4 A world where there is less risk from chemicals

Norway will call for and play a leading role in ensuring stricter international regulation of hazardous substances. The Government would like to see global prohibitions against the use of more of the substances it considers to be ecological toxins and will propose new substances for inclusion in appropriate international agreements. Norway will work actively towards a legally binding global instrument to reduce releases of mercury and other heavy metals. Hazardous substances will be a priority area of development cooperation policy, and efforts in this field will gradually be expanded.

The Government will

work towards a global instrument that strictly regulates the use and releases of mercury and other heavy metals, and help to finance the international negotiations on such an instrument

work towards strict regulation of more substances under the international agreements on persistent organic pollutants (POPs). This includes global regulation of endosulfan and hexabromocyclododecane (HBCDD)

work towards stricter emission limits on POPs and heavy metals in the ECE area in connection with the revision of the protocols under the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (LRTAP Convention)

play a part in obtaining more information on the Arctic as a barometer of global chemical pollution and in using this knowledge actively to achieve stricter regulation of substances categorised as ecological toxins, for example by documenting their presence in the Arctic, the sources of pollution, and its effects

play a part in making the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) an effective tool for minimising the global harmful effects of dangerous chemicals by 2020

play a leading role in the development and adoption of a new convention on ship recycling under IMO, with a view to providing a sound international framework to reduce the use of hazardous chemicals in the construction of ships and on board ships and to ensure that hazardous waste is dealt with appropriately

work towards the introduction of the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals at the earliest possible date both in Norway and in other countries

give priority to and increase funding for work on hazardous substances in development cooperation, both multilaterally and bilaterally, and assist developing countries in building up sufficient capacity to deal with dangerous chemicals and hazardous waste.

Figure 4.1 Long-range transboundary pollution affects top predators like these killer whales

Photo: John Stenersen

4.1 Dangerous chemicals are a global problem

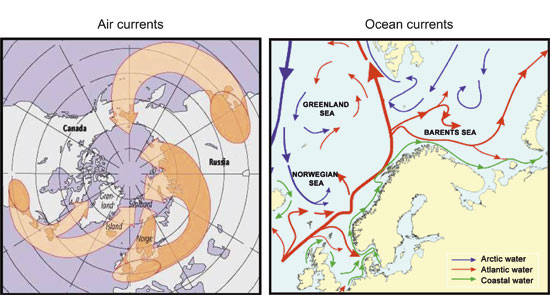

Pollution does not stop at national borders. Air and ocean currents transport ecological toxins across borders and over long distances, particularly towards the Arctic, see figure 4.2. As a result, the pollution load is heavier in the Arctic than would be expected given its remoteness from population centres and more heavily polluted areas. This particularly affects animals at the top of food chains, the top predators such as polar bears, glaucous gulls and killer whales. Population groups whose diet includes a substantial proportion of marine mammals and seabirds are also vulnerable. There is good documentation that the Arctic is polluted by both POPs and heavy metals. And pollutants are transported far afield. For example, mercury inputs to the Norwegian environment from sources outside Norway are more than twice as high as total Norwegian releases. The proportion of long-range pollution is even higher for heavy metals such as lead and cadmium. It is thus clear that releases of these substances can only be eliminated by means of international solutions.

Figure 4.2 Air and ocean currents transport ecological toxins towards the Arctic

Source Norwegian Institute for Air Research and Institute of Marine Research

At present, the OECD countries account for about 75 per cent of global chemical production. Global production is expected to increase, and the OECD’s share is projected to drop to 63 per cent by 2030. This means that more chemical production will be taking place in developing countries, where pollution control is less effective.

International trade in products also involves the transport of hazardous substances, so that releases of these substances may occur far away from the production site, when products are used or discarded as waste. Imports account for a large proportion of the products used in Norway. Relatively few products are produced in Norway or specifically for the Norwegian market. The international trade regime limits how much individual countries can restrict or prohibit products, making international regulation even more important.

The world community has recognised that the use and release of hazardous substances is not in accordance with sustainable development. The UN summit in Johannesburg in 2002 therefore adopted a new goal of minimising adverse effects on human health and the environment from the use and production of chemicals by 2020.

4.2 New international solutions and initiatives

A number of international agreements on dangerous chemicals and hazardous waste have been adopted to deal with these global problems. The Government considers it important to ensure that these agreements reinforce each other. Norway is therefore advocating closer cooperation between the international agreements on dangerous chemicals (POPs and heavy metals) and on hazardous waste. In addition, the Government will work towards stricter global regulation of the most dangerous chemicals.

New global agreement on mercury?

In the Government’s view, strict global controls should be introduced on the use and releases of mercury. A number of substances are already prohibited under the global Stockholm Convention, but this only applies to persistent organic pollutants, not to metals. The Government will therefore work towards a legally binding global instrument on mercury. This should allow for the inclusion of other substances such as lead and cadmium, on the pattern of the Stockholm Convention. On Norway’s initiative, Nordic cooperation has been established to continue work on this.

Textbox 4.1 Children and fetuses particularly susceptible to mercury exposure

Studies on the Faroe Islands have showed that a high dietary intake of mercury can cause fetal damage. Whale meat, which contains high levels of organic mercury compounds (methylmercury), is a normal part of the diet on the Faroe Islands, and some children were found to have learning difficulties related to damage to the nervous system. This is interpreted as being a result of exposure of fetuses to high levels of mercury.

Studies in the US have shown that one in six women of childbearing age have blood mercury levels that are high enough to cause adverse effects on fetal development.

Mercury is an extremely dangerous pollutant and currently represents a threat to the environment and human health both in Norway and globally. The nervous system of fetuses and children is particularly vulnerable to mercury damage, see box 4.1. Mercury is an element and therefore not degradable. Organic mercury compounds, which form when mercury has been released into the environment, accumulate in food chains and end up on our own plates, particularly in fish. In Norway, nationwide advisories to limit the consumption of large predatory freshwater fish have been issued because of high levels of mercury. Mercury is as serious a global problem as the most dangerous POPs such as PCBs, dioxins and brominated flame retardants. The mercury pollution load in the Arctic is increasing as a result of long-range transport, and now poses a threat to health and the environment.

Global efforts to phase out more POPs and heavy metals

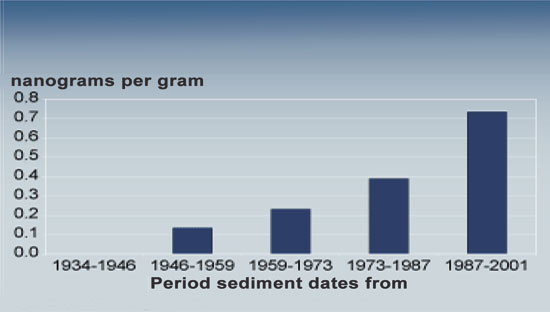

The Government is working towards expansion of the scope of the Stockholm Convention, so that more substances are covered by a global prohibition. Norway has already proposed that the Convention and the POPs Protocol under the LRTAP Convention should include one brominated flame retardant (penta-BDE) on their lists of banned substances. Very high levels of penta-BDE have been found in some samples, including fish from Lake Mjøsa in Norway. Norway will also ensure that proposals are made for the inclusion of endosulfan and HBCDD in the Convention. Endosulfan is a widely used pesticide and causes serious injuries to health in developing countries. HBCDD is a brominated flame retardant that is widely used in industrial products throughout the world, among other things in textiles and electronic products. Analyses of seabird eggs from North Norway have shown that seabirds have been exposed to rising quantities of these substances in the past 20 years. In 2006, Nordic cooperation was established on Norway’s initiative to draw up proposals for the inclusion of further substances in these agreements.

Textbox 4.2 Sheila Watt-Cloutier and her fight against POPs

Levels of several POPs and mercury are very high in the Inuit people of Canada, Greenland and Russia. High levels of these pollutants have been found in the blood of pregnant women and in breast milk. Pollution levels in the mother’s blood are a good indication of the fetal exposure, and levels in breast milk give a clear indication of exposure after birth.

Sheila Watt-Cloutier has been chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Conference (ICC) for several years. Her work focuses particularly on the special problems that long-range transport of POPs and other pollutants and climate change are causing for Arctic indigenous peoples. She received the Sophie Prize for environment and sustainable development in 2005 in recognition of her work.

In the Government’s view, the provisions of the POPs and Heavy Metals Protocols under the LRTAP Convention should be made more stringent. More product groups should be regulated under the Heavy Metals Protocol, particularly products containing mercury.

A global strategy for dealing with dangerous chemicals

It is unlikely that the problems associated with the use and releases of dangerous chemicals could be dealt with through measures in the environmental sector alone. Efforts will also be required in other sectors, for example, the health, working environment, development cooperation and agricultural sectors. The development of the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) and its adoption in February 2006 is part of an integrated approach to dealing with these problems. The Government will play a part in making the SAICM becomes an effective overall framework for activities to improve control of the use of dangerous chemicals internationally. Norway was one of the countries that took the initiative for development of the strategy, and has contributed funding to the process through a bilateral agreement with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). In addition, Norway has provided substantial funding to support activities in developing countries, see section 4.3.

Textbox 4.3 The most important international agreements on chemicals

Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants

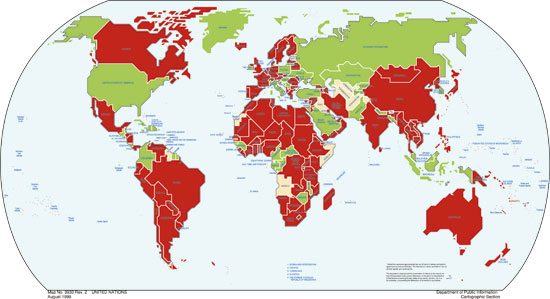

The Stockholm Convention is the most important agreement regulating POPs at global level. The Nordic countries played a leading role in its establishment. More than 130 countries have ratified the convention since it was signed in 2001, including large, important countries like India and China, see figure 4.3. It currently applies to the 12 substances and groups of substances that are considered to be most dangerous, including PCBs, DDT and dioxins. It prohibits continued use of most of these substances.

Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent (PIC) Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade

This convention was established to prevent chemical products that have been banned in industrialised countries from being dumped in developing countries. Developing countries must give prior consent to the import of dangerous substances, which are listed. The Government intends to take active steps to provide notification of substances whose use is prohibited in Norway, and supports the inclusion of as many substances as possible in the list. It is particularly important to ensure that all types of asbestos are included in the list.

Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal

The Basel Convention was established to avoid dumping of hazardous waste in developing countries. Its purpose is to minimise waste generation and ensure environmentally sound disposal of hazardous waste. The Government is working towards the inclusion of a binding target for the reduction of quantities of hazardous waste in the convention. Norway is also working actively towards the establishment of an integrated global regime for the management of waste from ships.

Protocols under the LRTAP Convention

Protocols dealing with heavy metals and POPs have been adopted under the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution (LRTAP Convention). The Heavy Metals Protocol requires the parties to reduce their total annual emissions of cadmium, lead and mercury to the atmosphere to 1990 levels. These agreements are important for reduction of Europe’s total emissions, and therefore for reduction of long-range transport of these pollutants to Norway and the Arctic.

A new convention on ship recycling

At present, 90 per cent of all ship breaking takes place in countries in Asia, and the market is dominated by India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and China. Ships that are to be scrapped often contain hazardous waste, including dangerous POPs such as PCBs, heavy metals, TBT (an anti-fouling agent) and asbestos. At present, there are inadequate controls on these chemicals during the ship breaking process. The Government will therefore work towards considerably stricter international rules on controls to ensure safe and environmentally sound recycling of ships. A Norwegian draft text for a convention was presented to IMO in March 2006, and is being used as a basis for further development of the convention. It is essential that a system is developed that requires environmental considerations to be taken into account throughout the lifetime of a ship, particularly in order to reduce the use of dangerous substances in ship construction and on board ships, and to ensure sound management of recycling operations.

Figure 4.3 Countries that had signed (green) and ratified (red) the Stockholm Convention as of September 2006

Source UNEP

The draft text proposes that ship-breaking yards must be approved before they can accept ships, and that ships may only be delivered to approved facilities. It also proposes rules to prohibit or reduce the use of dangerous substances, and a requirement to maintain lists of which dangerous substances a ship contains. These are to be enforced through a system for issuing certificates and through control of ships. A reporting system for ships destined for scrapping is proposed to ensure control of where they are delivered, and requirements for recycling plans will be drawn up. The Government intends Norway to play a leading role in the work of developing a global convention, to adopted by 2009 at the latest.

The Arctic as a barometer of global pollution

The bioaccumulation of POPs and heavy metals in food chains in the Arctic is giving cause for concern. Levels of substances such as PCBs and mercury in both people and animals are alarmingly high in several parts of the region, and levels of recently detected ecological toxins are rising.

Figure 4.4 Persistent organic pollutants accumulate in food chains. Puffin photographed in the Lofoten Islands.

Photo: John Stenersen

Even though there are local sources of POPs and other ecological toxins in certain parts of the Arctic, inputs from long-range transport are dominant. This is particularly true of substances whose hazardous properties have recently been recognised. Because there are few local sources of any significance, levels of these substances in the Arctic environment act as a barometer of their global transport and spread. The Government views the Arctic as a suitable area for registering the presence of new long-range pollutants and for monitoring pollution trends over time after regulation of the use of dangerous substances.

The Government will build up more knowledge about the Arctic as a barometer of global pollution, and will use this knowledge actively to achieve stricter international regulation of ecological toxins. Better documentation of levels of these substances in the Arctic and their effects will therefore be necessary.

Textbox 4.4 Nordic strategy to deal with environmental pollutants in the Arctic

A Nordic strategy for the Arctic climate and environmental pollutants was adopted at the meeting of Nordic environment ministers in Copenhagen in March 2006. According to the strategy, the Nordic countries will work together to obtain and disseminate more information on the presence and effects of environmental pollutants in the Arctic environment, with a view to reducing global releases of such substances.

The white paper on Norway’s integrated management plan for the Barents Sea–Lofoten area (Report No. 8 (2005–2006) to the Storting) proposed an integrated system for monitoring the state of the marine environment, which is to include monitoring of POPs and other ecological toxins. The white paper also proposed the establishment of an advisory group on monitoring of the Barents Sea, headed by the Institute of Marine Research, to be responsible for coordinating environmental monitoring in this region and making the results available. This group was established in autumn 2006, and monitoring of ecological toxins will be expanded from 2007. This will make an important contribution to documentation of the state of the environment in the Arctic and thus to efforts to gain international acceptance of the need to reduce global emissions of these substances.

Textbox 4.5 New ecological toxins in the Arctic

PFOS and other perfluoroalkyl substances have been found in samples taken from glaucous gulls and polar bears in the Arctic. The levels of certain brominated flame retardants in sediments in the Arctic are rising. In a study carried out in 2005, these substances were found in eggs of glaucous gulls, herring gulls, common guillemots, kittiwakes and puffins in Norwegian parts of the Arctic. Brominated flame retardants are used in many different products, but releases do not generally originate from the Arctic. Both PFOS and brominated flame retardants have also been found in the blood of women from North Norway and Siberia. High levels of POPs such as PCBs and DDT have previously been found in animals and people in the Arctic. Little is known about how the total load of such substances affects people and animals over time. In humans, fetuses and young children are particularly susceptible.

Figure 4.5 Levels of brominated flame retardants in sediment cores from Bjørnøya

Source Norwegian Pollution Control Authority

UNECE Convention on the Transboundary Effects of Industrial Accidents

Parties to this convention are required to apply preventive, preparedness and response measures to deal with industrial accidents with transboundary effects. Norway has ratified the convention, and has undertaken to provide financial support for some of the work under the convention. The Government will give priority to this in the years ahead.

4.3 Environmental development cooperation as a tool for reducing releases of hazardous substances

It is important to use development cooperation as a tool for reducing releases of hazardous substances, both because it is poor people who are most severely affected by pollution and because controlling releases of hazardous substances is an essential basis for sustainable development in developing countries. Moreover, Norway has also commited itself to such efforts under international agreements. The Government will give priority to efforts to deal with hazardous substances in development cooperation, and has identified hazardous substances as a thematic priority in the Norwegian action plan for environment in development cooperation.

Chemical products account for almost 10 % of world trade. The OECD has estimated that global production of chemicals will almost double by 2020. Production is likely to grow most rapidly in developing countries. However, these countries are lagging far behind OECD countries in the control and management of chemicals. Unless the growth in production is accompanied by greater efforts to improve chemical management systems, economic growth may not result in improvements in welfare.

As a result of inadequate inspection and enforcement systems for chemicals, local enterprises can contaminate neighbouring areas and pollute water, air and soils. Poor people are hardest hit by exposure to ecological toxins through the food they eat, hazardous waste disposed of locally, industrial emissions, and the use of products, including pesticides. Chronic diseases, some caused by dangerous chemicals, are a growing problem, and according to the World Health Organization, by 2020 they may have a greater effect on public health in developing countries than infectious diseases. Children are particularly vulnerable. For example, studies from India show that most victims of poisoning are children under five years old. Dangerous chemicals are also transferred to the fetus during pregnancy and to infants through breast milk, and can cause permanent damage. In the Africa Environment Outlook for 2006, UNEP states that failure to develop regional and national chemicals management systems will hinder development in Africa.

Inadequate controls on the use of pesticides and the content of chemicals in products, and high releases of pollutants from the expanding industrial sector in developing countries such as Asia’s growing economies, make developing countries particularly vulnerable to hazardous pollutants. Developing countries must protect water resources against chemical pollution so that they do not become dependent on costly water purification technology. Integrated river basin management, and especially the protection of wetlands that function as biological purification systems, are important in this context.

Textbox 4.6 Use of mercury in gold mining

The use of mercury in small-scale gold mining is a particularly high-risk activity, since children and adults often work with mercury without any protection. According to UN (UNIDO) figures, about 6 million people throughout the world (Asia, Africa and South America) are engaged in small-scale gold mining. This number is likely to rise.

Figure 4.6 Small-scale gold mining

Source UNIDO

Releases of hazardous substances can make the population more sceptical to industrial activities. Poor chemicals management can also prevent developing countries from gaining access to international markets for their products. For example, international requirements for food safety require systems for regulating the use of chemicals in food production and for monitoring food. Vietnam has for instance been seeking to halt the use of dangerous pesticides because residues of pesticides in Vietnamese products were making them unsuitable for international trade. This is also a major problem in other parts of the world, such as Africa.

When ecological toxins are released, the pollution they cause is regional rather than purely local. Many of these substances, such as the POPs regulated by the Stockholm Convention, spread throughout the world once they are released. In addition, dangerous chemicals are spread through trade in products. But even in cases where releases of pollutants spread across national borders, the pollutant load is highest near the source. Measures to reduce pollution or the use of dangerous chemicals thus have positive effects both in the country where they are implemented and in a wider region, and in many cases globally.

It is a prerequisite for increased development assistance that developing countries are able to assess and set priorities for chemicals-related measures and to develop plans or other means of building up a framework and sufficient capacity for chemicals management. The Quick Start Programme under the SAICM is intended to put developing countries in a position to determine their priorities. In 2006, the Government therefore undertook to provide NOK 25 million over a five-year period to support the Quick Start Programme.

Norway’s chemicals-related development assistance will focus on assistance in the field of pollution control, including hazardous waste. In addition, issues and measures in several other fields are relevant to chemicals, for example:

health issues (acute and chronic diseases linked to chemicals)

agricultural issues (pesticides, food safety in developing countries)

fisheries (presence of POPs and heavy metals in fish)

working environment issues (exposure to chemicals in the workplace, child labour)

industry, technological developments (may in addition promote more sustainable industry)

water resource management (water pollution, preventive measures, water purification).

The main channels for efforts related to ecological toxins will be UNEP, the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The work of the Global Environment Facility (GEF) is also very important. At country level, coordination through UNDP is essential. It is also important to support the programmes for competence and capacity building under the global chemicals conventions. These are designed to help developing countries to implement their obligations under the conventions.

The Government will increase assistance in the field of chemicals, and intends Norway to contribute to:

competence and capacity development in the field of chemicals to put partner countries in a better position to implement their international commitments and the SAICM

development of national legislation and effective enforcement in partner countries

cooperation with and support for sectors that use and release ecological toxins with serious adverse effects, including clean-up measures for industries that have negative impacts on health and the environment.

The Government will continue cooperation to reduce releases of POPs and heavy metals from Russian industry and waste disposal sites, both through bilateral cooperation programmes and through projects under the auspices of the Arctic Council.

4.4 New global system for classifying and labelling of dangerous chemicals

In 2003, the UN adopted the new Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS), which applies to all use and handling of hazardous chemicals, and lays down rules for classifying chemicals according to the physical, chemical, health and environmental hazards they present. The GHS also contains provisions on the labelling of dangerous chemicals, and provides guidance on drawing up the safety data sheets that are required to accompany such chemicals. Harmonised international rules for the transport of dangerous goods have been in existence for some years. The adoption of the GHS means that there is a uniform system for classification of chemicals both during transport and in all other contexts.

The purpose of the GHS is to ensure that information on the hazardous properties of chemicals is provided so that health and the environment can be protected through appropriate use, and at the same time to facilitate global trade in chemicals. The GHS is an important tool for increasing knowledge of the hazardous properties of chemicals and ensuring that they are handled as safely as possible throughout the world. It can also help to reduce the extent to which hazardous substances are used in products, and to avoid their dispersal in the environment. Norway has played an important role in development of the GHS, especially the rules for classification and labelling of carcinogenic substances. This has helped to bring about a result that will maintain the level of protection already provided by current Norwegian legislation.

All countries have been urged to introduce the GHS as soon as possible, and the UN hopes it will be fully implemented throughout the world in 2008.

The Government will work towards the introduction of the GHS both in relevant Norwegian legislation and internationally, and will support its introduction and effective use in developing countries. The EU will introduce the GHS in its new consolidated legislation for classification and labelling of dangerous chemicals, and the rules for safety data sheets will be incorporated into REACH. Thus, the development of the global GHS will have direct consequences for the legislation Norway introduces under the EEA Agreement.

The Government will give priority to the work of the GHS Sub-Committee on further development of the GHS, both because it will provide better protection for health and the environment worldwide, and because it will be of crucial importance for EU/EEA legislation.