2 Ambition

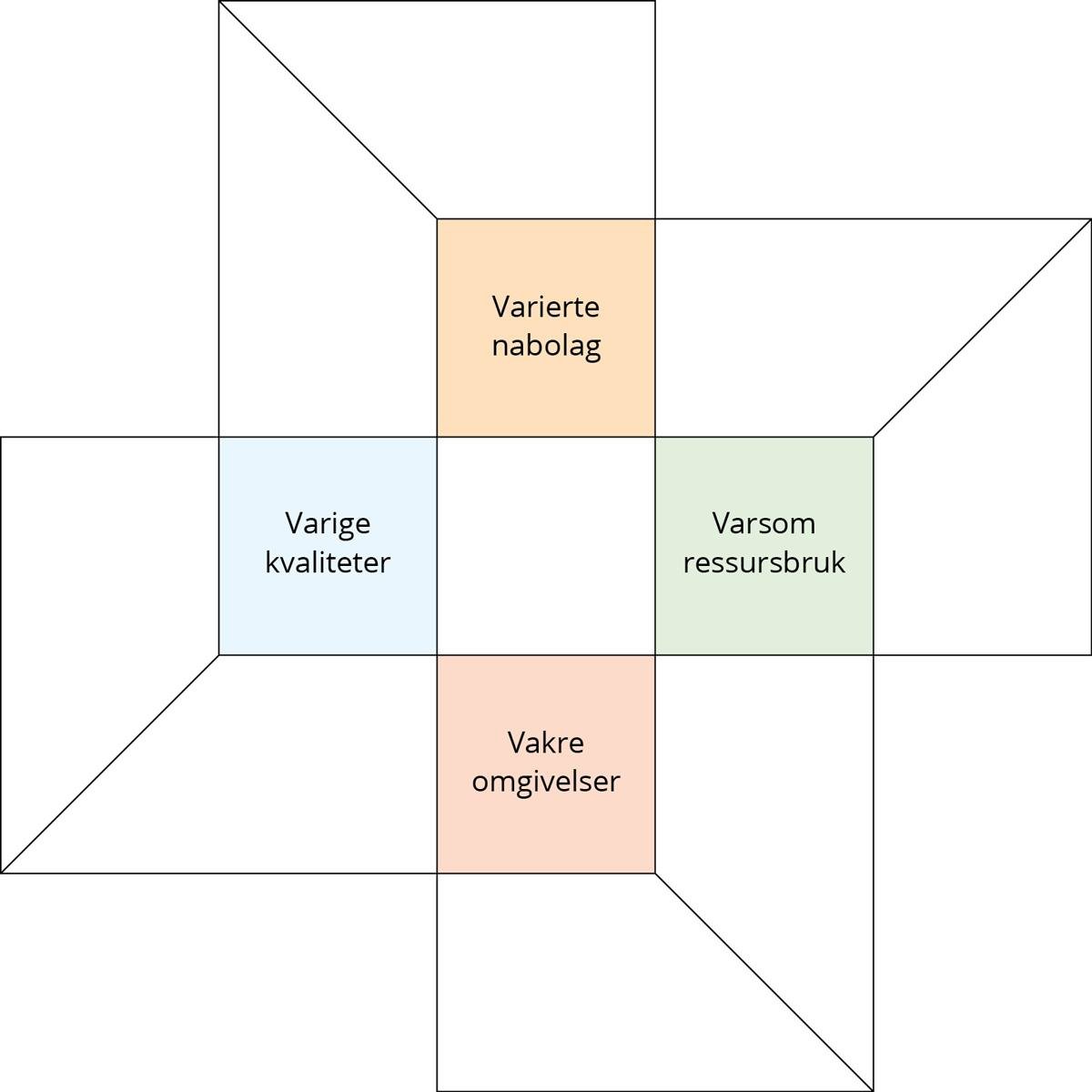

The Government’s ambition is that we collectively manage and develop architecture with varied neighbourhoods, a prudent use of resources, beautiful surroundings and enduring qualities.

These are the strategy’s four focus areas and can also be used as a tool for discussing what constitutes architectural quality – in overarching planning processes, local strategy work, or in zoning plans and building applications.

Vindmøllebakken , Stavanger. Developer: Kruse Smith Eiendom AS/Helen & Hard AS. Architect: Helen & Hard AS Photo: Sindre Ellingsen

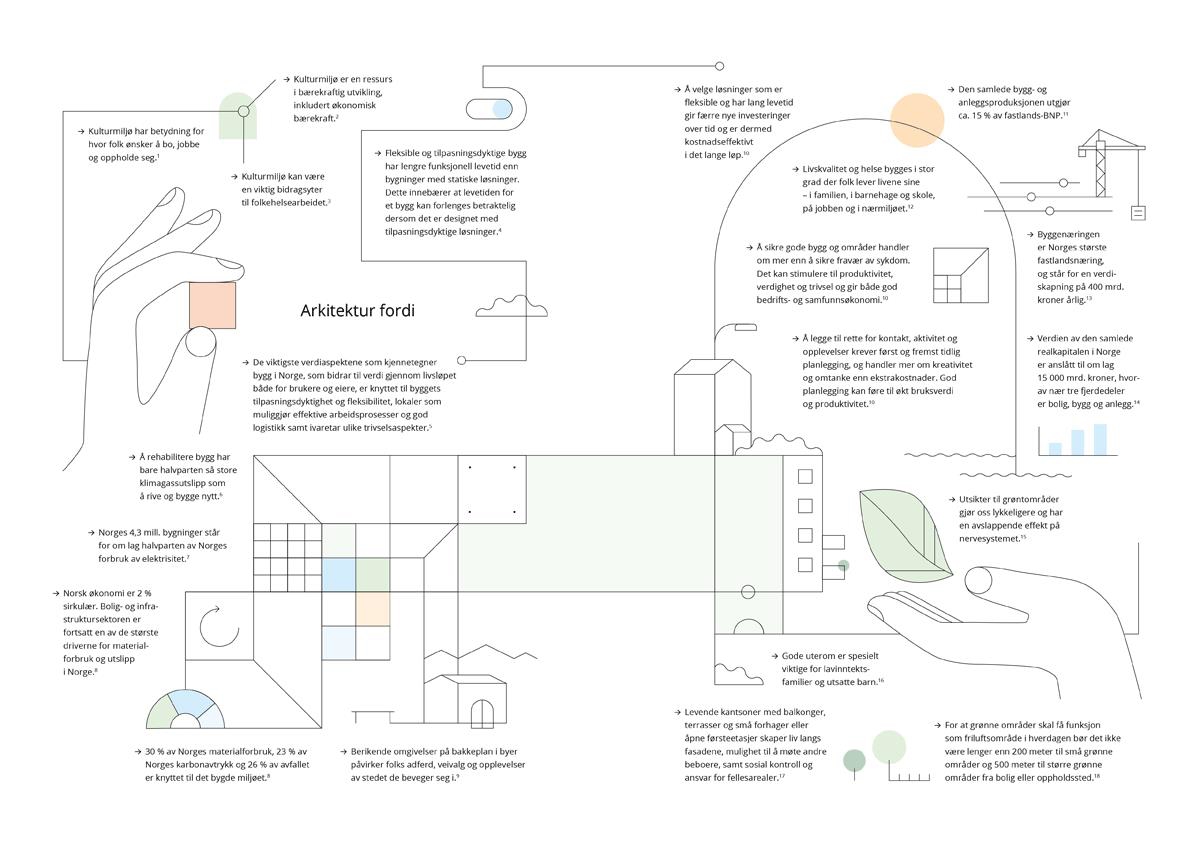

Architecture because

- Cultural environments influence where people want to live, work and spend time. 1

- Cultural environments are a resource in sustainable development, including economic sustainability. 2

- Cultural environments can be an important contributor to public health work. 3

- Flexible and adaptable buildings have a longer functional lifespan than buildings with static solutions. This means that the lifespan of a building can be significantly extended if it is designed with adaptable solutions. 4

- The key aspects of value that characterise buildings in Norway, which contribute to value throughout their lifecycle for both users and owners, are linked to the building’s adaptability and flexibility, premises that enable efficient work processes and logistics, and safeguard various aspects of wellbeing. 5

- Rehabilitating a building produces only half the greenhouse gas emissions compared to demolishing and building anew. 6

- Norway’s 4.3 million buildings account for around half of the country’s electricity consumption. 7

- The Norwegian economy is 2 % circular. The housing and infrastructure sector remains one of the largest drivers of material consumption and emissions in Norway. 8

- 30 % of Norway’s material consumption, 23 % of Norway’s carbon footprint and 26 % of waste relate to the built environment. 9

- Enriching environments at street level in towns and cities influence people’s behaviour, route choices and experiences of the places through which they move. 10

- Choosing solutions that are flexible and have a long lifespan reduces the need for new investments over time and is therefore cost-effective in the long run. 11

- The total building and installation output accounts for around 15 % of mainland GDP. 12

- Quality of life and health are largely shaped by where people live their daily lives – with their family, in kindergartens and schools, at work and in their local community. 13

- Ensuring good buildings and spaces is about more than preventing ill health. It can stimulate productivity, dignity and wellbeing, and contributes to both sound corporate and socio-economic outcomes. 14

- The construction industry is Norway’s largest mainland industry, accounting for value creation of NOK 400 billion annually. 15

- Facilitating contact, activity and experiences requires first and foremost early planning, and is more a matter of creativity and thoughtful consideration than additional costs. Good planning can increase utility value and productivity. 16

- The total fixed assets in Norway are estimated to be around NOK 15,000 billion, of which nearly three-quarters is housing, buildings and installations. 17

- Views of green space make us happier and have a relaxing effect on the nervous system. 18

- Good outdoor areas are particularly important for low-income families and vulnerable children. 19

- Lively building exteriors, with balconies, terraces and small front gardens, or open ground floors, create life along facades, opportunities to meet other residents, and foster community supervision and responsibility for common areas. 20

- For green spaces to function as everyday recreation areas, small green spaces should be no further than 200 metres from housing or other frequented places, or 500 metres for larger green spaces. 21

Varied neighbourhoods

The Government’s ambition is that we collectively plan and develop inclusive towns, cities and residential areas that meet society’s diversity. Built environments that preserve blue and green natural elements, parks, squares and public meeting places promote health and quality of life. Architecture should contribute to lasting social sustainability and community in diverse urban areas and neighbourhoods .

Krydderhagen , Oslo. Developer: Haslemann AS. Architect/Landscape architect: Dyrvik Arkitekter AS/Grindaker AS. Photo: Stine Østby

Diverse housing and living environments

The Government has presented a white paper on a comprehensive housing policy 22 in which one of the focus areas is to preserve existing housing and build the homes that are needed. Architecture is an important tool for achieving this goal. The Government is committed to ensuring that the construction of new homes complements the existing housing market, so that overall, the housing supply meets our needs. In many parts of Norway, there is a need to build more housing to meet the growth in the number of households, and the Government aims to initiate the construction of 130,000 dwellings by 2030.

Social and land-use planning should contribute to social sustainability in towns, cities and local communities, in tandem with economic and environmental sustainability. Municipalities, as planning and building authorities, are responsible for facilitating sufficient housing development, well-designed built environments, and favourable living and childhood environments. Consistent quality between residential areas, and a varied housing composition within areas, can contribute to choice in the housing market and diversifying neighbourhoods.

A varied housing supply is essential to meeting the different needs of the population. It is important that children and young people live in good housing conditions, that young people can establish themselves in the housing market, that newly arrived employees have a place to live, and that the elderly and those with functional impairments have access to suitable housing.

As planning authorities, municipalities can influence housing composition through the number of dwellings, their types and sizes, and through various investments that can increase attractiveness. Capacity, competence and finances may, however, be barriers to using the available instruments. The Government will strengthen the knowledge base that municipalities need for planning housing, and their competence in this area. The Norwegian State Housing Bank (Husbanken) has been assigned a new social mission – to strengthen and develop its supportive role to municipalities in their comprehensive housing policy work.

Architecture should be designed so that as many people as possible can use buildings and outdoor spaces, regardless of functional ability. Private and public enterprises that serve the general public must be designed for universal accessibility. For dwellings, the principle of universal accessibility must be implemented in line with accessibility requirements. Universal design is also important in light of an ageing population, where many experience functional challenges with increasing age. The Government’s work on universal design is implemented through action plans.

In the white paper Fellesskap og meistring – Bu trygt heime 23 (Community and mastery – Living safely at home), age-friendly and inclusive communities with housing adapted to the needs of the elderly are an important focus area. The national programmes for age-friendly cities and communities 2030, aimed at people over the age of 55 develops measures to raise awareness and demonstrate how individuals can plan for a better old age in line with their wishes, and how municipalities, businesses and voluntary organisations can contribute to more age-friendly communities. Most people want to remain in their own homes as long as possible, even with reduced health and functional ability, and many are able to prepare for this themselves, before challenges arise.

In line with the white paper, the Government has established a senior housing programme that aims to ensure everyone has access to a suitable dwelling in an age-friendly living environment, and to encourage more senior citizens to take responsibility for and be aware of their housing situation. The Government will work together with municipalities, the industry and the Norwegian State Housing Bank to adapt the provision going forward. The senior housing programme provides direction and a framework for comprehensive action and is intended to be a flexible framework that can incorporate new measures along the way. The Norwegian State Housing Bank has overall responsibility for implementing the programme, in close collaboration with other actors. The measures are intended to enable municipalities to unlock the potential of good guidance and planning, encourage individuals to plan their own housing situation, and explore the possibilities of new and more social forms of housing. Through loans for the construction of lifelong housing, the Norwegian State Housing Bank also supports the development of high-quality housing where the requirements for accessible occupancy units are met.

New and more social forms of housing will be important elements in future urban and local development. Common areas can create new arenas for interaction, community and belonging. An increase in the senior population and people living in single-person households may increase demand for alternative forms of housing. There are many good examples of projects where solutions have been developed to facilitate shared and communal solutions. The Norwegian State Housing Bank plays an important role as a supporter of municipalities and as a driving force for new trials, improvements and innovations. Grants for housing projects enable actors to test new solutions in housing for welfare initiatives. The grants are intended to stimulate knowledge development and innovation in response to demographic, economic and social challenges, with the overarching goal of facilitating suitable dwellings throughout the country.

In the long-term plan for the defence sector 24 , the Government has set ambitions for the Norwegian Armed Forces to provide good living and working conditions to conscripts and employees in municipalities with defence responsibilities, to prioritise good living environments in rural areas and to integrate these living environments into local communities in cooperation with each municipality. The Government will also facilitate that more people settle in municipalities with defence responsibilities. The Centre of Competence on Rural Development is conducting a pilot project for cooperation between municipalities with defence responsibilities and the Armed Forces in Sør-Varanger, Bardu and Målselv. The Centre of Competence on Rural Development provides assistance to actors to strengthen local cooperation on housing development and the development of attractive places. The project will be subject to follow-up research and will provide important knowledge about how municipalities and state actors can collaborate on local development and housing.

Dronning Ingrids hage , dementia village, Oslo. Client: Omsorgsbygg. Architect/Landscape architect: Arkitema K/S/White arkitekter AS. Photo: Sindre Narvestad

Good frameworks for quality of life and community

Good architecture is both health-protective and health-promoting, as it stimulates daily movement, physical activity and facilitates participation, inclusion and community. The Government is committed to ensuring that municipalities facilitate compact urban development with short distances between dwellings, workplaces, blue-green infrastructure and other green areas, leisure facilities and environmentally friendly modes of transport.

Many smaller urban and rural centres have potential for increased densification and transformation. Currently, there is often more scattered development in many urban centres, with large parking areas and empty buildings. Densification and transformation should contribute to community solutions, mixed-use and reuse. In addition, it is important that densification provides variation in housing types adapted to municipal demographics, is based on the scale of the site and that national guidelines are adapted to local conditions and needs. Access to apartments and proximity to services and amenities can be especially attractive to an ageing population and others who want easier-to-maintain dwellings and simpler lives.

A good number of leisure homes are built in connection with densely populated areas and travel destinations. Leisure homes should ideally also be planned as densification. The location and design of leisure homes and their associated central amenities should follow the principles of sustainable urban development, with compact centres, and buildings and outdoor spaces with architectural quality adapted to the site and its surroundings.

The built environment can influence how we feel and the choices we make. The Government is committed to ensuring that urban areas and neighbourhoods have sufficient and varied public spaces and common areas. In addition to variety in the housing supply, neighbourhoods need access to social infrastructure such as kindergartens, schools, and cultural and leisure facilities, good official public spaces, blue and green areas and varied meeting places.

In their planning, municipalities should set aside space for both commercial and non-commercial meeting places. Planning should safeguard both outdoor public spaces such as squares and parks, and indoor common areas such as libraries, sports halls, cultural venues and community centres. Public spaces and meeting places enable people to meet across generations and backgrounds. Areas used by different groups, where children and young people, adults and the elderly encounter one another, can contribute to safety and cohesion in neighbourhoods. Mixed-use buildings allow for a diversity of activities and can make areas attractive both during the day and in the evening. The Government contributes to increasing knowledge by gathering good examples and disseminating experiences about the importance of good meeting places, co-use and mixed-use buildings and outdoor spaces.

Ensuring good qualities in the physical environment is important to achieving good public health, and municipalities need to take this into consideration in their planning. In recent years, the Government has presented several strategic documents on public health policy: Folkehelsemeldinga 25 , Handlingsplan for fysisk aktivitet 2020-2029 26 (Public health white paper: Action Plan for Physical Activity 2020-2029) and a proposal to the Storting (the Norwegian Parliament) on amendments to the Public Health Act. 27 The purpose is to promote health and quality of life, sustainable social development and to help reduce social health inequalities.

The Government has presented the white paper Good Urban Communities with Small Differences 28 , which gathers policies and instruments to maintain and strengthen social sustainability in towns, cities and neighbourhoods. In areas where living conditions are challenging, it is particularly important to promote good local environments and develop attractive outdoor spaces. In the area-based initiatives, where the Government has agreements with selected towns and cities on extra efforts in disadvantaged areas, the focus is on improving the physical and social qualities of local communities. The municipalities’ work is carried out in cooperation with residents and civil society. The Government has significantly strengthened regional initiatives in recent years, and will continue to further develop these efforts. The Government will also strengthen efforts to disseminate knowledge and experience from area-based initiatives across municipalities, including to those that do not currently have such initiatives.

The Government is committed to towns, cities and neighbourhoods being designed with qualities that help prevent crime and allow people to feel their local community is safe. Architecture can help create physical environments that makes it more difficult to commit criminal acts. Projects should be planned and designed with adaption for the local social context. Examples of measures include ensuring safe meeting places, well-structured public spaces that provide functions for different groups of people, with adequate and appropriate lighting.

Havegaten 1 , Tønsberg. Developer: Pilares Eiendom AS. Architect/Landscape architect: Holar Ola Roald AS/Landskapskollektivet AS. Photo: Jonas Adolfsen and Pilares

Vindmøllebakken , Stavanger. Developer: Kruse Smith Eiendom AS/Helen & Hard AS. Architect: Helen & Hard AS. Photo: Minna Soujoki

The Activity Park , Voss. Client: Voss municipality. Landscape architect: Østengen & Bergo AS. Photo: Kari Bergo

Røa torg , Oslo. Developer: Røa Centrum AS. Architect/Landscape architect: LPO arkitekter AS/Norconsult AS. Photo: Amund Johne

Samling bibliotek , Nord-Odal. Client: Nord-Odal municipality. Architect: Helen & Hard AS. Photo: Sindre Ellingsen

Kirkegårdsgata 14/Løkka Botaniske , Oslo. Developer: Cura Eiendom AS. Architect: Enerhaugen arkitektkontor AS. Photo: Ivar Kvaal/Hest Agency

Generalhagen , Harstad. Client: Harstad municipality. Architect/Landscape architect: Asplan Viak AS. Photo: Øivind Arvola

Greener towns, cities and vibrant streets

The Governments is committed to ensuring that urban development and architecture are actively used to make room for nature. In all urban development, it is important to preserve or allocate space for blue and green areas. This can include vegetation and water surfaces in the urban environment, parks and natural areas of sufficient size to provide recreation and nature experiences in daily life, and a physical development pattern with distances that ensure easy access to surrounding outdoor recreation areas and other nearby natural areas. Trees and other vegetation create vibrant and pleasant surroundings, and can invite recreation or activity. Proximity to nature has a positive impact on people’s quality of life and health.

Blue-green structures are important to adapting towns and cities to a changing climate. Trees that provide shade contribute to temperature regulation. More frequent and heavier rainfall will require a new ways of handling surface water and flooding, particularly in urban areas with a lot of impermeable surfaces and a great deal of property at risk of damage. Planning and construction must be carried out with resilient solutions that meet these changing challenges. The Government is committed to ensuring that urban development and climate change adaptation take place on nature’s own terms, as set out in the national planning guidelines for climate and energy. 29 Planning should relate to nature and the landscape’s topography, watercourses and biodiversity. Using nature-based solutions such as trees, sunken retention basins, and rain gardens in public spaces and streets to manage surface water makes urban areas more robust and durable. Green roofs, parks and waterways effectively manage storm water from precipitation, mitigating the effects of extreme events such as heatwaves and heavy downpours.

Natural and cultural environments are seen in context when discussing green towns, cities and urban areas. Most of the nature around us has been affected by human use throughout history, and natural terrain can represent important qualities in valuable cultural environments. In towns, cities and urban areas, green spaces and structures often constitute an important part of historic built environments, which may carry narratives about previous planning and past ideals. Together, these environments can provide variety, increased quality of life, a sense of belonging and promote good health. Cultural environments influence where people want to live and often serve as good meeting places, destinations for walks, or starting points for voluntary activities in green and built-up environments.

As planning authorities and landowners, municipalities can greatly influence the design of streets and public spaces. Through various investments in infrastructure, municipalities can help increase the attractiveness of urban areas and neighbourhoods. When planning streets and public spaces, priority should be given to pedestrians, cyclists and blue-green areas, alongside accessible and reliable public transport. Municipalities can use various tools to discuss and establish the frameworks for public spaces and street design, such as guidelines on street standards, street-use plans and urban-space strategies.

The Norwegian Public Roads Administration has a special responsibility for safeguarding the overall coherence of the road sector, and develops regulations and standards that apply to the sector. The Norwegian Public Roads Administration and Nye Veier AS must both use good architectural and aesthetic quality in their own projects, making it simple and attractive to walk, cycle and use public transport. The design of streets in towns, cities and urban areas should be adapted to the local context. This is about ensuring coherence in built-up areas through good design of the everyday landscape where people move daily, and creating an equitable transport system. The design of pedestrian and cycle networks, especially school routes, is important to developing social skills and for physical activity.

Thorvald Meyers gate , Oslo. Client: Oslo municipality, the Agency for Urban Environment. Landscape architect: Norconsult AS. Photo: Amund Johne

Verket , Moss. Developer: Höegh Eigedom AS. Architect/Landscape architect: MEI/Lala Tøyen AS/A-lab AS/Mad AS/NIELSTORP+ arkitekter AS/Asplan Viak AS. Photo: Lala Tøyen AS

Lynghaugparken , Bergen. Client: Bergen municipality. Landscape architect: Norconsult AS and Curve Studio AS. Photo: Stine Østby

Vollebekk torg , Oslo. Developer: OBOS Nye Hjem AS. Landscape architect: Studio Oslo landskapsarkitekter AS. Photo: Stine Østby

Hovinbekken , Ensjø, Oslo. Developer: JM Norge AS. Landscape architect: Bjørbekk & Lindheim landskapsarkitekter AS. Photo: Nils Petter Dale

Prudent use of resources

The Government’s ambition is for planning and architecture to contribute to a more prudent use of resources, with development that safeguards cultural environments, climate, natural resources and biodiversity. The built environment is influenced by, and itself influences, climate and environmental challenges. There is a need for architectural solutions that help conserve nature and minimise the environmental impact of construction work, while also ensuring construction costs do not increase.

Sykkylven Public Library . Client: Sykkylven municipality. Landscape architect: LARK Landscape AS. Photo: Kristin Støylen

Efficient land use for nature and climate

Nature is under significant pressure. Encroachment on natural areas causes greenhouse gas emissions and the loss of biodiversity, and it is important to preserve arable land for societal preparedness. In the Climate Report 30 , the Nature Report 31 and the Action Plan for the Circular Economy 32 , the Government emphasised that energy, bio-resources and land are scarce resources that must be utilised efficiently to ensure sustainable development.

In the Nature Report, the Government set a goal of reducing encroachment on particularly important natural areas by 2030, and to limit the net loss of such areas by 2050. This goal forms the basis for central government activity and the work of the Government going forward.

To avoid further encroachment on natural areas, the main principle going forward will be to utilise areas that are already developed and to reuse existing buildings and installations. Towns, cities and urban areas will be developed from within using densification and transformation. This is clarified in the new Government Planning Guidelines for Land Use and Mobility 33 and for climate and energy, which the Government presented in 2024. The guidelines apply to national, regional and municipal planning pursuant to the Planning and Building Act. Municipalities, county authorities and central government must also use the guidelines as a basis for localising their own activities and enterprises.

Through the 2022 Nature Agreement 34 , Norway has committed to a global goal of conserving nature in towns and cities. The Norwegian contribution to this goal was presented by the Government in the Nature Report, with the goal that by 2030, the area, quality and connectivity of green and blue areas and other green infrastructure in towns, cities and densely populated areas shall have increased, and that native species shall be prioritised.

The Government is committed to ensuring that nature is preserved in urban areas even when densifying. Many towns, cities and urban areas have developed in places that are particularly rich in biodiversity. Nature has enormous value for people, but nature and its diversity also have intrinsic value. 35 Nature provides services within its ecosystem, such as air and water purification, cooling, surface-water management and flood mitigation. When transforming former industrial sites and other grey areas, it is essential to develop new natural and green spaces. Sustainable urban development entails preserving existing natural spaces, as well as restoring and developing new blue and green spaces when built-up areas are expanded, densified or transformed.

Municipalities have a key role in preserving natural areas when planning land-use. The Nature Report presents measures that can help strengthen municipalities’ capacity and competence for climate- and nature-friendly planning, such as municipal networks and an assessment of workload-relief teams.

Central government agencies should have sustainable and cost-effective premises that support their purpose. Sustainability must be a guiding principle for the Government’s construction and property activities. Where appropriate, the state should utilise land that is already developed. When the Government leases premises in the market, this should normally be in existing building stock. New premises should be space-efficient. In many cases, existing premises can also be made more space-efficient.

In some cases, it is also necessary for the state to construct new buildings. When the state carries out a construction project, social and performance objectives must be achieved cost-effectively. At the same time, functionality is necessary for the agency that will benefit from the architectural solutions. To ensure an effective use of resources over time, architecture should take into account that the needs addressed by a building may differ in the future. In addition, circular solutions should be considered, both in terms of utilising reusable materials and facilitating future reuse and repurposing.

Vertikal Nydalen , Oslo. Developer: Avantor AS. Architect/Landscape architect: Snøhetta AS/Lala Tøyen AS. Photo: Lars Petter Pettersen/Snøhetta

Fabrikken 59 , Bergen. Developer: BOB. Architect: Vill Arkitektur AS. Photo: Stine Østby

Sustainable mobility and energy efficiency

In line with new Central Government Planning Guidelines for Land Use and Mobility, new physical development areas must be located with a view to minimising the need for transport, facilitating public transport, cycling and walking, and making use of and preserving existing buildings and infrastructure where available. Attention should be given to place-based design and architectural quality, preserving the distinctive character of the place, any cultural-historical elements and important landscape features.

In urban areas, targeted initiatives have been introduced over time to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, congestion, air pollution and noise through efficient land use and by ensuring that growth in passenger transport is absorbed by public transport, cycling, and walking – known as the zero-growth target. To date, urban growth agreements have been made between the Government, county authorities and municipalities in seven urban areas, and these are based on this target. The agreements encourage the parties to consider the relationship between land use and transport in their planning. Efficient land use with densification around transport hubs is an important means of achieving development in line with the zero-growth target.

The National Planning Guidelines for Land Use and Mobility specify that the majority of growth in areas with urban growth agreements must take place in or near major public transport hubs within the agreement area.

Public transport hubs such as railway stations have historically been centrally located in many towns, cities and urban areas in Norway, and the state-owned company Bane NOR Eiendom AS develops and manages several of these areas. Attractive, environmentally friendly and context-sensitive central areas containing mixed-use developments enable short travel distances and travel by public transport, bicycle and walking.

The location and design of facilities and functions can have a significant impact on residents’ ability to make good climate and environmental choices. Co-use and mixed-used spaces, short distances to general amenities and activities, and other strategic approaches to urban and local development can support the possibility of living sustainable lives in a low-emission society.

The design of buildings and local environments can also contribute to energy efficiency and the production of renewable energy. Buildings designed in ways that prevent heat loss, that ensure solar gain, provide sustainable lighting and flexible energy solutions contribute to efficient energy use. In line with central government planning guidelines for climate and energy, energy-efficient solutions and flexible energy sources should be facilitated. The municipality has an important role to play in that respect, by having an overview of the possibilities for heating and cooling based on local energy sources, such as surplus heat. The Norwegian Building Authority will put forward proposals for public consultation to amend the energy and climate requirements in the building regulations. Key goals are to promote more energy-efficient buildings and more climate-friendly construction work.

The low-emission society of the future requires that construction and installation projects be carried out emission-free and with materials that have a low climate footprint. Buildings must be operated and use energy efficiently, and contribute to a well-functioning energy system across sectors. The state-owned enterprise Enova is an instrument for promoting innovation and the development of new climate and energy solutions. Support from Enova is intended to reduce risk and costs for the first to test new solutions.

Krydderhagen , Oslo. Developer: Haslemann AS. Architect/Landscape architect: Dyrvik Arkitekter AS/Grindaker AS. Photo: Stine Østby

Storgata , Mysen. Client: Indre Østfold municipality. Landscape architect: Norconsult AS. Photo: Amund Johne

Skilpaddeparken , Mortensrud, Oslo. Client: Oslo municipality, the Agency for Urban Environment. Landscape architect: PIR2 AS and Bar Bakke AS. Photo: Tove Lauluten

More reuse and transformation

The construction industry is Norway’s largest mainland industry and an important contributor to the transition to a low-emission society. It is vital that the construction industry is innovative and adopts new solutions, not only to achieve climate targets but also to keep construction costs down. Large amounts of materials and resources are tied up in the built environment, and a mindful use of these resources is of huge importance to both the economy and the environment. Construction work involves extensive use of natural resources and produces a significant overall climate footprint. The largest share of the emissions from the Norwegian construction industry are indirect emissions from building materials and construction products. Transforming older building stock, reusing buildings and building materials, or choosing new materials with a smaller climate footprint, can therefore have a major impact on the climate and environment.

Reducing the use of materials by, for example, using slimmer structural members, is a measure that reduces both greenhouse gas emissions and cost. Cross-laminated timber is a material with low greenhouse gas emissions. Experience from projects that use cross-laminated timber shows that construction time is also significantly reduced, resulting in lower investment costs. 36

Most of the homes we will live in have already been built. By maintaining and upgrading residential buildings, homeowners and residents ensure that scarce resources are utilised and that dwellings are adapted to the present needs and challenges related to climate and the environment, energy use and demographic development. The Government is following up on the housing policy white paper and will facilitate that buildings have a longer lifespan by, for example, assessing how building regulations can better enable measures in existing buildings, by renewing the Norwegian State Housing Bank’s loans for upgrading, and by obtaining a better overview of vacant dwellings.

The Norwegian State Housing Bank provides loans for high-quality housing, for the construction of environmentally friendly homes. To qualify for a loan for environmentally friendly housing, stricter requirements must be met than those set out in the Regulations on Technical Requirements for Construction Works. The loan scheme is one of several instruments that can contribute to market development in environmentally friendly housing development. The loan scheme operates in interaction with technological developments, demand for environmentally friendly solutions, regulatory developments and other public framework conditions. The Government will renew the criteria for loans for environmentally friendly housing.

Planning and building legislation sets out a number of rules designed to ensure high-quality construction, including rules on inspection, supervision and qualification requirements. Despite comprehensive regulations, construction errors and building defects still occur. The Government is therefore considering amendments to these rules, to ensure better compliance and create a simpler and more understandable regulatory framework.

Transformation and the reuse of buildings and installations are important elements in a climate and environmentally friendly architectural policy. In line with the new Central Government Planning Guidelines for Climate and Energy, municipalities, as planning authorities, must engage in dialogue with developers on whether the rehabilitation and reuse of buildings is a more sustainable solution for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and resource use than demolition and constructing anew.

In 2024, the Government entered into a climate partnership with the construction industry that sets out the industry’s clear ambitions and the state’s contribution. The state’s contribution is to provide support for knowledge development and involving the industry in the development of new regulations.

There is a need to develop new techniques and products, and more circularity. In a circular economy, resources such as building materials are utilised for as long as possible so that as little as possible is lost. Products need to be durable, to be repaired, upgraded and reused to a greater extent.

The Government has taken several steps to stimulate and facilitate increased circularity in the construction industry. Owing to the technical and regulatory challenges associated with transformation, the Government introduced amendments to the Planning and Building Act in 2023 to make it easier to alter buildings and ensure more sustainable and efficient reuse of buildings.

In 2022, amendments were made to the regulations concerning the documentation of building materials, making it easier to sell used materials for reuse in another building. In the Regulations on Technical Requirements for Construction Works, the minimum requirement for sorting waste on construction sites was increased from 60 to 70 percent, requirements were introduced for new buildings to be designed for later dismantling, and that materials must be mapped for reuse when changes are made to existing buildings. The Government will follow up on the effectiveness of these regulations and the possibilities for further development. We know, for example, that in many instances, waste sorting at construction sites is significantly higher than the minimum requirement.

In spring 2024, the Government presented an action plan for the circular economy. Based on the action plan, an expert group was established to investigate instruments to promote circular activities, and a new social mission for the circular economy has been assessed. Work is now underway on further detailing the social mission.

The expert group investigating instruments to promote the circular economy submitted its report to the Minister of Climate and Environment in May 2025. In its report, the expert group recommended that EU/EEA regulations relating to the transition to a circular economy in the construction, installation and real-estate industry be implemented in Norway on an ongoing basis and as quickly as possible. Furthermore, they recommended that authorities develop a strategy to promote the reuse of used and recycled building materials, that requirements are introduced in the Regulations on Technical Requirements for Construction Works for a maximum climate footprint per square metre in buildings, and that design requirements for dismantling buildings are made more stringent. A total of 11 recommendations were made by the expert group related to this sector.

Skostredet 3-5 , Cultural Heritage Management office, Bergen. Client: Bergen municipality. Architect/property developer: Arkitektstudio Elfrida Bull Bene AS/Pallas AS. Photo: Trond Isaksen/The Directorate for Cultural Heritage.

Kristian August gate 13 , Oslo. Developer: Entra ASA. Architect/Landscape architect: Mad AS/Asplan Viak AS. Photo: Kyrre Sundal/Mad arkitekter AS

Nedre Vollgate 4 , DOGA office, Oslo. Architect/interior architect: DOGA/Sane AS. Photo: DOGA/Einar Aslaksen

Hasle Tre , Oslo. Client: Höegh Eiendom AS. Architect/Landscape architect/Interior architect: Oslo Tre AS/Grindaker AS/I-d. Interior Architecture & Design AS/Romlaboratoriet. Photo: Moritz Groba/Oslotre

Beautiful surroundings

The Government’s ambition is that buildings, neighbourhoods, towns and cities are developed that are beautiful and enriching for people and the environment – to increase quality of life. The built environment constitutes an important part of our cultural heritage, and architecture tells of our history and social development. What is built today may become tomorrow’s cultural heritage. Knowledge about the significance and value of architecture should be illuminated and communicated through broad public debate.

Wesselkvartalet , Asker. Developer: Wesselkvartalet AS. Architect/Landscape architect: Vigsnes + Kosberg++ arkitekter AS/Gullik Gulliksen AS. Photo: Nils Petter Dale

Safeguarding aesthetic experiences

Architecture is a visible expression of culture and society, painting a clear picture of a society’s priorities at any given time. Architectural quality concerns both technical and functional qualities as well as aesthetic qualities in buildings and our surroundings. These parameters are partly subjective and often difficult to measure, making the discussion of what constitutes good aesthetic quality important but also challenging.

According to the European Landscape Convention, architecture should help highlight the qualities of the landscape, both in urban and rural areas. Architecture is always developed in a site-specific situation and must therefore be assessed based on local conditions and the existing qualities of a place. The adaptation of volumes and materials, scale, the use of colour, preservation of historical traces, and the relationship to the landscape and local building traditions are important issues to be considered in new developments. As we build more densely, quality becomes even more important.

There is no definitive definition of what constitutes good design in a local community or neighbourhood, and the Government is committed to ensuring that solutions are developed based on local, geographical and climatic conditions.

Through the Planning and Building Act, municipalities have the responsibility, instruments and scope to set guidelines for architectural and aesthetic qualities. The aesthetic design of surroundings is an important part of the Planning and Building Act’s statement of legislative purpose, and pursuant to the Act, planning must facilitate the good design of developed surroundings. In line with the Planning and Building Act, every project must be designed and carried out so that it maintains good visual qualities both inherently and with regard to its function and its constructed and natural surroundings and location.

The assessment of what constitutes good and poor aesthetic design is down to the discretion of the municipality. It is therefore important that each municipality has a considered and professionally grounded approach to the aesthetic development in its area. Municipalities can use a variety of tools to discuss and set the overall framework for aesthetic development – such as site analyses, urban-design or architectural strategies, and guides on public space, street-use and building traditions. Clear ambitions for the expected quality, linked to updated land-use plans, form an important basis for dialogue and contribute to increased predictability in planning and building application processes. Several municipalities have had positive experiences with early advisory input and follow-up of projects from municipal city architects.

The Government is committed to ensuring that architecture has qualities that are beautiful and functional, during the course of a day, a year and over time. Good outdoor lighting makes our surroundings safer and more pleasant, and affects how we perceive, read and use our physical environment after dark. The quality of our built environment must therefore not only be assessed from a daylight perspective, but also from how it functions and is experienced during the dark times of the day and year. In operational planning, consideration should be given to how streets, buildings and outdoor spaces function and are experienced during dark periods of the day or year.

We are more inclined to take care of what we like, and what we build today should possess qualities that we want to and are able to preserve in the future. When areas and buildings are transformed, new aesthetics are created – perhaps a different aesthetic to when building new. In transformation areas that contain no clear historical qualities, values or distinctiveness on which to adapt or build upon, it is important to discuss at an early stage the desired quality of place and expression of the planned development.

Architecture can be an artwork in itself, and art and architecture can be used in public spaces to enhance quality and attractiveness. The government agency Public Art Norway (KORO) works at the intersection between art and architecture by producing, managing and presenting art in public buildings and spaces throughout Norway, as well as at Norwegian consulates and embassies abroad. KORO’s Art Programme for Local Communities supports the production of art projects in public spaces and contributes to professional development in the field. Art projects supported by the scheme serve as collaborative arenas for the state, municipalities, property developers, local communities and others, and local and international artists.

As a developer and property manager, the state should be a role model. As an actor with significant influence, the state should lead by example wherever possible. Statsbygg must be a driving force for the industry and in its advisory role to ministries in matters concerning building and leasing. What we build today will be part of the cultural heritage of the future. The legacy of our time should be characterised by functional and sustainable choices. This may apply to both the restoration of existing buildings and entirety new constructions. In both cases, the building should, as far as possible, be adapted to its surrounding cultural environment and interact with existing buildings and landscapes.

The Ministry of Culture and Equality is responsible for ensuring a good and diverse cultural provision throughout the nation. This requires access to suitable buildings and premises for the production, management and dissemination of culture. Through the National Cultural Buildings scheme, the Ministry of Culture and Equality provides grants to various types of cultural arenas based on applications from the cultural sector, with co-financing from other levels of the public administration. The Ministry also initiates the construction of cultural buildings via Statsbygg, fully financed by the state. When choosing such construction projects, sustainable, cost- and energy-efficient solutions are assessed as positive, preferably carried out by contractors with a focus on circular economy. The venues should contribute to cultural meeting places, where public participation is central.

Vålandstun assisted living facility , Stavanger. Client: Ineo Eiendom AS. Architect/Landscape architect: Haga & Grov AS/Smedsvig landskapsarkitekter AS. Photo: Sindre Ellingsen

Mellomlia 55–57 , Trondheim. Developer: Koteng Jenssen AS. Architect/Landscape architect: Arkitektkontoret Odd Thommessen AS/Agraff Arkitektur AS. Photo: Stine Østby

Lynghaugparken , Bergen. Client: Bergen municipality. Landscape architect: Norconsult AS and Curve Studio AS. Photo: Stine Østby

Skilpaddeparken , Mortensrud, Oslo. Client: Oslo municipality, the Agency for Urban Environment. Landscape architect: PIR2 AS and Bar Bakke AS. Photo: Fovea Studio

Kunstsilo , Kristiansand. Client: Kunstsilo Foundation. Architects: Mestres Wåge Arkitekter AS/Mendoza Partida Architectural Studio/BAX studio. Photo: Alan Williams

The Livestock Production Research Centre , NMBU Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ås. Client: Statsbygg. Architect/Landscape architect: Fabel Arkitekter AS. Title of artwork: Doxa. Artist: Gunvor Nervold Antonsen. Photo: Øystein Thorvaldsen

Cultural environment as a resource

Much of the architecture that is varied, considered, beautiful and enduring can be found in our historic built environments. Cultural environments often have aesthetic and spatial experiential values that create good surroundings in which to live. Some cultural environments contain high quality architectural expression and materials, while others may appear more worn and marked by time, yet still have great potential for reuse. What they have in common is that they contribute historical depth and distinctiveness that adds variety to towns and cities, strengthening a sense of belonging. Maintaining, restoring and reusing older buildings is circular economy in practice. We need to view existing buildings as a resource for the future.

Important parts of the nation’s history are linked to the design of towns and cities and the reason they are situated where they are. They bear traces of history – both archaeological remains and structures – in street patterns, urban plans and property structures, buildings and built environments, landscapes, parks and gardens. This is precisely what gives towns and cities the distinctive character that foster a sense of belonging. The Directorate for Cultural Heritage’s strategy and recommendations for urban development 37 has eight goals, including using cultural environments as a resource in sustainable urban development and preserving and continuing the diversity and cultural-historical distinctiveness when new projects are initiated.

County authorities, the Sami Parliament and municipalities play a key role in safeguarding a diversity of cultural environments through social and land-use planning. For municipalities to be able to take into account and utilise cultural environments as a resource in local development, it is essential they obtain a good overview of cultural environments within their municipality. Good plans ensures that municipalities achieve more knowledge-based and predictable land use. This provides clear and reliable frameworks for developers when they plan physical developments and densification within important cultural environments. The Government expects important cultural environments and landscapes to be mapped and protected in the planning process. 38

The Directorate for Cultural Heritage is preparing an overview of cultural environments and landscapes of national interest and has a number of examples of reuse and urban development. It is an important knowledge base that private and public sector actors can utilise for land-use planning and social development. In addition, the Ministry of Climate and Environment facilitates investment in cultural environments in municipalities (KIK). The goal is to heighten the competence of municipalities, allowing them to gain a better overview of cultural environments worthy of preservation and enabling them to protect them.

There are also a number of relevant financial incentives for protecting cultural environments. The Directorate for Cultural Heritage and the Cultural Heritage Fund have grant schemes for cultural environments in private ownership, and the Directorate’s value creation work provides funding to highlight cultural environments as a resource for social planning and development. Bygg og bevar (Build and preserve) has a website with an overview of various national and regional grant schemes, as well as grants from private foundations and funds.

Rødbankkvartalet , Tromsø. Developer: Sparebank 1 Nord-Norge and Rødbankkvartalet AS. Architect: NIELSTORP+ architects AS. Photo: Trygve Espejord

Tukthuset , Trondheim. Developer: Godhavn AS/private. Architect: Arkitekturfabrikken AS/Eggen arkitekter AS. Photo: Stine Østby

Northern Norwegian Art Museum , Bodø. Client: SNN-bygget AS. Architect/Landscape architect: Norconsult AS. Photo: Ernst Furuhatt

Vervet, Verftsparken and Slipptorget , Tromsø. Developer: Vervet AS. Architect/Landscape architect: LPO arkitekter AS/Lo:Le landskap AS. Photo: Marianne Koppinenen

Mellomlia 55–57 , Trondheim. Developer: Koteng Jenssen AS. Architect/Landscape architect: Arkitektkontoret Odd Thommessen AS/Agraff Arkitektur AS. Photo: Stine Østby

Public participation and dissemination

Planning and constructing our built environment is a collective endeavour that involves and impacts many people. Public participation is essential for garnering local knowledge and viewpoints on the choice of planning solutions and priorities. Involvement can help foster a sense of ownership, belonging and long-term user-friendliness – and reduce the risk of conflicts and ill-advised investments. Good architecture isn’t just about form, but also about creating places that function for the people who will use them. Architects, landscape architects, planners and representatives of other professions who participate in planning and design have an important role to play in raising awareness and understanding of the value of good architectural quality for users, neighbourhoods and society.

To strengthen the work of municipalities and private actors, the Government has developed a guide to urban development and architecture at planlegging.no. The Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development has also supported the National Association of Norwegian Architects’ (NAL) project to increase the number of architects in the public sector and improve architectural expertise in small and medium-sized municipalities, and supports the Bylivssenteret’s (urban life centre) work in offering guidance to municipalities on architecture and urban development. The Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development is collaborating with the Forum for Education in Social Planning (FUS), an association of 16 educational institutions including all the schools of architecture in Norway, to highlight the opportunities of choosing an education in planning.

The government agency Kulturtanken manages state funding for The Cultural Schoolbag scheme, which aims to ensure that all children and young people can experience a variety of high-quality artistic and cultural expressions, presented by professional artists and performers. This also includes the presentation of architecture, usually in projects related to cultural heritage and visual art. Experiencing architectural projects provides children and young people with knowledge about the built environment and helps strengthen their capacity for think critically, understanding of quality and aesthetic awareness.

In order to share experiences and build competence in the intersection between art and urban planning and development, KORO has, over the past four years, established a network for municipalities wishing to work with art in connection with urban development. Art placed in an architectural context and linked to urban development can contribute to social sustainability, attractiveness and a greater use of public spaces.

OBOS Living Lab , Oslo. Developer: OBOS Nye Hjem AS. Architect/interior architect: Lillestrøm Arkitekter AS, LPO Arkitekter AS/Metropolis interiørarkitekter AS. Photo: Jan Khür

K.U.K – Kjøpmannsgata Ung Kunst , Trondheim. Developer: Kjøpmannsgata Ung Kunst AS/Kjell Erik Killi-Olsen. Architect: HUS arkitekter AS/KEY arkitekter AS. Photo: Stine Østby

Ski station , Follo Linen, Nordre Follo. Client: Bane NOR SF. Architect/Landscape architect: LPO Arkitekter AS/ LINK arkitektur. Title of artwork: Through Landscape. Artist: Tiril Schrøder. Photo: Christian Tunge

Enduring qualities

The Government’s ambition is for towns, cities and neighbourhoods be built with a one-hundred-year perspective, within responsible financial frameworks for both developers and residents. As a society, we cannot afford to build with poor quality. Durable materials and construction methods, flexible solutions and good aesthetic design help promote a long lifespan. Architectural quality ensures that areas and buildings remain attractive and functional for future generations.

Gamle Sandnes town hall , Sandnes. Developer: Sandnes offentlige helsehus AS. Architect: Alexandria Algard architects AS. Photo: Mikael Olsson

Responsible investments

Much of the architecture that will surround us in the future already exists. There is great value in preserving what we have already built. At the same time, what we build today will form the architectural framework for people’s daily lives for decades to come. Everyone who plans and builds new architecture therefore has an important social responsibility. Enduring quality in the built environment also increases the value of the investments made – for property owners, individuals and society.

State property management must preserve value and be sustainable and efficient. The state owns a number of cultural-historical properties, with the defence sector holding the country’s largest portfolio. State properties vary in character, but one thing they share in common is that they represent part of the state’s history and development, and are markers in their cultural environments. Some of the properties have a long history and serve as examples of how long-term management can maintain values and qualities. When the state builds, it is important to plan with a long time horizon. This means designing buildings that can be adapted to new uses and, where possible, so that materials and building components can be reused. A prerequisite for the state’s building stock to endure far into the future is adapting them to a changing climate.

Time and costs in the defence sector’s property, building and installation projects are essential elements in ensuring the Norwegian Defence Pledge is implemented in line with ambitions. Going forwards, standard solutions will be developed for the design of barracks, quarters and housing in the sector. The goal is to shorten planning times and improve cost control with more predictability in terms of what is to be built and at what cost.

Tighter financial conditions are expected for the public sector in the coming years. The Government is committed to finding solutions that maximise the value of investments, and that everything built is planned in a way that maximises societal benefits. The public sector manages and invests in buildings, outdoor spaces and installations for health and care services, education, culture and sport, transport and energy. When the economy limits the scope of what can be built, it becomes even more important to transform and reuse existing buildings and infrastructure whenever possible, and to build at an appropriate size and invest in enduring qualities when new construction is necessary. Good architectural solutions can help ensure new buildings, outdoor spaces and installations are designed with the flexibility to accommodate changes in needs and use, thereby increasing their lifespans.

When executed with quality, good planning and architecture can ensure that investments in one sector save money in other sector budgets. This increases the added value of investments. The Government, for example, expects municipalities view the development of health and care services in conjunction with housing planning and the municipality’s long-term finances. 39 The right location, efficient land use and architectural solutions that facilitate the joint and co-use of space and functions can help reduce investment costs, save time and transport costs for users and staff, while also increasing utility value for service users.

The Government has amended the rules on public procurement, placing greater emphasis on environmental and social sustainability. In May 2025, the Government presented a proposition to the Storting (the Norwegian Parliament) concerning changes to the Procurement Act. 40 In this, the Government proposes that social considerations in public procurement be coordinated and consolidated into law.

Campus Kronstad , Bergen. Client: Statsbygg. Architect/Landscape architect: HLM arkitektur/Cubo arkitekter Danmark/Asplan Viak first stage of construction – L2 Arkitekter AS/Asplan Viak second stage of construction. Photo: Stine Østby

Dronning Ingrids hage , dementia village, Oslo. Client: Omsorgsbygg. Architect/Landscape architect: Arkitema K/S/White arkitekter AS. Photo: Nils Petter Dale

The right choices in early phases

The Government is committed to ensuring that public spaces and housing are built to a high quality, without increasing construction costs. The quality of the built environment is affected by decisions made in many different phases – from initial concept through to planning, design and construction, and throughout the building’s lifespan and use over many decades. Decisions made in the early phases related to choice of concept and location can have a major impact on architectural quality. The scope for exploring new solutions is greatest in the early phases, while the economic consequences of making changes increase as the process progresses.

The majority of construction projects are initiated, financed and implemented by private actors. Construction is expensive and the industry is vulnerable to economic fluctuations. The considerably high risk is a contributory factor to profitability being a key driver in development.

As planning authorities, municipalities play a key role in safeguarding architectural quality through their social and land-use planning. To ensure effective planning processes, municipalities should have updated plans with clearly defined expectations at a strategic level. The Government expects that municipalities use architecture as a tool in social development and define local ambitions for architecture and building design. 41 This helps provide predictability and creates scope for developers, in dialogue with the municipalities, to ensure quality in their projects through zoning-plan and building-application processes.

The Regulations on Technical Requirements for Construction Works set national minimum requirements for the qualities a building must have in order to be legally constructed. The regulations apply to new buildings and certain works on existing buildings. They are to ensure that building projects are planned, designed and executed with regard for safety, the environment, health, universal design and aesthetic qualities. Building regulations do not set in motion building projects but set the framework for the work the developer or homeowner wants to carry out. The regulations are mainly function-based, meaning they do not set requirements for specific solutions. This allows room for flexibility, innovation and development.

The Government is committed to reducing the time spent on planning and building application processes. In light of the goal of increased housing development, it is important to make processes simpler and more predictable for developers and municipalities. In spring 2025, the Minister for Local Government and Regional Development initiated a collaboration between the construction industry, municipalities and the ministry with the aim of launching measures to speed up planning and building application processes in order to help accelerate housing production. Work has been underway for several years to digitise building application processes, resulting in major cost savings for developers and municipalities. The Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development has recently proposed legislative changes that will contribute to faster, simpler and more predictable processing of building applications.

The Government’s proposed amendments to the Planning and Building Act concerning landowner financing of infrastructure 42 will make it easier, more predictable and faster to build housing in towns, cities and urban areas. When areas are transformed, new infrastructure is needed, such as green spaces, playgrounds, water and sewerage pipes, sports facilities, walking trails, streets and public transport hubs. These are important qualities for a good living environment. At the same time, old infrastructure may need to be removed. The bill provides municipalities with a new tool to ensure holistic planning and faster and more efficient implementation of these plans.

Haukeland University Hospital, Glasblokkene , Bergen. Client: Helse Bergen HF. Architect/Landscape architect: KHR Architecture, Rambøll AS/PKA Arkitekter AS/Schønherr AS. Title of artwork: Nice To See You. Artist group: Inges Idee. Photo: Pål Hoff

Guovdageainnu suohkan /Kautokeino school , Kautokeino. Client: Kautokeino municipality. Architect/Landscape architect: Holar Ola Roald AS/Lo:Le landskap AS. Photo: Rasmus Hjortshøj

Havegaten 1 , Tønsberg. Developer: Pilares Eiendom AS. Architect/Landscape architect: Holar Ola Roald AS/Landskapskollektivet AS. Photo: Landskapskollektivet AS

Lille Brønnøya Folkepark , Brønnøysund. Client: Brønnøy municipality. Landscape architect: Arkitektgruppen Cubus AS. Photo: Stephen Høgeli

Verket , Moss. Developer: Höegh Eigedom AS. Architect/Landscape architect: MEI/Lala Tøyen AS/A-lab AS/Mad AS/NIELSTORP+ arkitekter AS/Asplan Viak AS. Photo: Lala Tøyen AS

Wergelandsalleen 1 and 3 , Bergen. Developer: BOB. Architect: TAG arkitekter (now Sweco architects AS). Photo: Stine Østby

Need for knowledge and creativity

The complexity of what the built environment is expected to solve is increasing. Rapid change and new knowledge development create a need for increased efforts to achieve innovation in architecture, both in collaborative processes between public and private actors and in the solutions that are built. Statistics Norway’s innovation survey 43 shows there is potential for greater innovation in some of the industries that are key players in the development of the built environment.

Design and Architecture Norway (DOGA) promotes innovation and quality in the development of architecture and local development, with a particular focus on system understanding and user needs. Through various innovation and competence programmes, DOGA supports the early exploratory phase before services, products and built environments are designed. The goal is to reduce risk while increasing the added value of what is built.

Architectural professions are creative and proposal-orientated, providing physical solutions to challenges that need to be addressed. In 2024, the Government presented a roadmap for the creative industries. The roadmap highlights that the industry has untapped potential in Norway and points the way to growth and value creation. The goal is for creative industries to increase their profitability and contribute to inventive and innovative solutions. The roadmap emphasises that design and architecture are important industries in the green transition and can contribute both to solving societal challenges and creating added value for society. Furthermore, it emphasises that the public sector is an important commissioner of architecture and design services and has a key role in promoting innovative and sustainable solutions.

Creative industries such as architecture foster innovative collaboration, improve the understanding of needs, and enhance the cultural and social values of our physical environment, in interaction with technical, functional and economic considerations. Creative sectors like architecture also provide services that are in demand in other industries, such as the tourism industry, and are important for value creation in society. One of the initiatives that arose from the follow-up of the roadmap is the establishment of a public network to promote national knowledge sharing, coordination and collaboration among professionals working in the creative industries.

Architecture competitions can be used as a tool for generating new concepts and visions for urban development. Through competitions, interdisciplinary project teams can present new solutions to complex challenges. Competitions can also act as catalysts for public debate and awareness, inspiring both decision-makers and the public to discuss how we can shape the future.

OBOS Living Lab , Oslo. Developer: OBOS Nye Hjem AS. Architect/interior architect: Lillestrøm Arkitekter AS, LPO Arkitekter AS/Metropolis interiørarkitekter AS. Photo: Synne Dahl

Carpe Diem Dementia Village , Bærum. Client: Bærum municipality. Architect/Landscape architect: Nordic Office of Architecture/Bjørbekk & Lindheim landskapsarkitekter AS. Photo: Benjamin Ward

Gladengveien , Ensjø, Oslo. Client: Oslo municipality, the Agency for Urban Environment. Landscape architect: Bjørbekk & Lindheim landskapsarkitekter AS. Photo: Bjørbekk & Lindheim AS

Hasle Tre , Oslo. Client: Höegh Eiendom AS. Architect/Landscape architect/Interior architect: Oslo Tre AS/Grindaker AS/I-d. Interior Architecture & Design AS/Romlaboratoriet. Photo: Moritz Groba/Oslotre

Vollebekk torg , Oslo. Developer: OBOS Nye Hjem AS. Landscape architect: Studio Oslo landskapsarkitekter AS. Photo: Stine Østby