3 The private sector’s role and responsibilities

Figure 3.1

The private sector’s primary aim is value creation. By creating value, it contributes to economic growth and social development. In a long-term perspective, it is in the interests of both companies and society to have a private sector that operates responsibly and develops products and services that help address social and environmental challenges.

Globalisation, with its attendant advances in communication technology and increased transparency, has led to greater awareness concerning the challenges companies face with regard to social development. A growing number of consumers, clients and investors are demanding that products and services are produced in a manner that is socially and environmentally sound. For companies, it is a matter of developing their «social antennae» and having the ability to internalise aspects of social development in their own operations. However, the situations that companies encounter internationally not only pose challenges; they also present opportunities. Through novel ways of thinking and innovation, companies can discover new market opportunities.

Companies that exercise social responsibility can reduce their own risks, which can positively impact their competitiveness and financial development. Norwegian companies operating abroad are often equated with the Norwegian state, and their conduct is therefore also important for Norway’s reputation.

3.1 Expectations of the private sector

The Government expects all companies to exercise social responsibility, irrespective of whether they are privately or publicly owned. The Government’s position is that Norwegian businesses should be at the forefront when it comes to practising social responsibility based on sound values, awareness and reflection. Norwegian companies should pursue best practices within their field or branch as their guiding principle and aim when developing their CSR efforts.

3.1.1 Guidelines for social responsibility

The Government expects all Norwegian companies to develop and comply with guidelines for social responsibility. Companies’ employees – and, as far as possible, their partners in the supply chain – should be familiar with these guidelines.

There are a number of international guidelines for CSR, which are discussed in detail in Chapter 6. The Government would like to draw particular attention to the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. These guidelines provide a detailed framework of principles and standards for responsible business conduct consistent with applicable laws. As an adhering country, Norway is obligated to encourage its private sector to observe the Guidelines. The Government expects Norwegian companies to acquaint themselves with the Guidelines, and to follow them in their operations.

The UN has also developed principles for responsible business practices through the Global Compact initiative. The UN Global Compact seeks to advance 10 principles in the areas of human rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption. It is based on international conventions and guidelines. Companies that have joined the Global Compact are expected to implement the principles in their business operations, share their experience, and report on the progress they have made in implementing the 10 principles. In the Government’s view, participation in networks such as the UN Global Compact can enable companies to increase their knowledge and enhance their motivation to exercise social responsibility.

3.1.2 Good corporate practices

The Government expects Norwegian companies to promote good corporate practices from Norway in their operations abroad. CSR efforts must be integrated into their operations, and followed up on an ongoing basis by management. Systematic CSR efforts should have the firm backing of company boards. They should be developed and practised in close cooperation with employees and employee representatives, and in dialogue with suppliers, clients and other stakeholders. They must form an integral part of companies’ day-to-day corporate governance.

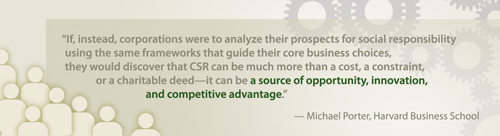

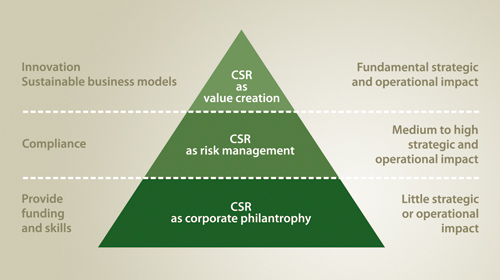

Figure 3.2 Three different understandings of CSR.

Source The UN Global Compact.

The Government considers it important for companies to involve the trade union movement in their CSR efforts. Since employee representation on company boards is generally only found in the Nordic countries, it is crucial that employee representatives in other countries are also drawn into these efforts. Global framework agreements entered into between Norwegian multinational enterprises and international labour organisations are a good example of how Norwegian companies can work at the corporate level, cf. Box 3.6.

At the same time it is important to be aware that, in many contexts, Norwegian experience and practices cannot simply be transferred to other countries uncritically. It is important that Norwegian companies are open to, and respect, cultural and value differences, and that they seek to find ways of adapting elements of Norwegian corporate practices to other countries.

Systematic CSR efforts are a key element of the risk management and business strategies of forward-looking companies. In this context, it is also important to have systems and routines for whistle-blowing or notification of unacceptable conditions. The Norwegian Working Environment Act has been amended to include new provisions concerning employees’ freedom of expression, and came into force on 1 January 2007. Employers are to develop routines for notification or whistle-blowing inside the company, or implement measures that facilitate notification concerning unacceptable circumstances in the company.

Norwegian companies should also establish routines for notification and whistle-blowing for their activities abroad so that employees can report unacceptable circumstances or seek advice and guidance. This could for example be done by appointing an ombudsman within the company, using an external arrangement or tasking an existing body to fulfil this function.

Textbox 3.1 Main elements of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises

Concepts and Principles:The Guidelines set out voluntary principles and standards of good practice for all enterprises, and they have global relevance.

General Policies: Enterprises should take fully into account established policies in the countries in which they operate, and they should respect human rights, promote local capacity building and encourage suppliers and sub-contractors to apply principles of corporate conduct compatible with the Guidelines.

Disclosure: The Guidelines recommend regular disclosure of information regarding enterprises’ activities, structure, financial situation and performance.

Employment and Industrial Relations: Enterprises should respect the their employees’ labour rights, engage in constructive negotiations with employees’ representatives, combat discrimination, and contribute to the elimination of child labour and forced or compulsory labour.

Environment: Enterprises should take due account of the need to protect the environment and public health and safety. They should establish a system of environmental management, and maintain contingency plans for preventing, mitigating, and controlling serious environmental and health damage.

Combating Bribery:Enterprises should not, directly or indirectly, offer, promise, give or demand a bribe or other undue advantage to obtain or retain business or other improper advantage. They should promote employee awareness of company policies against bribery.

Consumer Interests:Enterprises should act in accordance with fair business, marketing and advertising practices and should take all reasonable steps to ensure the safety and quality of the goods or services they provide. They should provide consumers with product information and establish procedures that contribute to the resolution of consumer disputes.

Science and Technology: Enterprises should contribute to the transfer of technology and know-how to host countries and to the development of local and national innovative capacity. When appropriate, they should perform science and technology development work in host countries.

Competition: Enterprises should refrain from entering into or carrying out anti-competitive agreements among competitors, and should conduct all their activities in a manner consistent with all applicable competition laws.

Taxation: Enterprises should contribute to the public finances of host countries by making timely payment of their tax liabilities.

3.1.3 Transparency and disclosure

In the Government’s view, it is important that companies demonstrate transparency and disclose information about social and environmental factors in connection with their operations, cf. Chapter 8, section 3. This helps to forge trust and good relations with the societies in which companies are operating. It can be important for stakeholders to know what guidelines the companies use as the basis for their activities and how these are followed in practice. This applies to shareholders, authorities, employees, clients, suppliers, partners and society at large.

As part of their transparency efforts, it is important that companies report on their social and environmental performance, either in separate reports or in their ordinary annual reports. Systematic reporting can be an important tool in developing companies’ CSR practices. It can also help to improve companies’ risk management capability.

Reporting based on a common standard facilitates the comparison of results. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) has developed a framework for reporting on economic, environmental and social performance, which provides an internationally recognised standard for reporting. The GRI Reporting Framework is particularly suitable for large-scale enterprises, but small and medium-sized enterprises can use relevant parts of the framework flexibly, cf. Chapter 6, section 3. Companies can enhance the credibility of their reports through external auditing carried out by impartial groups or individuals.

3.1.4 Vigilance and knowledge sharing

In the Government’s view, companies should be vigilant and actively seek out information about social conditions and trends in the areas where they are operating. They should adopt a holistic approach that takes into account the challenges and dilemmas they face in their international operations. Fostering openness and engaging in dialogue with the communities in which they operate are prerequisites for finding good solutions. The Government expects companies to be particularly vigilant when operating in vulnerable or conflict-affected areas. This is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4.

Companies should actively gather information, draw on the experience of other companies that engage in systematic CSR efforts, participate in networks or seek other ways of benefiting from the transfer of knowledge and expertise. They should also be willing to share their knowledge with other companies, particularly small enterprises that have limited experience of international operations. It can also prove fruitful for companies to cooperate with NGOs that have knowledge and experience of the situation in the host country. Companies that are at an early stage in integrating CSR into their operations should contact organisations and institutions that can provide information, guidance and expertise, cf. Chapter 9.

3.1.5 Innovation and social responsibility

The ability to convert good ideas into new solutions has never been more important for achieving positive social development and business success. Innovation is the key to competitiveness, value creation and sustainable growth for companies and countries alike. Innovation in the private sector is also essential in addressing the challenges of our time. By developing new products and services, technology, production processes, forms of organisation, business models and partnership models, the private sector can help to meet the challenges facing society.

Figure 3.3 The first female solar panel engineer in India’s largest state, Rajasthan.

Source Robert Wallis/Panos Pictures/Felix Features.

Today Norwegian companies’ competitive advantage lies primarily in production that is based on the natural environment and natural resources or that is knowledge-intensive, or a combination of the two. Norway has considerable potential for further developing knowledge-based industries, for example in areas such as energy, the environment, and maritime and marine activities. Because Norway is a high-cost country and natural resources are limited, it will be difficult in the long term for the Norwegian private sector to maintain a competitive advantage that is not based on knowledge and innovation.

Textbox 3.2 Renewable Energy Corporation (REC)

There is a great deal of innovation taking place in Norwegian energy companies in connection with the development of new technology. In the international solar cell industry, two new processes for the production of high-purity silicon have been developed. Both of these are Norwegian, or Norwegian-owned.

The Renewable Energy Corporation (REC) is currently one of the world’s leading solar energy companies, specialising in silicon materials, photovoltaic wafers, solar cells and solar modules. Solar power plants using the REC’s newest modules are expected to pay back the energy used in their manufacture in the course of about a year. Access to clean and climate-friendly energy at affordable prices for people all over the world would be an important contribution to sustainable development.

By developing technology and reducing costs, solar energy could quickly become a competitive alternative to less sustainable forms of energy.

Innovation and the ability to adapt are key to tackling social challenges relating to the environment, the growing number of people requiring care, and increased globalisation. The Government will therefore seek to facilitate greater innovation in both the private and the public sectors. In this connection, it submitted a white paper on innovation to the Storting in 2008. The white paper sets out the Government’s policy for securing long-term and sustainable value creation.

The Government expects Norwegian companies to:

integrate a clear awareness of CSR in their boards, management teams and corporate culture;

build and further develop the necessary expertise within the company;

acquaint themselves with the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and follow them in their operations;

consider joining the UN Global Compact;

draw up and implement guidelines for social responsibility;

follow their own guidelines with regard to the supply chain, by setting requirements, having control procedures and promoting capacity-building;

take good corporate practices with them from Norway, including models for cooperating with employees and employee representatives;

develop their own CSR standards, using best practice within their field or branch as their guiding principle and goal;

establish mechanisms or schemes for whistle-blowing or notification of unacceptable circumstances;

show transparency with regard to the economic, social and environmental consequences of their operations;

actively seek out information and guidance in connection with international operations, particularly in developing countries.

3.2 The responsibility of business in key areas

3.2.1 Corporate responsibility to respect human rights

The involvement of various actors is necessary in order to ensure greater respect for human rights at the national and international level. Companies’ attitudes and conduct are crucial in this context. Leading companies have gradually gained a greater awareness of human rights, as well as of the significance that better observance of these rights in the host country can have for companies and their stakeholders.

Textbox 3.3 Key human rights conventions

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

The UN Convention Against Torture

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

The UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

The European Convention on Human Rights

The European Social Charter

The European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

The ILO core conventions

Human rights constitute a set of obligations that are not directed towards the private sector. They are formulated as the obligations of a state towards its citizens, and they must be safeguarded by the public authorities. At the same time, it can be argued that human rights are an expression of general moral obligations that apply to all members of society. This conception is reflected in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the UN in 1948.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights covers civil and political rights, as well as economic, social and cultural rights. The different kinds of rights have been defined more precisely and codified in a number of international human rights conventions.

According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, everyone has an individual responsibility in relation to human rights. Human rights are therefore relevant for companies and business managers too, albeit in a different way than they are for states. Companies can fulfil this obligation by acting in a responsible manner, irrespective of where they are operating.

In many countries, the authorities are directly responsible for gross human rights violations. This may be a case of the police systematically using torture, or of dissidents being imprisoned without trial. In other countries, the authorities fail to enforce provisions intended to protect employees or consumers, for example the prohibition of child labour or provisions concerning a minimum wage.

Textbox 3.4 The NHO checklist on human rights from the perspective of business and industry

The Confederation of Norwegian Business and Industry (NHO) has, in collaboration with Amnesty International, drawn up a checklist that can be used in connection with Norwegian companies’ assessments in connection with operations abroad. The checklist is based on the UN Universal Declaration of Human rights, and gives companies concrete guidance on dealing with challenges related to human rights. The checklist includes the following questions:

Does the company have guidelines that prohibit discrimination based on race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status?

Does the company have guidelines that ensure safe and healthy working conditions for employees, and are the rules observed?

Does the company have procedures that prevent slavery, forced child labour or hard labour performed by prisoners?

Does the company have guidelines that ensure employees’ right to enter into collective agreements, including their right to strike?

Companies have a duty to comply with national statutory provisions concerning human rights in the countries in which they operate. A violation of these provisions may entail legal liability in the country concerned. The question is whether or not companies have a responsibility beyond this, in particular in relation to the communities over which they have influence or control. This is a relevant issue in international forums.

In light of this, the UN Secretary-General appointed a Special Representative on business and human rights in 2005, with the mandate to examine the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises. The Special Representative has carried out broad consultations and important surveys and studies concerning these questions. A final report was submitted to the UN Human Rights Council in April 2008. In the report, a conceptual and policy framework is presented, which comprises three core principles:

The State duty to protect against human rights abuses by third parties, including business;

The corporate responsibility to respect human rights; and

The need for more effective access to remedies.

The Special Representative’s mandate was renewed in June 2008 in order to operationalise this framework and provide concrete recommendations. The Special Representative’s efforts in the time ahead are expected to form the basis for the international debate in the coming years, cf. Chapter 7, section 1. Norway is actively involved in these efforts.

3.2.2 Corporate responsibility to provide decent work

Although the main responsibility for regulating the working environment lies with the authorities of the countries concerned, the private sector has an independent responsibility for working conditions in its own activities. Companies’ obligations to respect and promote human rights include creating decent working conditions where fundamental labour standards are complied with and employees receive a living wage.

Companies are expected to be familiar with national legislation and international conventions relating to working conditions. The ILO core conventions are of central importance in this context. Companies should consider whether or not it is sufficient to comply with the legislation of the countries in which they are operating. At a minimum, they should ensure that workers’ rights and working conditions are in line with the standards set out in the ILO core conventions.

Figure 3.4 Children working at a brick manufacturing plant in Peru on the World Day Against Child Labour, 12 June 2008.

Source EPA/PACO CHUQUIURE/Scanpix.

The eight ILO core conventions are considered to be fundamental to rights at work. They cover what are known as the fundamental principles and rights at work: freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining (including the right to strike); the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour; the effective abolition of child labour; and the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

Textbox 3.5 The ILO core conventions

Convention concerning Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise, 1948 (No. 87);

Convention concerning the Application of the Principles of the Right to Organise and to Bargain Collectively, 1949 (No. 98);

Convention concerning Forced or Compulsory Labour, 1930 (No. 29);

Convention concerning the Abolition of Forced Labour,1957 (No. 105);

Convention concerning Minimum Age for Admission to Employment, 1973 (No. 138);

Convention concerning the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labour, 1999 (No. 182);

Convention concerning Discrimination in Respect of Employment and Occupation, 1958 (No. 111);

Convention concerning Equal Remuneration for Men and Women Workers for Work of Equal Value, 1951 (No. 100).

The right to equal pay for equal work and for work of equal value is set out in ILO Convention No. 100 and in the Norwegian Gender Equality Act. In addition to pay, anti-discrimination standards also cover employment, promotion and opportunities for development at work.

The purpose of the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (1977) is to encourage companies, national authorities and the social partners to promote decent working conditions and social dialogue at the workplace. It lays down principles in the areas of employment, training, conditions of work and life, and industrial relations. The Declaration was amended in 2000 and again in 2006 in accordance with other ILO instruments. The ILO Governing Body has set up a helpdesk to provide managers and employees with information about the Declaration.

Textbox 3.6 Global framework agreements

A number of companies have entered into global framework agreements with labour organisations that are to apply to their operations worldwide. In general, these agreements are between international workers’ organisations and multinational enterprises. Altogether there are currently some 50 agreements of this kind, covering more than 4.2 million workers.

The agreements are generally based on the ILO core conventions and refer to them directly. Respect for labour rights is an important element in the agreements. In addition, the agreements often ensure a minimum level of protection for workers with regard to health, safety, working environment, pay and working hours. Mechanisms have also been included for monitoring and following up the agreements. A few of the agreements also oblige companies to enter into similar agreements with their subcontractors.

The paper manufacturer Norske Skog has signed an agreement with the International Federation of Chemical, Energy, Mine and General Workers’ Unions (ICEM), which sets out minimum standards for working conditions, health and safety, and human rights. Other Norwegian companies that have entered into agreements of this kind include Aker ASA, StatoilHydro and Veidekke.

Many Norwegian companies have developed guidelines designed to ensure that workers’ rights are respected by both their subsidiaries and subcontractors. It is also important that the companies have effective follow-up and control mechanisms that ensure compliance with the guidelines. Many companies still need to establish good guidelines and practices in this area, not least when it comes to encouraging their subcontractors to respect employees’ rights. This can be achieved by including clauses in their contracts with their subcontractors, for instance.

3.2.3 Corporate environmental responsibility

The Government views the participation of the private sector as crucial in addressing the challenges relating to climate change, the loss of biodiversity, and releases of hazardous substances. Companies that manage to stay at the forefront of innovation and environmentally sound resource use can gain comparative advantages, both in financial terms and in relation to markets. The focus of corporate environmental responsibility has shifted from avoiding damage to the environment to integrating environmental concerns and resource use into systems for managing companies’ products, finances and reputation.

Textbox 3.7 Carbon Disclosure Project

The Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) is an independent, non-profit organisation that collects and publishes information on corporate greenhouse gas emissions, as well as other information on how companies are managing and reducing their greenhouse gas emissions. Altogether, 1 300 of the world’s largest companies responded to the CDP questionnaire in 2007.

The CDP Corporate Supply Chain Programme was initiated in 2007. The aim of the programme is to establish a standardised approach to the reporting of greenhouse gas emissions resulting from a company’s supply chain emissions. Participating Norwegian enterprises include Aker Yards, DnB Nor, Hafslund, Marine Harvest Group, Norsk Hydro, Orkla, the REC Group, Schibsted, StatoilHydro, Storebrand and Norges Bank.

Under international agreements that have been implemented in national legislation, the private sector must comply with a number of requirements designed to limit the adverse environmental impacts of its operations. Multilateral environmental agreements are incorporated into national legislation on an ongoing basis, and thus form part of the existing legislation that companies must comply with in countries that are parties to these agreements.

In addition to the ongoing development of national and international environmental standards for the private sector, companies should take a proactive approach in order to reduce the adverse environmental impacts of their operations beyond what is stipulated in such standards. By being at the forefront of developments in this area, companies can achieve lower costs, an improved strategic starting point for their long-term operations, and new market opportunities. The private sector should therefore have considerable self-interest in integrating an environmental perspective more fully into its activities.

The private sector can help to mitigate environmental problems by making its own operations more environmentally friendly and by making efficient use of resources. Companies can play a part by developing innovative processes or technology designed to minimise the use of scarce resources and reduce harmful emissions. Companies can also develop new, greener products and services to replace existing ones. They can make an important contribution by collaborating with their supply chains and requiring their partners to meet high environmental standards. The most advanced companies now carry out life cycle analyses for their products, and are introducing routines that include requirements for their subcontractors.

Climate change is creating new challenges, and national authorities and the private sector have a shared responsibility for addressing them. The authorities are responsible for establishing a framework that will promote innovation and cost-effective solutions. The private sector has a role to play in finding solutions by developing new technology and by using the best available techniques. It is important to raise companies’ awareness of their direct and indirect impacts on the climate, and what steps they can take to minimise these impacts.

3.2.4 Corporate responsibility to combat corruption

Corruption is a serious obstacle to social and economic development in many parts of the world. Total international development assistance is insignificant compared with the sums that disappear from poor countries, for example due to corruption and tax evasion. Public corruption and the unlawful enrichment of decision-makers undermine democratic processes and decisions based on the best interests of the community. Valuable resources are lost, and public governance is weakened.

There are various forms of corruption, ranging from corruption linked to large-scale projects with substantial flows of capital, to grease or lubrication payments and facilitation payments. There is a close connection between corruption, other forms of international crime, and illicit financial flows.

Like many other countries, Norway is party to various international agreements that contain obligations to combat corruption. These obligations define the conditions for business activity both within and outside Norway’s borders.

Figure 3.5

Source Jocelyn Carlin/Panos/Felix Features.

Norwegian legislation relating to corruption has been made more stringent in recent years. This is particularly evident in the amendments to the Penal Code. All forms of corruption are prohibited under Norwegian law. This prohibition also applies fully to Norwegian nationals and persons domiciled in Norway who are involved in activities abroad. Facilitation payments, i.e. payments for services to which one is already entitled without paying an extra fee, are also considered to be corruption. The key concept in the legislation is that of «improper advantage».

Norwegian courts base their rulings on Norwegian law, even when business has been conducted abroad. However, the culture and traditions of the country in question are taken into account when assessing to what extent improper conduct has occurred. Companies may incur criminal liability under foreign legislation, as well as under Norwegian legislation. Companies therefore have to observe both local and Norwegian laws.

The Penal Code includes three sections that are particularly important in the fight against corruption. These are: section 276a, on corruption; section 276b, on gross corruption; and section 276c, on trading in influence (see Box 3.8). Those convicted of corruption face up to three years’ imprisonment, while the penalty for gross corruption is imprisonment for up to 10 years. Aiding and abetting carries the same penalty.

According to the amendments of 1 March 2008 to the Act relating to compensation, corruption also incurs liability for damages. If an employer is to avoid liability for damages caused by an employee’s corrupt behaviour, the employer must have taken all reasonable precautions in order to prevent corruption of this kind from occurring.

A growing number of other countries are tightening their legislation on corruption, partly as a result of the UN Convention against Corruption, the Council of Europe Criminal Law Convention on Corruption, and the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention. This means that the international community is moving towards a global standard. For Norwegian companies operating in an international market, this means that they will encounter legislation that is equivalent to Norwegian legislation in an increasing number of other countries. This will help to give the private sector more equal conditions of competition.

However, the Norwegian authorities are aware that not all countries enforce an anti-corruption standard that is in line with international conventions, and it may take some time before they do. For the foreseeable future, the private sector should therefore be prepared for challenging situations in countries where corruption is widespread.

The authorities and the private sector have a shared responsibility to combat corruption. They also have a shared responsibility to promote the greatest possible degree of transparency with regard to capital flows, particularly in connection with operations in developing countries.

Most major Norwegian companies with operations abroad have developed their own internal guidelines and routines for combating corruption. The challenge is to implement and follow up these guidelines in practice.

The Government

expects companies to respect fundamental human rights, including those of children, women and indigenous peoples, in all their operations, as set out in international conventions;

expects companies to base their operations on the ILO core conventions regarding the right to organise and the abolition of forced labour, child labour and discrimination;

expects companies to maintain HSE standards that safeguard employees’ safety and health;

calls on the social partners to actively advocate global corporate agreements in order to safeguard employees’ rights;

expects companies operating in countries where universal rights such as the right to organise and the right to collective bargaining are not upheld to seek to establish other arrangements that enable employees’ views to be heard;

expects companies to take into account environmental considerations and promote sustainable development, for instance by developing and using environmentally sound technology;

expects companies to actively combat corruption by means of whistle-blowing or notification schemes, internal guidelines and information efforts;

expects companies to show the maximum possible degree of transparency in connection with financial flows.

Textbox 3.8 Anti-corruption provisions of the Penal Code

Section 276a. Corruption

Any person who

for himself or other persons requests or receives an improper advantage or accepts an offer thereof in connection with a position, office or assignment, or

gives or offers any person an improper advantage in connection with a position, office or assignment shall be liable to a penalty for corruption.

Position, office or assignment in the first paragraph also means a position, office or assignment in a foreign country.

The penalty for corruption shall be fines or imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years. Any person who aids and abets such an offence shall be liable to the same penalty.

Section 276b. Gross corruption

Gross corruption shall be punishable by imprisonment for a term not exceeding 10 years.

Any person who aids and abets such an offence shall be liable to the same penalty. In deciding whether the corruption is gross, importance shall be attached to, inter alia, whether the act has been committed by or in relation to a public official or any other person in breach of the special confidence placed in himby virtue of his position, office or assignment, whether it has resulted in a considerable economic advantage, whether there was any risk of considerable damage of an economic or other nature, or whether false accounting information has been recorded, or false accounting documents or false annual accounts have been prepared.

Section 276c. Trading in influence

Any person who

for himself or other persons requests or receives an improper advantage or accepts an offer thereof in return for influencing the conduct of any position, office or assignment, or

gives or offers any person an improper advantage in return for influencing the conduct of a position, office or assignment shall be liable to a penalty for trading in influence.

Position, office or assignment in the first paragraph also mean a position, office or assignment in a foreign country.

Trading in influence shall be punishable by fines or imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years. Any person who aids and abets such an offence shall be liable to the same penalty.

3.3 The scope of corporate responsibility

Companies should be aware of issues within their «sphere of influence» that affect their operations or are a result of them. In Norway there is a widespread view that companies have a responsibility towards their employees, and that they are part of, and have a responsibility towards, the society in which they operate. Companies’ activities have financial, environmental and social consequences that it is only reasonable that they take responsibility for. However, the extent of this responsibility is not always clear.

According to the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative on business and human rights, the starting point for corporate responsibility must be to consider whether the company has shown «due diligence». There are a number of different steps a company can take in order to operationalise the concept of due diligence. The concept can help companies gain an awareness of, prevent and address the negative consequences of their operations. In his April 2008 report, the Special Representative states that a human rights due diligence process should include four areas:

Textbox 3.9 Combating corruption

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs provides a business anti-corruption portal, with tools for companies’ anti-corruption efforts. The brochure Say no to corruption – it pays! has been circulated to Norwegian companies by way of the embassies and other government bodies. The brochure contains information on the Penal Code and the following checklist for combating corruption:

Undertake thorough studies of the risk of corruption in the relevant markets.

Ensure that all employees are familiar with the Norwegian and relevant foreign legal provisions on corruption.

Introduce ethical guidelines, regular internal audits and routines for detecting irregularities.

Consider establishing a contact point, preferably outside the company, that employees can turn to if they have any suspicions of corruption.

Ensure that employees, intermediaries and agents are involved on a regular basis in measures to reduce the risk of corruption.

Be particularly aware of roles in which employees could come under strong pressure to offer or accept bribes. Job rotation and other measures to reduce the risk of corruption should be considered.

Check the references of employees, agents and partners who represent the company and insofar as possible keep a close eye on their activities.

Require that employees, intermediaries and agents agree to comply with the company’s rules for combating corruption.

Maintain a high ethical standard and avoid circumstances that could call impartiality into question.

When faced with a difficult situation, focus on mutual interest in working together in an open, lawful manner. Suspicions of corruption can have extremely serious consequences.

Seek the advice of experts if necessary.

Policies: companies should adopt a human rights policy;

Impact assessments:companies should carry out impact assessments regarding the implications of their activities;

Integration: human rights policies should be integrated throughout a company;

Tracking performance: companies should have a system for monitoring and auditing in order to track their human rights performance on an ongoing basis.

Processes of this kind also have relevance for the other aspects of the CSR concept. Assessments of due diligence can often be linked to the notions «sphere of influence» and «complicity». It is therefore pertinent to take a closer look at these concepts.

Companies’ sphere of influence

As far as the scope of companies’ responsibility is concerned, it is natural to start with matters companies are able to influence. Responsibility can be most clearly attributed to companies for matters over which they have a decisive influence or control. They can also incur responsibility when they outsource functions and assignments to others, since this can be viewed as part of the company’s own operations.

Companies are responsible for ensuring that employees are provided with conditions that are at least in line with international minimum standards. Companies are expected to assess the risks relating to forced labour, child labour and workplace discrimination, and to take the necessary precautions to minimise such risks. Freedom of association, freedom of expression and freedom of religion and belief are also rights that companies should respect.

Companies also have a direct influence over their own contractual relations, and over the environmental consequences of their activities. Norwegian companies can contribute to raising standards by facilitating good corporate culture, by having good routines for health, safety and environment (HSE), and by transferring knowledge and technology to their own operations abroad and to their subcontractors.

Usually a company engaged in international operations will also have significant influence over – if not actual control of – matters relating to the company’s surroundings, for instance the local community and contractual parties. By setting contractual terms and making sure that all the actors in the value chain provide decent working conditions for their employees and meet key environmental standards, companies take responsibility for their surroundings. Companies may also have a responsibility towards other groups. An example of this is if a company buys security services from local security forces in its area of operation.

The further removed something is from a company’s core activities, the harder it is to argue that the company can exert a decisive influence over it. Companies and their representatives may wish, or consider it in their interests, to take a clear stance against serious human rights abuses. However, some host countries may react negatively to a company getting involved in human rights issues within their jurisdiction, particularly if these issues are political in nature. In any case, a company should keep abreast of key developments in the country in which it is operating, including developments in the human rights situation.

Some companies wish to contribute to humanitarian efforts outside their own sphere of influence. This involvement may be linked to economic, social and cultural rights, for instance through aid projects in the areas of health, infrastructure, education or sport. There are also examples of companies supporting the promotion of civil and political rights.

Complicity

Companies must make sure that they are not complicit in unethical practices. The Ethical Guidelines for the Norwegian Government Pension Fund – Global also state that the Fund should not make investments which constitute an unacceptable risk that the Fund may contribute to serious or systematic violations of human rights. What is meant by this is explained in Official Norwegian Report NOU 2003:22, Management for the future: Proposed ethical guidelines for the Government Petroleum Fund, inter alia drawing on the scope of complicity as set out in Norwegian law:

«In order for an investor to be complicit in an action, he/she must be able to foresee it. Some form of systematic or causal relationship must exist between the company’s activities and the actions to which the investor does not wish to contribute. Investment in a company cannot be considered to entail complicity in actions that were impossible to anticipate or be aware of or circumstances over which the company in question could not have any significant degree of control.»

There is no clear internationally agreed definition of complicity, but the concept is being emphasised to an increasing extent by investors and NGOs. The UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative on business and human rights has examined the issue of complicity more closely in relation to human rights. In his view, the concept refers to «indirect involvement by companies in human rights abuses – where the actual harm is committed by another party, including governments and non-State actors». Moreover, it has both legal and non-legal meanings.

The legal meaning of complicity is particularly relevant in connection with international crimes. Here, providing encouragement or practical assistance that has a substantial effect on the commission of the crime may constitute complicity. In September 2008, the International Commission of Jurists Expert Legal Panel on Corporate Complicity in International Crimes published an extensive report on this topic.

The above-mentioned Official Norwegian Report on proposed ethical guidelines for the Government Petroleum Fund gives examples of various scenarios relevant to the concept of complicity:

«Particular problems arise in connection with companies that have activities in states where severe human rights violations occur. Such violations can also occur in connection with the companies’ activities, for example by using security forces that commit abuses to protect the company’s property and installations, deportation of people and environmental degradation to facilitate the company’s projects or arrests and persecution of workers who are seeking to promote trade union rights. Complicity on the part of the company can be invoked only if direct action is taken to protect the company’s property or investment, and the company has not taken reasonable measures to prevent the abuse.»

If companies cooperate closely with the authorities of countries with weak governance, they must demonstrate special vigilance and deal constructively with difficult dilemmas. This is particularly the case if companies can be suspected of benefiting from the authorities’ conduct, or if the cooperation can help to legitimise the authorities.

Certain countries, including the US, have defined complicity in their domestic legislation, and have given the courts broad jurisdiction to assess alleged human rights violations in connection with companies’ operations abroad.

Through due diligence, for instance by carrying out risk assessments, companies can ensure that they are not complicit in human rights violations or other negative impacts of their own operations. Risk assessment should be used both for a company’s own activities and for those of its business partners. There are a number of tools – both general and sector-specific – that companies can use in this process. One such tool is the Human Rights Compliance Assessment (HRCA), developed by the Danish Institute for Human Rights.

3.4 Social responsibility in the supply chain

Social responsibility in the supply chain is a rapidly developing field, which is attracting growing attention and becoming increasingly important. Outsourcing and major changes in the international division of labour mean that more and more factor inputs in the public and private sectors, as well as finished goods on the market, come from countries where the authorities do not provide adequate control of working conditions and protection of workers’ rights. There is growing concern that goods and services imported to Norway should be produced under satisfactory working conditions, and that factors such as children’s and women’s rights and environmental considerations should also be taken into account.

Today, all companies with activities in or that use suppliers in countries where the legislation does not meet internationally accepted standards, or is not properly enforced, have to take the whole supply chain into consideration. Companies may need to cooperate through trade associations or with their competitors in order to prevent violations of human rights or labour rights in the supply chain and ensure that operations are environmentally sound.

3.4.1 How far does the responsibility extend?

Socially responsible companies accept responsibility for ensuring, to the extent possible, that all stages of the supply chain meet their standards. At present, it is not realistic to expect imported goods or semi-finished products from all countries to have been produced without any risk of direct or indirect involvement in violations of internationally recognised norms and rules. In practice, there are often both practical and financial limitations concerning how far down the value chain it is possible for an individual company or procurement organisation to carry out quality controls of its suppliers. It is seldom possible for a company to control all processes, from the extraction of raw materials right up to waste management. Furthermore, it can be difficult to know where to draw the line.

Figure 3.6 Textile production in China. The use of face masks is a simple but essential protective measure for textile workers.

Source Ethical Trading Initiative Norway (ETI-Norway).

It seems most reasonable to set as a minimum standard that a company’s responsibility covers the sphere it can influence directly as a purchaser and seller, through contracts or in other ways. If suppliers have to meet requirements relating to working conditions and environmental issues, and ensure that subcontractors meet similar requirements, they can be held accountable.

The challenges that arise vary between companies and products. Rather than seeking to delimit its responsibilities, it is more important for a company to look into the risks of violations of human and workers’ rights or adverse impacts on the environment at different stages of production processes, including the production of factor inputs. Thus, the introduction of ethical guidelines in the supply chain can be regarded as a risk management tool.

So far, both practical experience and research point in the same direction, indicating that introducing requirements for social responsibility in the supply chain can create opportunities, both for business development and for improving financial performance. Key factors in this context are long-term systematic improvement and competence-building in the supply chain. Companies can gain a competitive advantage by adjusting quickly to forthcoming regulations and long-term market developments, and not least by meeting market expectations.

Textbox 3.10 Cooperation between Stormberg and its suppliers

Stormberg is a sports and textiles wholesaler. The company is seeking to take workers’ rights and environmental considerations into account in its operations in Norway and abroad.

Outdoor clothing is designed and developed in Norway, but manufactured at a number of factories in China. According to the company’s ethical guidelines, all suppliers must provide well-regulated pay and working conditions and respect the right to organise and the right to enter into collective bargaining agreements. A Chinese version of the guidelines is displayed in the factories.

Stormberg carries out spot checks of the factories, sometimes unannounced. Stormberg has drawn up a profile for each factory as a basis for inspection and control, which identifies factors to which special attention should be paid. In addition, inspectors are provided with a list of points to check, and also conduct interviews with workers at the factories.

So far, the public debate on supply chains has focused primarily on the importance of setting minimum requirements for suppliers. However, many consumers expect more than this, and consider ethical standards to be important when making purchases. In order for consumers to be able to make informed choices, it is important to ensure the greatest possible degree of transparency with regard to production abroad. In the Government’s view, it is important that consumers and consumer organisations are given access to information, so that they can adapt their consumption to their personal convictions.

3.4.2 Ethical requirements in the supply chain

Taking responsibility for the supply chain means that companies do not just set requirements for their suppliers, but also work with them to help them meet their obligations. This requires concrete, sustained efforts to improve the situation, and companies must be prepared to follow up their suppliers over the long term. No company can work equally closely with all its suppliers at all times. But everyone can make a start.

A company can observe and monitor how its suppliers comply with their obligations by cooperating closely with them, and by visiting their premises. This will also increase suppliers’ awareness of their obligations and further the transfer of knowledge and experience. Norwegian companies can for example contribute expertise on HSE, environmental management and dialogue between the social partners, as well as demonstrating how improved working conditions can enhance productivity and quality.

A natural first step is to develop a code of conduct that as a minimum is in line with international conventions and standards. There are also sector-specific standards that correspond to codes of conduct, for the textile industry, for instance. Codes of conduct can be used to convey what is expected of suppliers as regards both ethical and environmental standards.

Recent research 1 and established good practice indicate that if ethical guidelines are to function as intended and meet the expectations of employees and other stakeholders, the following are important elements:

that codes of conduct are drawn up in line with international workers’ and human rights and environmental standards, so that the requirements suppliers must meet are as standardised as possible, even when they are made by different actors; 2

that the requirements suppliers must meet are primarily in line with applicable national legislation, but alternatively in line with internationally recognised standards if there is no relevant national legislation or it is inadequate;

that requirements and the monitoring of compliance with these are combined with competence-building and exchange of experience;

that wherever possible, control, monitoring and competence-building are carried out by actors with a firm basis in the local community and good cultural understanding;

that codes of conduct are implemented on the basis of an integrated approach to CSR and with the support of the management and the board.

Textbox 3.11 Ethical Trading Initiative Norway (ETI-Norway)

ETI-Norway was founded in 2000 by Norwegian Church Aid, the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO), the Federation of Norwegian Commercial and Service Enterprises (HSH) and Coop Norway, to promote ethical trade practices in the supply chain. As of November 2008, ETI-Norway had around 95 members. It has two main objectives:

Strengthening support for ethical trade issues; and

Supporting members in developing ethical trade practices.

ETI-Norway spreads information on the importance of improved labour and environmental standards globally. It also makes use of knowledge-sharing and tools to strengthen its members’ ethical trade practices.

Members commit to working towards improvements in labour and environmental standards throughout their supply chains. Their performance is measured through annual reports. Members’ efforts should be based on:

Information concerning labour and environmental standards in producer countries;

Specific tools and methods;

Risk assessment and risk management;

Training initiatives and guidance;

Cooperation between companies, authorities, special interest organisations, trade unions, research institutions and NGOs, both locally and internationally; and

Competence-building in international networks.

The Ethical Trading Initiative Norway (ETI-Norway) is a resource centre that seeks to strengthen support for ethical trade practices throughout the supply chain. ETI-Norway provides its public- and private-sector members with information, methods and tools they can use when setting requirements for decent working conditions and the inclusion of environmental considerations throughout the supply chain.

To ensure that suppliers comply with labour standards, companies can encourage them to obtain certification. SA 8000 is the most widely recognised generic certification standard. It is primarily intended for producers, and SA 8000 certification shows that a facility respects workers’ rights. Using recognised standards saves time and resources, for both customers and producers. There are also environmental management systems that use third-party certification, such as ISO 14001, the voluntary EU Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS), and the Norwegian Eco-Lighthouse Programme, see Chapter 6.4.

Product labelling is another way of showing that products are produced in accordance with social or environmental standards. Examples of such labels are the Nordic Swan, the EU Flower, the forthcoming EU Organic Logo, the FAIRTRADE Mark, environmental declarations (in line with ISO 14025), the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) label, and the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) eco-label.

Product labelling is a tool for consumers to obtain information about the ethical and environmental standards of products. Companies can also choose to provide this information in other ways. Regardless of how the information is provided, it is important to ensure that consumers are not misled by incorrect, imprecise or poorly documented claims. In February 2005, the Nordic Consumer Ombudsmen adopted a joint guideline on the use of ethical and environmental claims in marketing. The Norwegian Consumer Ombudsman adopted guidelines in this area in June 2003. These are based on the Marketing Act, and they require that all advertising must convey a clear and balanced message, that it must give a correct overall impression, that it must be based on fact, and that it must be possible to substantiate all claims. It will probably be possible to continue to use these guidelines after the new Marketing Act comes into force in spring 2009.

3.4.3 Greening supply chains

In recent years, environmental supply chain management has become an increasingly important part of companies’ environmental strategies, partly as a result of the growing attention end users and institutional investors are paying to environmental issues. While in the past companies’ environmental strategies were primarily based on the need to minimise risk, there has more recently been growing awareness that an active approach to environmental responsibility can be commercially profitable. Environmentally-friendly production methods often prove to be cheaper, and corporate governance is often better in companies that have introduced environmental management systems than in those that have not.

Product design, production and material use, and transport and logistics are key areas where companies can influence their environmental profile by making conscious choices. For most companies, working towards a greener supply chain is a matter of improving existing structures.

Through life cycle assessment, companies can obtain information and documentation on the overall environmental impact of products, during all phases of the life cycle, from production to use, re-use and waste management. By keeping a greenhouse gas inventory, or calculating its carbon footprint, a company raises awareness of and documents its impact on the climate.

A company needs to make conscious choices at various stages of its operations and procurement processes in order to take environmental concerns properly into account. Examples of such stages include:

Choosing the business concept;

Choosing an environmental profile;

Determining procurement specifications;

Drawing up invitations to tender;

Entering into contracts;

Following up deliveries;

Choosing between partnership and ad hoc procurement.

Systematic review and analysis of supply chains, any internal, external and country-specific challenges, and which areas should be given priority, are needed as a basis for developing an environmental strategy and a green procurement strategy. One strategic choice a company must make is whether to make this an internal process or to seek partnerships with other companies. The overall strategy must define areas of responsibility and the division of roles and tasks within the company, and specify how environmental concerns are to be included in the company’s procurement criteria and supply chain management. The company must also decide how to organise communication with its suppliers, and whether support functions and training programmes are needed for employees of the company itself and its suppliers. Incentive schemes and monitoring and evaluation systems should also be developed.

The Government

considers that to the extent possible, socially responsible companies should ensure that all stages of the supply chain meet the company’s standards;

calls on Norwegian companies to set social and environmental requirements for their suppliers and business partners;

calls on Norwegian companies to develop systems for ensuring that suppliers comply with internationally recognised codes of conduct;

calls on companies to play a part in capacity building and competence building in the supply chain.

3.5 Investment and investment management

Certain areas of the financial sector’s activities, including advisory services, marketing, and the sale of advanced structured products have recently come under increasing critical scrutiny, particularly in the light of the global financial crisis. The criticism has concerned the fact that risks have been downplayed and the real rates of return exaggerated. The Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway has on a number of occasions pointed out that companies have failed to observe good business practice in their financial advisory services and their marketing of such products and services.

Financial institutions and investment firms give advice and provide services that can have major consequences for consumers. In their contact with consumers, these institutions and firms are always the professional party. This is why a licence is required for the sale of insurance products, loans, and advice on financial instruments. Licensees have a particular duty of care towards consumers when selling financial instruments and loan and insurance products.

However, in recent years, leading financial institutions have started to focus on their social responsibility. This applies particularly to investors and fund managers, who are giving increasing weight to ethical standards in their investment and sales decisions. Some banks and insurance companies have also become more concerned with ensuring that their loan and insurance customers meet satisfactory social responsibility standards.

3.5.1 Socially responsible investment

One reason why actors in the capital market are focusing more on CSR is that professional investors have become more aware of the importance of environmental and social factors for the value of their own investments. In addition, investors are also being held accountable for matters other than financial returns. Investors are increasingly expected to include ethical considerations when investing, both their own and their customers’ funds. A number of Norwegian financial institutions have therefore introduced CSR criteria as a basis for their investments.

Investors and fund managers have used the term socially responsible investment (SRI) to describe investments where financial returns are an important aim, but where ethical and environmental requirements are also taken into account. Responsible investment (RI) is a term that is increasingly used to describe the inclusion of environmental considerations, social conditions and good corporate governance in fund management. These are factors that can have a long-term financial effect.

SRI is not new for investors. When the Methodist Church in the US started investing in the stock market in the early 1900s, it avoided shares associated with alcohol or gambling. In Norway, interest in socially responsible investment arose at the end of the 1980s. Gradually, socially responsible investment developed from a small niche to an area of interest to ordinary investors. Other parts of the financial sector have started taking initiatives to meet challenges and utilise opportunities relating to CSR in connection with their loan and investment activities.

Considerable technical expertise has been built up in this area, and several companies have developed their own analysis tools. Certain companies qualify for inclusion on international sustainability indexes, such as the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index and the FTSE4Good Index. These measure the performance of major companies that are seeking to meet CSR criteria.

Financial institutions can take different approaches when setting requirements for non-financial factors in connection with investments. Three methods are widely used, either individually or in combination:

Negative screening enables financial institutions to avoid investing in the worst companies using criteria that define where they do not wish to invest. These criteria are generally connected to what is produced, for example landmines, cluster munitions, nuclear weapons or tobacco. Criteria can also be drawn up for the way companies manage their operations, for example whether they are responsible for serious violations of human rights, or involved in corruption or major environmental damage. This method is often used by funds that set minimum ethical standards, such as the Government Pension Fund – Global. Some investment managers publish the names of the companies they pull out of, and believe that this increases pressure on companies to improve their performance in this area.

Textbox 3.12 The UN Principles for Responsible Investment

We will incorporate environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) issues into investment analysis and decision-making processes.

We will be active owners and incorporate ESG issues into our ownership policies and practices.

We will seek appropriate disclosure on ESG issues by the entities in which we invest.

We will promote acceptance and implementation of the Principles within the investment industry.

We will work together to enhance our effectiveness in implementing the Principles.

We will each report on our activities and progress towards implementing the Principles.

Another approach to socially responsible investment is positive screening, which entails comparing companies to identify which are the best. Companies within the same sector are rated according to their CSR performance. Factors such as environmental management systems, measures to fight corruption, principles of corporate governance, conditions for the employees, and guidelines to safeguard human and workers’ rights are used as criteria. The rating enables an investor to select the best companies in each sector. These companies qualify for inclusion in «best in class» funds – funds that set extremely high CSR requirements for their operations. The same analyses and criteria can also be used to exclude the poorest companies in each sector.

The third commonly used method is active ownership. Investors can seek to exert a positive influence on companies that they are critical towards by engaging them in dialogue or taking active part in the company’s general meetings. There are several examples of international pressure being used in this way to influence companies to make changes to their operations. Some people maintain that it is more effective to increase investments in companies that are seen in a critical light, in order to exert a positive influence on them through active ownership.

In addition, a number of investment managers provide specialised funds that focus on particular sectors, such as renewable energy and environmental technology. Investing in these funds entails a higher risk than investing in broad index funds. However, they provide investors who wish to invest in these sectors an opportunity to spread their investments in a cost-effective manner.

The extent to which companies and organisations outside the financial sector use CSR as a criterion for investment management is unclear. However, it is expected that these actors too will direct increasing attention to social responsibility.

A number of financial institutions have adopted the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI). Following an initiative by the UN Secretary General, six principles for responsible investment were drawn up in a process involving representatives of the world’s largest institutional investors in cooperation with representatives of the financial sector, the authorities, civil society and research institutions during the period 2005–2006. The principles reflect the core values of large investors, whose investment horizon is generally long, and whose portfolios are often highly diversified. In Norway, the principles have been adopted by DnB NOR, KLP, Nordea, Norges Bank on behalf of the Government Pension Fund – Global, and Storebrand.

CSR is also becoming increasingly important in the banking sector. Several institutions have developed their own CSR analysis tools for their lending activities. These are used in connection with risk management. The Equator Principles constitute the international standard for responsible lending, see Box 3.13. Many companies also use their own guidelines for lending and for portfolio investments.

Textbox 3.13 Equator Principles

The Equator Principles are a set of voluntary guidelines relating to project financing, which are largely based on policies and guidelines from the private sector investment arm of the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation (IFC). Ten leading banks, with Citigroup at the helm, adopted the Principles in 2003.

Institutions that use the Equator Principles have committed themselves to only financing projects that are to be implemented in a socially and environmentally responsible way. By establishing these principles, the banks have agreed not to compete on the basis of environmental and social factors.

Under the principles, the banks have committed themselves to requiring environmental impact assessments, public consultation, and general project management that is in accordance with various minimum standards regarding environment, human rights and working conditions. As of December 2008, around 60 financial institutions were employing the principles in their financing activities. In Norway, the principles have been adopted by DnB Nor and Nordea.

The 12 largest institutional investors in Norway have launched a collaborative project called Sustainable Value Creation (Bærekraftig verdiskaping). They have carried out a survey of the companies listed on the Oslo Børs (Oslo stock exchange) Benchmark Index, the results of which were published in December 2008. The aim of this initiative is to encourage Norwegian listed companies to focus on sustainable development and long-term value creation. Altogether, the investors supporting the project represent assets amounting to NOK 2 700 billion, NOK 1 000 billion of which is invested directly in the Norwegian market.

The Government

calls on institutions in the private financial sector to give more weight to social responsibility as an important element in their overall activities;

will encourage all parts of the financial sector to increase transparency with regard to investments.

3.6 Responsibilities and opportunities

There are considerable opportunities for internationally oriented companies to increase their competitive edge through socially responsible practices. Upholding good values and integrating CSR into business management enables companies to identify and utilise new market opportunities.

Systematic CSR work has primarily been undertaken in large companies with extensive international involvement. Most of Norway’s private sector is made up of small and medium-sized enterprises. Smaller companies tend not to have the resources or expertise to work as systematically and thoroughly with CSR as larger companies. Advisory services targeting smaller companies are discussed in Chapter 9.

The Government believes that all companies have responsibilities that extend beyond value creation in purely economic terms. Through socially responsible practices, it is possible for all companies to promote social and environmental values while at the same time strengthening their long-term competitiveness.

Footnotes

The ETI code of labour practice: Do workers really benefit? Institute of Development Studies 2006.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the core ILO conventions and other ILO conventions and documents dealing with matters such as HSE, working hours and the right to a living wage.