2 The world in a time of transition

Our world order is changing, and international politics is in a period of transition. The decades following the Cold War were characterised by optimism and a relatively high degree of peace and predictability. The international community was brought more closely together through economic globalisation, freer trade, digitalisation and strengthened intergovernmental cooperation. It was possible to reach agreement in global negotiations on fundamental issues, including human rights, nature, climate and health. The International Criminal Court (ICC) was established. A significant degree of intergovernmental order was the result of a stronger multilateral system in which there was relatively broad agreement to respect international law. The United States was actively engaged in developing this so-called ‘liberal world order’, and Europe and the EU also strengthened themselves as a driving force for this.

However, this did not mean that the world was free of serious wars and conflicts. Europe in the 1990s was strongly affected by the wars in the Balkans. There were genocides in Rwanda and several civil wars in Africa, including in DR Congo. In the 2000s, order and security were threatened by terrorist attacks, such as Al Qaeda’s attack on the United States in 2001, and the subsequent ‘War on Terror’. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, global armed jihadism, ethnic and sectarian conflicts, as well as major popular uprisings during the ‘Arab Spring’, led to upheavals in states and societies in the Middle East and North Africa. There was an increase in terrorism against European countries as well. The ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine and other countries in the region contributed to undermining stability in the Middle East. At the same time, the direct threat to states, and the number of interstate armed conflicts, was at a historically low level. The 1990s and early 2000s were also characterised by the emergence of popular rule and democracy, and many countries experienced positive developments and economic growth.

The end of the Cold War also opened up new room to manoeuvre for Norway. Aided by the reduced tensions between the Great Powers and the relationship of trust between Norway and the United States, we were invited to engage as an impartial facilitator in several conflicts: first in Guatemala, then as facilitator of the back channel between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) that led to the Oslo Accords, followed by involvement in a number of countries such as Sri Lanka, East Timor, the Philippines, Nepal, Sudan and Colombia.

In just a few years, the world situation has changed. We have uncertain international waters ahead of us. Russia’s war in Ukraine constitutes a serious violation of the UN Charter and threatens the European security order.1 We are facing serious threats from Russia, and after decades of peace, a new era has begun for Norway and Europe. This is the most serious security situation for Norway since World War II.2 Many people fear war and conflict in our own region. We are witnessing growing rivalry between global powers, especially China and the United States. Technological development is accelerating in areas such as artificial intelligence and biotechnology, with direct effects on the information space and intergovernmental cooperation. In addition, this has consequences for modern warfare. International trade and the economy are increasingly overridden by national interests. At the same time, the power of multilateral institutions is being weakened, and their legitimacy is being challenged. International law is under pressure, liberal and democratic values are being threatened, and normative policies based on these values are being contested. Great powers and regional powers are increasingly assertive, with the risk that the prohibition on the use of force enshrined in the UN Charter and the principle of state sovereignty may be weakened.

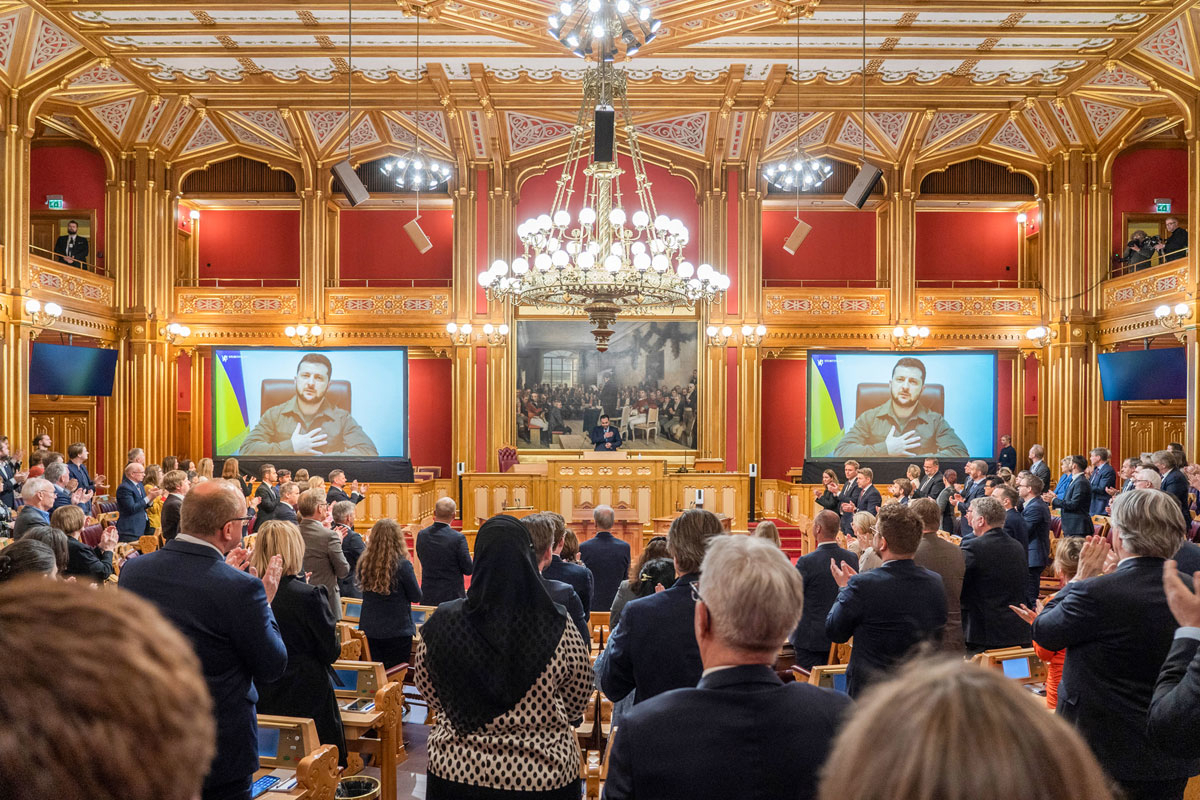

Figure 2.1 Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy addresses the Storting on March 30, 2022.

Photo: Heiko Junge/POOL/NTB

The statistics confirm that the level of conflict in the world has increased since the beginning of the 2020s. Today, we have the highest number of conflicts since the end of World War II. In 2025, there are approximately 60 active conflicts in 35 of the world’s more than 200 states.3 In 2024, one in seven people worldwide was exposed to conflict, and about 130,000 people were killed directly in combat.4 The vast majority of conflicts are civil wars, but in recent years there have also been several interstate conflicts.5 In comparison, in 1993 there were 44 conflicts in the world. All of these were civil wars, and the number of killed was around 45,000.6

Today’s conflicts are becoming increasingly complex, with a larger number of actors, a higher degree of involvement of regional actors and third parties, as well as increased interlinkages between conflicts. This can make it more challenging to find peaceful solutions. The world can be described as one complex theatre of conflict. The Western and Eastern Hemispheres are intertwined, not only through communication, trade, and investment, but also through associations and coalitions across regions. We are witnessing major shifts in US global policy, which may mean that the US is moving away from its role as a stabilising anchor for a global order based on international law. There are also new dynamics in the strategic relationship between Russia and China. The military support from Iran and North Korea has strengthened Russia’s ability to wage war against Ukraine. The conflicts between Israel and Palestine and between Israel and Iran have ramifications for a number of conflicts both inside and outside the Middle East. A conflict situation in one place can affect the balance in other places. One example is how Assad’s fall in Syria was closely linked to Russia’s war against Ukraine and Iran’s weakened influence as a result of the war in Gaza and Lebanon. This also led to changes in the respective positions of Israel, Iran, Turkey, and Russia in the Middle East. We see a similar complexity in the conflict in Sudan, where local conflict lines are amplified and extended through interference from external actors.

There is little to indicate that the trend of increased conflict and tension will abate, at least not in the short term:

-

Russia has violated the basic prerequisites for security in Europe. Although Russia will probably avoid seeking direct conflict with NATO, there is reason to believe that its security and foreign policy goals – and methods for achieving them – may remain incompatible with Norwegian and European interests in the foreseeable future.

-

The international role of the United States is unpredictable and changing, and it is uncertain whether it will once again step up as a champion of a global order based on international law.

-

International institutional cooperation is weakening. We see less willingness among key states to negotiate and stand by binding solutions to war and conflict in the UN Security Council. Multilateral institutions lack funding and the ability to find solutions and deal with humanitarian crises. Flight and migration may increase as a consequence of this.

-

There is a shift in power out and away from Europe and the Atlantic area, with a greater role for China and emerging economies, which are seeking greater international influence.

-

In global disarmament and non-proliferation efforts, there is conflict and a crisis of confidence. In a tense geopolitical situation, deterrence is given greater emphasis.

-

Increasing geopolitical tensions are playing out in new arenas. Competition is increasing for access to critical raw materials and resources, and for global leadership in the development of new technology such as artificial intelligence, satellites and drones. The global economy is characterised by more protectionism, trade wars and uncertainty.

-

Climate challenges are the biggest and most fundamental challenges we face. Nevertheless, the problem is denied in some key circles, and international attention is turned to other issues. Climate change can contribute to higher levels of conflict and struggle for resources, and in many cases migration when population groups have reduced access to water and agricultural areas.

It is symptomatic that the economic costs of war and conflict are increasing. In 2023, global costs were about USD 19.1 trillion.7 At the same time, investments in measures that contribute to peace globally have fallen almost 40 per cent over the past 15 years.8 Western countries are cutting their own aid budgets at the same time as spending on defence and military rearmament is increasing.

War and conflict create or exacerbate key global challenges. Radicalisation, climate change, pandemics, the proliferation of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons, risks related to artificial intelligence and new technology, the blocking of trade routes, increasing prices and changing framework conditions for international trade and investment are examples of cross-border threats that no country can tackle alone. Situations that lead to refugee and migration flows entail major challenges, first and foremost for the people who are fleeing, but also for transit and receiving countries. Such challenges require cooperation across national borders, but it has become more challenging to agree on common solutions.

This helps to bring conflicts closer to us, while events far away can affect us directly more than ever. Norway’s security rests on a global order in which the UN Charter is respected. The same applies to our welfare and economy. Norway is an open economy, and Norwegian export companies and our maritime industry will be affected if markets are negatively affected by instability and conflict. The Government Pension Fund Global is a long-term and universal investor, and the fund’s return is affected by systemic changes and systemic risk as a result of international conflicts.9

International conflict resolution is also changing. Diplomatic and political initiatives to prevent, mitigate or resolve conflicts have not kept pace with the increase in the number of crises. The great powers’ lack of cooperation and declining support for the UN system undermine the ability to prevent and resolve conflicts. Attempts at conflict resolution are increasingly influenced by national interests and dealmaking. Regional powers with different interests are more involved than before in conflicts both within and outside their regions. Sometimes this provides opportunities to achieve solutions to devastating conflicts, but it can also contribute to complicating negotiations. It is increasingly challenging to adequately include women in peace processes. If international law and the ownership of the parties to the conflict and local communities are not taken into account, there is a risk of less inclusive and sustainable political solutions.

Footnotes

Established through the Helsinki Final Act of 1975 and further developed after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 with a more united Europe and EU and NATO expansion.

Office of the Prime Minister (2025). National Security Strategy. Regjeringen.no https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nasjonal-sikkerhetsstrategi/id3099304/

Rustad, S.A. (2025). Conflict Trends: A Global Overview, 1946–2024. PRIO Paper. Oslo: PRIO. Forthcoming 11 June 2025.

Rustad, S.A. (2024). Conflict Trends: A Global Overview, 1946–2023. PRIO Paper. PRIO. https://www.prio.org/publications/14006 and Uppsala University. (n.d.). Uppsala Conflict Data Project (UCDP). accessed 18 May 2025 at https://ucdp.uu.se/

Four interstate conflicts in 2025 from UCDP 2025. These are: Ukraine–Russia, Afghanistan–Pakistan, USA/UK–Yemen and Iran–Israel. PRIO. (2025). Conflict Trends – published June 10, 2025.

Uppsala University. (n.d.). Uppsala Conflict Data Project (UCDP). Accessed 18 May 2025 at https://ucdp.uu.se/

Institute for Economics & Peace. (2024). Global Peace Index 2024. https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/GPI-2024-web.pdf

OECD. (2023). Peace and Official Development Assistance. OECD Development Perspectives, 37. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/peace-and-official-development-assistance_fccfbffc-en.html

Report No. 22 (2023–2024) to the Storting, Government Pension Fund 2024. Ministry of Finance. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-22-20232024/id3033198/