8 Knowledge policy

8.1 Knowledge and poverty

Education, research and technology are fundamental to social and economic development. Economic growth and poverty reduction in the west during the last century were largely due to the development of new knowledge and technology. Research and innovation have created products such as antibiotics and fertiliser, with substantial consequences for global health and food security.

A number of trends have been evident within the field of education and research in the past 20 years 1. We have seen an enormous increase in the world’s knowledge production. The expenses for research almost doubled during the 1990s 2. Furthermore, information technology, trade and migration have meant that the dissemination of knowledge is quicker than before. At the same time, the economic significance of knowledge has also increased. National and regional authorities are competing to be world leaders within research and innovation in order to ensure future economic growth, and private companies account for a steadily greater part of the research effort in the OECD area 3. The fact that knowledge has become a strategic economic resource for companies and national authorities has in turn meant that knowledge to an increasing degree is privatised and commercialised. Applications for patenting new technology have, for instance, multiplied many times in recent years. At the same time, the prices of scientific periodicals have increased considerably. Both hard copy and Internet versions of these periodicals are a main source for researchers to keep up with the knowledge development.

Figure 8.1 Exchange of knowledge and education at all levels are important prerequisites for growth and development.

The development in knowledge economics and knowledge-based competition creates both opportunities and limitations with regard to reducing the global poverty. New knowledge and technology has a large potential for improving living conditions and income potential for the poor. South Korea is one example of a country that has escaped poverty partly through a large-scale focus on education, research and technology transfers from abroad. The transfer of new technology, such as mobile telephony, can contribute directly to better living conditions for the poor (box 8.1). Mass production gives reduced costs and access to technology for groups with a small capacity to pay. A global trend towards more transparency and sharing of knowledge and technology (Open Access, Open Source, etc.) can help to ease and reduce the costs of knowledge transfer to poor countries.

Textbox 8.1 Mobile way out of poverty

Mobile telephony is an example of new technology that within a few years has gone from being reserved for consumers with high purchasing-power to being used on a large scale in poor countries. In 2000, the UN set a goal that 50 per cent of the global population shall have access to a telephone by 2015. This goal was achieved after just five years. Today almost 80 per cent of the world’s population live within range of a mobile network. Almost 60 per cent of the world’s 2.5 billion mobile phone users live in developing countries. In Tanzania, 10 per cent of the dwellings have electricity, while 97 per cent of the population have access to a mobile telephone. In Nigeria, the number of mobile phone users increased from 30,000 in 2000 to 18.5 million in 2006.

The development of mobile telephony is an example of how new technology can improve the living conditions and income potential for the poor. Mobile telephones create business opportunities. Since only very few can afford their own mobile phone, entrepreneurs can establish profitable mobile rental companies.

The use of the telephones can also contribute to increased revenue and prosperity among the poor. In Zanzibar, fish is one of the support pillars of the local economy. The fishermen now take their mobile phones with them to sea, and can obtain information on the prices of fish in different markets. Similarly, farmers can check the prices of corn, coffee and other goods in order to achieve the best possible price.

Mobile phones also have an important function in reducing costs and travelling time. This is of great value in countries where the transport system is particularly bad. Mobile phones can help to improve the service sector in poor countries. In the health services, diagnostics and follow-up of patients from remote areas are partly done over the phone. Developing banking services via the mobile network is far cheaper than building a physical infrastructure with branches and terminals, which makes the services more affordable.

World Bank (2008): Global Economic Prospects 2008: Technology Diffusion in the Developing World http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTGEP2008/Resources/complete-report.pdf BBC World Service Trust (2006): African Media Development Initiative, http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/trust/researchlearning/story/2007/02/070214_amdi_summary.shtml DFID (2006): Mobile Banking. Knowledge Map and Possible Donor Support Strategies, Report commissioned by DFID and Infordev by Bankable Frontier Associates (http://www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/mbanking-knowledge-map.pdf )

On the other hand, the poorest countries are at risk of becoming marginalised from the knowledge economy. They do not constitute an attractive market in the knowledge economy and thus knowledge and technology relevant for them are produced to an insufficient degree. Further, they cannot purchase access to new developments within medicine and agriculture that could improve their living conditions. The poorest developing countries are also trailing behind when it comes to opportunities for developing new knowledge. The Least Developed Countries have an average of 4.5 researchers per 1 million inhabitants, while developed countries have 3,300 per million. Only 0.1 per cent of the world’s total research investments are made in the poorest countries. Another marginalising factor is that the increased use of patents, licences and other types of protection of intellectual property rights also hinders the poor’s access to essential knowledge, technology and medicines. It is a major and growing problem for developing countries that Western countries register patents on knowledge and biological material that stem from developing countries lacking the capacity to use the resources commercially.

Developing countries that want to be involved in the international knowledge economy must carry out research, define research areas, educate highly qualified personnel and absorb new technology. UNCTAD claims that poor countries need to build a sufficient knowledge base, if they are to reduce their vulnerability to a liberalised global economy 4. The understanding of this has led to increased focus on knowledge policy in developing countries. One of the main topics of the African Union in 2006 was science and technology.

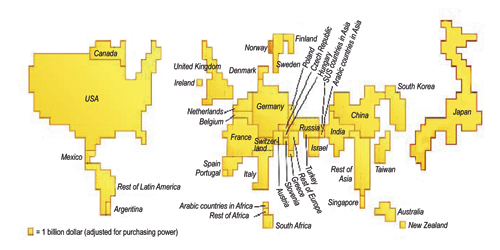

Figure 8.2 illustrates different countries and regions’ significance in global knowledge production. Developing countries such as China, India, South Africa and Brazil have gained a solid foothold as major research nations, while large parts of the Middle East and Africa are often lagging behind the rest of the world. The LDCs, with 11 per cent of the world’s population, account for 0.1 per cent of the world’s research efforts. 5 The weak knowledge base in these countries is also impaired by budget cuts and brain drain. In recent decades, the capacity in public research institutions in Africa fell by two thirds.

Figure 8.2 World measured in terms of research efforts. USD million, purchasing power-adjusted

Source UNESCO. http://stats.uis.unesco.org/unesco/ReportFolders/ReportFolders.aspx

Developing a better knowledge basis for an effective aid policy is an important area in the intersectional field between aid and knowledge policy. Donors cannot have an informed dialogue with the developing countries on effective support for their poverty reduction policies unless they themselves have knowledge of what policies can best contribute to reducing poverty in different countries and contexts. There are major statistical and knowledge gaps within the development policy, not least with regard to the main topic in the mandate of the Policy Coherence Commission – how Norway’s and other rich countries’ policies affect poor countries.

This need, which is accentuated by the need for measuring the progress of the efforts to achieve the Millennium Development Goals, is being followed up by the UN with better information in its sector organisations. Many developing countries, particularly in Africa, have however still limited access to official statistics and information as a basis for evidence based policy making. Such information and analysis is important for an enlightened public debate, not least in nation-building processes where knowledge of a country’s history etc. can be an important contribution to developing national pride. Since World War II, Norway has been a leader in the global development of statistics and economic analysis tools and has also contributed with the development of such capacity in developing countries. 6

Considerations of the Commission

Knowledge must be regarded as a global public good. Knowledge is normally created in rich countries, mainly for reasons related to finances and capacity. Statistics show that Norway to a large extent is a free rider in the knowledge area, since the contribution to global knowledge is not in proportion to the country’s value creation.

It is the Commission’s view that a knowledge policy that is coherent with the goal of reducing poverty is primarily characterised by its contribution to the production and sharing of knowledge and new technology that can improve the living conditions of the poor in developing countries. A coherent knowledge policy should also support the development of the knowledge base in developing countries and contribute with relevant knowledge on developing countries.

8.2 Policy for knowledge and technology development

8.2.1 Research aimed at the needs of the poor

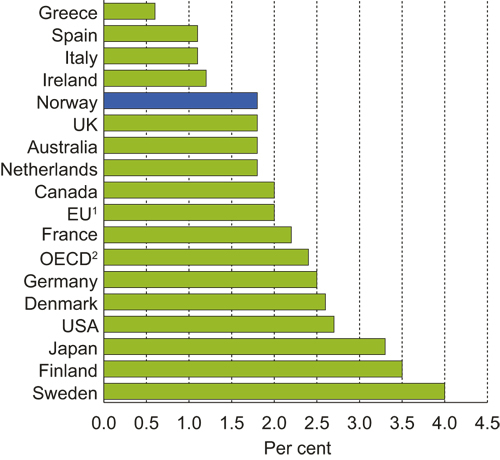

New knowledge arises when existing knowledge from throughout the world is accumulated. All countries have a responsibility to help increase global knowledge. As a small country, Norway is a net importer of knowledge, but also contributes relativelyless to the global knowledge base than most countries we draw comparisons with. Figure 8.2 illustrates how the share of GDP that Norway invests in research and development is low. The share has also fallen in recent years because the increase in the efforts has not kept pace with the GDP growth. This makes Norway a considerable free rider in the knowledge area.

Figure 8.3 Investments in R&D as a percentage of the GDP. 2003

Source OECD og NifuStep

The market will procure knowledge and technology when it is commercially profitable. This can also benefit the poor (see box 8.1 on mobile telephony). However, very little new knowledge is developed in areas where there is no market, or where the authorities or large private donors are not involved. There are few large private donors in Norway and although the developing countries to an increasing extent are attractive markets for Norwegian knowledge-based industry, this only applies to the poor part of the population to a very limited extent. Developing knowledge and technology in Norway with special relevance for the poor in developing countries is therefore dependent on public financing.

The white paper «Commitment to Research» highlighted the fact that as a rich country Norway has a responsibility to contribute to the global knowledge development. However, there is no systematic overview of status for poverty-relevant research in Norway. A survey conducted in 2007 showed that only 7.5 per cent of the health research in Norway was aimed at the major diseases in developing countries, which account for 90 per cent of the global sickness burden. The share had thus increased from 5 per cent in 2001 after global health was prioritised by the Office of the Prime Minister, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Health and Care Services. However, this is an extremely modest share considering that internationally the global share of poverty-related health research, which is 10 per cent on average, is regarded as problematically low.

The sector responsibility for research for developing countries in practice lies with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Additionally, each ministry has responsibility for financing research in its sector. There is no verification that research is carried out in sector areas which benefits poor developing countries and there are no strong incentives to do so. The reorganisation in 2004 where the management of the general bilateral aid was moved from NORAD to the embassies has led to increased fragmentation between the players and a reduced overview of the total schemes. The embassies also give very little support to initiatives within higher education and research. The reason is the lack of administrative capacity and insufficient allocations. The development-related research financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs accounts for around 2 per cent of the research financing in the national budget, or 1 per cent of Norway’s total research effort.

The EU’s framework programme for research is the world’s largest research fund and the EU’s third largest expense item. Norway takes part in the financing of the 7th framework programme, to the tune of approximately NOK 1.3 billion per annum. The framework programme places more emphasis on contributing to knowledge-building for developing countries than is the case for Norwegian research programmes, and has focus aimed at developing countries’ special needs within health, farming, fisheries and environmental protection. Norwegian researchers collaborate with researchers from developing countries in these programmes.

A range of international initiatives have been launched in areas such as health and agriculture, and Norway takes part in the financing of these. In 2001, the Commission for macroeconomics and health, which was appointed by the World Health Organisation under Gro Harlem Brundtland and headed by Jeffrey Sachs, proposed establishing a global health research fund with allocations of USD 1.5 billion per annum. This has not been realised. There are currently a number of small, uncoordinated international initiatives within health research that are not sufficient to ensure the necessary research effort (see box 8.2 on Tuberculosis). The lack of an evaluation means that there is little knowledge on the effect of the global initiatives within health research. The experiences from the international effort in agricultural research are extremely positive with regard to the effect on poverty reduction (see box 8.3). An important question is how these experiences can be developed in other relevant areas. A third area with relevance for poverty reduction is research in the intersectional field between the climate and energy. There is very little focus in this area in Norway (see details in chapter 7 on the climate and energy policy).

Textbox 8.2 Who will finance research into new medicines for Tuberculosis?

Two million people die from tuberculosis (TB) every year. A total of 8 – 9 million people are infected every year, of which 2 million are in Africa south of the Sahara. TB is caused by poverty and creates poverty. Ninety-five per cent of TB sufferers live in poor countries. When a breadwinner contracts TB it often leads to poverty for the entire family. The illness spreads quickly in poor countries with poor health systems. Poorly administered programmes have led to the development and rapid spread of treatment-resistant TB.

Despite the increasing spread and poor treatment options, there has been no progress in the treatment of TB since the 1960s. There is a need for new medicines with shorter treatment times and better diagnostics in order to be able to fight the TB epidemic. This requires research. TB research in general, and the development of new medicines in particular, is chronically underfinanced. The task to a large extent is left to the pharmaceutical industry, which is dependent on covering costs linked with research and development through the sale of products and services. The authorities’ instrument is to grant patents so that the industry can increase its earnings through high prices. TB constitutes an enormous market in terms of patient numbers, but the market size is, however, small since the number of patients that are able to pay for the treatment is small. With regard to illnesses that mainly affect the poor, patents do not entail any incentive for research and development.

In order to stimulate research into TB and other neglected illnesses, alternative incentives need to be developed that award effects on the population’s state of health.

Casenghi et al (2007) proposes developing open units for developing new medicines in collaborations between academia and the pharmaceutical industry, financed on a contract basis by the public authorities and other users. The contracts must ensure that intellectual property rights for new products that are developed do not prevent patients requiring help from gaining access to the treatment.

Casenghi M, Cole ST, Nathan CF (2007): New Approaches to Filling the Gap in Tuberculosis Drug Discovery. PLoS Med 4(11): e293 http://medicine.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.0040293 http://www.leger-uten-grenser.no/msfinternational/invoke.cfm?objectid=C4B5011D-5056-AA77-6C1AF917FFD6D314&component=toolkit.article&method=full_html

Textbox 8.3 Agricultural research reduces poverty

The Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) was founded in 1971. CGIAR is a strategic alliance consisting of a number of countries, international and regional organisations and private research funds. It is coordinated by the World Bank, FAO (Food and Agricultural Association) and UNDP (United Nations’ Development Program).

The purpose is to support 15 research institutions with a total of 8,500 employees in more than 100 countries. CGIAR has built up agricultural-related research expertise in developing countries, and among other things has developed new plant varieties that have contributed to the green revolution in Asia. Norway is one of CGIAR’s largest donors.

The CGIAR support is an extremely cost-effective use of public duties. It is estimated that each kroner invested in research through CGIAR has resulted in increased food production corresponding to NOK 9, and that this research has reduced the number of malnourished children by between 13 and 15 million.

The authorities in the middle-income countries in Asia and Latin America have increased their own efforts in this field, and CGIAR currently accounts for around 5 per cent of the publicly-financed agriculture research aimed at developing countries. Very little of the agricultural research is aimed at the African agriculture, where the problems are the greatest. The farming production in Africa has fallen by more than 10 per cent since 1980, whilst increasing by 80 per cent in Asia.

International Task Force on Global Public Goods (2006): Meeting Global Challenges: International Cooperation in the National Interest. Final Report. Stockholm, Sweden. http://www.gpgtaskforce.org/bazment.aspx

8.2.2 Contributions to building research and education environments in developing countries 7

A well-functioning system for basic education and vocational training is a prerequisite for a good recruitment basis for higher education and good-quality research. However, the focus here is on Norway’s collaboration with developing countries within higher education and research because the sector policy in this field is most relevant in a coherency perspective. The fact that the millennium development goals have led to increased international focus on aid for basic schooling is gratifying, but this effort needs to be viewed more in context with the need for a focus on higher education and research. The number of women that can read and write and go to school has been increasing for many years. New figures from the NGO network Social Watch show, however, that the positive trend has now turned. There are now more than twice as many countries in which the gender differences in access to education and literacy skills are increasing than there are in countries where they are falling 8.

Developing professionally-strong research environments and dissemination of research results are important elements of facilitating long-term economic growth, democratic development and fighting poverty. In addition to the knowledge base in the country contributing to increased international competitive power, local research, academic publishing and communication of results that is carried out by researchers with local knowledge and approaches to the problems the country faces will lead to the development of research topics that are considered to be important in these countries. Locally founded research can have greater effect in political circles and help to challenge the general understanding of the problems faced by the poor in developing countries. Researchers that also communicate results in local languages reach a wider area locally than international researchers that primarily publish in English.

«Commitment to Research» emphasised that Norway has obligations to involve poor countries in the international general knowledge through increased collaboration. Building education and research environments in developing countries requires a long-term focus of a completely different magnitude to that Norway alone can contribute with, but this does not mean that Norwegian policy in this area is insignificant. As shown in the «world map» in figure 8.2, Norwegian research focus constitutes double the total effort in the countries in Africa excluding North Africa and South Africa.

Compared with countries with a corresponding development policy, Norway appears to prioritise research and knowledge-based aid to a lesser extent. Sweden, for instance, spends about 6 per cent of its bilateral aid on research. Their experience is that focus on local institutional capacity development has given good results. This also applies to basic allocation and network support in preference to earmarked funds for research and personnel stationed in the embassies and in fields with special responsibility for research.

Commissioning parties in Norway – not least within the aid, but also other sectors – can contribute to the development of research environments in developing countries by including them in tender processes and announcements of research funds. Research environments in developing countries generally have little opportunity to take part in the competition for research funds in Norway and internationally, and the environments in the poorest countries are often of too poor quality to be able to compete. Consultants and researchers from developing countries take part in Norwegian aid evaluations primarily through hiring in Norwegian or European consultancy firms or research institutions to carry out evaluations. Norad’s evaluation department has initiated a trial in Uganda with direct recruitment by local firms.

Norwegian education and research environments can help to strengthen the knowledge base through opening up more to students from poor countries, by supporting research environments in poor countries, through research partnerships and through disseminating research results to and from developing countries. Norwegian research environments have a primary mission and a self-interest in collaborating with good research environments internationally, also in developing countries. Self-initiated collaborations between researchers in Norway and countries such as China are also on the increase.

Collaborations with research environments in developing countries that are not international leaders are not encouraged by the financing system for universities, university colleges and the institute sector, and have no research prestige attached to them. Such collaborations must therefore be financed separately. This is currently done through the research programme NUFU, which is financed through MFA/Norad with approximately equal financing from each of the Norwegian institutions that take part (which in turn are financed by the Ministry of Education and Research), and Norad’s Programme for Master Studies (NOMA). At the University of Oslo for instance, more than 100 scientific staff have project collaborations with colleagues in African countries, partly NUFU-financed, but also with funds from other sources. NUFU, which in 2003 was given a very good specialist evaluation, is however a source of moderate scope that is rather unpredictable with regard to long-term financing and involvement. A work group appointed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2007 found that four per cent of the aid goes to higher education and research. This also includes support to development research, which to a large extent consists of funds that are channelled back to Norway 9. The working group also claims that Norwegian aid only uses support for higher education and research as an active instrument to a limited degree for underpinning the activity in various sectors and focuses.

Apart from the direct allocations to universities and university colleges, programmes administered by the Research Council are the most important public financing channel in Norway. Only Norwegian research institutions can apply for financing from these programmes. In principle, research environments from developing countries can get access to such financing through collaborations with Norwegian environments. In practice, this type of participation is limited by scarce resources and political priorities of specific Norwegian problems that the appropriating ministry wants to shed light on.

One option for building research and education environments in developing countries lies in financing special collaborations with selected countries. Norway has bilateral research agreements with developing countries that are well advanced within certain research areas (South Africa, India and China). The South Africa programme is a research programme that is supported by both Norwegian and South African authorities. The Norwegian part has so far been financed from the aid budget, but will eventually be included in the ordinary research allocations. This illustrates how collaborations that have traditionally been regarded as aid are to a growing extent being regarded as equal collaborations that serve Norwegian interests. With regard to the research agreements with India and China, these are not followed up on the financing side to any great extent, despite it being in Norway’s own interest to expand the collaborations with these countries.

Multilateral financing can be more attractive for developing countries than bilateral collaborations, since the multilateral collaborations have access to more potential collaboration institutions of outstanding quality. Collaborations financed through Norwegian aid will often be tied to collaborations with Norwegian institutions that do not necessarily lead the way on the international research front in the relevant area. Both NUFU and NOMA are open for multilateral partnerships.

The majority of activities in the thematic programmes in the EU’s framework programme are open for participation from developing countries. The framework programme has developed its own instruments that are adapted to the developing countries’ capacity and Norway contributes to this through its financing of the framework programme. According to the EU, the most important limitation of the collaboration with environments in developing countries, is the poor capacity of these countries. According to the EU, more breakthroughs for developing countries in the international competition arenas for research financing require more effort from the aid side in order to develop the environments.

The research initiatives Norway supports within health and education through the UN and other multilateral organisations have little association to higher education and research institutions in developing countries. Additionally, they often have no local skills-building and institution-building as a central part of their activity and therefore contribute very little to strengthening research environments in low-income countries, which similar initiatives within agriculture do.

Norway has taken initiatives in international organisations in order to safeguard education and research environments in developing countries. In 2003, UNESCO’s general conference approved a Norwegian resolution proposal on quality in higher education. As a follow-up, the OECD and UNESCO have drawn up guidelines for quality assuring transnational higher education across country borders in order to protect students from scams and education of poor quality that has come with the increasing trade of education services.

In 2005, Norway undertook an initiative to open up the European Bologna process, whose aim is to establish a European area for higher education by 2010, to the rest of the world. Norway led the working group that devised a strategy for this. The strategy was approved at the ministerial meeting in London in 2007. Its aims include increasing the collaboration with universities in developing countries and approval of qualifications from developing countries. This initiative can probably contribute to far more focus on quality in higher education and research in developing countries than traditional aid.

8.2.3 Knowledge for a better development policy

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the main source of financing for policy-related development research. An evaluation in 2007 of the social studies part of development-related research shows that it has a large scope in Norway and that the quality is generally good. The evaluation was critical to the close connection between researchers and commissioning parties, and indicates that the aid authorities can have too much influence on which problems are researched. It was particularly noted that too little research is carried out on the effect of the aid. Another problem emphasised by a working group in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is balancing Norwegian priorities between «national ownership» and «Norwegian comparative advantages», and the importance of the use of Norwegian expertise not hindering the building of local long-term capacity and expertise.

According to the Global Forum for Health Research, 10 there is a large need for more research into implementing initiatives. This applies to many areas. Many initiatives in poor countries have often not experienced the expected effect, but due to limited research-based evaluations, we still do not know enough about why well-intended initiatives have not given better results. The focus that is now in place for achieving the millennium goals is not followed up to any great extent with the necessary research. There is also a very limited degree of coordination between the various donors, national authorities and international organisations with regard to implementation research, despite this being able to provide major efficiency gains.

Considerations of the Commission

Knowledge and technology can help to reduce poverty, but the poor do not constitute an attractive market and poor countries have no resources to prioritise higher education and research. In this perspective, the Commission regards it to be unfortunate that Norway does not focus very much on knowledge development in general, and that poverty-relevant research does not appear to be prioritised. The level of research effort is not heading in the right direction, and a steadily smaller share of the total value creation in Norway is being earmarked for developing new knowledge and technology. A slight increase in the prioritising of poverty-related health research in recent years can indicate that the prioritising has become more in line with global needs, but it is still reasonable to conclude that Norwegian research does not give much priority to the education and research needs of the poor in developing countries.

The Commission also notes that focus on developing higher education and research institutions in developing countries is modest. The Norwegian initiatives in the Bologna process and UNESCO give voice to the national educational authorities in Norway and internationally to an increasing extent taking their share of the responsibility in order to achieve the development policy goals. These are positive indications, but it remains to be seen what actually transpires from these initiatives. For the time being, it is reasonable to conclude that the intentions of the «Commitment to Research» with Norway as a global partner in the knowledge area is only followed up with definitive focus to a very limited extent.

The Commission acknowledges that there is, to a certain extent, an inherent clash between the development policy goal for research collaborations (to facilitate research capacity in developing countries) and the political goal for research collaborations (to facilitate quality and capacity in the research in Norway). However, growing numbers of middle-income countries are developing good research environments, and some also good higher education and research sectors. This helps reduce the clash between these two goals. Research collaborations can therefore be developed that help to develop the middle-income countries’ sector for higher education and research and that are beneficial to the quality and capacity in Norwegian research. This particularly applies to the collaboration with China and India, where Norway is in danger of being left behind by other more ambitious countries.

The Commission believes that research programmes and incentives in the university, university college and institute sector do not sufficiently reward research aimed at developing countries’ needs and research collaborations with developing countries with a low knowledge base. Research dissemination beyond international periodicals and in local languages that is necessary for local knowledge-building and discussion is not rewarded in the Norwegian system. In order to rectify this, the Commission believes that new stimulation schemes are needed so that the Ministry of Education and Research together with Norwegian universities, university colleges and research institutions choose to credit, prioritise and allocate more resources for research and education aimed at these needs and more global needs. It is positive that through the public university and university college institutions the Ministry of Education and Research is taking a binding participation in the financing of the NUFU programme and thereby helping to achieve the development policy goals. However, it must be emphasised that the efforts by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Research and Education and Norad are small.

The Commission believes that it will also be in Norway’s interest to establish a more global perspective on financing and prioritising. One example is health research. Infectious diseases cross country borders easier nowadays. Global warming leads to an increase in the spread of tropical diseases. In a globalised world it is therefore in Norway’s own interest to help stop the global diseases such as HIV/Aids, malaria and multiresistent tuberculosis. There is a need for a greater degree of coordination of the international effort in health research, and to involve university environments in developing countries.

The Commission believes that there is not enough research on the effect of aid. University and institute environments in developing countries are not used much in such research, which means that the synergy effects between aid and knowledge-building are not utilised.

The Commission believes that it is positive that all ministries have responsibility for research in their sectors. However, it is negative that the sector responsibility with regard to the knowledge needs outside Norway’s borders is unclear. The sector ministries are currently judged primarily on what they do «for Norway». Although the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is responsible for the development sector, it is unrealistic to expect it to bear the whole of Norway’s responsibility to contribute to knowledge-building that is relevant to the poor in developing countries. In this case, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has a far greater research budget than 1 per cent of Norway’s total research effort. A stronger Norwegian focus on knowledge and technology development for the poor will require other sector ministries to a greater extent prioritise global problems with regard to research financing. The Commission believes that all ministries should have responsibility for the global challenges within their sector and that the sector responsibility for research must be a part of this. This particularly applies to the authorities with responsibility for education and research, health, the environment, agriculture and energy and will require a long-term development with involvement and clear apportionment of responsibilities founded at a political level.

8.3 Knowledge sharing

8.3.1 Policy for copyright and knowledge-sharing

In economic terms, knowledge is a collective good or public good, characterised by being non-excluding, which means that in an unregulated market it is impossible to prevent anyone from using knowledge that is generated, and that it is non-competing in consumption, which means that someone using the knowledge does not prevent others from using it: knowledge does not get «used up» as opposed to most other goods.

This means it is profitable in economic terms for as many parties as possible to use new knowledge. There is a major benefit to society that developing countries gain access to new knowledge and technology that is mainly produced in rich countries. The fact that knowledge is non-excluding means that the financing of knowledge development is more demanding than financing most other goods. Research can either be financed from public budgets (R&D support, tax deductions etc.) or donations, or the authorities can leave it to the developer to pay. The latter will not be the case if the developer does not have any prospect of recovering his costs.

Copyright legislation aims to help those developing knowledge and technology etc. to cover their costs. The legislation gives the developer of immaterial (non-material) property exclusive, temporary right of use through patents, copyrights etc. The owner of the knowledge/technology can let others use it, normally for a charge (licence/royalty). The purpose of the legislation is to create incentives to help increase society’s access to knowledge. At the same time, the right of ownership to knowledge must not be so stringent that the positive incentive effects lead to a monopoly of knowledge. This is a key reason for patents having a fixed duration. Progress within the research requires new ideas to build on the existing knowledge. Increasing the protection of the legislation can prevent such knowledge-building and has also been shown to drain funds from research to the fight for rights in the courtroom. Monopolies also lead to artificially high prices and lower rates of innovation due to a lack of competition. The World Bank has calculated that the TRIPS agreement – the agreement on ‘Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights’, which entails developing countries that take part in the international trade agreements having to introduce copyright legislation systems on a par with those in rich countries – will quadruple the developing countries’ licence payments to rich countries, and thereby offset all development aid.

There is no research basis for claiming that more stringent copyright legislation would contribute to technological development in poor countries. On the contrary, legislation can help to prevent technological development in the least developed countries. In a survey conducted in 2007, 11 UNCTAD refers to experiences from a number of Asian countries that caught up with western countries with regard to technology development. At the technological level that many of the developing countries among these find themselves, they can copy technology from technologically advanced countries. They thus have no benefit from the technology being protected. Only at a high technological level will a country have defensive interests in protecting self-developed technology. The World Bank 12 finds evidence that copyright protection can facilitate technology transfers through direct foreign investments and establishments of subsidiaries in middle-income countries, but not in poor countries.

There is extensive agreement in the socio-economic debate that the copyright legislation in recent years has developed to favour developed countries where the rights holders are from, as opposed to the developing countries 13. In the USA and Europe, national legislation was passed that increases the monopoly power within the knowledge and technology area. Taking out a patent and patent-like protection on items that were not previously permitted to be protected in this manner has been legalised. Patents are getting increasingly longer periods of validity, and industry’s strategy is to extend existing patents by means of small changes in the patenting (evergreening). Knowledge that to a large extent is developed through publicly-financed research is patented by the business sector. The use of patents has exploded within biotechnology/genetic research, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry and agriculture. Due to increasing concerns over expensive licences in practice excluding large groups from being diagnosed and treated, the OECD has devised guidelines for licensing such innovations.

Copyright legislation in different countries is harmonised through international cooperation. It is therefore becoming increasingly easier to apply for patents in more than one country simultaneously. This leads to savings both for industry and the patent authorities, and can shorten the increasingly long processing times in the national patent offices. Long processing times delay the publishing of the research, and harmonisation can in this way facilitate the flow of knowledge. On the other hand, increased harmonisation will lead to an increase in the number of countries that each patent is valid in, which leads to more monopolising of knowledge and to developing countries losing the possibility for access and copying.

The international Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) is administered by the UN’s special organisation for World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). In the international negotiations, the USA, Japan and the EU (represented by the respective countries’ patent offices) are the driving forces behind the introduction of a universal patent, i.e. that a patent granted in one member country is automatically valid in all other member countries. In the EU, work has been underway for some time to reach agreement on a decree for a joint patent that is granted with effect for the entire EU as a whole. The process for harmonising the patent right in WIPO broke down in 2006 due to disagreement between the industrialised countries and the developing countries. After this, the negotiations were carried out in informal fora with limited transparency, and without participation from the developing countries. According to Tvedt 14 (2007), it is likely that agreement will be reached in this informal negotiation and that the negotiation results will be brought back to the WIPO as a take it or leave it solution for all countries.

The WTO’s decree through the TRIPS agreement that developing countries taking part in international trade agreements must introduce copyright legislation systems on a par with those in rich countries, will make it unlawful for developing countries to copy knowledge and technology that is patented or rights protected by foreign owners in their own country. According to the TRIPS agreement, patents should also be granted for innovations where genes and microorganisms as well as microbiological procedures are carried out. This is where the TRIPS agreement conflicts with the UN convention on biodiversity (CBD) since the granting of patents does not take consideration of the convention’s provisions that access to genetic material requires prior consent from the country from which the material emanates. According to the convention, the mutually agreed terms should also determine any distribution of the earnings from use of the genetic diversity. Under the TRIPS council, Norway has organised a new, obligatory provision whereby the origin of genetic resources shall be specified in patent protection applications. This will make it easier to ensure that CBD’s provisions are followed by those using genetic resources in developing new products.

As a result of the TRIPS agreement, all WTO countries are obliged to introduce a patent on all types of innovations, but countries are permitted not to allow patents on plants and animals. On the other hand, they are obliged to introduce a so- called sui generis system for the protection of plant varieties (article 27.3b). No close definition has been given of what such a system should be other than it must be effective. Developing countries are now being pressurised to introduce plant variety protection that is in line with the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV).

The UPOV evolved in Europe from the 1960s based on the desire to give certain exclusive rights to plant breeders and the fact that the patent system was found to be unsuitable for protecting plant varieties. The 65 current members of the UPOV are affiliated with either the 1978 or 1991 agreement. The difference between these two agreements is that the version from 1978 permits farmers to save seed grains from their own crop and use it freely. This is of great significance for farmers in developing countries. In the 1991 version, this right is restricted. Norway joined UPOV in 1993 because it was then clear that the opportunity to be affiliated with UPOV 1978 was drawing to an end. Norway is still only affiliated to the 1978 version of the agreement.

The majority of the member countries in UPOV are industrialised countries. The pressure on developing countries to join the UPOV is happening under pressure from the UPOV secretariat and from industrialised countries through bilateral trade agreements. If developing countries are to affiliate themselves with the UPOV, they must introduce national rules for plant variety protection in line with UPOV 1991, even although UPOV 1978 gives better protection for farmers’ rights to sow seeds. 15

The TRIPS agreement has a clause stating that the agreement shall be renegotiated. The developing countries have requested a speedy renegotiation, supported by Norway, among others. This has not materialised, but some changes in favour of developing countries have been introduced. Through a political declaration in 2001, the WTO agreed that the TRIPS agreement should not obstruct resolutions in the member countries to protect public health, and that all countries should have the right to issue compulsory licences in cases where public health is threatened 16. The TRIPS agreement basically restricts the power to export compulsory-licensed products, whereby developing countries without the technical or economic prerequisites to actually be able to produce duplicate medicines have in principle been referred to expensive original goods. In 2003, however, the WTO passed a supplement to the TRIPS agreement whereby medicines made under a compulsory licence can now be exported to poor countries without sufficient production capacity.

In 2005, the WTO recognised that protection of intellectual property rights can have costs that are greater than the benefits for the poorest countries. That same year, therefore, the least developed countries’ deadline to implement the TRIPS agreement was extended to July 2013. With regard to the patent of medicines, a deferment has been granted until 2016.

Due to the hiatus in the WTO negotiations, a number of bilateral and regional trade agreements are being entered into. These generally contain corresponding or more stringent (TRIPS+) requirements than the TRIPS agreement demands.

The policy in the most knowledge-intensive countries in recent years has placed more emphasis on commercialising research results. This also applies to access to international databases that are more and more closed and only made available against substantial economic contributions. Databases within health and the climate collected using financing from joint funds are to an increasing extent closed and commercialised.

This development can constitute a threat to open access to new knowledge and technology. Based on research’s vital role in solving global challenges within health, the climate, energy and natural resources, the OECD is working to ensure open access to publicly-financed research data (collected base data) and points out that the progress within such research is dependent on the broadest possible exchange and dissemination of knowledge. The European parliament has also passed resolutions to ensure that copyright legislation does not hinder the transfer of climate technology to developing countries.

Textbox 8.4 Possible negative consequences for developing countries of increased copyright protection

Empirical knowledge on copyright’s role in facilitating innovation and economic growth is limited and the conclusions are many. There are also differing opinions on the effect of copyright legislation on the developing countries’ possibilities for growth and social development. The following is a review of the negative effects for developing countries (based on UNCTAD/ ICTSD 20031, UK Commission 20022).

Economic costs: New knowledge and technology builds on existing knowledge and technology. The more available the knowledge is, the easier it is to build on it. Patents make it illegal to build on the patent knowledge as long as the patent is valid (normally 20 years), in the countries it is valid (the countries in which the patent owner has registered a patent). This can lead to the same knowledge being «invented» several times, which is a waste of resources in economic terms. Alternatively, a licence must be paid to use the patented knowledge. This increases the costs of research and innovation.

Barriers to knowledge development: Patents can be an incentive for carrying out knowledge development, but can also act as a barrier. In many industries, the technology development happens in many, small steps. This applies, for instance, within the development of software and biotechnology. When every little step is patented, maintaining an overview of applicable patents becomes resource-intensive. Companies and research environments that cannot use a great deal of resources on legal aid to maintain an overview of patents in their area risk violating patents without knowing it. There are a number of examples of companies that have fallen flat after major compensation claims for patent violations.

This affects developing countries in two ways:Industry in developing countries is more vulnerable due to poor access and resources to legal expertise. This makes the disincentives greater in developing countries where a copyright legislation system like the TRIPS agreement requires has been introduced. The production of new knowledge and technology that is especially relevant to the poor in developing countries is also affected. For example, a mass of patents on genes will make it even less attractive (more expensive) to develop medicines or seed varieties for a market with a limited ability to pay (see the UK Commission pages 127 and 129 for examples of researchers that support 39 patents in research into malaria vaccines and 70 patents in A-vitamin-enriched rice).

Pulling up the ladder: It can also be argued that developing countries should have the opportunity to copy technology in order to create economic and social development, such as Japan and South Korea have done. Both Japan and the world’s consumers are served by Toyota seeing the light of day, at the expense of American and European car manufacturers’ market power (see Dutfield 20063 for more examples, including the Swedish company Ericsson).

Prevents the poor’s access to medicine: The argument for copying technology applies generally, but the social argument is stronger within medical technology than in other industry. Generic drugs normally cost a percentage of the original. Cheap generic drugs can mean the difference between life and death for poor people. The pharmaceutical industry is working to prevent the production and export of generic drugs to poor countries (see the box on the court cases between Novartis and India).

Can threaten biodiversity and the poor’s food security: This can take place in three ways: 1) Copyright protection of plant varieties introducing economic incentives in the farming sector that will turn the production towards fewer plant varieties. The production will thereby be more vulnerable to illness. The diet of the farmers can also become more one-tracked. 2) The farmers’ options to freely exchange seeds are reduced, and they will to an increasing extent have to pay for seed corn. 3) Free exchange of plant varieties for development of new and better varieties is reduced.

Enables theft of the developing countries’ knowledge (gene robbery etc.):Extension of what can be patented for plants and other natural common biological material – with the developing countries’ having the capacity to make use of the opportunity this gives for business development – means that technologically advanced countries make off with the profit.

For example, the pharmaceutical industry has taken a patent out on traditional knowledge on curative plants etc. taken from folk medicine in developing countries. In this way, the industry earns money on the knowledge developed in poor countries, simultaneous to poor countries not having the opportunity to use their own knowledge without having to pay for it.

Makes it difficult for universities in developing countries to keep up on the research front: The main channel for quality control and dissemination of research results is articles in periodicals that are reviewed by peers. Most reputable periodicals are owned by the major international publishing houses, which have the copyright on the articles. The price increase of scientific periodicals in the past 30 years has been 3 – 4 times higher than inflation. In order for a university to be able to keep up with research, access is needed to a large and rapidly increasing number of periodicals. For universities in poor countries, the subscription costs are insurmountable. For example, the University Library at the University of Oslo spent NOK 50 million on periodical subscriptions and other media purchases in 2005. This corresponds to a third of the entire budget for higher education in Kyrgyzstan, a poor country with about the same population as Norway. Research often requires specialist software, for instance, advance statistics programmes that need to be upgraded often. The cost of many such programmes is insurmountable for many developing countries, since the licence costs are adapted to rich countries’ purchasing power. Before copyright was introduced in developing countries (often through the TRIPS agreement), software, articles and textbooks could be copied legally in these countries.

Copyright should be adapted to local conditions: Developing countries also have a need to protect knowledge and technology developed locally, and to attract foreign investors within the technology industries. Each country should find a system that corresponds to the needs of that country. However, this does not mean that it is in the developing countries’ interests to make patents and copyrights from rich countries applicable in the developing countries, as TRIPS has resulted in.

1 UNCTAD/ICTSD (2003): Intellectual Property Rights: Implications for Development. Policy Discussion Paper http://www.iprsonline.org/unctadictsd/policyDpaper.htm

2 UK Commission: Integrating Intellectual Property Rights and Development Policy. Report of the Commission on Intellectual Property Rights. London September 2002. http://www.iprcommission.org/graphic/documents/final_report.htm

3 Dutfield, Graham: «To copy is to steal»: TRIPS, (un)free trade agreements and the new intellectual property fundamentalism. Journal of Information, Law & Technology No. 1 2006. http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/law/elj/jilt/2006_1/dutfield/

Internationally, there is a growing tendency for the authorities to encourage or set requirements for publicly-financed research to be published and made freely available through archives at public institutions. This is due to steadily growing prices of scientific periodicals creating a barrier to the dissemination of knowledge. The European Research Council (ERC) decided in 2007 to require all ERC-financed research published in periodicals and requiring peer reviews (colleague assessments) to be made freely available within 6 months of publishing. The European organisation of universities (EUA) decided in 2008 to work for similar transparency for the results of research at the universities. The USA congress decided in 2008 that all research financed by the USA’s research council for health research (National Institutes of Health) shall be published on the freely available website PubMed. In 2008, Harvard University was the first university in the USA to adopt similar guidelines. A number of universities and research councils in Canada, England and China, among other places, are introducing or have introduced similar requirements 17.

Within IT there is also a relatively strong movement towards open source and free software as a reaction to trends for monopolies, patents and expensive licences in the software industry. Software that is licensed out cheaply or without charge permits the user to build further on the technology. For developing countries this can mean major savings and greater technology transfers.

8.3.2 Norwegian policy development within copyright legislation

As already mentioned, Norway spends relatively little funds on research and development. Norwegian industry also scores relatively low on international patent statistics. One reason for this is that Norway’s industrial structure has few companies within patent-intensive industries such as pharmacy and biotechnology.

In a survey conducted in 2004 on behalf of the Norwegian Industrial Property Office, a total of 91 per cent of a sample of companies from Norwegian industry reported that increased competition makes it more important to protect industrial rights 18 (Norwegian Industrial Property Office 2004). However, only 38 per cent of the companies said they will protect their own intellectual property rights. This can indicate that Norwegian companies generally have little need to protect their industrial rights.

Norway’s policy on intellectual property rights, however, has mainly followed the international trend. In 1998, Norway introduced the EU’s database directive, which gives patent-like protection for collections of existing facts. This is controversial and not permitted in the USA, among other places. In 2003, Norway decided to introduce the EU’s patent directive on the legal protection of biotechnology innovations. This further extended the definition of what can be patented in Norway. One of the arguments was that copyright protection in Europe is necessary in order to contain the low threshold that is practised in order to achieve copyright protection in the USA. Reference was also made to the fact that the business sector believed the adverse effects for Norwegian industry would be far-reaching if Norway refused to accept the directive. Major controversy surrounded the introduction of this directive. Nine out of 19 cabinet ministers, including the Prime Minister, dissented.

Some moderating measures were introduced in order to meet some of the objections to the patent directive. Among other things, the patent legislation was amended so that patent applicants had to provide details of which country the inventor received or obtained the material from. If the legislation in the supplier country requires consent to be granted for extracting biological material, the application should include details of whether such consent has been granted. However, this provision only applies to patent applications submitted directly to the Norwegian Industrial Property Office, while the majority of applications come via the PCT system. Furthermore, violating this obligation will not affect the decision on whether to grant the patent application.

In 2007, the Storting 19 endorsed affiliation to the European patent convention, which led to membership of the European Patent Office (EPO) from 2008. Through the EPO, a patentee can make the patent applicable in all countries that are members of the EPO without having to apply for a patent in each country. EPO membership invalidates some of the aversion measures mentioned above. Among other things, the duty to provide information will be easier to circumvent, so that Norwegian companies will also find it easier to sidestep their obligations in accordance with the UN convention on biodiversity and committing «gene robbery» in poor countries (see box 8.4). The civil society is concerned about the EPO’s granting of patents for common plants and animals and in Norway 16 organisations have asked the Government to intervene in an ongoing complaint in the EPO to revoke a patent for common broccoli.

As in other western countries, the Norwegian authorities are placing ever more emphasis on commercialising the research results from public universities and university colleges. The argument is mainly that the knowledge that is developed in the university and university college sector shall be made available for and used by society, but providing the university and university college sector income is also a motive. Traditionally, the universities and university colleges have stood for transparency and knowledge sharing, including with developing countries. Commercialising research results can lead to conflicts of interest in connection with transparency and sharing, but it is too early to say what the consequences of the Norwegian policy will be.

Open publishing is a major benefit for researchers at underfinanced universities in developing countries. The international trend within open access discussed above has only been used to a very limited extent in Norway. The Report to the Storting entitled Commitment to Research puts the emphasis on open access to research in Norway and the Norwegian Association of Higher Education Institutions (UHR) has recommended that the institutions follow this up, without any broad, binding follow-up taking place. Proposals were recently developed on publishing, patenting and other copyright policies for the universities and the Research Council. The proposals are characterised by the desire to protect rights as opposed to ensuring access to knowledge for society. The proposals do not take explicit account of the developing countries’ special needs for access to knowledge and technology. The Norwegian authorities are also unclear on the importance of base data as a public good, and do not make an active contribution to the developing countries gaining access to base data in key sectors. All universities in Norway have search services where knowledge is freely available. Research environments in Bergen provide research results for free use through Bergen Open Research Archive (BORA). The various search services are linked through the Norwegian Open Research Archives (NORA), which in turn is linked to international archives. However, researchers in Norway can choose whether they want to make publicly-financed research freely available. This is one key difference from the international initiatives that are presented above.

8.3.3 Norwegian policy in relation to international copyright regulations

Norway approved the TRIPS agreement in 1994. Norway has subsequently been a driving force for changing the agreement and is one of the very few industrialised countries that have tried to expedite the renegotiation of the agreement. Norway was also one of the driving forces behind the amendment to the TRIPS agreement in relation to public health in 2001 and 2003. Norway proposed a further amendment to the TRIPS agreement in 2006 which requires patent applicants to submit details of where any gene resources or traditional knowledge that the innovation is based on stems from before a patent application for this can be processed. It was also suggested in this connection that details should be given of whether the country of origin requires permission to be granted for access to the country’s gene resources, and whether such permission has been granted. This proposal could reduce the conflict between the TRIPS agreement and the UN convention on biodiversity through facilitating a fairer distribution of the benefits of using gene resources (counteracting gene robbery). An amendment to the TRIPS agreement in this area has been a requirement from a number of developing countries. Norway is the first OECD country to facilitate amending the TRIPS agreement on this point.

Textbox 8.5 Novartis vs. India

Novartis sued the Indian authorities under India’s new patent legislation from 2005, because the company wanted more stringent patent protection of its products. Novartis claimed that India’s patent legislation was not in line with the rules that were determined by the World Trade Organisation and violated the Indian constitution.

India started granting patents for medicines in 2005 in order to adhere to the WTO’s rules, but made the rules with an assurance that the patents can only be granted in cases of genuine innovations. This means that firms that apply for patents for something that has already been invented, in order to extend their monopoly on an existing pharmaceutical, will not succeed in doing so in India. It is this aspect of the law that Novartis tried to remove.

A ruling that had favoured the company would have led to a drastic reduction in the Indian production of reasonably-priced medicines that are crucial to the treatment of patients throughout poor countries. India is known as the pharmacy of the poor countries. The authorities in developing countries and international organisations are dependent on reasonably priced medicines from India. A total of 84 per cent of the Aids medicines that Doctors without Borders gives to its patients are from Indian companies.

Novartis lost the case. The court rejected all of Novartis’ objections and confirmed that the consideration to public health, which is integrated in the Indian patent legislation, is legal.

Doctors without Borders

Simultaneous to Norway’s efforts to amend the TRIPS agreement, bilateral and regional trade agreements with developing countries are being entered into in EFTA, which impose upon them a duty to introduce copyright protection beyond the provisions of the TRIPS agreement. Official Norwegian policy is not to force more stringent controls on developing countries than provided for in the TRIPS agreement. A report commissioned by the Policy Coherence Commission, however, shows that this political goal has little practical value 20. Only one out of six trade agreements that Norway has entered into with EFTA in the past five years escapes the characterisation TRIPS+ agreement. There has previously been little debate on this, and the Storting is not aware of what copyright agreements are covered by the free trade agreements since the agreements are submitted to the Storting for processing without appendices. There is an obvious conflict in this area within EFTA. Switzerland, which has strong interests within the pharmaceutical industry, has been an active driving force for extensive international copyright protection and wants more stringent patent protection in bilateral agreements as well. The Minister for Trade and Industry ensured the Storting (question time on 25 November 2007) that Norway has support for his points of view on TRIPS+ in EFTA, and that EFTA now only enters into TRIPS+ if the countries already have such agreements with other countries. Nevertheless, the survey by the Policy Coherence Commission shows that five out of six such agreements have TRIPS+ elements. There is therefore still uncertainty surrounding Norway’s and EFTA’s policies in this area. Questions should also be raised regarding the practice of entering into TRIPS+ with countries that already have such agreements regardless of the increasing pressure in developing countries for more stringent copyright protection due to the fear of trade sanctions.

The TRIPS agreement also entails an obligation for rich countries to implement national measures to transfer technology to developing countries. This provision has not worked as intended. There is disagreement on how technology transfers shall be defined. Norway reports Norad’s instruments for industrial aid and investments via Norfund as measures to transfer technology.

In WIPO, Norway has supported the USA, Japan and the EU’s wish to share the agenda in WIPO in order to progress in the process to harmonise international patent rights. A potential world patent will mean stronger ties for developing countries than the TRIPS agreement entails. The process in WIPO crosses the wishes of the developing countries. The Government has been met with criticism because the Norwegian bridge-building role between north and south is not as clear in WIPO as it has been in other fora 21 (Tvedt 2008). This can be due to Norway playing different roles in different WIPO fora. In the efforts aimed at the world patent, Norway has supported a parallel process through OECD in order to expedite the work. However, this is carried out behind closed doors and the developing countries are not included. In fora such as the WIPO working group for the protection of traditional knowledge and folklore, Norway has on the other hand had a good dialogue with the developing countries, partly to protect their interests.

After proposals from Argentina and Brazil supported by a number of other developing countries, the WIPO approved in September 2007 a «development agenda» in order to ensure a better balance between rights holders’ interests and joint interests, thereby preventing the international copyright legislation system’s credibility from being undermined. The developing countries have not succeeded in formulating a common standpoint to the development agenda. The USA, Switzerland and other rich countries have been strongly against parts of the development agenda and have claimed that if WIPO is not going to facilitate copyright legislation, the organisation no longer has a mission. There has been a great deal of antagonism between the OECD countries and a number of developing countries. Norway has not actively supported any of the parties but claims to be satisfied with the decision on the development agenda in 2007.

The World Health Organisation has appointed an «Intergovernmental Working Group on Public Health, Innovation and Intellectual Property» (IGWG), which will consider copyright legislation in relation to public health, in particular how to procure knowledge and medicines to combat overlooked illnesses, and give developing countries access to cheap medicines. Norway’s position in the WHO has been that access to lifesaving medicines (including compulsory licences if necessary) must be regarded in a human rights perspective. Norway has supported proposals to create a global plan of action, including to increase the public financing of research on overlooked illnesses. Norway has also claimed that the international copyright legislation system does not safeguard the challenges faced by poor countries, and would like to develop alternative financing schemes for health research so that patents can be avoided.

Considerations of the Commission

Norway makes an active contribution in the WTO and WHO for developing countries to gain access to new knowledge and technology. The Commission believes however that this policy is counteracted by the policy in other areas. Bilateral trade agreements and the harmonisation of patent protection put restrictions on poor countries’ access to knowledge and new technology. Additionally, the Norwegian authorities are not leaders in ensuring free access to publicly-financed research, which would be a major advantage for developing countries.

Developing new knowledge through research and innovation is an area where a small country such as Norway can make a major contribution and Norway has the right conditions for doing so. The propagation of knowledge is more complex. The Commission believes it is important that countries such as Norway contribute through aid and national and international initiatives in order to counteract the restrictions that are placed on the propagation of knowledge to developing countries. Research can increase coherence through the large potential for synergies with the development policy that exist. The copyright legislation policy can reduce the coherence by undermining the development policy goals if copyright legislation prevents the poor’s access to existing knowledge.

The Commission makes reference to the technology component of the Commitment for Development Index (CDI) to show how rich countries’ policy supports the production and sharing of knowledge and new technology that can improve the living conditions in poor countries. CDI adds positive weight to public financing and tax deductions for research, but has a negative score with regard to relations within the patent and copyright set of rules, which limits the flow of knowledge over country borders. The USA’s score is pulled down for efforts related to compulsory licensing, and European countries are given deductions for the EU’s database directive. France is in first place for spending a whole 1 per cent of the GDP on publicly-financed research. Canada is in second place for having the least restrictive copyright legislation policy of all the countries that are included in the measurement.

Norway is sixth out of 18 countries. High tax subsidies to companies for research and development (no. 4) and limited patent cover for software gets Norway a higher ranking. With regard to Government focus on research and development, Norway is average (no. 9). Norway’s introduction of the EU’s database directive, which provides patent-like protection on collections of existing facts, pulls its ranking down.

A more coherent knowledge policy will, the Commission believes, entail stepping up the public financing of research and prioritising higher poverty-related research and a strengthening of research environments in developing countries. A coherent policy for development must also to a greater extent take into consideration the fact that education and sharing of knowledge are affected by many policy areas, in addition to the education and research policy and development policy. Norway’s trade and industry policy introduces more stringent copyright legislation protection in Norway, and is involved in introducing more stringent copyright legislation protection in developing countries through WIPO and bilateral trade agreements. Norway is hereby part of a global trend, which is a disadvantage for the poorest countries. The policy development takes place in an empirical vacuum, which means that it is not well founded and the long-term consequences are unknown. Neither is the policy consistent with Norway’s role as a bridge-builder in WTO/TRIPS. The difference can be due to poor coordination between different ministries that have responsibility for their individual fields.

The Policy Coherence Commission believes in general that the knowledge policy is an area with major potential for achieving synergy effects with the development policy goals, and that higher education and research should be made into an interdisciplinary focus area. An escalation of the research effort in Norway should be combined with the development of knowledge also of relevance for development in poor countries, and particularly for the poorest population groups. Increased focus on further developing such knowledge and expertise in Norway can give Norway an advantage within new technology areas or within areas where Norway already considers itself to have a niche on an international basis. If Norway wants to have a position internationally within areas of special relevance for developing countries such as the environment, climate, energy and health, national research funds must be released in order to ensure that the Norwegian knowledge base is further developed and maintains a sufficient quality in the long term.

Commission member Kristian Norheim does not share the views expressed under paragraph 8.3.3.

8.4 Proposal for initiatives within the knowledge policy

8.4.1 Knowledge development aimed at the needs of the poor

Initiative 1: Include global knowledge needs and the developing countries’ knowledge needs in all of the ministries’ sector responsibilities for research, and in the mandates for public research institutions such as universities and university colleges.

Initiative 2: Prioritise global knowledge needs and the developing countries’ knowledge needs in the escalation of public research, particularly within health, agriculture, the climate/energy and democratisation, good governance and income distribution policies. This can be done by extending existing programmes in the Norwegian Research Council and by stimulating the university and university college sector and research institutions, as well as international initiatives (see initiative 3). At least 10 per cent of the research efforts should be targeted towards this.

Initiative 3: Lead international efforts to ensure suitable financing mechanisms that safeguard the development of knowledge and technology aimed especially at the needs of the poor. Specifically, Norway should: