5 Spatial management – challenges and coexistence between industries

5.1 The spatial element of the management plans

The intensive use of the North Sea and Skagerrak puts considerable pressure on these waters, and it is important to maintain the renewable resources and prevent damage to the marine environment.

The main aim of this chapter is to discuss the challenges associated with spatial overlap between different commercial activities, such as petroleum activities, fisheries, maritime transport and offshore wind power. Chapters 3, 6 and 7 discuss how to keep a balance between sustainable use and conservation of ecosystems. The white paper Protecting the Riches of the Sea (Report No. 12 (2001–2002) to the Storting) stated that the expected increase in the use of coastal and marine areas will make it difficult to strike a balance between the various user interests and environmental considerations, so that spatial planning in marine areas will be an important tool. A differentiated and sustainable spatial management regime must be based on knowledge of ecosystems and the impacts of different forms of use. Digital mapping tools are extensively used in the management plans to illustrate different types of use and protection of marine areas.

A comprehensive scientific basis has been compiled for each of the management plans for Norway’s sea areas, and the plans include a number of general decisions about spatial management. A digital mapping management tool will simplify and rationalise the process of updating the plans. It will also make the scientific basis and decisions regarding spatial management more readily accessible, and allow them to be presented in a coherent and visual manner.

5.2 International developments

The ultimate aim of maritime spatial planning in the EU and other countries and international organisations is to plan human activities in areas of sea that are outside the baselines but under national jurisdiction while at the same time protecting marine ecosystems.

The 2007 EU Integrated Maritime Policy identified maritime spatial planning as a key tool for integrated marine management. The 2008 EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive also refers to the use of digital management tools for achieving good environmental status in European marine waters.

In March 2013 the European Commission presented a proposal for a directive establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning and integrated coastal management that emphasised an ecosystem-based approach and the importance of coordinating sectoral interests. The proposal establishes a framework for maritime spatial planning and integrated coastal management in the form of a systematic, coordinated, inclusive and transboundary approach to integrated maritime governance. It obliges member states to carry out maritime spatial planning and integrated coastal management in accordance with national and international law. The geographical scope of the directive includes internal waters and extends to the external border of the member states’ national jurisdiction in marine areas.

The proposed directive will be considered in the EU. The EEA relevance of the directive will be considered in accordance with the normal procedure.

The UN system, in particular through the International Oceanographic Commission (IOC) under UNESCO, has issued a guide to a step-by-step approach to ecosystem-based management and set up a website to help countries implement it in practice. The methods described here are also relevant to Norwegian conditions.

In 2003 the OSPAR Commission appointed a working group on marine spatial planning. OSPAR has also published the OSPAR Guidance on Environmental Considerations for Offshore Wind Farm Development, which includes the issue of conflicts of interest.

In 2010, it was decided at a Ministerial Meeting of the Helsinki Commission (HELCOM), which is the governing body of the Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area, that marine spatial plans should be developed for the Baltic Sea through close cross-border cooperation. Under the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region, the EU countries bordering on the Baltic Sea have set a target for marine spatial planning to be in place by 2015.

In 2011 the Swedish Government established the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management, whose responsibilities include marine spatial planning. Marine spatial plans are to be developed for three areas: the Gulf of Bothnia, the Baltic Sea, and the Skagerrak. In the UK the Marine and Coastal Access Act of 2009 contains provisions relating to marine planning and established the Marine Management Organisation. Guidelines for marine planning were issued in 2011 and marine plans are being developed for inshore and offshore waters.

The countries that have made most progress are the Netherlands, Germany and Belgium, all of which have developed marine spatial plans. They make extensive use of maps to show areas and features that are used or protected in different ways and to clarify their legal status.

Countries outside Europe are also engaged in marine spatial planning, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand and a number of other countries. The US has developed recommendations for coastal and marine spatial planning.

Cooperation between the countries around the North Sea and Skagerrak is crucial, both to address problems in these sea areas and to exchange experience of integrated marine management.

5.3 Spatial overlap between activities in the North Sea and Skagerrak

5.3.1 Spatial overlap between maritime transport and fisheries

Under normal circumstances the main conflict of interest between maritime transport and fisheries arises when cargo vessels sail through or very close to fishing grounds where there are large concentrations of fishing vessels. This is primarily a question of safety, especially for smaller vessels. Some fishing vessels operate on their own, are small and can be difficult to see in poor light. They may also be difficult to capture on radar if there is a lot of background noise.

Large concentrations of fishing vessels in the path of a shipping route make it necessary for ships to deviate considerably from their course to avoid the risk of collision.

Over the years several collisions have occurred between cargo vessels in transit along the coast and vessels engaged in fishing. In some cases this has resulted in shipwreck and loss of life, while in others it has only damaged the vessel.

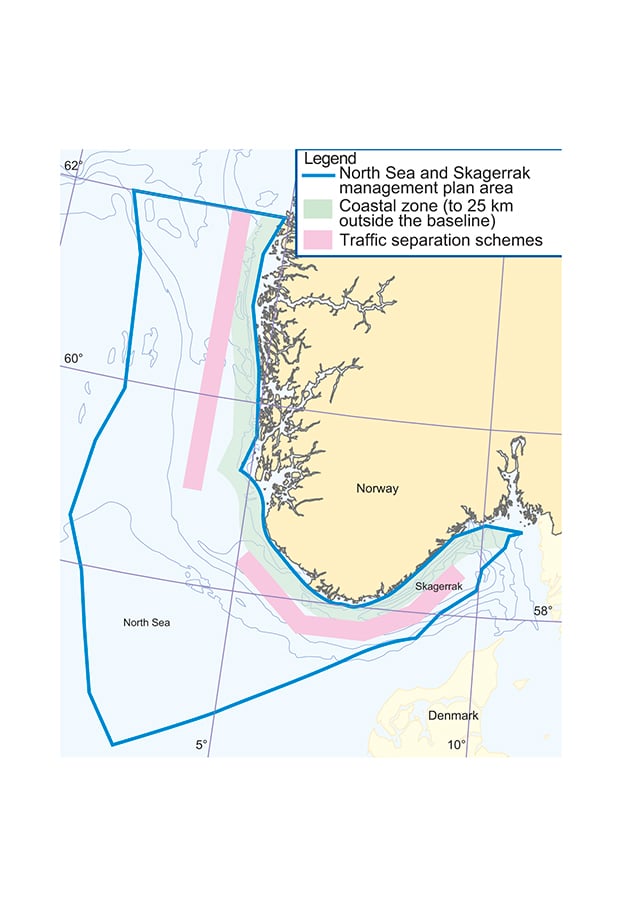

Figure 5.1 Traffic separation schemes in the North Sea and Skagerrak

Source Norwegian Coastal Administration, Directorate for Nature Management, Norwegian Mapping Authority

On 1 June 2011, new traffic separation schemes and recommended routes were introduced off Western and Southern Norway for vessels of gross tonnage of 5 000 and over, and for vessels carrying dangerous or polluting goods. These ships now sail further away from the coast and the potential for conflicts with the fisheries has been considerably reduced.

Ships may also damage fixed fishing gear or markers for such gear.

Wrecks on the seabed may obstruct fishing. The Nairobi International Convention on the Removal of Wrecks (Wreck Removal Convention) was adopted by IMO on 18 May 2007. The Convention contains provisions on locating, marking and removing ships and wrecks. Although the Convention primarily applies in the exclusive economic zone of a state party, a coastal state may notify IMO that it will extend the application of part or all of the Convention to wrecks located in its territorial sea and internal waters. Norway is considering whether to ratify the Convention and incorporate it into Norwegian law.

There are international rules for the conduct of ships towards vessels engaged in fishing, and the location of important fishing grounds was taken into account in the process of establishing traffic separation schemes along the coast. The schemes channel ships in transit along fixed routes. Conflicts usually only arise when a particular ship fails to obey the rules and thereby increases the risk of a major or minor accident.

The establishment of maritime corridors along the entire Norwegian coast, together with the reduction in the number of fishing vessels, makes it unlikely that the level of conflict will be any higher in 2030 than it is today, even with an increase in traffic.

The rules should be tightened up to make it possible under certain circumstances to require the removal of wrecks that interfere with fishing operations. At present the main grounds for removing wrecks are their presence in a nature reserve or the environmental risk they pose. If a wreck is allowed to remain, its position must be made known, clearly and accurately, to the fishing fleet.

In addition to the above, the most effective means of promoting coexistence between shipping, fisheries and other industries (aquaculture, offshore wind power, etc.) are visual or electronic marking and routeing schemes.

5.3.2 Spatial overlap between maritime transport and offshore wind power installations

Offshore wind power developments would require certain restrictions on the use of the areas around installations that could affect maritime traffic. In many cases conflicts of interest could be resolved by measures such as altering maritime routes or establishing corridors between wind turbines. The Water Resources and Energy Directorate conducted a strategic impact assessment of offshore wind power development based on the 2010 report identifying Norwegian sea areas suitable for such development (the Offshore Wind Power Report), and in this connection the Coastal Administration assessed the impacts of wind power development in these areas on maritime traffic, navigation, and safety and emergency preparedness.

In the Olderveggen and Utsira North areas, offshore wind farms would have major impacts on maritime traffic. However, for Utsira North the impacts could be reduced by reducing the size of the area developed. Wind power development in Southern North Sea II and Frøyagrunnene is assessed as having moderate impacts on maritime traffic. Development in Southern North Sea I and Stadhavet is assessed as having little impact on maritime traffic because the two areas are situated in the open sea where traffic density is relatively low.

The main measure to mitigate impacts on maritime traffic would be to limit the size of the areas opened for wind power development. Other measures would have to be considered for the individual developments, for example alterations in fairways or maritime routes, or removal or alteration of aids to navigation.

Procedures for resolving conflicts between maritime transport and offshore wind power development should be clarified before any development takes place.

5.3.3 Spatial overlap between the petroleum and fisheries industries

Oil, gas and fish are Norway’s most important exports, and ever since oil and gas activities started on the Norwegian shelf about 40 years ago, the authorities have emphasised the importance of coexistence with other industries, the fisheries industry in particular. This has laid the foundation for value creation based on Norway’s fisheries and oil and gas resources.

Occupation of an area by petroleum activities takes place in phases, which are either short- or long-term. Seismic surveys, exploration drilling, construction and field closure are short-term activities, while fixed installations occupy an area over the long term. Seismic surveys occupy the largest area. These surveys are conducted during all phases of petroleum activity, from exploration to final production. Even though seismic surveys only last for a relatively short time in each phase, this is the activity that leads to the greatest conflict with the fisheries.

Under Norwegian and international safety regulations, a safety zone is established around platforms and other permanent and dynamically positioned facilities or vessels that project above the sea surface. The safety zone is a geographically defined area within a distance of 500 metres from any part of an installation that unauthorised vessels are prohibited from entering, remaining in or operating in. The impacts of occupied areas depend on the position of the safety zones in relation to important fishing grounds and on the type of fishing gear used. The safety zones round petroleum installations are regarded by all parties as essential for safety purposes.

Exploration drilling occupies areas, although only temporarily, since a 500-m safety zone is established around the drilling facility or vessel. An exploration rig, including its anchor spread, occupies an area of about 7 km², in other words, an area considerably larger than the safety zone. Dynamically-positioned rigs will occupy a somewhat smaller area, while anchoring in deeper water will occupy a larger area. Drilling operations usually take two to three months.

During the development phase, after a plan for development and operation has been approved, there will be periods of varying length when smaller or larger areas are occupied, particularly in connection with construction and pipeline- and cable-laying. The size of the occupied area will depend on the development concept.

Under Norwegian law, subsea installations and pipelines must be designed to avoid interference with fishing operations. This means for example that they must be overtrawlable and constructed in such a way as to avoid damaging fishing gear. This means that safety zones are not established around subsea structures, including pipelines. In this respect, Norwegian legislation differs considerably from the rules in other part of the North Sea. In other countries’ zones, liability for damage to a pipeline lies with the operator who has caused the damage. In practice this means that there is no fishing in the neighbourhood of pipelines or subsea structures.

Fisheries using conventional gear such as gillnets and longlines, and pelagic fisheries using purse seines and pelagic trawls, are not normally affected by subsea structures.

The habits of sandeels are quite different from those of other fish. Sandeels spend long periods burrowing in sandy substrate. Suitable substrate is only found in clearly delimited areas, and the distribution of sandeels is therefore limited by the extent of their habitat.

In December–January, mature sandeels emerge from the sand to spawn directly above the substrate. The fertilised eggs are attached to sand grains until they hatch and the larvae drift in the water column. There are strong indications that each area of sandeel habitat has its own local sandeel stock. Since both the spawning grounds and the spawning period are limited, individual stocks are very sensitive to disturbance, unlike species that spawn over large areas and for long periods. Releases of pollutants from petroleum activities in the first-mentioned areas are therefore strictly regulated. To protect sandeel areas of habitat and spawning grounds, and avoid sediment deposition from drilling activities, discharges of drill cuttings are prohibited in the areas, and any field developments must be designed to minimise changes to benthic conditions in areas of sandeel habitat. Ways of minimising disturbance to spawning are also considered when drilling permits are issued.

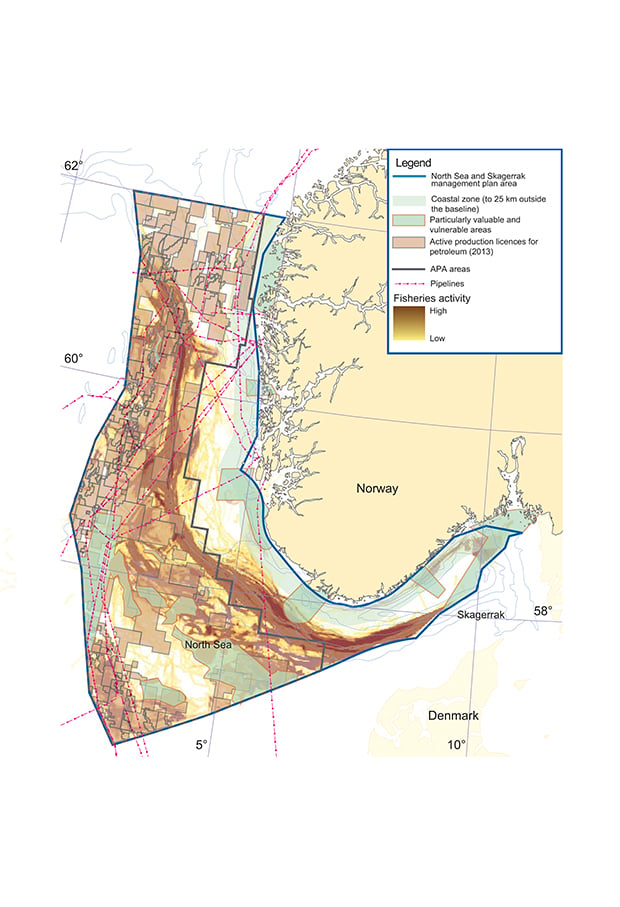

Figure 5.2 Petroleum and fisheries activities in the North Sea and Skagerrak

Source Norwegian Petroleum Directorate, Directorate of Fisheries, Directorate for Nature Management, Norwegian Mapping Authority

From April to the end of June sandeels emerge from the sand during the day to feed, and this is the period when they can be harvested and there is a sandeel fishery. Restrictions on petroleum activities have been introduced at this time of year to avoid conflict with the sandeel fishery.

Rock fillings are sometimes used to support or stabilise pipelines and at pipeline crossings. The fillings do not seem to cause particular problems for larger trawlers, but trials of overtrawling by smaller trawlers have shown that problems arise to a varying degree. Fishing gear may catch on or be damaged by a pipeline or cable with surface damage that lies on or is only partly buried in the seabed. Experience has shown that in practice fishing operators tend to avoid such areas. Thus pipelines may occupy areas in practice and result in reduced catches for vessels fishing in such areas.

The OSPAR prohibition on dumping of disused offshore installations has been incorporated into Norwegian law. This means that the authorities make the final decision on the disposal of oil and gas installations after shutdown based on a decommissioning plan, which includes an impact assessment. So far 44 offshore installations have been removed from the Norwegian part of the North Sea during decommissioning. As a general rule, pipelines and cables may be left in place provided that they do not constitute a nuisance or safety risk for bottom fisheries that is proportionate to the costs of burying, armouring or removal. This means that in practice they remain in place in areas where there are no important bottom fisheries or where they have been properly buried or armoured.

The rules allow for exemptions to be made from the prohibition on dumping and for certain specific categories of installations, primarily concrete installations, to be left in place. So far two concrete structures (the Ekofisk 2/4 tank and Frigg TCP2) have been left in place in the Norwegian part of the North Sea. Such structures have little negative impact on fish populations, but there may be conflict with fisheries interests because of restrictions on access to the area concerned.

5.3.4 Fish and seismic surveys

Seismic surveys are geophysical surveys that constitute the main source of information about conditions beneath the seabed. Seismic data are therefore needed to map petroleum deposits, and are crucial for maximising production from oil and gas fields. Seismic surveys are carried out in all phases, from exploration to production, and continued development of seismic surveying has always been played an important role in the development of the Norwegian petroleum industry.

Fisheries are a dynamic industry in the sense that there can be considerable variations in a fishery from one year to the next. However, knowledge and long experience have shown that certain areas and times of year are particularly important. To promote coexistence between fisheries and seismic surveying, the authorities have developed legislation to provide a clear framework and more predictable conditions for both activities.

The basic method used for seismic surveying is to discharge sound pulses from a vessel or other source on the surface, which travel down below the seabed. These are reflected back to the surface from the boundaries separating the geological layers under the seabed. The reflected signals are recorded by receptors, usually towed behind the vessel just below the surface.

Seismic surveying has been a source of conflict between the petroleum and fisheries industries. Several impact assessments for seismic activity have therefore been conducted, and a number of measures have been introduced.

With regard to the scare effect of seismic activity on fish, it is important to know how far away from the source of the noise the effect makes itself felt. Relatively little research has been done on scare effects and studies have shown conflicting results. The way sound waves travel and the distance travelled depend on horizontal and vertical salinity and temperature conditions, which vary through the year and often from area to area. Topography and seabed conditions also have a strong influence on the distance travelled by sound under water. The authorities have therefore refrained from setting a recommended minimum distance between seismic activity and fishing activities, fish farming, and whaling and sealing. However, the legislation does require seismic survey vessels to maintain a reasonable distance from vessels engaged in fishing and from fixed or drifting gear.

The relatively few studies on the scare effect agree that there are large differences in the scale of the effects. For example, in a 1992 study in the Nordkapp Bank area, the Institute of Marine Research found a reduction in trawl catches of cod and haddock within a radius of 18 nautical miles of a seismic vessel. However, apart from the studies on cod and haddock, little research has been done in this area, especially with regard to the effects of seismic activities on pelagic species.

In the last 20 years the technology used in seismic data acquisition has reduced the impacts on the fisheries. In summer 2009, the Institute of Marine Research carried out a research project in connection with seismic data acquisition by the Petroleum Directorate in the waters off the Lofoten and Vesterålen Islands. The study showed that the noise affected fish behaviour and that there were changes (increases or decreases) in the size of catches while the surveys were being conducted, depending on the gear being used and the species involved. No specific distance was found for the scare effect, but the recorded distances were considerably shorter than the distance observed in the Nordkapp Bank area in 1992. The Institute’s report concluded that no injuries to fish had been recorded as a result of seismic activities. Other studies have shown that generally speaking seismic activities do not in themselves injure marine life, although injury to fish eggs and larvae within a radius of 5 m of the source of the noise has been reported. However, the Institute of Marine Research has concluded on the basis of previous studies that such damage is not significant at population level.

There is an annual handline fishery for mackerel in the North Sea. It takes place during a limited period in late summer and autumn, mainly from small vessels with a limited action radius. This is an important fishery for around 150 vessels. Handlining gear is used in the upper part of the water column, where the effects of noise are greatest. In addition, mackerel are fast swimmers and particularly sensitive to noise, which causes them to swim rapidly away from noise sources. For several years there has been a conflict between seismic surveying and handlining for mackerel in the northern part of the North Sea. In early summer 2012, it became clear that some planned seismic surveys could come in conflict with handlining for mackerel. The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy and the Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs have developed joint guidelines for addressing cases of overlapping interests. They were used to deal with the cases above, and during the process the parties were encouraged to cooperate on finding solutions.

In summer 2012 a pilot project was carried out with a view to establishing a mechanism for dealing with possible conflicts between seismic surveys and the mackerel handline fishery. In the project, seismic data acquisition was put on hold in specific cases based on regular assessments, to enable the mackerel to move away without being disturbed by seismic activity. When it became clear that catches in the area were low, partly because the fish had moved closer to land, seismic activity was resumed on the understanding that it would be halted again if necessary. The parties involved in the project (Statoil, the Norwegian Fishermen’s Association and the Directorate of Fisheries) have evaluated the project, and agreed that the 2012 season had proceeded without serious conflict between the fishery and the seismic surveys. The project contributed significantly to the lack of conflict, helped by the fact that the mackerel migration pattern changed in 2012. The project is being continued in 2013.

Cooperation between authorities, industry and organisations has resulted in a number of measures, including amendments to the Resource Management Regulations and the Petroleum Act and appurtenant regulations and measures to promote communication, coordination and competence-building. The amendments to the Resource Management Regulations include requirements for fisheries experts on board seismic vessels to follow a training course on seismic surveying and small adjustments to the requirements for reporting surveys and the tracking of seismic vessels. The Petroleum Directorate has established a web-based system for the reporting and notification of seismic surveys that allows interactive searches of data that has been reported and notifications of surveys. A cooperation agreement has been concluded between the Norwegian Coast Guard, the Directorate of Fisheries and the Petroleum Directorate under which the Coast Guard is the primary point of contact for fisheries experts. Guidelines have been introduced on how to resolve disagreements between the Directorate of Fisheries and the Petroleum Directorate regarding individual surveys. The Directorate of Fisheries has for several years been intensifying its efforts to supply information on fisheries activities to rights-holders and/or seismic companies, and has been involved in training fisheries experts on board seismic vessels. Incorporating such information into the planning and operational phases can make seismic surveying more effective.

In the course of 2012, the authorities considered a number of additional measures to improve coexistence. If seismic surveying in the North Sea can start earlier in the year than has been usual until now, it may be possible to show more flexibility in the planning of surveys. In this connection petroleum companies are now able, in consultation and close cooperation with the Directorate of Fisheries and the Institute of Marine Research, to plan seismic data acquisition so that it is carried out in a more flexible way than can be done when the starting time is fixed. For example, this will make it possible to complete a larger number of surveys before the start of the handline fishery for mackerel.

The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy and the Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs will take the initiative together with representatives of the business sector to institute an annual meeting on seismic surveying. The aim will be to reduce the likelihood of conflict between fisheries activities and seismic surveying. The meetings will therefore be held in time to apply to surveys in the coming season. Discussing possible areas of conflict and how to adapt seismic surveying in terms of time or through coordination between the parties will reduce the risk of conflict.

The Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs and the Petroleum Directorate have also decided to draw up guidelines for seismic surveying in order to clarify the existing legislation and processes and thereby promote sound planning and coordination of activities.

Parallel with these efforts, the Norwegian Oil and Gas Association is developing guidelines for the petroleum industry for planning and carrying out seismic surveys. They will be made publicly available so that the information can also be used on board fishing vessels.

Most seismic surveys do not lead to problems with fisheries. Although the authorities have implemented a number of measures to ensure cooperation between petroleum and fisheries activities, in the form of legislative amendments, improved communication and competence-building, it is important to keep up the work and continue the process of promoting further cooperation between the two industries. The aim is to strike a balance that promotes long-term, sustainable management of marine resources and ensure that cooperation continues to function smoothly in the years ahead.

The measures already implemented, combined with those that are planned, such as the new guidelines, seem likely to improve the situation in cases of spatial overlap between petroleum and fisheries activities.

5.3.5 Spatial overlap between petroleum activities and offshore wind power

If offshore wind farms are established, it will be difficult to carry out seismic surveys and exploration drilling to map petroleum deposits, and also to carry out oil and gas production, in the same area as the wind farms. In preparing the Offshore Wind Power Report described in Chapter 4.4, the working group took full account of important areas for petroleum exploration and production. The possible impacts on petroleum activities of the establishment of wind farms were also assessed in the subsequent strategic impact assessment, on the basis of information from the Petroleum Directorate.

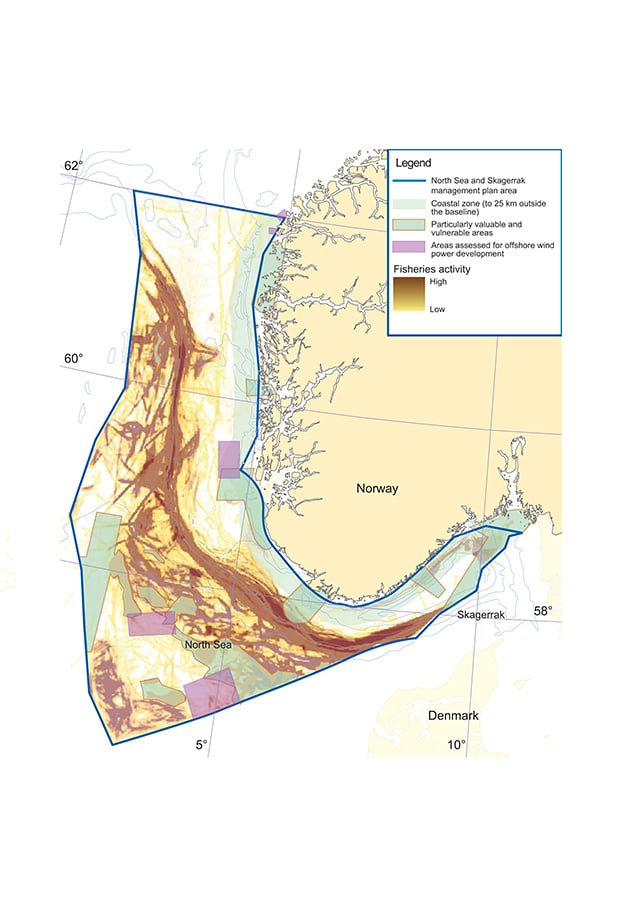

Figure 5.3 Fisheries activities and areas included in the strategic impact assessment for offshore wind power in the North Sea and Skagerrak.

Source Directorate of Fisheries, Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Directorate for Nature Management, Norwegian Mapping Authority

Conflicts of interest with the petroleum industry in the event of offshore wind power development in each of the areas considered in the strategic impact assessment for offshore wind power will primarily depend on the resource potential of the area. Existing infrastructure and the available area are also important factors. Of the five areas in the North Sea, Southern North Sea I and Southern North Sea II have the greatest petroleum resource potential. The Petroleum Directorate concluded that the impacts on petroleum activities in these areas would be moderate. For Stadhavet, the impacts on petroleum activities were assessed as minor. The impacts in Utsira North, Frøyagrunnene and Olderveggen were assessed as insignificant.

The assessed sea areas are large, and it is generally considered likely that solutions can be found that would allow several interested parties to coexist. If offshore wind farms are established in the management plan area, efforts will be made to resolve any overlapping interests through processes prior to a development.

5.3.6 Spatial overlap between fisheries activities and offshore wind power development

The establishment of offshore wind farms would affect fisheries, since fishing vessels would be prevented from fishing inside the area occupied by wind power installations or within a certain distance of turbines.

Fishing activities take place in all the areas that have been assessed, so that wind power developments in any of them would have impacts on the fisheries. The Directorate of Fisheries assessed the conflict potential in the areas in connection with the strategic impact assessment. The impacts were assessed as severe for Olderveggen and Frøyagrunnene, and as major for Stadhavet. However, Stadhavet contains several smaller areas with less fisheries activity and the impacts on the fisheries will decrease southwards. The impacts for Utsira North and Southern North Sea I and II were assessed as minor, and in some smaller areas as insignificant.

The impacts on fisheries would depend strongly on the size of the areas occupied by wind farms, on the regulations governing fisheries in and around wind power installations, on any adjustments that have to be made to take these into account, and on which types of gear it would be possible to use in the area.

Many areas that are suitable for wind power development overlap important fishing grounds, and it will be essential to involve local fisheries interests at an early stage of the detailed planning and licensing processes. Since the assessed areas are larger than is needed for one wind farm, it should be possible to avoid or reduce conflicts by adapting development to local conditions and interests.

5.4 The need to strengthen the spatial element of the management plans

5.4.1 Existing databases and portals

An important step in strengthening the spatial element of the management plans for Norwegian sea areas is to ensure that there are appropriate data and tools available. There are already several databases and portals that provide information on Norwegian sea areas. The following deserve particular mention:

BarentsWatch is being developed as a comprehensive monitoring and information system for marine and coastal areas. Around 30 partner institutions cooperate on the portal, headed by the Coastal Administration, and the information is based on updated, quality-assured data supplied by the partners. BarentsWatch will also have its own portal for publishing information for the authorities and the maritime sector, and a further aim is to supply new, specialised services. Priority is given to providing good real-time information.

The website miljøstatus.no is a channel for dissemination of information on the state of the environment and environmental trends, maintained by the environmental authorities. The maps module includes maps on a range of topics related to marine and coastal waters, which supplement articles on various topics and descriptions of indicators. There are map layers on environmental status (for example on coral habitats and vulnerable habitats), activities (aquaculture, maritime transport), fish and crustaceans (mainly indicator species), ocean currents and depths, oil and gas (fields, installations and offshore emissions), marine mammals (indicator species) and energy, including areas that have been assessed for offshore wind power development.

The website havmiljø.no is a tool for displaying the assessed ecological importance and vulnerability of Norwegian waters. Areas are assessed particularly in terms of their biological productivity, importance for threatened species and/or habitats, and species biodiversity and density. The assessments are based on the most recent data from the monitoring programme for seabirds (SEAPOP), the mapping programme for the seabed (MAREANO) and other national sources, and have high temporal and spatial resolution. There are also map layers showing various aspects of the natural environment, administrative boundaries and human activities. These can be supplemented by other information, for example on the conditions specified in licences for petroleum activities.

These websites are mainly based on databases developed and maintained by a number of different agencies and research institutions such as the Coastal Administration, the Norwegian Mapping Authority, the Norwegian Polar Institute, the Petroleum Directorate, the Climate and Pollution Agency, the Directorate for Nature Management, the Institute of Marine Research, and the Norwegian Institute for Water Research. Altogether these databases and portals provided a very sound basis for work under the management plans. However, additional functionality should be developed to meet the requirements for an interactive digital mapping tool. Moreover, the existing tools do not meet the necessary requirements for uniform, standardised use of symbols and colour schemes or presentation of the spatial management element of the management plans.

5.4.2 Developing a tool for the spatial management element

As mentioned elsewhere in this management plan, maps are widely used to illustrate spatial information, such as areas where a framework for petroleum activities has been adopted, areas where vulnerable benthic animals are found, and important spawning grounds. Together with the written text and the scientific basis, maps provide a good picture of the topics discusses in this and the other management plans.

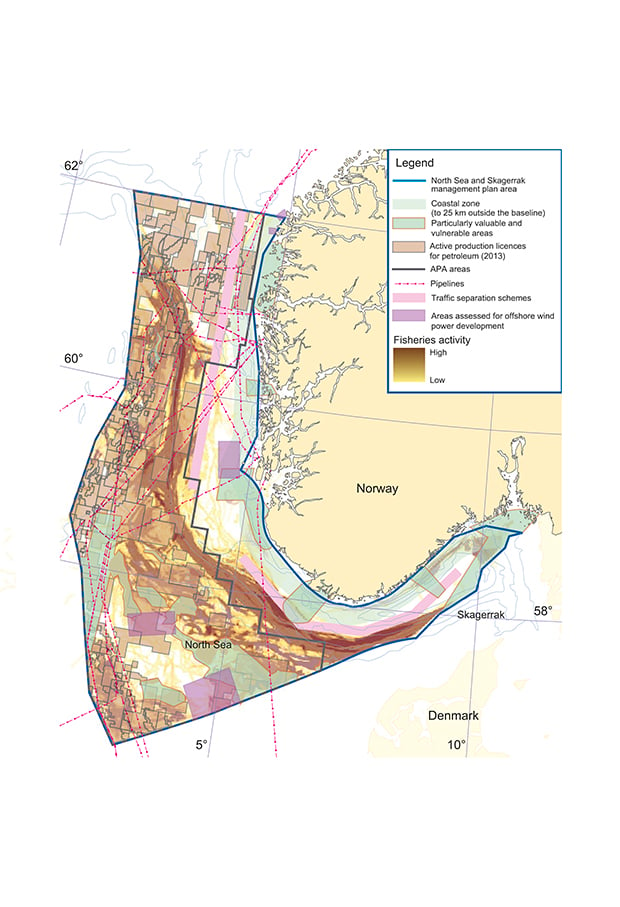

Figure 5.4 Overview of activities in the North Sea and Skagerrak

Source Petroleum Directorate, Directorate of Fisheries, Directorate for Nature Management, Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Norwegian Coastal Administration, Norwegian Mapping Authority

However, there are no mapping tools that provide integrated information on all the activities for which the authorities have developed overall frameworks under the management plans. A tool of this kind would provide an overview of the most important spatial frameworks determined in the management plans and would be a useful tool for the authorities, business sector, other users of the sea areas and the general public.

The overview could be supplemented with map layers for the most important industries, resources, species and habitats, and so on. This would provide a flexible system in which map layers for different topics could be overlaid and maps of different parts of the management plan area produced. For example, it should be possible to display up-to-date information on the legal status of any restrictions and guidelines established under the relevant legislation.

The main objective of this tool would be to rationalise the process of updating the management plans. It would provide a better overview of the spatial management decisions and measures implemented under previous plans. It would also help identify the political considerations that should be taken into account in future updates. Furthermore, it would ensure a more inclusive process by increasing transparency, and strengthen stakeholder participation in the work on the plans.

The tool could also be a source of information on the content of and scientific basis for the management plans and on developments in the various sea areas. It should be possible to illustrate activities on the surface, in the water column, and on and beneath the seabed.

To ensure that they are easy to use, all map layers will have to be based on the same background map and use standardised symbols, colours and so on.

The digital mapping tool must be developed within the framework of the work on the management plans and in close cooperation with the authorities responsible for the various portals and databases. It should also be able to serve as a platform for cooperation with other countries on management and maritime spatial planning.