to the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and consequently to certain rules of conduct.

The UN has three main functions: It has a normative function, creating the norms and rules that make up the international legal order. It has a political function, being the arena where virtually all types of issues may be put on the agenda. It has an operational function, performing tasks in accordance with mandates from the member states.

Normative function: Most of the conventions and other legislation that make up the international legal order originated in the UN. Today the network of instruments of international law, declarations and global standards establish the basic rules of conduct for relations between states, which define the obligations of member states towards their own people and other countries. A number of mechanisms have been set up to monitor states’ implementation of these obligations. This normative function also gives several of the UN organisations and entities an important role as advocates.

UN norms and principles derive their significance from the fact that they are discussed and negotiated with all the member states around the table and adopted by consensus or a two-thirds majority. However, this also means that negotiating processes can be extremely difficult. It took 10 years to negotiate the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, but in the end it was adopted by consensus. This gives the Declaration great legitimacy.

Political arena: The UN is the only organisation with universal membership, where the members can raise virtually all types of issues. This gives the Organisation an authority and a representativeness that are unique in the world today. Every member state has a voice in the General Assembly, regardless of its size and political and economic power. The UN is perceived by many small and medium-sized states as being democratic and providing legitimacy, whereas larger states may find it unreasonable that their vote has no more weight than that of a small island state. Summits, the General Assembly and other general conferences set the agenda on vital global issues. Most importantly, the UN is an arena where sovereign states, but also civil society, the academic community, indigenous peoples and other interest groups, meet to negotiate and influence decisions. Norwegian NGOs and research communities are active in the UN and participate in several forums, either independently or as part of official delegations.

Figure 1.2 Palais des Nations, Geneva. The Afghan Minister of Labour speaking at the ILO Labour Conference.

Source Photo: United Nations Association of Norway/Hasse Berntsen

Operational function: The UN system performs tasks on behalf of the member states, for example in the management of global crises such as armed conflicts, humanitarian crises and epidemics. This requires standby systems and active crisis prevention efforts. These development and humanitarian efforts are the UN’s operational activities. The specialised agencies and UN funds and programmes provide expert advice, undertake capacity- and institution-building, and deliver services. Many of these bodies also perform tasks in basic social sectors such as health and education.

Figure 1.3 Maban County, South Sudan, July 2012.

Source Photo: Jake Dinneen

The growing need to address new and existing challenges has led to a corresponding expansion of the UN system. Norway has actively supported the establishment of many new institutions, but considers it an important principle that new entities should replace existing ones rather than adding to the number of institutions. A good example is the establishment of UN Women, which replaced four different entities. However, it has proved difficult to close down or merge organisations that particular member states helped to establish and for which they consequently have a strong feeling of ownership.

The growth in the number of institutions has resulted in a large and fragmented system with considerable coordination problems. The Government considers this to be one of the main challenges facing the UN today, and we are giving it high priority in our work for reform.

The financial crisis has put pressure on the funding of multilateral activities. Tighter budgets have resulted in demands for better documentation of development aid results and a stronger focus on getting value for money. Norway is working together with other donors to improve the capacity of UN organisations to document their results and show that they have used the funds effectively. Norway intends to maintain a high level of financial contributions to organisations that deliver, and to penalise those that do not. We will also mobilise new donors.

1.1.3 The shifting balance of power – consequences for the UN as an arena for negotiation

It has been said that when the Cold War ended, the world experienced a unipolar moment. Only 20 years later, the global landscape has become far more complex. A number of countries have experienced rapid economic growth, especially China, but also India and Brazil. So far the various countries’ increase in economic and technological weight has only to a limited extent been matched by political influence, but history shows that an increase in economic power over time translates into increased political power. The current debt and financial crisis in the Western countries has probably sped up the current shift of power, and countries both to the east and to the south are becoming more prosperous and gradually more powerful. However, these new global power relations have so far not manifested themselves in the UN system. The traditional roles and groupings of the emerging powers have remained unchanged, and the polarisation between North and South remains the same.

Figure 1.4 Liberia.

Source Photo: UNICEF/Giacomo Pirozzi

UN activities are influenced by the balance of power between the member states at any given time. In cases where the Security Council cannot arrive at a decision, it is because the member states do not agree. The relevance and influence of an emerging power are decided by its approach to the UN as a whole and to its different institutions and views on important issues. If Norway is to maintain its influence and gain acceptance for its interests and priorities in the UN and its activities in the years ahead, the Government needs a sound understanding of the positions of the various actors and to be able to build alliances with different member states.

New and traditional major powers. In general, major powers take a more selective approach to multilateral institutions than smaller countries, which are more dependent on rule-based international cooperation. The question now arises whether the current emerging powers will follow the example of the older ones. The five permanent members of the Security Council (China, France, Russia, the US and the UK) still play a very significant role in the UN.

No other country has anything like the same possibility to influence the international agenda as the US. Under the Obama Administration, the US has had a stronger focus on the UN and has paid its arrears to the Organisation. The US and certain European countries have been part of the first group of major powers since the beginning, and have shown varying degrees of support for the UN system. They finance most of the regular UN budget and operational activities. The question now is whether the US and a Europe in financial crisis are still willing to take on the burden of global leadership they have borne since the end of the Second World War. So far no other country seems to be ready to play a leadership role.

China and Russia, as permanent members of the Security Council, also belong to the group of major powers, and have made use of the UN when they have considered it expedient. They have taken fewer initiatives, put fewer issues on the agenda, and in general defended the status quo. A number of emerging powers have expressed the wish that the UN and the international financial institutions should to a greater extent reflect the reality of a multipolar world. The UN is an important institution for balancing the interests of major powers. Negotiations in the UN are marked by both offensive and defensive interests and exercise of power. The Western countries have traditionally taken the offensive and been drivers of international cooperation by taking new initiatives and putting new issues on the agenda. Examples of defensive interests are curbing development in particular areas or preventing new issues from being raised. All the member states have offensive and defensive interests in relation to the UN. If all the major actors concentrate purely on their own interests, one of the consequences of the financial crisis could be a greater pulverisation of responsibility.

The emerging powers are not a uniform group, and have their own agendas on peace and security, trade, global governance, environment and development. The UN is generally regarded by these states as an important arena for addressing certain global challenges, primarily because of the principles of sovereign equality and non-intervention laid down in the UN Charter. Generally speaking, most of the emerging powers have a national focus and make use of the institutions where they consider it expedient. A number of the states in this group consider reform of the Security Council to be an overriding issue, and claim that it is necessary in order to maintain the legitimacy of the UN. However, these countries lack a common approach to the content of such reform. Although agreement on the content of reform is unlikely within the next few years, the countries are likely to keep up their demands for reform. They are also demanding more proportional representation in other forums, and in particular that their interests and issues are reflected on the agenda. If reforms are not undertaken, this could over the long term weaken the UN’s relevance for these countries and thereby its relevance as a global actor.

There are several possible scenarios for the time to come: 1) the emerging powers will make more use of the UN in areas where it suits their national interests, 2) they will give preference to minilateral forums and informal groups in order to gain more influence on international affairs, or 3) they will make more use of bilateral relations. The consequence of the last two scenarios will be to marginalise the UN.

Group dynamics and governance challenges. Negotiations in the UN usually take place between two blocs – North and South. The G77 and the Non-Aligned Movement include a varying number of the developing countries and China, depending on the issue in question. The North includes the Western countries, mainly represented by the EU and the US. At the same time certain countries, like Norway, Mexico, Switzerland and New Zealand, often have a more flexible approach and are able to help engineer compromises. Since the EU achieved a new status in the General Assembly after the adoption of the Treaty of Lisbon, it often speaks and negotiates as a single voice on behalf of its member states.

An undesirable consequence of the two-bloc system is that it is often the countries with the most uncompromising views that have the greatest influence. This tends to result in polarised positions, making negotiations difficult and sometimes halting them altogether, for example in discussions on funding.

Although most negotiations in the UN are conducted between blocs, the dynamics vary depending on the forum concerned. The general meetings of the specialised agencies, the boards of the UN development and humanitarian organisations, and other, more technical, groups are less prone to politics and polarisation.

1.1.4 Global governance, organisation and division of labour

New needs and the ineffectiveness (genuine or perceived) of existing UN organisations have led to strong growth in the number of actors in the international arena in the last few decades, mainly outside the formal organisations, to which all countries have access. A number of political processes and decisions are being shifted to new arenas and actors such as the G8 and the G20. Informal summit meetings are continually being held that compete for the attention, resources and implementation capacity of the different countries. UN member states are drawn towards other forums. And actors such as private funds and foundations are seeking to exert more influence in intergovernmental forums.

Informal groups and networks. When the G20 emerged as the main global actor in connection with the financial crisis, it was feared that it would intervene in areas that were part of the UN’s sphere of influence. This fear was founded on the fact that the G20 is a self-appointed organisation whose members represent 80 % of the global economy and also of the world’s population. Furthermore the UN has not in principle been given the mandate or the competence to play a strong role in the macroeconomic field. On the other hand, the Organisation is in fact playing a role in efforts to deal with crises in connection with the possibility of global recession, for example as a catalyst for new ideas in the economic field and as a watchdog for established rules and standards. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), for example, served as a catalyst for an inclusive green economy by its prompt action in setting agendas and making knowledge available. The debt and unemployment crisis that has so deeply affected parts of Europe and the US has forced the international community to think along new lines about employment and growth. The UN’s role, as represented by the specialised agencies ILO and UNIDO and through its relations with the multilateral financial institutions, has become more relevant owing to the fact that the crisis has a high place on the agenda and that the member states are developing new policies to address it.

Textbox 1.1 The International Labour Organization (ILO) and decent work

The ILO has developed a system of international labour standards which is maintained through the ILO conventions and backed up by a supervisory system to ensure their application at national level. The Government has given priority to decent work in foreign, development and trade policy. Promoting decent work includes combating child labour, forced labour and discrimination, and promoting freedom of association, gender equality and the right to collective bargaining. The fundamental principles and rights at work safeguard fundamental human rights and promote the sustainable development of society.

The Government’s decent work strategy was launched in 2008. It is based on the ILO decent work agenda, which has four strategic objectives: employment creation, rights at work, social protection and social dialogue. Norway is also a large contributor to development programmes promoting decent work at country level, in which ILO cooperates with the authorities and the social partners.

The G20 is to a growing extent seeking partnership with the UN in cases where the mandate and knowledge of the Organisation and its specialised agencies are relevant. The Secretary-General and various UN organisations are involved in G20 processes and are given tasks by the G20. As the world’s 24th largest economy, Norway is interested in influencing discussions and decisions in the G20, and we have put forward a proposal for joint Nordic representation. The Norwegian Foreign Minister participated in a meeting prior to the G20 meeting in Mexico. We will continue to seek contact and influence in the G20, and our goal is joint Nordic representation on a permanent basis.

Shifting power relations and new ambitions can lead to greater competition. The existence of a larger number of equal actors may make it more difficult to reach agreement. When emerging powers do not feel they have sufficient influence in the UN, they may seek other forums and form other groups, such as the BRICS1 countries, the IBSA2 Dialogue Forum and the BASIC3 cooperation. So far there are few indications of systematic coordination between different groupings within the UN, but the IBSA countries coordinated their positions during the period when they were all members of the Security Council. If these forms of cooperation are institutionalised and are preferred to existing UN institutions, they are likely to weaken the latter’s relevance. An example of this form of cooperation is the idea of the BRICS development bank.

Regionalisation. Chapter VIII of the UN Charter opens the possibility of regional cooperation arrangements within the UN. Regional actors are becoming stronger, and several have developed cooperation mechanisms, common approaches and standards on for example economic and environmental issues, use of resources, human rights and crisis management. Among the most important are the African Union, NATO, ECOWAS, the Arab League, ASEAN and the EU.

Regional and sub-regional solutions are often more effective than global solutions. For example, the UN cooperates with regional organisations on crisis management, and provides capacity-building expertise and technical advice to strengthen the regional organisations’ crisis management capability and ability to participate in peace operations. Regional organisations are often in a good position to assist in crisis management due to their presence, knowledge of the challenges, experience of how to reach solutions, and understanding of the intentions of neighbouring states. Regional actors often operate with a mandate from the Security Council and in line with the UN’s normative framework. There is a strong focus on this work in the UN system, and active efforts are being made to further strengthen the cooperation.

Norway considers it important to continue its efforts to ensure that the work of regional organisations is based on the international legal order and negotiated global standards and norms.

Non-state actors: philanthropic organisations, the private sector and civil society. The growing influence of non-state actors and markets is a factor for change that is affecting the UN. The Organisation is to an increasing extent participating in public–private cooperation with global foundations and the private sector. Civil society and NGOs also play important roles in setting agendas and as watchdogs and partners in implementation.

Private actors like global funds and large foundations such as the Gates Foundation are becoming increasingly important in the development field and provide substantial funding for development, some of which is channelled through UN agencies. The global funds were established to answer the need for more targeted action in strategic areas, and have produced good results. However, a challenge for the UN, as an intergovernmental organisation, is that actors that make major contributions are seeking to influence priorities and the use of funds, and are having a growing influence on political agendas. In order to continue to attract financing from these private actors, the UN will have to allow them a certain degree of influence. However, it is important that, while opening the possibility of new forms of cooperation, the Organisation should ensure that these are based on the UN normative framework. A frequent solution is to establish new initiatives or public–private partnerships outside established institutions, although lack of capacity to follow up initiatives is also a problem. Norway has played a leading role in several such initiatives and is making efforts to ensure that private actors can participate as far as possible in discussions in established forums.

Textbox 1.2 Cooperation with global funds in the health sector

The establishment of global schemes and funds was the result of the need to mobilise more resources and achieve results more rapidly and effectively by targeting specific areas. At the same time, it was made a condition that the efforts should be based on the UN’s normative mandate. The multilateral health organisations are therefore co-owners of the global funds on a par with donors from the private, public and voluntary sectors. The global funds have been criticised for fragmenting aid efforts and undermining the UN system by assuming tasks that should really be performed by the UN. On the other hand, the funds have provided substantial increases in resources and improved performance management.

The UN also serves as initiator and catalyst for contact between the private sector and developing countries interested in investment, although it has a smaller role in implementation and service delivery. The growing prominence of the private sector in the UN is making it necessary to discuss how to impose international obligations on non-state actors. This is being debated in several arenas, including the UN Guiding Principles on Human Rights and Business, and ILO, which has a tripartite structure consisting of government, employers and worker representatives. The interface between the UN system and the private sector also includes the UN Global Compact, which is open for participation by governments, companies, business associations, labour organisations and civil society. The Global Compact is founded on 10 universally accepted principles in the areas of human rights, labour, the environment and anti-corruption. Norway has played a leading role in the Global Compact and in the work on corporate social responsibility.

Figure 1.5 Round-table conference with Egyptian youth activists and Secretary-General Ban-Ki-moon. Cairo, Egypt, 2011.

Source Photo: UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe

Civil society plays many different roles in relation to the UN system: initiator, driving force and pressure group for the adoption of new norms and standards, watchdog to ensure that member states comply with their commitments, and implementation partner on the ground in development and humanitarian operations. Civil society’s engagement in the Human Rights Council has a role in holding states accountable, and reports from civil society have the status of formal documents in the Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Reviews. In addition, over 3 000 NGOs have consultative status in ECOSOC. In some cases NGOs also have access to other UN forums, for example in open debates in the Security Council and the Human Rights Council. Norwegian NGOs and academic institutions are actively involved in the UN system as participants in UN forums, partners in the field and contributors to reform through research and participation in various processes.

Textbox 1.3 The International Energy and Climate Initiative, Energy+, and Sustainable Energy for All (SE4All)

The Government’s Energy+ initiative was launched by Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon at a conference in Oslo in 2011 entitled Energy for All: Financing Access for the Poor. A total of 1.3 billion people lack access to modern forms of energy, but at the same time it is crucial to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions. Energy+ aims to address this challenge by using development aid to reward developing countries whose efforts to provide universal access to sustainable energy and reduce greenhouse gas emissions have shown results. Development aid will also be used to promote far greater private investment in the energy sector. Energy+ is a two-year pilot project, and the Government will decide whether to continue it at the end of the trial period.

A number of countries, international financial institutions, commercial companies, UNDP, UNEP, the World Bank and NGOs, including NORFUND and McKinsey Norge, are partners in Energy+. The project is also a tool for implementing the Secretary-General’s initiative Sustainable Energy for All (SE4All), which has three ambitious objectives that are to be fulfilled by 2030: universal access to modern energy services, doubling the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency and doubling the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix.

Civil society organisations are important agents of change for promoting human rights on behalf of the population as a whole and of vulnerable groups such as people with disabilities, people living with HIV, and girls and women who have undergone female genital mutilation. Globalisation and modern technology have given civil society a much stronger voice, which means that UN member states are forced to take civil society actors into account to a much greater degree than before. Not all member states wish to hear a strong voice from these actors at UN meetings, and attempts are continually being made to restrict their access, most recently during the negotiations on the Arms Trade Treaty in summer 2012. Norway considers that civil society, including NGOs, has an especially important role in contributing country-level views and experience to global discussions, and will continue to advocate that these actors have general access to UN meetings. In cases where access is restricted, Norway will seek to have representatives of civil society included in national delegations. We should also work for an agenda where the UN in the field promotes the establishment of arenas for civil society and mechanisms for enabling these actors to influence national policies.

The UN system. The international financial institutions, the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the International Atomic Energy Agency and a number of other organisations that were established through negotiations under UN auspices are related to the UN. They are autonomous bodies but have special agreements with the UN and are part of ECOSOC. They also participate in the UN Chief Executives Board, an advisory body for the Secretary-General that promotes coherence and cooperation within the UN system.

Enhanced cooperation and contact is needed between the UN on the one hand and the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on the other. At the intergovernmental level, a closer dialogue is needed between the UN General Assembly and the boards of the World Bank and the IMF. A high-level conference hosted by Prime Minister Stoltenberg was held in Oslo in autumn 2010 on the challenges to the international labour market posed by the financial crisis, which left millions of people out of work. The conference was arranged in cooperation with ILO and the IMF.

The World Bank should also cooperate more closely with the UN at country level. The two organisations still have overlapping mandates and compete in many areas instead of agreeing on a division of labour and cooperating on common goals. There is a growing tendency for the World Bank to work in areas that have traditionally been regarded as being the sphere of the UN, for example health and education, and in fragile states. Furthermore, many member states pursue contradictory policies in the UN and the World Bank. The Government believes that the World Bank and the UN have different strengths and should play complementary roles, and closer cooperation should therefore be sought in contexts where they both participate. We have put pressure on the organisations to cooperate more closely, and have noted good results in several areas.

1.2 Norway’s influence and room for manoeuvre

In a constantly changing landscape, cooperation must be sought on a case-by-case basis, and Norway must seek opportunities to build strong alliances on issues that are in our national interests or of international interest. The Government gives priority to forming new alliances to promote our foreign policy goals.

The US, the Nordic countries and other Western countries in the EU have always been among Norway’s closest partners in the UN. Many of our interests and priorities are also shared by Canada, Switzerland, Australia and New Zealand. All these countries will continue to be important partners for Norway.

The most permanent of our alliances has always been our cooperation with the other Nordic countries. However, the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy, which is also being pursued in an increasing number of cases in the UN, is affecting Nordic cooperation. Although Nordic collaboration continues to be close on an informal case-by-case basis, it is naturally influenced by the fact that three of the Nordic countries have to take EU positions into account and are part of EU negotiation dynamics. The exception is participation in the Security Council and the governing boards of UN organisations, where the EU does not speak with one voice and Nordic cooperation is close. Nordic cooperation in UN elections is based on Nordic agreements on rotation arrangements and mutual support in many key UN entities such as the Security Council, the Human Rights Council and ECOSOC. This is of great benefit to Norway, since it means that we are represented more frequently than we would otherwise be. The Nordic countries also discuss joint military contributions to UN peace operations, and cooperate closely in the governing boards of UN funds and programmes, for example on assessing the organisations. The Government will continue to further develop Nordic cooperation.

Geopolitical changes are making it more important than ever for Norway to cooperate more closely with other countries as well as those mentioned above, including emerging powers. We need to identify areas where we have common interests with emerging powers and strengthen our cooperation with these countries through strategic alliances on a case-by-case basis or through more extensive partnerships, such as Norway’s climate and forest cooperation with Brazil and Indonesia. These countries are also part of the seven-country cooperation on Global Health and Foreign Policy. UN peacekeeping operations, women, peace and security, conflict resolution, and peace and reconciliation are other important areas for cooperation with emerging powers.

At the same time Norway intends to actively support the least developed countries on a number of issues where our interests coincide, including the environment and climate change, poverty reduction, development and post-conflict reconstruction.

Textbox 1.4 The Millennium Development Goals – examples of Norwegian priority areas

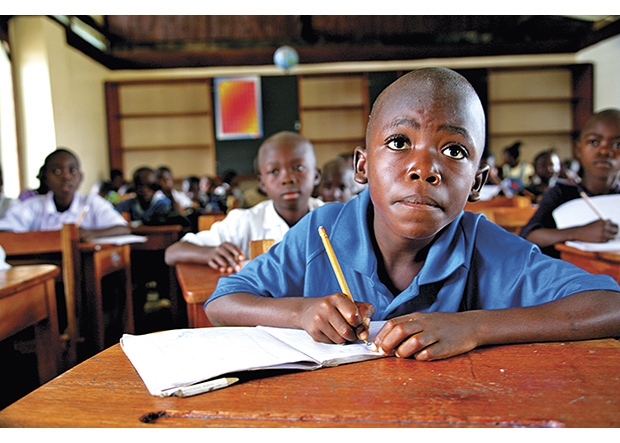

MDGs 2 and 3: Education, with a focus on girls’ education

Norway has maintained a focus on girls’ education for many years. The target of MDG 2 is to ensure that all children are able to complete primary schooling. Currently nine out of ten children enrol in primary school and 90 % of them complete it. Great progress has been made in sub-Saharan Africa, where school enrolment increased from 58 % to 76 % from 1999 to 2010. The target for MDG 3, eliminating gender disparity in primary and secondary education, has been reached. Today as many girls as boys enrol in primary school at the global level, although there are still disparities in many individual countries.

Norway was the main contributor to the African Girls’ Education Initiative (AGEI). This formed the foundation for UNGEI (UN Girls Education Initiative) and has played a key role in UNICEF’s efforts to promote girls’ education. In 2012 Norway contributed NOK 550 million to UNICEF’s Girls Education Thematic Fund, making us the main contributor to UNGEI. An evaluation of UNGEI showed that the initiative has raised awareness at global, regional and country level of the importance of focusing on gender equality in efforts to promote education.

MDGs 4, 5 and 6: Reducing child mortality, improving maternal health and combating communicable diseases (HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis)

The UN is an important forum and the UN organisations are important partners for Norway in promoting our priorities for the health-related MDGs. Our efforts are particularly directed towards child and maternal health, and prevention and treatment of communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. We also give priority to strengthening health systems, management of pandemics, addressing the global health workforce crisis, protection and promotion of sexual and reproductive health and rights, support for global health-related research and knowledge development, combating female genital mutilation, and, to an increasing extent, combating non-communicable diseases. MDG 5, improving maternal health, is the goal that is furthest from being achieved by 2015, but the 2010 figures show substantial progress, from over half a million deaths a year in 1990 to less than 300 000 in 2010. MDG 4, reducing child mortality, has also shown considerable progress since 1990. Mortality for children under five was reduced by 35 % from 1990 to 2010.

Preventive measures against malaria and better access to vaccination and HIV medicines have contributed substantially to these improvements.

The Global Campaign for the Health Millennium Development Goals was launched in 2007 by Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg. The purpose was to mobilise political support for the health-related MDGs, attract more funding for health care in poor countries and ensure that the money is well spent. In the same year he established a network of 11 heads of state and government to work for these objectives. Cooperation with the UN has played a central role in the Government’s efforts to promote these MDGs. In 2010 Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon launched the campaign “Every Woman, Every Child”, which brings together states, UN organisations, civil society, professional organisations, research and higher education institutions, and the private sector in a joint effort to implement the Global Strategy for Women’s Health. The strategy aims to enhance financing, strengthen policy and improve service on the ground for the most vulnerable women and children. Norway was involved in developing the strategy, and the Government is giving priority to following it up. Vaccination programmes are an important tool in the efforts to achieve the health-related MDGs. In this field the UN organisations, especially WHO and UNICEF, cooperate closely with the GAVI Alliance, to which Norway is a major contributor.

In March 2012 the new UN Commission on Life-Saving Commodities was established (in connection with Global Strategy for Women’s Health). The commission works to improve access to life-saving medicines and other health supplies, including contraception, to reduce child and maternal mortality. The commission is co-chaired by Prime Minister Stoltenberg and Nigeria’s President Goodluck Jonathan. The commission submitted its final report and recommendations at the UN General Assembly in September 2012.

Since spring 2012 Norway has also been a partner in the cooperation Saving Mothers, Giving Life together with the US and others. The first two pilot countries are Zambia and Uganda.

When forming alliances with emerging powers and others, Norway needs to project a clearly defined image at the UN, together with explicit priorities and positions. These should be based on:

a predictable and recognisable policy in areas where Norway has credibility and experience from which others can benefit,

a clear, consistent voice across all forums,

financial and human resources for lifting our priorities higher up the agenda,

alliances across regional borders, with new actors and with civil society, both from case to case and in the form of long-term strategic alliances and partnerships,

a willingness to promote new ideas.

A sound analysis of national positions in different thematic areas will be crucial for forming the alliances we need in order to exert influence in the UN of the future. Our foreign service missions will have an important role in linking the dialogue at UN headquarters with capitals. Building alliances in the UN is to an increasing extent taking place outside UN forums, with important partners at the capital level. An example of targeted efforts by Norway was the initiative for a new global agreement between port states to combat illegal fishing. Within three years of the decision in the General Assembly, a binding agreement between the parties was reached under the auspices of FAO. The work was financed by Norway, and the Port State Measures Agreement establishes international minimum port states measures based on the Norwegian system.

Norway will continue its policy of seeking close contact with institutions and civil society, and will serve as a door opener for civil society in UN meetings and processes. Access to these is under pressure from countries that wish to avoid critical voices by closing UN meetings and processes on the grounds of the principle of sovereignty. The rules of procedure do not allow NGOs to become members of boards or participate in decision-making processes at the intergovernmental level. We will work to prevent attempts to close debates and processes, and defend the adoption of an open approach to access by civil society.

Textbox 1.5 Norway as an advocate of UN reform

Norway has played a leading role in the efforts to integrate UN peacemaking activities with other parts of the UN system. These efforts have resulted in substantial changes both at headquarters and in the field, in the form of a common framework for identifying the needs to be taken into account when planning peace operations. As a result UN peacekeeping efforts are better coordinated with humanitarian operations. Planning and coordination focus on short- and long-term humanitarian needs and on the more long-term development agenda in fragile states in or emerging from conflict. The establishment of the Mediation Support Unit, and the Standby Team of Mediation Experts initiated and supported by Norway, has strengthened the capacity for conflict prevention of the Secretary-General and the Secretariat. A new model has been set up for coordinating and financing humanitarian assistance.

Norway has made a substantial contribution to reform of the UN development system. As early as 1996 the Nordic project for UN reform contained a proposal that the UN should integrate its development efforts at country level. Ten years later Prime Minister Stoltenberg was co-chair of the High-Level Panel on System-Wide Coherence to strengthen UN development efforts. The Panel’s report, Delivering as One, has resulted in extensive changes in the way UN organisations work at country level, and strengthened host countries’ sense of ownership. The Panel also proposed the establishment of a new entity to coordinate and administer the UN’s work on women’s rights and gender equality. UN Women, which was established in 2010, was a merger of four previously separate parts of the UN system. The new entity was a considerable step forward in the reform process and a victory for the efforts to promote women's rights and gender equality.

1.3 Strengthening the UN and making it more effective

The UN of today is quite different from what it was at the end of the Cold War. Former Secretary-General Kofi Annan stated that reform is a process, not an event. In order to address the new challenges and framework conditions, all UN organisations must continually adapt and change. Reform needs to be part of the organisation’s day-to-day activities. Sometimes the need arises for a major reorganisation, usually in the wake of major upheavals or crises. Today the UN faces a twofold challenge: internal power relations need to reflect current realities more closely, and the international community’s ability to control and regulate more complex global problems needs to be improved. It is in the interests of Norway and like-minded countries to follow both tracks.

Norway’s interest in well-functioning multilateral institutions and as a major contributor to the UN has made it an advocate of reform from the start.

Demands for UN reform have been put forward ever since the Organisation was founded. One of the most widespread criticisms is that the UN system is inefficient and bureaucratic. There can be no doubt that the way the UN is managed should be improved. The Secretariat and the various funds, programmes and specialised agencies have problems due to inefficiency, lack of proper documentation of results, and bureaucratic (sometimes antiquated) administrative systems and procedures. Areas such as human resources management, recruitment, internal control and transparency need to be considerably improved. Simplification and harmonisation of administration across the UN system are essential, since the various organisations have different administrative systems and procedures. Norway is working for reform in these areas.

At the ideological level, conservative voices have alleged that the UN restricts states’ freedom of action. Critics at both ends of the North–South spectrum fear the development of supranational governance on the one hand and rejection of attempts to regulate what are perceived as internal affairs on the other. The conservative right in the US has accused the UN of aiming at world governance, while critics in the South accuse the Organisation of serving the interests of the Western countries and practising neocolonialism and imperialism. The latter seek to maintain control through overregulation, especially through the UN Budget Committee (the Fifth Committee), while the former deny that the UN has any relevance and argue in favour of going it alone.

Textbox 1.6 Financing the UN

The UN regular budget: USD 5.15 billion with a two-year budget cycle (NOK 15.7 billion a year)

The UN peacekeeping budget: USD 7. 6 billion (NOK 44 billion) in 2012

UN operational activities (development, humanitarian assistance): USD 22 billion (NOK 134 billion) in 2010

Norway’s contribution in 2012 is 0.871 % of the total budget, and consists of NOK 121.3 million to the regular budget and NOK 380 million to the peacekeeping budget. Norway’s total contribution to UN development and humanitarian activities was NOK 7 billion in 2011. We are one of the three largest donors to UNDP, UNICEF and UNFPA, but our contributions do not amount to more than 5 % of the organisations’ total income.

Mandatory contributions and assessment scale: The regular and peacekeeping budgets of the UN are covered by the member states’ mandatory contributions. These are assessed according to each state’s ability to pay, and the minimum assessment rate is 0.001 %, with a maximum assessment rate of 22 %, of the regular budget (or 25 % of the peacekeeping budget). The assessment rates are based mainly on GNI, but exceptions are made, for example for countries with a high debt level or in the event of longer-term economic changes (based on average statistical base periods of three and six years). Because of the exceptions, the world’s second largest economy, China, is assessed at 3.189 % of the regular budget, while the assessment rates for the US, which is the world’s largest economy, are 22 % of the regular budget and 25 % of the peacekeeping budget. The assessed contributions from the permanent members of the Security Council account for a larger share of the peacekeeping budget than of the regular budget, and those from the least developed countries a smaller share. For the other member states the assessment rates are the same. The EU countries pay a total of around 40 % of the regular budget (their share of the world economy is 30 %), Japan pays 12.53 % and India pays 0.534 %. The assessment rates are reviewed every third year.

The member states have the overall responsibility for management of the UN. Only they can decide that a particular task should be given less priority. Reviewing and removing some of the thousands of tasks the member states have imposed on the UN would make the Organisation more efficient, but the member states lack the political will to take control and to act consistently across the different forums. The freedom of action and ability of the Secretary-General and other UN leaders to make changes in the organisation are hampered by the detailed rules imposed by member states.

Reform fatigue in the UN and a widespread scepticism about comprehensive reform mean that changes will continue to be introduced in small steps. The Secretary-General is in the process of making administrative changes. Better recruitment procedures that ensure that the right person is in the right place at the right time, greater transparency, result-oriented budgets and simpler administrative systems and procedures at headquarters level are being introduced. The Secretary-General has Norway’s full support in these efforts.

There are three areas in particular where UN organisations need to be strengthened: financing, leadership and partnership. How can we ensure that the resources match the mandate and that UN activities are financed in a way that promotes effectiveness? How can we ensure on the one hand that the member states assume clear ownership and management, and on the other that the central- and country-level heads of UN organisations are made responsible for achieving results? How can we make the UN more attractive as a partner and ensure that it has the flexibility necessary to form the most beneficial partnerships? The Government intends to strengthen the UN in all three areas, and these questions will be discussed extensively in the thematic chapters below.

If the UN is to play a key role in the years ahead, this will require not only a willingness to act on the part of UN leaders but also political will and financial support on the part of the member states.