4 Trade

4.1 The significance of trade on poverty reduction and development

Trade is fundamental and vital to improving human living conditions. A prerequisite for being able to trade is having something to sell. What is being traded and how it is traded are therefore crucial. Many poor developing countries nowadays have mainly raw materials to offer, which puts them in an unfavourable position in terms of trade. Raw material prices in world markets have been relatively low, while the finished goods they have had to import have been much more expensive in relative terms. A long-term development strategy is therefore dependent on the developing countries’ production of finished goods and services being strengthened in order to improve trade conditions and thereby the balance of trade.

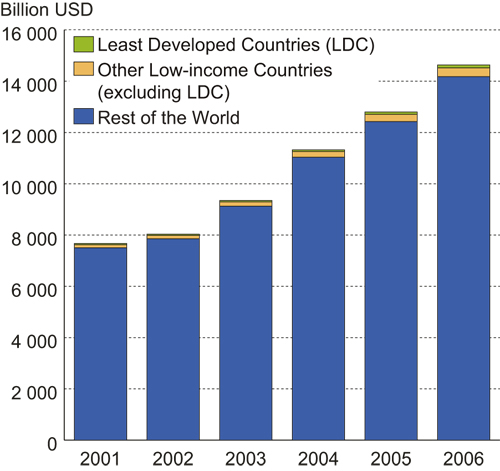

Figure 4.1 The world and poor countries’ export of goods and services 2001 – 2006

Source World Development Indicators 2007.

Recent decades have been characterised by an increase in the trade of goods and services and a more integrated global economy. This has contributed to an economic recovery and new jobs in many countries, including South Korea, India, China, Indonesia and Malaysia. China has had the most impressive development and has released more than 400 million people from extreme poverty in the last 20 years. China is one of the countries to have introduced its reforms gradually, to have phased them in according to national priorities and which due to low production costs has achieved an amazing increase in the export where the revenues have been ploughed back into the economy in order to create further growth. China has succeeded in reaping the rewards from increased market access and exports, by combining this with controlling their own economy and a national industrial policy. China has a large national market and the increased purchasing power among the Chinese has developed this market. However, growing inequality and social unrest have also been an important part of the development in China in the past two decades.

Some of the world’s poorest countries, especially in Africa, have so far been excluded from the growth in the international economy and trade. Many African countries are now experiencing considerable economic growth. Africa, south of the Sahara, has seen an average growth of around 6 per cent in recent years. Simultaneous to this, the national markets in many African countries are small and marked by low household incomes and considerable poverty. The Growth and Development Commission, which recently presented its report, 1 therefore recommends active use of trade preferences in order to contribute to this growth resulting in long-term value creation and development.

Considerations of the Commission

The Commission with the exeption of Kristian Norheim holds the view that participation in international trade is an indication of a country with capacity for value creation, employment and to finance welfare for its own population. The Norwegian society developed by combining trade and market mechanisms with a strong welfare state and the public control of parts of the economy, and through the fiscal policy, putting the surplus that is produced towards new investments and distribution of merit goods. With regard to trade, the «Norwegian model» has also been characterised by the protection of agriculture – through quotas and high duties on the import of many agricultural products – in addition to various forms of subsidies linked to the operation and sale of the industry’s products. This combination of a controlled market economy and selective protection has been a key element in the development for today’s industrialised countries.

Julie Christiansen and Kristian Norheim do not share the Commission’s view of the «Norwegian Model» as a desirable template for other countries. The common Norwegian experience is that free trade and free markets have led to considerable economic growth and that it is extremely demanding to use public regulations, including tax policies in guiding society’s resources in ways that promote growth and distribution. In particular the experience is that active use of tax policies could easily be counter productive, that tax policies are not particularly suited for active management of investment and production. A better option would be to secure the income for society through low tax rates and a broad base for taxation. Regarding trade the Norwegian variety of the Nordic model has been characterized by protection of a range of industries. As more and more industries have lost their protection it turns out that such protection has hindered development rather than advancing it. One effect from these Norwegian policies has been to encourage industries that should have restructured to instead invest disproportionally large resources in trying to achieve political protection. Christiansen and Norheim are of the opinion that selective protection has not been a beneficial element in the development of the industrial countries of today .

The Commission, with the exception of Kristian Norheim,holds that the controversy in international trade policy is about the world’s Governments pursuing different national interests, the fact that there is a fundamental imbalance in power and economic strength between rich and poor countries, and weaknesses in the international system of agreements for international trade. A joint Commission believes that there is a need for a better balance in the international trade regulations between national interests and the goals the international society have jointly set for the development policy.

Figure 4.2 World trade is growing. Shipping is important for the transport of goods.

Developing countries’ requirements for greater market access and policy space for the protection of agriculture and growing industrial and service sectors are a central part of the international trade debate. Rich countries’ protection of their agriculture markets by means of subsidies, quotas, duties and stringent health-related phytosanitary provisions, are currently preventing the developing countries from selling their products to their full potential. The hiatus in the WTO negotiations in the summer of 2008 is owing to a conflict between mainly The USA and India over developing countries’ protection of markets for agricultural products. This shows the importance of acceptance of the recognition of developing countries’ needs for both market access and policy space in the form of protection mechanisms. The Commission with the exception of Kristian Norheim is united on the assessment that there is a need for such special and differentiated treatment 2 for the developing countries. The united Commission recommends that Norway continues to base its joining bilateral and regional trade agreements on the asymmetry principle. However, the Commission is divided on its view on how extensive and permanent such agreements for special treatment should be.

Poor developing countries now have their comparative advantage in the commodities sector, and can be left behind in a primary goods producer trap. Economic history shows that a position as a one-sided exporter of commodities in the international exchange of goods keeps countries in poverty, while industrialisation and the export of processed goods creates vital positive spin-off effects 3. The Commission with the exception of Kristian Norheim believes therefore that a coherent Norwegian policy for development must prioritise contributions that give developing countries increased capacity to further develop their own industry.

The trading of foodstuff is in a unique position, despite only 10 per cent of the world’s food production cross a country border before being consumed. The World Development Report (WDR) 2008 shows that when the GDP in a developing country increases through growth in the agriculture sector, poverty is reduced at least twice as effectively as when the GDP increases due to growth in other sectors. The agriculture sector has, however, not only a special potential for reducing poverty, but also for creating economic growth in other sectors through the surplus and demand for other products that are created. Simultaneous to this, the one-sided export of agricultural raw materials is not a good strategy for promoting long-term increased growth and development. As foodstuffs have a major bearing on life and health, the issue of trade in connection with food is widely discussed.

The current high level of pressure in the food market generates major challenges for the world’s food production. The prices have continued to increase in 2008 and the majority of analyses indicate high foodstuff prices at least until 2015. However, it is important to take into consideration that the food prices before the most recent price growth have been at an unnaturally low level. A large part of the price increase is also due to increased prices of input factors such as energy and fertilizer. Although increased prices will be favourable for many of the poor who subsist on farming (given that it is these groups that benefit from the increased prices), calculations by the World Bank show that as many as 100 million people for whom these products are their most important source of nutrition, are in danger of experiencing more poverty for the same reason.

With the exception of Kristian Norheim and Julie Christiansen, the Commission believes that in a long-term development perspective, increased production capacity in general, more productive farming with a higher degree of processing, industrialisation and strengthened service production will be vital to the developing countries’ potential to benefit from trade as a development policy instrument. International, regional and bilateral trade regulations must therefore ensure market access and policy space for the developing countries to develop production capacity and through an active business and employment policy execute such adaptation processes. International trade regulations must also counter the trend for marginalising the poorest and weakest countries in the world by means of positive discrimination.

Commission members Anne K. Grimsrud, Hildegunn Gjengedal, Lars Haltbrekken and Linn Herning believe that in order to meet the increased demand for food there is a need to increase the production considerably. All countries must take responsibility and utilise their potential. Climate changes can make previous farmlands unsuitable for food production, and increased demand for bioenergy in the world market can outstrip the poor’s need for food. Additionally, consideration to climate changes and transport needs will make the global market less suitable as an arena for a reasonable distribution of foodstuff. The requirement for sustainable resource use and management of top soil and freshwater means that industrialisation and traditional intensification of the food production also have their limitations. The Commission believes therefore a much greater offensive must be pursued both bilaterally and multilaterally for the support to local producers of food and investments in order to increase the food production in poor countries.

The Commission members Hildegunn Gjengedal, Lars Haltbrekken and Anne Grimsrud hold that the hiatus in the WTO-negotiations in 2008 illustrate how important it is for developing countries to to protect their agricultural industry. India’s minister of trade said after the breakdown that developing countries cannot allow their subsistence farmers to lose their livelihood security and food security to provide market access to agricultural products from developed countries».

Commission members Kristian Norheim and Julie Christiansen believe that the liberalisation within international trade and the more predictable framework conditions that the WTO contributes to, have increased the productivity and technology exchanges between countries. Increased competition between companies has led to reduced prices and a greater choice of goods and services, as well as increased purchasing power, which benefits the consumers. World demand – including for the goods produced by developing countries – will increase and lead to growth that all nations will benefit from.

These members further believe that agricultural policy reforms by the rich countries, but also the developing countries, will be vital in order to achieve a global improvement for the world’s poor. In a development policy perspective, Norway should lead the way for a confrontation with the protectionist trade policy that exists in relation to agricultural products from developing countries. In fora such as the WTO, Norway should be a driving force in the liberalisation of trade in agricultural products through working to remove tariff barriers and direct and indirect subsidies of agricultural products. Liberalisation of the food trade will benefit Norwegian consumers, but it will especially benefit the poor, not least the poorest. In the report «Trade for development» (2006), compiled by the Task Force for Trade for the UN’s millennium project, it clearly states the importance of the developing countries also liberalising their agricultural sector and opening up their economy and markets to competition and external investment. According to the report, the OECD countries’ liberalisation and breaking down of tariff barriers will make a positive contribution to the poor countries, but the greatest gain for the poor will actually be achieved through liberalising the agriculture sector in the poorest countries themselves. A protectionist agriculture policy in the poor countries does not service the masses in these countries. Norway should not put itself in the breach for positions in the WTO that are aimed at supporting individual developing countries’ resistance to opening their own markets and internal agricultural reform in relation to the subsidy regime and tariff regime. Protectionism combined with bureaucracy and poor infrastructure is the hallmark of many developing countries today. National agricultural protectionism is not the solution, but the actual problem in, for instance, Africa. More than 70 % of the world’s tariff barriers are introduced in the actual developing countries in order to affect the trade with other developing countries. Joachim Braun, the Director General at the International Food Policy Research Institute refers to this as a «starve your neighbour» policy. Norway cannot support such a policy, even although it goes under the guise of falling under the developing countries’ «policy space».

4.2 International trade regulations

Establishing the WTO helped to strengthen the multilateral agreement regime for trade. The WTO agreement is underpinned by three pillars: the system of agreements, the dispute resolutions and the negotiation institute. The system of agreements covers three fundamental obligations: the principle of most-favoured conditions (ensures equal treatment between imported goods/services and nationally-produced goods/services) and the principle of binding obligations (ensures that obligations undertaken cannot be changed other than by negotiation).

In 2001, one year after the world’s heads of state had given their endorsement to the UN’s Millennium Development Goals, and after several previous attempts, the first round of negotiations was initiated since the start-up of the WTO. The Doha round is also referred to as the «development round», and builds on an acknowledgement that many of the poorest developing countries do not currently take part in the welfare and prosperity boost that trade can contribute to.

The three most prominent negotiation topics are agriculture, industrial products (including fish and other natural resources) and services. Norway has clear trade policy interests in the WTO negotiations. On the one hand, defensive interests: «...a new agreement shall provide us with latitude to carry out a national agricultural policy that makes it possible to keep the agriculture active throughout the country» 4. On the other hand there are offensive business interests within the service negotiations and the negotiations on industrial products, including fish.

The ministerial declaration from Doha in 2001 5 defines three criteria for development in the WTO negotiations.

Increased market access of interest for the developing countries

Balanced rules that give the developing countries policy space to implement development policy resolutions adapted to their needs and stages of development

Programmes for technical aid and assistance.

The international trade regulations have always recognised the beneficial handling of developing countries. Requirements for more beneficial treatment have been proposed since the beginning of the WTO negotiations. When political leaders from 132 countries in the global south gathered at the second South Summit in June 2005 in Doha, they formulated clear requirements for strengthening policy space:

«We must emphasise the necessity for international rules that provide policy space and flexibility for developing countries, since they have a direct effect on the development strategies of national authorities. We also emphasise the necessity of policy space for developing development strategies that take into account national interests and the different requirements of countries that are not always taken into consideration in international trade policy in the process of integrating the global economy.»

The WTO’s regulations also provide room for various preferential schemes, such as the Norwegian GSP scheme. The developing countries have also developed in UNCTAD a preferred system between themselves, GSTP, the aim of which is to develop into an international trade agreement between developing countries.

The increasingly extensive trade regulations also mean special challenges for the poorest developing countries in relation to negotiation capacity, rate of implementation and resources to benefit from the dispute resolution mechanisms.

Considerations of the Commission

A binding, rule-based multilateral trade system protects against arbitrariness, unlawful safeguards, dumping and the strongest party’s right, and is therefore important to small states as well as poor countries. Robust and balanced international trade regulations can make a positive contribution to growth, development and the reduction of poverty. The current trade regulations, however, still entail challenges in relation to developing countries’ opportunities to use trade and trade policy as part of a development strategy.

The Commission believes that a binding set of rules means that all parties relinquish parts of their own policy space in exchange for other countries doing the same. In this way, the members will jointly achieve a result that could not otherwise be achieved if all parties acted in isolation from each other. International collaboration in trade is also concerned with creating collective goods.

With the exception of Kristian Norheim and Julie Christiansen, the Commission believes that the developing countries must be ensured beneficial treatment. Where duty protection and quota protection are founded through the WTO with almost identical obligations for rich and poor countries, the developing countries are deprived of the opportunity to use the same form of protection policy as today’s rich countries used in the development of their industrial structure and economy. The main challenges are to find the right balance for the individual countries between protection and transparency – based on the country’s own prerequisites. The countries that are most marginalised in international trade have defensive interests to a large extent. Beneficial treatment will be particularly important for these countries.

When considering the marginalisation of the poorest countries, the proposals that these countries have put forward in the negotiations should be especially taken into account, and particularly the least developed countries, African countries and the group of African, Caribbean and Pacific states (the ACP countries). The developing countries, on their own and through various alliances, have expressed their dissatisfaction with the lack of progress in the development topics, which include various forms of beneficial treatment, market access, protection of own markets and trade-oriented aid (Aid for Trade). Given the marginalisation of these proposals, when interpreting the Doha round as a development round, a requirement should be added in relation to the negotiation process, transparency and participation, as this has also been a recurring requirement from the weakest parties in the negotiations.

The greatest challenge in the WTO negotiations, according to the majority of the Commission, is that it is only through expressed and active support for the developing countries’ positions that Norway can help to change the negotiation result in the developing countries’ favour.

On the developing countries’ part, criticism has been aimed at the unpredictability of the preferential schemes. The countries that give preferences are free to change or terminate the schemes. The developing countries are also afraid of losing the preferences when the general duty level falls. They partly contain safety mechanisms that put the schemes out of action when they threaten the market stability in the country that has given the preferences. A key requirement of the developing countries, therefore, is that the preference schemes must be tied to the WTO. This requirement is supported by the Policy Coherence Commission. The Commission believes that the Norwegian preference schemes must also be reviewed with a view to improvements, including the zero duty scheme being tied to the WTO. The Commission also believes that Norway should consider targeted initiatives for supporting increased south to south trade.

4.3 Negotiations on agriculture

During the ministerial conference in Doha in 2001, agreement was reached on binding and clarifying guidelines for the agricultural negotiations, including by specifying the goal for significant improvement in market access, considerable reductions in trade-oriented support and reductions for phasing out export subsidies. Agreement was also reached on taking non-trade-related conditions into account.

Agricultural subsidies in rich countries have been a key part of the WTO negotiations. There is much debate on how trade-oriented the various support schemes are, and on what are genuine export subsidies. UNCTAD is one party that claims that rich countries are to an increasing extent practising «box switching», i.e. the subsidies are maintained but change form, thereby being classified under definitions in the WTO system other than export subsidies. The EU and USA’s farming reforms are to an increasing extent based on production-dependent subsidies, and at the same time, the agricultural policy is laying the foundation for a considerable export orientation.

Textbox 4.1 Women and trade

«Women constitute the majority of the poor globally. There are many reasons for this – but what is clear is that no discussion of poverty eradication can be conducted without recognising that gender equality is a prerequisite for poverty eradication. At the Beijing Conference, the human rights of women were recognised for the first time. This constituted recognition that some human rights remain hidden from dominant discourse of the day and need to be highlighted and acted upon. For example, violence against women in the domestic sphere was given new visibility. In similar ways, decent work serves also to give new voice to the excluded – to the recognition of their rights. But it also helps in the practical business of getting people out of poverty. It is not surprising that those key areas which we focus on in the Declaration are most likely to affect poor people – and are areas we have to address in tackling poverty.

Export expansion may have potential benefits in terms of higher growth, increased employment and improved women’s welfare. But this calls for an understanding of existing structural inequities, which may undermine rather than enable sustainable human development. Unregulated import liberalisation, for instance, has threatened the livelihood of women working in formerly protected areas of the domestic economy.

Increased food imports and dumping, coupled with increasing prices for farm inputs have left many female food producers worse off than they were in the early 1980s before structural adjustment. Although some rural women farmers who were integrated in village markets have managed to increase their incomes, others have not, particularly those who could not afford to buy modern inputs such as fertiliser. Thus, even when new markets create opportunities, women are slow to take advantage of them, as they often lack access to credit.»

Elizabeth Eilor

Executive Director

African Women’s Economic Policy Network (AWPN)

With regard to the Doha negotiations, the industrialised countries have accepted favourable treatment for the developing countries through the Special Safety Mechanism (SSM) and Special Products (SP) schemes. In practice, this means that developing countries based on the SSM can introduce higher duties under specified conditions, and through SP are entitled to lower duty reductions on selected agricultural products than otherwise required. The extent and flexibility of these protection mechanisms are under discussion.

During the WTO’s last ministerial meeting in Hong Kong in 2005, agreement was reached on the phasing out of export subsidies before the end of 2013 under certain conditions. There was also agreement that industrialised countries and the developing countries that regard themselves in a position to do so, shall enable duty-free and quota-free market access for 97 per cent of the goods from the least developed countries. The full effect of the favourable trade terms will, at the end of the day, first be seen as the least developed countries improve their capacity to produce and export. The least developed countries cannot utilise complete market access initially since the importer countries have the opportunity to exempt three per cent of the tariff lines. The majority of the least developed countries have very limited numbers of export goods, and can be completely excluded from key markets due to the three per cent exemption. The least developed countries therefore want full duty and quota exemption, and for the industrialised countries to bind their duty-free and quota-free schemes in WTO. Norway introduced a zero duty policy and quota-free status for all goods from the least developed countries in 2002. This scheme was extended in 2008 to apply to all low-income countries with a population below 75 million. The zero duty scheme has a safety mechanism that will be activated in the event of major market disturbances in Norway as a result of imports.

Since the negotiations started, Norway has attached importance to the need for national production in order to secure non-trade-related considerations such as regional considerations, food security and protection of cultivated landscapes. The desire has also been emphasised to secure sustainable production through continued policy space in national policy-making. Special emphasis has been placed on the need for import protection.

Considerations of the Commission

Agriculture is particularly important in the short and medium term to many developing countries, particularly the poorest of these. The agricultural sector has major potential for reducing poverty, and many developing countries now have effective conditions for competing on the international market. The increase in international food prices gives a greater incentive to invest in and develop the production capacity in agriculture.

Figure 4.3 Trade in agricultural products is an important and controversial issue.

Since developing countries as a group are net agricultural product importers, the production should be radically increased through focus on food production. The Commission with the exeption of Kristian Norheim believes that the export focus should mainly be developed through processed farming products in order to increase the spin-off effects and growth potential in the agricultural export. Norway should undertake international efforts in order for developing countries to be able to strengthen their agriculture both for national purposes and for export.

Almost all developing countries are committed to reductions in internal support that is disruptive to trade. Both directly and indirectly subsidised exports are the source of a great deal of unreasonableness in how the international trade of agricultural products is regulated. Subsidised export is primarily a tool for rich countries and squeezes agriculture in developing countries out of international trade as well as their own domestic market.

Commission members Hildegunn Gjengedal, Lars Haltbrekken and Anne K Grimsrud believe that all countries must have the right to protect and support the production of food for their own population. It then follows that the developing countries in the WTO negotiations must be permitted to protect and develop their own agriculture, primarily for domestic markets. The national food production is key, both in the south and north. It is crucial that the set of rules in the WTO, which are aimed at regulating the approximately 10 per cent of the food production that ends up on the global market, does not incapacitate the production for local markets. A major focus on agricultural goods export from the poorest countries can affect both food security and the environment, and favour to a greater extent large and more affluent farmers, countries and companies, as opposed to the poorest farmers and countries. There is a particular danger that African women as farmers and food producers could be further marginalized.

These Commission members also want to emphasise that a Norwegian trade policy that prioritises the international reduction of poverty and more fairness between rich and poor countries has been faced with new challenges through increased recognition of global threats to the environment and food shortages. Globalisation of the markets or the most possible free trade of food and biofuels is not the answer, either to these challenges or for bringing the world closer to a sustainable and fairer world. Global food production has increased in line with the increase in population. The food shortage we face today is therefore not primarily a production crisis, but a distribution crisis. As long as we accept power centralisation and power concentration for a global market, we will not have a system that can distribute, regardless of how much production increases. The reason for this is that it is purchasing power that dictates distribution in the market, and money is what the poor don’t have. Eighty per cent of the world population currently live in countries in which the disparities are increasing. Local and national markets and ceilings under democratic control can more easily reduce the significance of inequalities in purchasing power. The right to food is one of the most important human rights. Food security is just as important as energy security. With regard to reducing poverty, it is important to ensure national and local ownership and control over the soil, the processing chain and distribution of food, and prevent it getting into the hands of multi-national companies and global economic speculators. The agricultural policy in a country has therefore more to do with distribution and the security policy than with the trade and industry policy. In international fora such as the WTO and the World Bank/IMF, Norway should support poor countries’ rights to develop food security for their own population. Unfortunately, it is these institutions that have a history of leading poor countries to believe that it is best for them to produce goods that the world market has a need for, and then to import food to its own population, in line with the free trade theory. However, the reality is increased vulnerability, lack of food and social and political unrest. Many of the poorest countries have now become net importers of food. It is time to adapt the theory to reality. With limited purchasing power among the poor of the world, it is also more profitable to use top soil and sell farming products to companies that will produce biofuels. Motorists in rich countries are willing to pay more for the product than hungry people with no money. Both food and biofuels would best be produced and distributed through small markets, primarily national and regional. Democratic control of scarce resources and fundamental needs of the population can thereby be secured more easily. Access to enough freshwater can be a bigger problem than food if the climate changes become extensive. It can, for instance, be more fair or sustainable to produce foodstuffs in Norway that require high volumes of water, instead of importing them from countries with a water shortage. Reducing poverty will always be associated with the possibility for covering fundamental needs. If the free trade philosophy is to guide the distribution of fundamental needs, the purchasing power will win and the poor will lose. Global trade regulations will be crucial to goods and services with a surplus, and with which it is natural to trade in order to achieve effective use of resources. A forward-looking set of rules in the WTO does not just lay the foundation for maximised returns through the right to conquer increasingly greater markets with others. In order to be more development-oriented, the WTO needs to safeguard frameworks and provide offers of coaching for poor countries that wish to develop their economy through domestic production and employment, in order to achieve «contest weight» so they can compete on more equal terms with others in the same «weight class». Boxing matches between «featherweight» and «heavyweight» can never be fair. Trade is an instrument, not a goal in itself, and the set of rules in the WTO must therefore be adapted to general considerations in the international community, such as the climate, fair distribution and the fight against poverty.

Commission members Kristian Norheim and Julie Christiansen point to the fact that the least developed countries account for only 1 per cent of the world trade in farming products – a share that has fallen over time. Farming, however, is a unique instrument for development and reducing poverty in a number of developing countries. Efforts to reduce the obstacles for the developing countries’ export of farming products is therefore of great significance to the fight against poverty. Norway should undertake efforts to ensure that the WTO negotiations are resumed as quickly as possible and to reduce trade barriers and enable well-functioning markets. Reducing tariff rates and subsidies within agriculture are particularly important goals. A long-term goal is to remove tariff rates on farming products. Such a policy will give farmers in the developing countries opportunities to sell their products on the global market and their efforts to increase domestic production and productivity will be strengthened. The trading of farming products and foodstuffs between developing countries has increased considerably. Through the WTO, Norway should help to strengthen this development. All forms of export support must be eliminated within the frameworks of the Doha round. Export support in the EU and other countries means a risk of products being disseminated on domestic markets, which particularly affects the developing countries.

4.4 Negotiations on industrial products, fish and natural resources (NAMA)

The NAMA negotiations have four main pillars: tariff rate cuts, linking tariff rates, removal of non-tariff trade barriers, and special protective measures and favourable treatment based on the level of development. It is further proposed that some sectors have complete duty-free status at a global level.

Norway has offensive interests in the NAMA negotiations, primarily in relation to market access for fish and fish products. The EEA agreement gives Norway zero duties to the EU on all industrial products except for fish. Some fish sales have duty relief through the EEA, but there are exceptions for some key fish sales so that general duty reductions through the WTO negotiations can have a major bearing on the Norwegian fish export. The Norwegian interests with regard to developing countries in these negotiations are connected to the major markets for industrial products in Latin America, ASEAN, plus China, Korea, Taiwan, India and Pakistan. Norway has been criticised by the NAMA-11 group 6 for making extensive demands for drastic tariff reductions in these and other countries. This is to a large extent due to the Norwegian negotiation positions within fishery also having far-reaching consequences for tariff protection in other industrial sectors. A number of contingency schemes have been created for various developing countries in the negotiations to date, and the least developed countries group is totally exempt from obligations, but there is extensive disagreement on whether the schemes are adequate to provide positive discrimination.

Many believe that it must be ensured that the fisheries – in a situation where the developing countries’ share of the world’s fish export has increased considerably – are not exclusively regarded as a manufacturing industry. In Norway, the fisheries were previously regarded as a multi-functional sector on a par with agriculture, and local fishermen had statutory preferences that helped ensure coastal development. The NAMA-11 group, which includes Namibia, believes that this function for the fisheries in developing countries should be recognised in order that the developing countries have the opportunity to use their fisheries in the same way as Norway and others have done.

Considerations of the Commission

Norway has an expressed policy to support the developing countries’ requirements and help preserve their policy space. This puts Norway in a dilemma in the NAMA negotiations. As the negotiations in principle require equally high tariff cuts in all sectors, implementation of Norwegian requirements on increased market access for fish will lead to significantly less latitude for developing countries to regulate tariff rates within all sectors. When Norway is criticised for continuing its aggressive stance towards developing countries, despite various exemption schemes, the Commission believes that opportunities should be considered to meet this criticism instead of dismissing it as wrong. A key part of such a discussion must be which countries are defined as «vulnerable» and thereby qualify for favourable treatment.

The Commission with the exeption of Kristian Norheim believes that Norway should also follow the Storting’s call to focus on the regulation negotiations on anti-dumping and non-tariff-related trade barriers instead of general tariff cuts that restrict policy space. While general tariff cuts are in the interests of the industrialised countries, non-tariff-related barriers are often key to the developing countries’ market access in the OECD countries. Market access for Norwegian fish products is also affected by non-tariff-related barriers and anti-dumping.

The least developed countries are exempt from tariff cuts in this round of negotiations, but are urged to cement as many of their tariff lines as possible. They thereby risk being affected by tariff cuts in neighbouring countries with which they have a close tariff cooperation. Despite the exemptions, they can experience increased imports of industrial goods through this tariff cooperation, which can threaten jobs, further weaken an already negative trade balance and thereby increase foreign debt. Exemptions with a view to regional development and trade are therefore an important development factor in the negotiations.

There are many debates linked to development considerations in these negotiations, in addition to the balance between restricted tariff cuts and policy space, these also include preference erosion (developing countries lose in the competition in the event of general liberalisation), loss of tariff revenues and various favourable exemptions for different groupings of developing countries.

Commission members Anne K. Grimsrud, Linn Herning, Audun Lysbakken, Lars Haltbrekken and Hildegunn Gjengedal believe that the consideration to long-term, reasonable taxation of the global fish stocks and effective management of a renewable food resource must be paramount when negotiating trade rules for fish. Norway should offer cooperation in relation to effective management, both for wild fish and farmed fish, instead of setting requirements for developing countries in the NAMA negotiations that can undermine their own production.

4.5 Service negotiations (GATS agreement)

The international trade of services has increased considerably. Efforts are therefore underway to secure an extended agreement on the trade of services based on the same basic principles for the trade of goods. The service sectors’ share of the GDP is estimated to be in the region of 1/3 in low-income countries, approximately 50 per cent in middle-income countries and around 2/3 in high-income countries. More than 70 per cent of people in employment work in the service industries. 7

Services are negotiated in a different way from the other subjects. The GATS agreement covers both general provisions for all service sectors and specific obligations for individual sectors specified in national binding lists. The negotiations are mainly aimed at increasing each country’s specific obligations, i.e. the countries bind more of their service sectors to the GATS agreement, or increase the level of liberalisation within an already bound sector. Countries have the power to exempt entire sectors or parts of sectors from obligations. The GATS agreement does not operate with favourable treatment or safety mechanisms for developing countries as with the other agreements. Efforts are currently underway to establish a least developed countries exemption, which will pave the way for positive discrimination in relation to requirements from the least developed countries. There are no exemption schemes that protect the least developed countries from requirements or obligations.

The Norwegian authorities would like to see a result in the service negotiations that strengthens the multilateral set of rules and facilitates/protects Norwegian business interests in the international competition. The key areas for Norway are shipping, telecommunication services, energy services and financial services. The authorities would also like to generally secure Norwegian industry at least equally good access to the export markets that companies’ have to the Norwegian market.

Norway has presented extensive bilateral 8 and collective demands 9 in these negotiations. For example, together with other countries, Norway has promoted requirements within energy services to countries such as Nigeria, Indonesia, Egypt, Ecuador, Brazil and Mexico in relation to liberalising the investment statutory framework/enabling investments. Norway also has requirements for the liberalisation of services with sectors such as telecommunication, energy, finance, the environment and the maritime sector.

The Government also wishes to protect development considerations in the negotiations and in 2005 decided not to set requirements for the least developed countries. Neither shall Norway set requirements for other developing countries in relation to higher education, and the supply of water and electricity.

Considerations of the Commission

With the exception of Julie Christiansen and Kristian Norheim, the Commission is concerned about the GATS agreement’s unclarified relationship to the «public sector». The agreement states that it does not cover «services that entail exercising public authority» (Art. I.3b). However, this exception is limited in a way that enables different interpretations of what can be regarded as public sector. This means there is uncertainty in relation to future interpretations of the set of rules. It may mean that services which are currently regarded as being most practical to be provided by the authorities have to be put out to tender, also to the private sector.

The majority of the Commission members believe that there are three aspects of the agreement that should be debated:

The GATS agreement’s intervention in areas that were previously regarded as national politics,

The opportunity to change policies and introduce new regulations, and

The opportunity to protect the public sector.

These elements in the GATS agreement combined with the agreement’s potential all-encompassing scope, means special challenges for developing countries’ possibilities for adapting the regulation of the service sectors in line with changes in the economy and national development strategies.

Many developing countries are sceptical to enabling foreign deliveries of basic services such as the supply of water, education, health and electricity. Some countries have enabled privatisation and the sale of such services only to discover in the next round that only the customers with the ability to pay are prioritised. These experiences show the need to preserve the latitude to change policies that have undesirable consequences for development and the reduction of poverty. The developing countries have therefore made reservations against linking such service liberalisation with renewed legitimacy.

Norway still sets requirements for service liberalisation linked to sectors such as telecommunication, energy, the environment (including waste and hazardous waste), and the maritime sector. Among other things, the requirements entail the developing countries not being able to set requirements for the use of local goods and services, restrict the share of foreign ownership in national companies or put restrictions on sending capital out of the country.

The GATS agreement intervenes in what has traditionally been regarded as national policies. Potentially, the GATS agreement, as it stands today, can enter into all areas of national services. It is also clear that it is mainly rich countries in addition to well-developed service sectors in some of the economically strongest developing countries that have an interest in and potential to utilise the international trade of services. With regard to the Doha round, the volunteer aspect in the negotiation method has been questioned since major service providers such as the USA and the EU have set stringent requirements for the liberalisation of services as a condition of an agreement.

With the exception of Håvard Aagensen, Kristian Norheim, Julie Christiansen, Gunstein Instefjord, Malin Stensønes, Camilla Stang and Nina Røe Schefte, the Commission believes that liberalisation of the investment regulations for energy services seeks to limit the opportunities for countries to set requirements for international companies on local content, national ownership shares and technology transfers. If Norway and the other proposers make a breakthrough here, this will, for instance, render impossible an oil and energy policy on a par with that adopted by Norway upon expanding the Norwegian shelf.

Commission members Julie Christiansen and Kristian Norheim believe that developing countries can be served by foreign service providers having equal access to national markets in developing countries. Services – and not least infrastructure services – play a vital role in manufacturing and other industries being able to work well, and competition from service providers from industrialised countries can help to improve and increase the number of services both for manufacturers and consumers, including from local service providers. The requirements can supply these countries with the capital and knowledge they need in order to utilise their resources more effectively and achieve more rapid economic development. Where these countries prepare for an administrative regime in the energy sector in line with that used by Norway during the development of the activity on the Norwegian shelf, it should also be possible to avoid such an opening limiting the countries’ potential to prioritise local content, national ownership shares and developing national expertise and jobs.

4.6 Bilateral and regional trade agreements

The hiatus in the WTO negotiations has led to countries with strong interests and a large capacity for negotiation attempting to find solutions through bilateral negotiations, and there has therefore been a steady increase in bilateral and regional trade agreements. More than 380 such agreements have been registered with the WTO.

These agreements have received criticism for being extremely unfavourable for the weak party where they have been entered into between very unequal parties. Agreements that have been entered into between rich countries and developing countries have a strong tendency to include agreement areas that previously have been rejected by developing countries within the framework of the WTO, or go farther than the WTO system of agreements. The problems associated with bilateral agreements that go beyond the WTO set of rules are referred to in the knowledge and investment chapters with regard to patent legislation and investment agreements respectively.

Norway primarily negotiates bilateral and regional agreements through EFTA, which as per May 2008 has 16 free trade agreements, five collaboration declarations, ongoing negotiations with six countries and three preliminary studies in progress. A new regional trade agreement between Norway (EFTA) and the South African Customs Union (SACU), consisting of South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Swaziland and Lesotho, entered into force on 1 May 2008. Through this agreement, Norway will achieve approximately the same conditions as the EU, and the agreement will ensure that Norwegian exports of goods are not discriminated against in relation to the EU in South Africa. This is also what is referred to as an asymmetrical agreement, which gives the SACU better market access to the Norwegian market than Norway gets to the SACU’s market.

Considerations of the Commission

The Commission warns against a development in which rich countries use their powers of negotiation to enter into bilateral agreements that include agreement areas that were previously rejected by developing countries in a WTO context. This is further covered in the chapters on knowledge and investment.

Development of this nature can contribute to undermining the multilateral system and can strengthen the marginalisation of poor countries in global trade, since rich countries mainly seek such agreements with the largest and richest developing countries and OECD countries.

In the tension between the bilateral agreements and the fundamental WTO principles, a debate is in progress concerning the potential to enter into asymmetrical agreements between developing countries and rich countries where the weak party is given preferential treatment. Norway and EFTA have chosen to interpret the set of rules as the possibility for asymmetrical agreements being present, ref. the EFTA-SACU agreement, while the EU has used the same paragraph as an argument to renegotiate its agreements with former colonial countries without asymmetry. The Commission believes it is important for Norway to commit itself to an interpretation of the set of rules that forms the basis for entering into asymmetric agreements.

Commission member Kristian Norheim does not share the views expressed by the rest of the Commission in the preceeding three paragraphs.

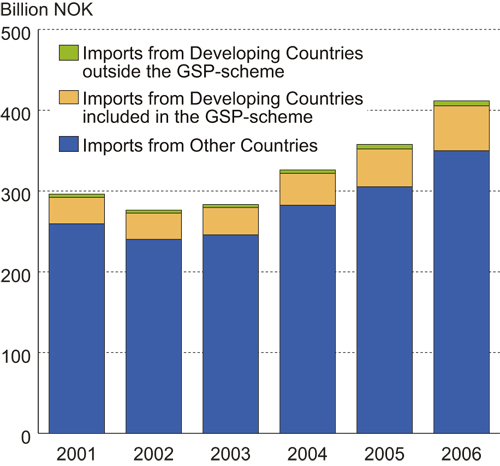

4.7 Norwegian trade with developing countries

Norway’s share of the global trade is marginal, and the trade with developing countries is no exception. Exports to Africa and South America combined are only 2.3 per cent of all Norwegian exports. Imports are mainly concentrated around industrial products, and especially textile products and clothing (around USD 250 million each) and foodstuffs (around USD 50 million). Of approximately 7,000 products that are imported to Norway, approximately 5,900 are duty free. Products that continue to be subject to duties are mainly agricultural products, some processed foods and some chemicals and textiles/clothing.

Norway imports very little from the poorest countries. Imports from the least developed countries in 2005 totalled approximately NOK 893 million, which is 0.2 per cent of Norway’s total import of NOK 357.8 billion. 10 Imports from four of the 50 least developed countries, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Equatorial Guinea and Mauritania, came to more than 80 per cent of this; approximately NOK 725 million. Imports from the remainder of the least developed countries, including all of Norway’s partner countries in Africa were consequently less than NOK 170 million; just 0.04 per cent of Norway’s total imports. The development in Norwegian imports for these 46 countries has been negative in recent years, not just as a share of total Norwegian imports but also in terms of nominal value in Norwegian kroner.

In 2005, middle-income countries in East Europe and East Asia accounted for between 10 and 15 per cent of exports of industrial goods to Norway, and these regions have increased their market shares considerably since the end of the 1980s. The market share for South America, the Middle East/North Africa and southern Africa are on the other hand less than 1 per cent, while Southern Asia is less than 2 per cent.

Figure 4.4 Total imports and imports from poor countries to Norway 2001 – 2006

Source Statistics Norway, 2008: http://www.ssb.no/emner/09/05/uhaar/tab-35.html http://statbank.ssb.no/statistikkbanken/

In 2004, Central and South America and Africa combined made up less than 1 per cent of total exports of services to Norway, main labour-intensive services within the shipping industry. Europe and North America accounted for more than 90 per cent. Once again it can be seen that despite low tariff restrictions on services, low-income countries have not achieved any great economic return from exports to the Norwegian market.

It is still within the agricultural sector that the least developed countries have the greatest production and potential for export in the short term. As with other OECD countries, Norway has highly varied market access for agricultural products, mainly with stringently regulated market access for self-produced goods and open access for non-self-produced agricultural products. Calculated in terms of calories, Norway imports approximately 50 per cent of agricultural products including sugar, but the bulk of this comes from other industrialised countries.

Norwegian imports from the least developed countries have increased in two areas. 11 The import of clothing from Bangladesh has risen from roughly zero in the mid 80s to almost NOK 413 million in 2005, and made up around half of Norway’s total imports from the least developed countries in 2005 12. Direct imports from Tanzania totalled NOK 45 million in 2005, which is a slight increase from the figure for 2000.

The Norwegian GSP scheme was last changed in 2008 when it was decided that the countries classified by the OECD/DAC as development aid recipients (referred to as the DAC list) should be covered by the zero-for-LDC scheme. A further 14 countries were thereby embodied in the scheme 13. In addition, the GSP system’s scheme, with 10 per cent tariff reduction within the WTO’s minimum access quotas for certain agricultural products, was increased to a 30 per cent tariff reduction, which among other things led to Brazil’s export quota for beef being tripled. However, this expansion does not cover low-income countries with a population of more than NOK 75 million, which excludes India, Pakistan, Nigeria and Vietnam.

Considerations of the Commission

Developing countries’ exports to Norway and other rich countries are not only restricted by Norwegian tariff barriers and non-tariff-related barriers, but also by the countries’ lack of capacity to compete in international markets. Liberalisation of tariff restrictions on imports from developing countries is therefore not often enough to guarantee either an increase in trade with or increased export revenues for developing countries. It is also necessary to strengthen the production capacity in developing countries.

The fact that Norway’s import from the poorest and most vulnerable countries is so modest is a challenge. Although Norway has had a preference in the form of zero tariffs for imports from the least developed countries since 2002, this has not had the desired effect on the import of goods from developing countries to Norway. Imports from these countries are rather insignificant. The Commission believes that the main challenge with the Norwegian schemes is that good preferences are given to countries that are not able to make use of these, while poor countries with a large potential for exploiting preferences have not been given the opportunity to do so as they do not fall under the least developed countries category. The change that was approved by the Storting in 2007 to extend duty-free and quota-free status to include low-income countries represents an important step in the right direction.

The Commission believes that predictability and taking a long-term view will be crucial to the development of competitive production in these countries and trade connections with the Norwegian market. It will therefore be important that assurance is created in relation to the enforcement of the security and monitoring mechanism linked to duty-free and quota-free imports from low-income countries, and that schemes are established to enable preferences to be linked to the WTO set of rules. Norway should to a greater extent adapt its agriculture to an increased import share of agricultural products from developing countries. The Commission further believes that due to the increased danger of a global food shortage, it is part of Norway and all countries’ global responsibility to produce food.

Commission members Hildegunn Gjengedal, Lars Haltbrekken and Anne K Grimsrud believe that the low-income countries’ low import share is primarily related to the lack of production of desired products and competitive power in the poorest countries, and preferences given to other industrialised countries, as in the EU. Norway currently imports around 50 per cent of the food we need in terms of calories, and there is a large potential for increasing the developing countries’ share of this import, without it affecting Norwegian production. By extending the current preference schemes to more countries, there is an imminent danger of the least developed countries being marginalised even further. Neither is it a goal in itself to increase the export of agricultural goods from developing countries unless this leads to a reduction of poverty. An increased focus on exports can lead to poorer security of foodstuffs, environmental problems and a further marginalisation of the poorest.

4.8 Ethical trade and fair trade

Fair trade refers to guarantees aimed at ensuring the manufacturers are paid a reasonable amount for their products. In Norway, almost all fair products are labelled Fairtrade/Max Havelaar. In 2007, sales of such products totalled NOK 38 million. This is an increase of 12 per cent from the previous year. Although the increase is considerable, the volume continues to be low. In 2006, slightly more than NOK 15 was spent per capita on fair products labelled Fairtrade/Max Havelaar. According to figures by the Fairtrade Foundation, UK consumers spent almost four times as much on such products.

Ethical trade is a collective term for socially responsible business activity that is process-oriented and which endeavours to protect human rights, employees’ rights, development and the environment throughout the value chain. The Ethical Trading Initiative Norway (ETI-Norway) was established in 2000 by Norwegian Church Aid, the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions, the Federation of Norwegian Commercial and Service Enterprises (HSH) and Coop Norway. During the ETI-Norway’s existence, ethical trade has become increasingly more topical. Commodity trade in Norway is based on goods produced in other countries to a steadily growing extent, often without satisfactory monitoring of working conditions and protection of employees’ rights. A survey conducted by Opinion and commissioned by Norad in 2006 also shows that consumers have a clear wish to act responsibly, and that ethics and responsibility are clear motivational factors when buying goods. Almost three out of four (72 per cent) say it is important for them that foodstuffs are produced in an ethical and responsible manner. Four out of five also agree that Norway should trade more with developing countries. Ethical trade therefore affects the majority of Norwegian companies either directly or indirectly.

Ethical trade has to some extent contributed to the improvement in health and safety of companies in the south 14. However, it has had little effect on areas such as freedom of association and discrimination. Employees with standard working conditions more often experience improvements than temporary employees, but it is also clear from the surveys that it is difficult to attribute improved working conditions with the ethical trade alone. Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated that it is a positive effect of a critical mass of companies following accepted standards for employment conditions, particularly when the various players in the field cooperate 15.

Fairtrade is a partnership that calls for sustainable development for excluded and disadvantaged manufacturers through better trade conditions and efforts aimed at behaviour. In order for the consumers to be able to place emphasis on ethical, social and environmental aspects, easily-accessible information on these conditions needs to be available. Fairtrade is an independent international certification scheme that gives its approval to products that are produced and traded in accordance with standards for social responsibility. The aim is to put consumers and disadvantaged manufacturers in contact with each other through a label for fair trading conditions. In this way, the disadvantaged manufacturers’ possibilities for taking control of their own future and fighting poverty are strengthened.

The public sector buys goods and services for NOK 275 billion a year. When buying goods and services the potential for reducing impacts on the environment and for promoting ethical and social considerations is high. It is therefore important which requirements the Government and local authorities set as a buyer. When definitive criteria are set for the environment and ethical/social considerations in the purchasing process, companies that supply such products and services are more likely to win the competition on equal terms. The Government has initiated efforts to devise a three-year plan of action for environmental and social responsibility in public procurements. A key part of the plan of action is the contribution to an increase in expertise and guidance on environmental and social responsibility in public procurements and mapping of what room to manoeuvre exists for setting ethical and social requirements within the current national and international rules for public procurements.

Considerations of the Commission

The Policy Coherence Commission with the exeption of Kristian Norheim believes it is important to both increase the trade with developing countries and the share that is nowadays referred to as ethical and/or fair trade. It is important to provide consumers with sufficient information on the content of the goods and on the conditions in which the goods were produced so that the individual consumer is given more opportunity to help ensure that environmental and social considerations are better protected. Reliable knowledge through, for instance, information and product labelling, can help consumers to make good choices as easily as possible.

Access to such information is however, lacking, and the Commission thinks it is unsatisfactory that Norwegian importers do not have any form of disclosure requirement to the consumers regarding the origin of the product or whether consideration has been given to the environment, human rights and the prohibition of corruption. The public sector’s purchase of goods is also considered to be important by the Commission, as there is a considerable potential to facilitate ethical and social considerations in the choice of suppliers.

Commission member Kristian Norheim believes that free trade is fair trade and that ‘Fairtrade’ is not fair. The majority of producers in developing countries will not benefit from rich white people trying to launder their conscience by purchasing products branded as produced in a fair or ethical manner. Large scale prosperity is created by genuine economic growth and development. Instead of promoting poverty reduction by investing in small scale trade projects Norway should support policies that open up world markets to all producers in developing countries and not only favours the tiny minority who have been fortunate enough to obtain a ‘western’ mark of approval on their products. Token policies cannot save the world’s poor. Norway should abstain from such policies and give Norwegian consumers the opportunity to buy more goods from developing countries as well as stimulate them to do so instead of using customs barriers or indirectly frightening Norwegian consumers through campaigns such as the «Norwegian products for Norwegian consumers» by the Foundation KSL Matmerk (foodbrand) set up by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food in 2007.

4.9 Travel and tourism

Tourism is one of the strongest growing industries in the world. Tourism is ranked as the third largest sector in the economy of more than 50 of the world’s poorest countries. Every third tourist in the world travels to developing countries. Only a small proportion of these go to southern Africa, but the region has the quickest growing tourist industry in the world. Tourism is a labour-intensive sector in which developing countries have a comparative advantage. In many countries, travel and tourism give the world’s poorest populations more legs to stand on. Work and increasing incomes of people living in the tourist destinations make a positive contribution to the reduction of poverty through the supply of goods and services, both in the travel destinations and through external effects such as the development of infrastructure.

Although tourism can contribute to growth and welfare for large numbers, poorly regulated tourism can result in overburdening vulnerable areas, deterioration of the environment and the destruction of biodiversity. Existing and potential tourist attractions can therefore be affected in a way that has an impact on earnings and can also therefore be harmful to the economic development. It can also be seen in certain areas that the developing countries retain very little of the tourist revenues. There are examples from the Caribbean that show that 70 per cent of all tourism revenues leave the country: the tourists use imported goods, the hotel chain owners get most of their supplies from abroad and the capital that is injected is foreign. Another challenge faced by poor tourist areas is an increase in prostitution and trafficking.

Figure 4.5 Many developing countries have a large potential for sustainable tourism.

International tourism has changed in the past 10 years in line with the heightened awareness of sustainability and the socio-cultural, economic and ecological effects of tourism. Both the supply and demand for tourism have received impetus from studies 16 that have shown that by combining the protection of natural areas with tourism, we can help preserve the local environment, at the same time strengthening local industry and thereby helping to reduce poverty. Many of those marketing themselves under the banner sustainable tourism claim to make a positive contribution to the local economy and to protecting and raising awareness of the environment and cultural heritage where they operate. The UN’s attitude-forming efforts have been very important with regard to affecting the industry. The UNWTO and the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) have given positive impetus to the industry and the UN’s TOI (Tour Operators Initiative for Sustainable Development) is uniting a number of major tour operators to work towards sustainable strategies for tourism. The UN resolution on sustainable travel and the Global Code of Ethics for Tourism are other examples of important initiatives that act as guides for the tourism industry as regards sustainable tourism.

A more cultivated form of sustainable tourism is the so-named ecotourism. In 2004, ecotourism grew three times as fast as the tourism industry as a whole, and a market analysis by the GRIP foundation (Green in Practice) indicates that as much as 11 – 22 per cent of the population in western countries may be interested in taking part in this type of tourism. 17 However, the concept has been criticised by, among others, The Pro-Poor Tourism Partnership, which was formed by the DFID in 1999 18 and which believes that ecotourism gets too much attention in relation to mass tourism, for example, which can have a greater potential to reduce poverty.

GRIP has contributed to the development of the ecotourism alliance known as African Ecotourism Alliance. Such alliances can both help to transfer expertise and information, as well as provide advice on requirements, guidelines, quality labelling and relevant international conventions. Expertise can also be transferable in cases where the local community is faced with difficult negotiations with foreign investors wanting to focus on tourist development. Such organisation and network-based gathering of knowledge and sharing experiences on a south-to-south basis should be supported by the Norwegian authorities.

Considerations of the Commission

For more than 50 of the world’s poorest countries, travel and tourism are already ranked as the first, second or third largest sector in the countries’ economy. The potential for further strengthening travel is, however, considerable in many countries. Simultaneous to this, it will be important to try to strengthen a sustainable tourism industry, which both contributes to reducing poverty and preserving the environment and culture whilst being a possible source of mutual understanding and respect between cultures.

Many consumers are willing to accept a higher price in order to ensure that the travel they purchase has a social and environmentally-friendly profile. Sufficient and reliable information, quality labelling and marketing are, however, crucial to the consumers being able to find their way in the market and for helping to change attitudes in such a way that the players choose the best alternatives from an ethical perspective. The authorities can provide such information in order to facilitate social responsibility and good ethical choices.

Increased awareness in the tourism industry and among consumers of positive and negative effects of tourism will hopefully mean more development effects from tourism. The Commission wishes to place emphasis on the importance of local spin-off effects through local employment, purchasing and ownership. By using local input factors and raising the awareness of conditions related to employment, the environment and production, the tourism industry could increase the positive development effect of its activity.

Commission member Kristian Norheim does not agree with these views by the Commission majority.

4.10 Proposal for initiatives within the trade policy

In line with the Commission’s considerations, there is potential in a number of areas for modifying the Norwegian trade policy in a more development-friendly direction. The Commission recommends that the Norwegian authorities construct a more development-friendly trade policy based on the following three pillars:

International trade rules that strengthen the developing countries’ possibilities and ensure the necessary policy space.

A Norwegian trade and trade policy that prioritises the considerations to development.

A consumer policy that facilitates ethical and fair trade.

4.10.1 International trade rules that strengthen the developing countries’ possibilities

The Commission recommends that greater emphasis is placed on development aspects in shaping Norwegian negotiation positions in the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Norway needs to place emphasis on both market access and policy space for developing countries in the negotiations. Steps in this direction will include the following:

Norway must work actively in order to make the developing countries’ positions visible and for formalised rules for transparency, participation and representation in the negotiations that provide marginalised countries with a better basis for negotiation. The Government should regularly submit a white paper on the WTO negotiations in which the development perspective is pivotal. The Minister of the Environment and International Development should be involved actively in the shaping of Norwegian negotiation positions in the WTO.

With the exception of Kristian Norheim and Julie Christiansen, the Commission believes that Norwegian exports of fishery and seafood products must not be forced at the expense of developing countries’ possibility for the tariff protection of manufacturing and sea industry sectors. Norway must therefore reduce its requirements for market access in developing countries within the NAMA negotiations. Norway must also pursue and support the efforts with various exemptions for developing countries in the NAMA negotiations, in order to ensure positive discrimination for the developing countries and the potential for a longer period to protect sectors and industries under development.

With the exception of Kristian Norheim, the Commission believes that in the NAMA negotiations in the WTO, Norway should work to strengthen the set of rules for anti-dumping within the fisheries industry since this is an important matter for many developing countries.

With the exception of Kristian Norheim and Julie Christiansen, the Commission believes that water, health and education should not be sectors that are subject to the GATS regulations, but be protected with a view to future generations’ possibilities for regulating these basic services for the good of the population. Norway should strive for a clarification and extension of the definition of public services, which secures the opportunity to protect these from the negotiations.

With the exception of Kristian Norheim, Camilla Stang, Malin Stensønes and Julie Christiansen, the Commission believes that an extended WTO set of rules for services must contribute to clear and predictable rules for the international trade of services, but must not impede developing countries’ possibilities for developing competitive players/companies within the service sector. It is therefore recommended that Norway strives for the necessary flexibility in the set of rules, with possibilities for national handling, and that Norway does not require liberalisation in developing countries that entails phasing out of business policy instruments such as positive discrimination of and subsidies to national service providers/players/companies. This particularly applies to sectors such as telecommunication, energy and financial services.

With the exception of Gunstein Instefjord, Håvard Aagensen, Malin Stensønes, Camilla Stang, Nina Røe Schefte, Kristian Norheim and Julie Christiansen, the Commission believes that within the GATS negotiations, Norway should not require the liberalisation of mode 3 (investments/establishment/commercial presence), since this puts restrictions on a country’s potential to use political instruments, for instance, requirements for local labour or local input factors, which can contribute to long-term development. (See also initiatives on bilateral investment agreements.)

The Commission recommends that in the WTO, Norway strives for the greatest possible reduction of both direct and indirect export subsidies. The Commission recommends that a critical review is undertaken of all Norwegian subsidy schemes in light of this.

With the exception of Kristian Norheim and Julie Christiansen, the Commission believes that Norway should strive for developing countries being given the opportunity to use import protection in order to protect and develop their own agriculture. Among other things, this entails Norway actively supporting the developing countries’ requirements associated with special safety mechanisms and protection of special products.

Norway should work to strengthen the predictability of the preference schemes by these being bound in the WTO system. It is recommended that pending a set of rules for binding preferences, Norway makes a binding declaration on the binding of its own preference schemes and challenges other countries to do the same.

Norway should work actively to strengthen developing countries’ potential to make use of the dispute resolution mechanism. This entails Norway having to oppose every exemption from the use of the dispute resolution mechanism (previously known as the peace clause) unless it applies to very limited negotiation periods.

4.10.2 Bilateral trade agreements that emphasises development considerations

With the exception of Kristian Norheim and Julie Christiansen, the Commission recommends that Norway places emphasis on asymmetrical bilateral and regional trade agreements that give benefits for developing countries both with regard to market access and protection rights.

When signing bilateral or regional trade agreements, Norway should respect the multilateral system and not include topics that have been rejected by the WTO unless this is a request from developing countries. Special rules apply for investment protection and TRIPS+ elements. (Investment agreements are covered in the investment chapter and TRIPS in the knowledge chapter.)

Norway should include exemptions and protection mechanisms in its trade agreements that can develop and strengthen national production and service sectors in developing countries.

4.10.3 A Norwegian trade policy that prioritises development considerations