6 International frameworks for corporate social responsibility

Figure 6.1

With globalisation, business is becomingly increasingly internationally oriented, making it more necessary than ever for enterprises to operate in a responsible manner. This forms the backdrop for international efforts in the OECD, the UN and other organisations to establish a normative and more binding framework for companies. This framework consists partly of international conventions that governments are obliged to comply with, and partly of voluntary instruments for responsible business conduct.

The Government is engaged in efforts to strengthen international guidelines and to develop regional and global standards that will as far as possible ensure that businesses have equal framework conditions. The Government’s aim is that Norway should be a leading nation in such efforts, both by taking action on its own initiative and by supporting the actions of others. The Government is also supporting efforts to monitor compliance with guidelines and standards.

The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises contain detailed recommendations for enterprises operating in or from OECD countries, and a special mechanism for promoting and following up the Guidelines in the form of National Contact Points (NCPs). The UN Global Compact is a global initiative that sets out principles for businesses and has broad participation from developing countries. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) promotes transparency and provides guidance for reporting on the economic, social and environmental impacts of companies and organisations.

Such widely recognised international standards and instruments are useful for guiding and clarifying the private sector’s engagement in the field. Businesses that follow the same international guidelines are able to exchange ideas and experience, making it easier to measure and compare results and meet the expectations of governments, employees and society. When enterprises base their business activities on the same international guidelines, the competitive environment becomes more equal, resulting in a more level playing field.

6.1 The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises

The OECD established a set of guidelines for multinational enterprises as early as 1976, and was thus a pioneer in the field of CSR. The OECD Guidelines are the only multilaterally recognised framework that governments are committed to promoting. They consist of a set of recommendations by governments to multinational enterprises, and include a comprehensive framework of voluntary principles and standards for responsible business conduct consistent with applicable laws.

The Guidelines are part of the OECD Declaration on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises of 1976, the purpose of which is to improve the investment climate and encourage the positive contribution multinational enterprises can make to economic and social progress. The Guidelines are based on the principle that multinational enterprises are in a better position to promote sustainable development when trade and investment are conducted in a context of open, competitive and appropriately regulated markets. The Guidelines were most recently updated in 2000.

The Guidelines contain recommendations that reflect the ILO core conventions on forced labour and child labour. Multinational enterprises are encouraged to raise the level of their environmental performance through improved internal environmental management and better contingency planning for environmental impacts. The Guidelines contain provisions on human rights, combating corruption and consumer protection. Business partners, including suppliers and subcontractors, are encouraged to base their conduct on the Guidelines. Small and medium-sized enterprises are also encouraged to observe the Guidelines.

Textbox 6.1 General policies (Chapter II of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises)

Enterprises should take fully into account established policies in the countries in which they operate, and consider the views of other stakeholders. In this regard, enterprises should:

Contribute to economic, social and environmental progress with a view to achieving sustainable development.

Respect the human rights of those affected by their activities consistent with the host government’s international obligations and commitments.

Encourage local capacity building through close cooperation with the local community, including business interests, as well as developing the enterprise’s activities in domestic and foreign markets, consistent with the need for sound commercial practice.

Encourage human capital formation, in particular by creating employment opportunities and facilitating training opportunities for employees.

Refrain from seeking or accepting exemptions not contemplated in the statutory or regulatory framework related to environmental, health, safety, labour, taxation, financial incentives, or other issues.

Support and uphold good corporate governance principles and develop and apply good corporate governance practices.

Develop and apply effective self-regulatory practices and management systems that foster a relationship of confidence and mutual trust between enterprises and the societies in which they operate.

Promote employee awareness of, and compliance with, company policies through appropriate dissemination of these policies, including through training programmes.

Refrain from discriminatory or disciplinary action against employees who make bona fide reports to management or, as appropriate, to the competent public authorities, on practices that contravene the law, the Guidelines or the enterprise’s policies.

Encourage, where practicable, business partners, including suppliers and subcontractors, to apply principles of corporate conduct compatible with the Guidelines.

Abstain from any improper involvement in local political activities.

The OECD Guidelines are voluntary, and the authorities cannot impose sanctions for violations. On the other hand, the member countries are obliged to establish National Contact Points (NCPs) as central bodies for effective implementation of the Guidelines.

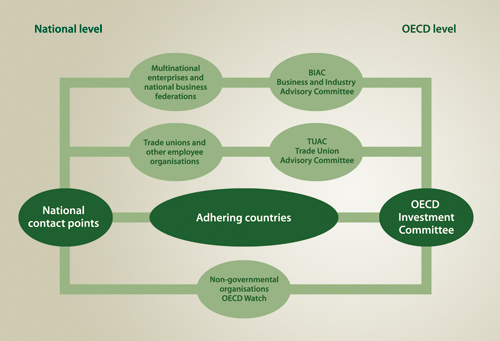

One of the strengths of the Guidelines is that they are supported by business and labour organisations, both of which work actively to disseminate information about them. The private sector’s and the trade unions’ OECD committees, the Business and Industry Advisory Committee (BIAC) and the Trade Union Advisory Committee (TUAC), participate in following up the Guidelines, as does the OECD Investment Committee. OECD Watch, an international network consisting of more than 65 voluntary organisations, including the Norwegian Forum for Environment and Development (ForUM), monitors the work and the development of the Guidelines.

In addition to the OECD’s 30 member countries, 11 observer countries have endorsed the Guidelines. 1 In all, this covers the countries in which most of the multinational enterprises have their headquarters and a large proportion of their operations. Roughly 85 % of foreign investment flows are to countries that endorse the Guidelines.

6.1.1 National Contact Points

The National Contact Points (NCPs) have a central role in following up the Guidelines. They serve as a forum for dealing with complaints for violation of the Guidelines brought against companies that operate in or from countries that have endorsed the Guidelines. Although the NCPs are not legal bodies, they may assess whether or not companies have violated the Guidelines. The aim is to resolve issues or conflicts concerning the Guidelines through discussion with the parties involved. The NCPs can thus help to make companies more aware of their responsibility and increase the legitimacy of the Guidelines.

NCPs handle inquiries, disseminate information about the Guidelines and issue annual reports on their activities to the OECD Investment Committee. Annual meetings are also held at which the NCPs can share their experience of promoting the Guidelines.

The core criteria that are to guide the NCPs work are visibility, accessibility, transparency and accountability. The authorities are to play an active role in disseminating information about the NCPs and promoting the Guidelines. Transparency helps to make the NCP more accountable and increases the general public’s trust. The outcome of the NCPs evaluations should therefore be transparent unless considerations of effective implementation of the Guidelines indicate the need for confidentiality.

Figure 6.2 Institutions involved in following up the OECD Guidelines

Several factors are decisive when an NCP handles complaints (known as «specific instances») regarding companies’ compliance with the Guidelines. Among other things, it must consider how the complaint relates to national legislation, how corresponding complaints have been dealt with previously and whether the processing of the complaint contributes to implementation of the Guidelines. If a complaint requires further consideration, the NCP will endeavour to resolve it through discussions with the parties. This can include consultation with other NCPs or the OECD Investment Committee. Normally, a complaint concludes with a statement from the NCP. In such cases, the parties have an opportunity to pursue the matter further through the BIAC and the TUAC.

The OECD publishes complaints submitted to NCPs and issues statements in such cases. Since the Guidelines were revised in 2000, the NCPs have received 181 complaints, 131 of which have been considered. 2

6.1.2 The Norwegian National Contact Point

Norway’s NCP is a cooperative body composed of representatives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Trade and Industry, the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO) and the Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise (NHO). So far, three complaints have been considered by the NCP. The cases involved Gard’s contracts with Indonesian and Filipino seafarers (2002), Aker Kværner’s activity at Guantanamo Bay (2005) and Nordea’s financing of a paper pulp factory in Uruguay (2007).

Textbox 6.2 Complaints considered by the Norwegian NCP

The Gard complaint

The international Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) claimed that the Norwegian insurance company Gard was in breach of the OECD Guidelines. The reason was that seafarers from the Philippines and Indonesia had to sign a standard contract relieving the insurance company of all liability in the event of an injury or accident over and above what was stipulated in the contract.

The NCP took steps to obtain information in the specific instance, among other things through the Norwegian embassy. It turned out that national workers’ and employers’ organisations in the Philippines had signed an agreement on the matter. In a corresponding case, the Philippine Supreme Court had ruled that such agreements are not unlawful.

The NCP concluded that Gard had not violated the OECD Guidelines since the company was within the bounds of normal practice in the country where the employment relationship took place.

The Aker Kværner complaint

The Forum for Environment and Development (ForUM) claimed that, through its wholly owned US subsidiary Kværner Process Services Inc. (KPSI), Aker Kværner was in breach of the provision of the OECD Guidelines regarding respect for human rights (Chapter II, item 2) in that it provided assistance to the prison at Guantanamo Bay. The prison was established to house prisoners suspected of terrorism, and it was criticised because the prisoners were denied due process protection.

The specific instance concerned the question of whether Aker Kværner had aided and abetted, or profited from, violations of human rights. Ethical evaluations of such issues are based on the human rights provision of the OECD Guidelines.

Aker Kværner/KPSI was primarily involved in the running of the base, but it also contributed to maintenance and operational and supply functions that are common to the prison and the base. The NCP was of the view that the company’s activities must, at least in part, be deemed to affect the inmates of the prison. The running of the prison is dependent on the maintenance of infrastructure of the type involved in this complaint.

The NCP emphasised that Norwegian companies should continuously evaluate their operations in relation to human rights. The situation at Guantanamo called for particular vigilance. The NCP also urged the company to adopt ethical guidelines and to apply them in all countries in which Aker Kværner operates.

The Nordea complaint

The main issue in the Nordea complaint was whether banks and finance institutions can be held accountable for the activities of companies to which they lend money. The specific instance concerned whether Nordea has an independent responsibility as part-financer and provider of financial services to the Finnish company Botnia in connection with the establishment of a paper pulp factory in Uruguay.

In their processing of the complaint, the Norwegian and Swedish NCPs held several meetings with the parties and obtained factual information from embassies, various ministries and the World Bank. The Swedish and Norwegian NCPs concluded that there were no grounds for the allegations made against Nordea concerning breach of the OECD Guidelines. The NCP used the specific instance to urge Nordea and other companies in the financial sector to be as open as possible with information.

The procedures of the Norwegian NCP worked well in all three of the complaints considered by it. The NCPs composition reflects the Norwegian tripartite tradition. However, neither the OECD Guidelines nor the NCP are well enough known. The survey conducted for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2008, cf. Chapter 1, showed that only a small minority of Norwegian medium-sized and large enterprises are aware of the Guidelines.

Norwegian companies have expressed a need for clarification of what is required to comply with the Guidelines and recommend that the Guidelines should be made more user-friendly. Some have noted that the NCPs methods and procedures are unclear.

The Norwegian authorities will work to make the contents of the Guidelines and the NCPs methods and procedures better known. Instructions will be drawn up as well as web-based information about the Guidelines.

Textbox 6.3 OECD Watch Model National Contact Point

In 2008, OECD Watch published a handbook, Model National Contact Point, which, among other things, includes the following recommendations for the NCPs:

The necessary training and adequate resources must be provided if the NCPs are to function as intended.

The NCPs should adopt a strategy for promoting the guidelines, hold seminars and annual consultations with various stakeholders and make active use of embassies and trade missions to promote the guidelines.

Complaints should be dealt with within a reasonable time frame and preferably within 12 months.

Procedures should be transparent and the NCP should keep the parties informed and treat them equitably throughout the process.

6.1.3 Experiences and potential for improvement

There is great variation within the OECD with respect to the composition and organisation of NCPs. In some member countries, the NCP includes representatives of both the authorities and NGOs, while in others only the authorities are represented. The Netherlands recently established a new, independent national contact point composed solely of representatives from the private sector, academia and civil society. Norway, Sweden and Denmark have based their NCPs on a tripartite structure patterned on the tripartite cooperation that has a long-standing status in the Nordic countries. In Sweden, civil society is also represented in the NCP.

Several member countries have pointed out the need for a better overview of the complaints submitted to the NCPs. For example, there is no satisfactory system at present that registers whether a subsidiary operating in a different country than the parent company has been brought before the NCP in that country. A parent company in Norway may be completely unaware that that its subsidiary is involved in a complaint being dealt with by another country’s NCP, unless the local NCP has informed the NCP in Norway about the case. Norway will actively support OECD initiatives to ensure an improved information flow between NCPs in such cases.

One challenge facing the OECD is promoting the principles in countries that have not endorsed the Guidelines. Several member countries consider this important and have taken the initiative to translate the Guidelines into other languages.

If the Guidelines are to remain relevant and keep pace with global developments, they must be regularly updated. It is more than eight years since the Guidelines were last revised, and important developments have taken place in the field since then. In other words, the time seems ripe for updating the OECD Guidelines. Today, the Guidelines have a broad scope, but in certain areas they are imprecise. As regards human rights, for instance, it may be necessary to specify considerations regarding local communities and indigenous peoples’ rights more clearly. In the light of recent developments, it may also be necessary to update the Guidelines as regards the environment and climate. This can be done in the form of new supplements to the text. Norway has worked actively for the Guidelines to be updated in these areas. With the support of other member countries, the matter has been included in the OECD Investment Committee’s work programme for 2009–2010.

The Government

will strengthen the NCP’s procedures and make its functioning more transparent;

considers that the tripartite nature of the NCP is of great importance to its work and authority;

will provide more resources for the Norwegian NCP and encourage the use of independent advisers and experts;

will work to increase knowledge and guidance about the Guidelines, among other things through the NCP and relevant public instruments;

participates actively in the work of the OECD on revising the Guidelines in areas such as human rights and the environment/climate;

will work to increase the number of countries that endorse the OECD Guidelines.

6.2 The UN Global Compact

The Global Compact is the UN’s initiative for cooperation with the private sector on sustainable development. The initiative was taken by then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan in 1999 in an endeavour to involve the private sector more directly in development efforts. When it was launched at the meeting of the World Economic Forum, Kofi Annan gave the following reasons for the initiative:

«I propose that you, the business leaders gathered in Davos, and we, the United Nations, initiate a global compact of shared values and principles, which will give a human face to the global market.»

The idea behind the Global Compact is for companies to endorse 10 fundamental principles. They entail companies supporting and respecting international human rights and central labour rights, promoting environmental responsibility and combating corruption. The principles are based on the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the ILO’s core conventions, the Rio Principles on Environment and Development and the UN Convention against Corruption

Businesses make the 10 principles an integral part of their business strategies and day-to-day operations.

With its basis in the UN and its broad scope, the Global Compact is the most universal framework for social responsibility. The principles constitute an international «soft law» standard for businesses’ work in the field of CSR. The initiative should have the potential to gain widespread support in Norway and the rest of the world, not least in developing countries.

Today, the Global Compact is the world’s largest voluntary initiative for CSR. Roughly 4 000 businesses from more than 120 countries have endorsed it. Employers’ and workers’ associations and NGOs come in addition. The total number of members at the end of 2008 was approximately 5 200. Twenty-six Norwegian companies and organisations have joined the Global Compact.

Textbox 6.4 The UN Global Compact – 10 principles

Human rights

Businesses should support and respect the protection of internationally proclaimed human rights, and

Make sure that they are not complicit in human rights abuses.

Labour

Businesses should uphold the freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining;

the elimination of all forms of forced and compulsory labour;

the effective abolition of all child labour; and

the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

Environment

Businesses are asked to support a precautionary approach to environmental challenges;

undertake initiatives to promote greater environmental responsibility; and

encourage the development and diffusion of environmentally friendly technologies.

Anti-corruption

Businesses should work against corruption in all its forms, including extortion and bribery.

6.2.1 How does the UN Global Compact work?

Working on concrete issues through networks is an important part of the Global Compact’s activities. Local and regional networks have been established to promote dialogue and the exchange of experience between member companies from all over the world. Since 2000, companies in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Iceland have formed a Nordic network, which meets twice a year to discuss practical experience and dilemmas relating to the principles. The Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise (NHO) was the contact point for the Nordic network from 2005 until 2007, when the Confederation of Danish Industry (DI) took over this function.

The Global Compact’s headquarters are in New York. The office cooperates with other UN bodies, including the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). The Global Compact’s board is made up of representatives from the private sector, labour, civil society and the UN. The UN Secretary-General chairs the board.

The Global Compact has developed a number of tools to demonstrate how businesses can apply the principles. Caring for the Climate is a platform for companies that wish to show leadership in the climate field. The CEO Water Mandate is an initiative aimed at increasing corporate involvement in relation to the global water crisis.

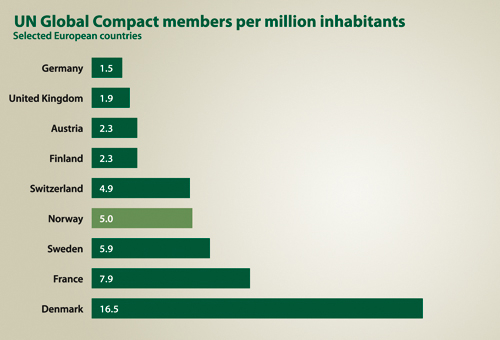

Figure 6.3 Companies in the UN Global Compact.

The Global Compact is partly financed through contributions from the private sector to the Global Compact Foundation. However, the chief source of funding consists of contributions from member countries to a separate Global Compact Trust Fund. The current contributors are Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Germany, France, Switzerland, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, Colombia, China and the Republic of Korea. The network is working to increase support from countries in the South and emerging economies such as Brazil, Russia and India.

6.2.2 What does joining the UN Global Compact entail?

A company joins the network by its chief executive writing a letter the UN Secretary-General stating that the company will make the 10 principles an integral part of its day-to-day operations. Member companies must send an annual Communication on Progress (COP) to the Global Compact. The COP can either be part of the company’s annual report or a separate sustainability report. Companies are also expected to promote the Global Compact externally.

Global Compact has been criticised for its lack of follow-up mechanisms and reporting. It has been pointed out that the principles are merely political commitments that cannot be legally enforced. NGOs claim that many companies become members in order to avoid introducing more binding accountability mechanisms and rules.

Textbox 6.5 What is expected of participants in the UN Global Compact?

A commitment on the part of the company’s management and board of directors

A letter from the chief executive to the UN Secretary-General

Willingness to continuously improve corporate practice

The setting of strategic and operational goals, measuring results and communicating internally and externally

Transparency in relation to dialogue and learning with respect to challenges

Participation in meetings and seminars, locally and globally, and dialogue with stakeholders

Annual reporting: Communication on Progress (COP)

Source The UN Global Compact

Less than 50 % of the members prepared a COP in 2007. If the rest of the world is to have confidence in the Global Compact and its member companies, it is crucial that they document that they operate responsibly. The Global Compact Office now reacts systematically to the failure to report. Companies that have failed to report for three years are de-listed from the Global Compact. In January 2008, 394 companies were removed from the membership register for this reason. The chief executives of 78 companies received a written warning for failure to report. Companies that submit outstanding reports are given positive feedback.

Global Compact was never intended to be a binding instrument where breaches of the principles can result in legal sanctions. The purpose of the Global Compact has been to create a UN-based international corporate network to promote work on CSR in practice. It is necessary to work in parallel to develop other, more binding frameworks.

Textbox 6.6 Declaration by the leaders of the G8 countries at the Heiligendam summit in 2007

«We stress in particular the UN Global Compact as an important CSR initiative; we invite corporations from the G8 countries, emerging nations and developing countries to participate actively in the Global Compact and to support the worldwide dissemination of this initiative.

In order to strengthen the voluntary approach of CSR, we encourage the improvement of the transparency of private companies’ performance with respect to CSR , and clarification of the numerous standards and principles issued in this area by many different public and private actors. We invite the companies listed on our Stock Markets to assess, in their annual reports, the way they comply with CSR standards and principles. We ask the OECD, in cooperation with the Global Compact and ILO, to compile the most relevant CSR standards in order to give more visibility and more clarity to the various standards and principles.»

It is still a challenge to get companies to realise the practical usefulness of the Global Compact and to get more companies to join. Through increased support for and concrete work on the 10 principles, the private sector can make the Global Compact an important factor in global development.

The Government

attaches importance to the efforts to strengthen the Global Compact as an important global framework for CSR, and it will continue to contribute financially to the initiative;

will cooperate with the private sector to increase knowledge about the Global Compact and encourage more companies to join the initiative;

will, through donor meetings, discuss how the donor countries can help to strengthen and further develop the Global Compact.

6.3 The Global Reporting Initiative

The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is a voluntary international network based on cooperation between companies, employees’ organisations, investors, auditors, NGOs, academics and other stakeholders. The network has affiliated UN status as an institution that cooperates with the UN Environment Programme, UNEP.

The objective of the GRI is to make reporting on the triple bottom line, i.e. economic, environmental and social outcomes, as widespread as normal financial reporting is today. The GRI has developed principles and indicators for such reporting, and it is the most widespread international framework of its kind. The framework is suitable for companies and organisations in different sectors. More than 1 000 enterprises in 60 countries currently use the GRI.

The GRI network works on development and improvement of the Guidelines and aims to increase their use. The G3 Guidelines are the cornerstone of the framework. Launched in 2006, they were the result of three years of consultations with 3 000 representatives from various stakeholder groups.

The GRI is supported financially by the Dutch, British, German, Swedish and Australian authorities, the EU, major industrial companies and other private and public donors. Norway became a donor in 2008.

6.3.1 What does GRI reporting entail?

The GRI framework describes why, how and about what an organisation should report. Eleven principles provide guidance on the report’s contents and quality, and they include sustainability, comparability, clarity and reliability. In addition to the principles, the report is to state how far the company has complied with the Guidelines at which level (A, B or C) of performance. External verification of the report is encouraged, but is not a requirement.

The GRI also recommends that the reporting should include the company’s vision and strategy for contributing to sustainable development, and describe the company’s profile, activities and stakeholders. It should also describe the company’s governance structure and management system.

The GRI consists of more than 80 indicators for economic, social and environmental performance. Within each area, the GRI defines core indicators on which all companies should report, as well as additional indicators that may be used to enrich a report.

The economicindicators concern the company’s financial value creation and other economic effects on society. They cover reporting on wages, pensions and other benefits for the company’s management and employees, payments received from customers and payments made to subcontractors.

The environmentalindicators deal with the company’s impacts on the environment, ecosystems, soil, air and water. The indicators include environmental impacts of the company’s products and services, resource consumption, the consumption of environmentally hazardous substances and raw materials, emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants, waste, costs of environmental investments, and fines and penalties for violation of environmental legislation.

The socialindicators are grouped into three categories: factors relating to employees; to human rights; and to more general social issues concerning consumers, local communities and other stakeholders. Such information can be difficult to quantify. In some cases qualitative descriptions may be permitted.

GRI reports should be prepared annually and published on the internet. GRI reporting is voluntary and free of charge. Companies can choose whether they wish to use the guidelines in their entirety or in part, or use them as a reference.

The GRI guidelines are continually being developed and improved. Sector supplements have been produced that are intended to supplement the core guidelines. The framework also targets small and medium-sized enterprises, and a guide has been produced to simplify reporting by such companies. The GRI has also developed a protocol for defining reporting responsibility down though the value chain, and it is working on tools to be used by suppliers. It has also launched a network for transparency in the supply chain.

6.3.2 The value of reporting

Transparent reporting heightens the focus on economic, social and environmental factors. It motivates companies to intensify their efforts in relation to CSR and can help to improve compliance with UN and OECD principles and standards. The Global Compact recommends that the GRI be used in the preparation of the annual Communication on Progress to the Global Compact. The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprisesencourage companies to apply high quality standards to non-financial reporting, including information about environmental and social factors.

The use of a single template for reporting is advantageous for companies, authorities and organisations since it systemises documentation and makes it more readily comparable. The GRI template is currently the most important tool for international comparison of companies’ results.

Large companies in Norway use the GRI as a reporting template and consider it a necessary tool in their operations. The reporting helps to systemise companies’ work on CSR, and the process helps to increase awareness within companies of the challenges and the potential for improvement. What a company measures can be controlled, and what can be controlled can be changed. Reporting is thus a useful tool in companies’ ongoing efforts to improve their operations.

Some companies claim that the number of indicators and the scope of the reporting make them less user-friendly. Others claim that GRI reporting is expensive and best suited to large companies with extensive resources at their disposal. Experience shows that it is important that companies use those parts of GRI that are relevant to them and apply the framework flexibly.

The Government

views the GRI as a useful basis for reporting on economic, social and environmental factors, particularly for large companies;

will help to improve information and guidance about the GRI;

will join the donors supporting the GRI, with particular emphasis on increasing the relevance of the GRI in developing countries;

will support the GRI’s work on developing reporting tools that are adapted to small and medium-sized enterprises.

6.4 Standardisation and certification

Most of the reporting schemes have in common that they are voluntary and that they are seldom verified. It is possible, however, for a company to have its report externally audited. Independent certification will enable companies to demonstrate their social responsibility to consumers and other stakeholders. This applies in particular to companies in developing countries that need to show consumers that they uphold high standards. Certification can also be useful in identifying strengths, weakness and potential for improvement.

SA 8000 is currently the only certifiable standard that includes international human rights and labour rights. The standard builds on the same basis as the established ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 standards for quality and environmental management and control. The AA 1000 standards are templates for dialogue with stakeholders and a standard with methods for verifying reports on CSR (AA 1000as). Det Norske Veritas offers certification of companies in accordance with SA 8000 and verification based on the GRI and AA 1000as.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) decided in 2004, in consultation with various stakeholders, to develop an international guiding standard for organisations’ social responsibility (Guidance on Social Responsibility), called ISO 26000.

The standard, which is scheduled for completion in the autumn of 2010, will apply to all types of organisations, in both developing and industrialised countries. It will contain guidelines and recommendations for how organisations should exercise their social responsibility, and will cover topics such as corporate governance, human rights, labour standards, the environment, consumer issues and participation by local communities.

Textbox 6.7 Certification schemes and standards

SA 8000 is a certification standard for the exercise of social responsibility in nine areas: child labour, forced labour, workplace health and safety, freedom of association, discrimination, disciplinary practice, working hours, remuneration and management systems. It is based on several existing human rights standards, including the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the ILO Conventions.

ISO 14001 is an international standard for environmental management systems in organisations of all kinds. The first step towards certification is an assessment to identify any significant environmental impact by the company, and relevant improvement measures. An environmental policy and an action plan containing environmental targets and deadlines are then drawn up on the basis of the assessment. In order to achieve the environmental targets, a management system must be introduced, including procedures, reporting routines and a division of responsibility. The organisation must work continuously to reduce its environmental impact.

The Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) is a voluntary environmental registration scheme for organisations in the EU and the EEA. As a management tool, EMAS is most relevant to organisations that have a European market. EMAS is based on ISO 14001, but has expanded requirements in the following areas: statutory environmental requirements, environmental performance, communication with the general public and employee participation.

Miljøfyrtårn (Eco-Lighthouse) is an official Norwegian certification system that aims to improve environmental performance in the private and public sectors, particularly in small and medium-sized enterprises and organisations. Companies and organisations that submit to an environmental analysis and meet defined sector requirements can obtain eco-lighthouse certification. The analysis covers HSE, purchasing, waste, energy and transport, as well as environmental and climate reporting. So far, more than 1 300 private enterprises and public sector entities have been certified.

The standard will be consistent with other existing ISO standards, and its normative content is drawn from relevant international declarations, agreements and conventions developed by the UN and UN agencies, including the ILO. The use of ISO 26000 will be voluntary.

The process of developing ISO 26000 is already contributing to existing efforts within the area of social responsibility by:

developing international consensus on concepts and central issues relating to social responsibility, and issues that various different organisations must take a position on;

providing guidelines for how general principles for social responsibility can be translated into concrete action;

identifying examples of best practice, from both the private and the public sector.

The process of developing the standard is probably the most extensive ever carried out under the auspices of the ISO. The standard is being developed by a broad-based working group comprising representatives from the authorities, the private sector, workers’ organisations, NGOs, consumers, academia, service providers and others. A majority of the 84 countries currently participating in this work are developing countries. This is unique in the ISO context. In addition, roughly 40 organisations such as the OECD, UNCTAD, WHO, ILO, the UN Global Compact, the GRI and Consumers International are involved in the work. Standards Norway is coordinating Norwegian efforts and has appointed a mirror committee that discusses and provides input to the Norwegian delegation.

The development of an ISO standard, which is now in its final phase, is being followed with interest. In the Government’s view, the process will be worthwhile if it results in a standard that gains global acceptance. However, there is still uncertainty about the status of such a standard. With so many countries involved and the requirement of consensus, the final result may well be the lowest common denominator. The importance of ISO 26000 will probably vary from country to country. It will depend to a great extent on the final wording of the standard and the experience of and interest shown by opinion leaders.

The Government

is participating actively in the development of ISO 26000;

is of the view that the process of developing an international guiding standard for social responsibility will represent an important step in the direction of a common international framework.

6.5 The need for international guidelines

In principle, corporate compliance with the guidelines and standards described in this chapter is voluntary. The Government expects Norwegian companies to base their international operations on such guidelines and standards.

In the Government’s view, it is important that the international efforts to make the framework for social responsibility more binding and ensure that it includes monitoring mechanisms are continued. The Government intends to play a proactive role in efforts to strengthen such mechanisms in the UN and OECD. In relation to the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, this is being done through efforts to reinforce the role of the NCPs. Several of the initiatives described in this chapter are therefore somewhere between purely voluntary and binding. Joining them is a voluntary matter but, once a company has joined, compliance with the requirements is subject to control.

Such initiatives are therefore often characterised as «soft law» instruments and, in principle, they can be further developed with respect to grievance mechanisms, documentation and transparency requirements and sanctions. The broad proliferation and consequent harmonisation of requirements for such instruments can pave the way for legal instruments whose introduction would otherwise have been demanding and controversial.

In the Government’s view, «soft-law» instruments are of great importance in driving developments forward. Such instruments can clarify requirements and expectations and facilitate a coordinated effort on the part of the private sector, the authorities and NGOs. Such initiatives can, not least, stimulate voluntary participation in schemes for effective verification of compliance with the requirements. It is important that companies obtain information about these instruments and guidelines and apply those that are most suited to their operations.

The Government will participate actively in efforts to consolidate, further develop and increase adherence to international frameworks that, in various ways, promote social responsibility and transparency in the private sector. The Government will support efforts to further develop and realise synergies between the different standards and principles of the UN, the OECD and ILO.

The Government views the development of international frameworks for the private sector’s operations as the best solution for governing the global economy and addressing fundamental challenges facing society. International norms and standards also help to ensure equal conditions of competition. International processes that can influence the framework for the private sector’s operations are discussed in the following chapter.