8 A safe working environment

The Government’s objective is to promote an inclusive working life where due account is taken of both mental and physical aspects of worker health.

The Government will therefore establish a framework that provides workers with effective protection against the harmful effects of chemicals in the workplace. To achieve this, knowledge about the harmful properties of chemicals must be developed and disseminated. Furthermore, individual enterprises must take chemical health hazards seriously; they must carry out systematic surveys and risk assessments of relevant chemical health hazards and implement appropriate preventive measures.

8.1 The extent and health effects of occupational exposure to chemicals in Norway

Figures from Statistics Norway’s survey of living conditions from 2003 suggest that 13 % of the workforce, or about 310 000 employees, are exposed to harmful substances in the form of dust, gas or vapour for a large proportion (more than 50 %) of their working hours, and about 7 % of the workforce, or about 170 000 employees, are exposed to substances that are irritating to the skin for a large proportion of their working hours. In addition, many workers are exposed to chemicals for less than 50 per cent of their working hours. In 1998, the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority estimated that 3 % of absence due to illness in Norway was a result of exposure to chemicals. It was also calculated that absence due to illness and exclusion from the labour market as a result of exposure to chemicals were reducing wealth creation in Norway by around NOK 3.5 billion per year. Hospitalisation costs linked to this problem were calculated at NOK 54 million per year. Besides being an important cause of exclusion from the labour market, exposure to chemicals often affects the health of workers in ways that reduce their quality of life substantially. On a general basis, it can be stated that a substantial proportion of the health injuries in the Norwegian population that are directly related to chemicals are a result of occupational exposure.

According to a report issued by the National Institute of Occupational Health in 2005, international scientific research indicates that approximately 15 % of all cases of asthma, chronic obstructive lung disease (COLD) and lung cancer in men can be linked to the working environment. In Norway, the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority estimates that 700–800 persons die every year of cancer or COLD caused by exposure to chemicals at work. Respiratory complaints are the third most common cause of absence due to illness and exclusion from the labour market, after musculoskeletal disorders and mental illness, and the Labour Inspection Authority estimates that at least 20 % of these respiratory complaints are occupational diseases linked to airborne pollution in the workplace. Contact eczema is the most common occupational skin ailment. Both respiratory complaints and skin complaints take a long time to develop, are often chronic, and they can appear after exposure has discontinued. Other respiratory diseases such as chronic bronchitis, allergic reactions like asthma, and diseases of the lungs are reported regularly. Reported cases of contact eczema and allergic eczema are also common. Permanent damage to the central nervous system caused by occupational exposure to organic solvents is still being reported at a rate of up to 100 cases per year.

In addition to respiratory and skin complaints, cancer and damage to the central nervous system, occupational exposure to chemicals can cause reproductive problems and acute toxicity in very rare cases.

Figures from the Product Register show that it has registered approximately 15 000 chemical products that are classified as hazardous to health and/or the environment, and another 10 000 products that may contain hazardous substances. There has been an increase in the number of sensitising and carcinogenic substances being registered, but this may be partly due to better registration and partly to the increase in the number of substances classified by the authorities, rather than to a real increase in the use of chemicals. Most of the chemicals in the register are substances with sensitising, corrosive or irritating properties or solvents that can damage the central nervous system. Cosmetic products, such as those used in the hairdressing industry, are exempt from this registration scheme.

Exposure to chemicals occurs in all the main occupational sectors in connection with the use of products such as cleaning agents, lubricants/cutting fluids, metal dust/vapour, mineral dust, fibres, organic/inorganic/biological dust, organic solvents, organic and inorganic gases, pesticides, plastic chemicals and monomeric/polymeric compounds and additives used in paint, varnish, glue, insulation and insulating foam. Some industries have greater problems than others, however, and workers in high-risk industries may be exposed to several chemicals simultaneously. A level of exposure considered safe when a single substance is involved is not necessarily safe in the context of simultaneous exposure to other substances. There is little knowledge currently available on the health impacts of this type of simultaneous exposure.

Figure 8.1 Occupational exposure to chemicals during hot work

Source Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion

Secondary exposure to chemicals can also occur in the workplace. For example, there are many substances which, when heated, break down and give off complex mixes of chemical vapours which may be highly reactive, irritating, sensitising or hazardous in other ways. This may take place in connection with heating or hot processes in such places as engineering works, foundries and smelting works.

Welding, thermal cutting, thermal coating, carbon-arc cutting, brazing, grinding and other types of hot work may produce toxic substances of possibly unknown structure that can irritate and have a sensitising effect on the respiratory system. This is one of the problems confronting the petroleum industry, which will have to dismantle a number of installations in the foreseeable future. This issue is being dealt with in cooperation between the Petroleum Safety Authority, the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority and the Norwegian Maritime Directorate, and was discussed in the white paper on health, safety and the environment in the petroleum industry (Report No. 12 (2005–2006) to the Storting).

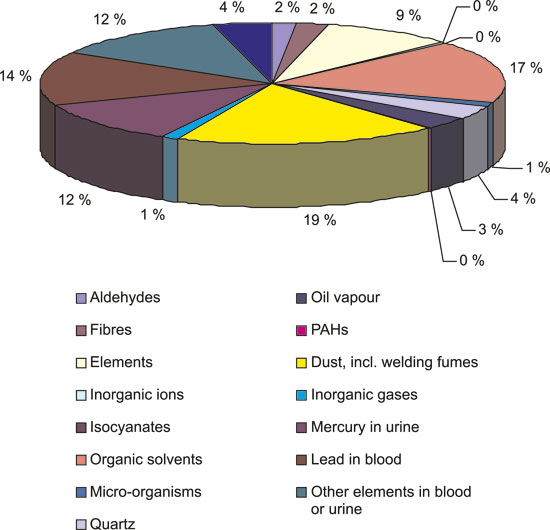

Figure 8.2 Exposure measurements in the EXPO database

Source Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion

The occupational exposure database (EXPO) maintained by the National Institute of Occupational Health registers data on some of the workplace exposure measurements taken in Norway, and can with certain reservations identify trends in occupational exposure to chemicals. This institute is Norway’s national research institute for occupational health and the working environment. Its activities include research, training and dissemination. The institute’s main objective is to compile and disseminate knowledge on the connections between work and health. One of the most important priorities for the institute is occupational chemical/biological exposure and its impact on health. Over 120 000 samples from approximately 5000 enterprises taken from 1984 to the present are stored in the EXPO database. Figure 8.2 shows a summary of the types of chemicals for which exposure measurements have been taken at Norwegian workplaces over the past 20 years.

Despite the quantities of data stored in the EXPO database, little of the information on levels of exposure to chemicals at Norwegian workplaces has been collated and our present knowledge is limited. Moreover, there are uncertainties regarding the data on which the assessment of chemical exposure and its impact on health are based.

Better knowledge, a stronger regulatory framework and better organisation of workplaces have made it possible to reduce worker exposure to harmful chemicals considerably. And not only have levels of exposure been reduced, the number of people exposed to chemicals has been reduced as the proportion of the workforce working under conditions that involve exposure has been reduced.

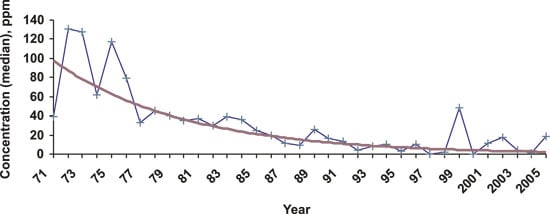

Figure 8.3 Trend in concentrations of styrene in the working atmosphere in Norway’s polyester industry from 1971 to 2006. The red line is a smoothed trend line.

Source Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion

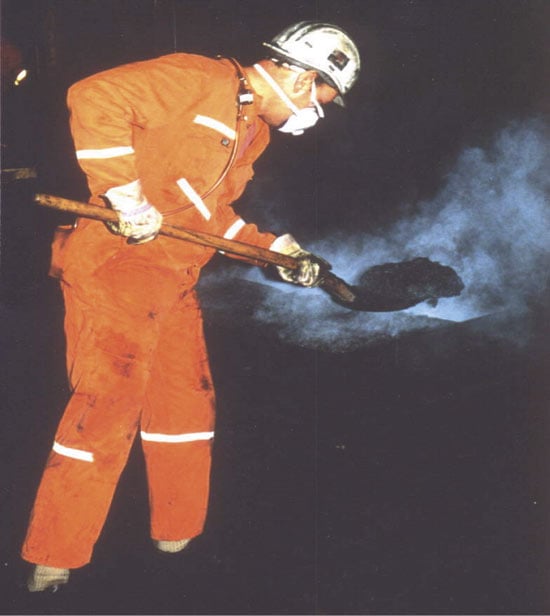

As an example of a declining trend in exposure, figure 8.3 shows that levels of exposure to styrene in the polyester industry have been reduced substantially from 1971 to the present. This has been brought about through a concerted effort by the industry itself and by the working environment authorities. Figure 8.4 shows a typical exposure situation in the smelting industry, which clearly shows why workers in this industry may be exposed to higher levels of PAHs than the general population, who are only exposed to lower levels released to the atmosphere.

A sound principle of preventive work is to focus on the measures that are likely to have the greatest preventive effects. And preventing injury to health from exposure to chemicals will have a considerable impact in the working environment, which is where most demonstrable injuries occur.

The development of a disease today is often caused by exposure that took place long ago. The onset of cancer, for example, may come as many as 30 years after the period in which exposure took place. This means that symptoms diagnosed today are not necessarily linked to current levels of exposure. It is just as likely that they are the outcome of previous levels of exposure. One example of a disease with a delayed onset is the type of lung cancer linked to exposure to asbestos, where new cases continued to appear long after asbestos was banned. In many cases it is difficult to establish clear connections between exposure to substances at a specific workplace and the impact of the exposure on health if there is a long delay between exposure and illness, particularly if a worker is no longer employed in the workplace where exposure occurred.

Figure 8.4 Exposure to PAHs in the smelting industry

Source Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion

8.1.1 Chemicals in the petroleum industry

A recent white paper on health, safety and the environment in the petroleum industry (Report No. 12 (2005–2006) to the Storting) gave an account of exposure to chemicals in the petroleum industry. During the drafting of this white paper, a joint working group was appointed to assess past and present exposure to chemicals in the petroleum industry. The group concluded that the working environment on the continental shelf is safe, though it identified a number of problems related to current work with chemicals. However, the group also noted that from the start of petroleum activities in 1966 until around 1980, too little was known about the risks associated with the use of and exposure to chemicals, and their impact on health. The group also concluded on the basis of current knowledge that it is reasonable to conclude that certain groups of employees may have been exposed to high concentrations of chemicals, and that this may have had long-term effects. An initiative has therefore been taken to survey historical exposure levels as far as possible.

According to Summary Report phase 6 (2005) on the Petroleum Safety Authority project Trends in Risk Levels – Norwegian Continental Shelf, many companies are not meeting their obligation to perform risk assessments of their use of chemicals, they use an unnecessarily wide range of chemicals that represent considerable health hazards, and they are doing little to phase out hazardous substances.

8.2 Protecting workers against hazardous substances

Chapter 3.1 presents a number of key principles of Norway’s chemicals policy, among others that prevention is better than remediation, that the business sector has a responsibility for the use of chemicals, that the substitution principle should be applied to phase out hazardous substances, and that consumers and employees are entitled to relevant information on chemicals.

These key principles are also reflected in Norway’s approach to protecting workers from hazardous chemicals.

Employers are responsible for safeguarding their employees from harmful exposure to chemicals and for ensuring compliance with the legislation. The Working Environment Act requires workplaces to be organised in such a way that employees are protected against accidents, injury to health or appreciable discomfort when handling chemical or biological materials. Employers are required to assess risk factors in the working environment and to take steps to reduce risk. Employees are required to take part in the organisation, implementation and promotion of systematic health, safety and environmental work. This includes using prescribed safety equipment, exercising caution and otherwise taking steps to prevent accidents and injury to health.

One well-established principle when it comes to the working environment is that worker protection should chiefly be based on the elimination of sources of exposure.

It follows from the requirements of the Working Environment Act relating to risk analysis and risk-reduction measures that employers must evaluate opportunities for substitution. This means that chemicals that may constitute a health hazard are not to be used if they can be replaced with non-hazardous or less hazardous chemicals, or with processes that are less hazardous for the employees. In addition, exposure times must be reduced to a minimum and the number of employees exposed must be kept to a minimum. Protective equipment should be used only if exposure cannot be prevented by other means.

Exposure to chemicals is regulated through indicative limit values for contamination of the working atmosphere. These norms are defined such that exposure for a full work week over a 40-year period will not cause any injury to health. Limits established to prevent injury to health from exposure to some constituents of air pollution are often based on lifetime exposure, i.e. 24 hours a day for 70 years. This reflects the fact that the general population also includes extremely sensitive individuals such as children, the elderly and the infirm, who also need to be protected.

Exposure near a source of pollution, as in the workplace, usually entails much higher levels of exposure than those encountered by the general population after pollutants have been dispersed and diluted in the external environment. On the other hand, the number of people who may be exposed to chemicals is higher in the general population than in the workforce, and it is not just human health that is at stake, but also the environment in general. In simple terms, in the external environment, many people and other forms of life are exposed to relatively low levels of pollution, whereas in the working environment, relatively few people are exposed to higher levels of pollution. These differences have engendered differences in chemicals policy and regulatory frameworks between these two sectors. For example, limit values applicable to the external environment are established by experts on a purely scientific basis, often based on extrapolations from animal studies or biological test systems. But such limit values are not widely used. As regards the working environment, however, experts provide a scientific basis for indicative limit values in relation to critical doses for humans, after which the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority determines these values in dialogue with the social partners. In practice, this means that limit values recommended for exposure to pollutants in air for the general population are lower than the indicative limit values that apply in the workplace. But one fundamental principle must hold: all use of chemicals in the workplace must be based on knowledge of their impacts on health and the environment, and on compliance with the legislation.

8.3 Finding a balance between working environment, health and environmental considerations

Measures to limit the use and impact of hazardous substances will have benefits in the form of lower exposure and emissions levels in a number of areas.

In general, important synergy effects can be achieved between measures implemented in the working environment and in the external environment provided that a balance is achieved between the two sectors in priorities and the input of resources.

In most aspects of chemicals management, any measures implemented may have a positive impact on the working environment, on health and on the external environment. For example, improving knowledge of the intrinsic hazardous properties of chemicals would be valuable in all three areas. As a case in point, substances with environmentally hazardous properties are not merely an environmental risk, they are also a risk to human health via the working environment or the external environment. This often applies to substances with reprotoxic and mutagenic properties. Since levels of exposure in the working environment are generally higher than they are in the external environment, the effects on health of occupational exposure to chemicals are easier to identify. Thus, there is considerable potential for transferring knowledge gained in a working environment context to the environmental sector. For example, PFOS, which has been shown to be persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic, was first found in the blood of workers at 3M in Canada, and 3M accordingly stopped using it in its products. Without this warning, levels of PFOS in the environment would probably have been much higher today than they actually are.

On the other hand, measures implemented in one of these fields may come into conflict with concerns in the other. There have been examples of targeted environmental measures that have actually increased the risk of harmful exposure of employees. In other cases, employee safeguards have led to higher releases of hazardous substances to the environment. An effective chemicals management regime requires good coordination and the incorporation of health and environmental data into risk assessments and measures. The Government will give priority to ensuring that impacts on the working environment, health and the external environment are all included in assessments of regulatory measures concerning chemicals.

Any prohibition or restriction applied to specific substances is likely to result in their replacement with other chemicals with similar performance characteristics, but with different impacts on health and the environment. In such cases, working environment and environmental considerations may conflict with each other, and additional measures may be necessary to resolve the situation. For example, persistent compounds might be replaced with more easily degradable compounds for environmental reasons without any consideration of the impact an alternative compound could have on the health of workers in close proximity to the source of pollution. Similarly, compounds that are an occupational risk may be replaced with compounds that are an environmental risk.

If regulation of a substance because of concerns in one area may reduce levels of protection in other areas, appropriate regulation in the other areas should be considered in advance in order to maintain a high level of protection in all three areas: public health, occupational health and the environment. In cases where it is impossible to reconcile these interests by means of normal measures and mechanisms, it will be necessary to assess the socio-economic benefits of the various measures and set priorities among them. In any case, the requirement of the Working Environment Act for a sound working environment and the prohibition against pollution in the Pollution Control Act provide guidelines for these assessments.

Companies involved in clean-up, take-back and collection of hazardous substances and products are a rapidly growing and necessary branch, like those involved in sorting of waste at source and waste treatment. However, all such activities entail occupational exposure of workers to the discarded substances from which the environment is to be protected. The Government will therefore provide a framework for such operations that safeguards worker health, public health and the environment. Workers involved in clean-up operations also risk exposure to hazardous substances for years after such substances have been banned. Risk assessments must therefore be carried out before new environmental clean-up operations are started, which include impacts on worker health and a review of possible measures for protecting worker health. A practical example of what can be done is technical modifications to vehicles used for kerbside collection of sorted waste in order to minimise the risk of harmful occupational exposure to bioaerosols.

Good documentation of possible health hazards to workers from alternative chemicals and new pollutants that may be generated after technological changes must be obtained, and must include assessments of critical doses for humans. It is important to take an overall approach to both prohibition and substitution, which means that health, safety and environmental considerations are weighed against each other and evaluated on the basis of impact assessments. This process must involve cooperation between industrial actors and supervisory authorities in relevant sectors. Cooperation and coordination mechanisms in chemicals policy are discussed further in Chapter 11.

Measures to ensure that information about chemicals is generally available will also help to improve chemicals management with respect to the working environment, to health and to the external environment. A greater awareness of routes of exposure and the effects of exposure would also be likely to improve understanding of the risk-reduction measures that are necessary in various areas. The Government has identified a need for cross-sectoral research in Chapter 6.

8.4 Measures and follow-up

The Government has made it clear that it expects enterprises to apply risk management tools to their use of chemicals. Moreover, the Government will:

give priority to inspection and control of what enterprises are doing to prevent injury to health from exposure to chemicals in the workplace, both in mainland industry and in the offshore oil industry

make provision for medical follow-up of groups concerned about the effects of past exposure to chemicals in the petroleum industry

give priority to improving knowledge on chemicals by maintaining the R&D effort in this field

give priority to the development and better utilisation of the existing body of data through monitoring and improved methods of collecting and collating data.

Between 2003 and 2006, the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority conducted a national campaign against hazardous exposure to chemicals. The goal of this campaign was to improve awareness of chemicals use in enterprises by encouraging them to survey the health hazards and assess the risks posed by the chemicals in their own working environments. This was intended to provide a basis for enterprises to draw up plans for reducing the risk of health injury. Employees also need better knowledge of the work operations they perform so that they can do more to ensure their own safety. The campaign focused on a few industries in which chemicals are widely used, encompassing over 10 000 enterprises and 110 000 employees:

Motor vehicle repair

Manufacture, maintenance and repair of machinery, metal goods, etc.

Reinforced thermoset plastics (boats, fibreglass tanks, etc.)

Publishing and printing.

An evaluation of the campaign was concluded in November 2006.

In the petroleum industry the focus is on integrating the chemical working environment into the overall risk management regime and achieving a better balance between the various health, safety and environmental considerations associated with the use of chemicals.

In 2006 and 2007, the Petroleum Safety Authority, in collaboration with the social partners, is conducting a project that will lay the groundwork for a historical risk assessment and for setting priorities for future chemical research efforts. This includes a survey of problem areas and gaps in knowledge. The Standing Committee on Labour and Social Affairs has pointed out the importance of ensuring that groups who are now concerned about the effects of past exposure to chemical health hazards in the petroleum industry are followed up by medical professionals (Recommendation S. No.197 (2005–2006)). The Government is encouraging follow-up in the form of examinations by occupational health specialists. The working environment authorities have taken the initiative to formulate joint guidelines for such patient examinations at all the occupational health departments at regional hospitals and to establish measures for coordinating this effort. Among other things, this will provide a better basis for evaluating any applications for occupational injury compensation that may be forthcoming.

The Government intends to maintain the research effort in the field of health, safety and environment in the petroleum industry, and has pointed to the need to learn more about exposure to chemicals. The industry will also be required to meet strict requirements relating to knowledge development, the development of risk indicators and monitoring and inspection of the chemical working environment.

The Government will take steps to raise awareness of chemical health hazards in the workplace. It has previously been noted, for example by the Office of the Auditor General (in Document No. 3:9 (2001–2002) and the Storting’s follow-up document) that the authorities do not have an adequate overview of the use of chemicals that represent health risks in the workplace, and that compliance with the provisions of the Working Environment Act relating to the replacement of chemicals that are hazardous to health is not satisfactory. Therefore, the Government has signalled its determination to strengthen the knowledge base by establishing the Department of National Surveillance of the Working Environment and Health at the National Institute of Occupational Health in 2006, and by establishing a department for documentation and analysis at the central office of the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority in Trondheim.

To improve documentation on the sales and use of dangerous chemicals, the Government will consider the possibility of expanding the duty to declare chemicals to the Product Register to include some chemical substances and products that are not regulated by the provisions of the Chemical Labelling Regulations. Examples of such substances are cosmetics and solvents. For further discussion of this proposal, see Chapter 9.9.

Data from exposure measurements for chemical/biological/physical factors registered by the enterprises that monitor and record such information is the property of the individual enterprise. This data is used to some extent in documenting the enterprises’ own risk assessments, but is not generally accessible at present for the purpose of compiling information on exposure levels and trends at a level higher than the individual enterprise. As a result, the information available to authorities and decision-makers on national exposure trends in Norwegian workplaces is very limited. Moreover, a large number of new chemicals and altered industrial processes are introduced every year. In consequence, the pollution situation is continually changing, and «new» problems associated with chemical, biological and physical exposure factors are emerging all the time. This creates a pressing need to collect and organise information in this field. To ensure better data capture, exposure data from enterprises should be available in a suitable format. A move is being considered to develop a system based on existing law which would provide for the systematic transfer of exposure data from the enterprises to the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority and the Petroleum Safety Authority, and on to the National Institute of Occupational Health for entry into the EXPO database. There is also a need for systematic exposure surveys in selected, relevant industries for the purpose of obtaining representative measurement data on selected pollutants in Norwegian workplaces. Registering data of this type in the EXPO database would provide a basis for studying trends in exposure levels over time, improve the knowledge base and form part of the basis for the work of the Department of National Surveillance of the Working Environment and Health.