7 Strengthening the legislation and the management regime

7.1 Legislative developments

The legal basis for implementing an integrated, ecosystem-based management regime for marine and coastal waters is provided by a number of Norwegian acts and regulations. These are administered by the Ministry of the Environment or other ministries, particularly the Ministries of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs, Petroleum and Energy, Trade and Industry (shipping) and Labour and Social Inclusion (inspection and enforcement in the petroleum industry), see Box 7.1. All in all, this legislation provides a sound and comprehensive basis for the management regime. On 1 January 2009 the new Marine Resources Act entered into force, and a Nature Management Act has been presented in Proposition No. 52 (2008–2009) to the Storting. These will further strengthen and update the legislation. The Marine Resources Act emphasises the precautionary principle and the ecosystem approach as a basis for fisheries management. The precautionary principle is also a key element of the Nature Management Act, together with knowledge-based management, assessment of cumulative environmental effects, and the user-pays principle. See Boxes 7.1, 7.2, 7.3 and 7.4 for more information.

The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy has started a public consultation on the draft Marine Energy Act, which is to regulate the planning, development, operation and decommissioning of installations for renewable energy production and infrastructure for transmission grids outside the baseline.

Textbox 7.1 Legislation of relevance to integrated, ecosystem-based marine management

Act of 19 June 2009 No. 100 relating to the management of biological, geological and landscape diversity (Nature Management Act)

Act of 6 June 2008 No. 37 relating to the management of wild living marine resources (Marine Resources Act)

Act of 13 March 1981 No. 6 relating to protection against pollution and to waste (Pollution Control Act)

Act of 29 November 1996 No. 72 relating to petroleum activities

Act of 19 June 1970 No. 63 relating to nature conservation (Nature Conservation Act)

Maritime Safety Act of 16 February 2007 No. 9

Act of 11 June 1976 No. 79 relating to the control of products and consumer services (Product Control Act)

Act of 22 June 1990 No. 50 relating to the generation, conversion, transmission, trading, distribution and use of energy, etc. (Energy Act)

Act of 8 June 1984 No. 51 relating to harbours and fairways, etc. (Harbour Act). The Storting adopted a new act on 3 February 2009, but this has not yet entered into force (Proposition No. 75 (2007–2008) to the Odelsting)

Act of 29 May 1981 No. 38 relating to wildlife (Wildlife Act)

Act of 15 May 1992 No. 47 relating to salmonids and freshwater fish, etc.

Act of 19 December 2003 No. 124 relating to food production and food safety (Food Act)

Act of 16 June 1989 No. 12 relating to the pilot service

Applicability of the Nature Management Act in sea areas

The Nature Management Act will apply to all sectors that have an impact on or utilise nature and its diversity. The geographical scope of the Act includes Norway’s land territory and its waters out to the 12-nautical-mile territorial limit. However, the provisions on the purpose of the Act (section 1), management goals (sections 4 and 5), general principles of sustainable use (sections 7–10), the principle for the management of wild salmonids and seabirds (sections 15 and 16), and access to genetic material (sections 57 and 58) are also applicable on the continental shelf and areas under Norwegian jurisdiction beyond the territorial sea (12 nautical miles) to the extent appropriate.

Textbox 7.2 Key principles of the Nature Management Act

The precautionary principle (section 9)

When a decision is made in the absence of adequate information on the impacts it may have on the natural environment, the aim shall be to avoid possible significant damage to biological, geological or landscape diversity. If there is a risk of serious or irreversible damage to such diversity, lack of knowledge shall not be used as a reason for postponing or not introducing management measures.

The principle that cumulative environmental effects must be assessed (section 10)

Any pressure on an ecosystem shall be assessed on the basis of the cumulative environmental effects on the ecosystem now or in the future.

The provisions mentioned above will be generally applicable, and will thus supplement sectoral legislation when the authorities for specific sectors make assessments and decisions in accordance with such legislation, for example the Marine Resources Act and the Petroleum Act. The remaining provisions of the Nature Management Act will not be made applicable to Norway’s continental shelf or areas of jurisdiction established outside the 12-nautical-mile territorial limit. The Government will make a thorough evaluation of whether and in what way any other provisions are to be made applicable outside the territorial limit.

Rights to harvest or otherwise utilise wild living marine resources follow from the Marine Resources Act. The provisions on harvesting and other removal set out in sections 16, 20 and 21 of the Nature Management Act will therefore not be applicable to marine living resources. However, section 1 (purpose) and Chapter II (general principles of sustainable use) of the Nature Management Act will supplement the Marine Resources Act when the fisheries authorities make assessments and decisions on rights to harvest or otherwise utilise wild living marine resources under the Marine Resources Act.

The provisions on priority species will also apply in the sea out to the territorial limit. This paragraph will be particularly relevant if a species is rare or in danger of becoming extinct in Norway, or if a species needs protection across sectors.

The provisions of the Nature Management Act on alien species will apply out to the territorial limit, and have been harmonised with those of the Marine Resources Act and the Aquaculture Act. This means that any deliberate introduction or release of organisms to the sea within the territorial limit must be in accordance with the provisions of both the Nature Management Act and the Aquaculture Act. Outside the territorial limit, the management of alien species will be regulated by the Marine Resources Act and the Aquaculture Act. Species that themselves spread to areas under Norwegian jurisdiction (for example the red king crab and the comb jelly Mnemiopsis leidyi) are to be managed in accordance with the provisions of the Marine Resources Act. Species that have been introduced to sea areas in contravention of the Nature Management Act or as an unforeseen consequence of lawful activities are to be regulated by the provisions of sections 69 and 70 of the Nature Management Act. Species that were originally introduced and have become established in Norwegian waters are to be managed under the provisions of the Marine Resources Act.

The chapter of the Nature Management Act on protected areas includes a provision on marine protected areas, which applies out to the territorial limit. The provision provides the authority to establish purely marine protected areas. Such areas may be established on the grounds of their marine conservation value, but also to safeguard valuable marine areas that are ecologically necessary for terrestrial species. Marine protected areas may be established for a wide variety of purposes, and according to specific criteria that to a large extent correspond with those for the establishment of national parks, nature reserves and habitat management areas which are set out in sections 35, 37 and 38. When a marine protected area is established, it must be specified whether the purpose of the protection measure and restrictions on activities apply to the seabed, the water column, the water surface or a combination of these. This means that if fisheries are the only activity that must be regulated to achieve the purpose of protecting an area, restrictions would be imposed under the Marine Resources Act. Such areas would then be marine protected areas, but not protected areas under Chapter V of the Nature Management Act.

The provisions on selected habitat types will apply out to the territorial limit. Selected habitat types will be designated in regulations under the Act. In evaluating whether or not a habitat type is to be designated as selected, particular importance is to be attached to whether it is:

endangered or vulnerable,

important for one or more priority species,

a habitat type for which Norway has a special responsibility, or

a habitat type to which international obligations apply.

The substantive provisions on selected habitat types are intended as national guidelines on sustainable use for sectoral authorities and individual people. The provisions provide guidance for decision makers on the considerations that must be weighed up and the interests that must be safeguarded in managing selected habitat types. The provisions are therefore not intended to safeguard all areas of selected habitat types.

The provisions on access to genetic material will apply in Norway’s territorial waters out to the territorial limit, on the continental shelf and in areas under Norwegian jurisdiction beyond the territorial sea. There are similar provisions on the regulation of harvesting and sharing of the benefits of marine bioprospecting in the Marine Resources Act. The Act emphasises that Norway should manage genetic material as a common resource that belongs to Norwegian society as a whole. The utilisation of genetic material must be to the greatest possible benefit of people and the environment at both national and international level. Due regard must also be paid to fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilisation of genetic resources, so that the interests of indigenous peoples and local communities are safeguarded.

Regulations may be adopted under the Act introducing a general system of permits for harvesting and utilisation of genetic material. Furthermore, regulations may be adopted prescribing that the benefits arising out of harvesting and utilisation of genetic material from Norway shall accrue to the state. Both financial and non-financial benefits may be regulated.

The Nature Management Act and the Marine Resources Act contain very similar provisions on permits for harvesting biological material and sharing of the benefits arising from such activities. There are plans to regulate harvesting and utilisation in one set of regulations under both these acts, so that only one application process is necessary, and the fisheries authorities are responsible for the provisions of the regulations that apply to sea areas.

Textbox 7.3 Excerpts from the Marine Resources Act

Section 1 Purpose

The purpose of this Act is to ensure sustainable and economically profitable management of wild living marine resources and genetic material derived from them, and to promote employment and settlement in coastal communities.

Section 7 Principle for management of wild living marine resources and fundamental considerations

The Ministry shall evaluate which types of management measures are necessary to ensure sustainable management of wild living marine resources.

Special importance shall be attached to the following in the management of wild living marine resources and genetic material derived from them:

a precautionary approach, in accordance with international agreements and guidelines,

an ecosystem approach that takes into account habitats and biodiversity,

effective control of harvesting and other forms of utilisation of resources,

appropriate allocation of resources, which among other things can help to ensure employment and maintain settlement in coastal communities,

optimal utilisation of resources, adapted to marine value creation, markets and industries,

ensuring that harvesting methods and the way gear is used take into account the need to reduce possible negative impacts on living marine resources,

ensuring that management measures help to maintain the material basis for Sami culture.

The Marine Resources Act

The Marine Resources Act entered into force on 1 January 2009, and replaced the Seawater Fisheries Act. It applies to all harvesting and other utilisation of wild living marine resources and genetic material derived from them. Its scope is thus wider than that of the Seawater Fisheries Act, and it provides a basis for sound, integrated resource management. All provisions of the Marine Resources Act apply within Norwegian land territory with the exception of Jan Mayen and Svalbard, in the Norwegian territorial sea and internal waters, on the Norwegian continental shelf, and in the areas established under sections 1 and 5 of the Act of 17 December 1976 No. 91 relating to the Economic Zone of Norway.

Section 7, first paragraph, of the Marine Resources Act introduces a principle for the management of wild living marine resources under which the fisheries authorities must regularly evaluate the types of management measures that are necessary to ensure a sustainable management regime. Furthermore, section 19 of the Act provides the authority to establish marine protected areas where harvesting and other forms of use of wild living marine resources are prohibited. However, exemptions may be granted for harvesting activities and other forms of use that will not be in conflict with the purpose of protecting the area.

The management principle of the Marine Resources Act is supplemented by the purpose, management goals and general principles set out in the Nature Management Act. In addition, decisions on priority species and the protection of areas under the Nature Management Act will be among the instruments that can be used in sea areas out to the territorial limit.

Textbox 7.4 Principle for the management of wild living marine resources

The management of wild living marine resources is based on the premise that people should be able to harvest these resources in a way that contributes to food production, employment and settlement. However, it is essential that such harvesting is sustainable and does not cause unacceptable damage to marine ecosystems. Wild living marine resources are to be managed in accordance with the precautionary principle and using an ecosystem approach that takes into account both habitats and biodiversity. This is in accordance with international agreements and guidelines, including the Convention on the Law of the Sea and the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries.

Section 7 of the Marine Resources Act establishes the principle that the fisheries authorities must regularly evaluate the types of management measures that are necessary to ensure sustainable management of wild living marine resources. Thus, the principle requires the fisheries authorities to practise integrated, sound, long-term management of these resources.

Sustainable harvesting in accordance with this management principle entails a greater need for monitoring of sea areas and fish stocks. Up to the present, the fisheries authorities have focused their efforts on monitoring and management of the stocks that are most important in commercial terms. However, the management principle set out in the Act requires the authorities to make regular assessments of all stocks that are harvested, and the effects of harvesting on ecosystems. The management principle therefore entails a major challenge, which the fisheries authorities are now addressing.

Norway’s management of the commercially most important fish stocks is based on extensive research and management advice. In addition, fishermen are required to provide extensive reports to ensure that knowledge of the various harvesting activities is as complete as possible. All catches landed in Norway are registered on landing notes and sales notes. The owner or user of any vessel above a certain size must also keep a catch logbook in which catches are recorded. This means that catches from all stocks and areas are systematically registered, and that the data form part of the basis for advice and management. This information is of fundamental importance for application of the management principle.

Depending on the conclusions of the required regular assessments by the fisheries authorities, it may be necessary to regulate catches by means of quotas, to introduce other types of regulation such as minimum sizes, to close areas to fishing, to restrict the types of gear that may be used or to extend reporting requirements. It is particularly important to take a cautious approach to new harvesting activities, since the knowledge base may be inadequate.

According to the principle for the management of living marine resources, management measures must be evaluated at regular intervals, and must be based on the principle of long-term sustainability and the precautionary principle.

This management principle will be a very important management tool, and is intended to ensure that regulatory measures are adapted to the state of the stocks and that harvesting is sustainable.

The Marine Resources Act also provides the legal authority for regulating the use of marine genetic resources. The provisions on the use of marine genetic resources apply throughout the territorial extent of the Act. Marine bioprospecting has not previously been regulated in Norway. It involves searching for natural products and biochemical resources from marine organisms and subsequent testing of the material with a view to commercial utilisation. Marine bioprospecting is a research and development tool with potential in a number of industrial sectors. The discovery and utilisation of genetic resources can yield considerable financial gains, for example in the pharmaceutical industry, that are based on resources that belong to the community as a whole. Examples include new medicines, flavour-enhancing food and feed additives, nutrients, enzymes and microorganisms used to process food and feed, industrial processes used in the production of textiles, cellulose, biomass/renewable energy, and products and processes used in the oil industry.

Sections 9 and 10 of the Marine Resources Act provide the legal basis for laying down rules for harvesting and investigations and for prescribing that a proportion of the benefits arising out of the use of Norwegian marine genetic material shall accrue to the state. A further assessment will be made of how such rules should be formulated. The development of such rules is important in safeguarding the state’s economic interests and ensuring sound management of these genetic resources. The provisions of the Nature Management Act and the Marine Resources Act on permits for harvesting biological material and sharing of the benefits arising from such activity are very similar.

7.2 Spatial management

Spatial management tools are important in the management of the marine environment and marine resources in Norway. The integrated management plans for Norwegian sea areas consider existing spatial regulatory measures in relation to each other and supplement them as necessary. The management plans themselves are spatial management tools on a large scale. Within each management plan area, a wide range of management tools can be used, ranging from various types of protection (closing areas to harvesting for a limited period of time; using different types of legislation to protect areas permanently; protecting particularly vulnerable and valuable areas; establishing areas with some form of international conservation status, such as world heritage sites; and rules on sustainable use of selected habitat types) to steps such as opening new areas for petroleum activity and establishing routeing and traffic separation schemes for shipping.

7.2.1 Marine protected areas

Norway has adopted the goal of establishing an international network of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in accordance with decisions to achieve this by 2010 under the OSPAR Convention on the protection of the marine environment of the North-East Atlantic and by 2012 under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Protection of selected MPAs under the Nature Management Act or other legislation is an important element of ecosystem-based management, and is intended to play a part in halting the loss of biodiversity, safeguarding the natural resource base and maintaining a representative selection of marine environments as reference areas for research and monitoring. Norway’s network of MPAs will consist of marine protected areas that are included in the marine protection plan and other relevant processes.

In 2001, the Ministry of the Environment, in consultation with the Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy and the Ministry of Trade and Industry, appointed an advisory committee to give advice on areas that could be included in a national marine protection plan and on the appropriate degree of restriction on activities in such areas. In 2004, the committee presented its recommendations on the protection of 36 marine areas for the first phase of the plan.

The next important steps will be to publish notification of the start of the planning process and to obtain information from local interest groups. The areas that will be considered initially are presented in Chapter 10. The municipalities and counties involved will be included in the process so that they can play their role as local and regional planning authorities. After this, an environmental impact assessment for the draft plan will be carried out, and a public consultation process will take place at national level. In accordance with the Government’s policy platform, the integrated management plans will be used as the main tool for managing petroleum activities. For areas more than 12 nautical miles from the baseline, general principles and decisions on the spatial management of petroleum activities are therefore to be set out in the management plans for Norway’s sea areas (see Chapter 10). After the public consultation, the draft plan will be finalised in consultation with relevant directorates and sent to the Ministry of the Environment. Together with other relevant ministries, the Ministry of the Environment will draw up the final proposal for a national marine protection plan. Any adjustments to the draft plan, including the possible removal of some of the areas proposed, can be made at this stage. The protected areas should as far as possible form a coherent network, and the final decision on the plan will be made by the Government (formally by the King in Council). The initial network will be updated, adjusted and supplemented as necessary during the second phase of the work.

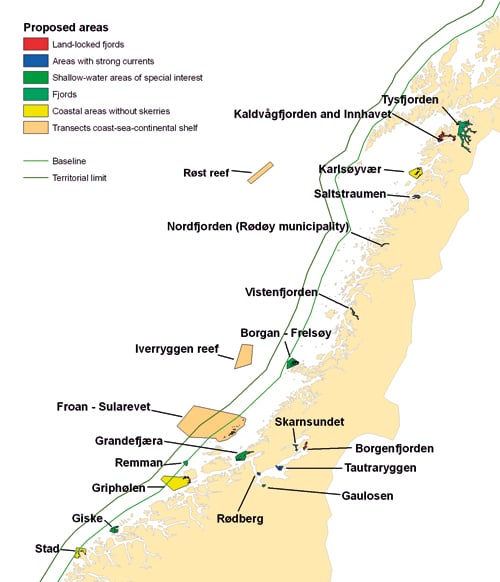

Figure 7-1.EPS Areas of the Norwegian Sea management plan area proposed by its advisory committee for inclusion in the national marine protection plan

Source Directorate for Nature Management

7.2.2 Protection under the fisheries legislation

Under the fisheries legislation, protective measures have been implemented both in the form of prohibitions on fishing in specific areas in annual fisheries regulations and in the form of more permanent restrictions. Several of the annual prohibitions on fishing are extended year after year and in practice represent permanent protection. The Marine Resources Act continues and extends options for establishing marine protected areas as a tool in marine spatial management.

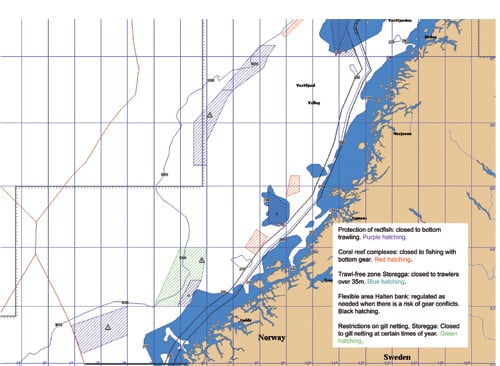

Figure 7-2.EPS Marine spatial management in the fisheries sector in the Norwegian Sea

Source Norwegian Institute of Marine Research

The following are some examples of spatial management by the fisheries authorities in the management plan area:

prohibition against fishing for redfish with trawls in the Norwegian exclusive economic zone north of 62°N;

establishment of «fjord lines», which define areas inside which fishing is restricted to protect coastal cod during the spawning period;

opening and closure of fishing grounds to protect larvae and juvenile fish;

trawl-free zones and flexible areas;

the Marine Resources Act sets out a general duty to exercise special care during fishing operations near known coral reefs. In addition, there is a general prohibition against deliberate damage to coral reefs in all areas under Norwegian jurisdiction.

In addition, there are three specific areas in the management plan area (the Iverryggen, Røst and Sula reefs) where fishing using gear that is towed during fishing and may touch the seabed has been prohibited. This has been done to protect coral reefs against damage from fisheries activities.

7.2.3 Protection under environmental legislation

The Nature Conservation Act provides the legal basis for permanent protection of geographically defined areas against all activities that may have an impact on or damage the environment and natural resources. The Act applies to Norway’s land areas, to lakes and rivers and to the waters out to the 12-nautical-mile territorial limit.

In the Nature Management Act, a separate category of protected area has been retained to make it possible to give permanent or temporary protection to geographically defined sea areas against all activities that may damage or destroy their conservation value. In addition, marine protected areas may be established to safeguard valuable marine areas that are ecologically necessary for terrestrial species.

In addition, the Nature Management Act contains provisions on selected habitat types. The designation of selected habitat types is to be made by the Government (formally by the King in Council). The purpose is to ensure that these habitat types are managed sustainably. The provisions provide guidance for decision makers on the considerations that must be weighed up and the interests that must be safeguarded in managing selected habitat types.

The provisions on the protection of areas and on selected habitat types will apply out to the 12-nautical mile territorial limit. So far, only one purely marine protected area has been established under the Nature Conservation Act (Selligrunnen coral reef, Trondheimsfjorden). This has been temporarily protected as a nature reserve pending a final decision as part of the work on the national marine protection plan. Areas of sea are also included in many other protected areas that have not been established purely for marine protection purposes. These include a number of nature reserves established partly to protect seabirds or marine mammals, and landscape protection areas such as those in coastal areas within the management plan area.

For example, 205 km2 of sea around the Froan archipelago off Sør-Trøndelag has been protected under the Nature Conservation Act to safeguard seals and seabirds. In Nordland and Troms, the protection needs of seabirds and marine mammals in the coastal zone are met through the integrated coastal protection plans adopted in 2002 and 2004 respectively. The coastal protection plan for Nordland includes 74 areas, the three largest of which are around the Helgeland skerries (southern Nordland), the Svellingsflaket area (inner Vestfjorden) and the Røst archipelago.

Protection plans for breeding seabirds in Nord-Trøndelag and Sør-Trøndelag were adopted in 2003 and 2005 respectively, and include a total of 32 areas. A protection plan for breeding seabirds in Møre og Romsdal is being drawn up for adoption in 2009. A protection plan for the Smøla archipelago in Møre og Romsdal was adopted in January 2009, and includes 10 protected areas covering a total area of 270 km2, of which 188 km2 is sea. Remman nature reserve, which includes a large area of undisturbed kelp forest, is particularly relevant to the Norwegian Sea management plan.

The Directorate for Nature Management is holding a public consultation on a proposal to protect Jan Mayen as a nature reserve. The proposed reserve includes the whole island except for the area along the east coast that is already being used for various activities, and a smaller area on the west coast, together with the surrounding territorial sea with the exception of a small area off Båtvika near the buildings on the east coast. The purpose of the proposed nature reserve is to preserve a virtually untouched Arctic island and contiguous areas of sea, including the seabed, with a distinctive landscape, active volcanic systems, a characteristic flora and fauna and many cultural remains. The protection regulations will not prevent the use of permitted harvesting gear in the sea, with the exception of gear for dredging molluscs. The proposal takes into account that it may be necessary to establish infrastructure to fulfil certain functions on Jan Mayen in connection with fisheries activities and if petroleum activities are initiated in the area between Jan Mayen and Iceland.

7.2.4 World heritage sites

The World Heritage Convention does not specify any clear commitments with regard to protection of cultural properties. However, according to Articles 3 and 5, parties to the Convention are obliged to identify and protect their cultural and natural heritage, although the convention says little about legal protection under national law. The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention list the requirements that must be met when a property is nominated for inscription on the World Heritage List. These include «adequate long-term legislative, regulatory, contractual, planning, institutional and/or traditional measures» to protect the property. There must also be a sound management plan or other management regime that safeguards the outstanding universal value of the property and ensures that it is not subject to development or changes that would have a negative impact.

A strict management regime is required for sites that are inscribed on the World Heritage List. Norway has therefore drawn up a management plan for the Vega Archipelago (the only World Heritage Site within the management plan area, see Box 4.4) for the period 2005–2010. Large areas of the seascape are shallow, with high species diversity and substantial biological and commercial resources. The decision to inscribe the property on the World Heritage List recommended that Norway should consider expanding the property to include a buffer zone consisting of islands and sea areas to the north and north-west.

7.2.5 Petroleum activities

While fishing activities are not subject to spatial restrictions unless these are specifically introduced for a particular area, the opposite principle applies to petroleum activities. Petroleum activities are not permitted in an area until the Storting makes a specific decision to open it for this purpose.

The Petroleum Act regulates the management of petroleum resources. It states the basic principle that a long-term approach must be taken to resource management, which will benefit Norwegian society as a whole. Section 3 – 1 of the Act requires that an area must be formally opened for petroleum activities before any activity is started. Proposals to open new areas are put before the Storting. An environmental impact assessment forms part of the basis for any opening process, as described in Chapter 2A of the Regulations relating to petroleum activities.

Acreage for petroleum activities is allocated through licensing rounds for immature areas, which are normally held every other year. In more mature areas, where more is known about the geology and that are closer to existing production infrastructure, blocks are allocated every year through the system of awards in predefined areas (APA). A public consultation has recently been held as part of the basis for an evaluation of the APA system during the first six months of 2009.

The Petroleum Act requires companies to draw up plans for development and operation (PDO) or plans for installation and operation of facilities (PIO) when new fields are developed or pipelines laid. Both types of plan consist of a development/installation part and an impact assessment. A public consultation is held on the impact assessment to ensure that all possible impacts of the project have been adequately assessed. The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy considers the plan and all responses received during the public consultation, and weighs up the different interests and considerations involved. Its conclusions are presented to other relevant ministries. A review of all responses received during the public consultation is published as part of the Ministry’s proposal, which is sent either to the Storting or to the Government for further consideration (all projects with costs exceeding NOK 10 billion must be approved by the Storting). This ensures that the process is fully transparent. Once the Storting or Government has discussed the matter, the project can be approved, subject to any conditions laid down on the basis of their deliberations. Chapter 7 of the Petroleum Act governs liability for pollution damage, and Chapter 8 sets out special rules for compensation to be paid to Norwegian fishermen for any inconvenience arising from petroleum activities.

Parts of the Norwegian Sea have been gradually opened for petroleum activities since 1979. Within the management plan area, further deep-water areas in the Møre and Vøring Basins and western parts of Nordland IV and Nordland V were opened in 1994. The Storting also decided that the eastern parts of Trøndelag I, Nordland IV and Nordland V were not to be opened up for petroleum activities at that stage.

Restrictions on the times of year when seismic surveys and drilling in oil-bearing formations are permitted are other spatial management tools that are used to regulate the petroleum industry. The purpose of such restrictions is to avoid the risk of environmental damage at times when natural resources may be particularly vulnerable, for example during spawning migration or spawning. These are well-established tools, and the restrictions apply to individual production licences.

7.3 Species and stock management

7.3.1 Fisheries management

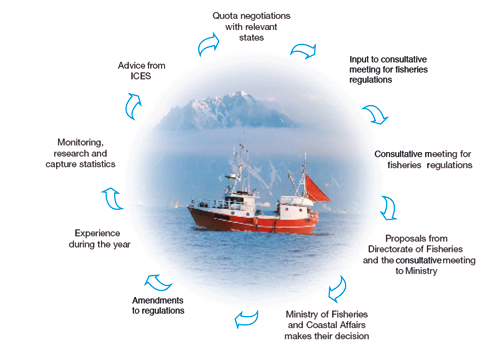

The legal basis for fisheries management used to be the Seawater Fisheries Act, which was replaced by the Marine Resources Act from 1 January 2009. As mentioned previously, the Marine Resources Act introduces a principle for the management of wild living marine resources that involves considerably stricter requirements for ecological documentation. The practical implementation of fisheries management is illustrated by the regulatory cycle.

The regulatory cycle

Most fish stocks are harvested by vessels from several different countries. This means that international negotiations are needed to determine each country’s quotas.

At the beginning of the regulatory year, relevant authorities and organisations meet to give their input to the Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs before terms of reference for the international negotiations are drawn up.

The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) publishes scientific advice that forms the basis for international negotiations.

Negotiations on management measures are conducted with relevant countries, focusing on determining total allowable catches (TACs) for stocks that occur in the exclusive economic zones of several countries or in international waters.

The TACs are then split between the parties through international fisheries negotiations, which take place in October, November and December each year.

The quotas Norway is allocated during the international negotiations form the basis for regulation of the Norwegian fisheries in the subsequent year.

The Directorate of Fisheries draws up proposals for quota regulations which are discussed at a consultative meeting. Ordinary public consultations are held on certain issues. On the basis of these processes, the Directorate sends draft regulations to the Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs, which adopts the quota regulations.

The national quota regulations apply for one calendar year at a time, but may be amended in the course of the year. As far as possible, structural changes in the regulation of a fishery are made during the preparations for the next year’s regulatory measures, but amendments such as changes in quotas, provisions on bycatches, changes in quotas for specific periods, closure of areas, etc., may be made during the year.

Figure 7-3.EPS The regulatory cycle

Source Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs

The overall regulatory cycle is illustrated in Figure 7.3.

In addition to the annual quota regulations, Norway has a number of national and local regulations that are not time-limited. These include provisions on the use of gear, types of gear, mesh sizes, and so on.

Regulation of fishing with bottom gear

The use of all trawls, including bottom trawls, is completely prohibited in areas less than 12 nautical miles from the baseline unless specific exceptions have been made. Any exceptions must be based on an evaluation of the types of management measures that are necessary to ensure sustainable management. Large sea areas outside the 12-nautical-mile limit are also closed to trawling all year round. In addition, further areas are closed at times of year when biological considerations make this necessary, for example if the risk of taking fish below the minimum size or of excessive bycatches is too high.

To protect coral reefs from damage resulting from fisheries activities, the fisheries authorities have also imposed a complete prohibition against deliberate damage to coral reefs in all areas under Norwegian jurisdiction. This means that it is not permitted to use gear that will damage corals near known coral reefs. There is also a requirement to exercise special care during fishing operations near known coral reefs. Five specific coral reef areas are specially protected against fishing with bottom trawls and other gear that is towed along the seabed during fishing.

In accordance with guidelines drawn up by FAO, the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC) has adopted rules to protect specific coral reefs and other vulnerable ecosystems. These prohibit fishing with bottom trawls and other gear that is towed along the seabed. They also apply to other types of gear that can damage the seabed, such as gill nets and longlines.

NEAFC has also decided, in accordance with FAO guidelines, that bottom fisheries in new areas are to be considered as experimental fisheries, and must comply with restrictive rules and reporting requirements. Strict rules for fishing operations and reporting have also been adopted for areas that have been trawled previously, to avoid damage to benthic habitats.

According to these rules, which Norway has implemented for Norwegian vessels, a vessel must always stop fishing if it comes into contact with a possibly vulnerable deep-water habitat. This rule applies not only to corals, but also to other indicators of vulnerable habitats. In such cases, the vessel must change position and report the incident.

These rules will also be made applicable in Norway’s exclusive economic zone, so that the same rules apply to Norwegian fishing vessels regardless of where they are fishing. Using the NEAFC rules as a basis, the Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs has therefore started to draw up similar legislation for Norwegian waters.

Safe seafood

The fisheries authorities are also responsible for the safety of seafood. These responsibilities are met through controls at sea and when catches are landed, organised by the Directorate of Fisheries, and through hygiene and quality controls by the Norwegian Food Safety Authority.

Marine mammals

Norway has traditionally exploited the minke whale stock, and much of the catch is taken in the area covered by the present management plan. The Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) has developed a system called the Revised Management Procedure for calculating catch quotas for all baleen whale stocks. The Norwegian quota is based on this system and set by Norway.

7.3.2 Wildlife management

The Wildlife Act applies to all wild species of terrestrial mammals and to birds including seabirds. According to the Act, wildlife and wildlife habitats must be managed in such a way that ecosystem productivity and species diversity are maintained. Within this framework, wildlife may be harvested in the interests of agriculture and outdoor recreation. During any activity, consideration shall be shown to wildlife species and their eggs, nests and lairs to avoid any unnecessary suffering or injury. All wildlife species are protected unless otherwise provided. Hunting seasons for specific species are set by the Directorate for Nature Management.

7.3.3 Management of endangered and vulnerable species

The loss of marine biodiversity may limit the capacity of the seas to produce food, maintain good water quality and withstand change.

Norway has signed a number of conventions on species protection and management, see Box 2.4. The Convention on Biological Diversity provides the general framework for these efforts, and proposals and decisions on which species should be given special protection are made under the regional and global nature conservation conventions, primarily the Bern, Bonn and CITES Conventions. The environmental authorities cooperate closely with other sectoral authorities on work under these agreements and on their implementation at national level.

Norwegian Red List

The 2006 Norwegian Red List was drawn up by the Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre, and for the first time, it included systematic assessments of marine species. The Red List is drawn up using the criteria developed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The criteria have been developed to make it possible to classify species as realistically as possible according to the risk of global extinction. In 2007, the Norwegian authorities asked ICES to evaluate how suitable the IUCN criteria are for assessment of marine fish species. The need to evaluate the criteria is illustrated by the fact that both sandeels and Norway pout are included on the 2006 Red List, but fishing for both species was permitted in 2008 on the basis of advice from ICES.

Fewer species and populations have been classified as vulnerable or endangered in the marine environment than in fresh water and on land. This may be partly due to the ecological conditions in Norwegian marine areas, where for example many species have larvae that are free-swimming in the water column. There are also relatively few habitat types that combine distinctive qualities with limited extent and distribution. On the other hand, the low proportion of red-listed species in the marine environment may also be due to methodological problems. We have only limited information on species diversity, distribution and population changes for many groups of marine species that are not used commercially. Knowledge of genetic variation within species, for example the existence of local or regional populations, is very limited for both commercial and non-commercial species.

If evidence indicates that a species with a negative population trend is or may be at risk of extinction if the trend continues, it is listed as critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable on a national red list.

The 2006 Norwegian Red List includes 36 species or stocks of marine fish that occur in the management plan area. The European eel and spiny dogfish have been classified as critically endangered (CR), while coastal cod north of 62°N is classified as endangered (EN). Eleven of the red-listed bird species found in the management plan area are associated with marine environments. The common guillemot and lesser black-backed gull (subspecies Larus fuscus fuscus) are considered to be critically endangered (CR), and the Slavonian grebe is endangered (EN). The puffin, kittiwake and Steller’s eider are all considered to be vulnerable (VU).

Ten species of mammals (nine whales and seals and the polar bear) that occur or have occurred in the Norwegian Sea are also included on the Red List. The North Atlantic right whale is the only species that is regionally extinct (RE) in Norwegian waters. The bowhead whale is categorised as critically endangered (CR), the hooded seal as vulnerable (VU) and the blue whale as near threatened (NT).

In addition, Norway has special responsibility for several of the species that occur in the management plan area. The Directorate for Nature Management is drawing up action plans for endangered species of seabirds in Norway.

The fisheries authorities are reviewing which marine species and stocks need to be monitored and managed particularly carefully. Their work is based partly on the 2006 Norwegian Red List. Species that are relevant here include lobster, eel and coastal cod (see Table 7.1).

Table 7.1 Directorate of Fisheries’ plans for monitoring and managing species and stocks in accordance with the management principle set out in the Marine Resources Act. Priority list as of January 2009

| Species/stock | Comments |

|---|---|

| Coastal cod north of 62°N | Working group appointed by Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs, report due at the end of 2009. Wide-ranging measures already implemented, including establishment of «fjord lines». Inside these, only vessels under 15 m using passive gear are permitted to fish cod. |

| Lobster | Stricter regulatory measures introduced in 2008. Important to evaluate their effect after they have been in force for some time. |

| Eel | Working group appointed by Director of Fisheries presented a report with recommendations for measures to improve management on 15 October 2008. Consultation in progress on the report, time limit for comments 15 February 2009. |

| Sandeel | Relatively stationary key species in the North Sea ecosystem. Changeover to spatial management is being evaluated. |

| North Sea cod and coastal cod south of 62°N | Director of Fisheries is evaluating measures for coastal cod south of 62°N on the basis of a report from the Institute of Marine Research. |

| Redfish ( Sebastes marinus and S. mentella) | Year-round prohibition against directed trawl fishery for these species. NEAFC has adopted restrictions on fishing in international waters in the North Atlantic. Close seasons introduced for fishing with conventional gear (coastal fleet). These measures are evaluated annually. |

| Halibut | Stock increasing, especially in the north. North of 62°N, closure in the spawning season (20 December–31 March) for bottom gear (gill nets, trawls, Danish seines, etc.). |

| Blue ling | Introduction of measures being evaluated in 2009. |

| Basking shark | Directed fishery prohibited since 2006. |

| Spiny dogfish | Directed fishery prohibited since 2007, except for coastal vessels under 28 m in length. |

| Porbeagle | Directed fishery prohibited since 2007. |

Source Directorate of Fisheries

7.4 Pollution

Preventing and reducing pollution in the Norwegian Sea and thus ensuring that the marine environment is as pollution-free as possible is an essential basis for maintaining species and habitat diversity and value creation, for example in the fisheries. The key legislation in this field, and an important instrument for achieving these goals, is the Pollution Control Act and appurtenant regulations. The Act lays down a general prohibition against all activities that may entail a risk of pollution, unless exceptions are set out in the Act itself, in regulations or in individual permits. Discharge permits issued to individual enterprises (both land-based industry and the offshore petroleum industry) under the Pollution Control Act set out requirements limiting the quantities of pollutants they may release.

Textbox 7.5 What is BAT?

In 1996, the EU adopted a directive on integrated pollution prevention and control (the IPPC Directive, Directive 96/61/EC, now replaced by Directive 2008/1/EC). The purpose of the directive is to coordinate the regulation of all releases of pollutants to air, water and soil, so that a particular installation needs only one permit, issued by a single authority. This is a way of achieving more integrated evaluation and control of the overall pollution from an installation, and thus better protection of the environment. The Directive has been incorporated into the EEA Agreement. In Norway, existing provisions in the Pollution Control Act had already met most of the requirements of the Directive, but the Pollution Regulations nevertheless include a chapter that implements the requirements more fully.

One important principle introduced in the IPCC Directive was that operators must as a general rule make use of the «best available techniques», or BAT. Emission limits set in a permit must be based on the application of BAT. The European Commission is responsible for obtaining information that can be used to draw up BAT Reference Documents (BREFs), which describe what is considered to be BAT in specific sectors. These are primarily intended for use by national authorities and industry. BREFs are drawn up by the European IPPC Bureau (EIPPCB), which is located within the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre in Seville, with the assistance of technical working groups. A working group including representatives of the authorities and the relevant sector is set up for each BREF.

As a «downstream» country, Norway is to a large extent a recipient of pollutants both from the rest of Europe and from other sea areas. Long-range transport of pollutants with air and ocean currents also has a considerable impact on the Norwegian Sea. Norway has played an active part in the development of a number of international agreements of importance for the marine environment. Requirements to make use of the best available technology (BAT) and best environmental practice (BEP) are important principles in Norwegian pollution legislation, international agreements and EU legislation.

International law relating to chemicals and long-range air pollution is also highly relevant in connection with efforts to maintain the state of the environment in the management plan area. These rules have been considerably strengthened in recent years with the entry into force of several important agreements. Key conventions include the Stockholm Convention, which regulates the twelve most dangerous persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and the Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent (PIC) Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade, both of which entered into force in 2004. The comprehensive new EU chemicals legislation (REACH – Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals) has been incorporated into the EEA Agreement and was implemented in Norwegian law in 2008. Moreover, two new protocols on POPs and heavy metals under the ECE Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution (LRTAP) entered into force in 2003. The Convention on Climate Change, the Kyoto Protocol, and the international agreements on emissions of NOx, SO2 and VOCs are also relevant in this context. The white papers on the Government’s environmental policy and the state of the environment in Norway describe developments in this legislation.

The new Maritime Safety Act, which entered into force in 2007, takes the same approach as the Pollution Control Act and sets out a general prohibition against pollution from ships. It also provides the authority to lay down regulations specifying what is considered to be pollution in this connection. It thus provides the legal authority to regulate releases of organisms from ships with ballast water, and is in line with the International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments (Ballast Water Convention). This was adopted in 2004, and Norway played a key role in its development. The Norwegian Maritime Directorate has recently held a public consultation on draft regulations to implement the Convention in Norwegian law, and these are expected to be adopted in the near future. International law relating to shipping is further described in 7.5.3 below.

7.5 The risk of acute pollution and risk-reduction measures

No human activity can be carried out entirely without a risk of unforeseen incidents. To achieve the Government’s goals as set out in this management plan, it is therefore essential that risk analyses are conducted for commercial activities. The goal is to reduce the risk of adverse impacts on the environment as much as possible, primarily through preventive measures. In addition, the Government considers it important to ensure that there is an emergency response system in place that can prevent adverse environmental impacts in the event of an accident – or if this is not possible, reduce them as far as possible.

7.5.1 General discussion of risk and risk analysis

Risk

Risk identification requires an understanding of possible accident scenarios and their consequences. An understanding of risk is an essential basis for implementing effective measures to prevent accidents and establishing an appropriate emergency response system. In the Norwegian Sea this is particularly important with respect to the petroleum industry and maritime transport. Risk is not static, but changes over time along with factors such as traffic developments, implementation of measures. introduction of new technology, development of new working methods, updating of legislation and follow-up activities initiated by the industry and by the authorities. Historical data and incidents provide important information for an assessment of future developments, but they must not be used uncritically.

All risk-based decisions involve some uncertainty. It is therefore important to be open about the limitations of risk analyses and their results, and to provide information about opportunities for reducing uncertainty, for example by applying the precautionary principle, the cautionary principle or the substitution principle, or through research and development.

Textbox 7.6 Key concepts related to risk

Risk: The risk associated with an activity is a combination of the probability of an event occurring and the consequences of the event. It can be expressed both quantitatively and qualitatively.

Environmental risk: Defined in the same way as risk generally, but only environmental consequences are considered.

The environmental risk associated with an activity is a combination of the probability of an event occurring and the consequences of the event in the form of:

damage to the environment (releases of pollutants, oil spills, etc.) or

loss of/damage to specific resources (populations, species, etc.) and

any secondary consequences resulting from 1 and 2.

Environmental risk = Probability x Consequence

Probability: Likelihood of an event or frequency of spills (recurrence interval).

Consequence: The effects of an event on the natural environment and society. Consequence is the product of the value assigned to a parameter/variable(for example a spawning stock) and the impact of the event on this parameter.

Risk-reduction measures: Measures to reduce the probability or consequences of an accident. Measures to reduce probability (preventive measures) should be given higher priority than measures to reduce consequences.

Source Forum on Environmental Risk Management, ISO Guide 73, and MIRA environmental risk assessment method (Norwegian Oil Industry Association).

Risk analysis and risk management

Risk analysis is an integral part of risk management, and includes both quantitative and qualitative tools. Risk analyses are based on assumptions and evaluations, supported to a varying degree by knowledge, scientific methods, experience and future expectations. A number of recognised accident models have been developed, based on analyses of historical data. They show different mechanisms behind accidents, and it is necessary to recognise that every activity is unique, complex and constantly evolving. This in turn means that one model for risk assessment cannot cover all factors of importance for preventing accidents, and that using several models and approaches is an essential part of risk management.

Understanding how accidents happen is crucial for understanding and managing risk. Risk analysis is a tool for dealing with uncertainty and identifying where risk reduction measures are needed and possible to implement. However, risk analysis cannot determine with any certainty how many accidents will occur in the future, or precisely what their consequences will be. It is therefore essential to know what a risk analysis is based on and communicate this information, and to be aware of the inherent limitations of such analyses. This will clarify what opportunities are available for reducing risk so that activities can be carried out more safely.

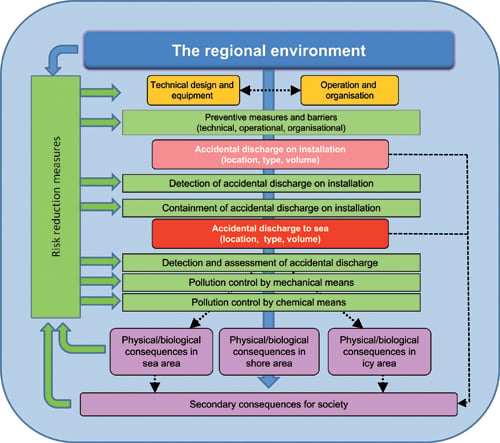

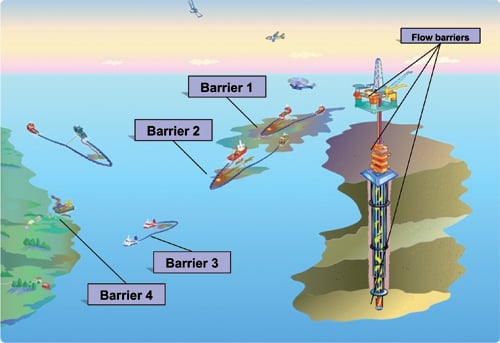

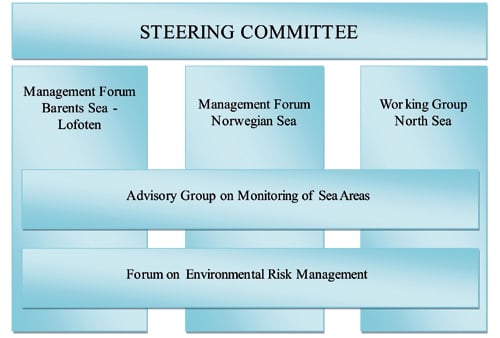

Figure 7-4.EPS Model for integrated environmental risk management drawn up by the Forum on Environmental Risk Management for the Barents Sea–Lofoten area

Source Forum on Environmental Risk Management

Risk management in the management plan area must be based on an integrated model for analysing and managing the risk of acute pollution. The Forum on Environmental Risk Management for the Barents Sea–Lofoten area has developed a general model for integrated management of environmental risk. The model (Figure 7.4) shows where steps can be taken to reduce the risk of acute pollution to the lowest possible level, either through preventive measures or by means of an appropriate emergency response system adapted to the vulnerability of an area and other regional characteristics.

7.5.2 Petroleum activities: legislation and risk management

The oil companies on the Norwegian continental shelf (licensees) have the primary responsibility for preventing and dealing with any acute pollution from their own activities. Comprehensive legislation and control and enforcement procedures have been drawn up to ensure optimal management of the possible impacts of petroleum activities on the environment and of any problems this could cause for other industries.

Textbox 7.7 Responsibilities of the public authorities

The Petroleum Safety Authority Norway is responsible for ensuring compliance with rules relating to technology, operations, organisation and management of petroleum activities to prevent accidents that may lead to oil spills. In addition, the legislation requires companies to take steps to deal with any accidents at source (e.g. using well control equipment) in order to minimise pollution in the event of an unforeseen incident. The Petroleum Safety Authority is also responsible for ensuring compliance with requirements on preventive measures against incidents and accidents that may threaten human life and health and on working environment standards. Such measures often help to prevent spills and other accidents as well.

The Norwegian Pollution Control Authority is responsible for legislation on requirements to report releases of pollutants, remote sensing measurements, analysis and testing of oil and chemicals, testing of emergency response equipment, and emergency response systems for acute pollution. Based on assessment of a specific activity, the Authority may lay down requirements for the emergency response that are additional to those set out in the health, safety and environment (HSE) regulations.

The Petroleum Safety Authority and the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority are jointly responsible for the HSE regulations, and cooperate on processing applications for approval and licences, supervisory activities, development of legislation and so on. There are also cooperation agreements between the Petroleum Safety Authority and the Norwegian Maritime Directorate and between the Authority and the Norwegian Coastal Administration. The agreements facilitate practical cooperation between the private and governmental emergency response systems, and make it easier to deal with conflicts of interest between petroleum activities and shipping. The Norwegian Coastal Administration is the supervisory authority for oil spill response operations run by the petroleum industry.

The Petroleum Act, the Pollution Control Act and the HSE regulations for the oil and gas industry apply from the time when an area is opened for petroleum operations. The HSE regulations were adopted under the Petroleum Act, the Working Environment Act, the Pollution Control Act and the health legislation, and the supervisory authorities are the Petroleum Safety Authority Norway, the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority and the Norwegian Board of Health. A white paper on health, safety and environment in the petroleum industry (Report No. 12 (2005–2006) to the Storting) set out the goal of making the Norwegian petroleum industry a world leader in this field. The petroleum industry is to be at the forefront of developments, with a clear focus on quality, knowledge and constant improvement.

Figure 7-5.EPS Well barriers to reduce the risk of spills (drilling mud, blowout preventer (BOP), redundant valves, open drainage system to collect any oil spilt on the platform), and to limit the release of oil in the event of a spill (emergency response system)

Source Norwegian Oil Industry Association

The HSE regulations are risk-based, which means that safety and emergency response systems must be dimensioned in accordance with the specific risks involved in each activity. This ensures that systems for preventing acute pollution and the oil pollution emergency response system are adapted to the characteristics and location of an activity. Under the regulations, characteristic features of different parts of the management plan area will also have to be taken into account in risk management, for example stricter requirements can be imposed in vulnerable areas. The industry may therefore incur considerably higher costs in connection with activities in vulnerable areas for technological development, both for building knowledge and expertise and in the form of higher operating costs, even if the legislation remains unchanged. Strict regulation and control of the petroleum industry are important in preventing oil spills and minimising their impact.

Furthermore, the HSE regulations build on a general system for assigning responsibility and principles of risk management to ensure sound and responsible operations in all phases of petroleum activities. Licensees, operators and contractors are all responsible for planning and control of risk management in different phases. In addition to the authorities’ inspection and enforcement responsibilities, there is a statutory requirement for the actors in the industry themselves to maintain an internal control system.

The HSE legislation does not generally specify particular solutions, but sets out functional requirements, leaving each actor responsible for developing or using solutions that provide adequate safety standards. The overall goal is for solutions for meeting the functional requirements to be adapted to the specific risks in each case, taking into account the form of organisation and technical solutions chosen, the operations to be carried out, the location of these operations and so on. A key principle is that it must not be possible for one isolated fault or error to result in an accident. This means that more than one barrier must be used to reduce the probability of escalation as a result of an error, hazard or accident, and to limit the damage and nuisance that may result from such situations. The concept of barriers is of key importance in efforts to minimise the risk of oil spills and environmental damage. As a general principle, at least two independent barriers must be used in any situation where there is a risk of oil spills. These may be physical barriers or other measures to reduce the risk of spills or to limit the size of a spill in the event of an accident.

Strict regulation and an effective inspection and enforcement system for petroleum activities are important in preventing acute oil spills and minimising their impact. Risk management is necessary at all stages, from planning to decommissioning, and requires actors to analyse their own activities in detail and to update the analyses if the assumptions on which they are based change. The HSE legislation is therefore an important tool for ensuring that operations meet adequate safety standards in environmentally vulnerable areas as well.

Environmental standards for the petroleum industry, both general requirements and requirements applying to specific installations, are set under the Pollution Control Act, the Petroleum Act and regulations under these acts. Under the Pollution Control Act, operators must hold permits for the use and release of chemicals, injection, and emissions to air. General requirements have also been laid down in connection with the zero-discharge targets for the oil and gas industry. These apply to oil, chemical additives and naturally-occurring substances discharged with produced water.

The emergency response requirements that apply to petroleum activities are discussed in 7.5.4 below.

7.5.3 Shipping: legislation and risk management

Like the petroleum industry, the shipping industry is subject to comprehensive legislation and to control and enforcement procedures to ensure that environmental impacts are dealt with as effectively as possible. The legislation is constantly evolving. In addition, the Government attaches importance to enhancing safety at sea through preventive measures, including both maritime infrastructure and services. The Norwegian Maritime Directorate is an administrative agency under the Ministry of Trade and Industry, and under the Ministry of the Environment in cases concerning pollution from ships and protection of the marine environment. It plays a key role in ensuring maritime safety in a clean environment.

The Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs is responsible for safeguarding Norway’s interests as a coastal state, and does so by promoting maritime transport within safe limits. Preventive measures are the most important aspect of this work. In the event of an accident, an emergency response system with sufficient resources to prevent or limit negative environmental impacts must be in place. The interests of coastal states are important in the development of the international framework in this field. Norway is playing an active part in developing routeing measures to reduce risk, strengthening traffic surveillance and developing new electronic navigation aids and oil pollution emergency response systems.

A white paper on maritime safety and the oil spill response system (Report No. 14 (2004–2005) to the Storting) presented an environmental risk analysis of predicted developments in maritime transport. It also recommended measures to address the challenges that are likely to arise with the expected increase in the volume of maritime transport along the Norwegian coast. The analysis showed that the risk of environmental damage within specified geographical areas will increase in the years ahead unless further preventive and response measures are implemented. The white paper’s recommendations relating to maritime safety and the oil spill response have been or are being followed up. More lessons have been learnt from internal and external evaluations of incidents such as the Rocknes and Serveraccidents, and the Government is focusing on regular evaluations and on introducing new measures when new needs are identified.

International developments

The shipping industry is international in nature. The framework conditions for safe, environmentally sound and efficient transport are therefore largely laid down at international level, and shipping is regulated to a large extent in international law. International rules thus provide an important framework for how Norway can regulate maritime transport in the Norwegian Sea. There is an international trend towards increasingly stringent environmental standards, with Norway playing a leading role. The general requirements relating to ships and crews following from international law apply to all vessels regardless of where they are. Flag states are required to inspect their own ships and ensure that they comply with the rules. Norway also inspects foreign ships that call at Norwegian ports (port state control). 1 The Norwegian Maritime Directorate is responsible for such inspections. Port state control is carried out in accordance with the Paris Memorandum of Understanding of Port State Control (Paris MOU), which applies to 25 coastal states in Europe and Russia and Canada, and requires each country to inspect 25 % of all ships that call at its ports over a three-year period.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is responsible for developing an international regulatory framework for shipping. In the present context, the most important instruments are the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) and the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL).

Since the Erika and Prestige accidents, the EU has adopted three legislative packages to strengthen maritime safety. The third maritime safety package was presented in November 2005, and includes seven key measures to improve the European maritime safety regime. These deal with rules for flag states and classification societies, traffic monitoring in the EU, the port state control regime, and requirements relating to compensation to passengers, shipowners’ liability and accident investigation. In addition, the international legal framework for liability and compensation for damage caused by oil pollution from ships has been considerably strengthened in recent years. New limits for compensation and the establishment of funds also apply to accidents in Norwegian sea areas.

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea lays down the general principle of freedom of navigation outside territorial waters, but also provides for regulation of shipping on the grounds of maritime safety and environmental protection. Under IMO rules, mechanisms have been developed making it possible for coastal states to regulate maritime transport outside their territorial waters, in their exclusive economic zones. Some of the international processes that can be followed to meet special needs are as follows:

A sea area may be classified as a Special Area (SA) under the MARPOL Convention. Stricter rules apply to the discharge of chemicals, oil and waste in an SA. Guidelines have been drawn up for applications for SA status. The North Sea, parts of which are under Norwegian jurisdiction, currently has Special Area status under Annexes 1, 5 and 6 of the Convention (prevention of pollution by oil, prevention of pollution by garbage and SOx emission control).

Establishing routeing systems in areas outside their territorial waters for safety and environmental reasons. Norway has established a traffic separation scheme between Vardø and Røst in North Norway.

Designation of a sea area as a Particularly Sensitive Sea Area (PSSA). These areas are marked as such on international navigation charts. An application for PSSA designation should also include a proposal for protective measures, for example navigational measures such as traffic separation schemes, areas to be avoided and/or reporting requirements. After an evaluation of the question, no Norwegian sea areas are currently designated as PSSAs.

Applications for these designations are assessed separately, and the designations are not mutually exclusive.

Preventive measures – maritime infrastructure and services

Norway is promoting maritime transport within the framework of a sustainable maritime policy. A framework for maritime safety that minimises the risks to people and the environment is an essential basis for sustainable maritime transport. It must include both preventive measures and an emergency response system to deal with any accidents that do happen. Maritime transport is an international industry, and globally applicable rules are in Norway’s interests. The legal framework should therefore preferably be developed by IMO. In Europe, a stronger focus on the interests of coastal states was developed during the 1990s, partly in response to several serious accidents in European waters.

Norway has implemented a comprehensive range of maritime safety measures in its coastal waters by establishing and operating maritime infrastructure and services to reduce the likelihood of incidents and accidents at sea. The maritime infrastructure consists of lighthouses, buoys, signs and the physical improvement of channels to keep them clear and safe. Maritime services include the pilot service, traffic surveillance and control by the Norwegian Coastal Administration’s vessel traffic service centres, electronic navigation aids, charts and notification and information services (information about ice, wave conditions, currents and navigation), and various forms of local regulation, such as restrictions on traffic in the dark and in poor visibility.

There is a growing focus on traffic regulation and surveillance and reporting systems as key accident prevention measures for maritime transport.

SafeSeaNet (SSN) is a European electronic notification and information system for shipping, and is important in terms of both maritime safety and emergency response. Norway has established the system at national level, and is playing an active part in its development in the EU and the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA).

The Long-Range Identification and Tracking (LRIT) system is based on satellite tracking, and has been established as part of IMO’s work on maritime safety and antiterrorism measures. LRIT will be a global system, and is to be operative by summer 2009. According to plan, Norway will be linked to the EU LRIT Data Centre, and will be able to make use of LRIT data in connection with traffic surveillance, for search and rescue purposes, and in connection with environmental and natural resource management.

Regulations on thetraffic separation scheme between Vardø and Røst entered into force on 1 July 2007. They require tankers of all sizes and other cargo ships of 5 000 tonnage and upwards to sail about 30 nautical miles from land. There are two traffic lanes for shipping in opposite directions, and a separation zone between them. The Government is continuing its work with a view to establishing further routeing measures off the coast of Southern and Western Norway.

The Norwegian Coastal Administration’s vessel traffic service centresin Horten, Brevik, Kvitsøy, Fedje and Vardø play a part in preventing hazardous situations and accidents and are an important part of the Coastal Administration’s operative system for oil pollution response. The centres can also use automatic identification system (AIS) data for surveillance of high-risk vessels sailing along the coast. Infrastructure for AIS coverage of Norwegian waters was established along the entire coast out to about 30 nautical miles from land in 2005. AIS data enables the vessel traffic service centres to identify drifting ships and to notify the tugboat service if assistance is needed, even before such ships take contact themselves. It is therefore important to ensure adequate emergency tugboat services. In North Norway, a government service has been established, since the private service is not considered to be adequate. In the management plan area, there is more commercial activity, and the available private tugboat service is considered to be sufficient. Among other things, there are tugboats used in connection with the offshore industry, and these have a duty to provide assistance in emergencies. This system results in more flexible use of the available resources. AIS transmitters and receivers on board vessels combined with other electronic navigation instruments can also reduce the number of ship collisions.

The Norwegian Coastal Administrationworks closely with theNorwegian Defence Forces on surveillance and rapid response to prevent incidents involving vessels from causing acute pollution. The two agencies exchange AIS data and other surveillance data. Naval vessels, particularly Coast Guard vessels, are important for the Coastal Administration in operations to deal with vessel emergencies, both because they can provide tugboat capacity and because they can be used for on-scene command. Many Coast Guard vessels also carry oil spill recovery equipment supplied by the Coastal Administration. If the Coastal Administration is unable to assume immediate command of a recovery and clean-up operation, an agreement between the two agencies ensures that the Defence Forces’ coastal emergency response and on-scene command can take immediate measures on behalf of the Coastal Administration until the latter can take command.

The Coastal Administration and the Norwegian Maritime Directorate have a cooperation agreement on dealing with shipping accidents that entail a risk of acute pollution, whereby the Directorate provides maritime and technical expertise on a round-the-clock basis.

7.5.4 Emergency response system for acute pollution

Organisation and responsibilities

Norway’s emergency response system for acute pollution consists of three parts – private, municipal and governmental services. The Pollution Control Act assigns the main responsibility for maintaining an emergency response system to private enterprises. Emergency response systems must be in reasonable proportion to environmental risk and must be able to deal with acute pollution from the enterprise’s own activities. The Norwegian Pollution Control Authority has set special requirements for enterprises that represent a risk of acute pollution, including petroleum companies, tank farms, refineries, and land-based enterprises that handle environmentally hazardous chemicals.