4 Monitoring and knowledge development

“We therefore need to ask people not only about general satisfaction, but also about joy and mastery in everyday life, about a sense of meaning, freedom of action, respect and belonging, about hopelessness, stress or pressure. We need to combine such data with information about actual living conditions, social conditions and living and working conditions – putting people in a wider context. And finally, we need to monitor the development over time so we can understand who gets worse and who gets better – how, in what way and under what circumstances”(9).

The Government’s goal is to ensure adequate knowledge about wellbeing in the population, how wellbeing is distributed across different groups, and how wellbeing develops over time.

To achieve this goal, regular national, regional and local wellbeing surveys will be conducted that encompass different geographical levels with good representation from different population groups. This is particularly important, as there is an increasing proportion of people who, for various reasons, have immigrated to Norway, in addition to an increasing number of descendants of individuals with immigrant backgrounds, including those with one Norwegian-born and one foreign-born parent. The data will be used to monitor developments over time and conduct sector-relevant analyses. Furthermore, the National Indicator Framework (1), which is currently under development, will be regularly updated and further developed as needed.

Comprehensive and regular wellbeing surveys could provide answers to how different aspects of wellbeing develop and are distributed across society. Wellbeing surveys could therefore be an important management tool for prioritising efforts and evaluating change over time, for example as a result of pandemics, changes in population composition or specific implemented measures. The National Wellbeing Survey conducted by Statistics Norway in March 2021 during the pandemic shows that satisfaction in the population was significantly lower in March 2021 than in March 2020. The same applies to optimism about the future and a meaningful everyday life. The survey shows a decline in 10 out of 12 indicators of subjective wellbeing between 2020 and 2021. This decline coincides with changes in living conditions, including an increase in the proportion of people who report having health or mental health problems, sleep issues, pain, lack of social contact and loneliness. Overall, the number of restrictive measures implemented during a pandemic appears to have had a direct effect on the wellbeing of the population. This effect seems to vary according to the intensity or duration of the measures, and it is assumed that wellbeing will return to a more “normal” level when the pressure decreases (11).

Average satisfaction in the population has improved since the “low point” in 2021, but it is still somewhat lower in 2024 than it was in March 2020. It is also lower than in surveys conducted prior to the pandemic (for example, Folkehelseundersøkelsene [County Health Surveys] (available in Norwegian only) (26) and the Gallup World Poll4. The sense of meaning, engagement and emotions have scarcely changed since 2021, while satisfaction with physical health has continued to decline. Satisfaction with mental health has not improved either. Recent data from the County Health Surveys show that the level of most wellbeing indicators is lower than both before and during the pandemic (26). This applies across age, gender and education.

The factors included in both the national and local measurements of wellbeing in the population, along with the indicator framework, will form a knowledge base for the work to develop wellbeing as a measure of and for societal development in Norway. Access to qualitative knowledge through participation processes could also provide greater insight into the wellbeing of different groups.

In addition, the international measurements published in the “World Happiness Report” and the “Human Development Index” can be an indicator of developments in Norway compared with other countries.

4.1 National measurements: Wellbeing in Norway

There are two main sources of knowledge about the population’s wellbeing. One is register data, i.e. information about wellbeing that can be retrieved from public registers, which encompasses the entire population. These registers only cover objective aspects of wellbeing, such as income and wealth, crime, employment, education, mortality/life expectancy and certain aspects of living conditions. However, register data does not cover all relevant aspects of the objective wellbeing.

In order to also include the subjective aspects of wellbeing, it is necessary to conduct sample surveys and ask people how they are doing.

For years, Statistics Norway has been conducting surveys on the living conditions of the population, starting in 1973. In recent years, the Living Conditions Survey has been coordinated with the surveys that Norway is obliged to conduct as part of the EEA agreement, EU-SILC (European Union Survey of Income and Living Conditions). These surveys are conducted annually and consist of three parts: One part is a core set of questions determined by Eurostat (the statistical office of the EU), another part is also determined by Eurostat but consists of topics that vary from year to year, while a third is nationally determined. Other sample surveys that provide information on aspects of the population’s wellbeing include the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS), the European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS), the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) and the European Time Use Surveys (HETUS).

Together with register data, these sample surveys provide a large amount of important information about the population’s wellbeing, although they do also have certain weaknesses: Subjective wellbeing is relatively poorly covered and the surveys are conducted in the form of telephone interviews, which may lead to an underreporting of negative feelings and evaluations. Another weakness is that the ability to see cross-connections is limited by the rotation of themes.

These weaknesses were why a new measurement system that included recommended questions and methods for conducting wellbeing surveys in Norway was presented in 2018 in the report Livskvalitet – Anbefalinger for et bedremålesystem [Wellbeing – Recommendations for a better measurement system] (available in Norwegian only) (9). This report provides both recommendations on measurement tools for comprehensive wellbeing measurements (a dedicated wellbeing survey) and a minimum battery of questions to be used in surveys that do not focus solely on wellbeing, or that are smaller in scope but also seek to cover key components of wellbeing. These surveys are conducted online, which means that participants do not have to engage with an interviewer. Surveys like these also allow for a larger sample size than what is common for living condition surveys.

The recommended measurement system for a comprehensive measurement of wellbeing forms the basis for the national population surveys on wellbeing conducted by Statistics Norway. From 2022, wellbeing was established as a separate official statistic at SSB.no, and key parts of the survey are published as tables in Statistics Norway’s statistics bank, StatBank, as part of its statistics programme for the 2024–2027 period. Statistics Norway has decided to limit the statistics to subjective wellbeing dimensions, and the following indicators are included in the statistics: Satisfaction with different areas of life; (life in general, physical and mental health, the place one lives, available leisure time, financial situation); Overall satisfaction with life; Meaning and mastery (optimism for the future, sense of meaning, sense of engagement, sense of mastery and fulfilment, rewarding social relationships), and Positive and negative emotions. The indicators are broken down into various personal characteristics such as gender, age, level of education, income, economic status, civil status, national background, etc. Consideration should be given to whether the question “What does a good life mean for you?” from the survey conducted by Norstat in spring 2023 (see Chapter 4.3) should be included in the national measurements.

The system still has some weaknesses. The wellbeing surveys have a higher non-response rate than the surveys conducted in the form of telephone interviews. The non-response rate is particularly high among those with a lower level of education and among those over the age of 80. It is also significantly higher among people with immigrant backgrounds. These are groups that also have relatively high non-response rates in other surveys, although the web-based survey method seems to reinforce these issues.

The wellbeing survey does not include children and young people under the age of 18, nor does it provide information on minorities such as the Sámi people and national minorities5. Nor does the current system provide figures at a lower geographical level than the county.

Overall, these weaknesses indicate a need to establish a system that ensures representativeness of the above-mentioned the groups and that enables annual data collection in addition to existing data sources.

4.2 Local measurements: Fylkeshelseundersøkelsene [County Health Surveys]

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health has since 2019 measured wellbeing at the local level through Fylkeshelseundersøkelsene [County Health Surveys] (available in Norwegian only). The aim of these surveys is to provide an overview of public health issues at regional and local levels and to contribute to knowledge for use in cross-sectoral municipal and county authority public health work. Among other things, the surveys have contributed to mapping mental health challenges and problems of loneliness across the country. These have shown municipal variations that are not reflected in national statistics.

The data collected helps county authorities, municipalities, health authorities and other organisations to develop and implement targeted public health measures and policies. The surveys are primarily conducted online. Large samples have provided data at the municipal level, and in some cases, also from smaller geographical units, such as city districts. They also provide data on minorities such as the Sámi people.

The purpose of the County Health Surveys is to fulfil the counties’ obligations under Section 21 of the Norwegian Public Health Act, “Overview of public health and health determinants in the county. County authorities shall have a sufficient overview of the population’s health in the county and the positive and negative factors that may influence this.” Wellbeing questions were included in the survey in 2019. The County Health Surveys is one of several sources for the work on preparing four-year documents and maintaining an ongoing overview in accordance with specific requirements in the regulations relating to public health.

As the County Health Surveys have several purposes, it is the so-called “minimum battery” from the above-mentioned measurement tool that was included with certain additional questions regarding such as happiness, gratitude and wellbeing in the local community. The minimum battery is a fixed element in the County Health Surveys to ensure comparable data across different surveys and regions over time and against similar questions in Statistics Norway’s national surveys. This battery encompasses the key domains of wellbeing, including both subjective and objective components.

The County Health Surveys have some of the same weaknesses as Statistics Norway’s Wellbeing Surveys. Young people under the age of 18 are not included, and there is a relatively low response rate among the youngest and oldest age groups and various immigrant groups.

Strengths of County Health Surveys include the opportunity to obtain statistics at the municipal and district level, as well as the fact that the surveys are adapted for register links and the opportunity to build panel data (follow up people over time). Statistics at the municipal level are important because municipalities are responsible for areas such as schools, health, the local community, etc. that are of significance for the wellbeing of the population in each municipality.

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health offers to carry out County Health Surveys on behalf of the county authorities, cf. Section 21 of the Public Health Act and Section 7 of the Regulations relating to the overview of public health. Fylkeshelseundersøkelser [County Health Surveys]. By the end of 2024, the County Health Surveys will encompass all counties apart from Trøndelag County Authority, which has other data sources. Data has been collected from around 450,000 people in the past four years. For some county authorities, there are now several completed surveys that offer comparisons over time at the regional and local level, and there is follow-up data from the same individuals for a significant sample in certain counties (FHUS koronaundersøkelsen [County Health Surveys, COVID-19 survey] (available in Norwegian only)). In order for a measurement system to collect data at the local level and monitor developments over time, it is essential to have a system for collecting data at both the county and municipal levels.

4.3 Measurements of wellbeing among children and young people

National and local surveys do not include children and young people under the age of 18. The most important source of knowledge about wellbeing among children and young people is Ungdata (27). Ungdata poses several questions about wellbeing and provides figures for all municipalities and counties throughout Norway, and it has been used for monitoring for the last decade. Wellbeing was included as a separate theme in Ungdata in 2020. Since 2010, 915,000 young people from nearly all Norwegian municipalities have participated in the youth section of the Ungdata surveys. Since 2017, more than 150,000 children in year levels 5–7) have responded to the Ungdata Junior survey. Ungdata can therefore provide good insight into what it is like to be young in Norway today. The Norwegian Institute for Welfare Research (NOVA) at OsloMet – Metropolitan University is responsible for conducting the Ungdata surveys in collaboration with the country’s seven regional centres of expertise in the field of substance abuse (KORUS). This collaboration is linked to the implementation of the local Ungdata surveys and the development of Ungdata as a tool for municipalities and county authorities. Ungdata is a useful source of knowledge for the overview efforts of county authorities and municipalities under the Public Health Act.

Ungdata Plus is a new survey, where 12,000 children aged 10–13 in Vestfold and Telemark were invited to take part in the survey in the spring of 2023. Participants will be followed up through repeated surveys into adulthood. The aim of Ungdata Plus is to learn more about the links between leisure habits, wellbeing and health. Unlike the ordinary Ungdata survey, which provides an overview of situations in the various municipalities and among different groups of children and young people at one point in time, Ungdata Plus will follow the same respondents over time.

Figure 4. Word cloud with words most often mentioned by people when asked what a good life is for them

Prepared by Henrik Lindhjem, Menon Economics

Ungdata Plus is a collaboration between KORUS South, Vestfold and Telemark county authorities, the University of South-Eastern Norway and NOVA – OsloMet6.

Children and young people are a focus area of Statistics Norway’s statistical programme for the 2024–2027 period. In 2024, Statistics Norway will ask questions about wellbeing in its survey on children’s leisure time, in which children as young as six years old will participate. This survey will be conducted every three years.

Several of the indicators on children and young people in Statistics Norway’s proposal for an indicator framework (1) are obtained from Ungdata. In future work, it must be assessed whether these are sufficiently comprehensive for children and young people’s wellbeing. Statistics Norway is considering whether there may be a need to prepare a separate set of indicators for children and young people, where Ungdata would be an important source. In addition, the annual pupil survey would

be a good source of data. Statistics Norway notes that the OECD has selected a solution with a separate set of indicators for children and young people. Children’s right to participation must be safeguarded in future work.

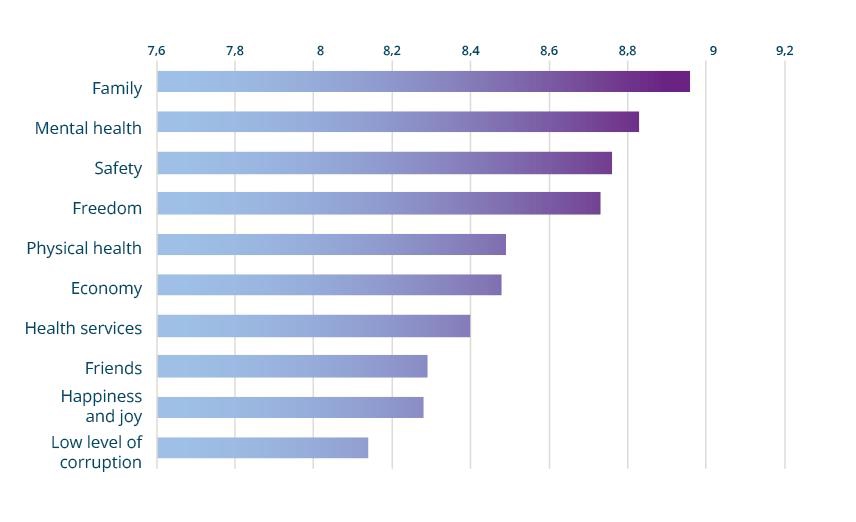

Figure 5. Highest ranked areas for people’s lives (score above 8)

4.4 The population’s perception of what is important for a good life

As part of the work on the National Wellbeing Strategy, a survey was conducted among the Norwegian population to investigate what the people themselves perceive as important for a good life. This survey was conducted with Norstat’s respondent panel in March 2023. It was representative of the Norwegian population based on known socio-demographic characteristics such as age and education and had a response rate of 22.5 per cent. Although the response rate is low, the responses are in line with what was identified by other research, both in Norway and internationally (28, 29).

The survey began with an open question formulated as follows: “What is a good life for you?” People were asked to provide up to five key words or brief sentences. The results are displayed as a word cloud in figure 4, where the size of the words describes their frequency. As the figure shows, family and health are the dominant themes. These are followed by finances, friends, freedom, security, love, work, (good) food and (good) relationships. While the adjective “good” was typically used in conjunction with health, adjectives mentioned in connection with “finances” or “money” were typically related to security, stability, independence (and rarely linked to wealth). Relationships and friends were often described in connection with the adjectives “good” and “close”. The word cloud illustrates the rather broad diversity in what people describe as good lives.

The survey also had a set of 42 aspects/areas of life, where respondents were asked to indicate how important each of the areas were for a good life on a scale from 0 (not important at all) to 10 (very important). The ten most important areas are shown in figure 7.

The rating largely coincides with the open-ended question in the first part of the survey, with family emerging as the highest ranked area of people’s lives. In Statistics Norway’s proposed framework, there is currently no specific indicator for family relationships. In the future, the inclusion of family relationships in the indicator framework should be assessed.

There is a strong consensus when the results are broken down by age, gender and party affiliation (“Which party would you vote for if there was a general election tomorrow?”). This means that these aspects of life are important, regardless of political views, age or gender. However, there are some differences between the groups. For example, those with low incomes (<NOK 200,000 personal income) will rank certain areas somewhat differently than those with high incomes (>NOK 800,000). However, these are minor differences, and 9 out of 10 areas are ranked among the top 10 by both low and high income earners. The data material is too small with too limited information to enable analyses at the group level. In order to investigate, with greater certainty, perceptions of what is important for a good life among the different groups, larger and more detailed surveys must be conducted. This particularly applies to the various minority groups. Although data from international surveys show a high degree of consistency between different countries and cultures, some of the areas emphasised for a good life will be influenced by local conditions, history and culture.

4.5 Research and knowledge development

Norway has consistently scored high on the international measurement of wellbeing as indicated in the World Happiness Report (30). This report ranks the subjective wellbeing for most countries in the world and has been published by the UN Sustainable Development Network annually since 2012. It is worth noting that the ranking of a nation’s wellbeing depends to a large extent on how wellbeing is defined7. However, the results for 2023 showed that Norway was the only Nordic country to drop in this international ranking, from first place in 2017 to eighth place in 2022 and to seventh place in 2023, 2024 and 2025 (31). More knowledge is needed about the reasons for the decline in wellbeing in Norway. This development may reflect a number of interconnecting factors. The Norwegian Monitor survey (32) indicates that less satisfaction may be linked to less optimism about the future in the form of greater concerns about the economy, working life and sustainability, particularly among those under the age of 40.

We know a great deal about what can affect an individual’s wellbeing. Crucial factors include genetics and personality traits, individual social and financial conditions, and health-related issues such as illness and chronic pain. Other factors include social changes and societal structures, developments on international stock exchanges, climate change and war. New research from Norway emphasises the importance of environmental factors, such as perceived discrimination and social support (33), in addition to factors such as crime and security. Other environmental factors such as access to nature and cultural environments, food safety, physical activity, a sense of belonging and social cohesion also show a positive correlation with wellbeing, while pollution and insecurity in neighbourhoods are negatively associated. Social and economic inequality in society generally has a negative impact on the wellbeing and may have negative ripple effects, such as greater mistrust. There are also indications that improving the wellbeing can have a protective effect against various physical and mental health issues.

Yet there are significant knowledge gaps. We know too little about what would be the best instruments to promote and equalise wellbeing in the population, and about how the importance of the aforementioned influencing factors, and the interactions between them, varies across individuals and population groups, as well as over time. Changes, initiatives and reforms can influence one another so that their effects become complementary or counteractive. Knowledge of such complex processes requires regular surveys and up-to-date research. We also have insufficient knowledge about effect size, causal relationships and effective measures. In general, it appears that each individual impact factor has relatively little significance on its own (34) but that they are amplified in interactions with other risk or health-promoting factors, which together constitute chronic burdens or enduring resources. In other words, there is extensive knowledge about associations and individual contexts, but limited knowledge about complex causal mechanisms.

There is also limited knowledge about wellbeing and key current areas such as technology and digitalisation (e.g. artificial intelligence), climate, environmental factors such as urbanisation, the importance of proximity to nature and the cultural environment. Other key areas we need learn more about are structural factors such as reforms (e.g. the introduction of the interdisciplinary topic “Public health and life skills” in the National Curriculum), and kindergartens/schools, the working environment, social media, living conditions and various health-promoting structural measures such as changes to tax policies, access to recreational areas and regulatory changes.

The national wellbeing surveys conducted by Statistics Norway are purely cross-sectional surveys. The lack of panel data, where the same people are followed up over time weakens the opportunities to say something about causality, which and therefore makes them less useful for policymaking. There is therefore a strong need for robust research that can contribute to more knowledge to be utilised in policy decision-making processes.

Statistics Norway, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and the Norwegian Directorate of Health have all played key roles in the development of the wellbeing measurement system. There are also a number of professional communities that can contribute with research and knowledge development in various areas of the wellbeing field, such as the HEMIL Centre at the University of Bergen, OsloMet, NTNU and PROMENTA at the University of Oslo. It is also important that knowledge about wellbeing in the population is also disseminated to the population in the form of information about what can improve wellbeing.