3 Goals and principles of Norway’s chemicals policy

Much has been done to reduce the health and environmental risks associated with hazardous substances, but this is not sufficient to deal with the long-term problems. Ecological toxins are accumulating in the environment and in the food we eat. Ecological toxins that are being released today, even the small quantities each of us leaves behind without stopping to think, will create major problems for our children and grandchildren. Thus, they will be a serious threat to the health of later generations, the environment and future food supplies. The potential consequences are so serious that we must maintain ambitious targets.

Hazardous substances are causing both acute and chronic injury to health and environmental damage today. Several hundred thousand employees in Norway are exposed to harmful chemicals at work, and these may be causal factors in disease. Consumers are also exposed to hazardous substances via the products they buy, and can for example develop serious allergies. The Government will minimise the risks to both health and the environment from releases of and exposure to all types of dangerous chemicals. Norway’s chemicals policy and the action that is to be taken are intended to ensure a high level of protection for consumers and employees, against exposure via the environment, and for the environment.

The Government will

appoint a committee to draw up proposals for how releases of ecological toxins can be eliminated by 2020

determine which substances are covered by the target of eliminating emissions by 2020

eliminate the use and releases of five recently recognised ecological toxins

introduce the target of reducing generation of each type of hazardous waste by 2020 compared with the 2005 level.

3.1 Important principles of Norway’s chemicals policy

The Government bases its chemicals policy on certain key principles to ensure that it is consistent and predictable. These principles provide general guidelines for the Government’s efforts to achieve its goals for hazardous substances. They also provide important guidelines for business and other actors.

Textbox 3.1 Releases of ecological toxins reduced, but problems still exist

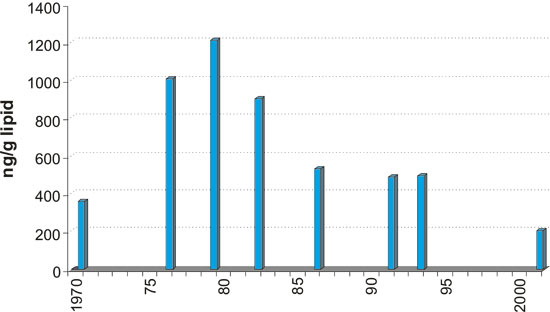

Policies designed to eliminate the use of ecological toxins have given results. Exposure to known ecological toxins is lower than it used to be. Levels of contamination are lower than in the 1970s, both in the environment and in people. For example, the PCB levels measured in breast milk in Norway in the 1990s were much lower than in the late 1970s and early 1980s, see figure 3.1. Dioxin and mercury emissions from industrial sources have been greatly reduced. The offshore petroleum industry was a major source of pollution until the mid-1990s, but has since made deep cuts in its releases of chemicals.

However, ecological toxins are still being released from industrial processes and waste management, and as consumption rises, there are growing numbers of products in circulation. These may contain ecological toxins and other hazardous substances. The international trade regime limits how much individual countries can do by prohibiting products if this is not done through international cooperation.

Precautionary principle

The Government will apply the precautionary principle, which means that if a threat related to hazardous substances is identified during efforts to achieve the goals of chemicals policy, steps must be taken to address this even in the absence of full scientific certainty.

Figure 3.1 PCBs in human breast milk in Norway in the period 1970–2002

Source Norwegian Institute of Public Health

Regulatory measures to reduce or eliminate the use and releases of hazardous substances are based on existing knowledge of their hazardous properties and their possible short- and long-term effects. This knowledge is considered in the context of the standards society has set for the protection of health and the environment. However, the knowledge we have is frequently uncertain. When a specific threat to health or the environment from chemicals is identified, the precautionary principle calls for action to be taken to reduce or eliminate this threat, even if there are uncertainties in the knowledge base. Thus, application of the precautionary principle does not mean that scientific facts are ignored, nor that we fail to make scientific risk assessments. On the contrary, it provides a guideline for the situations where we lack full scientific certainty. Since there is often uncertainty about the risks associated with chemicals, the precautionary principle is particularly relevant in chemicals policy.

Risk management in the workplace

If uncertainty about the level of occupational risk is high, this should normally give grounds for following a precautionary approach. This may for example meaning the use of conservative evaluations and estimates, such as requirements for barriers and robust solutions, or the application of principles such as reducing risk so that it is as low as reasonably practicable (ALARP). If there is insufficient information about what effects a preventive measure may have, the legislation requires further steps to be taken to avoid possible adverse effects.

Textbox 3.2 The precautionary principle and the ozone layer

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer was adopted in 1987 to phase out the use of ozone-depleting substances. At this stage, there was still a high degree of scientific uncertainty surrounding the causes of depletion of the ozone layer. In retrospect, adoption of the Protocol has turned out to be a crucial step in meeting the threats to the ozone layer promptly.

Substitution principle

The Government considers the substitution principle to be a particularly important principle of chemicals policy. The Government expects users of hazardous substances to replace these with alternatives that entail less risk, and that use of the most dangerous substances will as a general rule be discontinued if less hazardous alternatives are available.

Application of the substitution principle means that users of hazardous substances are required to replace dangerous chemicals with other substances that represent less risk to health and the environment, including health at work.

Applying the substitution principle thus helps to support the process of taking new substances and innovative processes into use once they are commercially available. In most cases, a measure introduced to reduce impacts on health, the working environment or the external environment will also have positive effects on the other areas. Nevertheless, there may be cases where it is necessary to weigh effects in different areas against each other.

Polluter-pays principle

One of the fundamental principles of the Government’s chemicals policy is that the costs of pollution, including clean-up costs, must be borne by those who are responsible for the pollution.

Textbox 3.3 Late action results in high costs

A Nordic report, Cost of Late Action – the Case of PCB, estimates that the costs for the EU 25 of remediation of contaminated soil, sediments, etc contaminated with PCBs will be EUR 15 – 75 billion in the period 1971–2018. The study confirms that substantial environmental benefits can be achieved by preventing chemical pollution, and that society incurs large costs by postponing environmental measures.

Thus, the health and environmental costs of the use and releases of hazardous substances must be met by those responsible, so that they bear the full costs of production and marketing of the products involved. It is also important that health and environmental costs are reflected in prices, so that consumers can take them into account when deciding which products to buy.

Prevention is better than remediation

The Government intends to prevent releases of hazardous substances rather than remediating damage, so that we can avoid costly clean-up operations in future. The costs of preventing damage are often moderate compared with those of remediation. This is particularly obvious in the case of ecological toxins, which are very difficult and costly to remove from the environment once they have been released. Preventive measures can do a great deal to reduce or avoid loss of life and injury to health, for example if releases of inflammable or toxic gases are prevented.

Emergency response system for acute pollution

The Government intends to ensure that there is an effective and adequate emergency response system for spills of dangerous chemicals. The emergency response system is based on the a combination of resources provided by industrial enterprises themselves and a public-sector emergency response system. It is important to maintain continual efforts to optimise the system in order to minimise the impacts of any accidents on life, health and the environment.

Life-cycle approach

The Government’s position is that legislation and measures relating to chemicals at different stages of their life cycles should provide support for the efforts to achieve the goals laid down for hazardous substances.

The life-cycle approach means that the entire life cycle is taken into account when the impacts of a product on health and the environment are evaluated. This means that all phases of a product’s life cycle must be evaluated, from raw material extraction, through manufacture, use, transport, and to the end of its life when it has been discarded as waste.

Right to know

In the Government’s view, everyone should be able to find information on which hazardous substances products contain, which chemicals employees are exposed to and what is released to the environment during production processes. The public is entitled to access to information on the effects that the use of chemicals and releases from production processes and products may have on health and the environment. Internationally, the right to environmental information is set out in the Aarhus Convention. In Norway, people’s rights in this field have been extended and strengthened through the Environmental Information Act. The Norwegian Constitution also lays down a right to environmental information. In Norway, people’s right to receive information applies vis-à-vis both public authorities and public and private undertakings. The principle that people have a right to know is also set out in the Product Control Act, the Fire and Explosion Prevention Act and the regulations relating to major accident hazards.

Responsibility of the business sector

The Government intends to give business and industry the responsibility for documenting that products that are placed on the market only contain chemicals that are safe for health and the environment. The business sector is to be responsible for documenting that products are safe for health and the environment, and must also take steps to ensure this if it becomes apparent that products, including those discarded as waste, may pose a threat to health and the environment.

3.2 Goals for hazardous substances

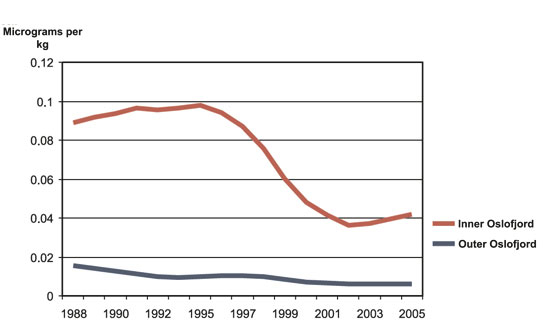

The strategic long-term objective for Norway’s chemicals policy is as follows: Emissions and use of hazardous chemicals will not cause injury to health, harm ecosystems, or damage the productivity of the natural environment and its capacity for self-renewal. Concentrations of the most hazardous chemicals in the environment will be reduced towards background values for naturally occurring substances and close to zero concentrations for man-made synthetic substances. This is a very ambitious goal, given that ecological toxins can persist in the environment for decades or centuries after they are released: see figure 3.2, which shows concentrations of PCBs in mussels. In the Government’s view, this level of ambition is necessary because the long-term threat is so serious.

Figure 3.2 PCB concentrations in mussels from the Oslofjord

Source Norwegian Pollution Control Authority

The Government has proposed a minor amendment to the strategic objective, which now includes the phrase «harm ecosystems». This is also understood to include harm to elements of ecosystems, such as individual species.

Target of eliminating or reducing releases of ecological toxins

Because ecological toxins accumulate in the environment, even small releases can involve an unacceptable health and environmental risk. It is therefore difficult to estimate critical loads for the environment and to find «acceptable» levels of releases of these substances. The Government’s approach is instead to seek to avoid the unmanageable risk that the use and releases of ecological toxins involve. This is reflected in the national target of continually reducing releases and use of substances that pose a serious threat to health or the environment with a view to eliminating them within one generation (by the year 2020). However, some ecological toxins can be formed unintentionally during various processes, and emissions of these substances cannot be completely eliminated. In such cases, the target is to eliminate releases as much as possible. As a first step towards eliminating releases by 2020, the Government has previously adopted the target of eliminating or substantially reducing releases of priority ecological toxins at the latest by 2010. The list of substances to which this target applies is known as the Government’s priority list.

The exact scope of this target, i.e. which substances it applies to, has not previously been specified. It has now decided the substances whose releases are to be eliminated within one generation are those that are included on the priority list. Thus, both targets have the same scope, which will help to reinforce efforts to achieve them and make it clear that efforts to reduce releases of the priority ecological toxins are only the first step towards complete elimination of these releases by 2020.

One complicating factor in eliminating releases of the most hazardous substances within one generation is a lack of information on the properties of most substances, both chemicals that are already on the market and new substances that are being produced in various parts of the world. Some of these and their degradation products may prove to be ecological toxins, so that the target should apply to them as well. To ensure that action is taken when substances are recognised as ecological toxins, it is important that the Government has clear criteria for identifying ecological toxins that should come within the scope of the target.

Textbox 3.4 National targets for hazardous substances

National targets:

Releases of certain ecological toxins (see the priority list in figure 3.4 and the criteria in box 3.5) will be eliminated or substantially reduced by 2000, 2005 or 2010.

Releases and use of substances that pose a serious threat to health or the environment will be continuously reduced with a view to eliminating them within one generation (by the year 2020).

The risk that releases and use of chemicals will cause injury to health or environmental damage will be minimised.

The dispersal of ecological toxins from contaminated soil will be stopped or substantially reduced. Steps to reduce the dispersal of other hazardous substances will be taken on the basis of case-by-case risk assessments.

Contamination of sediments with substances that are hazardous to health or the environment will not give rise to serious pollution problems.

Box 3.5 shows the criteria for identifying substances whose use is to be phased out by 2020. The Government has proposed an adjustment of the criteria that have been used until now. If ecological toxins are found in the environment, it will be sufficient that the levels give rise to concern; it will not be necessary to document a risk to health and the environment. This change is in accordance with the precautionary principle, and will make it possible to include substances as priority ecological toxins at an early stage.

Textbox 3.5 Criteria for identifying priority ecological toxins whose releases are to be substantially reduced by 2010 and eliminated by 2020

Substances that are persistent and bioaccumulative, and that either

have serious long-term health effects, or

show high ecotoxicity

Substances that are very persistent and very bioaccumulative (no requirement for known toxic effects)

Substances found in the food chain in levels that give rise to an equivalent level of concern

Other substances that give rise to an equivalent level of concern, such as endocrine disruptors and heavy metals.

The target of eliminating releases of ecological toxins by 2020 is a very ambitious one. This is not something the environmental authorities can achieve without efforts by all sectors and organisations that are involved. In order to ensure the participation of as many actors as possible, the Government will appoint a committee with representatives from a range of NGOs and other stakeholders to draw up proposals for ways of achieving the target.

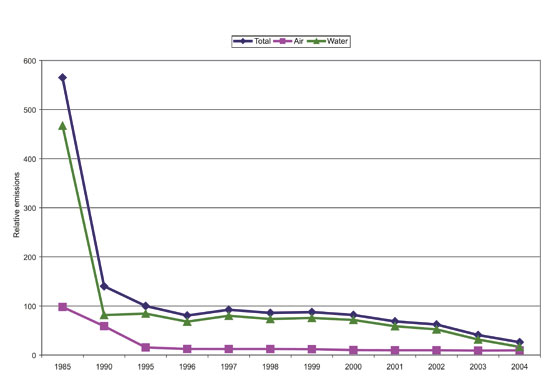

The Government’s list of priority ecological toxins includes 25 specific substances and groups of substances whose releases are to be eliminated or substantially reduced within specified time limits. The term substantial reductions means that releases are to be reduced by 50–90 % from 1995 levels. The time limits are for interim targets, since the use and releases of ecological toxins are to be phased out by 2020 in accordance with the main target. Figure 3.3 shows projected trends in overall releases of all the substances on the priority list.

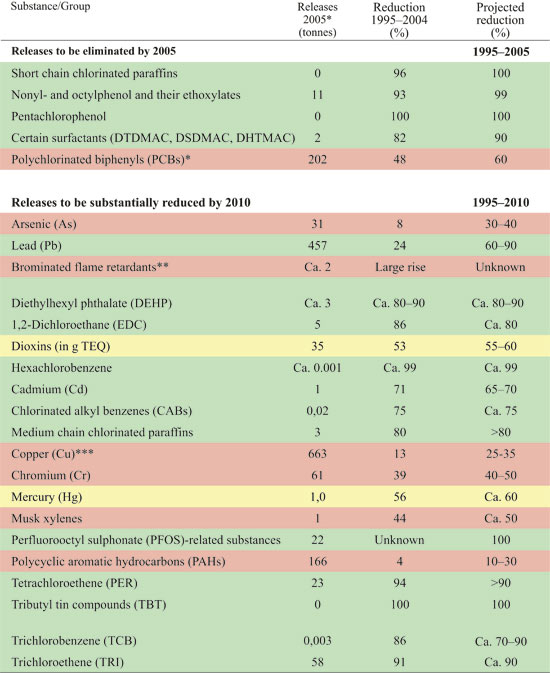

Figure 3.4 shows the latest emission figures for priority ecological toxins, reductions achieved by 2004 and projected reductions up to 2010. Green background shading indicates that the projected releases are in accordance with the target, yellow that it is uncertain whether the target will be achieved, and red that it will not be achieved unless further measures are introduced.

Substantial reductions in emissions have already been achieved for about half the priority ecological toxins, and once planned measures have been implemented, the target of substantial reductions will be achieved for most of the substances on the list. Reductions have mainly been achieved by introducing strict emission limits for industry, regulating products and introducing requirements for waste management. The Government will follow trends in emissions of these substances closely to ensure that they do not increase. The most important elements in this work will be implementation of planned measures, control measures and participation in international efforts to restrict the use of these substances.

Figure 3.3 Index for releases of substances on the priority list. Each substance is weighted according to how dangerous it is for health and the environment. Total releases in 1995=100

Source Norwegian Pollution Control Authority

However, a number of problems remain to be solved. The projections for arsenic, brominated flame retardants, copper, chromium, musk xylenes and PAHs indicate that further measures must be introduced to achieve the required cuts in emissions. Use in products is the most important source of emissions of arsenic, brominated flame retardants, copper and musk xylenes. The most important sources of PAHs are manufacturing, fuelwood use and road traffic. Measures to achieve the targets for these substances are discussed in Chapters 7 and 9.

The environmental authorities will keep the question of which substances meet the criteria for ecological toxins and therefore should be included in the scope of the targets for this group under continual review. New scientific information and changes in patterns of use may make it appropriate to include new substances or remove others from the list.

On the basis of new information and the criteria set out in box 3.5, the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority has identified five new ecological toxins. The Government therefore proposes that the target of eliminating releases within one generation should also apply to the following substances, and that they should be included on the priority list with a view to substantially reducing releases by 2010.

Figure 3.4 Ecological toxins whose releases are to be eliminated or substantially reduced by 2000, 2005 or 2010

* quantity in standing buildings for PCBs

** consumption of brominated flame retardants

*** releases from brake blocks and ammunition not included

Source Norwegian Pollution Control Authority

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)

PFOA has been detected in increasing concentrations in animals, for example polar bears. It has also been detected in low concentrations in human blood. PFOA breaks down very slowly in the environment, and elimination from the human body is very slow. Animal studies indicate that PFOA is reprotoxic. Our knowledge of the main sources of PFOA contamination of the environment is inadequate.

2,4,6 tri-tert-butylphenol

This substance is persistent, very bioaccumulative and toxic to aquatic organisms. No data are available on its presence in the environment. It is used among other things as a lubricating agent.

Dodecylphenol and isomers

This substance is persistent, bioaccumulative and very toxic to aquatic organisms. No data are available on its presence in the environment. It is used among other things as a lubricating agent and in varnishes.

Bisphenol A

Bisphenol A has been detected in sludge, sediments and fish from lake Mjøsa, the Drammenselva river and inner parts of the Drammensfjord, and in sediments, mussels and cod liver from sites along the Norwegian coast.

This substance is not very persistent or bioaccumulative, but is a known endocrine disruptor. It has been shown to act as an endocrine disruptor in fish and snails, and there is concern that it may affect human reproductive capacity. Areas of use include plastic products, paints, glues and electrical and electronic equipment.

Decamethylcyclopentasiloxane (D5)

D5 has been detected in the atmosphere, sewage sludge, sediments and biota. It binds to particulate matter and is highly volatile, with a high potential for long-range environmental transport. It is persistent in water and sediments and is bioaccumulative. It is a suspected carcinogen.

Areas of use for D5 include cleaning products, paints, varnishes and sealing compounds.

Target of reducing the risks associated with other hazardous substances

The target for hazardous substances generally is a substantial reduction of the risk that releases and use of chemicals will cause injury to health or environmental damage. This means that risk reduction measures will be introduced where unacceptable risks are identified. This target applies to most hazardous substances. The level of risk depends on how dangerous a substance is, the quantities that are used and released and the level of exposure of people and animals.

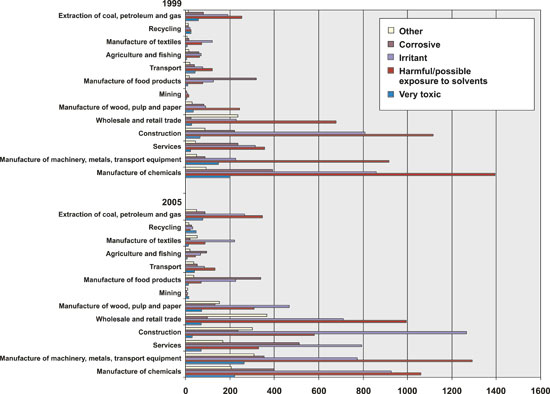

There is no precise measure of the overall level of risk from the use and releases of hazardous substances. However, the number of products in use that contain hazardous substances does give an indication of the risk. Figures from the Product Register, see figure 3.5, show that the number of such products rose from 1999 to 2005. The Government wishes to gain a better picture of the risk by taking account of volumes used and not merely the number of hazardous substances. The aim is to develop an overall risk indicator that reflects progress towards the target directly by showing trends in a way that is clear and easy to understand, and at the same time giving more detailed information on the branches of industry and product groups where hazardous substances are used.

The Government has proposed raising the level of ambition for this target, so that the target is now to minimise the risk of injury to health or environmental damage, rather than to reduce it substantially. This is because even if the level of risk is reduced, it may still be too high if the use and releases of hazardous substances continue to result in unacceptable injury to health or environmental damage. The change also brings the target in line with the global goal of minimising adverse effects on human health and the environment from the use and production of chemicals by 2020, which was adopted at the World Summit for Sustainable Development in Johannesburg in 2002.

Target for clean-up of contaminated soil

The target for efforts to clean up soil that is already contaminated by ecological toxins is to stop or substantially reduce the dispersal of ecological toxins from such areas. Steps to reduce the dispersal of other hazardous substances will be taken on the basis of case-by-case risk assessments. Dispersal of hazardous substances means both runoff to surrounding areas and exposure of people, animals and plants in or growing on contaminated areas.

Clean-up operations have been completed at the 100 most heavily polluted sites in Norway, and the status of the roughly 500 sites in the next category has been clarified. Nevertheless, there are still several thousand sites with contaminated soil in Norway. These must be surveyed and identified, information on them must be made easily accessible to the general public, and where necessary, follow-up action must be taken. Children are particularly vulnerable to contaminated soil, and an action plan for clean-up operations in day care centres and playgrounds where the soil is contaminated is presented in Chapter 10.3.3.

Target for clean-up of contaminated sediments

The Government is continuing to pursue the target that contamination of sediments with substances that are hazardous to health or the environment should not give rise to serious pollution problems.

Figure 3.5 Number of products containing hazardous substances declared to the Product Register in 1999 and 2005, split by branch of industry and danger category.

Source Norwegian Pollution Control Authority

Earlier releases of hazardous substances can be a threat to marine animals and plants. A national committee for contaminated sediments was appointed by the Ministry of the Environment in 2003, and presented a report with its recommendations in June 2006. Pilot projects, research and monitoring programmes have been carried out to increase our knowledge. Proposals for programmes of measures have been drawn up for the 17 most heavily polluted harbours and fjords all round the coast from Hammerfest to the Oslofjord.

The Government’s action plan for contaminated sediments is presented in Chapter 10.2.

National target for hazardous waste

Hazardous waste contains substances that are hazardous to health and the environment, and is a source of releases of such chemicals. Because more and more products contain hazardous substances, the quantity of hazardous waste generated is also rising. Currently, Norway generates almost 1 million tonnes of hazardous waste a year. Most of it is dealt with in an environmentally sound manner, but there is still no information available on disposal or treatment for almost 60 000 tonnes of this waste. Some of this may be disposed of in ways that cause environmental damage.

The current national target is that practically all hazardous waste is to be dealt with in an appropriate way, so that it is either recycled or sufficient treatment capacity is provided within Norway. The Government considers that this does not sufficiently reflect the problems related to hazardous waste, and therefore proposes that the target should instead be to reduce generation of each type of hazardous waste by 2020 compared with the 2005 level. Nevertheless, the Government’s efforts to identify new types of priority hazardous waste may result in a rise in the recorded figures for generation of hazardous waste in the short term.

Figure 3.6 Sediments in many fjords and harbours are contaminated with ecological toxins

Photo: Marianne Otterdahl-Jensen

The general zero-discharge target for the petroleum sector

The general target is that there should be no discharges of environmentally-hazardous substances from petroleum activities. Because of the special problems related to discharges to marine waters, the level of ambition has been high, and this has been instrumental in the development of a high level of protection in the oil and gas sector. There have been substantial reductions in discharges of environmentally hazardous substances in recent years, and further reductions are expected. Discharges of environmentally hazardous substances in connection with production have been reduced by 85 % from 2000 to 2004.

The Government has introduced stricter requirements relating to discharges in the Barents Sea. According to these, operators are required to achieve zero discharges to the sea from petroleum activities during normal operations. The exceptions to this are that drill cuttings from the tophole section may be discharged, and that up to 5 per cent of the annual volume of produced water may be discharged during operational deviations. The Government considers it to be very important to maintain these requirements.

Goals for the working environment

Better knowledge, a stronger regulatory framework and better organisation of workplaces have made it possible to reduce worker exposure to harmful chemicals considerably. Nevertheless, exposure to chemicals is still one of the individual factors that makes the largest contribution to occupational injury and illness and work-related deaths. Figures from Statistics Norway’s surveys of living conditions suggest that about 13 % of the workforce, or about 310 000 employees, are exposed to chemicals in the form of dust, gas or vapour for a large proportion (more than 50 %) of working hours, while about 7 % of the workforce, or about 170 000 employees, are exposed to substances that are irritating to the skin for a large proportion of their working hours. Estimates from the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority indicate that about 3 % of absence due to illness in Norway is a result of exposure to chemicals. Thus, the use of hazardous substances in workplaces is an important cause of exclusion from the labour market.

The Government’s goal is to prevent exposure to hazardous substances at work and in the workplace from causing illness or injury. To this end, the Government will

take steps to obtain better information on occupational exposure to chemicals in Norway

encourage greater awareness of health, safety and environment issues by requiring better risk management in industry and through inspection activities, campaigns directed towards particular target groups, and information

promote a continued research effort in the field of occupational exposure to chemicals and its health effects, both on the continental shelf and in land-based workplaces

pursue the goal of making the Norwegian petroleum industry a world leader and pioneer in the field of health, safety and the environment.

Goals for reduction of the risks associated with the use of pesticides

The agricultural and food safety authorities in Norway have for many years been working actively to reduce the use of pesticides and the risks associated with their use. The action plan for the period 1998–2002 to reduce the risks associated with the use of pesticides was evaluated in 2003. On the basis of an overall assessment of the effects of the measures set out in the action plan, it was concluded that the level of risk to both health and the environment was reduced by at least 25 % during this period. Despite this positive trend, further improvement is needed and possible. Several of the measures in the action plan are long term, and need to be continued to maintain their effects. An updated action plan was therefore adopted for the period 2004–08. It sets out goals and measures for the use of pesticides.

The action plan lays down the following goals:

to make Norwegian agriculture less dependent on chemical pesticides

to reduce the risk of damage to health and the environment associated with the use of pesticides by 25 % in the period 2004–08, which would give a total reduction of 50 % in the period 1998–2008.

levels of pesticides in food and drinking water are to be minimised and not exceed limit values

pesticides should not be present in groundwater and levels should not exceed limit values for drinking water

levels of pesticides in streams and surface water are to be minimised and not exceed values that might result in environmental damage.