5 Prioritisation and policy development

The National Wellbeing Strategy is anchored in the white paper on public health, Meld. St. 15 (2022–2023). The aim of the strategy is to provide direction for developing policies that to a greater extent take into consideration what is important for a good wellbeing, based on current measurements for wellbeing in the population. National and regional wellbeing measurements, together with a selection of indicators (indicator framework), could form part of the knowledge base for societal and policy design at national, regional and local level. The measurements and the indicator framework are necessary, but not sufficient instruments. The primary goal of the strategy is to ensure that society develops in a manner that equalises social differences in wellbeing and reflects what the population believes to be important for a good life.

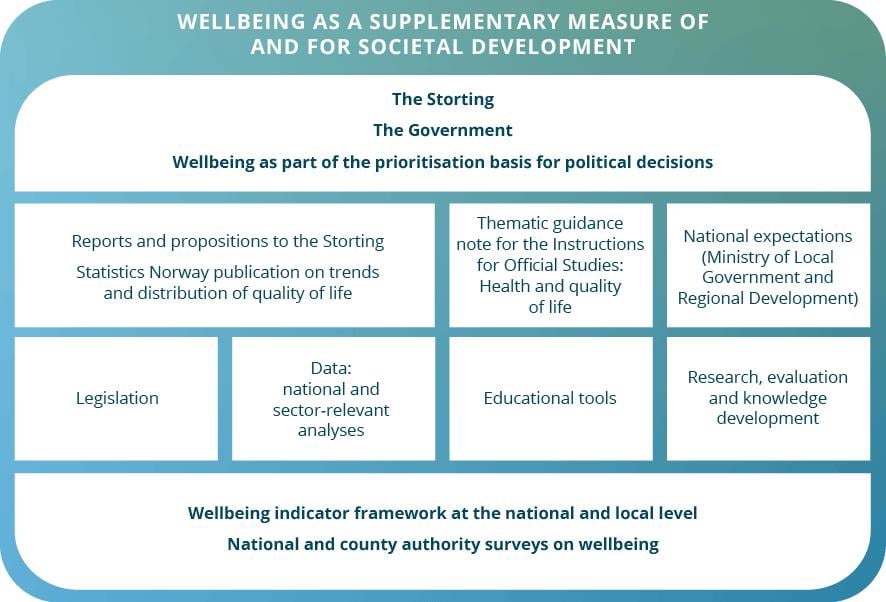

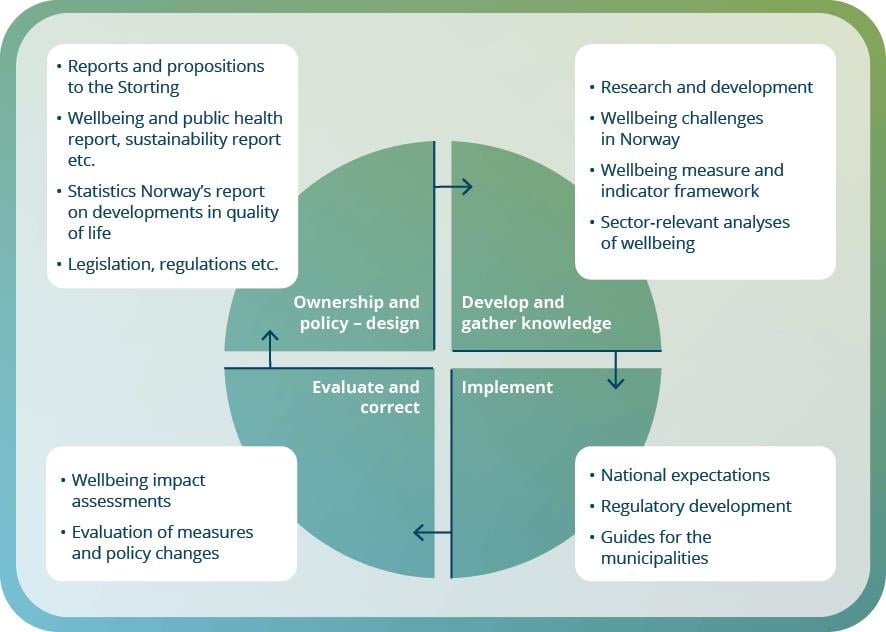

At the regional and local level, the Public Health Act and the regulations relating to public health overview with their requirements for overview efforts and links to plan strategy work, are key instruments for prioritisation and policy development. Wellbeing is now included in the Public Health Act, which was revised in spring 2025. There is no equivalent system at the central government level that can function as an instrument for prioritisation and policy development. A system will therefore be developed to ensure that wellbeing can be used across sectors and form the basis for prioritisations in national and local processes. One potential model for the government’s systematic wellbeing work is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Systematic wellbeing work at the central government level

The model is based on developing and gathering knowledge to identify wellbeing challenges in Norway through the use of wellbeing measurements, indicator frameworks and sector-relevant analyses. Initiatives to meet these challenges can be addressed when the Government, every four years, presents its national expectations for regional and municipal planning to promote sustainable development throughout the country. The county authorities and municipalities must follow up the national expectations in its plans and planning strategies. Any consequences of measures and changes must be assessed and evaluated and may lead to ownership and policy design in the form of, e.g., reports and propositions to the Storting (Norwegian Parliament), as well as revisions to legislation and regulations.

5.1 Development of an indicator framework for wellbeing

In March 2023, Statistics Norway was commissioned by the Ministry of Health and Care Services to make recommendations for an indicator framework that can be used to assess the achievement of policy goals aimed at improving the population’s wellbeing and equalising social differences in wellbeing. The indicator framework is important for gaining an overview and knowledge of social conditions that can be influenced through policymaking. The framework must also be viewed in the context of the UN Sustainable Development Goals and Norway’s follow-up of these. It will also be considered whether the framework can be linked to the instructions for official studies and reports, as well as the existing guide. This is discussed in Chapter 5.2.5 regarding instructions for official studies and reports.

In the assignment for Statistics Norway, it was specified that the framework should cover both the subjective and objective wellbeing, as well as factors that in various ways affect both an subjective and objective wellbeing in different ways (perspective on the power of influence). The framework will also include the topics of social and geographical inequality. As several studies have indicated that loneliness is one of the factors that leads to the greatest loss of wellbeing, the framework should also include loneliness. The national surveys do not include children and young people under the age of 18, and Statistics Norway was therefore asked to consider how children and young people can be addressed. In its work on the framework, Statistics Norway will also assess the extent to which data can be broken down to municipality level, or whether there is a need for a separate set of indicators at the municipal level.

The report by Statistics Norway Forslagtil et rammeverk for måling av livskvaliteti Norge [Proposal for a framework for measuring wellbeing in Norway] (available in Norwegian only) was finalised in December 2023 (1). The indicator framework contains ten dimensions and has proposed 54 indicators across these ten dimensions, including children and young people. Approximately half of the indicators can be estimated at the municipal level, but this requires some adjustments. Statistics Norway has assumed that the set of indicators must measure development over time and that it must be monitored through annual statistics. It is also emphasised that these indicators must form the basis for comparisons across geographical areas and that they can be compared with other countries, and the Nordic countries in particular. The set of indicators will highlight and present the degree of social, economic and geographical inequalities in the distribution of wellbeing.

Statistics Norway has based its choice of indicators on several important premises. The most important criterion is relevance. There should be a strong relationship between the definition of wellbeing and the choice of indicator. Other premises are outcome measures – that the indicators cover both the subjective and objective wellbeing. They must also be easy to understand and disseminate, and it must be possible to interpret changes over time as either improvements or deterioration in people’s wellbeing. The indicators must have political relevance so that they can be influenced through policy and be sensitive to changes in political decisions and the use of resources. The indicators must also enable analyses of inequality so that this can be broken down into different sub-groups, demographically, socially, economically and geographically.

Statistics Norway has chosen ten dimensions as the basis for the indicator framework: Subjective wellbeing: Health, Knowledge and skills, Finances and material goods, Physical security, Governance, participation and rights, Social community and relationships, Work and education, Leisure and culture, and Nature and local environment.

The report should be viewed as the first step in a larger body of work to develop a framework. The framework must be revised at regular intervals. There may also be a need to involve other sources of data to encompass the municipal/district levels. Work to include children, young people, the elderly and immigrants must be continued. Statistics Norway emphasises that there will be a need for a separate assessment of the relationship with the Public Health Profiles (reports that provide information on health status and its determinants in counties, municipalities, and boroughs) to ensure less ambiguity about how the wellbeing indicators and framework differ from the Public Health Profiles. Statistics Norway also believes that the framework should over time be expanded to include indicators of sustainable development and the characteristics of social institutions, as is done in New Zealand.

The current framework is extensive and complex. Through the input received, a number of suggestions have also been made for expansions to include both new dimensions and new indicators. It has also been emphasised that there is a need to ensure good data on groups that are currently inadequately covered, such as the oldest age groups, immigrants and LGBTQ+ persons. Furthermore, there has been an expressed need to go into more detail at the geographical level by providing figures for city district and living condition zones in the largest municipalities. If Statistics Norway is given the assignment to further develop the framework and indicator system, it will take these needs into account as far as possible. The interest for an expansion must be considered in relation to the available resources and the need for an indicator system that is not too extensive and complicated.

Further work should be done on methods to simplify the content so that it can, for example, be used to specific policy proposals. Consideration should be given to whether an additional dimension should be added or included in one of the other dimensions, which could take into account how international crises and conflicts may affect the population’s wellbeing.

Many countries issue publications that provide an overview of trends in the national wellbeing. Statistics Norway presents quarterly indicators for economic development in its own publication and also has a role in compiling and presenting sustainability indicators. It may be appropriate for Statistics Norway to play a similar role with respect to developments in wellbeing in Norway. In Statistics Norway’s report on the indicator framework, there is a proposal to consider a separate publication on wellbeing in Norway that could be published, for instance, every two years, and which could form the basis for an informed public debate on this development in Norway.

5.2 Methods, tools and measures: Wellbeing goals in decision-making processes across sectors

There is a need for a wide range of instruments in the process from measurements to policymaking. There is a need for a system that enables regular measurements of wellbeing to be conducted across the entire population, nationally, regionally and locally. Legislation, cross-sectoral ownership and a new guide for the instructions for official studies and reports on health and wellbeing, along with educational tools, can contribute to a policymaking where wellbeing is a supplementary measure of and for societal development. An action plan as proposed in Chapter 7 will be essential for designing concrete measures based on the strategy.

There may be a need to clarify wellbeing goals in the legislation. Data from the wellbeing surveys must be used for analyses that are relevant for policymaking at both national and local levels, and for all sectors that have ownership of and responsibility for the wellbeing goals. Educational instruments must be developed, such as in the form of guides that can be used by the municipalities. The guide for health and wellbeing in the instructions for official studies and reports (35) should be followed up to assess whether and how “Wellbeing Adjusted Life Years” (WALY – see Chapter 5.2.5) can be used for policymaking. Guidelines for the work on wellbeing should be followed up in National expectations for regional and municipal planning. Wellbeing as a measure of and for societal development can be incorporated into various reports. For example, the current white paper on public health can to a greater extent also include wellbeing, which would indicate both responsibility for and the development of public health and wellbeing in the different sectors. Wellbeing can also be more systematically integrated into other relevant reports such as the white paper on an action plan to achieve the SDGs by 2030. Statistics Norway could also produce a publication that presents developments in wellbeing and that corresponds to the publication Statistics Norway publishes for economic developments in Norway. This will, overall, give the Storting and the Government the means to make political decisions that can form the basis for prioritisations in national and local processes. A complete presentation is shown in Figure 7.

5.2.1 Systems for national and regional measurements of wellbeing

Since 2022, wellbeing has been a subject for official statistics in Statistics Norway, which aims to conduct annual surveys of the population’s wellbeing and publish selected results in Statbank Norway. The wellbeing surveys should be developed further, both in terms of coverage and non-response issues. Statistics Norway is aware that the non-response rate is significant for certain groups and has implemented certain measures, such as translating the questionnaire of the wellbeing survey into Polish and Lithuanian to reduce the non-response rate in these groups. Individuals aged 80 and above also have a relatively high non-response rate, and it is recommended to conduct non-response studies and test various measures related to data collection for the oldest age group (36). Statistics Norway notes that it may be desirable to expand its coverage for age groups by reducing the age of its respondents, perhaps all the way down to age nine. However, Ungdata has good measures of wellbeing, which can provide a source of knowledge about wellbeing among children and young people (see Chapter 4.3).

Yet certain groups will still not be included, or only partially included in wellbeing surveys, and there will still be a need for separate surveys adapted for different groups. For example, studies of wellbeing among people with cognitive impairments will require an inclusive research design with in-person surveys.

It is also essential to have a system for conducting surveys that provides data at the county and municipal levels. Fylkeshelseundersøkelsene [County Health Surveys] (available in Norwegian only) are currently conducted by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health on behalf of the county authorities, cf. Section 21 of the Public Health Act. Implementation is voluntary for the county authorities. The system must also take into account changes in societal development that may affect the population’s wellbeing.

5.2.2 Wellbeing in legislation

In several pieces of legislation, it may be applicable to include requirements with relevance to wellbeing. This could help achieve the goal of including wellbeing a measure of societal development and equalising social differences in wellbeing. The Public Health Act regulates the tasks of the central government, county authorities and municipalities to prevent disease, promote health and wellbeing and to equalise social differences. This Act entered into force on 1 January 2012. The Public Health Act was revised in the spring of 2025 and wellbeing is now included and has replaced “wellbeing” as a term. Future work must take into consideration whether other legislation should also include wellbeing. One of the prerequisites for such assessments is a progression in the professional work on the indicators.

Certain countries, such as Wales, have developed their own legislation to improve the country’s wellbeing in a number of areas: Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act (37). The Act focuses on improving the social, economic, environmental and cultural wellbeing in Wales. The aim is to “make the public bodies listed in the Act to think more about the long-term, work better with people and communities and each other, look to prevent problems and take a more joined-up approach”. The Act also operationalises the SDGs to ensure they are adapted to the national context of Wales.

Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act

The Act specifies seven clear goals for what Wales seeks to achieve through its wellbeing work: “A prosperous Wales; A resilient Wales; A healthier Wales; A more equal Wales; A Wales of more cohesive communities; A Wales of vibrant culture and thriving Welsh language”. The Act includes the government, central and local government authorities, voluntary organisations, national park authorities, fire and rescue services, cultural and sports councils, etc.

5.2.3 Cross-sectoral ownership

Wellbeing as a concept is sector-neutral and is not owned by a single sector but rather developed and maintained in all areas of society. This means that several sectors of society have responsibilities and instruments that can be combined to promote good lives for the population. An approach involving several ministries and subordinate agencies is therefore planned in the further work so that wellbeing as a goal cuts across both sectors of society and administrative levels.

The concept and work on wellbeing as part of the public health work has evolved over the past decade. Section 22 of the Public Health Act places a responsibility on central government authorities to assess consequences for the population’s health where relevant. In addition, the Public Health Act makes the Norwegian Directorate of Health responsible for providing information, advice and guidance on strategies and measures in public health work (cf. Chapter 2.6). By virtue of this role, national health authorities have previously been driving the national work on wellbeing in close collaboration with Statistics Norway and a number of research environments. The healthcare sector will continue to play an important role, but on equal footing with other sectors that are important for helping to ensure good lives for the population.

One of the most important areas to follow up towards 2030 is the further embedding of the wellbeing perspective in the social sectors. Based on sectoral analyses of the wellbeing surveys, the sectors can explore what their social mission involves from a wellbeing and distribution perspective, what initiatives and measures they have already implemented that are positive for wellbeing, and what they can do more of to promote this further. One of the most important tasks during the strategy period will be to involve the various sectors to ensure that each sector’s contribution and measures can be viewed as a whole. Measures from several sectors can be used and combined to promote a good and evenly distributed wellbeing throughout the population. For example, the voluntary sector can contribute to improving wellbeing in many areas of society and ensuring sufficient anchoring of various forms of cross-sectoral collaboration and participation processes. Voluntary organisations are key actors and meeting places for shared interests and participation in society.

5.2.4 Wellbeing in relevant white papers

A number of reports have been published that address areas that can strengthen the work on the population’s wellbeing and the goal of wellbeing as a measure of and for societal development. Among other things, it will be assessed whether to include wellbeing in:

White paper on an action plan to achieve the SDGs by 2030 The Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development presented the white paperMål med mening – Norgeshandlingsplan for å nåbærekraftsmåleneinnen 2030 (Meld. St. 40 (2020–2021)) [Meaningful goals – Norway’s action plan to achieve the SDGs by 2030] (available in Norwegian only). Work on a new white paper regarding the work on the SDGs has been initiated under the leadership of the Ministry of Digitalisation and Public Governance. Wellbeing is included as a theme together with public health in a report that is planned to be presented in spring 2025.

Public Health Report: The Public Health Report is currently published every four years and addresses a number of cross-sectoral areas that also have relevance for the wellbeing. It should therefore be considered whether the current public health report should include wellbeing to a greater extent. A joint report could be presented to the Storting every four years, and the most relevant ministers will be responsible for their own parts of the report. This would include areas such as public health, upbringing and living conditions, work and education, working environment, cultural environment, housing and local environment, social civil protection and immigration, climate and environmental challenges, culture and gender equality, agricultural policy and the aviation, road and rail sectors. It must be ensured that public health is integrated in such a way that it does not jeopardise systematic public health work. The purpose of such a report would be to promote public health and wellbeing and to equalise social differences in health and wellbeing both nationally and across sectors. In this way, we can achieve a broad anchoring and follow-up of both public health and wellbeing as measures of and for societal development. The disadvantage of such a joint message must also be considered. The public health perspective might appear to be weakened, while wellbeing as a supplementary measure of and for societal development could be viewed as part of public health work and thus not a goal in itself. A separate wellbeing report could therefore also be considered. Including wellbeing in various reports may also function as reports to the Storting.

5.2.5 Thematic guide for the instructions for official studies and reports: Health and wellbeing

“Wellbeing Adjusted Life Years is going to be the golden standard in the future”.8

The Norwegian Directorate of Health has recently prepared a thematic guide for the instructions for official studies and reports (35). The thematic guide provides specific recommendations on how life and health can be included in official reports and socioeconomic analyses in a way that ensures consistency between the various relevant units of measurement that can be used. This applies to their health and wellbeing content, as well as the economic values with which such units of measurement may be included. In this way, the thematic guide supplements the overarching guide by the Norwegian Agency for Public and Financial Management, which provides recommendations on all aspects of socioeconomic analyses (38). It is essential that the content and economic values of health and wellbeing units are consistent in order to make good and legitimate judgments on the different effects when consequences for life and health are to be weighed against other consequences of social measures.

Judgments on comparisons of the different effects involves weighing the consequences for one group of the population against the consequences for other groups of the population. These consequences may differ in both material and non-material ways and to a different extent. This makes proportionality assessments both political and challenging, and it becomes even more difficult when lives and health are affected. One challenge is that these are consequences that could have a major impact on people’s subjectively perceived wellbeing. The consequences may also be irreversible, and they have no market prices. It would also be difficult to determine any compensation and compensatory measures if someone is negatively affected.

The instructions for official studies and reports are intended to promote good decision-making and an efficient use of resources. When analysing government measures, the minimum requirement would be to always answer six specific questions. For measures that are expected to have significant effects, socioeconomic analyses must be carried out in accordance with the current circular from the Ministry of Finance (39). According to the circular, the economic value of a statistical life (VSL) is 30 million in 2012-NOK, and must be used in socioeconomic analyses within all sectors. The value of a statistical life (40) is defined as the value of a unit’s reduction in expected deaths in a given period. An estimated VSL represents a population’s (in this case Norway’s population) total willingness to pay for a risk reduction that is just large enough to be expected to save one life. When determining willingness to pay, it is assumed that the measure affects a large number of individuals and that the risk for each individual is small9. Updated figures for VSL can be found with the Norwegian Agency for Public and Financial Management10.

Another description of what VSL involves could be material consumption and all other consumption/activities that provide wellbeing, including the value of the health-related wellbeing. The phrase “overall wellbeing” is used in the thematic guide to describe what is included in VSL.

The unit of measurement to be included in socioeconomic analyses of measures affecting public health and wellbeing may vary depending on the level of precision required to capture what is important in different contexts. In many cases, the benefit of introducing measures to reduce the population’s risk of being affected by injuries or illness will be that we avoid loss of overall wellbeing.

However, there is insufficient knowledge about how the overall wellbeing can be measured in a consistent and uniform way, and how overall wellbeing is comprised of health-related and other types of wellbeing. The recommendations in the thematic guide on the choice of health unit take into account the necessity of capturing what is essential and that there is a lack of knowledge about wellbeing. A change measured in health-related wellbeing and health loss, as they included in quality-adjusted life years (QALY) and disability-adjusted life years (DALY) respectively, can be used as indicators of changes in overall wellbeing. Health-related wellbeing and health loss can be measured and are measured using recognised and widely used measuring instruments. Until a similar measurement instrument is established for total wellbeing (and components other than health that are included in total wellbeing), it is likely that QALYs and DALYs will function as useful indicators. They can then be used as a starting point for estimating changes in overall wellbeing, in cases where the risk of injuries and illness can also be assumed to result in changes in overall wellbeing. An economic valuation of these indicator health units, based on the established value of a statistical life, could provide an economic value that is relevant for use in socioeconomic cost-benefit analyses.

There are still many unresolved methodological issues, which is a concern of many other countries as well. The thematic guide is therefore based on pragmatic and preliminary recommendations on health and wellbeing units, as well as the economic values of such units. At the same time, however, the thematic guide indicates how to proceed in order to obtain more knowledge and thus be able to conduct future studies that better capture what is important for the population’s life and wellbeing.

The thematic guide refers to the overall wellbeing. This concept is also discussed in a report on wellbeing by the HM Treasury (HMT) in the United Kingdom (41). This report shows how total wellbeing can be measured and valued in a unit called WELLBY (wellbeing adjusted life years, also referred to as WALY). This value can be set to be consistent with the value of a statistical life or a value of a QALY as determined by the UK and The Green Book. The British report also refers to a number of unresolved methodological issues and it is emphasised that the economic values of WELLBY are only included as an illustration of possible use, and that these are not to be regarded as recommended values by HMT.

If in the future we wish to implement WELLBY/WALY for policymaking in Norway, it will be important to determine what is included in the concepts of overall wellbeing and health-related wellbeing respectively, as well as what is included in the established value of a statistical life. How a value of a statistical quality-adjusted life year can be calculated and used in a consistent manner in different contexts is thus also a relevant question. As the various health and wellbeing units can be given different contents, another unresolved question is what units would be most suitable for Norway (given the assumptions on which VSL is based in Norway).

The Danish Happiness Research Institute has performed WALY estimations for different life circumstances for people over the age of 50 in Denmark. These estimations showed that it is severe loneliness which leads to the greatest loss of wellbeing and number of WALYs per person per year. This is more than for depression, Alzheimer’s, other forms of dementia or unemployment. These estimations are first and foremost an example of how it is possible to use WALY in a policymaking context.

Statistics Norway’s framework for wellbeing can be assessed in relation to the instructions for official studies and reports and the current guide, and in relation to the value of a statistical life where the link to GDP is formalised.

5.2.6 Wellbeing as part of the decision-making basis for political prioritisations

“Now is the time to correct a glaring blind spot in how we measure economic prosperity and progress. When profits come at the expense of people and our planet, we are left with an incomplete picture of the true cost of economic growth” (42).

Using wellbeing in this context as part of the decision-making basis for political prioritisations means using the tools and instruments described in this strategy. These can help develop the foundation for a system that will eventually result in wellbeing becoming a measure of and for societal development.

The concept of a wellbeing economy, or “wellbeing economy” has gained increasing prominence in the work on wellbeing, and it is utilised in various contexts within the WHO, EU and OECD. There is no uniform definition of what constitutes a wellbeing economy and, according to the WHO, this must be tailored to each individual country. The WHO European Office for Investment for Health and Development has proposed a working description of the core elements of a wellbeing (wellbeing) economy:

A wellbeing economy is an economy in which public and private investments, expenditures and resources are used to improve a human, societal, environmental and economic wellbeing that can be enjoyed by all(23).

For decades, Norway has been developing a welfare model and an economy that does not differ significantly from the definition of a wellbeing economy as described by the WHO. Nevertheless, systematically using wellbeing as a measure of and for societal development could contribute to further developing the societal model and economy we have today. A societal development intended to promote wellbeing and the social equalisation of wellbeing requires key societal structures to be better adapted to ensure that they contribute to reaching this goal. The economy is one of the fundamental structures that has the greatest impact on the manner in which society is governed and organised, and Norway has solid structures to build on.

Countries that have come the furthest in developing a wellbeing economy utilise some of the same tools in this work: In a wellbeing economy, conventional economic indicators are complemented by a broad set of indicators that capture other areas of society that are important for determining whether people experience life as being good (43). Such sets of indicators can guide policy development and correspond with the indicator framework that Statistics Norway has developed for a Norwegian context.

Several countries are in the process of developing “wellbeing budgets” (wellbeing budgets). These are national budgets or parts of national budgets that also aim to promote the wellbeing of the population. Budget priorities are anchored in national wellbeing frameworks and objectives. While New Zealand launched its first wellbeing budget in 2019, Canberra is the first jurisdiction in Australia to incorporate a wellbeing framework into its budget process, launching its first wellbeing budget in 2023 (44).

Methods for including wellbeing in socioeconomic analyses have also been developed in countries such as the UK and New Zealand. There is also a Nordic initiative – Trivselsbanken/The Wellbeing Bank – in Denmark, where The Happiness Research Institute plays a key role.

Central to the wellbeing economy approach in many countries is the attempt to break down barriers between sectors of society through the development of alliances for the purpose of achieving common goals and implementing a concerted effort that benefits society as a whole, while delivering high social returns on public spending and investments (23).

Certain countries, such as New Zealand, Italy and France, have statutory requirements for knowledge about wellbeing to be reported on a regular basis. In some countries, this requirement is determined in connection with budget processes and legislation. Countries such as Scotland, Wales, Iceland, Ireland and Finland have also expressed interest in incorporating their wellbeing frameworks into their budget processes. In Norway, references to wellbeing in various reports could include regular reports to the Storting (cf. Chapter 5.2.4).

Example: New Zealand

“Wellbeing refers to what it means for our lives to go well. It encompasses aspects of material prosperity such as income and GDP. And it also encompasses many other important things such as our health, our relationships with people and the environment, and the satisfaction we take in the experience of life”.

Since 2011, the Treasury of New Zealand has developed a framework for measuring and analysing wellbeing, a Living Standards Framework (LSF). To support the LSF, the Ministry of Finance has also developed an indicator system, the LSF Dashboard. The system has a total of 103 indicators, of which 62 relate to individual and collective wellbeing and 18 to institutions, and 23 indicators measure the four aspects of national wealth.

Since 2019, New Zealand has been publishing annual wellbeing budgets, and its Treasury is required by law to publish a wellbeing report every 4 years. The Wellbeing Budget 2023 is an important source of the country’s budget information (10).

There are some common characteristics for successfully introducing a wellbeing economy. The following is based on knowledge gained from the work in Finland, Iceland, Scotland and Wales (45).

- A high-level political engagement is critical for advancing wellbeing economies both nationally and internationally. These four countries have anchored the work in the prime minister’s/first minister’s offices.

- Legislation and politically binding commitments play a crucial role in implementing policies that are in line with a wellbeing economy (e.g. the Well-being of Future Generations Act in Wales, the Fiscal policy statement in Iceland and the Community Empowerment Act in Scotland).

- Indicators and calculation systems are key to defining what is measured in a welfare economy, monitoring and informing and evaluating policies on a regular basis.

- Fiscal tools and budgeting strategies are essential for supporting cross-sectoral work and promoting co-operation and discussion between different actors such as public health bodies, and to design policies aimed at achieving the best possible wellbeing.

- Implementing innovative policy tools is key to changing and shifting to a wellbeing economy.

The Nordic Council of Ministers points out that a wellbeing economy may be better suited to meeting many of the current and future challenges and crises than current social structures (43).

The actual concept of the wellbeing economy and what it should contain is currently imprecise and there is likely long way to go before it can be used for active policies a Norwegian context. Nevertheless, the five characteristics described above could be of significance for efforts to prioritise wellbeing in important decision-making processes.

An illustration of what this might look like in a Norwegian context, and which will developed further in the action plan, is shown in Figure 7: