Part 3

How state ownership is exercised

8 The State shall be an active owner

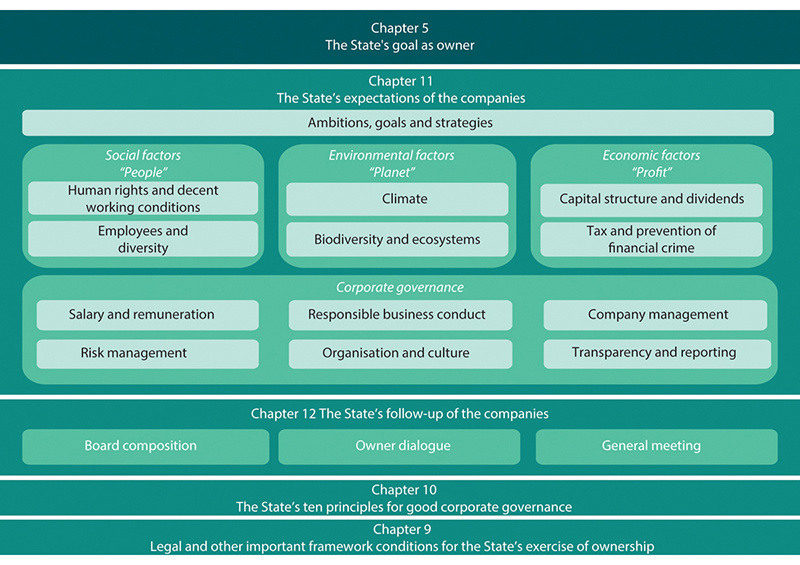

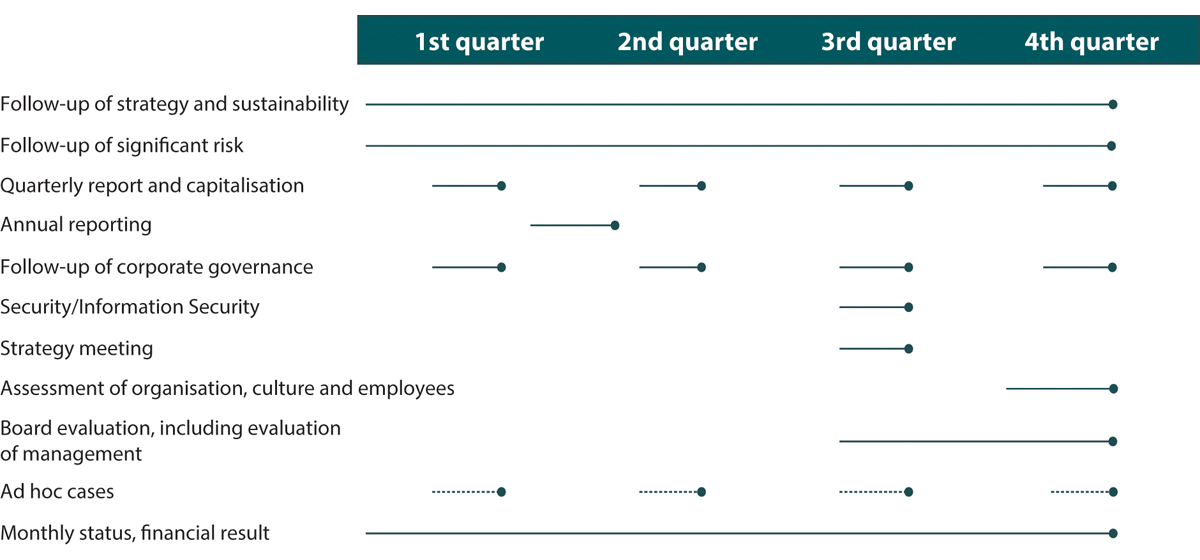

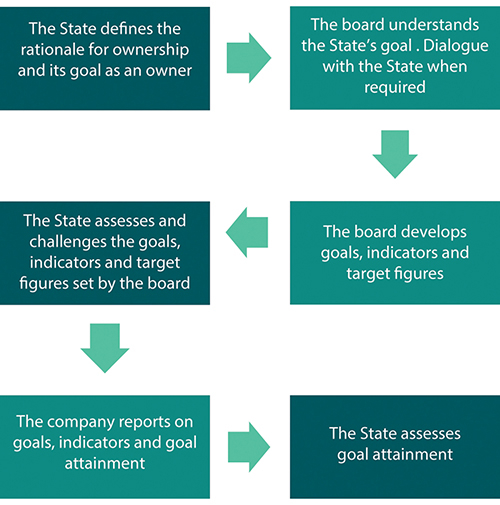

The Government has clarified through the State’s ten principles for good corporate governance that the State shall be an active and responsible owner with a long-term perspective, see Chapter 10. The State’s exercise of ownership shall contribute to the attainment of the State’s goal as an owner, whether this be the highest possible return over time in a sustainable manner or sustainable and the most efficient possible attainment of public policy goals, see Chapter 5. Among other things, this takes place by the State setting clear expectations of the companies, electing competent boards, systematically following up the companies, and voting at general meetings, see Figure 8.1.

Norway is considered to be far ahead internationally in terms of the exercise of state ownership.1 Among other things, this is due to the fact that a broad political consensus has developed over time regarding the key elements of the framework conditions and principles for the State’s exercise of ownership in line with generally recognised principles for corporate governance. This has contributed to predictability for the companies and the capital market, which has been a strength of Norwegian state ownership.

Figure 8.1 The State’s exercise of ownership.

The Government’s ambition is that the Norwegian State’s exercise of ownership shall be in accordance with the best international practice. The State shall be an active owner with a long-term perspective in line with good and responsible private owners. The Government will continue to further develop and professionalise the State’s exercise of ownership in order to contribute to public assets being managed and developed as best as possible. The State’s exercise of ownership should be carried out as competently and consistently as possible across the ministries. The good and uniform exercise of ownership strengthens trust in the State as owner and contributes to increased goal attainment.

8.1 How the State shall be an active owner

Active ownership shall be exercised in accordance with the division of responsibilities and roles laid down in company law between the State as owner of companies, on the one hand, and the board and general manager on the other.2 Together with the State’s ten principles for good corporate governance, the division of roles laid down in company law establishes the framework conditions for the State’s exercise of ownership. The State as owner will actively utilise the room to manoeuvre within these framework conditions in line with the practices of good and responsible private owners. State ownership shall not be an obstacle to exercising value-creating ownership. Among other things, the State shall, in the following manner, be an active owner within the division of roles and responsibilities upon which company law is based:

Use of the general meeting3

Voting on matters that, by law, must be presented to the owners: By voting at the general meeting, the State will actively use its ownership authority in matters that, by law, have to be presented to the general meeting, see Chapter 9.3. Among other things, this applies to the election of the board, specification of board remuneration, approval of the annual accounts and any annual report, distribution of dividends, election of the auditor, approval of the auditor’s fee, approval of the board’s guidelines for executive remuneration, advisory voting on the board’s remuneration report, amendments to articles of association, changes in share capital, etc. Active use of voting rights is particularly relevant in the event of poor goal attainment in the company over time or significant deviations from the State’s expectations; however, it may also be relevant when the State wishes to express its view regarding the board’s ambitions for the company. In these cases, the State as owner may also exercise its voting rights to change the composition of the board or change the company’s capital structure, see Chapter 12.6.

Voting on matters that the board chooses to present to the owners: The general meeting may hand down decisions on all matters that, pursuant to law or the articles of association, must not be made by other company bodies. The board will not normally present matters to the general meeting that the board is responsible for pursuant to company law. However, there may be good reasons for the board selecting to present matters of significant strategic importance to the company at the general meeting. The State will exercise its voting rights in such matters unless these matters are of such a nature that they violate the division of responsibilities and roles between the owners and the board upon which company law is based.

The right to have matters considered at the general meeting: The State will exercise its right as owner to have matters considered at general meetings when this is relevant and in accordance with principles pertaining to company law. Among other things, the State may request that the general meeting considers the election of the board (even if the board is not up for election), that the board’s guidelines for executive remuneration be presented to the general meeting once more (even if they have not been amended), amendments to the company’s articles of association and other matters of importance to the owner. However, the State exercises caution when instructing companies on individual matters.4 This is because it undermines the division of roles and responsibilities set out in company law, see Chapter 9.3.

The right to convene an extraordinary general meeting: The State will exercise its right as owner to request that the board convenes an extraordinary general meeting when this is relevant and in accordance with principles pertaining to company law.

Explanation of vote: In order to clarify the State’s perspective or the assessments behind the State’s voting, the State will, if necessary, use an explanation of vote not only when the State votes against a decision, but also when the State votes in favour of the board’s proposal. The State will normally request that the explanation of vote is recorded in the minutes. Among other things, the purpose of this is to be transparent about the State’s exercise of ownership.

Election of board members

The board is responsible for the management of the company. The State generally has a significant ownership interest and by being involved in electing the boards has the opportunity to influence the company’s management by contributing to ensuring that the company has a competent and well-functioning board. The State’s ownership policy dictates that all boards and board members are subject to an annual assessment, irrespective of whether they are up for re-election. Among other things, the purpose of the assessments is to determine the board and the board members’ contribution to the company’s goal attainment and work with the State’s expectations, and whether the board has the correct expertise, see Chapter 12.5. In the event of poor goal attainment over time or significant deviations from the State’s expectations, the State may vote at the general meeting to replace all or parts of the board.

Regulation in the articles of association

Through the company’s articles of association, the owners set the framework for the board’s management and the general manager’s day-to-day operation of the company. Company law stipulates that certain matters need to be regulated in the articles of association. However, the legislation does not prevent other matters from being regulated in the articles of association unless otherwise stipulated in the individual statute. For example, for most unlisted companies, the State has stipulated in the articles of association that the board must submit guidelines and an annual report on the remuneration of senior executives to the general meeting in accordance with Sections 6-16 a and 6-16 b of the Public Limited Liability Companies Act and associated regulations. Amendments to the articles of association must be approved by the general meeting.5 If necessary, the State will also exercise its right to propose amendments to the articles of association to the general meeting in order to establish the company’s activities in line with, among other things, the State’s rationale for ownership and goal as owner.

Set clear expectations

The board is responsible for managing the company; however, the State as owner sets and follows up specific expectations of the boards. By setting expectations of the boards, the State contributes to achieving the State’s goal as owner. As the expectations are specific, the concerns of the State as an owner are made clear to the boards. However, it is up to the boards to consider how the companies can best work with the various expectations tailored to their activities. When the State assesses the work and composition of the board, the company’s work with the various areas of expectations and the board’s contribution to this are assessed.

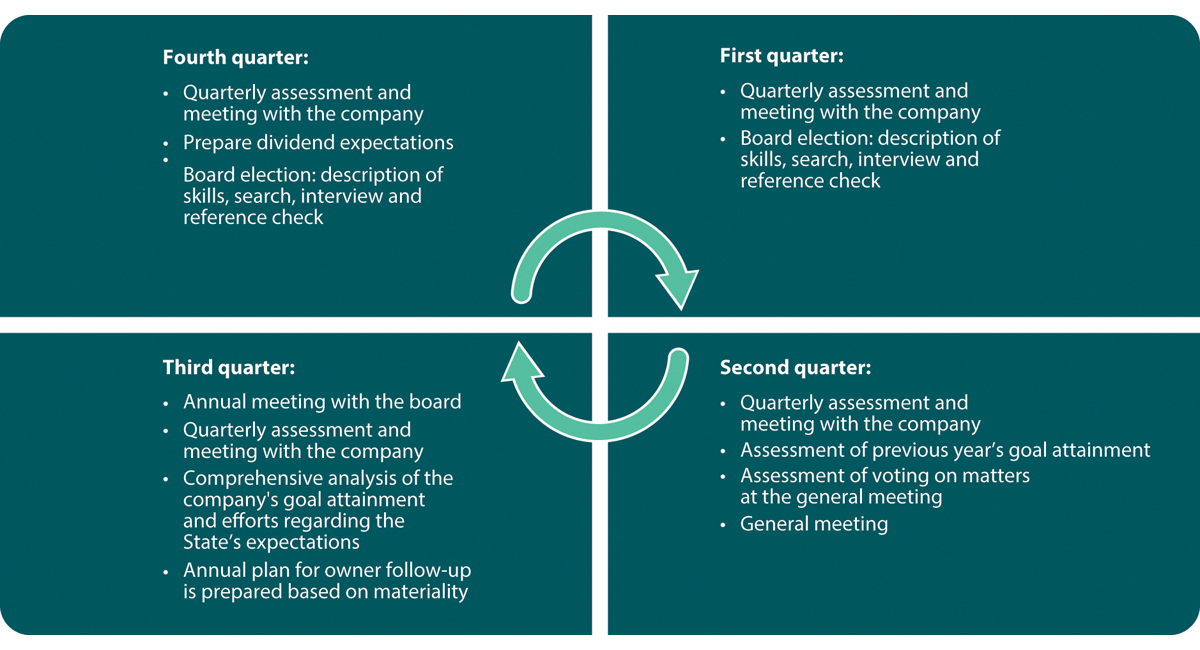

Use of owner dialogue

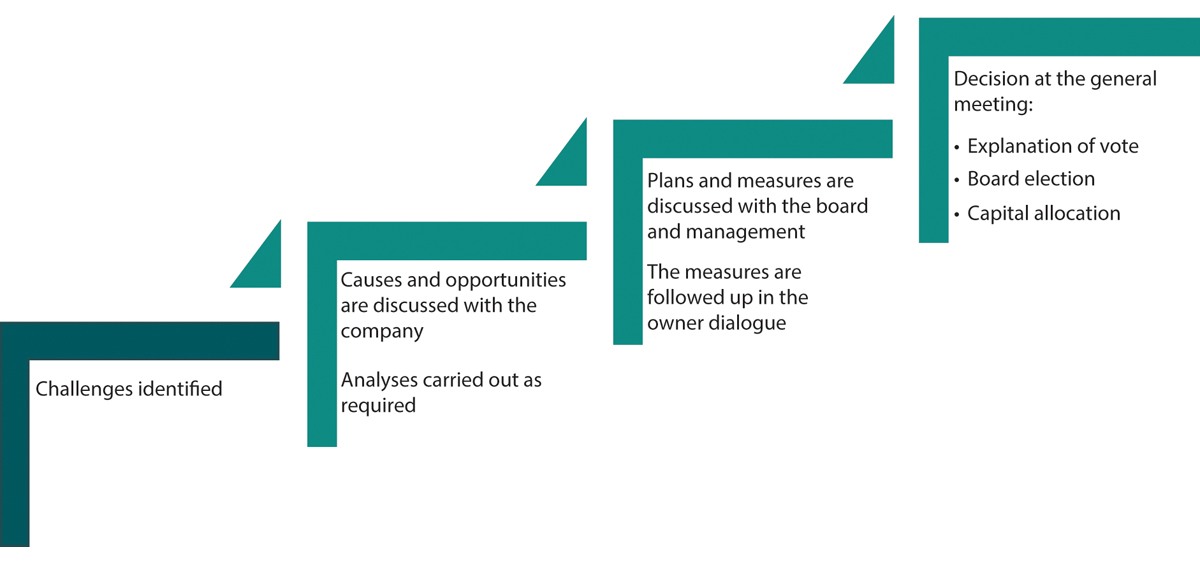

The State actively uses owner dialogue to follow up the companies’ results and goal attainment, including the companies’ work on the State’s expectations, and other relevant topics and issues. Quarterly meetings are the core part of the owner dialogue; however, the State typically also holds other meetings on specific topics with the executive management and the board, see Chapter 12.1. Through the owner dialogue, the State will raise matters, ask questions and communicate points of view that company management can consider in relation to its activities and development. This serves as input to the company management, not as instructions or orders. The board shall manage the company in accordance with the interests of the company and all shareholders, and must make their own specific assessments and decisions. Matters that require the owners’ support must be considered at the general meeting.

In addition to quarterly meetings, meetings on special topics and ad-hoc meetings, the State will have an annual meeting with the entire board if this is considered appropriate. Among the reasons for the State having these meetings as owner is to develop a good dialogue with the board, raise relevant expectations and discuss the company’s goal attainment.

As part of the annual board assessment for companies that are wholly-owned by the State, the State will meet with all owner-elected board members and the general manager. The State will also endeavour to conduct interviews with board members elected by and among the employees, cf. Chapter 12.5. In the companies with a nomination committee, the committee is the body that conducts this dialogue.

The State will normally also conduct onboarding meetings with newly-elected board members in the companies that are wholly-owned by the State. Onboarding meetings also help the board members to gain a better understanding of the State’s rationale for ownership and the State’s goal as an owner of the company in question, as well as the State’s expectations of the companies.

Offer knowledge sharing through professional seminars

The State has a large portfolio of companies. The State will hold professional seminars for the companies to contribute to knowledge sharing on various relevant topics that are of importance to the companies’ goal attainment.

Support for, and possible participation in, transactions that contribute to goal attainment

The State will assess any potential initiatives presented by the company that are expected to contribute to the State’s goal as an owner. The State will act in accordance with market practices when conducting a dialogue about, and in the event of, potential participation in share capital increases or other transactions that are expected to increase a company’s value, see Chapter 12.7.

8.2 The State shall demonstrate transparency about its ownership and exercise of ownership

In its capacity as owner, the State manages substantial assets on behalf of society as a whole. Transparency is decisive in order to give the general public, co-owners and potential new shareholders, competitors, lenders and others insight into how the State exercises its ownership, among other things, to be able to evaluate the State as an owner and determine whether there is fair competition between companies with and without a state ownership interest. Transparency creates predictability and is important if the general public is to trust that these assets are being managed in an optimal manner. Democratic considerations are thereby safeguarded. As a result of the Norwegian state’s extensive ownership, transparency is also important if investors are to trust the Norwegian capital market.6

Since 2002, a report to the Storting on the State’s overall direct ownership in companies (white paper on ownership policy) has been presented in each parliamentary session.

In addition, each year the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries presents the State Ownership Report, which provides an overview and description of the State’s direct ownership in companies in the preceding year, see Box 8.1.

Textbox 8.1 State Ownership Report

The State Ownership Report is the annual report for the State’s direct ownership in companies and shall contribute to providing a high degree of transparency. The report provides an overview of the ownership scope and key figures, the State’s rationale and goals for its ownership in each of the companies, and information about the State’s exercise of ownership. In addition, the report contains information about each company, including the companies’ goals and goal attainment, important events during the year in question, financial developments and significant key figures, including the companies’ greenhouse gas emissions. The report also contains information about the companies’ reporting on the State’s expectations, as well as overviews of board members, remuneration of the board and general manager and the gender balance of the board and management group. The report is published in June each year on the Government’s state ownership website (www.eierskap.no).

9 Legal and other important framework conditions for the State’s exercise of ownership

The legal framework conditions for the State’s exercise of ownership are primarily established through the constitutional framework in the Constitution of Norway, and provisions in company law pertaining to the division of roles between an owner and the company’s management, which consists of the board and general management. This chapter provides an overview of the most important framework conditions for the State’s exercise of ownership pursuant to the Constitution of Norway and company law.7 The provisions in the EEA Agreement relating to state aid are also discussed. Other laws, for example, the Public Administration Act, Freedom of Information Act, Securities Trading Act and Competition Act, also impose legal requirements on the State’s exercise of ownership.8 These are not discussed here.

In addition to legislation, there are several other rules and regulations that are of importance to the State’s exercise of ownership. This chapter discusses rules pertaining to the right of civil servants, members of parliament and members of the government to hold directorships, as well as regulations for financial management in the State.

This chapter also discusses the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises9 and the Norwegian Code of Practice for Corporate Governance.

9.1 Constitutional framework – the government administers the State’s ownership10

Pursuant to Article 19 of the Constitution, the Government administers the State’s shares in private and public limited liability companies and ownership in companies organised in other corporate forms, such as state enterprises and special legislation companies. Pursuant to Article 12, second paragraph of the Constitution, the administration of state ownership is delegated to various ministries. The Minister’s administration of ownership is exercised under constitutional and parliamentary responsibility.

Pursuant to Article 19 of the Constitution, the minister must administer the State’s ownership in companies in accordance with parliamentary resolutions concerning the individual company, general statutory provisions and other parliamentary resolutions. The provision expressly authorises the Storting to instruct the Government in matters pertaining to state ownership.

The Storting has no direct relationship with the companies with a state ownership interest. Parliamentary resolutions concerning companies with a state ownership interest must be resolved by the company’s general meeting in order to legally bind the company, unless the resolutions are set out in law.

Article 19 of the Constitution does not grant the minister authority to change the State’s ownership interest in a company, for example through the purchase or sale of shares, resolutions regarding or participation in capital increases or support for other transactions that change the State’s ownership interest. Such actions must be based on a parliamentary resolution whereby the minister is granted authorisation.

Several of the listed companies have so-called buyback programmes in which the company is authorised to purchase its own shares in the market with a plan to cancel the shares. A contractual framework has been established for such cases to ensure that the State’s ownership interest in the company remains unchanged during the buy-back programme. In line with previous white papers on ownership policy and practice, the minister may in such cases, without obtaining the consent of the Storting, endorse the State’s contribution to such share buy-back programmes and enter into agreements in line with the established contractual framework on the condition that the State’s ownership interest in the company remains unchanged.

The Storting’s appropriation authority pursuant to Article 75 (d) of the Constitution also entails that the Storting’s consent is required for changes in the State’s ownership interest in a company and for decisions on capital infusions that lead to government expenditure.

Companies in which the State has ownership interests will usually be able to purchase and divest shares in other companies and acquire or dispose of parts of business activities when this is a natural part of the adaptation of the company’s object-specific activities, without the approval of the Storting being required. For companies where the State is the sole shareholder, the consent of the Storting must be obtained regarding decisions which would significantly alter the State’s commitment or the nature of the company’s activities.11 When the State is a joint shareholder, the question of whether the matter should be discussed by the Storting in advance will arise for matters of such scope that they must be brought before the general meeting (for example, demergers or mergers). Depending on the size of the State’s ownership interest in the company, it may be necessary to present the matter to the Storting; however, the clear general rule is that matters concerning the purchase and sale of shares in other companies, including the purchase and sale of subsidiaries, are the responsibility of the company’s management, cf. footnote 5.

It is established practice for the Government to present to the Storting the rationale for state ownership and the State’s goal as an owner of each company with a direct state ownership interest.

The Office of the Auditor General of Norway conducts audits of the minister’s (the ministry’s) administration of the State’s ownership, and reports to the Storting accordingly. The Office of the Auditor General’s monitoring of the administration of the State’s ownership is described in more detail in Chapter 3 (Corporate control) of the Instructions for the Activities of the Office of the Auditor General.12

9.2 Corporate forms used for state ownership

The companies with state ownership are organised into different legal corporate forms, see Figure 4.2. Among the common features of these corporate forms are that they are based on a clear division of roles between the owner and the company management, consisting of the board and the general manager, and that the management of the company is the board’s responsibility.13 Another common feature of the corporate forms used for state ownership is that the State’s liability as owner is limited to the equity invested in the companies, and that the companies therefore may go bankrupt.14

The companies that primarily operate in competition with others are also subject to the same legislation as privately owned companies.15 Relevant legislation will, for example, include the Accounting Act, Auditors Act, Competition Act, Securities Trading Act, tax laws and, if applicable, sector-specific legislation. The companies that do not primarily operate in competition with others are normally also subject to such legislation. Some of the companies also fall under the scope of the Freedom of Information Act and/or the rules for public procurements.16

The following corporate forms are used for the State’s ownership:

Partly owned private and public limited liability companies

With the exception of Innovasjon Norge, all of the companies in which the State is a part-owner are organised as private or public limited liability companies. These companies are subject to the general provisions of the Limited Liability Companies Act and the Public Limited Liability Companies Act.

State-owned limited liability companies17

A state-owned limited liability company is a limited liability company in which the State owns all the shares, cf. Chapter 20, II of the Limited Liability Companies Act. The majority of the companies that are wholly-owned by the State are organised as state-owned limited liability companies, regardless of the State’s rationale for ownership and the State’s goal as owner. These companies are subject to the general provisions of the Limited Liability Companies Act18 with certain special provisions that are set out in Sections 20-4 to 20-7, see Chapters 9.3.2 and 9.3.3.

State enterprise

State enterprises are organised in accordance with the Act relating to state enterprises.19 State enterprises cannot have owners other than the State. The State currently has several enterprises organised in accordance with this act. State enterprises are largely regulated in the same manner as state-owned limited liability companies, however with some exceptions, see Chapters 9.3.2 and 9.3.3.

Special legislation companies

The term special legislation companies covers a small, diverse group of companies. A common characteristic of these companies is that they are regulated by special legislation adopted for the individual company.20 With the exception of Innovasjon Norge, it has been laid down in law that the State shall be the sole owner of the special legislation companies. The regional health authorities are a specific form of special legislation company. The specialist health service is organised as regional health authorities and health trusts. The former can only be established and owned by the State, while the latter, which provide health services and support functions, can only be established and owned by the regional health authorities. Rules that deviate from the provisions of the Limited Liability Companies Act may apply to the special legislation companies, including the authority assigned to the company’s board. It is a typical feature of several of the special legislation companies that specific matters must be presented to the owner.

Choice of corporate form

Having multiple corporate forms for companies that are wholly-owned by the State result in different and non-uniform framework conditions for the State’s exercise of ownership. The OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises recommend that governments simplify and standardise the legal corporate forms used for companies with a state ownership interest.21 Private limited liability companies are a well-known corporate form, including outside Norway. This corporate form is the most commonly used for companies with a state ownership interest, irrespective of the State’s rationale for ownership and the State’s goal as owner. The company law framework that is set out in the Limited Liability Companies Act ensures predictability in the State’s exercise of ownership, for the companies, the State and other stakeholders alike. Other corporate forms are used where these are well suited and there is a special rationale for doing so, cf. Chapter 9.3.2 and 9.3.3.

9.3 Company law framework

9.3.1 The minister’s authority in the company

The legal basis for the minister’s authority as owner in a limited liability company is Section 5-1 of the Limited Liability Companies Act, which reads as follows: «The shareholders exercise supreme authority in the company through the general meeting.» A corresponding provision applies to public limited liability companies, state enterprises and most special legislation companies.22 For state enterprises and some special legislation companies, the term «corporate assembly» is used instead of «general meeting»; however, the reality is the same. In this white paper, the term general meeting is used as a collective term for both.

The general meeting may hand down decisions on matters that, pursuant to law or the articles of association, must not be handed down by other company bodies.

Pursuant to the Limited Liability Companies Act and corresponding provisions in other company legislation, the general meeting shall, among other things, elect board members,23 determine the remuneration of the board members, approve the annual accounts and, if applicable, the annual report, determine the distribution of dividends,24 elect the auditor, approve the auditor’s fee, and resolve changes to the share capital and amendments to the articles of association.

The provision in Section 5-1 of the Limited Liability Companies Act entails that the general meeting has authority over the board and may issue instructions to the board. These may be general instructions or special instructions relating to individual matters. However, the general meeting’s authority to issue instructions is not unlimited. The board must not comply with instructions that are in violation of law or the articles of association. The board’s primary obligation is with the company as an independent legal entity. In principle, the board is obligated to comply with instructions issued by the general meeting within the framework set out in the Limited Liability Companies Act.

For companies with multiple shareholders, legislation pertaining to limited liability companies sets requirements for the protection of minority shareholders. The board cannot be instructed to make decisions that are contrary to the principle of equality or the collective interests of the shareholders.25

The State exercises caution when instructing companies on individual matters.26 This is because it undermines the division of roles and responsibilities set out in company law. The State’s liability as owner is limited to the capital invested. Pursuant to Section 6-12 of the Limited Liability Companies Act/Public Limited Liability Companies Act, the board is responsible for the day-to-day management of the company. If the board is issued instructions through the general meeting, the responsibilities can be pulverized, and the State may be held liable. The fact that the State is cautious about issuing instructions on individual matters must also be viewed in connection with the corporate form having been selected to grant company management the freedom to act. Corporate legislation is based on an assumption of mutual trust between the shareholders and a company’s board. If shareholders issue instructions to the board, this may be perceived as the board not having the shareholders’ trust, and could thus result in the board members resigning from their positions. Active use of instructions at the general meeting may also affect the parliamentary and constitutional liability that can be asserted vis-à-vis the minister if the minister, through a resolution of the general meeting, makes decisions that are customarily the preserve of the company’s board.

Another aspect of Section 5-1 of the Limited Liability Companies Act is that the minister has no authority within the company in the absence of the general meeting structure27.

9.3.2 The company’s management manages the company

Limited liability companies and the other corporate forms used for companies with a state ownership interest are based on a clear division of roles between the company’s owners, on the one hand, and the company’s management, consisting of the board and the general manager, on the other.

Pursuant to Sections 6-12 the Limited Liability Companies Act and corresponding provisions in other company legislation, management of the company falls within the authority of the board. It is the board’s duty to ensure that the company’s activities are properly organised. The board shall stipulate plans and budgets for the company’s activities to the extent that this is necessary. The board shall also remain informed about the company’s financial position and ensure that its activities, accounts and asset management are subject to adequate control.

The board appoints the general manager.28 The board shall supervise the day-to-day management and the company’s activities in general. The general manager is responsible for the day-to-day management of the company’s activities, cf. Sections 6-14 of the Limited Liability Companies Act/Public Limited Liability Companies Act. This means that the general manager must follow up the decisions made by the board. The board and the general manager shall manage and lead the company based on the interests of the company and the owners and in line with the company’s articles of association and other decisions made by the general meeting. The board and the general manager are responsible for ensuring that the company is operated in accordance with applicable laws and rules. In their management of the company, the board members and the general manager are subject to personal liability in damages and criminal liability as stipulated in company law.

Limitations in the management’s management of companies wholly-owned by the State

For wholly state-owned companies, the law stipulates certain special provisions that limit the general rules described above, and which grant the State as owner extended control.29

In state-owned limited liability companies and state enterprises, the general meeting is not bound by the dividend proposal made by the board or corporate assembly and may adopt a higher dividend than that proposed by the board or corporate assembly, cf. Section 20-4(4) of the Limited Liability Companies Act and Section 17 of the Act relating to state enterprises.

For state enterprises, it has also been enshrined in law that matters assumed to have a significant bearing on the object of the enterprise or which will significantly alter the enterprise’s nature shall be submitted to the owner in writing before the board makes its decision, cf. Section 23, second paragraph of the Act relating to state enterprises. The Act also stipulates that the minutes of board meetings shall be sent to the ministry that manages the State’s ownership of the state enterprise, cf. Section 24, third paragraph of the Act relating to state enterprises. Sending minutes of board meetings to the ministry is normally not considered sufficient to keep the owner informed about a specific matter.

Specific restrictions on the board’s authority have been enshrined in law for the regional health authorities, cf. Sections 30–34 of the Act relating to health authorities and health trusts.30 Legislation that places restrictions on the board’s authority also applies to the other special legislation companies and certain other companies.31

9.3.3 Special rules for companies wholly-owned by the State

The Limited Liability Companies Act contains some special provisions for state-owned limited liability companies, cf. Chapter 20, II of the Limited Liability Companies Act. In addition to what is described in Chapter 9.3.2 concerning restrictions in the management’s management of companies wholly-owned by the State, one of the differences between state-owned limited liability companies and limited liability companies not wholly-owned by the State is that the general meeting elects the shareholder-elected members to the board even if the company has a corporate assembly, cf. Section 20-4(1) of the Limited Liability Companies Act. 32

A requirement for both genders to be represented on the boards also applies to state-owned limited liability companies and their wholly-owned subsidiaries, cf. Section 20-6 of the Limited Liability Companies Act. The same requirement applies to state enterprises, special legislation companies and public limited liability companies.33

Special rules also apply to the convening and holding of general meetings, cf. Section 20-5 of the Limited Liability Companies Act. Among other things, this provision states that if the general manager or a member of the board or corporate assembly disagrees with the resolution adopted, the person in question shall demand that his/her dissenting opinion be recorded in the minutes of the meeting. A similar provision also applies for state enterprises.34

In addition, the Office of the Auditor General has an extended right to supervise the minster’s administration of the State’s ownership of wholly state-owned companies, including the right to be notified of and attend the general meeting, cf. Section 20-7 of the Limited Liability Companies Act and Section 45 of the Act relating to state enterprises.

9.3.4 The minister’s authority as owner is influenced by the ownership interest35

The basic company law principles and the relationship between the minister and the company’s management are generally independent of the State’s ownership interest. However, when the State owns a limited liability company together with others, the provisions of the Limited Liability Companies Act that safeguard the interests of individual shareholders will have a bearing on the minister’s relationship with and influence over the company. This entails that, in these instances, the exercise of the State’s ownership can differ to some extent from cases where the State is the sole owner.

When the State is a part-owner in a company, the minister’s authority is limited by, among other things, the principle of equality set out in company law, cf. Section 4-1 of the Limited Liability Companies Act/Public Limited Liability Companies Act, and the rule prohibiting abuse of the general meeting’s authority, cf. Section 5-21 of the Limited Liability Companies Act/Public Limited Liability Companies Act, which are also applicable to other shareholders.36 The provision relating to abuse prohibits the general meeting from adopting resolutions that are liable to grant certain shareholders or others an unreasonable advantage at the expense of other shareholders or the company. This entails that the State, even as a majority shareholder, is prohibited by law from favouring itself at the expense of the other shareholders in the company. This is particularly relevant if the State as an owner wishes to assign the company tasks that are not in the company’s interests. In addition to the protection provided from the principle of equality and abuse provision, there are also a number of other provisions in company law that safeguard individual shareholders.

The following is a general overview of how a part-owner can influence a company pursuant to company law based on the applicable ownership interests:

9/10

An ownership interest of nine-tenths or more of the share capital and a corresponding share of the votes in a limited liability company entitle the majority shareholder to a compulsory buy-out of the other shareholders in the company.37

2/3 – qualified majority

An ownership interest of two-thirds or more of the share capital and a corresponding share of the votes in a limited liability company gives the shareholder in question control over decisions that require a two-thirds majority under company law. This includes decisions to amend the company’s articles of associations, decisions on mergers or demergers, increases and reductions in share capital, raising convertible loans, and conversion or dissolution of the company.

1/2 – simple majority

An ownership interest of more than half the share capital and a corresponding share of the votes in a limited liability company give the shareholder in question control over decisions that require a simple majority of the votes cast at the general meeting. This includes the approval of the annual accounts, including the distribution of dividends, the election of members to the board38 or corporate assembly, board remuneration, election of the auditor and approval of the auditor’s remuneration.

1/3 – negative majority

An ownership interest of more than one-third of the share capital and a corresponding share of the votes in a limited liability company give the shareholder in question negative control over decisions that require a two-thirds majority. This enables the owner to oppose amendments to the articles of association, changes in the company’s capital and other decisions of material importance, cf. the paragraph concerning a two-thirds majority.

9.4 The EEA Agreement – prohibition on state aid

The provisions in the EEA Agreement are neutral with regard to public and private ownership.39 The prohibition on state aid stipulated in Article 61(1) also applies to companies with a state ownership interest. This limits the State’s opportunities to place emphasis on non-commercial interests when exercising ownership in companies that engage in economic activity pursuant to Article 61 (1) of the EEA Agreement. The purpose of the rules is to create equal competitive conditions.

Six conditions must be met in order for a measure to be defined as state aid, cf. Article 61 (1) of the EEA Agreement: the aid recipient must be an undertaking and the aid must be granted by the public authorities, favour certain undertakings or the production of certain goods or services, confer an economic advantage on the recipient, distort competition and have the potential to affect trade between the EEA states.

In order to determine whether investments entail an advantage for the company and can thereby constitute state aid pursuant to Article 61 (1) of the EEA Agreement, the European Court of Justice and the European Commission have developed the so-called Market Economy Investor Principle40. If the State contributes capital on the basis of different considerations and terms to what a comparable private investor would be assumed to have required, this may indicate that the capital contribution involves an economic advantage for the company in question that may constitute state aid pursuant to Article 61 (1) of the EEA Agreement, provided that the other conditions are met. This means that the State must operate in accordance with the Market Economy Investor Principle when investing in a company, provided that all of the criteria in Article 61 (1) of the EEA Agreement are met, in order to avoid an investment becoming state aid.

The EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA) supervises compliance with the state aid regulations in Norway. The question of whether state aid has been provided can also be examined by Norwegian courts.

9.5 Other important framework conditions for the State’s exercise of ownership

9.5.1 Restrictions on the right to hold directorships

Civil servants and senior officials employed in a ministry or in other central government administrative bodies that regularly consider matters of material importance to the company or relevant industry are not eligible for election to the boards of such companies. This is stipulated in the Personnel Handbook for State Employees (Statens Personalhåndbok).41 The purpose of the prohibition is to prevent impartiality issues and constellations that weaken trust in the public administration’s decisions.

Furthermore, the Storting has decided that members of the Storting should not be elected to offices in companies subject to the Storting’s control, unless it can be assumed that the member in question will not stand for re-election.42 As a general rule, political leadership also cannot retain or accept paid or unpaid directorships.43

The Disqualification Act44 also contains provisions that provide for the possibility of imposing a period of disqualification on politicians, civil servants and other state employees when they move to a position outside the government administration.

9.5.2 Regulations on Financial Management in Central Government

«The Regulations on Financial Management in Central Government»45 contain guidelines on the State’s exercise of ownership. Among other things, the purpose of the regulations is to ensure that the State’s assets are managed in an efficient and proper manner. Section 10 of the Regulations states that:

«Agencies with overall responsibility for (…) independent legal entities wholly or partially owned by the central government, shall draw up written guidelines on how management and control powers shall be executed for each individual company or for groups of companies. (…)

The central government shall, within the framework of applicable laws and rules, manage its ownerships in accordance with general principles of corporate governance with special emphasis on:

a) that the chosen form of incorporation, the company’s articles of association, financing and the composition of its board are expedient in relation to the company’s object and ownership,

b) that the exercise of ownership ensures equal treatment of all owners and underpins a clear division of authority and responsibility between the owning entity and the board of directors,

c) that goals set for the company are achieved,

d) that the board of directors functions in a satisfactory manner.

Governance, monitoring and control including appropriate guidelines shall be adjusted to the size of the central government shareholding, the distinctive characteristics of the company, risk profile and significance.»

Section 16 goes on to state that:

«All agencies shall ensure that evaluations are performed to obtain information on efficiency, achievement of objectives and results within the agency’s entire area of responsibility and activities or within parts thereof. The evaluations shall focus on the appropriateness of, for instance, ownership, organisation and instruments, including grant schemes. The frequency and scope of the evaluations shall be based on the agency’s distinctive characteristics, its risk profile and its significance.»

The framework for the State’s exercise of ownership, as described in this white paper, is in accordance with the aforementioned provisions.

9.5.3 The OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises46

The OECD has adopted guidelines on corporate governance of companies with a state ownership interest (referred to as the SOE Guidelines) and for anti-corruption and integrity in companies with a state ownership interest (referred to as the ACI Guidelines). The guidelines contain recommendations concerning frameworks for state ownership and good corporate governance of companies with a state ownership interest. The guidelines are intended for the government authorities of the member states; however, by describing a set of good practices, they also provide guidance for the board and general manager of companies with a state ownership interest. The guidelines apply to companies with a state ownership interest that engage in economic activity,47 either exclusively or in combination with the pursuit of public policy goals.48

The SOE Guidelines aim to (i) professionalise the state as an owner, (ii) make companies with a state ownership interest operate with the same efficiency and the same degree of transparency as well-run private companies, and (iii) contribute to fair competition between companies with and without a state ownership interest. The guidelines are a supplement to the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance.49

The corporate governance guidelines state that the purpose of state ownership shall be to create value. The guidelines contain recommendations on the following main topics: rationales for state ownership, the state’s role as an owner, state-owned enterprises in the marketplace, equitable treatment of shareholders, responsible business conduct, transparency, and the responsibilities of the boards.

Key elements of the SOE Guidelines include recommendations relating to frameworks that promote fair competition when companies with a state ownership interest engage in economic activities. It is clear from the annotations to the guidelines that, when companies with a state ownership interest engage in economic activities, such activities must be carried out without any undue advantages or disadvantages relative to other companies. The overarching recommendation relating to fair competition (a level playing field) is elaborated on through several sub-recommendations, including that there should be a clear separation between the state’s ownership function and other state functions, transparency regarding cost and revenue structure for companies that combine economic activities and public policy goals, and that the companies shall, as a general rule, be subject to the same legislation as other companies and financing on market terms.

The ACI Guidelines supplement the SOE Guidelines by providing supplementary guidance to the member states on how to fulfil their role as active and informed owners in the specific area of anti-corruption and integrity. The ACI Guidelines include recommendations on how the member states should organise state ownership and promote integrity, as well as how the member states as owners should follow up the companies in relation to this.

The Norwegian State’s exercise of ownership is essentially in accordance with the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises.

9.5.4 The Norwegian Code of Practice for Corporate Governance

The Norwegian Corporate Governance Board (NCGB) consists of representatives of different interest groups for owners, issuers of shares and Oslo Stock Exchange.50 The Board prepares and updates the Norwegian Code of Practice for Corporate Governance. The objective of the Code of Practice is that companies listed in regulated markets shall have corporate governance that more comprehensively clarifies the division of roles between shareholders, the board and executive management than what is required by law. The Code of Practice is intended to strengthen confidence in the companies among shareholders, the capital market and other stakeholders.

The Code of Practice is primarily aimed at companies with shares listed in regulated markets in Norway, but is also relevant for unlisted companies. The Code of Practice chiefly addresses the companies’ boards; however, several of the recommendations are also relevant for owners. This includes recommendations 2 (Business), 3 (Equity and dividends), 4 (Equal treatment of shareholders), 5 (Shares and negotiability), 6 (General meetings), 7 (Nomination committee), 8 (Board of directors: composition and independence) and 11 (Remuneration of the board of directors). The Code of Practice is a supplement to the State’s own corporate governance principles.

9.6 Special framework conditions for companies that perform assignments for the State

The State awards assignments directly to several of the companies with a state ownership interest. This usually applies to companies in Category 2, but occasionally also to companies in Category 1. The awarding of such assignments is related to the State’s rationale for ownership and the State’s goal as an owner. The ability to award assignments directly to companies is regulated by the regulations for public procurements, the state aid regulations, the Regulations on Financial Management in Central Government and any special legislation applicable to the company. For companies that perform assignments for the State, the State will follow up the companies as the principal, regulatory authority and/or supervisory authority in addition to its capacity as owner. In such instances, the role played by the State should be clearly stated, see Chapter 12.8.

Examples of assignments the State can award to such companies include management of government schemes, construction and management of infrastructure, provision of goods and services and statutory monopolies. When the State instructs companies to perform assignments, the assignment is normally accompanied by financial compensation allocated via the national budget or through other regulated revenues.

The Regulations on Financial Management in Central Government can provide guidelines for the company’s performance of the assignment when concerning both funds transferred to the company and any State assets that the company manages. The State normally follows up assignments through letters of assignment/grant, reporting and dialogue, and, if applicable, goal and performance management systems.

The State can also enter into agreements to purchase services from a company. In such an event, the assignment and the financial compensation will normally be regulated in the agreement. Agreements are followed up through reporting from and dialogue with the company.

Companies with assignments from or agreements with the State can be fully or partly user-financed. The right of companies to charge a fee for goods or services, or exclusive rights to a market (monopoly), is adopted by the Storting.

Some companies may also have dedicated supervisory bodies charged with following up the assignments.51

Companies that engage in economic activities as defined in state aid law, in addition to having assignments or agreements financed by the public sector, must separate these activities in their accounts.52 Such a distinction highlights the company’s revenues and expenses, contributes to preventing illegal state aid through cross-subsidisation from non-commercial to commercial activities and allows for efficient supervision by the State as owner and principal/contracting party.

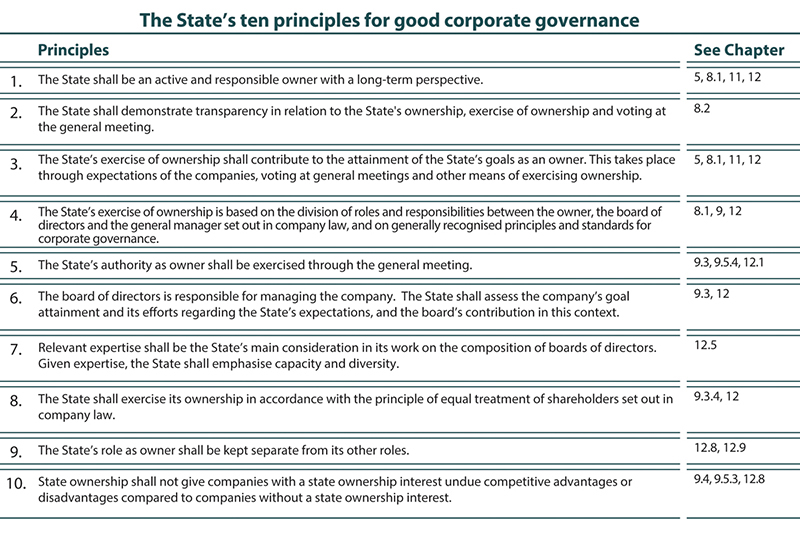

10 The State’s ten principles for good corporate governance

There has long been broad political consensus regarding the key framework conditions for the State’s exercise of ownership. This has created predictability for the companies and the capital market, which has been a strength of Norwegian State ownership. The key elements of the framework conditions for the State’s exercise of ownership are collated in the State’s ten principles for good corporate governance. The State’s principles for good corporate governance and the State’s goal as an owner together form the basis for how the State exercises its ownership within the framework conditions set out in Chapter 9.

In this white paper, the Government has clarified through Principle 1 that, in addition to being a responsible owner, the State shall also be an active owner with a long-term perspective.

As a responsible owner the State promotes responsibility in the companies. It is important for the State that the companies are managed responsibly, which entails acting in an ethical manner and identifying and managing the company’s impact on people, society and the environment.

The State being an active owner entails that the State shall contribute to the companies’ goal attainment within the framework conditions for the State’s exercise of ownership. The State achieves this by setting explicit goals as owner in each company, setting clear expectations of the companies, and actively following up the companies’ goal attainment and efforts regarding the State’s expectations. See Chapter 8.1 on how the State is an active owner.

The State having a long-term perspective as owner means that the State is focussed on the companies being managed in such a way that they achieve a high level of goal attainment in both the short and long term. This does not prevent the State from supporting or participating in transactions that can be expected to contribute to achieving the State’s goal as an owner, see Chapter 12.7.

Furthermore, it is specified in Principle 2 that the State shall be transparent about how it votes at general meetings.53 The State’s voting at general meetings has normally been available to the public by the companies publishing their minutes on their websites. Going forward, the State will actively publish its voting records unless special considerations dictate otherwise, for example, if publication could be detrimental to the company’s interests.

The principles are reflected in the State’s goal as an owner, the State’s expectations of the companies, how the State follows up the companies, including the State’s work on board elections, and how the State has organised the follow-up of the State’s ownership.

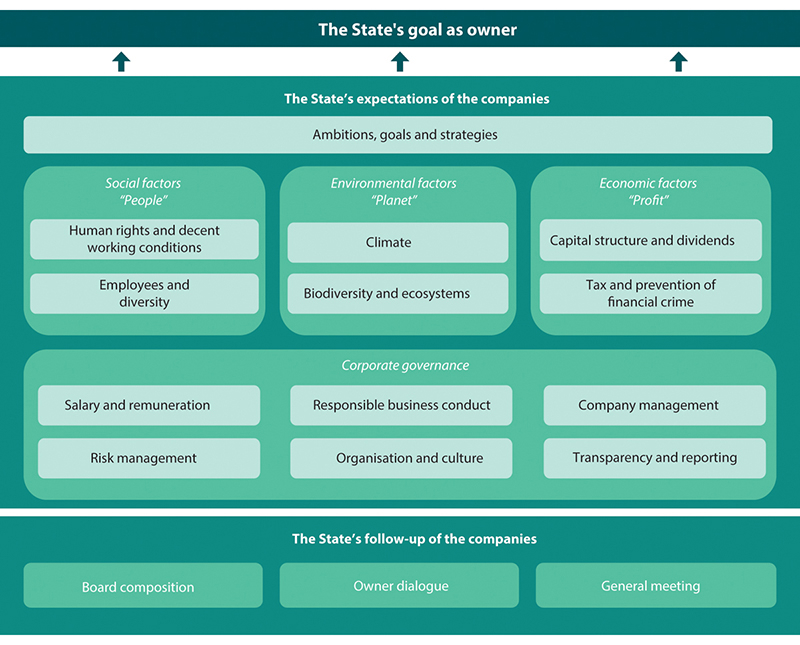

Figure 10.1 The State’s ten principles for good corporate governance.

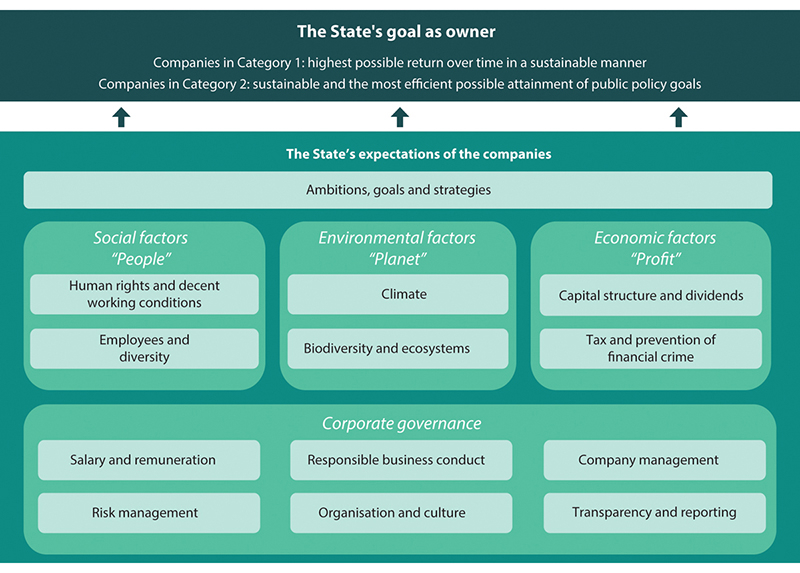

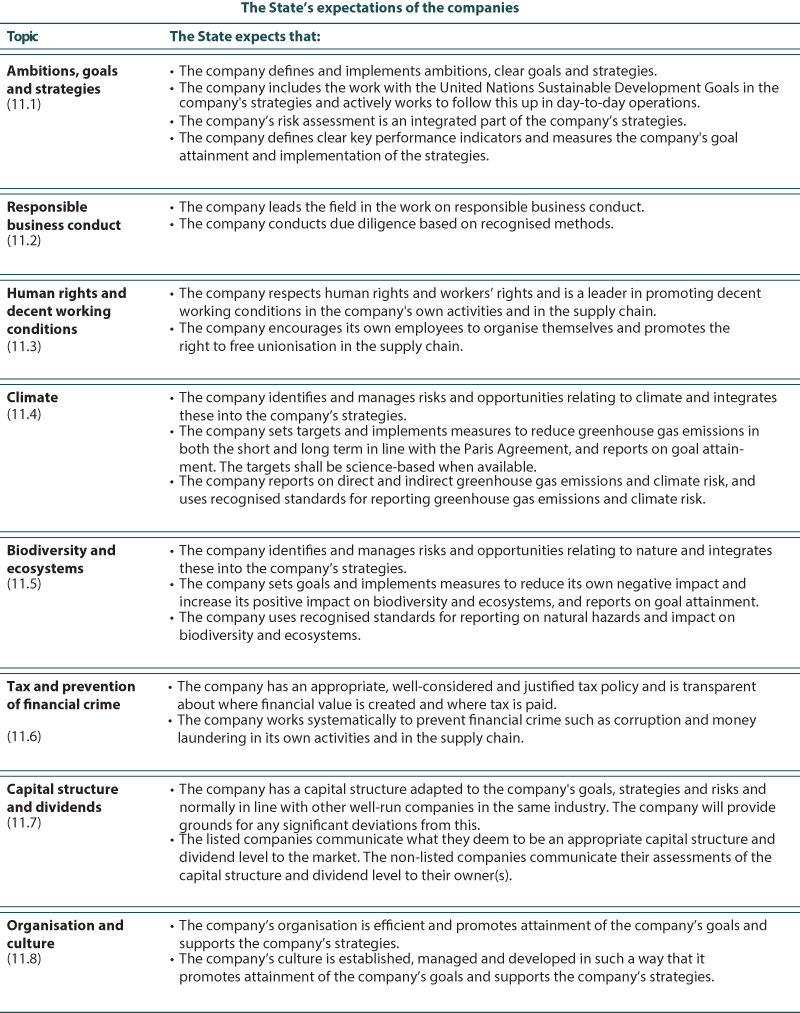

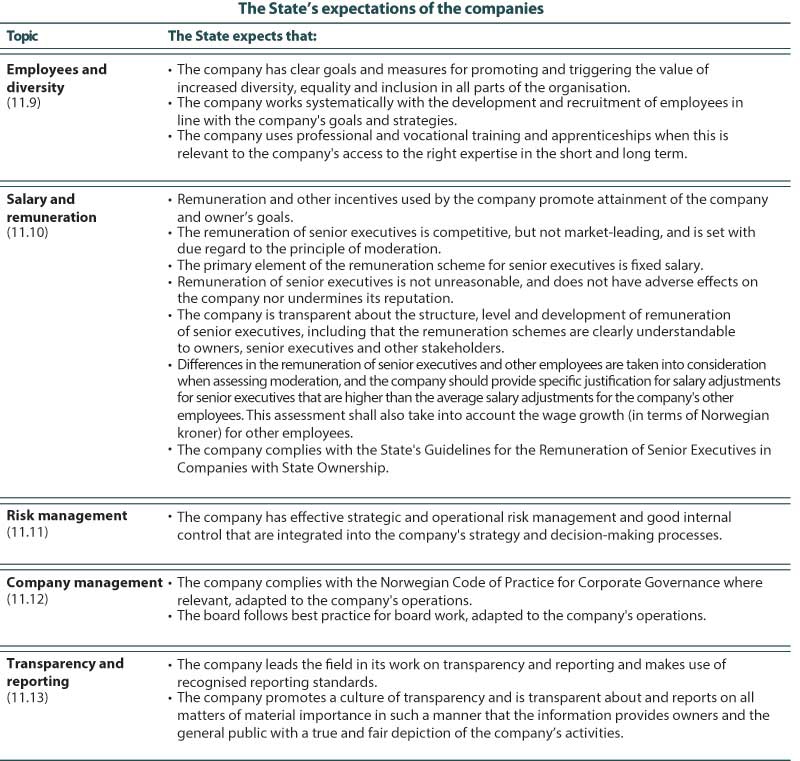

11 The State’s expectations of the companies

By defining clear expectations of the companies, the State wishes to be an active owner to contribute to attaining the State’s goal as an owner. Clear communication of the expectations also contributes to transparency regarding what is important to the State as an owner, and what the State will follow-up when exercising its ownership.

Pursuant to company law, the board is responsible for managing the company, while the general manager is responsible for the day-to-day management of the company’s activities. The State’s expectations as owner are communicated to the companies’ boards. For companies that are organised as groups, the expectations apply to the entire group.

Several of the State’s expectations are in areas where the specific work is normally followed up by the company’s day-to-day management (referred to as «management» in this chapter and Chapter 12). However, it is the board’s responsibility to assess how the company should emphasise and work with the various expectations and to follow up the work. The State assumes that the board is aware of the State’s expectations.

Unless otherwise specified, the expectations apply to all companies. Among other things, the companies differ in terms of their size, industry and international presence. The companies’ work within the different areas in which the State has expectations should be adapted to the companies’ distinctive nature, size, risk exposure and factors that are of importance for each individual company.

The State’s expectations are largely based on recognised guidelines, international good practice and the expectations of other leading investors.

The State’s goal as an owner for the companies in Category 1 is the highest possible return over time in a sustainable manner, and sustainable and the most efficient possible attainment of public policy goals for the companies in Category 2. Attainment of the State’s goals as owner presupposes that the companies consistently integrate financial, social and environmental factors into the companies’ ambitions, goals, strategies and corporate governance, see Figure 11.1. Common to all of the State’s expectations is that they shall contribute to the attainment of the State’s goal as owner.

Figure 11.1 The State’s expectations of the companies structured in accordance with financial (profit), social (people) and environmental factors (planet), as well as corporate governance.

The State’s expectations of the companies are set out in bullet points in this chapter. The expectations are summarised in Figures 11.10 and 11.11. The expectations are explained in more detail under the bullet points.

This chapter also describes good practice in selected areas as stated in separate boxes and figures. This serves as an inspiration for the companies’ work.

11.1 Ambitions, goals and strategies

The State expects that:

The company defines and implements ambitions, clear goals and strategies.

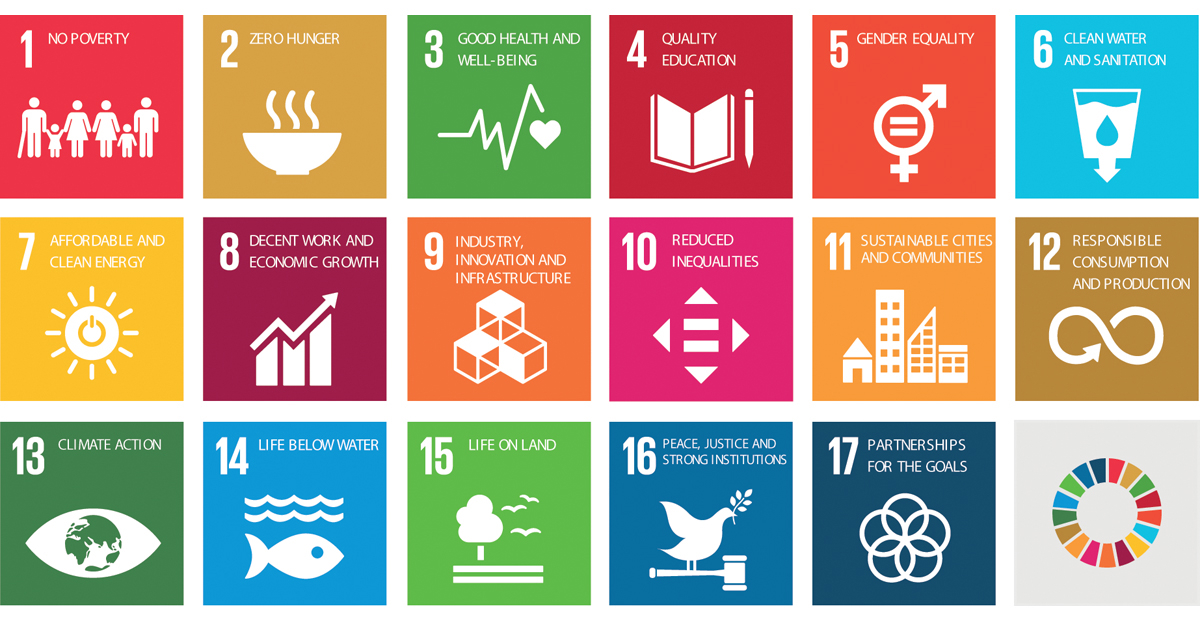

The company includes the work with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals in the company’s strategies and actively works to follow this up in day-to-day operations.

The company’s risk assessment is an integrated part of the company’s strategies.

The company defines clear key performance indicators and measures the company’s goal attainment and implementation of the strategies.

Ambitions, goals and strategies

The State places emphasis on the companies having an ambition, i.e. a view on the purpose of the company’s existence, beyond generating a return to the owners. In other words, a company’s ambition describes the company’s role in society, including the long-term benefit the company provides to its customers, local communities and other stakeholders. A well-defined ambition can provide direction for the company’s work with strategy, culture and long-term capital allocation. For the companies in Category 2, the company’s ambition and role in society will often follow from the State’s rationale for ownership and the State’s goal as owner.

It is important for the State that the board develops clear goals and strategies which present how the company will generate the highest possible return over time in a sustainable manner, or sustainable and the most efficient possible attainment of public policy goals. If a company in Category 2 also has activities that are in competition with others, it is important for the State that separate goals and strategies are defined for the public policy activities and activities that are in competition with others. Clear goals and strategies provide the company with direction and are expected to contribute to the company prioritising and allocating resources to areas that make the greatest contribution towards goal attainment. This includes how the company understands, protects and develops its competitive advantages and value drivers in both the short and long term.

For some companies, transactions and other structural measures may be appropriate for helping to achieve the State’s goal as owner. The State places an emphasis on the board having a conscious attitude towards and assessing these opportunities, and the State will consider any initiatives that are put forward.54

The board is responsible for setting ambitions, goals and strategies for the company within the framework of its articles of association. However, as a long-term owner, the State is focussed on engaging in dialogue with the company concerning this, including what underpins the company’s goals and strategies and how these are operationalised and followed up.

The highest possible return over time in a sustainable manner or sustainable and the most efficient possible attainment of public policy goals require the company to be sustainable. A sustainable company balances economic, social and environmental factors in a manner that contributes to long-term goal attainment without reducing the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Among other things, this entails that the company identifies and manages the opportunities and risks associated with sustainability and integrates these into the company’s strategies and corporate governance using materiality analyses.

Risks and opportunities associated with climate change and biodiversity are examples of value drivers that should be identified and managed in the companies’ strategy work. The State’s specific expectations in these areas are set out in Chapters 11.4 and 11.5.

The ability to adapt and innovate can be crucial to a company’s future development and goal attainment. Good innovation processes, the ability to identify and understand changes in the external environment and how these impact the company’s activities, as well as research and development, are normally vital for supporting the company’s strategy. For example, the company’s ability to develop and adopt circular business models and processes may be key to reducing risk and increasing opportunities for the company in the transition to a low-emission society.

Textbox 11.1 Circular economy

Stronger features of a circular economy are essential for achieving global climate goals and protecting nature, and constitute a strategic assessment for several companies. The extraction and use of natural resources has increased sharply over the past 20 years and is expected to double between 2015 and 2050.1

The essence of the circular economy is to retain the value of materials, products and resources that are in circulation in the economy for as long as practically possible and economically viable, and return these to the value chain at the end of the life cycle in order to, among other things, reduce the generation of waste. The transition to a more circular economy often requires that new means are found for meeting needs, that new and more sustainable products and business models are developed and that materials are used in new ways. For many companies, there are risks associated with linear value chains, and the transition to more circular value chains may be necessary for future access to input factors and continued operations. At the same time, more circular processes and business models can generate cost savings or create new competitive advantages and business opportunities.

1 The International Resource Panel (IRP).

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals are the global plan for sustainable development. The goals, which will apply until 2030, are intended to promote economic growth and eradicate poverty, combat inequality and stop climate change. The Sustainable Development Goals call for joint efforts by governments, civil society, academia and companies. Many companies have defined a selection of goals as being of key importance to their activities. Good practice for companies is to use the Sustainable Development Goals as a framework for integrating sustainability and responsible business conduct into the company’s strategies. This requires that the company familiarises itself with relevant sustainable development goals and associated targets, identifies how the company impacts and is impacted by these throughout the entire value chain and is open about this.

Figure 11.2 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

United Nations

Strategic risk assessment

When developing the company’s goals and strategies, it is crucial that the company exploits strategic opportunities, protects itself against threats and formulates plans based on risk capacity and risk appetite. Risk capacity depends on factors such as expertise, access to capital and other resources. Different goals and strategies means there are different risks, and determining how much and which types of risk the company is willing to accept is part of the board’s strategy work. The State expects that the company’s strategies are adapted in such a way that they are within the company’s risk capacity. In instances involving significant strategic investments, for example, when establishing activities in new geographical areas or in new or adjacent activities, it is essential to be aware of the consequences that the strategic choices will have for the company’s risk profile and whether it deviates from the company’s risk appetite and ability to manage this. A conscious risk assessment is an integral part of good strategy work and can be essential for the company’s goal attainment. The company’s transparency in this area is of vital importance to the State’s follow-up of its ownership, cf. also Chapter 11.13.

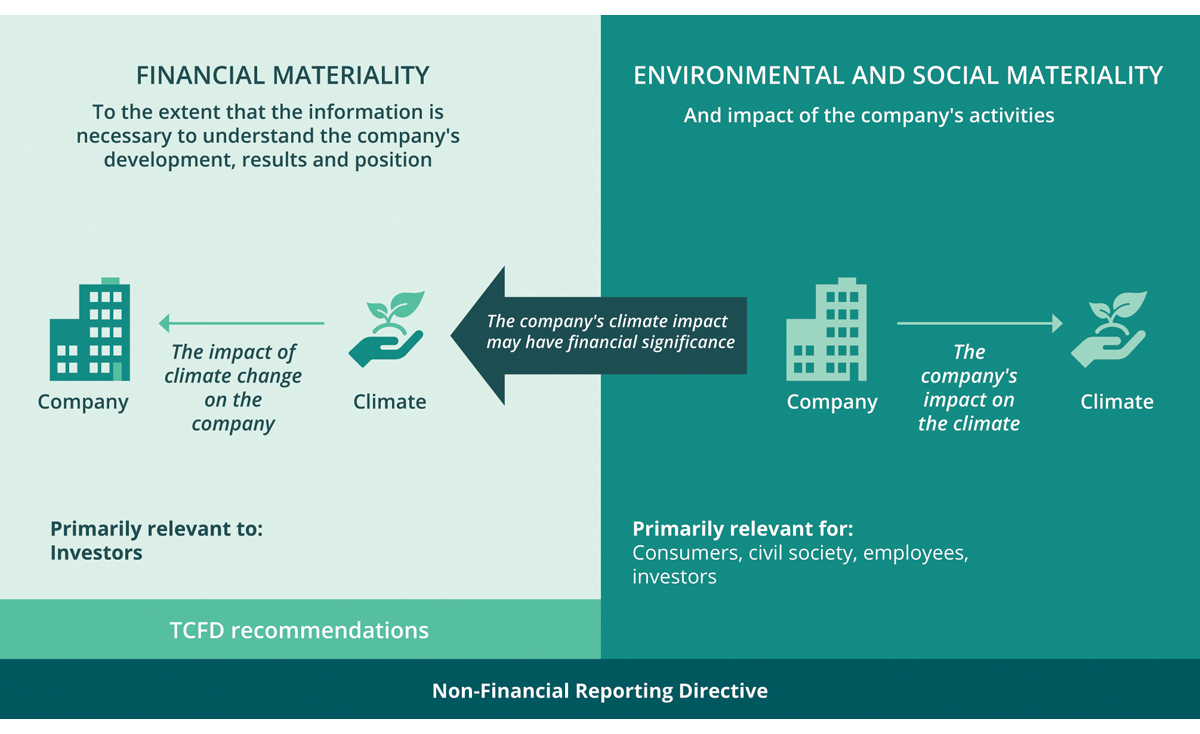

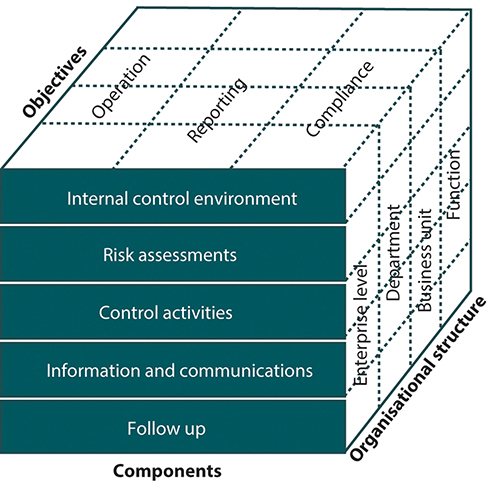

A good risk assessment includes a materiality analysis that follows the principle of double materiality in order to identify areas of significant risk and opportunity for the company, see Figure 11.3. This form of analysis addresses both the risk of changes and the impact that externalities have on the company and risks of the company’s activities impacting people, society and the environment. These risks can often overlap and good due diligence work dictates that both should be managed. A company that monitors developments in externalities, defines its role in society and understands the stakeholders and local community can better understand changes in, for example, customer preferences, the competitive situation and technology, and thereby what impacts the risk situation and opportunities for goal attainment.

The State engages in dialogue with the board regarding the company’s risk profile and whether the risk profile is balanced when based on the State’s rationale for ownership and the State’s goal as an owner when this is deemed relevant.

Figure 11.3 Principle of double materiality in the Non-Financial Reporting Directive

European Commission

Key performance indicators and measurement of goal attainment and implementation of the strategies

Of decisive importance to the company attaining its goals is that the strategy is implemented into its activities in a sound manner, for example, through action plans with clear milestones at relevant levels of the organisation.

The preparation of relevant key performance indicators55 can help in steering the company in the right direction, the implementation of strategies and better and fact-based decision-making. Good key performance indicators enable the owners, board and management to follow up the company’s goal attainment and measures.

Key performance indicators are defined for the areas that the company has identified as being of material importance and for which the company has set goals. Insights from the indicators are used to make fact-based decisions and to implement measures. It is of importance to the State that the most important key performance indicators relating to the company’s goals and strategy and action plans are consistently reported from the organisation to the board and owners. It is also relevant that the company reports on the development in goal attainment over time.

In order for the State, the board and management to be able to assess goal attainment for companies in Category 2, it is essential that these companies prepare goals, key performance indicators and target figures for both public policy goal attainment and efficient operations. Public policy goal attainment can be difficult to measure, and there may be a need to use additional key performance indicators, see Box 11.2. If companies in Category 2 also have activities that are in competition with others, it is essential that separate key performance indicators are prepared for this part of the company’s activities. For activities in competition with others, it will be relevant to implement target rates of return for the activities.

Textbox 11.2 Goals, strategies and key performance indicators for companies in Category 2

The Norwegian Agency for Public and Financial Management (DFØ) has developed a model for enterprises that have public policy goals, which is known as the result chain (resultatkjeden). This can be used to describe what is occurring in the enterprise and the consequences this has for users and society. The arrows in the model show the causal connections between the different boxes. The result chain can be used in the work with goals, strategies and key performance indicators. Goals, key performance indicators and target figures can be linked to the most important matters in the different boxes, which can form the basis for a hierarchy of goals.

Figure 11.4

DFØ (2010): Performance measurement – goal and performance management in the State.

11.2 Responsible business conduct

The State expects that:

The company leads the field in the work on responsible business conduct.

The company conducts due diligence based on recognised methods.

Leads the field in the work on responsible business conduct

To lead the field in the work on responsible business conduct entails acting in an ethically responsible manner and complying with best practice in this area at all times. This involves having good guidelines and systems for identifying and managing the potential and actual negative consequences the company’s activities have on people, society and environment. This includes both its own activities and the supply chain. The work is endorsed by the board and integrated into the company’s goals, strategies and other corporate governance. The work with responsible business conduct is adapted to the activities, distinctive characteristics, risk and size for each company.

To lead the field in the work on responsible business conduct also entails that the company complies with recognised guidelines such as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP), and the principles in the ILO’s core conventions. It also involves setting goals and implementing measures relating to responsible business conduct that have been identified as significant, as well as being transparent about goal attainment and using recognised reporting standards for transparency regarding sustainability and responsible business conduct, see Chapter 11.13. State-owned companies are of major public interest, and responsible business conduct helps to strengthen trust in and the legitimacy of the companies.

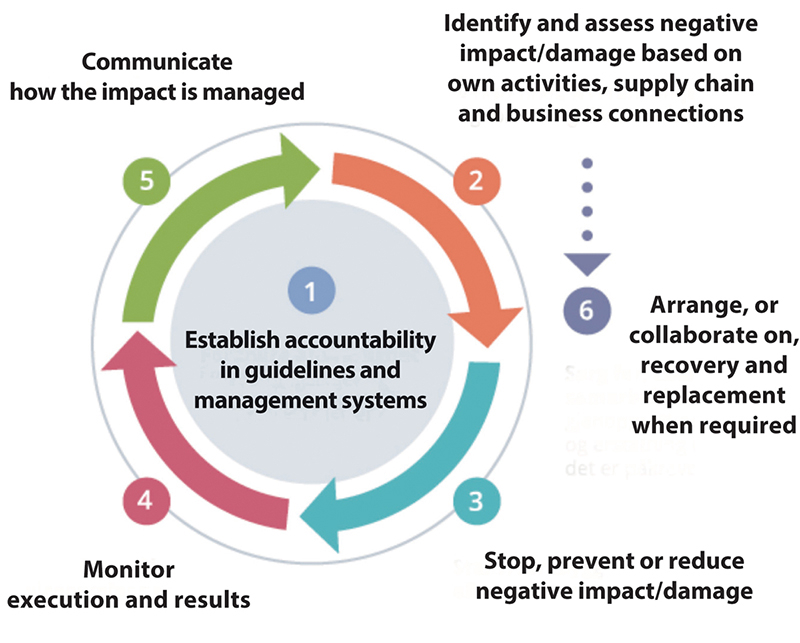

Conduct due diligence

Due diligence assessments are carried out in accordance with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) and the OECD Due Diligence Guidance. This involves identifying, preventing and limiting, as well as explaining how the company manages the actual and potential negative impact or harm its activities have on people, society and the environment. Due diligence assessments also include having systems in place to rectify any negative impact or harm that is caused by the company.

A number of countries have included requirements for the implementation of due diligence assessments in their national laws. Norway has adopted the Act relating to enterprises’ transparency and work on fundamental human rights and decent working conditions (Transparency Act). The Act requires large enterprises to carry out due diligence assessments related to fundamental human rights and decent working conditions in their own activities and in the supply chain, and to provide an annual report on this work. The Act applies irrespective of where the company carries out its activities. In the spring of 2022, the European Commission submitted a proposed directive that, if adopted, will require larger companies to conduct due diligence assessments of both human rights and key environmental aspects.56 The State’s expectation that the company conducts due diligence assessments in accordance with recognised methods such as the OECD Due Diligence Guidance is thematically broader than the scope of the Transparency Act, since, in addition to human rights and decent working conditions, it also covers matters relating to, among other things, climate and nature, as well as corruption. The OECD Due Diligence Guidance is summarised in Figure 11.5.

Due diligence assessments are risk-based and involve prioritisation, which means that the risks that are assumed to be the most serious are prioritised first. Due diligence assessments depend on context, which in some cases will require particularly in-depth assessments. Good systems and routines are therefore of key importance, including for evaluating and improving the company’s due diligence assessments. The work on due diligence assessments is endorsed by the board and integrated into the company’s goals, strategies and guidelines.

Due diligence assessments require the company to have a meaningful dialogue with stakeholders, with particular emphasis on those who are or may be adversely affected by the company’s activities. Different stakeholder groups, for example, children, women and indigenous peoples, may have different perceptions of how they are or may be adversely affected by the company’s activities. It will therefore be relevant for many companies to pay particular attention to the rights of these groups in their due diligence assessments. See also the expectations regarding human rights and decent working conditions in Chapter 11.3.

Figure 11.5 OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct.

OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct.

11.3 Human rights and decent working conditions

The State expects that:

The company respects human rights and workers’ rights and is a leader in promoting decent working conditions in the company’s own activities and in the supply chain.

The company encourages its own employees to organise themselves and promotes the right to free unionisation in the supply chain.

Respect human rights and workers’ rights and be a leader in promoting decent working conditions.

International human rights and workers’ rights are rooted in key UN conventions and ILO’s core conventions, see Box 11.3. The rights that are considered to be the most important will vary for different companies and are identified through due diligence assessments, see Chapter 11.2.

Respecting human rights and workers’ rights entails that the company works in accordance with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP), ILO’s core conventions and relevant chapters in the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, cf. Chapter 11.2. This applies both to the company’s own activities and the entire supply chain. Larger companies have statutory duties under the Transparency Act.

It is also of importance to the State that companies which operate in, trade with or have business contacts linked to conflict areas57 demonstrate respect for international humanitarian law58 and avoid contributing to, or supporting violations of these rules. Instances such as these require particularly extensive due diligence assessments.59

Among other things, leading the field in the work for decent working conditions means working systematically with health, safety and the environment (HSE) in the workplace and that employees in their own activities and in the supply chain are paid a living wage.

Unionisation

The right to organise and collective bargaining is a key part of the ILO’s core conventions and the Norwegian model. It is important for the State that the company encourages its own employees to unionise, and that the company applies its respect for employees, trade unions and participation in its international activities and to its business contacts. For companies with international activities, this may include entering into global framework agreements.

Textbox 11.3 Human rights and ILO conventions

Human rights conventions

The United Nations human rights norms consists of nine key UN conventions.1 Together with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights constitute the core of the international human rights conventions and set out the normative standard that companies should, as a minimum, use as a basis for their due diligence assessments. Other key conventions for companies’ due diligence assessments include the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women, and ILO Convention 169 concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries.

The ILO’s core conventions

The ILO’s conventions and recommendations set minimum standards for the labour market. The ILO’s ten core conventions constitute minimum rights to be respected in the labour market, and are divided into four main categories: freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining, prohibition of child labour, prohibition of forced labour and prohibition of discrimination.

The ILO’s ten core conventions:

1. Convention No. 87 on the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise (1948).

2. Convention No. 98 on the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining (1949).

3. Convention No. 29 on Forced Labour (1930) and Protocol to Convention No. 29 on Forced Labour (2014).

4. Convention No. 105 on the Abolition of Forced Labour Convention (1957).

5. Convention No. 138 on the Minimum Age for Admission to Employment (1973).

6. Convention No. 182 on the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labour (1999).

7. Convention No. 100 on Equal Remuneration for Men and Women Workers for Work of Equal Value (1951).

8. Convention No. 111 on the Discrimination in Respect of Employment and Occupation (1958).

9. Convention No. 155 on Occupational Safety and Health and the Working Environment (1981).

10. Convention No. 187 on the promotional framework for occupational safety and health (2006).

1 For information regarding the United Nations conventions see (https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/human-rights).

11.4 Climate

The State expects that:

The company identifies and manages risks and opportunities relating to climate and integrates these into the company’s strategies.

The company sets targets and implements measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in both the short and long term in line with the Paris Agreement, and reports on goal attainment. The targets shall be science-based when available.

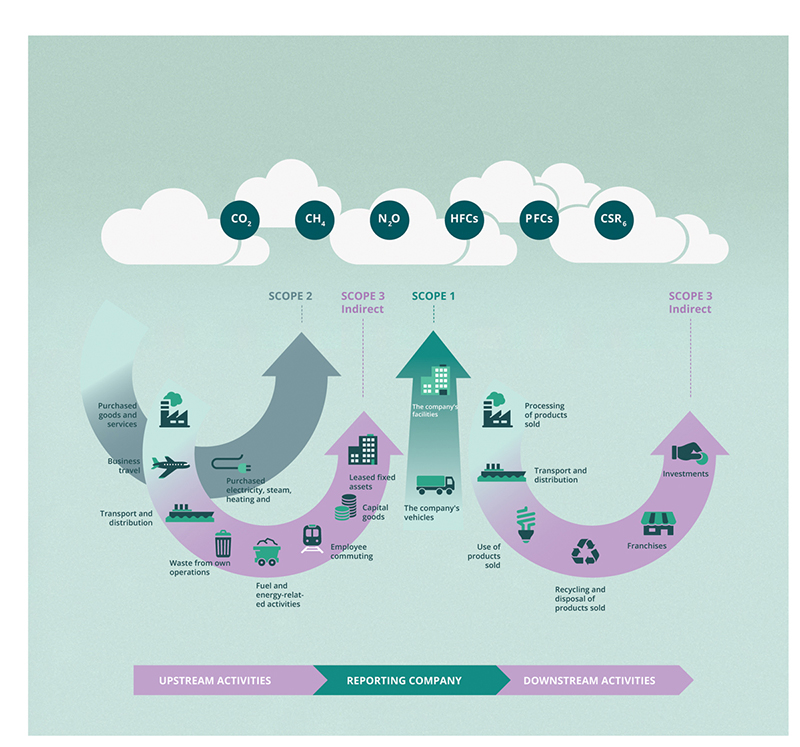

The company reports on direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions and climate risk, and uses recognised standards for reporting greenhouse gas emissions and climate risk.

Identifies and manages risks and opportunities related to climate

It is essential for the companies’ future goal attainment that they succeed in the transition to a low-emission society. The Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting the increase in temperatures will require global CO2 emissions to be reduced to net zero by 2050. An orderly and sufficiently rapid restructuring process that is in line with this can contribute to lower risk and costs for the company, owners and society at large when compared with other scenarios.