Part 1

Ownership – significance for value creation

2 Ownership – significance and development trends

This chapter describes the significance that ownership may have for value creation. It gives a portrayal of what characterises good owners and of key development trends in the exercise of ownership in recent years. The topics described relate primarily to commercial companies, but will be transferable to some extent to other types of companies.

2.1 The significance of ownership for value creation

Ownership can be highly significant for value creation. Different phases of a company’s development present different needs, and different owners may have varying preconditions for contributing to a company’s development. These relate to, for instance, expertise, controllability, objectives, access to networks, preconditions for contributing to restructuring and innovation, and for contributing capital on the basis of risk appetite and capacity. What constitutes a good combination of company and owners may vary with the company’s phase of development, growth and nature. A diversity of owners, owner types and owner communities will contribute positively to a good combination of company and owners, sound business development and economic value creation over time.

An increased rate of change in business and industry means that the importance of the company’s ability to adapt and innovate increases. This places greater demands on the owners, who set policies for the companies’ activities, and make critical decisions in the event of major changes in the companies. This may, for example, relate to the setting up of new businesses and to the acquisition, divestment and winding up of businesses. In such a business climate, competent owners with the ability to understand a company’s situation, challenges and opportunities are important for realising the company’s potential for value creation.

The owner can contribute to the companies’ value creation in a number of ways. These are described in more detail below.

2.1.1 The importance of capital allocation

Well-developed and competent owner communities are a prerequisite for value creation. Owners and investors have a fundamental role in facilitating profitable business activity by contributing risk capital for the establishment of new companies or for expanding established companies.

In the capital market, those who want to save are connected with those who want to lend and invest. In this way, capital is channelled to potentially profitable investments, and risk is distributed between the participants. In this fashion, the capital market streamlines the use of resources in the economy.

Sound decisions concerning financing are contingent on sufficient knowledge about expected profitability, risk, markets, sectors, companies and the position the company is in. Strong and competent owner communities and professional communities can be crucial for analysing and understanding risk and potential returns, and thereby ensuring the appropriate capital input.

2.1.2 The importance of the exercise of ownership

Ownership is important for how companies are governed and run. Owners can be involved in companies in different ways and to different extents, depending on the ownership model. At one extreme are financial owners who allocate capital through small shareholdings, and who are easily able to liquidate positions if the company does not perform and deliver returns as expected. At the other extreme are owners who get involved in companies’ operations and aim to develop profitability over time and exploit inter-company synergies.

Good owners with a low level of active involvement will primarily ensure that companies follow principles of good corporate governance and commercial management in order to protect their own interests. With a greater degree of involvement, owners may try to create added value by supporting and following up the companies. Such owners may, for example, use networks and their own industrial expertise in order to complement the executive management, and also influence who is on the board and thereby also on the management. They are more prone to impose requirements on the board and management based on their own knowledge of relevant markets and sectors, and may become involved in companies’ strategy formulation or giving direct operational support.

Private equity (PE) investors are an example of owners who have extensive involvement in the companies in their portfolios. These owners receive a lot of attention but they constitute a relatively small part of the overall ownership community.

The model for PE investors is to take over companies where they can realise a potential for running the company better or contributing to further growth. PE investors are also liable to make changes to management and/or provide direct operational support. In many cases, they contribute to both organic growth and growth through acquisition. Analyses indicate that returns on PE funds have been higher than for the rest of the market, including when adjusted for the gearing ratio. Since 1995, US PE funds have yielded returns three percentage points higher on average than the S&P 5001. There have typically been large differences in funds which perform well and those which perform badly, with traditionally great stability in respect of which participants perform well. This indicates that skill in exercising ownership creates value. The figures for recent years also indicate that the PE investors as a whole have gradually become more professional, that there is now less difference in performance between the participants, and somewhat lower stability as to which investors perform well over time. What creates high returns for the PE investors has changed over time. Formerly, the return was largely based on identifying and investing in the right companies and sectors («buying well»). In recent years, the trend is towards good ownership being increasingly taken to mean driving value creation («owning well»)2. This may reflect the fact that the owners’ expertise has become more significant.

The owners choose the company’s board. A competent board is important if a company is to be operated prudently and profitably. Some owners sit on the board themselves, and through their board representation participate directly in the company’s administration. Some owners also participate in the executive management in various ways.

The owners’ primary aim will essentially be to maximise the return on invested capital at the desired level of risk. The company management may have incentives for pursuing other objectives. This is normally referred to as the principal-agent problem3. The relationship between the majority and minority shareholders, between management and employees, and between management and other stakeholders are other key agency dilemmas in the corporate context. The diminution of potential difficulties in such relationships is key to various principles for sound corporate governance, such as those of the OECD4. Such difficulties do not necessarily reduce value creation, but they may affect the risk and also redistribute the return between stakeholders. Conflicts of interest between the owners, where one or more owners attempt to enrich themselves at the cost of others, may however tend to reduce the total value creation in the company by wasting resources. The owner is often not able to observe or control the management’s activities directly. The owners can also lack knowledge as to what the best operational decisions will be. Accordingly, the management often has an information advantage that they can use to pursue their own objectives, in preference to the owners’ desire for the highest possible return on invested capital over time.

There is a comprehensive literature on the effect of good corporate governance on company value creation, but due to the complexity of the subject, conceptual ambiguities and regional differences, it is difficult to point to unambiguous results. There does however appear to be a broad sense that good corporate governance is important for value creation, and the literature is tending to provide empirical support for this view5.

2.1.3 Owner composition and owner types

The owner composition and owner types may be significant for value creation in companies by creating different incentives for exercising good corporate governance. Accordingly, different combinations of owner concentration, owner type and duration of ownership may influence the quality of the exercise of ownership6.

The benefit of a high concentration of ownership is that large owners are likely to be better placed to assert their interests towards management than owners in a more fragmented shareholder structure. A high concentration of ownership can therefore reduce the agency costs. Conversely, a high concentration of ownership can make it more difficult for the minority shareholders to assert their interests. Furthermore, a high concentration of ownership will reduce liquidity in the shares. Liquidity is an important factor for investors, since a high liquidity lowers the cost of exiting a company. In addition, low liquidity provides poorer pricing data. Good pricing data can help discipline company management and reduce agency costs, especially in the case of a fragmented ownership structure or other circumstances where the owners have little direct control over the management. For example, the FTSE 100 index7 operates with a minimum requirement of 25 per cent free float8, and it has been discussed increasing this further. On the Oslo Stock Exchange, profitability of companies with high concentration of ownership appears to be lower than for companies with low concentrations of ownership, whereas the relationship is more inconsistent internationally6.

A key distinction between owner types is between indirect and direct owners. Indirect ownership means that the ownership is administered through a third party, for example, a fund. Indirect ownership is therefore at two removes of agency from management instead of one. Institutional ownership can have positive effects in that, as a rule, an institution will be larger and possess more expertise than private individuals. On the other hand, direct owners, who administer their ownership themselves, have greater incentives for managing their ownership well.

Another distinction between owner types is between public and private sector. The literature provides no clear answer as to whether private ownership provides a better return than public ownership, but some research does support this perception9. The mechanisms behind this potential phenomenon are unclear, but one possible explanatory parameter may be that the public sector is an indirect owner10. Furthermore, a high public sector concentration of ownership in individual companies (which is often the case) may have an effect by reducing liquidity, which in turn may affect market prices. It is important to note that the conclusions will depend on factors such as which market the research was done in and when.

The duration of the ownership will have consequences for its exercise. Long-term owners can create value by financing strategies that produce long-term, but not necessarily short-term, gains. On the other hand, long-term ownership can lead to less pressure on the management. Research performed on Norwegian stock exchange data gives some indication that indirect long-term ownership yields lower returns, while direct long-term ownership yields higher returns. In listed companies, investors are typically divided into traders, mechanical investors and value investors, according to how they allocate capital. Traders attempt to achieve a return by picking the right time to move in and out of shares. Mechanical investors follow indexes and place capital passively in order to achieve the market return. Value investors are investors who seek to place their money in companies which they believe, over time, will produce a return due to the company’s fundamental value. How the shareholder structure is defined by the different shareholder categories may be significant for the company’s valuation, its liquidity and volatility, and may therefore affect the return.

2.2 What characterises good owners?

Value creation ensuing from capital allocation and corporate governance will vary between the different types of ownership models. The distinction here is between owners who primarily perform capital allocation, long-term strategic investors and owners with operational involvement; see figure 2.1. The following expands briefly on what characterises the main owners within each model.

Figure 2.1 Three models of ownership.

2.2.1 Owners focused on capital allocation

These are owners who primarily maintain a diversified portfolio, with small shareholdings in each company. They typically have investments of small shareholdings in 100–5,000 companies. The value-creation logic is centred around dynamic portfolio adjustments, with little involvement in the companies invested in. In order to ensure good diversification, the portfolio may well be spread over different geographical areas and different asset classes.

These owners create added value by performing capital allocation based on profound expertise and insight into financial and capital markets. The ownership is exercised by having clear criteria and guidelines for the requirements they have of the companies they invest in. Voting rights at general meetings are used actively in order to promote good corporate governance. These owners are often adept at working with other shareholders to achieve desired changes. If the companies they invest in prove not to meet the defined criteria or do not perform as expected, the shareholdings will be sold («voting with their feet»). In recent years, especially as a result of the financial crisis, «tactical investments» have increased in scope. These are investments which try to evaluate market timing more actively and achieve a return on short-term investments.

2.2.2 Long-term strategic owners

These are owners who attempt to create value by adopting long-term strategic positions, and who support the portfolio companies’ management and value creation. The typical long-term strategic investor usually has between 10 and 50 companies in the portfolio, and shareholdings between 10 and 100 per cent. The shareholding must be large enough for the investor to have direct influence in the companies, for example through board representation, so that it is possible to create added value by taking part in defining the individual company’s direction.

With their profound knowledge of the industry and extensive familiarity with the individual companies, these owners seek to help improve long-term returns from the portfolio. This requires an independent sense of companies’ strategies and business models. Good long-term strategic investors work proactively to influence key strategic decisions. These owners will typically be represented on the boards of the companies on the portfolio. As part of their strategy follow-up, good owners will participate in promoting major strategic initiatives in the portfolio companies and will also provide support for strategy execution. The owners will typically set clear financial and strategic objectives and follow them up.

Some strategic owners have a selection of board members whom they follow up through board seminars and other forms of competence building. Furthermore, the board representatives may be rotated through the companies in the portfolio, both as part of capacity-building and knowledge-sharing, and also to ensure that at any time the boards have the right expertise for the challenges which the particular companies face.

Typical examples of long-term strategic owners are Investor and Industrivärden of Sweden and state holding companies such as Temasek (Singapore) and Khazanah (Malaysia).

To succeed with long-term strategic ownership, it is necessary to have a broad range of expertise, and it is crucial for the owners to have sufficient industry knowledge to follow-up the portfolio companies properly.

2.2.3 Owners focused on operational involvement

Owners focused on operational involvement try to create added value by concentrating on fewer companies and using their expertise to support companies at operational level. In order to capitalise on the expertise they bring to the companies, such owners will primarily be sole owners or, as a minimum, majority owners. The portfolio will typically consist of 10–50 companies.

Owners who are involved at operational level will actively undertake operational improvements in partnership with the management. The owners will ensure that there are regular reviews of value creation in the portfolio companies, and they will develop ambitious plans which they follow up closely. They will often drive functional thematic changes across the portfolio, for example through initiatives aimed at cost control, recruitment and so forth. These owners will also seek to create and exploit synergies between the companies in their portfolio, for example by having common procurement functions, IT solutions and other shared operational solutions. The best of these investors are good at building centres of excellence in different areas which the companies in the portfolio can benefit from.

Examples of such owners are the most actively involved private equity investors and large conglomerates such as General Electric.

The expertise required for good owners focused on operational involvement will vary greatly, depending on how they choose to be involved and will depend on the individual company’s situation and strategy.

2.3 Trends and developments in the exercise of ownership

2.3.1 Polarisation between passive and active owners

Over recent decades, there has been a gradual trend towards more fragmented ownership in listed companies. Increased fragmentation of ownership means that the owners have fewer incentives (and reduced opportunities) for exercising active ownership.

The increasing level of passive owners is connected with the increase in institutional ownership. Institutional owners, such as pension funds, insurance companies and mutual funds, own a considerable share of the world’s listed companies.

Companies with a fragmented shareholder structure and a predominance of institutional owners are often referred to as «ownerless» companies, since they lack major direct owners with incentives for exercising active ownership. In such ownerless companies, a lot of power may be concentrated with the management, and it may be difficult to verify whether the management is acting on the basis of its own, potentially short-term financial incentives, or on the basis of long-term value creation for the owners. Institutional owners have fewer incentives to work for long-term value creation due to generally shorter term positions.

It is natural to draw parallels between the development of ownerless companies and the emergence of very active ownership communities. Passive ownership and ownerless companies have also been suggested as a contributory factor in the financial crisis.

Active ownership requires resources and therefore entails a cost. Passive owners can thereby realise a gain by having other owners assume the costs of active ownership. Problems associated with passive ownership are reflected in a variety of guidelines for corporate governance and company management. The UK Stewardship Code, a set of corporate governance principles aimed at institutional investors in the UK, established in 2010, requires that institutional investors have clear guidelines for the use of voting rights and that they report on voting activity. The UK Stewardship Code is monitored by the UK’s Financial Reporting Council which requires institutional investors to report on whether or not they adhere to the guidelines («comply or explain»). The problems are also reflected in, for example, the Hermes Responsible Ownership Principles from Hermes Fund Managers11, containing principles for what companies should be able to expect from investors, including a constructive dialogue with the board and management and a long-term view in the exercise of ownership, including the use of voting rights.

2.3.2 Faster global industrial and technological developments

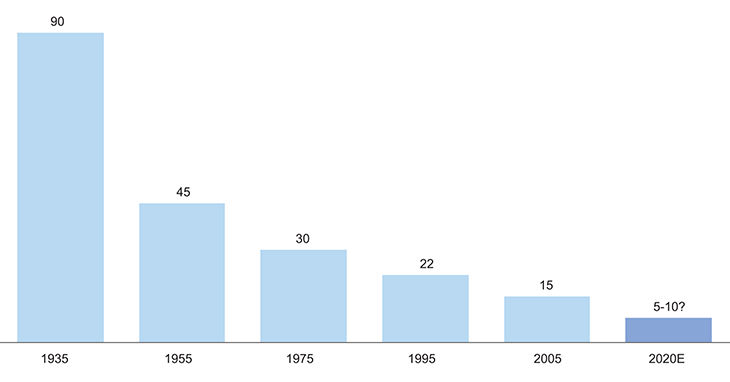

Companies must take into account increasingly more rapid changes in their surroundings and greater uncertainty and volatility in the global markets. This makes it more difficult to maintain strategic competitiveness over time. For example, the companies’ average life time on the S&P 500 has fallen considerably over the last century; see figure 2.2. This trend is powered by a number of different factors.

Figure 2.2 Average life time of companies on the S&P 500. Implied life time in number of years based on average loss of tenure over a 20-year period.

Source McKinsey & Company.

Firstly, technological changes are occurring more rapidly than before, and new technologies are gaining footholds in the market ever more rapidly. This means that innovations can quickly alter the dynamics of a sector. Technological developments may make companies which are market leaders today unable to withstand competition tomorrow if the company does not adapt fast enough and act innovatively. A well-known example is Nokia, which was the world leader in mobile telephony but which saw the value of its share capital reduced from 110 billion Euro to 15 billion Euro over five years after Apple, with the introduction of the iPhone, changed the competitive landscape.

Secondly, it is increasingly the emerging economies which are driving growth in the global economy. The growth in demand in these markets is making them increasingly important, including for Western companies, and creating a need for new expertise and experience. At the same time, a gradual dismantling of trade barriers and increased integration in the global economy has ensured that more industries have been opened up to competition.

Thirdly, the financial markets still bear the marks of the financial crisis of 2008, and the ensuing debt crisis in Europe. In Europe especially, the financial sector remains weak, and with low expected future growth, there are reasons to believe that Europe faces considerable challenges12.

In a world of keener competition and faster change, greater demands are made of management, boards, and owners to make good decisions quickly. The management should be able to evaluate operational opportunities and be more internationally oriented. The boards should be closer to the strategy process and have adequate international expertise and experience. The boards should, moreover, be able to represent the long-term perspective in a world where CEOs are replaced more frequently, and where greater unpredictability means that management has to concentrate more intently on short-term challenges. The owners should be prepared to assess decisive strategic changes, acquisitions and other major investments with less delay.

2.3.3 Growth in long-term state ownership with expansive agendas

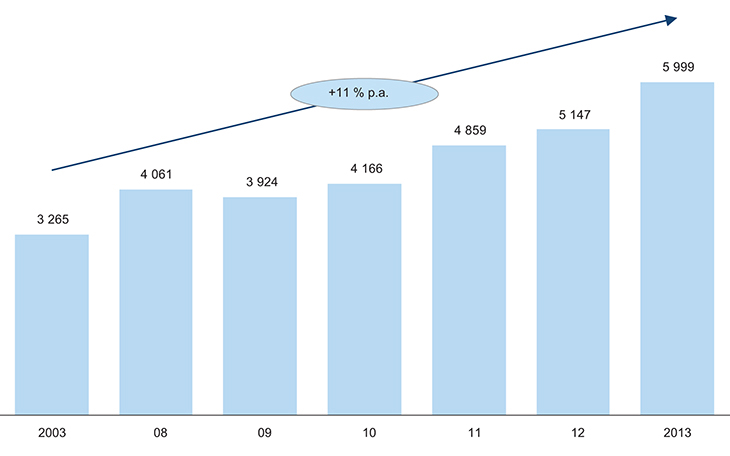

Large distortions in the global balances of trade have led to substantial national wealth accumulation in individual countries and hence greater state ownership in commercial companies. Through large sovereign wealth funds, especially in China and the Middle East, state agencies own an increasingly larger proportion of the world’s share capital. The extent of sovereign wealth funds is shown in figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 Sovereign wealth funds in the period 2007–2013. Capital under administration in USD billions.

Source Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute.

State ownership has also grown nationally, powered to a great extent by state acquisitions in connection with the financial crisis. This applies in particular to the financial sector where a number of insurance companies and banks have been placed under state control. Moreover, a number of large, substantially state-owned, companies have expanded globally. This scenario is especially evident among Chinese companies but is also illustrated through, for example, the expansions of Telenor and Statoil in the early 2000s.

State investment and pension funds are fundamentally organised in the same way as large private funds and often operated under similar principles. Many states also use state-owned enterprises to protect national interests, for example by safeguarding access to commodities or for promoting industrial development in their own countries. In Norway, the national maintenance of key functions in the country is an important argument for retaining majority or negative control (more than one third) in certain Norwegian companies.

In many countries, there has been a professionalisation of state ownership, with clearer division of responsibilities between regulatory authorities and the state’s exercise of ownership. Communication with the international investor market, in order to explain how state ownership functions, is hugely important for trust in state ownership. Even if state owners act professionally and transparently, it will still be increasingly more important for them to be open and clear about the guidelines which apply to their exercise of ownership and how these are adhered to.

2.3.4 Greater expectations of responsible ownership

In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to a number of problems associated with owners’ and companies’ social responsibilities. Environmental challenges, multinational companies’ role in developing countries and corruption cases are areas which have received great attention.

At the same time, there has been a large increase in funds and other investors focused on sustainable investments. Examples of such funds are Osmoris MoRE World, Generation and GS Sustain. In addition, many investors who do not treat sustainable investments as a separate concept have introduced better systems for reducing risks relating to corporate social responsibility in their portfolios.

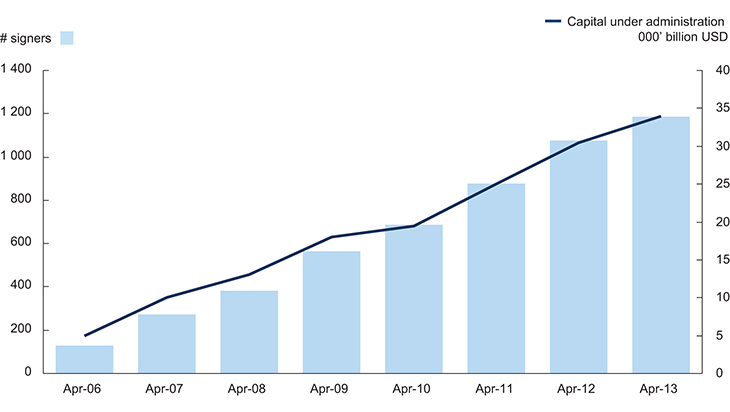

In 2006, the UN Principles for Responsible Investment were formulated. Adherence to the UN principles has increased to more than 1,200 investors who, combined, administer capital valued at more than USD 34,000 billion; see figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4 Number of investors who have signed up to the UN Principles for Responsible Investment.

Source Principles for Responsible Investment.

The fact that owners are increasingly emphasising their social responsibility and associated improved routines for compliance, places more pressure on other owners to follow suit, as the reputational risk of not following the best example increases. For owners, there is therefore an increasing need to ensure they have good systems and routines for monitoring corporate social responsibility in different areas, and many trends indicate that this may become a competitive advantage for companies and shareholders in the future.

2.3.5 Increased awareness of the long-term value trend of companies

Many people have argued that the focus on short-term gains contributed to the financial crisis13. This crisis and the ensuing debt crisis in Europe have put a critical spotlight on short-term market participants. Such turbulence also goes to undermine confidence in companies and owners.

A survey14 of business leaders across a number of countries shows that they experience pressure to produce short-term results, and 63 per cent of respondents stated that the pressure has increased in the last five years. Nearly half reported that they worked to a strategy with a time horizon of less than two years. At the same time, 73 per cent of respondents stated that the planning horizon should be three or four years or more. It is therefore the case that a majority of business leaders see the planning horizon as non-optimal due to pressure from outside or from greater competition.

The boards will therefore be increasingly more important for guaranteeing a long-term planning horizon. The best boards are also increasingly involved in strategy work and spend more than half their time on this.

2.3.6 Increase in activist investors

Activist investors represent a phenomenon that has grown strongly in recent years. Capital administered by activist funds grew more than sixfold in the period 2003–2013, and activist investors are taking positions in increasingly larger companies15. The growth has not shown any tendencies to flatten out, so it is reasonable to assume that this is a trend that will continue in the years ahead.

Activist investors are commercially oriented investors who acquire small shareholdings in a company and attempt to increase the value of the investment by trying to force through changes in the company’s governance. The objective for activist investors is to buy into companies they believe have a large potential for improvement and with clear plans for measures to boost the companies. If their plans fail to make an impact, they will attempt to force through their agendas by initiating a campaign against the management. The value creation model of activist investors is to buy into companies they believe lack good corporate governance.

Typically in the USA, activist investors often prepare an in-depth analysis (a white paper) of the target company. Based on this analysis, detailed proposals or requirements are put forward which the management and board are requested to implement16. The proposals might, for example, entail splitting of the business, the sale of subsidiaries, larger dividends, arranging for acquisitions and other transactions of a clear commercial and operational character. The proposals are often combined with communication campaigns, TV appearances, shareholder letters, newspaper articles, etc. Calculations by FactSet17 show that activist shareholders succeeded fully or partially in their campaigns in six out of ten cases in 2013. According to The Wall Street Journal, this was the highest figure ever.

The activist investor trend is strongest in the USA, but has also spread to Europe. However, compared with the USA, the campaigns of activist investors in the EU and Norway have been less vocal. Activist investors have been active in the Nordic region for a number of years; for example, Stockholm-based Cevian Capital took a 16 per cent holding in Lindex in 2003 and replaced much of the management18. In the Nordic region, the frequency of activist actions looks set to increase, and Cevian is now the largest activist investor in Europe19. Internationally, there have also been cases where activist investors become involved in companies with few dominant owners.

Activist investors are a controversial topic, the term often has negative associations and they are often criticised for taking short-term gains. However, analyses indicate that activist investors generally have a positive effect on companies’ returns, including in the longer term20. For management and boards, attacks from activist investors are likely to be unwelcome since they imply that the management should have done a better job. For other owners, this may potentially be a benefit. In some cases, activist investors will be invited in by other long-term investors or by concerned employees who are dissatisfied with the management21. In other situations, the threat of activist action may itself prompt change.

2.3.7 Effective board work has become a more important competitive factor

Before the financial crisis of 2008, there was a long period of stability and high economic growth in the global economy, often referred to as «The Great Moderation». Long periods under a favourable economic climate placed relatively less pressure on the boards than is the case today. The boards’ duties and responsibilities were therefore often limited, and many boards essentially restricted themselves to approving the executive’s proposals. The dot-com crisis, the financial crisis and a series of major bankruptcies contributed to considerably increasing the demands placed on the boards. In many jurisdictions, the formal requirements have also been strengthened. The board is increasingly being viewed as a crucial factor for the company’s long-term success. The company’s various support functions have gradually become more professionalised, and in many respects the board is the last link in this chain.

This development has been driven by a number of factors. As previously mentioned, the pace of technological development, globalisation and financial market turbulence have meant that companies need to deal with greater uncertainty and faster changes in the market than before. In addition, digitisation, globalisation and new business models have made the companies more complex and therefore more difficult for the boards to control. More frequent changes to executive management mean that it falls to the boards to safeguard the long-term prospects of the companies to a much greater degree. Following the financial crisis, the media also scrutinised the boards more carefully in the event of irregularities in a company, with ensuing discussions of the boards’ qualifications and what they spent time on.

McKinsey’s Global Board Survey 2013 indicates that many directors continue to find that they have insufficient time, knowledge and the appropriate information to contribute effectively, but that this is changing. Over the last five years, directors have found that the boards have become more effective, and the time spent on strategy activities has increased. Nonetheless, the survey indicates that board members believe that a further increase in the time spent on strategy would produce greater value for the companies in the years ahead22.

The boards increasingly aspire to become more professional. At the same time, there are increased expectations of the boards taking an active role in order to be able to add value to the organisation. High-functioning boards, which operate as effective sparring partners and challengers to the management, will be increasingly more important components of well-run companies.

Footnotes

OECD (2004): «Corporate Governance Principles.»

See, for example, Wolf, C. (2009): «Does Ownership Matter? The Performance and Efficiency of State Oil vs. Private Oil (1987–2006).»