4 A sustainable world: the United Nations and economic, social, humanitarian and environmental issues

The UN’s work in the economic and social area covers a broad range of issues – from finding joint solutions to climate change issues and global environmental problems, use of resources, and health, to development cooperation, where poverty reduction is the primary objective. These are complex global problems that are becoming increasingly interlinked. The strength of the UN lies in its dual role as an arena for intergovernmental debate and decision-making and its operational role. As an intergovernmental arena, the UN provides guidelines for international cooperation on global problems and challenges and for achieving results at country level.

It is in Norway’s interest to be involved in the development, regulation, financing and implementation of global solutions to global problems, for example in areas such as food security, environmental issues and climate change. There is a close link between our national political interests and global efforts in the same areas, and it is important for us to have an international arena where we can promote our views and interests.

Norway makes large contributions to the UN’s development and humanitarian activities. We consider it essential that the UN organisations should have as their overarching objectives poverty reduction and a rights-based approach should be overarching objectives that ensure involvement of vulnerable groups such as minorities, persons with disabilities, and children and young people. Mainstreaming of women’s rights and gender equality, as described in the white paper On Equal Terms: Women’s Rights and Gender Equality in International Development Policy (Report No. 11 (2007–2008) to the Storting), and of environmental considerations, as set out in the white paper Towards Greener Development (Report No. 14 (2010–2011) to the Storting), are cross-cutting priorities in our cooperation with UN organisations.

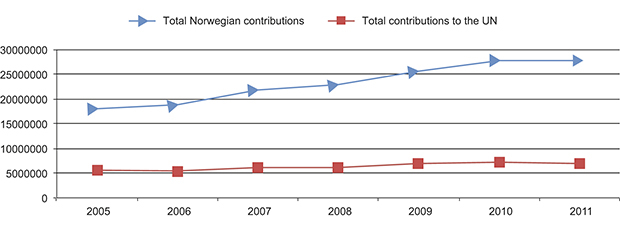

Figure 4.1 Total Norwegian development assistance, total contributions to the UN and trends in the proportion of total Norwegian contributions to the UN, NOK thousands.

Source Norad’s statistics database

The overall context and framework conditions governing the UN’s activities in the economic and social area are changing. Some countries are experiencing strong economic growth and have moved from low-income to middle-income status. The Global South is an increasingly differentiated group of countries with different needs and priorities in relation to the UN. However, economic growth has not been accompanied by more equitable distribution, and a growing number of poor people now live in middle-income countries. The recognition that development aid is only one factor in economic and social development has caused a shift in focus towards other sources of funding and other partnerships. The UN in its role as political arena, together with its operational developmen t and humanitarian organisations, will have to adapt to these new conditions.

Figure 4.2 The High-level Panel at the UN Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio (Rio+20), 21 June 2012.

Source Photo: UN Photo/Erskinder Debebe

4.1 The UN and the political agenda

Norway makes use of the various UN arenas to promote the development of binding international guidelines, to influence the international agenda and to seek international support for Norwegian perspectives, ideals and objectives. Our success in these efforts depends on the effectiveness of the alliances we form.

4.1.1 The UN’s role in sustainable development – the way forward after Rio

Promoting sustainable development is a key objective of the UN and of Norway’s UN policy. The growing pressure on the world’s natural resources and the growing recognition of the links between environmental and development issues call for a policy that integrates the economic, social and environmental dimensions. Norway is committed to taking a lead in enhancing the UN’s engagement in environment and development. This means that we will focus especially on strategies that combine the objectives in these areas.

An example of an integrated strategy where Norway is a prime mover is the efforts under the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) to strengthen global fisheries management. Improving fisheries management will have positive effects in the environmental, economic and social sectors: it will reduce overexploitation (environmental), and provide a more lasting source of income (economic) and stable access to nutritious marine protein (social).

The agreement reached in Rio+20 on developing Sustainable Development Goals – specific goals for sustainable development based on the model of the Millennium Development Goals – was considered by Norway to be an important result. The Sustainable Development Goals are intended to mainstream the three dimensions of sustainable development: social, economic and environmental, and will apply to all countries. An intergovernmental Open Working Group established by the General Assembly will develop a proposal for the Sustainable Development Goals, and the Government intends to play an active role in its deliberations.

Norway considers it important that the Rio outcome document recognises that sustainable development hinges on women’s participation on equal terms in political and economic decision processes. The use of gender-sensitive statistics was a Norwegian priority that was successfully incorporated. Such statistics are essential for measuring how far political commitments are being implemented in practice and for directing resources to areas where they are needed. The affirmation of women’s equal rights to property, inheritance and other resources provides a good basis for eliminating discriminatory practices at country level, which is a high priority for the Government.

It is important for the Government's Energy+ initiative that the Secretary-General's initiative on Sustainable Energy for All (SE4All) was also included in the Rio outcome document. The objectives of SE4All are to ensure universal access to modern energy services, to double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency, and to double the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix by 2030. The Government will give priority to following up the initiative in the UN system and coordinating these efforts with our own Energy+ initiative.

The Rio outcome document states that access to safe, sufficient and nutritious food is a human right, and emphasises the need to revitalise the agricultural and rural development sectors and reduce food loss and waste. In future food production will depend on adaptation to climate change and sustainable management of biodiversity, including ecosystem services. The outcome document recognises the key contribution of the Committee on World Food Security (CFS), which has had a stronger role to play since the reform of FAO. The CFS is now the main body for coordinating the work on food security, and the Government will support the committee in this role. We will make use of our prominent role as seafood producer and steward of marine resources in international negotiations, including those in the CFS.

Textbox 4.1 Climate change

In Norway’s view, the central framework for international climate cooperation is the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (the Climate Change Convention). The convention’s ultimate objective is to achieve stabilisation of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Norway attaches decisive importance to the establishment of a binding international regime under the Climate Change Convention. In the white paper on Norwegian climate policy (Report No. 21 (2011–2012) to the Storting), the Government stated that it will promote a broad, ambitious climate agreement that sets specific targets for emissions reductions that apply to both developed and major developing countries and that are in accordance with the target of limiting the average rise in the global mean temperature to no more than 2 °C above the pre-industrial level. Certain large developing countries are responsible for the fastest rise in greenhouse gas emissions and for an increasing share of global greenhouse gas emissions, and it will be essential to limit their emissions if the target is to be achieved.

Even though greenhouse gas emissions have been somewhat reduced as a result of the Climate Change Convention and the Kyoto Protocol, total global emissions continue to rise, and it will be very difficult to achieve the two-degree target. Although the poorest and least developed countries have the least responsibility for the problem, they are the most seriously affected by the consequences. International cooperation on adaptation to climate change, preventing climate-related disasters and reducing greenhouse gas emissions is therefore essential.

Green economy in the context of sustainable development and poverty eradication was one of the two main themes of the 2012 Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio. “Green economy” means an economy that, while promoting all the economic objectives (jobs, prosperity, social goods etc.), involves a smaller risk of environmental damage and ecological scarcities. The Rio conference showed that there is no common understanding of what a green economy involves, despite the affirmation in the outcome document that it is a tool for achieving sustainable development. Mechanisms were established at the Rio conference to assist countries, on request, to implement green development strategies. Norway supported the proposal for broader measures of progress that complement gross domestic product by including natural capital and the well-being of the population, as well as strengthening cooperation on promoting sustainability reporting by businesses. Norway is well ahead in these areas, and the Government will participate in further international efforts with this aim.

Norway considers it very positive that the outcome document emphasised that governments need to finance sustainable development by mobilising national financing and finding innovative sources of finance (in addition to private and public investment and development aid). At the conference we took the initiative to include the need to combat corruption and illicit financial flows in the text in addition to financing measures. We are also pleased that the conference encouraged countries to adhere to and implement the UN Convention against Corruption. The developing countries advocated the establishment of a new financing mechanism, but there was no agreement on this issue. However, as a compromise it was agreed to establish an intergovernmental process to assess financing needs and propose an effective sustainable development financing strategy to facilitate the mobilisation of resources. The process will be implemented by an intergovernmental committee of 30 experts nominated by regional groups, and the Government will follow the committee’s work.

The other main theme of the conference was the institutional framework for sustainable development. The discussions focused mainly on the need for two reforms of the UN system: the replacement of the Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) by a more effective body, and the strengthening or upgrading of UNEP.

It was agreed to replace the CSD with a new High-Level political forum on sustainable development and that processes will be initiated in the General Assembly to decide on its structure, mandate and functions. The Government will seek to ensure that the forum has more effective tools at its disposal than the CSD has, such as universal periodic reviews, and that it is given a central role in implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals and other key proposals in the Rio outcome document.

The Rio conference confirmed the need to strengthen the international environmental governance system. It was agreed at the conference that UNEP should be strengthened and upgraded in accordance with its role as the leading global environmental authority, among other things by making membership of its governing body universal. However, it was not possible to reach agreement on the proposal to upgrade the organisation to a specialised agency, which is the Government’s long-term objective. Norway will continue to support the efforts to strengthen UNEP, in the short term particularly by strengthening the financing and supporting the establishment of a more efficient governance structure.

4.1.2 A common post-2015 development agenda

The UN Millennium Declaration and the eight Millennium Development Goals have dominated international development efforts for the last 12 years. The MDGs have served as guidelines for Norwegian and international development policy, and formed the basis of strong, purposeful, individual-centred efforts to improve health and education and promote gender equality.

The concrete and straightforward MDGs have a strong mobilising force, and focus on results and efficiency. However, they do not really address the structural causes of poverty. Countries at war and in conflict, and marked by widespread discrimination, have made the least progress. Today, 70 % of children who do not attend school live in conflict areas, and there is little likelihood that they will be able to go to school until the conflict is resolved. Other areas that are not covered by the MDGs are the widespread illegal capital flows and the theft of natural resources in developing countries.

The Government will seek to ensure that the post-2015 development agenda takes greater account of the structural causes of poverty. The new goals must reflect the fact that more effective measures against poverty and better access to health and education services are closely linked with a greater capacity for economic development and growth that takes account of environmental and social considerations and equitable distribution. This means that measures to combat climate change, environmental degradation and the growing pressure on natural resources, together with the principles of anti-discrimination and gender equality, conflict resolution and respect for human rights, should be factored into the development agenda.

There is broad agreement that the new goals for the post-2015 development agenda should be as specific and straightforward as the current goals, and with the same capacity for mobilising the international community. Norway believes that several of the MDGs, such as those for the health and education sectors, should be continued, if necessary with adjustments. For example, much progress has been made on access to primary schooling since 2000, but the focus has been on quantifiable targets. Fresh, long-term investment in relevant quality education for individuals that will also benefit society is what is needed to combat poverty in both the least developed and the middle-income countries. The poorest countries should be assisted to develop their higher education systems, especially teacher training, so that they can draw up systems and curriculums that meet their needs. UNESCO can provide valuable input in this respect through its institutes for curriculum development, educational planning and statistics.

The new development goals must also take into account that 70 % of the world’s poor live in middle-income countries. The gap between rich and poor in these countries is widening rapidly, and at the same time many traditional donor countries are suffering from a serious economic recession. This raises new questions about the roles of donors, recipients and national wealth distribution polices. A new global development policy agenda should reflect these issues.

There is growing agreement that, like the proposed the Sustainable Development Goals, the goals of the new agenda should be directed at all countries, not only those in the South. The Government will seek to ensure that after 2015 there will be one set of goals to which all countries are committed.

4.1.3 The links between national and global policy

The UN is important to Norway as a global forum for addressing challenges that need to be dealt with internationally. The advantage of the UN lies in its importance as a global norm-setter. The Government considers that detailed solutions to problems, and their implementation, should be left to the regional and national levels. A good example is the Law of the Sea and fisheries, where the UN sets out the general, global rules, which are then adjusted to regional and national needs.

The UN also has an important role as a source of knowledge and information, which is available to all countries at the same time. Knowledge and research are also necessary for following norms and rules. For example, research and underlying data are a prerequisite for sustainable management of natural resources. Thus the Nansen programme – a collaboration between FAO and Norway on surveying and monitoring of fisheries resources and education and training, both bilaterally and through FAO – makes an important contribution to institution-building and sustainable fisheries management in selected countries.

Achieving global targets for food security, nutrition and sustainable fisheries management, and for reducing loss of biodiversity, depends on fundamental scientific knowledge and a sound management regime. The UN needs to develop closer cooperation with scientific institutions to obtain sound knowledge on which to base policy development. Problems relating to environment and climate change, poverty and food security are often inextricably linked, and require a coherent approach and good coordination within the UN system.

There is a growing gap between the number of international commitments and the member states’ capacity to put them into practice. The effectiveness and relevance of the UN depend not only on what the member states can agree on, and what importance other member states attach to UN decisions, but also on the member states’ capacity to implement their international commitments. The Government therefore considers that more emphasis should be given to how to ensure compliance with obligations at country level. UN funds, programmes and specialised agencies play a significant role in capacity- and institution-building. Norway will take the initiative to ensure that performance-based frameworks and evaluations do more to document the results of normative work at country level.

Expertise and patience are two of the prerequisites for gaining acceptance for our views in the UN. The clearer our position, the greater our influence. Our influence is further increased by the fact that we have a predictable voice across all relevant forums. This is particularly important for ensuring that issues we consider to be cross-cutting, such as human rights, women’s rights and gender equality, together with environmental considerations, are taken into account. In the Government’s view, a coherent and predictable UN policy will strengthen Norway’s influence in the UN. Chapters 5 and 6 describe the elements of such a policy.

The Government will

give priority to the UN’s efforts to promote sustainable development with a view to integrating the environmental, economic and social dimensions,

seek to strengthen UNEP in the short term and work for the establishment of a World Environment Organisation in the long term,

seek to ensure that the new forum on sustainable development is effective,

give the global challenges of urbanisation more prominence and consider increasing Norwegian multilateral aid to the prevention and upgrading of slum areas,

strengthen UN efforts in the health sector,

strengthen UN efforts in the education sector,

work for new, concrete post-2015 development goals that reflect current needs and realities, and address the structural causes of poverty,

promote the development of global sustainable development goals,

make active efforts to strengthen the UN’s role as a knowledge organisation for improving the management of natural resources and ecosystem services,

Be proactive in strengthening and further developing global work for food security through the UN.

4.2 Development cooperation in a state of change

The framework conditions for development cooperation are changing. Development aid is playing a diminishing role in funding development, and the growth in the number of middle-income countries without a corresponding reduction in poverty has drawn attention to the issue of equitable distribution at the national level. New actors and forms of cooperation are becoming more important. All these factors create both opportunities and challenges. The UN needs to adapt to this new situation and enter into new partnerships.

Norway will take part in discussions between interested member states across regional groups on the need to strengthen the governance structures for UN development and humanitarian activities. Strengthening the whole UN as a forum and platform for development policy dialogue and agenda-setting will also be discussed. The existing cooperation between like-minded countries such as the Nordic Plus (the Nordic countries, Ireland, the UK and the Netherlands), and the already established cooperation with countries in the South are a good foundation for these efforts. If the political dialogue in the new development architecture takes place within a UN framework, this could lead to fresh political room for manoeuvre and new operational roles. One of Norway’s main objectives is to shift the focus towards the role of national policy in development and the individual countries’ own responsibilities in this respect.

4.2.1 Financing for development

Financing is a central underlying issue in discussions on common goals and strategies, from climate negotiations to reform of UN development efforts.

Norway will seek to ensure that the debate on financing for development in the UN focuses even more strongly on financing sources other than development aid. The developing countries’ mobilisation of their own resources through taxation, preventing illicit capital flows, and innovative financing, and the follow-up role of UN organisations, have a large part to play. Norway’s experience that gender equality and women’s participation are essential to economic growth and development is a key element of our approach to these issues.

Textbox 4.2 Innovative financing

In the climate change negotiations, Norway is a champion of the greater use of innovative financing. Prime Minister Stoltenberg co-chaired the High-Level Advisory Group on Climate Change Financing established by the Secretary-General, which produced recommendations on how USD 100 billion a year can be obtained for climate actions in developing countries. The Advisory Group’s report contained a number of innovative mechanisms for filling the financing gap, many of which Norway supports. The challenge here is to ensure broad international support.

The Government is working in cooperation with other countries on the introduction of a currency transaction levy to raise funding for global public goods, development and climate action. Before such a levy can be introduced, it has to win broad international support and be endorsed by influential countries. Norway attempted to have a reference to such a levy included in a General Assembly resolution, but without success.

The relevant UN organisations are able to make valuable contributions to the work on equitable distribution by analysing the relationship between economic growth and economic and social disparities. The analyses will enable UN country teams to advise the national authorities on how to formulate national polices that promote poverty reduction, more equitable distribution and greater stability. Norway can offer its experience of a distribution policy based on the Norwegian/Nordic welfare model, women’s participation in the labour market, tripartite cooperation and a taxation system that emphasises redistribution and efficient use of resources. In our work with the UN, we make active use of the lessons learned from programmes such as the new Tax for Development and Oil for Development programmes, and from our efforts to combat tax havens and illegal capital flows.

Textbox 4.3 The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

UNCTAD has been in crisis for several years, and has been unable to deliver satisfactorily on its mandate. The UN Joint Inspection Unit reviewed the organisation and produced a very critical report on its management. The report is currently under consideration by the board of UNCTAD. Norway has stated that it is prepared to assist UNCTAD to make the necessary changes.

The Doha mandate adopted at UNCTAD XIII affirmed UNCTAD’s core activities in the area of trade and development. Norway considers it important to ensure that UNCTAD continues to work with debt management issues, and we have financed an UNCTAD project on Draft Principles on Promoting Responsible Sovereign Lending and Borrowing. The organisation’s work complements that of the World Bank and the IMF in the field of debt management and financial development. Another priority area for Norway in the Doha negotiations was the integration of women’s rights and gender equality in UNCTAD’s activities. In this area the wording of the mandate was stronger than in previous mandates.

Norway will seek to ensure that UNCTAD’s work is perceived as relevant by the WTO and the World Bank.

4.2.2 Partnerships

Changes in the relations between states, the market and individuals pave the way for cooperation between a range of actors from the private sector, civil society, and research and other academic communities. The UN system needs to find new, innovative ways of involving these actors.

The UN system can facilitate forms of cooperation such as South–South and triangular cooperation. The Government considers that the UN organisations should engage in dialogue with new actors and in cooperation at country level.

Norway has been among the leading advocates of linking the private sector, global funds and philanthropists with UN processes, especially through the Clean Energy for Development initiative and in the health sector. The Committee on World Food Security (CFS) is an example of the involvement of non-state actors. Norway regards this approach as extremely positive, and will seek to ensure that existing structures facilitate participation by non-state actors. However, it is important that this does not lead to fragmentation and extra work.

Norway has been a strong advocate for access by civil society representatives to UN meetings, processes and conferences. We have a tradition of participation by civil society, including representatives of youth groups, in our delegations to UN meetings. The Government will standardise the practice of participation by such actors in Norwegian delegations to UN meetings, which varies today from forum to forum and from one ministry to another.

There is a special need to improve young people’s participation in the UN on a free and independent basis. The Government will support Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon’s initiative to appoint a Special Adviser for Youth, who will be responsible for drawing up an overall plan for the UN’s work for youth in the years ahead. The Government will provide funding for the establishment of a UN youth forum on the lines of for example the International Indigenous Forum. Here young people and their organisations will be able to influence UN policy and engage in a dialogue with member states.

The Government will

strengthen the UN’s role as a global political forum for economic and social issues, and work to make ECOSOC stronger and more effective,

strengthen the efforts of the UN, the World Bank and other multinational development institutions to promote equitable distribution between and within countries,

seek to introduce global levies that limit the negative effects of globalisation and create global redistribution mechanisms,

promote the introduction of new global financing mechanisms for promoting redistribution and funding for global public goods,

seek to ensure that efforts are made in the UN to combat tax havens, illegal capital flows and financial secrecy,

advocate that the UN puts national resource mobilisation on the agenda,

give priority to furthering support for the UNCTAD Draft Principles on Promoting Responsible Sovereign Lending and Borrowing,

support access by civil society to UN meetings, processes and conferences,

review and standardise practice and support schemes for participation by civil society in Norwegian delegations,

support the Secretary-General’s work for youth and his initiative to appoint a Special Adviser for Youth, and work for the establishment of a UN forum for youth on the lines of the International Indigenous Forum.

4.3 The UN as a driver of development

With their broad range of different and sometimes unique mandates, the UN organisations are in a good position to promote change in developing countries. In the white paper Climate, Conflict and Capital (Report No. 13 (2008–2009) to the Storting), the Government emphasised that health and education, governance, agriculture and general capacity and institution-building are particularly appropriate sectors for Norwegian multilateral support. The Government is also highlighting areas of high political priority such as climate change, Norway’s Climate and Forest Initiative, peace initiatives, gender equality, management of non-renewable resources, and combating illicit financial flows through our work in the multilateral organisations.

However, the UN’s operational organisations are still facing the problems of fragmentation and poor coordination that are causing the UN development system to deliver less than it is capable of. As one of the largest contributors to UN organisations and a champion of a UN-based global platform, Norway has played an active role as supporter and driver of reform.

4.3.1 From words to action – the UN’s role at country level

The Government considers that the most important consequence for the UN of changes in the development system will be that the UN organisations will focus less on projects and more on providing expert advice as well as capacity- and institution-building. It is important to identify areas that should not be the responsibility of the UN and areas where other actors would be more suitable cooperation partners for Norway.

Norway has given priority to the work of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) on good governance, environment and sustainable development, for example its efforts to ensure that environmental considerations are mainstreamed into the various countries’ poverty reduction strategies. In the Government’s view, UNDP has achieved varying results at country level and the organisation has a tendency to spread its efforts too thinly. In our dialogue with UNDP, we are therefore stressing the need for better performance and more concentration on important areas in countries where performance has not been satisfactory.

Figure 4.3 Azerbaijan.

Source Photo: UNICEF/Giacomo Pirozzi

UNICEF’s primary task is to safeguard children’s rights under the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Education is one of the organisation’s focus areas, and Norway has for many years been cooperating with UNICEF on protecting the right of every child to receive a quality education. In 2010, Norway provided sufficient support through UNICEF for 500 000 children to attend school (Norad’s Result Report 2010).

Textbox 4.4 UN-REDD – environment and development, innovation, and Norwegian influence

The United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (UN-REDD) is a collaborative effort under which FAO, UNEP, UNDP and the World Bank are assisting developing countries to reduce forest degradation and emissions from deforestation. The programme was established in 2008 following a Norwegian initiative, and is funded through the Norwegian Government’s International Climate and Forest Initiative. Currently it has five donors: the EU, Denmark, Japan, Spain and Norway.

UN-REDD is an example of how earmarking puts specific themes with high priority, such as climate change and deforestation, on the UN agenda. For example, in 2012 the more comprehensive programme REDD+ was mentioned as a priority area in the Secretary-General’s Five-year Action Agenda. Norway succeeded in having certain of our interests, such as gender equality and governance, included in the UN-REDD programme. This is a good example of how we can contribute to innovation and ensure that the UN acts and operates as One UN at both country and global level.

The health sector is an example of an area where there is close cooperation between the actors involved. Norway will continue to advocate innovation in this area through cooperation with partners consisting of states, civil society and the business sector.

The UN and the World Bank both have a responsibility for improving coordination at country level, and the cooperation between these organisations needs to be strengthened. In the Government’s view a permanent division of work is not always either appropriate or desirable, since who does what depends on the situation in the individual country. However, this does not mean that the respective governing bodies should not send clear signals and provide incentives for cooperation. The Government will encourage greater use of joint risk assessment at the country level based on the tool developed jointly by the UN and the World Bank, and advocate that the World Bank participates to a greater extent in joint planning and cooperation on implementation. This is particularly important for macroeconomic policy and budget cooperation, and in order to link short-term engagement with more long-term sustainable development. The Government will also work for further decentralisation of decision-making authority and for reform incentives enabling the UN and the World Bank to collaborate at country level. These efforts require closer cooperation between the two organisations at intergovernmental, headquarters and above all country level.

The UN system has shown that it is capable of adaptation and innovation. However, the UN’s functions, financing, capacity, partnerships and structures, including governance structures, need to be reviewed if the Organisation is to adapt more effectively to the new framework conditions and the involvement of new actors, and if the UN system is to be capable of dealing with new and existing challenges. The Government will work together with other member states to ensure that these issues are debated in the period up to 2015.

4.3.2 A more effective UN: Delivering as One

The Government believes that reform is crucial to ensuring the continued relevance and greater effectiveness of UN organisations at country level. The challenges identified in the evaluations of the UN reform/Delivering as One must be addressed. The following are weaknesses and focus areas that have been identified so far.

Reform requires good leadership. The Secretary-General and the heads of the UN organisations must send a clear message and provide incentives for cooperation at country level. In technical issues, the organisation with the relevant expertise should speak on behalf of the UN system.

The evaluations have shown that bottlenecks in cooperation efforts must be dealt with at headquarters level, and that there is a need for further harmonisation and greater efficiency. Some progress has been made, for example through the harmonisation of procurement rules, which makes it possible to undertake large-scale procurement and has the advantage of economies of scale, but a greater number of administrative tasks could be addressed jointly. The existence of different reporting requirements and planning processes results in extra work and is an obstacle to cooperation. Different ICT systems are getting in the way of information-sharing. Security considerations have in many cases stood in the way of co-location in One UN House.

The central funding mechanism (the Expanded Funding Window) and the One UN Funds at country level are so far the most important tools for advancing the reform. The Government will therefore seek to strengthen the donor base for the Delivering as One programme, both centrally and at country level. In order to mobilise more donors it may be necessary to introduce some degree of earmarking for strategic goals in the Delivering as One programme in addition to general contributions.

Autumn 2012 marked a crossroads in the reform process. The programme countries themselves say there is no way back. In the action plan for his second term of office, the Secretary-General is advocating a second-generation One UN. The Government supports the Secretary-General’s initiative, and in the negotiations in autumn 2012 on the framework resolution on UN development activities under the Quadrennial Comprehensive Policy Review, we supported the idea of Delivering as One UN as the main approach to the UN’s operational activities at country level. However, the great variation in the developing countries’ sizes, income levels and issues to be addressed mean that the approach must be flexible and adapted to each country’s specific needs. Through its work in governing bodies and its dialogue with the organisations, the Government will increase the pressure on the organisations to take the necessary steps to promote UN reform at country level.

The Government will

promote Delivering as One UN as the main approach to the UN’s operational activities at country level,

seek to ensure that UN funds, programmes and specialised agencies actively implement the reforms and send clear messages to their country offices to carry them out and practise financial management,

seek to increase the authority of UN resident coordinators,

seek to strengthen cooperation between the UN system and the World Bank.

4.4 The UN’s humanitarian efforts

Humanitarian crises are becoming more complex and far-reaching. Climate-related natural disasters affect millions of people every year. Crises increase the risk of malnutrition and the spread of infectious diseases such as malaria, diarrhoea and pneumonia, and lead to the collapse of health care and education services. Internal conflicts and lack of resources force people to flee their homes. Small arms and light weapons, cluster munitions and landmines in the wrong hands have enormous economic, social and humanitarian consequences. The practice of sexualised violence in armed conflict has also increased. By the end of 2011, over 35 million people had been displaced due to conflict, violence or crises, and 26.4 million were internally displaced. Children and young people in developing countries are particularly vulnerable.

Figure 4.4 Internally displaced people in a camp in El Faser, Darfur, wheeling water containers.

Source Photo: UN Photo/Albert Gonzalez Farran.

The main components of Norway’s humanitarian policy are described in the white papers Norwegian Policy on the Prevention of Humanitarian Crises (Report No. 9 (2007–2008) to the Storting), and Norway’s Humanitarian Policy (Report No. 40 (2008–2009) to the Storting). The focus of the present white paper is on the UN’s central role in the humanitarian system and on how the Organisation’s humanitarian efforts can support Norwegian humanitarian policy.

4.4.1 Global humanitarian challenges

The world expects that the UN will provide protection and assistance in humanitarian crises. However, humanitarian situations are becoming increasingly complex. The principles of impartiality, humanity and neutrality are continually being tested by armed conflict and political instability. The Government believes that these principles are necessary for effective humanitarian assistance, and that there must be a clearly defined division of roles between humanitarian organisations, other civilian efforts, and military forces. This means that such assistance must be based on humanitarian needs and clearly separated from other types of assistance. Strengthening and safeguarding humanitarian law is therefore a high priority for Norway. Given the complexity of international humanitarian situations, this will require greater resources in the years to come.

Strengthening humanitarian law also increases the security of UN personnel, and the Organisation itself is taking steps to protect them. Based on the strategy To Stay and Deliver, the UN Emergency Relief Coordinator has taken the initiative to change the UN’s approach from avoiding risk to limiting risk and making it possible for the UN organisations to maintain a presence in difficult situations.

In an armed conflict it is important that UN humanitarian organisations and other humanitarian actors, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), maintain a dialogue with all armed groups, regardless of their background and political affiliation, in order to ensure compliance with humanitarian law and that the civilian population is actually being protected and helped. In some conflicts, attempts have been made to restrict contact with armed groups on the grounds that it might encourage terrorism; for example objections were made to the contact between UN humanitarian organisations and Al-Shebab in Southern Somalia. In 2011, restrictions on such contacts stood in the way of a UN presence and provision of effective humanitarian assistance in a number of cases. Norway therefore considers it important to ensure that measures against terrorism, even when adopted by the Security Council, do not undermine the ability of humanitarian organisations to work in accordance with humanitarian law and humanitarian principles.

4.4.2 The UN’s roles: leadership, coordination and financing

The UN is the core of the international humanitarian system, together with the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and a number of NGOs. The Government wishes to emphasise that the UN should have an overarching, strategic role in coordination and policy-making, based on UN norms. The Organisation also has an important role as a mouthpiece in connection with humanitarian crises, and in mobilising the necessary funding. It has now taken important steps to strengthen its humanitarian role.

The establishment of humanitarian funding mechanisms has strengthened the UN’s ability to lead and coordinate humanitarian efforts at country level. The establishment of the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) marked a new direction in humanitarian financing, and has improved the UN’s capacity for rapid response in humanitarian crises. Norway has been one of the largest donors to CERF since its establishment in 2006. In 2011 we contributed NOK 385 million, which amounted to 14.7 % of the total contributions to the fund that year. Norway has made a point of being a stable donor, and pays its contributions early in order to provide the predictability necessary for a more effective crisis response. We will continue to strengthen the humanitarian funding mechanisms, including CERF and the common humanitarian funds. We will also seek to strengthen the capacity of humanitarian pooled funding mechanisms at country level to finance transition situations, including strengthening of local and national capacity to provide effective humanitarian assistance.

Textbox 4.5 A high level of preparedness and strong partnerships – NORCAP

“In the right place at the right time” is the motto of NORCAP – the standby roster operated by the Norwegian Refugee Council and fully funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

NORCAP’s aim is to strengthen the capacity of the humanitarian system, not least of the UN, to provide rapid and effective humanitarian assistance and protection by seconding key personnel. NORCAP was established in 2009, as a merger of various standby rosters operated by the Norwegian Refugee Council.

From 2009 to the end of 2011, the Refugee Council had concluded 1 134 agreements, most of them with UN organisations, such as UNICEF, UNHCR, FAO and the World Food Programme (WFP). At any one time, an average of 150 persons are on assignment to countries in crisis such as South Sudan, Pakistan, the Palestinian Territory and Haiti. NORCAP’s roster numbers 850 men and women who can be deployed at 72 hours’ notice. Forty per cent are Norwegians, while 60 % are from the South. Forty per cent are women.

Three fields of expertise are in most demand: logistics, coordination and protection, including protection of children. Other fields of expertise that are often called for are crisis management training, information/communication, water and sanitation, food security and livelihoods.

NORCAP also strengthens South–South emergency preparedness and facilitates UN efforts to form and support partnerships.

Although good progress has been made on reform, the earthquake in Haiti and the floods in Pakistan revealed weaknesses in the UN system’s capacity to respond to large-scale natural disasters. The UN Emergency Relief Coordinator is continuing the efforts to strengthen and consolidate existing reforms. These include strengthening OCHA’s leadership and presence in the field, especially in complex crises, and a clearer division of work, more strategic appeals, and better management information systems and needs assessments. Together with like-minded countries, Norway will promote the agenda for greater efficiency in UN governing bodies.

4.4.3 Partnership

Cooperation and coordination of humanitarian assistance is vital when crises and disasters occur. Partnerships between the UN and NGOs have strengthened the response capacity of the humanitarian system, but these partnerships still need to be further improved. However, the UN has made good progress on concluding agreements with individual countries to make civilian capacity and materiel available to the UN at short notice in the event of a crisis.

The UN has developed good relations and established a good division of work with NGOs in many countries, but the relations are often those of contractor and service provider, and are perceived as asymmetric. Reaching people with humanitarian needs requires NGOs that are already on the ground and have partners and experience that can be further developed. Thus in many cases these organisations are in a better position than a UN organisation to provide local humanitarian support. NGOs are particularly relevant in cases where the UN lacks access to an area for security reasons. Norway will therefore seek to ensure that NGOs enter into more strategic cooperation relations with the UN that will lead to a more effective division of work and partnerships on more equal terms. NGOs should be given greater responsibility for cluster coordination at country level, and Norway will follow this up.

New actors are continually entering the scene, both as donors and as operators. After the earthquake in Haiti it is estimated that around 10 000 NGOs were providing emergency assistance in the field. Although many of them were small, the sheer number demonstrates the difficulties of coordination. Among the new donors are Turkey and Qatar, which are providing valuable contributions. The fact that there is widespread engagement in the UN’s humanitarian efforts is promising, and Norway placed great emphasis on this during its chairmanship of the OCHA Donor Support Group.

Figure 4.5 Turkey has provided a valuable contribution in Somalia. Mogadishu, Somalia, 2011.

Source Photo: UN Photo/Stuart Price

The growth in the number of actors makes it necessary to broaden the support base for the international humanitarian system and strengthen ownership of humanitarian principles in both the North and the South. Norway will work for greater ownership, a broader humanitarian donor community and an enhanced dialogue with countries in the midst of a humanitarian crisis. We are working in close cooperation with the ICRC and the UN system to achieve these goals.

4.4.4 Disaster prevention and transition situations

The Government believes that long-term measures to prevent and mitigate the effects of natural disasters must be given priority. At the same time we should seek to ensure the use of short-term measures for effective post-disaster reconstruction and a smoother transition to long-term development. A long-term perspective needs to be adopted right from the beginning, for example with respect to infrastructure, food security and social services. Lack of funding for long-term efforts has proved to be a problem, since it is easier to mobilise resources to address immediate concerns when a crisis has just occurred.

Prevention and early recovery require coordination and an integrated approach, which the Government believes is a UN responsibility. Traditional prevention and climate change adaptation measures are both essential and should be better coordinated. A clear division of labour between the organisations involved is also needed, and health services are a basic requirement for boosting the resilience of local communities. These efforts should be coordinated across the various UN organisations, which will enhance the UN’s capacity to coordinate the work of all the actors in question. Norway will seek to ensure that mechanisms are in place to strengthen leadership in the fields of prevention and preparedness.

Figure 4.6 Damage in the wake of the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan.

Source Photo: UN Photo/Evan Schneider.

Norway plays a leading role in the efforts to alter the framework conditions for humanitarian work in order to ensure that more resources are invested in prevention, adaptation to climate change and a more efficient humanitarian emergency response. The management of the common humanitarian funds must also take prevention into account. Flexible funding mechanisms will increase the UN’s ability to take steps immediately after a disaster has occurred and prevent the effects of the crisis from escalating. We will promote a more proactive culture of prevention and encourage the UN to play a more distinct role in such efforts.

Norway will also maintain a focus on conflicts that have been forgotten by the public. Funding is particularly a problem in protracted crises, where capacity-building of local and national actors is essential for provision of effective protection and humanitarian assistance. For refugees there are three types of permanent solutions: voluntary repatriation, local integration and resettlement. Although repatriation is the best solution in principle, in many cases it is impossible, for example due to the risk of continued persecution. Resettlement is restricted to a limited number of refugees who cannot be protected in their home country or region. Norway is one of the countries that offers resettlement to the largest numbers of refugees, a total of 1 200 a year over the last few years. The Government is considering increasing the quota for resettlement refugees in extraordinary situations, as we did in spring 2011, when the stream of refugees from the Mediterranean region increased substantially due to the situation in North Africa. Norway wishes to maintain its quota for resettlement refugees at the current level while keeping open the possibility of increasing it in extraordinary situations. However, over 7 million refugees globally find themselves in a deadlocked situation, and for many of them the only alternative is local integration in the form of access to the labour market, and to health and education services. In order to find sustainable solutions for integrating internally displaced individuals into local communities, efforts must be made to facilitate closer cooperation between the national authorities, humanitarian actors such as UNHCR and OCHA, and development actors such as UNDP and the World Bank. The focus must be on protecting civilians, combating sexualised violence and protecting refugees and the internally displaced.

4.4.5 Humanitarian disarmament

Armed violence is an increasingly global problem and a threat to health, life and fundamental human rights. It occurs not only in ordinary conflict situations but also outside them, and causes an average of 2 000 deaths a day, mostly from small arms and light weapons.

Norway has given high priority to combating armed violence, among other things by focusing on humanitarian disarmament, which aims to prevent and reduce armed violence in the broadest sense. Humanitarian disarmament also includes the Mine Ban Convention and the Convention on Cluster Munitions. Since the Mine Ban Convention entered into force in 1999, the number of new victims has been reduced from over 20 000 a year to well under 5 000. The convention now has 160 states parties. The Convention on Cluster Munitions entered into force in 2010, and has been ratified by more than 70 countries. Norway holds the presidency of the convention for the period 2012–13.

Armed violence needs to be seen as a humanitarian and development problem, and Norway has played an active role in setting the issue on the international agenda. We are cooperating with for example UNDP on strengthening national capacity for prevention and reduction of armed violence in countries where it is a serious problem.

We are also seeking to ensure that international conventions and agreements on humanitarian disarmament are adopted, complied with, and incorporated into national law and practice. However, traditional UN negotiations on weapons with unacceptable consequences for civilians have had few meaningful and concrete results. The Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) requires consensus among all its 114 states parties for the adoption of new legal instruments, and has mainly focused on regulation rather than prohibition. This made it impossible to obtain a ban on landmines or cluster munitions within the existing mechanisms. Both the Mine Ban Convention and the Convention on Cluster Munitions were therefore negotiated outside the UN, in processes that were driven by a partnership of civil society, humanitarian organisations, relevant UN organisations and interested states. However, a number of UN field-based organisations had a central role in the negotiations on both conventions, and the UN provided high-level political support and practical assistance throughout the process.

The UN’s operational activities are also important for the implementation of international agreements. Organisations like UNDP and UNICEF have programmes for strengthening national capacity to undertake mine clearance and offer assistance to victims. However, some UN organisations have a tendency to be bureaucratic, ineffective and of little relevance in both policy discussions and practical implementation. Norway will seek to ensure that the most relevant organisations intensify their efforts in this area. Grants allocated through various channels, mainly NGOs, can be used strategically to support Norwegian priorities, enabling us to assist countries to comply with their obligations under the various conventions.

The Government will

seek to strengthen the UN’s leadership role in humanitarian crises,

mobilise more donors and supporters for humanitarian efforts in general and for UN humanitarian efforts in particular,

contribute to building partnerships, especially through the standby rosters under the Norwegian Refugee Council,

seek to strengthen the UN’s role as a voice for humanitarian principles, and safeguard the division of roles between humanitarian operations, other types of civilian efforts and military peacekeeping forces and political operations,

seek to strengthen the integration of crisis and disaster prevention efforts into UN activities and UN funds and programmes,

participate, in cooperation with NGOs and the UN, in developing practical solutions for funding the transition from humanitarian assistance to long-term development assistance,

seek to strengthen the capacity of UN organisations to help countries implement the Mine Ban Convention, the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and other such instruments, especially through capacity-building among national authorities in the countries concerned.