7 Coordinated spatial management and coexistence between ocean-based industries

Sound management of Norwegian seas and oceans provides predictability and a long-term perspective, and helps to avoid conflict between sectors in the future. The central government authorities are responsible for spatial planning and management in all areas beyond one nautical mile outside the baseline, on the basis of legislation for different sectors and the integrated ocean management plans.

The ocean management plans are intended to provide an overall balance between use and conservation, based on knowledge about ecological functions and the value and vulnerability of different areas together with information about economic activity now and forecasts for the future. Each management plan sets out a framework for petroleum activities in specific geographical areas, including areas where no petroleum activities will be permitted to safeguard environmental or fisheries interests, areas where there are restrictions on the times of year when exploration drilling is permitted, and other areas where there are environmental and fisheries-related conditions. The framework for petroleum activities is thus a form of spatial planning that takes special account of environmental value and fisheries interests. The framework for petroleum activities is implemented under existing petroleum-sector legislation, and more generally, activities in each management plan area are regulated on the basis of existing legislation governing different sectors.

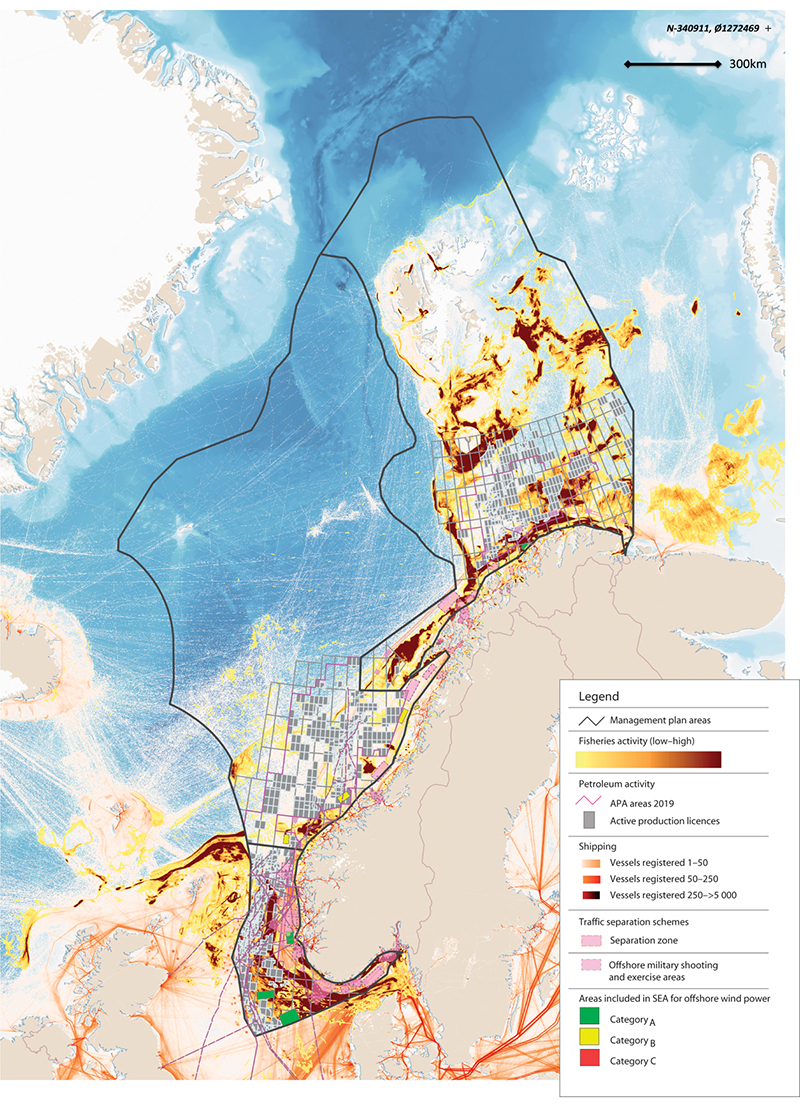

Earlier management plans include a thorough description of spatial overlap between three established ocean-based industries: fisheries, maritime transport and petroleum. In view of the expected growth in new and emerging ocean industries, the Government will consider whether there are certain geographical areas where many different interests intersect. It will be important to review the impacts, including the economic impacts, of various options for the use of Norway’s marine areas, and to consider where there may be spatial incompatibilities in individual cases.

Figure 7.1 Overview of commercial activity in the management plan areas.

Source Directorate of Fisheries, Norwegian Coastal Administration, Norwegian Environment Agency, Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Petroleum Directorate/Marine spatial management tool. Base map for the marine spatial management tool: GEBCO and Norwegian Mapping Authority

Marine spatial management tool

The North Sea–Skagerrak management plan (Meld. St. 37 (2012–2013)) identified the need to strengthen the spatial management element of the management plans and rationalise the process of updating and revising them. The Forum for Integrated Ocean Management was tasked with developing a tool for presenting and compiling spatial data for use in the management plan system, in close cooperation with BarentsWatch. The digital marine spatial management tool that has now been developed is designed to provide integrated geospatial information on industrial activities, species and habitats, and regulatory measures.

This will provide valuable support for sound spatial management in the management plan areas, and will be useful for the authorities, the business sector, interest organisations, other users of Norway’s waters and the general public.

The spatial management tool contains geospatial data sets for natural resources, commercial activities, environmental status, plans and regulatory measures, relevant reference data and basic marine data. The spatial management tool is still being developed as a support tool for work on the integrated ocean management plans. It is also a way of making the knowledge base for the management plans publicly available.

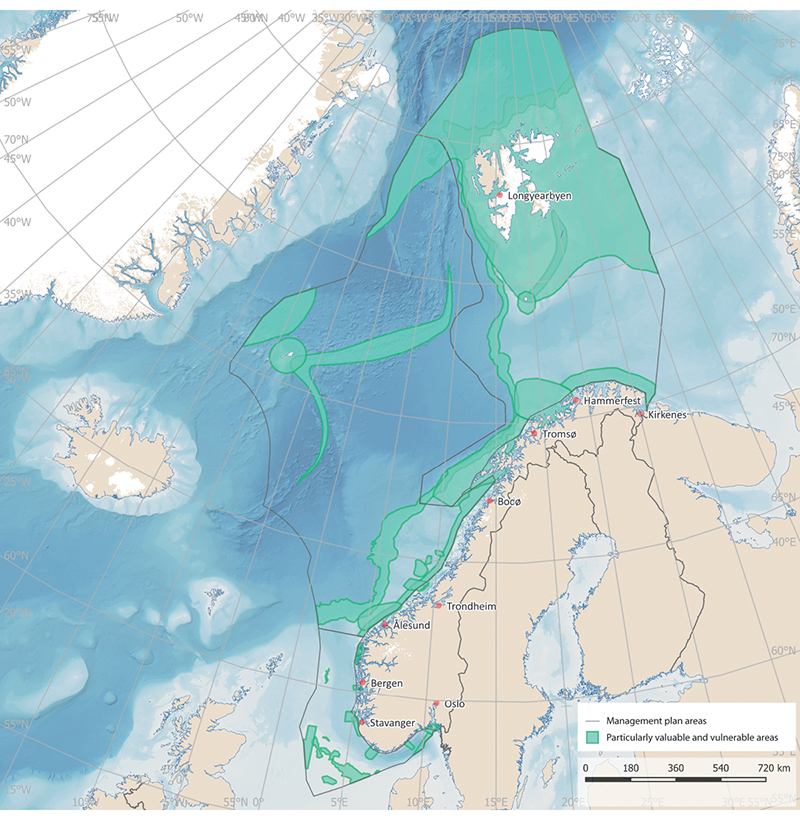

Figure 7.2 The particularly valuable and vulnerable areas identified in the three ocean management plans.

Source Norwegian Environment Agency/Marine spatial management tool

Particularly valuable and vulnerable areas

Particularly valuable and vulnerable areas have been identified as being of great importance for biodiversity and biological production in an entire management plan area. In these areas, activities will be conducted with special care and in such a way that the ecological functioning and biodiversity of the areas are not threatened. The designation of areas as particularly valuable and vulnerable does not have any direct effect in the form of restrictions on commercial activities, but indicates that these are areas where it is important to show special caution. It is possible to use current legislation to make activities in such areas subject to special requirements, and thus protect valuable species and habitats. The particularly valuable and vulnerable areas have been delimited on maps, and are further presented in Chapter 3.

7.1 Norway’s ocean management and its implications for regional growth and development

Spatial management of the waters closest to the coast (out to one nautical mile outside the baseline) is subject to the rules of the Planning and Building Act on planning and public consultation processes and environmental impact assessment. This means that there is a more fully developed system for coordination, cooperation and participation of all interested parties as regards spatial management in coastal waters. Legislation other than the Planning and Building Act also contains provisions that have implications for spatial management along the coast, including the Act relating to ports and navigable waters, the Marine Resources Act and the Aquaculture Act. Further out from the coast, spatial management is the responsibility of central government authorities.

Marine spatial planning and developments on land are closely linked. Decisions on where to site activities at sea may have major implications for developments at municipal and county level on land. At the same time, ocean-based commercial activities are dependent on infrastructure on land, including ports, transport networks and emergency preparedness and response resources.

The Government’s 2019 ocean strategy, Blue Opportunities, had a clear regional focus. Norway’s national ocean policy is developed through cooperation between central government, county and municipal authorities. A forum for systematic dialogue on ocean issues has therefore been established involving the Government, the counties, the Sámediggi (Sami parliament) and representatives of coastal municipalities. Other stakeholders are invited to take part when appropriate. The purpose of the forum is to facilitate dialogue, and it is not a decision-making body. The members of the forum decide on topics for discussion together, based on the priority areas of the ocean strategy that have implications for knowledge-based management, value creation, employment and skills in coastal communities.

7.2 Designating marine space for different uses – main features of decision-making processes

Authorities in different sectors are responsible for allocating decisions on which parts of marine space are to be allocated to different types of activities under the legislation they administer.

Offshore wind power

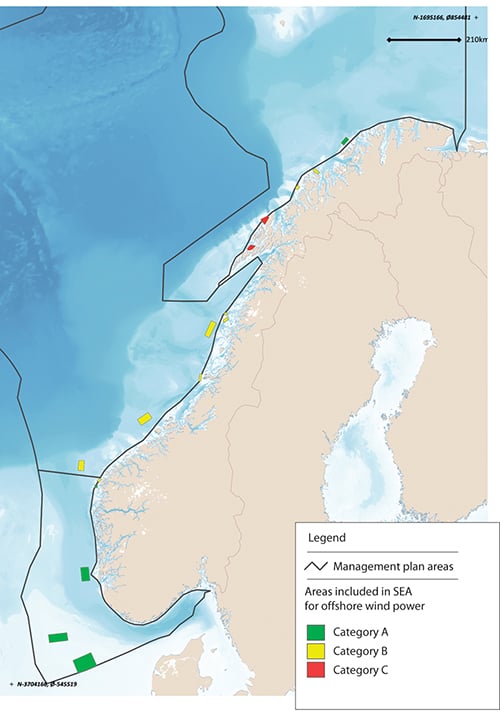

Apart from a floating wind turbine off Karmøy, there are no offshore wind farms in Norwegian waters. The Hywind Tampen wind farm, which will provide two oil fields with electricity, is being developed in the North Sea. So far, no areas have been opened for wind power development under the Offshore Energy Act. However, offshore wind power is showing strong growth internationally, especially in the North Sea.

In 2010, a working group led by the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate identified 15 areas it considered suitable for offshore wind power. In 2012, the Directorate conducted a strategic environmental assessment of the 15 areas to consider whether they should be opened for licence applications. This ranked the areas according to suitability, and recommended giving priority to five of them. The purpose of the strategic environmental assessment was to avoid conflict between wind power and other important interests, while also taking into consideration power grid access, development costs and the available wind resources. Nevertheless, it seems clear that offshore wind power could potentially come into conflict with other interests.

In 2019, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy carried out a consultation process on whether two areas, Sandskallen-Sørøya North and Utsira North in the North Sea, should be opened for offshore energy production, and on draft regulations including rules governing the licensing process.

Figure 7.3 Areas included in the strategic environmental assessment for offshore wind power.

Source Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate/Marine spatial management tool

Licence applications for offshore renewable energy production are dealt with under the Offshore Energy Act, which is the responsibility of the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. The process for the Hywind Tampen wind farm is being dealt with under the Petroleum Act, which is the responsibility of the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy.

Offshore aquaculture

There has been growing interest in the development of offshore aquaculture in recent years. This is explained by a need for more space and by environmental and disease problems in a number of areas used for aquaculture at present. If aquaculture facilities are sited further out from the coast, new conflicts of interest are likely to arise with the traditional fisheries, shipping and offshore wind farms.

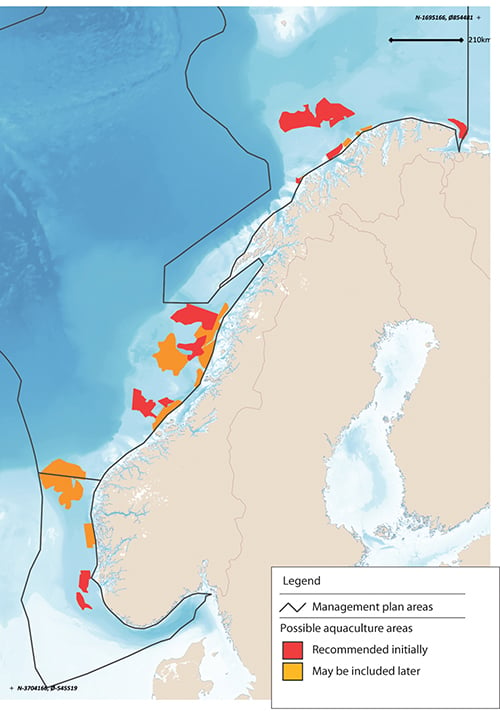

Figure 7.4 Areas recommended for inclusion in a strategic environmental assessment of offshore aquaculture.

Source Directorate of Fisheries

An interministerial working group has prepared a report on offshore aquaculture. This recommends that in areas outside the geographical scope of the Planning and Building Act, the central government should open sizeable areas (blocks) for offshore aquaculture under the Aquaculture Act. After this, it will be necessary to determine where the actual facilities are to be sited within each block. Further review of this process will be needed.

The report also recommends requiring the establishment of safety zones round offshore aquaculture facilities, and that these should be larger than the zones around coastal facilities. In addition, marking of aquaculture facilities should be adapted to operations in more open and exposed waters. Mobile self-propelled systems should be subject to the same navigational requirements as other shipping, to avoid collisions. More knowledge is needed about the migration routes, habitats and feeding grounds of important wild fish species so that environmental considerations can be properly incorporated.

The Directorate of Fisheries has recently submitted a proposal recommending strategic environmental assessment of 11 areas outside the geographical scope of the Planning and Building Act that have been identified as suitable for offshore aquaculture, and identifying 12 areas that may be included at a later date (Figure 7.4). Any allocation of areas will be decided under the Aquaculture Act, which is the responsibility of the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries.

Extraction of seabed minerals

Exploration for and exploitation of seabed minerals may in future become an important ocean industry for Norway.

The areas where minerals are likely to be extracted are expected to be far from the coast, in contrast to those that are attractive for many other activities.

The Seabed Mineral Act is administered by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, and is based partly on experience gained from petroleum activities. Under the Act, an area must as a general rule have been officially opened before licences can be issued for exploration and extraction.

Bioprospecting

Bioprospecting is a systematic search for organisms, genes and molecules that could provide key components for various products and processes in medicine, the process industries, food production and other sectors. As new sampling technology is developed, larger parts of the oceans will be of interest for bioprospecting.

Norway has no current plans to designate specific areas for bioprospecting, and areas where there are organisms that might be possible to exploit through bioprospecting in the future have not yet been systematically identified. Any regulation of the use of specific areas for bioprospecting would be introduced under the Marine Resources Act (Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries) or the Nature Diversity Act (Ministry of Climate and Environment).

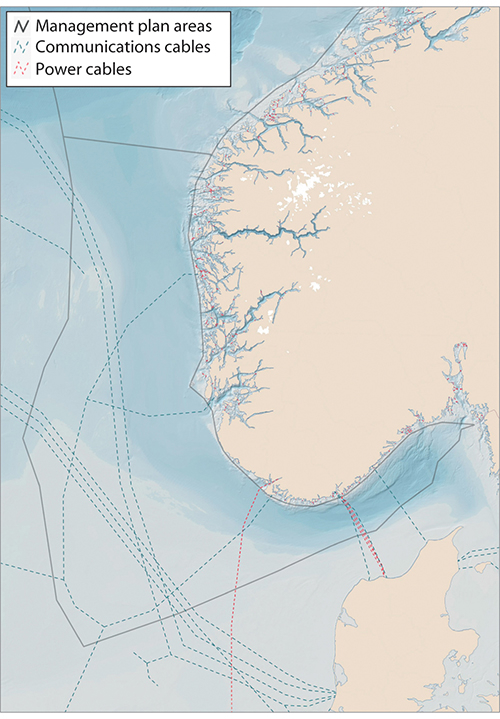

Routes for submarine cables

Submarine communications cables carry large volumes of data traffic. For example, almost all internet data traffic between islands and continents is transferred by cable. In Norwegian waters, the network of communications cables will grow and they will occupy larger areas of the seabed as the volume of data traffic rises.

There is currently no coordinated system determining where and when such cables are laid in Norway. Laying submarine communications cables is not regulated by law in the same way as other maritime infrastructure. The Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation has started legislative work on the regulation of submarine fibre-optic cables.

As a general rule, anyone planning to lay submarine power cables must apply for a permit under the Act relating to ports and navigable waters. Applications are processed by the Norwegian Coastal Administration. Information on such projects must be forwarded to the Norwegian Mapping Authority for inclusion on charts.

Norway has submarine power cables from the mainland to island communities, from the mainland to other countries (interconnectors), and from the mainland to certain petroleum installations. There are four subsea interconnectors between Kristiansand and Denmark, and one between Feda and the Netherlands. In addition, Statnett is building two new interconnectors, one between Feda and Germany and one between Kvilldal and the UK.

The oil and gas fields Valhall, Gjøa, Troll, Ormen lange, Snøhvit, Goliat and Johan Sverdrup are all now supplied with power from shore. Power from shore will also be used to supply the Martin Linge field when it comes on stream, and the joint solution for supplying power from shore to the Utsira High region will be in place by 2022. The petroleum industry is currently assessing whether to supply Oseberg, Troll B and C, Draugen and the fields on the Halten Bank with power from shore. Licensees are required to assess whether to use power from shore in connection with all new independent developments and major changes to fields that are on stream. In February 2020, the Norwegian oil and gas industry presented its climate roadmap, which includes an ambition to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the sector by 40 % by 2030 and to close to zero by 2050. Using power from shore will be an important way of achieving these targets.

Development of offshore wind power will also require the construction of associated infrastructure. Offshore wind farms will generally be connected to the electricity grid via production radials owned by the producers. Alternatively, they can be connected to petroleum installations. Offshore wind developments that are largely intended for power export could be connected via radials directly to another country’s grid.

Figure 7.5 Submarine communications and power cables.

Source Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate/Telegeography/EMODnet-Human Activities/Marine spatial management tool

Under the Energy Act, installations for production, transformation, transmission and distribution of electric energy inside the baseline may not be built, owned or operated without a licence. The Offshore Energy Act has similar licensing provisions for installations outside the baseline. However, the licensing provisions of the Offshore Energy Act may be set aside for electrical installations that are an integral part of petroleum activities and that are processed under the Petroleum Act.

The requirement to obtain a licence under the Energy Act also applies to new cables to link production facilities, interconnectors or petroleum installations to the grid in mainland Norway and to interconnectors between the Norwegian grid and other countries. For interconnectors, an additional licence for the export and import of electrical energy is required under the Energy Act, or under the Offshore Energy Act for interconnectors directly from installations on the Norwegian continental shelf to other countries.

The Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate is the licensing authority for electrical installations, except for new major power lines longer than 20 kilometres carrying a voltage of 300 kV or more, which are licensed by the King in Council. The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy is the licensing authority under the Offshore Energy Act.

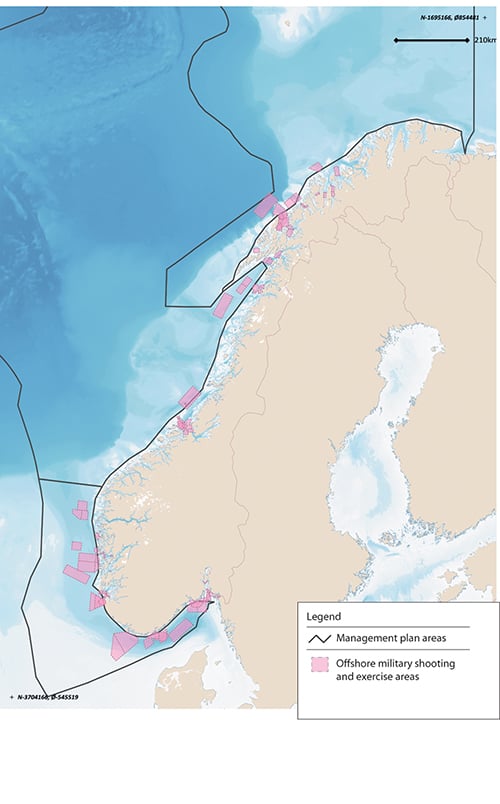

Offshore military shooting and exercise areas

The Norwegian Armed Forces currently have 87 offshore military shooting and exercise areas, from parts of the Oslofjord in the south to Kvænangen in the far north. These are described in an Official Norwegian Report (NOU 2004:27). Offshore shooting and exercise areas are essential to the Norwegian Armed Forces’ operational activities and ultimately for national emergency preparedness and crisis management capabilities. They are also intended to meet training and exercise needs for personnel, for testing equipment and for operational training for the Norwegian Armed Forces alone and together with allies. Areas have been designated to permit training for airborne, naval and underwater operations. When using these areas for exercises or other purposes, the Armed Forces must ensure that the environment is properly safeguarded.

Figure 7.6 Offshore military shooting and exercise areas for the Norwegian Armed Forces, 2000.

Source Norwegian Armed Forces/Marine spatial management tool

The Ministry of Defence has tasked the Norwegian Defence Estates Agency, in cooperation with the Norwegian Armed Forces, with reviewing offshore military shooting and exercise areas. All relevant planning authorities in different sectors are involved in the work. The purpose is to look at how to formalise and manage these areas. The project also includes a review of the structure of the shooting and exercise areas and possible adjustments in the light of future needs, and it will make recommendations for decommissioning or changing existing shooting and exercise areas and for establishing new areas. The project will also consider the possibility of sharing the use of such areas with civilian interests, and is to be completed by mid-2020.

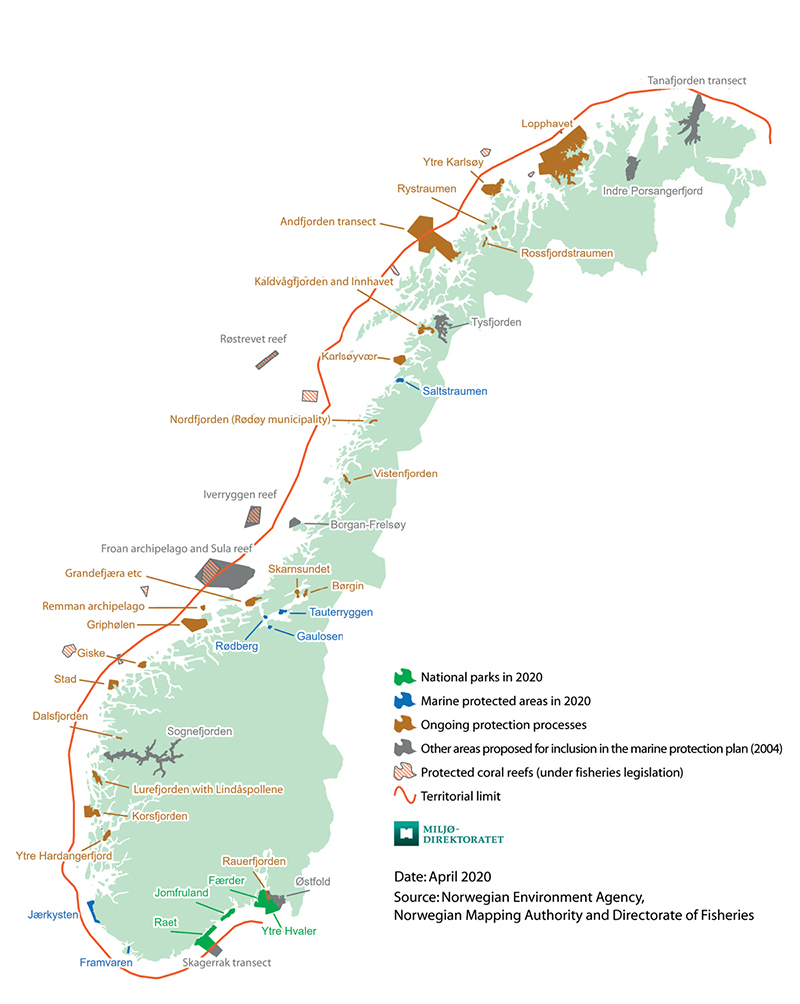

Marine protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures

Marine protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures are important tools for safeguarding areas where there are important ecosystems, habitats and species. The purpose of these tools is to ensure that areas are managed in a way that maintains their conservation value for the future. To achieve this, it must be possible to regulate pressures on conservation areas, and to implement active conservation measures where necessary. Any restrictions imposed on activity in such areas must be proportional to the purpose of protection.

Figure 7.7 Existing and planned marine protected areas around mainland Norway.

Source Norwegian Environment Agency, Norwegian Mapping Authority and Directorate of Fisheries

Marine protected areas under the Nature Diversity Act may be established in Norway’s territorial waters, which extend to 12 nautical miles beyond the baseline. Around Svalbard, important marine species and habitats are protected where they are included in the marine parts of the national parks and nature reserves established under the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act.

In addition to the areas that are protected under these two Acts, marine protected areas can be established under the Marine Resources Act in all Norwegian waters and on the Norwegian continental shelf.

Efforts to safeguard marine areas and their species and habitat diversity for the future have been in progress for many years. In 2004, a broad-based advisory committee identified 36 marine areas along the coast that for further evaluation as part of these efforts. As of April 2020, six marine protected areas and four national parks including substantial marine areas had been established under the environmental legislation, and a further 18 marine protected areas including coral reefs had been established under the Marine Resources Act. Work on marine protected areas was discussed in more detail in the white paper Nature for life: Norway’s national biodiversity action plan (Meld. St. 14 (2015–2016)) and the 2017 update of the Norwegian Sea management plan (Meld. St. 35 (2016–2017)). Work on an overall national plan for marine protected areas has been started. A review of relevant area-based conservation measures has also been started so that appropriate fisheries management measures can be included when Norway reports to the Convention on Biological Diversity and other international forums on the proportion of marine and coastal areas covered by conservation measures.

Tourism

The tourism sector in Norway has been growing steadily for the past 10 years. Few countries have as long and varied a coastline as Norway, and the coastal environment, fjords and marine areas have great potential in terms of tourism.

No areas of sea are set aside specifically for tourism activities, as is done for several of the other ocean-based industries. However, certain restrictions have recently been introduced to avoid conflicts with fishing operations. It is now prohibited for whale-watching vessels to sail closer than 370 m to fishing vessels or fixed fishing gear, or for people swimming, diving or canoeing/kayaking to approach closer than 750 m. These restrictions have been introduced under the Marine Resources Act (Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries).

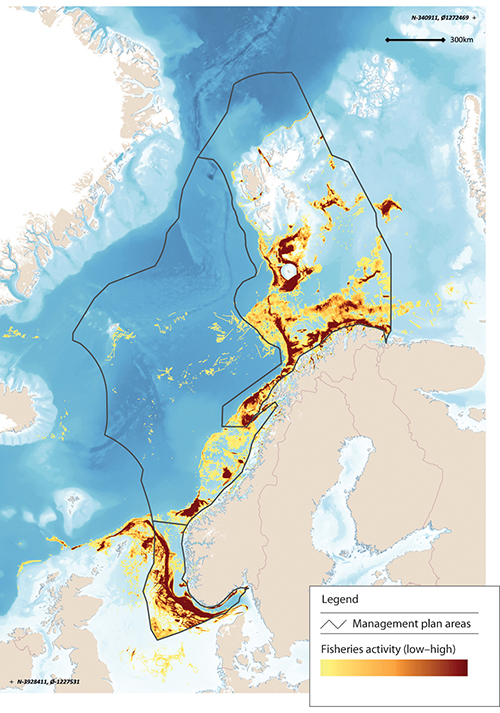

Figure 7.8 Level of fisheries activity in Norwegian waters.

Source Directorate of Fisheries/Marine spatial management tool

Fisheries

The level of fisheries activity varies over the year, from year to year, depending on stock development and changes in distribution and migration patterns (see Figure 7.8). Fishing grounds are not clearly delimited areas. Regulatory measures and spatial needs vary from one type of fishing gear to another. The distribution of some species, for example herring, is highly dynamic. In addition, changes are being observed in the distribution and migration patterns of many fish species as a result of climate change.

Currents along the Norwegian coast often form eddies rich in plankton and nutrients in the shallow bank areas. The availability of food and good light conditions result in high densities of fish locally in these waters. In addition, bottom conditions are favourable for the use of fishing gear, and the bank areas are therefore important fishing grounds.

The use of marine space by the fisheries is regulated under the Marine Resources Act (Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries).

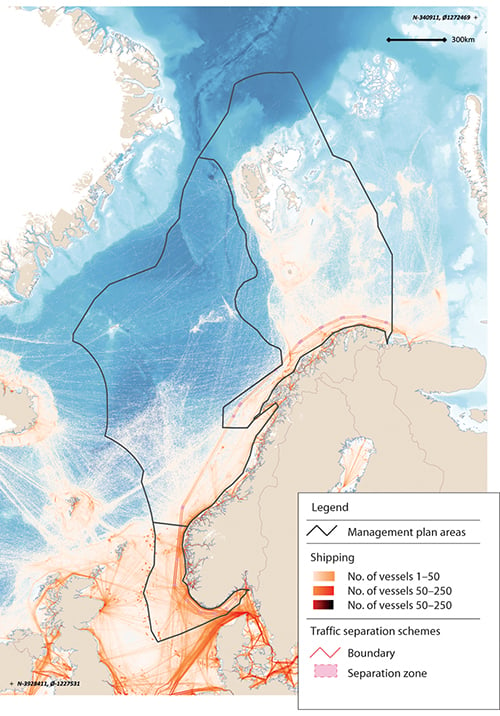

Figure 7.9 Map of shipping density.

Source Norwegian Coastal Administration/Marine spatial management tool

Maritime transport

Maritime transport accounts for more than 70 % of transport work in areas under Norwegian jurisdiction and 90 % of the volume of international transport. Maritime transport is thus very important both for the Norwegian business sector and for foreign trade. The volume of shipping (expressed as distance sailed) is expected to rise by about 40 % by 2040.

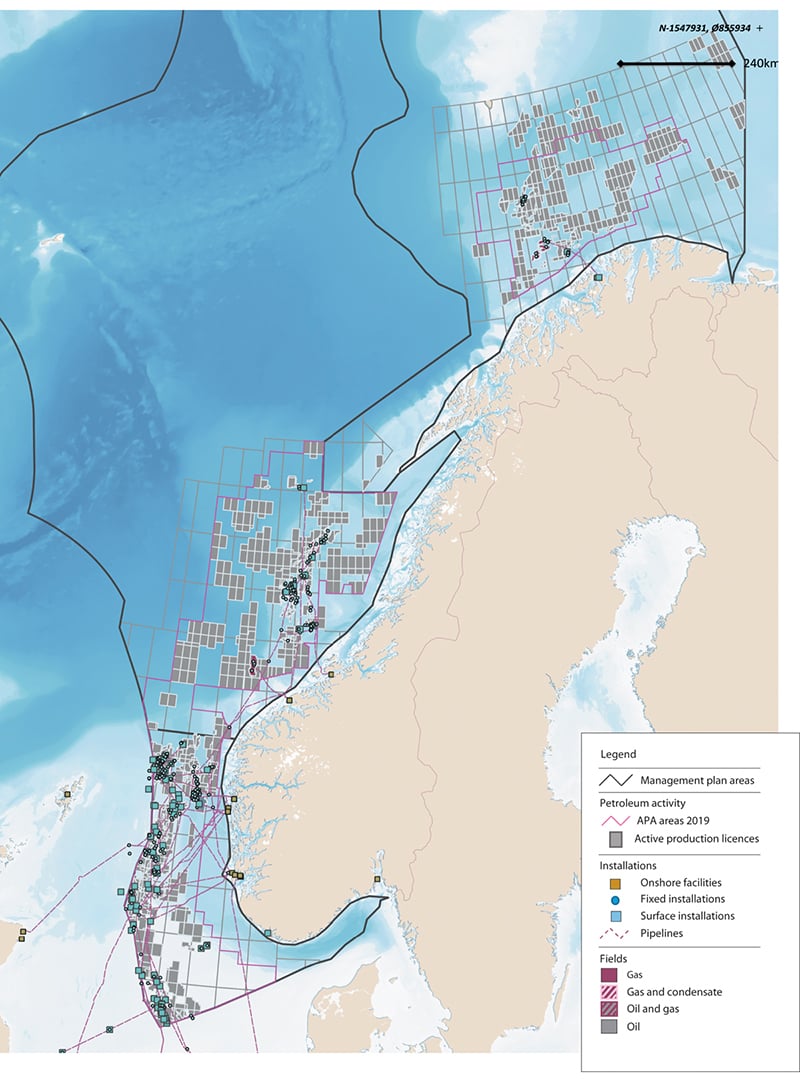

Figure 7.10 Petroleum activity on the Norwegian continental shelf.

Source Norwegian Petroleum Directorate/Marine spatial management tool

Areas are designated for traffic separation schemes, recommended routes and other regulatory measures for fairways under the Act relating to ports and navigable waters. Traffic separation schemes and recommended routes in Norway’s exclusive economic zone must also be approved by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The introduction of traffic separation schemes and recommended routes along the coast has helped to move shipping further out from the coast, separate traffic streams in opposite directions and establish a fixed sailing pattern (Figure 7.9). This reduces the likelihood of collisions and groundings and makes it easier to intervene in the event of an accident.

In some cases, it might be possible to move recommended routes in the interests of other activities, but this is a process that requires extensive risk assessments and IMO’s approval. In other cases, this would not be possible, because moving a route would have negative impacts on maritime safety or would seriously impede passage in the area. Moving recommended routes further away from the coast could increase the distance sailed, increase greenhouse gas emissions and make it more complicated to provide assistance to ships when necessary.

Petroleum activities

Petroleum activities may take place in areas opened by the Storting (Norwegian parliament) under the conditions set out in the ocean management plans.

Acreage for petroleum activities is allocated through two equally important types of licensing rounds. New acreage in frontier areas is allocated in numbered licensing rounds, which are normally held every other year. In more mature areas, where more is known about the geology and that are closer to planned or existing production and transport infrastructure, licences are issued every year through the system of awards in predefined areas (APA). The licensing process involves a number of steps. Numbered licensing rounds are opened by inviting companies to nominate blocks. The authorities assess the nominations, and a proposed announcement is submitted for public consultation. After this, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy announces the round. After the applications have been processed and after negotiations with the companies on licensing conditions, the government makes the final decision on which areas are to be covered by production licences and the mandatory work programme for each licence. More details can be found in Chapter 5.

Petroleum infrastructure, including platforms, subsea installations, pipelines and safety zones around installations, occupies large areas. At the beginning of 2020, 87 fields on the Norwegian continental shelf were producing oil and gas: 66 in the North Sea, 19 in the Norwegian Sea and two in the Barents Sea. The total length of gas pipelines installed on the Norwegian continental shelf is 8 800 km.

In addition to the permanent installations, seismic surveys occupy considerable areas while they are in progress. Seismic surveys are carried out at all stages from exploration to final production. Even though seismic surveys only last for a relatively short time in each phase, this is the activity that leads to the greatest conflict with the fisheries. Delaying seismic surveys can be extremely costly for the petroleum industry.

Petroleum activities are licensed under the Petroleum Act (Ministry of Petroleum and Energy).

7.3 Coordinated marine spatial planning in other countries

About 70 of the member states of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (UNESCO-IOC) now have some form of marine spatial planning. Norway’s ocean management plans are considered to constitute an established marine spatial planning system. Different countries’ systems vary widely. In 2014, the EU adopted a directive establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning (2014/89/EU, MSP Directive). The expected benefits of maritime spatial planning are:

It will reduce conflicts between sectors and creates synergies between different activities.

It will encourage investment by creating predictability, transparency and clearer rules.

It will increase cooperation between countries to develop energy infrastructure, shipping lanes, pipelines, submarine cables and other activities, and also to develop coherent networks of protected areas.

It will protect the environment through early identification of impacts and opportunities for multiple use of space.

Under the MSP Directive, the 23 coastal states of the EU are required to establish national maritime spatial plans by 31 March 2021. Member states themselves are responsible for determining the content of their plans and finding a balance between the use of the maritime space by different sectors. However, their plans must include all activities at sea, and these must be considered in conjunction with land-based activities. The plans must also facilitate cooperation between authorities in different sectors and different sectoral interests, and with third countries that have jurisdiction over adjoining coastal and marine areas. The MSP Directive has not been incorporated into the EEA Agreement.

Together with the EU Commission, the IOC has initiated a global project to promote marine spatial planning as a tool for implementing Sustainable Development Goal 14 on life below water and the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development.