2 Peace and security

Peace and security are at the core of the UN’s activities. However, today’s security challenges are far more complex than those existing at the time the UN Charter was signed. They include internal armed conflicts, gross violations of international humanitarian law (including genocide) and human rights, poverty, communicable diseases, climate change and environmental damage, weapons of mass destruction, terrorism and organised crime. Multilateral efforts to promote disarmament and non-proliferation are under serious pressure, and could develop into a new nuclear arms race. The situation is intensified by the growing importance of non-state actors.

The complexity of the threats makes it necessary to examine the UN’s traditional approach with fresh eyes, and consider equipping the Organisation with a broader set of instruments. For example, the UN’s work for economic and social development, and its efforts to promote international humanitarian law and human rights, could be used to address many of the current threats. As in other areas, the success of UN efforts will depend on close cooperation between the UN and other actors, and on involving regional organisations, individual countries and NGOs.

2.1 New threats and patterns of conflict

The statistics for existing conflicts show that conflict resolution and peacebuilding get results. In spite of a slight increase in 2011, the total number of armed conflicts has declined considerably since the UN was founded, and especially since the end of the Cold War. Armed conflict between states has become a rare occurrence. Much of the credit for this state of affairs can be attributed to the fact that the UN has been largely successful in its primary task. The number of armed conflicts within states has declined significantly as well, although the number is still considerable. Internal conflicts tend to spill over national borders and affect neighbouring countries. Conflict-affected countries, many of them situated in Africa, are often poor and the repercussions of a conflict are extensive. There are usually underlying political and economic problems, and in many cases the picture is complicated by organised crime, plundering, and illegal economic activities. Organised crime weakens institutions and makes states vulnerable, a situation that often affects neighbouring countries and other parts of the world. Since most of the victims of existing conflicts are civilians, the result is widespread suffering and hardship, with destroyed livelihoods, displacement, threats and violence, undernourishment, epidemics and other health risks, and a lack of educational services.

Changes in the security picture still pose a major challenge for the UN. Powerful states that choose to exercise their sovereignty are often reluctant to allow the UN to play a role in their internal conflicts. In addition it has been and still is difficult for the UN to assume a clear political role in some of the most prolonged conflicts, like that in the Middle East. Although the issue of the Palestinian Territory is one of the items that most often appears on the UN agenda, the Organisation is not in the best position to lead the political efforts to resolve this conflict. On the other hand, the UN plays an invaluable role in many of the operational activities on the ground.

In spite of these factors, the new conflict patterns also strengthen the UN’s relevance, since the Organisation has a greater breadth of tools at its disposal than any other actor. The toolbox for preventing and managing conflicts and supporting fragile states is becoming increasingly well equipped. Norway has played a leading role in this process and will continue to give it priority. We consider it important that the UN develops appropriate norms, strategies and forms of cooperation for addressing new threats.

2.2 The UN Security Council: legitimacy and effectiveness

The Security Council is the most powerful UN institution, and when a serious crisis occurs, this is the body to which the world turns. The Council’s main task is to maintain international peace and security. It has a broad set of conflict management tools at its disposal, ranging from diplomacy to the offensive use of force, and including mediation, political operations, peacekeeping operations, sanctions and military intervention.

The Security Council consists of five permanent members – the US, Russia, China, the UK and France – which have the power of veto, and 10 non-permanent members elected for two years at a time. However, the Council is only as effective as its 15 members allow it to be. The permanent members have a special responsibility by virtue of their veto power. Norway’s most recent term on the Security Council was in 2001–02, and we will again be a candidate for a non-permanent place for the period 2021–22. We intend to work hard to achieve this, and if we are elected we will put a great deal of time and effort into making a success of our time on the Council.

Figure 2.1 The UN Security Council.

Source Photo: UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe

The new conflict patterns have challenged traditional thinking about security, and new items are being put on the Security Council agenda. The close links between security and development have been recognised, and the Council now discusses questions such as the protection of children in armed conflicts and women’s role in conflicts (see Box 2.1). The Council is an influential norm-setter in these areas. Other items on the Council’s agenda are climate change, health, and transnational organised crime such as smuggling, human trafficking and piracy.

Textbox 2.1 UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) on Women, Peace and Security

Since 2000, the Security Council has unanimously adopted five resolutions on women, peace and security (nos 1325, 1820, 1888, 1889 and1960), all of which acknowledge the importance of women’s participation in peace operations, peace processes and post-conflict reconstruction. The resolutions require that girls and women are protected against abuse, and state that sexualised violence can constitute a war crime and a crime against humanity.

Norway has been actively involved in strengthening the implementation of these resolutions. The UN bodies that are intended to ensure international peace and security are obliged to mainstream a gender perspective and put women’s rights on the agenda in conflict situations. Peacekeeping and peacebuilding efforts have to address women’s needs and draw on women’s experience. This applies not only within the UN but also to other organisations tasked with peace operations, such as NATO and the African Union. In 2006 Norway launched an action plan for implementing resolution 1325, and in 2011 more targeted measures were included and a strategic framework was drawn up for its implementation.

2.2.1 The Responsibility to Protect – state sovereignty versus the international community’s responsibility

A cornerstone of the United Nations Charter is the principle of the sovereign equality of all its member states and the corresponding principle of non-intervention. However, the prohibition on intervening in the internal affairs of another state is qualified by the provisions of Chapter VII. Article 39 states that: “The Security Council shall determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression.” In such cases the Security Council has the authority to use force. However, in cases of lack of agreement in the Security Council on this issue, the international community has time after time stood helplessly by while genocide, ethnic cleansing and other gross abuses of civilians were being practised inside national borders. At the same time the idea of the fundamental human rights – inviolable and universal – is deeply rooted in the preamble of the UN Charter. As a consequence of the wars in the Balkans and the genocide in Rwanda, it was agreed at the High-Level Plenary Meeting of the General Assembly in 2005 that the two principles were not necessarily in conflict if the concept of sovereignty was interpreted as “sovereignty as responsibility”. In the Outcome Document the participants committed themselves to the principle of the Responsibility to Protect, which was later reaffirmed by the Security Council.

Figure 2.2 Zawiya, Libya. The one-year anniversary of the start of the anti-Gaddafi uprising.

Source Photo: UN Photo/Iason Foounten

Textbox 2.2 The Responsibility to Protect

The principle of the responsibility to protect has a firm basis in international law. Norway supports the broad set of tools required to enforce the principle, especially preventive measures and the use of peaceful means. We advocate the view that the legitimate exercise of power depends on the safeguarding of citizens’ fundamental rights, and that preventive international intervention may be justified in the case of states that fail to safeguard these rights. However, Norway also believes that the use of armed force requires a mandate from the UN Security Council.

2.2.2 Reform of the Security Council: legitimacy versus effectiveness?

Reform of the Security Council is the single topic that more than any other influences the relations between the member states. The countries of the South are demanding that the membership of the Council should reflect more closely today’s geopolitical reality and not the world as it was in 1945. They feel that the existing composition of the Council weakens the Organisation’s legitimacy.

The issue is an underlying theme in much of the UN’s work, and in many cases creates a difficult negotiation climate in which the lack of Security Council reform is used as an argument to reject reform in other areas. India raised the issue as early as 1980, and most of the member states now agree that reform of the Security Council is necessary. However, intergovernmental negotiations are being blocked by strong disagreement on the composition of the new Security Council, and there is little sign of a breakthrough. The greatest difference is between the views of the G4 countries (India, Brazil, Japan and Germany), which are demanding a permanent place on the Council, and those of the United for Consensus Group (among which are Canada, Italy, Spain, Mexico, Argentina and Pakistan), which will only support an expansion consisting of non-permanent or semi-permanent members. The African countries are demanding both that Africa is given two permanent places and that the number of non-permanent places is increased.

Another central issue in the negotiations is the power of veto – whether the existing permanent members should renounce their veto power and/or whether new permanent members should be given such power. The existing five permanent members do not wish to renounce their veto and have made it clear that they do not consider that new permanent members should be granted veto power. The G4, especially India, is demanding a permanent place with veto power. The African countries consider that if the five permanent members retain their veto the new permanent members should also be given a veto.

Competition for the non-permanent places has always been stiff, and is becoming even stiffer. This applies particularly to the Western and Other States Group (WEOG), to which Norway belongs, and the Group of Eastern European States. The margins are often very narrow, and states have to submit their candidacy many years in advance.

Norway considers that the Security Council needs a fundamental reform. The main goal must be to ensure that it has the necessary effectiveness and legitimacy to address the threats to international peace and security, while at the same time reflecting the current division of power and having a more representative membership. Permanent regional representation is one possibility. As long as such fundamental reforms are not supported by the member states and the permanent members of the Security Council, Norway will continue to back the candidacy of individual states to semi-permanent or new permanent places without a veto. Norway considers it important that the model that is finally chosen does not compromise the Council’s ability and willingness to act when action is called for. We will promote discussion of the different reform models and will maintain close contact with influential countries.

Another central topic in the debate on reform is the need to ensure greater transparency in the work of the Security Council. Norway has played an active role in these discussions. We support measures to increase transparency and involvement of non-members in the Council’s work, for example by strengthening the dialogue with the General Assembly, open monthly briefings by the Presidency, more information to non-members on peacekeeping operations, and closer dialogue with countries deploying police and military personnel in operations. We support the proposal that the five permanent members should explain their reasons for exercising their veto, and that they refrain from exercising it if this would block decisions to prevent or halt genocide, war crimes or crimes against humanity.

Since 2005, Norway has supported the not-for-profit organisation Security Council Report, which makes information on the Council’s work available to member states. The organisation publishes reports that reach a broad public and makes a valuable contribution to transparency and debate on the Council’s activities.

Textbox 2.3 Sanctions as a tool

Many member states are sceptical about the use of sanctions. It is claimed that they affect innocent third parties and constitute intervention in internal matters. However, a distinction must be made between the actual effects of implementing sanctions and whether imposing sanctions will achieve the political goal in question. There is a need for better understanding of how the different mechanisms can be used to achieve the different goals and for a global dialogue on the subject, for example on how the economic repercussions of sanctions should be dealt with, especially when energy issues are involved.

The Government will

work for reform of the Security Council to make it more legitimate and effective,

support efforts to improve the Council’s working methods and make them more efficient,

seek to enhance cooperation between the Security Council and other parts of the UN system.

2.3 The UN’s peacebuilding toolbox

The UN’s peacebuilding toolbox comprises prevention, mediation, political operations, sanctions, peace operations and peacebuilding.

Today, peace operations are not only intended to promote security, they are also expected to facilitate humanitarian assistance and promote peacebuilding and long-term development. Norway therefore considers it important to strengthen the UN’s capacity to fulfil the comprehensive mandates adopted by the Security Council, including the ability to maintain a focus on women and to take general human rights considerations into account. Much remains to be done before UN peacekeeping operations effectively fulfil and are in practice integrated with all the terms of their mandates. This will involve addressing the political and operational challenges discussed below. Norway will continue to actively support this process, in particular by emphasising women’s role in peace operations and peacebuilding, protection of civilians, and the need to safeguard humanitarian principles and the independence and freedom of action of humanitarian actors.

2.3.1 Political operations: prevention and mediation

The UN is in a particularly good position to act as mediator because it is perceived as impartial, without special interests that would be affected by the outcome of the process. The UN’s capacity has been considerably strengthened by the establishment of the Mediation Support Unit (MSU) under the Department of Political Affairs, and the UN Standby Team of Mediation Experts, established with support from Norway (see Box 2.5). The UN is also in a good position to play a coordinating role in conflicts where many different actors are involved in providing assistance.

Textbox 2.4 Reform processes and Norwegian support

The UN's peacekeeping capacity has been considerably strengthened in the last 10 years. The Organisation as a whole has addressed the challenges that arose in the wake of the crises in Somalia, Rwanda and the Balkans during the 1990s.

Norway has played an active role in the reforms that were and still are being implemented on the basis of the Brahimi Report of 2000, and has helped to develop the multidimensional, integrated approach that characterises peace operations today. Under this approach, all UN organisations engaged in peacekeeping on the ground cooperate with one another under the leadership of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General. The Special Representative has two deputy special representatives, who are responsible for development and humanitarian organisations, and for the political functions related to the operation, respectively. They draw up joint plans and are responsible for implementing the UN mandate on the ground.

Norway is a supporter and driving force in the development of guidelines for security sector reform and police work in peace operations. We also support the development of peacekeeping standards that define the results that can be expected from the various groups of personnel in the field. The aim is to make peacekeeping efforts more effective.

Mediation and conflict prevention are central elements of Norwegian foreign policy, and our experience of mediation and facilitation in conflict areas such as Nepal, Sudan, the Middle East and Sri Lanka makes us an interesting partner for the UN. We work closely with the Organisation on prevention and diplomacy in a number of countries, and will give this work high priority in the time to come.

For several years Norway has been putting pressure on the Department of Political Affairs to place more emphasis on women’s role in conflict prevention and resolution. We have financially supported the UN’s strategy for strengthening the role of women in peace negotiations and increasing the number of women peace mediators, and have funded the inclusion of an expert on gender equality in the Standby Team of Mediation Experts. We are promoting the efforts to protect women during and after armed conflicts, including the development of guidelines for including the issue of sexualised violence in ceasefire and peace agreements. The guidelines are intended to reduce the widespread use of impunity for this type of crime during and after conflicts. These efforts have resulted in a far greater focus on this issue, and we will maintain our engagement.

Norway has also worked for many years on strengthening the UN’s early warning mechanisms as a conflict prevention measure. The issue is a sensitive one, since many countries are suspicious of arrangements that could come into conflict with the principle of sovereignty. One of our main priorities in the time ahead will be to boost the UN’s capacity not only for early warning but also for early action.

The fact that UN political operations are financed over the regular budget, while many of the activities have to be financed by voluntary contributions, is a serious problem that results in lack of predictability. Norway will therefore actively promote the adoption of funding mechanisms for adequate and predictable financing of political activities, primarily by seeking to ensure that a larger share of political operations is financed over the regular budget.

2.3.2 Peacekeeping operations

Peacekeeping operations are the most central tool used by the UN to promote international peace and security, and it is in Norway’s interest that the Organisation continues to conduct such operations.

Textbox 2.5 The UN Standby Team of Mediation Experts

With funding from Norway and practical support from the Norwegian Refugee Council, the UN has established a multinational team of experts that can be deployed within 72 hours. The number has now been expanded thanks to EU support. The Norwegian Refugee Council and the UN Department of Political Affairs cooperate closely on management of the team. The Standby Team has been involved in more than 50 processes in every part of the world, for example in Yemen and Syria. UN special envoys, political and peacekeeping operations, UN resident representatives and regional organisations have all made use of its services. In summer 2010, the Refugee Council commissioned an external evaluation of the Standby Team, which concluded that it is a valuable resource, and emphasised the importance of using professionals who possess the necessary expertise.

Figure 2.3 Norwegian military observer Frode Staurset in Abyei, 2011.

Source Photo: private

Around 116 000 personnel are currently serving in 15 UN-led peacekeeping operations, most of them in Africa. The peacekeeping budget for the period 2012–13 is about NOK 44 billion, to which Norway contributes 0.871 %, or about NOK 382 million. The growth in peacekeeping operations has resulted in serious political and operational challenges, which must be solved if the UN is to continue to be relevant and effective at country level.

The political challenges of peacekeeping operations are linked to the question of which tasks the operations are mandated to perform, how much force is to be used, especially for protection of civilians, and what financial resources should be made available for the operations.

Since the mid-1990s, countries in the South have been largely responsible for supplying the uniformed personnel in UN peace operations, while countries in the North have been by far the largest donors of financial resources. Since over 90 % of the military and police forces come from countries in the South, these countries consider that they should have a greater influence on the content of the mandates in the Security Council. They also consider that the reimbursement rates for the expenses of participating in such operations should be raised. A number of key countries in the North are unwilling to support these demands since many of them are implementing austerity measures at home and since they consider that some emerging powers in the South should take on a greater share of the cost by increasing their financial contributions to UN peace operations.

Norway is seeking to improve the climate of cooperation between North and South, and to promote agreement on the form and content of operations and ensure that they have the necessary resources to accomplish the tasks mandated imposed by the Security Council. We will therefore continue to discuss the political and operational challenges with key countries in the North and South. In this process it will be important to motivate countries in the North to increase their contribution of uniformed personnel, since broad participation will strengthen the legitimacy of such operations.

The operational challenges of peacekeeping operations are caused by a lack of correspondence between the tasks the peace mission is expected to perform and the resources made available to it. It has proved extremely difficult to obtain the necessary personnel and equipment.

One of the conditions for success in this area is that the host country is willing to cooperate. Delays in issuing visas, refusal to admit personnel from certain countries and limitations on movements make cooperation difficult.

Today’s conflicts are often marked by an extremely difficult security situation, weak state structures, the involvement of many different actors and, not least, gross human rights violations. Norway supports the strong emphasis in UN peace operations on protecting civilians. This includes protection against conflict-related sexualised violence and measures for security sector reform in the host country. The latter is crucial if the host country is to be able to protect its civilian population. Norway therefore considers it important that in addition to robust military forces, operations should include police personnel and civilian experts, early warning systems and consultations with the local community. It is also important that they contribute to a well-managed political peace process.

Norway will play a proactive role in recruiting women to peace operations. About 30 % of the police and justice sector personnel in our standby rosters are women, and our goal is to increase this percentage. We are also seeking to ensure that both military and police personnel receive training that emphasises the importance of a gender perspective in the planning and implementation of all operations.

Today there is an increasing tendency for the UN to mandate regional organisations to conduct peace operations, in line with Chapter VIII of the UN Charter on cooperation with regional organisations. Not all regional organisations have the same operational capacity as the UN, and some have received UN support for capacity-building and logistics in the field. For example, the Organisation has provided both financial and material support for the African Union’s operation in Somalia, and is building capacity and providing technical advice on the development of the Union’s approach to security sector reform. It is in Norway’s interest that the UN continues to develop its cooperation with the regional organisations. The key issue is that the Organisation should retain its overriding role as a body for legitimising the use of force and implementing peace operations, whether the goal is peacekeeping or peace enforcement.

Textbox 2.6 Norwegian contributions to UN peace operations

Military contributions: since 2005 Norway has contributed to a number of UN-led operations. We supplied four motor torpedo boats for the operation in Lebanon in 2006/07, and together with Sweden we made available an engineer unit for the UN operation in Darfur in 2008, although this was rejected by the Sudanese Government. In 2009/10 we provided a well-drilling team and a field hospital in Chad. At the same time we increased our police participation in UN operations in Africa.

Our current military contributions are limited to around 30 staff officers and military observers in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kosovo, the Middle East and South Sudan. As our military participation in Afghanistan is being phased out, we will be able to provide greater military contributions to UN-led operations in a longer-term perspective. We are in the process of considering what kind of capacity we can make available. The contributions are most likely to comprise health personnel and engineers, both of whom will probably continue to be attractive since they are essential to the functioning of any operation. In spring 2012 Norway took the initiative to fulfil a long-held Nordic ambition to provide a joint military contribution to a UN-led operation. Cooperation with other countries is also a possibility, and our experience of cooperation with Serbia in Chad was positive.

Police contributions: Norway has relatively large contingents of police personnel in Haiti, Liberia and South Sudan. In Haiti we have provided a team of specialists to investigate sexual abuse. In Liberia we have financed the building of centres for women and child victims of abuse at a number of police stations, and Norwegian police have advised on measures to combat sexualised violence. Through the cooperation programme Training for Peace, Norwegian police personnel are also building capacity among African police to equip them for peace operations. Norwegian police personnel have long experience as instructors and leaders, qualities that are becoming increasingly necessary for UN-led operations.

The Government will

seek to strengthen UN conflict prevention efforts,

strengthen the bilateral dialogue with the UN on mediation and facilitation of peace and reconciliation,

provide political and financial support for envoys and mediators in conflict areas,

work to improve cooperation between the UN and other key actors involved in prevention and mediation in conflict areas,

take joint responsibility for international operations under the UN, NATO and the EU. Norwegian participation will be based on the UN Charter and have a clear UN mandate.

seek to strengthen UN peace operations,

give priority to participation in UN peacekeeping operations,

make it a goal to increase our contribution to UN-led operations,

develop guidelines and standards for efforts in the field,

provide support to personnel participating in peace operations,

promote the further development of UN cooperation with regional organisations on peace operations, for example through Training for Peace,

give priority to the Security Council resolutions on women, peace and security.

2.4 Peacebuilding and fragile states

Fragile states, with their weak government institutions, are more likely than other states to experience armed conflict. About 1.5 billion people live in conflict-affected countries in situations of fragility.

Many parts of the UN system are involved in strengthening conflict management at the national and local level, laying a foundation for long-term peace and development through political processes, safeguarding human rights, promoting reconciliation, economic development and the rule of law, and strengthening the health and education sectors. Usually the World Bank, individual countries, private contractors and large numbers of NGOs are also involved.

Figure 2.4 Elections are an important part of peacebuilding. Presidential elections in East Timor, 2012.

Source Photo: UN Photo/Bernardino Soares

2.4.1 The difficulties of peacebuilding

Peacebuilding depends primarily on internal political processes that are determined by political, economic and social factors, but the international community can still make a significant contribution. However, the international community’s approach has too often been uncoordinated, unplanned and short-term, and this, combined with the fact that fragile states often have limited capacity for strategic planning, setting priorities and coordinating international support, makes the task even more difficult.

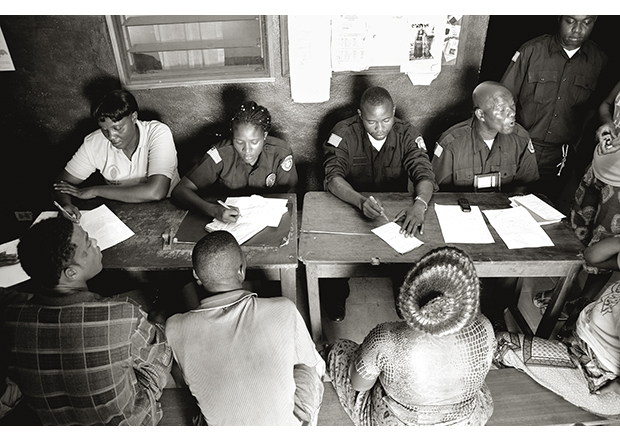

Figure 2.5 A public meeting in Sudan.

Source Photo: UN Photo/Fred Noy.

Norway has a strong bilateral and multilateral engagement in many of the states characterised as failed, for example Afghanistan, Haiti, Kenya, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan and South Sudan. Our engagement in states in situations of fragility and conflict is an important element of our efforts to promote human rights, development, humanitarian solutions, and peace and reconciliation. Fragile states are also a potential security threat because they lack the capacity to deal with threats that undermine their own and other states’ security, such as organised crime and terrorism. It is in Norway’s interest that problems in a distant country do not become global. The piracy off Somalia, with the threat it poses to Norwegian shipping, is an example of a situation where Norway has an obvious and direct interest in the stability and development of another country. In the case of fragile states, the UN has an advantage because of the breadth of the tools at its disposal, and we are therefore a strong supporter of UN efforts to assist these countries.

A well-functioning justice sector provides a sound framework that is essential to the reconstruction and development of a state. Here too, Norway should take a coherent approach and support the development of the justice sector. There is growing awareness of the importance of coordinated efforts in this area.

Figure 2.6 Police in Liberia undergoing training provided by the UN.

Source Photo: Thorodd Ommundsen

In 2010, 10 countries in a situation of fragility established a network called the g7+. The group originally consisted of Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Nepal, the Central African Republic, Chad, Sierra Leone, the Solomon Islands, South Sudan and East Timor. The aim is to exchange experience and work for a new paradigm for international engagement in countries in situations of conflict and fragility. The initiative is a good example of how these countries themselves are playing a leading role in resolving conflicts and reducing fragility, an approach that Norway supports. The group has now been expanded to include 19 countries.

In 2011, the g7+ launched the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States, a new model of cooperation between these countries and their international partners that has received widespread support. Under the New Deal the countries have committed themselves to a set of goals that includes fostering inclusive political settlements, increasing people’s access to justice, generating employment and providing accountable and fair service delivery. A total of 35 countries and six organisations have endorsed the New Deal, including Norway, the UN and the World Bank.

The multilateral institutions have an essential role to play in reducing the fragmentation of international assistance to fragile states. All the UN member states, including Norway, need to ensure that what they have defined as the UN’s task in peacebuilding is matched by the necessary resources and other framework conditions in other intergovernmental bodies.

The risks of involvement in fragile states are high. Many donor countries feel that peacebuilding efforts are compromised by corruption and waste. However, since the consequences of non-involvement may be even more serious, it is important to implement control and anti-corruption measures. Because of the high risks, responsibility for involvement in fragile states is often left to the UN. This poses a dilemma: the increasing focus on results in international assistance can lead to a reluctance to risk action that may be vital for development in the country concerned. Norway intends to demand results, while at the same time being willing to take risks.

2.4.2 The UN peacebuilding architecture

The UN has experienced major difficulties in coordinating both its own and other donors’ efforts in individual countries. In 2005 two bodies were established to strengthen the capacity of the UN system for strategic long-term planning: the Peacebuilding Commission and the Peacebuilding Fund. In addition, the Peacebuilding Support Office was set up to act as secretariat to the Peacebuilding Commission, administer the Peacebuilding Fund and support the Secretary-General's efforts to coordinate the UN System in its peacebuilding efforts. This group of bodies will be referred to below as the UN peacebuilding architecture.

Norway believes the Peacebuilding Commission has taken too little account of context at country level and maintained too little contact with the Security Council, other UN executive organs and the international financial institutions. At the same time we consider it positive that the Commission has helped to maintain a focus on countries that otherwise receive little attention, while the Fund has provided financing and political support in critical phases, strengthened coordination and fostered a coherent approach. We will seek to ensure that the UN peacebuilding architecture is further strengthened through better coordination, clearer priorities and more targeted efforts in the field.

Norway is working with other donors to ensure that while focusing on results, the Peacebuilding Fund is also willing to accept a degree of risk. A stronger Peacebuilding Commission, with close links to the Security Council, will hopefully provide the necessary umbrella for unifying UN engagement in peacebuilding.

Norway believes that in order to provide more effective support at country level, the member states must enable the UN to make more effective use of its tools for peacebuilding purposes. At present effective cooperation is being blocked by budget procedures, administrative procedures and limited mandates. We will support the Secretary-General in his efforts to take the necessary steps towards structural changes, and will mobilise support from other countries.

In Norway’s view the UN neither can nor should be responsible for all actions taken in fragile states. The Organisation needs to concentrate on the tasks at which it is best in each country. These will often include overall strategic functions, support for reform and capacity-building in public institutions, and coordinating international assistance. Working with the local population at grass roots level and implementing local projects is better left to the more qualified NGOs.

2.4.3 The right person in the right place at the right time

The UN is expected to carry out more and more peacekeeping and peacebuilding tasks. In recent years it has become clear that the UN system cannot possess either the competence or the capacity to cover all peacebuilding needs, and that it would benfit from involvement of other actors as a supplement. The challenges the UN is facing in this regard were discussed in a report by an advisory group appointed by the Secretary-General, the Guéhenno Report (2011).1 In autumn 2011, the Secretary-General produced the UN Review of Civilian Capacities, which details the capacities available for meeting the enormous need for personnel for international operations, building competence in the South, identifying and drawing on existing local capacity in fragile states and, not least, ensuring that expertise remains in the country after the peacebuilding team have left. The review also examines administrative procedures and bottlenecks that need to be addressed. Norway is providing political and financial support for the Secretary-General’s work in this area.

Figure 2.7 South Sudan.

We have long advocated the use of civilian capacities in peacebuilding, for example in the form of the Norwegian standby rosters NORCAP, NORDEM and the Crisis Response Pool (see Box 2.7). Several member states have shown an interest in our experience, and we are conducting a dialogue with a number of countries that wish to establish corresponding mechanisms. Norway and like-minded countries are supporting the efforts of the Secretary-General, but these are being hampered by the poor cooperation climate between other groups of member states. Norway considers the use of civilian capacities to be an important means of making UN efforts on the ground more effective, and will support the implementation of the recommendations in the Review of Civilian Capacities through our own policies and by mobilising support from other countries.

The Government will

strengthen the capacity of the multilateral institutions to assist national authorities in their peacebuilding and development efforts,

work for greater coordination of UN efforts in fragile states, and ensure that the Organisation works closely with other donors,

be a stable donor and significant contributor to the UN Peacekeeping Fund,

promote the use of external civilian capacity in peace operations and peacebuilding, for example through the standby rosters NORDEM and NORCAP,

strengthen cooperation between the UN system and the World Bank in fragile states.

2.5 Disarmament and non-proliferation

The multilateral nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation system has come under heavy pressure in recent years. In addition to the lack of progress on disarmament by the nuclear powers, there is a risk of proliferation by a several countries, primarily Iran and North Korea.

2.5.1 Non-proliferation, no progress – deadlocked negotiations

The Review Conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty in 2010 resulted in agreement on seeking the “peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons” and a detailed action plan for implementing the commitments related to nuclear disarmament and nuclear non-proliferation. However, little progress has been made towards these goals. Although nuclear weapons stockpiles have been considerably reduced since the end of the Cold War, there are no signs of any committed movement towards a world without nuclear weapons. On the contrary, a number of countries have indicated that they still consider their nuclear weapons to be of great importance for national security, and have comprehensive plans for upgrading them.

The established multilateral disarmament machinery seems to have ground to a standstill. One of the reasons for this is the requirement of consensus. During the Cold War it was easier to make consensus a requirement in multilateral disarmament forums because in many cases only two superpowers had to be taken into account. In today’s geopolitical reality, this requirement is an obstacle to multilateral disarmament and makes it possible for a handful of countries to maintain the status quo. Norway would like to see a fundamental change in the approach to disarmament and non-proliferation and greater attention being paid to the consequences of lack of progress.

Textbox 2.7 Norwegian civilian contributions to peace operations and peacebuilding

Since the 1990s Norway has played an important role in the efforts to build capacity at national and international level. Today we contribute a large number of civilian experts to international crisis management, and our standby rosters can call on broad expertise and many nationalities, including personnel from countries in the South, who can be deployed at short notice.

Since 1991, NORCAP has been administered by the Norwegian Refugee Council. NORCAP is the world’s most frequently used standby roster, and at any one time around 160 individuals are deployed in various parts of the world. The Council also administers personnel from other countries seconded to standby rosters, such as the UN ProCap (protection capacity), GenCap (gender capacity) and MSU (Mediation Support Unit).

NORDEM (Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights) was established in 1993 by the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights, and deploys some 80 personnel a year.

Since 1989 the Ministry of Justice and Public Security has deployed civilian police personnel through the Police Directorate to operations under the UN, the EU and the OSCE, and to bilateral projects. As of January 2012, 54 personnel have been deployed.

The Crisis Response Pool, under the auspices of the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, was established in 2003 and consists of personnel from the prosecuting authority, the courts and the correctional services, together with a number of defence lawyers. As of January 2012, 14 persons have been deployed.

Since the 1990s, the Directorate for Civil Protection and Emergency Planning has administered two operative units (the Norwegian Support Team and Norwegian UNDAC Support), consisting mainly of personnel from the Norwegian Civil Defence, to provide support to aid agency personnel working in international disaster areas.

In recent years the problems and challenges of work in multilateral forums have led countries that wish to obtain results to choose other processes and arenas, for example unilateral and bilateral solutions. The Mine Ban Convention and the Convention on Cluster Munitions were negotiated in separate processes, although the UN is also involved, since the General Assembly has approved the conventions and UN organisations are involved in their implementation.

2.5.2 Reform of the intergovernmental machinery

Norway would like to see a strong UN in the area of disarmament. We are working for the revitalisation of the First Committee of the General Assembly, which deals with disarmament, on the basis of the existing bodies. The current proposals include shorter sessions, the adoption of fewer and more operative resolutions and other measures to enhance the Committee’s role as a forum for dialogue and the exchange of views. In the Conference on Disarmament (CD), Norway has proposed that the consensus requirement should be dropped and that the CD should be open to all UN member states that wish to participate and to civil society. With regard to the United Nations Disarmament Commission (UNDC), Norway has been actively working for shorter sessions and a more concise agenda, and has proposed dropping the requirement of consensus on the outcome document. However, none of these proposals have been adopted.

The poor prospects for reform of the existing disarmament machinery make it necessary to consider other alternatives. One possibility would be to establish disarmament negotiations under a mandate from the General Assembly and with the Assembly’s rules of procedure, which do not include a consensus requirement. Norway is considering putting forward such a proposal together with like-minded countries if it is likely to receive constructive support in the General Assembly.

There are also other possibilities less closely linked with the UN system. Norway considers that the primary concern must be that the chosen approach should yield practical results. As long as the existing multilateral disarmament machinery is dysfunctional, we will continue to work together with like-minded countries, the UN, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, and civil society on finding alternative approaches in the area of disarmament, as we did in the case of the Mine Ban Convention and the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

In Norway’s view, NATO’s work in this field should reflect global political trends, and Norway has played a leading role in putting disarmament on NATO’s agenda. The goal of a world without nuclear weapons is now part of the Alliance’s new 2010 Strategic Concept. The Alliance concluded its Defence and Deterrence Posture Review at the NATO Summit in Chicago in 2012, at which negative security assurances were mentioned for the first time in a NATO context. Agreement was also reached on promoting transparency and confidence-building in relations with Russia on short-range nuclear weapons, a category of nuclear weapons that so far is not covered by any disarmament agreement.

In the disarmament field generally, Norway will continue to focus particularly on humanitarian aspects. We will work together with other member states and organisations to promote the development of norms and instruments to regulate and /or prohibit the use of weapons and types of weapons with unacceptable humanitarian consequences.

Norway will host an international conference in March 2013 on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons detonations, both deliberate and accidental, and the question of a credible, effective emergency response. The conference is designed to engage a broader set of actors than have been involved in disarmament issues in recent years, and will involve the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the Red Cross and other humanitarian organisations. One of the aims of the conference is to raise awareness that the consequences of the use of nuclear weapons for the climate and for health and food production will be global, and will hit the poorest countries especially hard. This initiative has already attracted a great deal of attention.

The Government will

continue to work for a comprehensive reform of the UN's disarmament bodies, including a weakening of the requirement of consensus in multilateral negotiation processes in this policy area,

seek to ensure that civil society and other interested parties are able to participate in international disarmament processes,

strengthen the legal obligations relating to international instruments and draw particular attention in disarmament contexts to the humanitarian and development consequences of the use of nuclear weapons,

work for a world without nuclear weapons,

put the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons use on the international agenda.

2.6 UN efforts to address emerging threats

Terrorism and transnational organised crime are serious threats to international peace and security. The fight against terrorism is high on the international agenda, especially since the 2001attacks on New York and Washington. However, the threat posed by transnational organised crime has only recently attracted international attention. Both these threats directly affect Norwegian interests.

Textbox 2.8 Ban on cluster munitions

Following the failure of the states parties to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) to agree on starting an international process to address the humanitarian problems caused by cluster munitions, the Norwegian Government invited the UN, the Red Cross movement and other humanitarian organisations to an international conference in Oslo in 2006. Norway thereby took a leading role in the process that resulted in the Convention on Cluster Munitions, which bans the use, stockpiling, production and transfer of these weapons. The process had also been driven forward by humanitarian and human rights organisations, which had worked for many years to put the issue on the agenda. The Secretary-General and a number of UN field-based organisations took an active part in the process, which rapidly gained the support of a large number of states the world over. The ban includes all types of cluster munitions, and is generally agreed to have set a new standard in international humanitarian law. The convention was opened for signature in Oslo in December 2008, entered into force in August 2010 and has so far been ratified by 111 countries. It also has the full support of the international community in the form of the UN, humanitarian and human rights organisations, and the International Red Cross movement. In the course of the first two years since the convention entered into force, large numbers of cluster munitions have been destroyed, large areas of land are being cleared by the states parties and the norm that cluster munitions are an unacceptable weapon has been strengthened, even among states that are not parties to the convention. This shows that it is possible to achieve good, concrete results in disarmament issues when different actors cooperate on achieving a common goal and keep the focus on humanitarian realities in the field.

2.6.1 Combating international terrorism

Counter-terrorism is on the agenda of both the General Assembly and the Security Council. Subsidiary bodies have been established in both forums to address the problem, and practical action against terrorism is on the agenda of many UN specialised agencies. A series of instruments for combating terrorism that are binding under international law have been adopted. They cover a broad field, including suppression of terrorism financing and bombing, access to nuclear material, and prevention of hijacking.

Norway’s efforts against terrorism are based on respect for human rights and the rule of law. The relevant international instruments are an important part of the long-term work in this field, and are used as a tool to prevent and combat terrorism. The UN has a special responsibility for coordinating the global efforts against terrorism, and Norway believes that the UN’s role should be strengthened in order to ensure that international efforts are collectively and individually followed up by all the countries of the world. In our view a coherent, long-term approach, with a focus on prevention, is the most effective means of combating international terrorism. Strengthening the role of the UN would unite and coordinate international efforts in the short and long term.

The UN’s Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy represents a major step in the international efforts to combat terrorism, and is at the core of Norway’s engagement in the UN. The strategy reduces international tensions in counter-terrorism efforts because it takes a broad approach and because it has been adopted by consensus in the General Assembly. Norway supports the strategy both politically and financially, for example through our support for the efforts of the Counter-Terrorism Implementation Task Force to assist member states to implement the strategy. We will continue to support the efforts to strengthen UN counter-terrorism activities.

Textbox 2.9 Transnational organised crime in the fishing industry

The Norwegian National Advisory Group against Organised IUU Fishing was established in 2009 specifically to combat organised crime related to IUU fishing (as discussed in the white paper on the fight against organised crime (Meld. St. 7 (2010–2011)). It has proved difficult to mobilise global cooperation on action in this area due to the fact that there is little international awareness that fisheries crime may also be perpetrated by transnational organised criminal groups.

Acting on a Norwegian initiative and with Norwegian financial support, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) performed a study of transnational organised crime in the fishing industry that was published in April 2011. The Norwegian National Advisory Group against Organized IUU Fishing was consulted, and made a valuable contribution. The study identified a range of crimes involving the global fishing industry, such as the use of fishing vessels for drug and weapons smuggling and the trafficking of persons for the purpose of forced labour on illegal fishing vessels. It also showed the global, transnational nature of crimes in the fishing industry. As a result of the study, the UN Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice adopted a resolution on combating the problem of transnational organised crime committed at sea at its 20th session in 2011. An increasing number of international and regional bodies such as Interpol, ASEAN and the OECD are now becoming concerned about the issue, and in November 2011 the European Parliament gave its full support to the study recommendations in the form of a resolution on combating illegal fishing at the global level.

2.6.2 Transnational organised crime

Transnational organised crime, which involves drugs, trafficking in weapons, piracy, human trafficking and environmental crime, is a growing problem. It directly affects security and in many countries threatens to undermine stability and development. Criminals are buying immunity from the authorities and using ruthless methods to corner the market and secure market power. The profits of drug smuggling and other transnational organised crime have been estimated by the UN to be worth USD 870 billion in 2009. This is about twice the size of Norway’s GDP. Less than 1 % of this is seized. Digital crime is perhaps the most widespread form of transnational crime and requires a correspondingly global response.

Transnational organised crime directly affects Norway, and has substantial consequences for countries where we are working for security and development. Piracy off the coast of Somalia is an example, and Norway has funded two experts from the Correctional Services to advise on execution of pirates’ sentences.

Norwegian companies are dependent on the existence of a functioning police force and an independent judicial system in the host country to provide the predictability they need in order to operate abroad. The existence of criminal organisations with a global field of operation also means that the Norwegian police authorities have to depend on global cooperation between the different countries’ police and judicial authorities.

The UN conventions against transnational organized crime, the three protocols on human trafficking, human smuggling and firearms, and the two UN Conventions against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and against Corruption, form the framework for intergovernmental work in the UN in the field of organised crime.

Textbox 2.10 Combating piracy off Somalia

The financial flows generated by piracy are destabilising Somalia even further. The Security Council established the Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia (CGPCS) to coordinate the international efforts to suppress piracy in these waters. The responsibility for coordination does not lie with the UN but with the CGPCS, although the latter reports on progress to the Security Council. The CGPCS is a coalition of volunteers, and has no secretariat and no employees. Norway chaired the group in the first half of 2010. The UN also manages the Trust Fund that provides financial support to the CGPCS, which was established during Norway’s chairmanship. There have been a number of debates in the Security Council on the issue of Somali piracy, particularly the question of prosecuting arrested pirates. The board of the Trust Fund is chaired by the Department of Political Affairs and the fund is managed by UNODC. However, it has been decided that UNODC will no longer have this role because it is also the largest recipient of project support from the fund, primarily for projects in the justice sector in the region dealing with prosecution of pirates.

Norway believes that the development of an international legal order, effective cross-border and cross-regional cooperation, strong justice and security institutions, and intensive anti-corruption efforts play an important role in the fight against transnational organised crime. Regional and national ownership are essential to success. So far the justice and security institutions involved in crime prevention have mainly focused on national conditions, and cooperation between countries and regions has been limited. The efforts need to be linked far more closely with the international agenda for development, security and the rule of law, and UN organisations need to cooperate more closely with international police organisations. Important steps would be to strengthen national Interpol offices in conflict areas and to ensure the effectiveness of global efforts to combat money laundering.

Criminal law and the fight against crime have been on the UN agenda for a long time. Transnational organised crime is one of the greatest global challenges the world is facing, and has to be combated at the global level. In Norway’s view the UN’s normative and operational tools place it in a unique position to raise transnational crime prevention to the global level and drive cooperation mechanisms and common approaches. A recent step in the right direction was the inclusion of this form of crime as a separate item on the Secretary-General’s new five-year action agenda. Norway wishes to see the development of a global strategy against transnational organised crime and better coordination of UN efforts in this area, and will support the Secretary-General on this.

The Government will

support the implementation of the UN's Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy,

defend human rights and the principles of the rule of law in the fight against terrorism,

support UN efforts to combat transnational organised crime, including the work of UNODC,

support the development of a global strategy against transnational organised crime, including the development of national and regional strategies,

seek to ensure that the work against illicit capital flows generated by organised crime is given higher priority by the UN,

give priority in its work in the UN to the fight against corruption, illicit traffic in drugs, and transnational organised crime, including human trafficking.