6 Greater efforts to build up knowledge about chemicals

Although we are aware of the impacts some chemicals may have on health and the environment, our knowledge of most substances is very limited. In order to choose alternatives that have the least negative impact on health and the environment, we all need information on which substances and options are least harmful to our health and environmentally favourable. The Government intends to develop a knowledge-based management regime for chemicals, and will therefore support a substantial increase in research on and monitoring of ecological toxins and other hazardous substances. The Government wishes Norway to play a leading role in efforts to prevent the dispersal of hazardous substances and damage caused by such substances. An essential basis for this is research and monitoring results that can be used as a basis for developing regulatory measures at national and international level. In the Government’s view it is also necessary to take a coherent and clearly targeted approach to improving the dissemination of information on sources of pollution and the risks to and impacts on health and the environment.

The Government will

strengthen research on hazardous substances and promote cross-sectoral research more actively

develop an integrated survey and monitoring programme for ecological toxins by 2009

work towards use of the REACH legislation to obtain basic information on as many substances as possible

build up knowledge of ecological toxins in the Arctic

survey the use of nanomaterials and evaluate how existing legislation chemicals and their use and release can be used to ensure protection of health and the environment in connection with the use and release of nanomaterials

build up a Norwegian environmental specimen bank of ecological toxins for research and monitoring purposes.

6.1 What challenges are we facing?

Before we can deal with risks, we must know what they are. We must also be able to document both levels and trends for dangerous substances in the environment before we can determine what action needs to be taken. However, we have limited information on the hazardous properties and effects of most substances, and not only for little-used substances. We lack adequate information on 65 % of all substances that are produced in or imported to Norway in amounts of more than one tonne every year, and have no information on 21 % of them. The new REACH legislation will play an important role in remedying this situation.

Textbox 6.1 Combined impacts of ecological toxins

Very little is known about the combined impacts of different ecological toxins, which may either reinforce or weaken each other’s effects. International research on this issue has been intensified, but is very difficult because of the large number of chemicals and the complicated principles involved. Heavy metals can for example reinforce the impacts of exposure to other chemicals. One study*, which was presented at the DIOXIN2006 symposium in Oslo, has shown that co-exposure to PCBs or PDBE and methylmercury can enhance developmental neurotoxic effects. This may explain why neuropsychological defects in children are found to vary in severity from one area to another.

* Fischer C, Fredriksson A, Eriksson P; Proc. DIOXIN2006, Oslo, Norway

In order to gain support for international regulation of chemicals, we must be able to document the probability that they pose risks to health and the environment. The international conventions that restrict the use of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and heavy metals require documentation before regulation of new substances can be considered. Even if the precautionary principle is used actively, a lack of information about the properties of substances, where they are present, transport routes and effects will limit progress and make it more difficult to regulate chemicals at both national and international level. There is insufficient documentation for many substances today, even substances that we suspect of having very serious effects and would like to see regulated at global level. There are also gaps in our knowledge of hazardous substances in products and of less dangerous alternatives.

The lack of basic information on large numbers of substances is cause for concern. These substances are found in a wide range of ordinary consumer products and enter the environment by different routes. We need to obtain information on their spread in the environment, where they are present and what effects they have on natural ecosystems and human and animal health. It is also important to identify mechanisms of action for the most commonly found substances, and how serious their health impacts are. To build up this knowledge will require more industry involvement in testing and risk assessments. This means that industry will have to allocate more resources to these processes.

Textbox 6.2 Hazardous substances in the blood of pregnant women

Analyses have shown that blood plasma from pregnant women contains a number of hazardous substances that are used in ordinary consumer products, such as brominated flame retardants and perfluoroalkyl substances. The levels found were not particularly high, and the results do not indicate that the women or the fetuses were exposed to an acute health risk. The effects of these substances on health have not been completely clarified, but the mere fact that they are present and accumulating in people gives grounds for concern.

It is particularly important to learn more about the effects of long-term exposure and about total exposure of people and animals to ecological toxins. There is special concern about possible health effects in future generations, since various substances are transferred to the fetus through the umbilical cord and to infants through breast milk.

Internationally, there is a lack of quantitative measurements of ecological toxins in the environment, animals and people. This applies both to known ecological toxins and to substances that have more recently been recognised as sharing similar properties. Contributions from Norway are therefore important. For example, monitoring of recently recognised ecological toxins in the Arctic by the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority and the Norwegian Polar Institute has been instrumental in raising awareness at international level of the properties of these substances and their long-range transport potential.

The Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), which has a Norwegian secretariat, is playing an important role in assessing the extent of pollution by POPs and heavy metals in the Arctic. Considerable weight has been given to AMAP’s results in the EU’s work on persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic substances (PBT) and in similar work within the framework of the OSPAR Convention. The white paper on Norway’s integrated management plan for the Barents Sea–Lofoten area (Report No. 8 (2005–2006) to the Storting) proposed an integrated system for monitoring the state of the marine environment, which is to include monitoring of POPs and other ecological toxins. This will provide important information on the spread of these substances.

There is a pressing need to carry out environmental screening of a larger number of chemicals in order to build up information on little-known substances. This means systematic collection of samples to obtain basic information on the presence and concentrations of «new» substances that are not included in the ordinary monitoring programmes. There is often little or no international data on these substances, so that data from Norway is very important internationally, as has been shown by the screening done through AMAP.

6.2 Initiatives to build up knowledge

REACH will involve a concerted effort by industry to build up knowledge

Extensive testing of chemicals is needed to reveal whether they have properties that make them hazardous to health or the environment. Until now, the legislation has not required much industry testing of chemicals that are already in use. The new REACH legislation will make very important changes to this situation, and industry will have to provide large amounts of basic information on chemicals to meet the new requirements. See Chapter 5 for further details on the REACH legislation. It is important that methods of testing and evaluating chemicals without animal testing are developed and taken into use.

Figure 6.1 The research vessel Lance in the Wahlenbergfjorden, Svalbard

Source Norwegian Polar Institute

Focus on research

The Government will strengthen research on hazardous substances, both by expanding research activities in this field and by building up the research institutions and public bodies that are involved in evaluating documentation and information on hazardous substances.

To ensure that progress nationally and internationally in evaluating measures relating to hazardous substances is as rapid as possible, the Government will establish a research initiative that will give priority to building up knowledge about:

metabolisation of hazardous substances in organisms and effects on animals and humans

sources, presence, releases and effects of ecological toxins throughout the food production chain from farm to fork

the damage caused by hazardous substances, including cancer, birth defects and reproductive problems, genetic damage, and damage to the immune and nervous systems

health and environmental effects of long-term low-dose exposure and the effects of combined exposure to several substances

bioavailability of particulate-bound ecological toxins and their transport in the food chain

inputs, deposition and effects of long-range pollutants and possible synergies between chemical pollution and climate change, especially in the Arctic

substances recently recognised as ecological toxins, for example halogenated compounds

environmental problems related to medicines, metabolites of medicines and cosmetic products

health and environmental issues associated with nanotechnology and impacts of expanding its use

risk to people of acute poisoning on exposure to hazardous substances.

In addition, the initiative will be designed to develop and improve analytical methods for new hazardous substances, and to improve knowledge of the content of hazardous substances in finished goods and alternatives to the use of such substances in products.

Textbox 6.3 The Zeppelin station at Ny-Ålesund in Svalbard

The station is located at an altitude of 474 metres on the Zeppelin mountain, overlooking the settlement of Ny-Ålesund in Svalbard. Measurements at the station began in September 1989. The station is part of Norway’s monitoring network for long-range air pollutants, and the results are also reported to international networks. The station is important because it is located far away from sources of pollution, and the results document inputs of pollutants to the Arctic and where they originate. The monitoring programme includes measurements of 11 metals and six groups of persistent organic compounds in air.

Figure 6.2 The Zeppelin station

Source Norwegian Institute for Air Research

There is a pressing need for cross-sectoral research on chemicals, and the Government intends to encourage cooperation in this field. For example, we need to know more about the health outcomes of exposure to chemicals, and epidemiological surveys are needed that link information on exposure and on health effects. For example, data from working environment studies, where levels of exposure to hazardous chemicals are often higher than elsewhere, can provide useful and much-needed information on critical exposure levels and health outcomes in people. In addition, more data is needed on other forms of human exposure to chemicals via the environment. Cooperation between different disciplines and between experts in different sectors will be very valuable in further research on chemicals.

The Arctic as a barometer of global chemical pollution

Better information on ecological toxins in the Arctic will be of strategic importance in international efforts to reduce emissions of these substances. The Government will therefore give priority to building up knowledge of the presence and dispersal of such substances in the Arctic, the importance of climatic conditions for their transport, and the accumulation and degradation of ecological toxins in the Arctic. The development of models to describe the transport, uptake and metabolism of these substances in food chains will be an important element of this work.

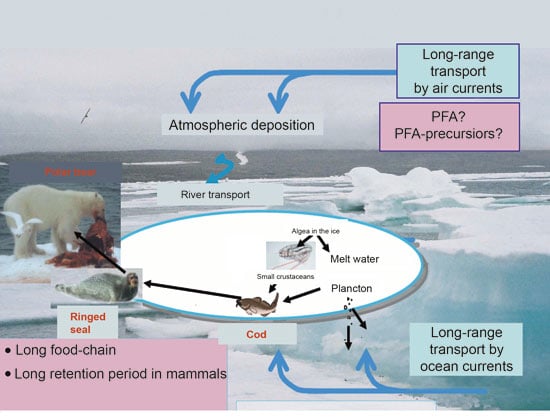

Figure 6.3 Transport of perfluoroalkyl acids and their accumulation in Arctic food chains

Source Derek Muir, National Water Research Institute, Canada

Climate change is expected to result in major changes in transport and dispersal patterns and in patterns of exposure to ecological toxins. Projected changes include higher precipitation, stronger winds, more leaching and runoff, and higher temperatures, and the overall results will be greater exposure of people and the environment to ecological toxins and different patterns of exposure.

Data from the Arctic are very useful because there is broad international agreement that substances that are found in this region, far away from sources of pollution, constitute a serious problem. Because local emissions are low, the Arctic is a suitable area for registering long-range transport of ecological toxins and following trends over time. A combination of several physical, chemical and biological factors and a cold climate results in high levels of ecological toxins in species at the top of food chains both in mainland Norway and in the Arctic. For example, results obtained from monitoring of brominated flame retardants in the Norwegian Arctic have been used in international efforts to restrict the use of these substances.

Figure 6.3 illustrates the fact that pollutants may follow a variety of routes, and shows that more knowledge is needed. Perfluoroalkyl acids such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) may be released to the environment when they are produced or from products that contain these substances. Their presence in the environment may be a result of long-range transport of perfluoroalkyl acids themselves or of substances that break down into perfluoroalkyl acids. We have not yet identified the main sources of perfluoroalkyl acids in the environment.

Nanomaterials

Nanomaterials contain particles of extremely small dimensions (less than 100 nanometres). Large investments are being made in the development and use of materials and products based on nanotechnologies. On the basis of current knowledge, there is no reason to believe that nanoparticles pose special health or environmental problems. However, there is great uncertainty associated with nanotechnologies. For example, little is known about possible effects on the health of workers in nanotechnology-based industries.

The development of nanotechnologies is expected to result in rising exposure of people and the environment to nanoparticles. The properties of chemical substances in the nanophase may be different from those they show in bulk. There is therefore a rapidly growing need for knowledge of the potential health and environmental effects of such materials; for instance, we need to know whether they may be persistent or bioaccumulative, and how they may interact with biological systems. It is important to meet this need adequately at an early stage of the development and implementation of nanotechnologies. The Government will therefore step up research on health and environmental effects of nanomaterials.

The Government will survey the extent to which nanomaterials are being used and evaluate how the legislation governing the use and releases of chemicals can be used to ensure protection of health and the environment during the use and release of nanomaterials.

Environmental monitoring

The focus of the environmental monitoring programme is on the occurrence of known and recently recognised ecological toxins and related problems, environmental trends, and identifying the need for control measures and other action. The Government intends to obtain more knowledge of the occurrence of persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic substances in the environment, and will by 2009 develop an expanded, integrated monitoring programme, including screening, for such substances.

The Government wishes Norway to play a leading role in following up international commitments and recommendations in this field. The Government will take steps to ensure that there is adequate documentation of the situation in Norwegian territory, including documentation of ecological toxin pollution in Arctic areas. This process will also make use of existing infrastructure. The integrated monitoring system for the marine environment proposed in the white paper on Norway’s integrated management plan for the Barents Sea–Lofoten area (Report No. 8 (2005–2006) to the Storting) will be important in this connection. Under the EU Water Framework Directive, a list of 33 priority hazardous substances has been established, and steps are to be taken to reduce releases of these substances. The Government will therefore enhance the monitoring of several of these substances, particularly in connection with implementation of the directive.

In Norway, the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority has the main responsibility for overall information on hazardous substances generally and on inputs, dispersal and levels in the environment, and for deciding which parameters and methods are to be used in monitoring programmes. Other agencies and users also have a responsibility for obtaining information on how their own use of chemicals influences health and the environment.

It is important to ensure good coordination of monitoring programmes and communication of the results. Steps to ensure this will be considered in drawing up the integrated monitoring programme for ecological toxins.

Monitoring of pesticide residues in the environment has shown that many of the substances in the programme are present in streams and rivers. There is only limited information on pesticide residues in ground water in Norway. However, such residues are a problem in many countries in Europe. A survey of pesticide residues in Norway’s most important aquifers should therefore be conducted. Furthermore, testing for pesticide residues should be expanded to include all substances that may be environmentally harmful, including pesticides used at low dosage rates and degradation products. A greater emphasis on monitoring of pesticide residues will also be important in Norway’s implementation of the Water Framework Directive.

The Norwegian Agricultural Environmental Programme, JOVA, monitors the transport of particles and nutrients, and also pesticides, in agriculturally dominated catchments in Norway, and provides data that can be used in modelling. Expansion of the programme to include measurement sites on different types of land where pollution of soils and ground water would have serious consequences for people and the environment should be considered. This would make it possible to use the measurement sites as part of a network for terrestrial monitoring of ecological toxins that can be traced back to Norwegian sources such as agriculture. To obtain background levels of hazardous substances, results from the measuring stations used in the terrestrial environmental monitoring programme TOV and the programme for monitoring of small catchment areas should also be taken into account.

Expansion of environmental screening programmes

Short-term, intensive screening programmes and analyses are also needed to detect ecological toxins that are not included in the environmental monitoring system described above. The Government will intensify screening of ecological toxins. The numbers of substances, media (sediment, water, living organisms) and localities sampled will all be increased. Both environmental samples and human samples (blood, breast milk) will be included. This will make it possible to gain a much better picture of human and environmental pollution levels. Background stations in the Arctic are important in this context.

National surveillance of the working environment and health

There is currently no adequate overview of data and documentation on the working environment and occupational illness and injury. The Government is seeking to remedy this, and therefore established the Department of National Surveillance of the Working Environment and Health at the National Institute of Occupational Health in 2006. The department’s tasks include collecting, processing and disseminating relevant information on occupational exposure to chemicals, time trends and health effects.

Textbox 6.4 The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study

This study is being run by the health authorities, and involves the collection of biomaterial (blood and urine) from mothers, fathers and children in a biobank. The target sample size is 100 000 births, and sampling is continuing for eight years up to 2007. This and other research biobanks can be expanded to include other biomaterial (for example breast milk), and can provide an important basis for an environmental specimen bank. A certain quantity of biomaterial is needed to gain the full benefit of analyses of large numbers of environmental samples in connection with monitoring population exposure.

Establishment of a good environmental specimen bank

An environmental specimen bank is a collection of samples that are systematically collected over several years at the same sites at the same time of year and stored frozen. When samples have been systematically collected from different sites in this way, it is possible, for example in the event of problems involving new substances, to retrieve samples from the specimen bank and quickly establish time trends and thus follow developments over time. The Norwegian Pollution Control Authority has started a pilot project in which biological samples from mussels and fish are being stored in an environmental specimen bank.

The Government will consider expanding and further developing this specimen bank so that it can provide a satisfactory solution for research and monitoring of ecological toxins. If the specimen bank is to be a good tool for satisfying future knowledge needs, it will have to be expanded and developed a good deal, so that it also includes sediment samples, precipitation, birds’ eggs and human tissue from a variety of sites. Collection of more samples from the Arctic will be given priority.

The development of an environmental specimen bank will be considered, taking into account the proposal for a marine environmental specimen bank in the white paper on Norway’s integrated management plan for the Barents Sea–Lofoten area, the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study, and the marine biobank Marbank that has already been established in Tromsø.