3 A coherent policy for development

3.1 The vision

The Policy Coherence Commission believes that the rich part of the world has a special responsibility to be aware of the consequences for developing countries of what in principle is regarded as a national political path. Developing countries are particularly vulnerable to decisions made outside their own country borders. Norway has also acknowledged responsibility for contributing to value creation and the reduction of poverty in these countries through the UN Millennium Declaration, among other things. This does not mean that the Commission believes that all developing countries at all times have identical interests, or that these countries should be deprived of the opportunity to take responsibility for their own political path, but that we in Norway and abroad should help to remove obstacles that we and other parties are responsible for and which prevent them from taking part in the international community on at least equal terms as us.

The need for a more coherent policy for development emanates from the fundamental, mutual dependency that to a growing extent is characterising all policy areas, both in Norway and abroad. The framework conditions for national policies, including in Norway, have changed in almost all areas as a result of international trends, power structures and development features. Similarly, several aspects of Norwegian policies are affecting framework conditions and development opportunities for political authorities in other countries to a steadily increasing degree. The Commission uses the following definition of a coherent policy for development (the OECD’s definition):

« Policy Coherence for Development (PCD) means working to ensure that the objectives and results of a Government’s development policies are not undermined by other policies of that Government, which impact on developing countries, and that these other policies support development objectives, where feasible.»

Combating poverty, through aid and other means, is an ethical imperative for many. However, there are a number of reasons why poverty should be combated. In a globalised world, reducing the number of poor is a wise investment in a common future. Fewer poor people means that more will be in a position to take part in global economic and cultural interaction, fewer will be motivated to take part in conflicts and more will be able to contribute to measures against the deterioration of the environment. Addressing poverty has both an intrinsic value and is crucial to creating a better common future.

Reducing poverty is closely linked to economic growth and distribution. Economic growth can also have negative effects on global public goods, for example in the form of the deterioration of the environment. A global public good is something that in principle everyone can benefit from and for which the value and significance for each individual is not reduced even although everyone else uses it 1. There are only a few «pure» global public goods according to this definition, but peace and security, protection against and prevention of the spread of epidemics, financial stability and fundamental human rights, a stable climate, free access to knowledge, opportunities to travel freely and globally agreed rules on trade and investment, all have characteristics of such goods. The condition of these goods is vital to the development in all countries and their inhabitants. A joint task for both rich and poor countries is therefore to strengthen the production of the global public goods and ensure that as many people as possible can benefit from them.

Textbox 3.1 Global public goods

«Global public goods which will benefit developing countries (and Norway) are heavily underfinanced. At the same time, there are sources of significant (global public) finance in the form of excess and underutilized capital at International financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank (WB) amounting to as much as USD 100 billion. Norway should spearhead the international effort to allocate this money towards the provision of scarce global public goods and such an effort will produce significant positive outcomes for developing countries without any additional cost to Norway.»

Sony Kapoor, head,

International Finance, Environment & Development Consultant (India, UK, Norway)

Poor countries do not always have the same prerequisites as rich countries to utilise global public goods. Power is systematically unevenly distributed between countries, and makes some countries dependent on framework conditions set by others. The latitude for action afforded to developing countries is, therefore, often extremely limited. These limitations can have historical reasons, and be due to structures and the division of labour established in the world during the colonial period; they can also be due to poor countries’ debt burden, and dependency on donors in rich countries or multilateral financial institutions; to the fact that markets in which countries in the north can freely sell their goods are closed to the poor in the south; conflict, either civil conflicts or military dominance from beyond country borders are also key reasons for a lack of development many places in the world. Climate change has an extremely adverse effect on poor countries, despite the historical responsibility for the greenhouse gas emissions mainly lying with the rich countries. Many poor countries can also not benefit from scientific progress in relation to health since the population cannot pay enough since medicines are patented or because too many medical personnel have emigrated. In many countries investors are nowhere to be seen and local capital is invested abroad due to poor legal facilities and administration systems, crime and corruption. A lack of potential and growth in poor countries can therefore be due to external conditions, their position in the global distribution of power and work, and internal problems related to governance.

Successful aid can help poor countries address problems that are due to various forms of poor capacity of one type or another. Aid has played a key role in strengthening the capacity in the health and education sectors in many developing countries. Aid can also improve the production capacity or product quality in such a way that countries can benefit from new trade opportunities, and be used to strengthen infrastructure, the administration and the legal system so that the individual’s living conditions, administration of justice and respect for human rights and the framework conditions for investments in industry are improved. Additionally, aid can help to increase the developing countries’ own production of global public goods, for example by aid-financed purifying technology reducing CO2 emissions. Authorities that are really serious about developing their countries can in this way utilise aid to improve both the access to and production of global public goods. Whether using aid in this way is successful also depends on how it is given and the conditions that are set for it.

Governments in poor countries, however, are powerless when it is rich countries’ interests or policies that block their access to the public goods. Since Norway and other countries are part of a global system in which power and possibilities are systematically unevenly distributed, aid and good intentions are not the only things needed to make a positive contribution to development. Acknowledgement that conflicts of interest exist between rich and poor countries is required, as is a willingness to consider aspects other than Norwegian interests, and to give up privileges that rich countries currently have in a number of areas. Such changes can be painful to carry through in policy areas that apply to national interests that are regarded as vital and are therefore often difficult to achieve. Nevertheless, there is no excuse for not changing a policy that thwarts development in poor countries.

An attempt to establish a coherent Norwegian policy aimed at countries in the south must, both in relation to aid and other areas, seek to differentiate between different types of countries in order to avoid adopting a policy in which general solutions restrict the countries’ latitude to test and develop policies for economic growth that are adapted to national conditions.

The Policy Coherence Commission believes in general that rich countries must become more involved in creating as equal terms as possible for developing countries by ensuring that their policies in all relevant areas are conducive to promoting economic growth and development 2. As a minimum, they must ensure that their policies do not harm the developing countries’ battle against poverty. This is what the Commission has considered for Norway’s part and is the topic of this report.

The Commission takes for its basis that the analysis for such a coherent policy aimed at promoting development shall have a long-term perspective and focus on the political and economic framework conditions that countries in the south have to adopt a policy aimed at promoting development that can form the basis for reducing poverty. The aim here is not fighting poverty through increasing aid or loans to poor people or countries, but framework conditions that can make it easier for these countries to create long-term economic growth and reduce poverty themselves. It is important to make this distinction since the focus on the development policy is often on aid. Aid can be a crucial and necessary catalyst for contributing to development, but it is far from adequate as a tool to make this sustainable.

3.2 Poverty and inequality

Poverty is often described using statistics, as is also the case in this report. However, figures only tell half the story. Many of us have seen the figures before, read about poverty in the mass media and a few have even experienced it up close. However, only someone who has actually been poverty stricken can really understand what poverty entails, which rules out most of us. The poor themselves describe poverty as «always being hungry, always being tired, being denied our crystal clear rights, not being heard, no one speaking up for us, being overlooked, watching our children die of hunger and disease because we can’t afford enough foot or health services, not having enough money to give our children an education and being at the mercy of the weather and growth conditions.» 3 This describes a life that most people would not regard as dignified.

In 2004, around a billion people in low and middle income countries lived in extreme poverty. This equates to almost every fifth inhabitant in these countries 4. The extremely poor are those with less than USD 1 per day 5 to pay for food, housing, water, energy, health, education and other goods and services. The number that lives on less than USD 2 a day is double that. The majority of the world’s poorest do not live in the poorest countriesin the world. A number of middle-income countries with a growing middle class also have large groups of poor people. Around 75 per cent of the extremely poor live in the countryside and, according to estimates, the majority of them will remain there for a long time to come, despite the increasing urbanisation of poverty.

Figure 3.1 Employment is an important road out of poverty.

The poverty goal of 1 and 2 purchasing power-adjusted dollars a day is an attempt to describe income poverty, and forms the basis for the first Millennium Development Goal. Poverty, however, has many dimensions that are not intercepted through income, and other indicators can supplement the profile of the one-dollar-a-day target. The UNDP’s Human Development Index and Human Poverty Index, and the sub-indices these are made up of, are examples of such supplementary poverty indicators. The Gini coefficient is also a measurement of income distribution, and is necessary to see how poverty is spread and develops over time. These indicators do not, however, operate on a country level, and cannot provide definitive estimates of how many people are poor.

Figure 3.2 Geographic distribution of extreme poverty

Source GapMinder http://www.gapminder.org/fullscreen.php?file=GapminderMedia/GapTools/HDT05L/application.swf.

The calculations of the poverty development in various countries with the 1 and 2 dollar targets are debatable. The main problem is that they are often based on old or incomplete data. The calculation of the figures is based on comparisons of purchasing power in various countries. An extensive international collaboration programme (International Comparison of Prices) recently produced an update of these price comparisons, where the main aim was to compare the magnitude of the gross national product throughout the world. China and India took part in this work for the first time in a long time. One result of this was that the estimate of the magnitude of China’s gross national product fell by 40 per cent. India’s economy also turned out to be smaller than previously assumed. This also has consequences for the calculations of the number of poor. The World Bank has not yet completed its most recent analysis at the time of writing, but nevertheless estimates the number of poor in China to be around 3 – 7 percentage points higher than previously thought, which corresponds to approximately 35 – 85 million more poor. These new calculations therefore mean that the estimate of the level of poor can change. This does not imply, however, any change in the trend in poverty reductions in these countries.

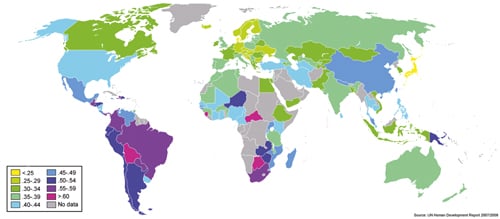

Figure 3.3 Map of global income inequality 2007 – 2008.

According to the World Bank, the number of extremely poor in the world fell by 260 million (10 percentage points) between 1990 and 2004 6. A great deal of uncertainty is linked to the estimates of the number of poor, but calculations from the bank indicate that the fall is due to the positive economic development in many Asian countries, and especially China 7. In East Asia, the rate of extreme poverty fell from 30 to less than 10 per cent from 1990 to 2004. Almost two thirds of those living in extreme poverty live in Asia, with only 30 per cent living in Africa. South of the Sahara, however, the share of those in extreme poverty is around 40 per cent, with this figure reaching as high as 60 per cent in some countries. In Africa, the living standard of the poor is generally much further below the poverty line than in other parts of the world, which means it will be considerably more difficult to take them up to a respectable income level.

Textbox 3.2 Living on one or two dollars a day in Malawi

The household survey from Malawi for 2004/2005 shows that the members of 57 per cent of the households had to manage on one dollar a day each. Members in 88 per cent of the households had two dollars a day to live on.

A household that spent one dollar a day per member spent around 68 cents of each dollar on food (nothing on alcohol or tobacco), 6 cents on clothing and shoes, 16 cents on housing, 6 cents on health and 4 cents on sundries.

A household that spent two dollars a day per member spent around 1.29 cents on food, 5 cents on alcohol and tobacco, 4 cents on clothing and shoes, 47 cents on housing, 5 cents on health and 10 cents on sundries.

According to calculations by the World Bank, Malawians need 58 cents to cover their minimum calory requirement of 2,100 calories. However, this is only the minimum requirement in life or death situations. A healthy and balanced diet that can ensure children reach their physical and mental growth potential requires much more. This is particularly the case for pregnant women and children below two years of age. Access to nutritional food is therefore vital for mother and child in order to avoid damage caused by a lack of nutrition, which is impossible to rectify afterwards.

The 1-dollar a day households can afford a bit more than the minimum calory requirement, but barely enough to protect their children from malnutrition. The situation is all the more serious because more than half of all Malawian households consume less than the average household in the example.

The 2-dollar households and those earning more, can afford enough nutritional food for all household members. However, this is only slightly more than 12 per cent of all households. In a village economy such as that in Malawi, it only takes one poor harvest for incomes for a large number of these households to fall below the minimum.

The reasons why around a billion people live below the poverty line are many and complex. However, they all face a daily struggle to obtain food, shelter, medicines and education for their children.

Figure 3.2 shows how the strong economic growth in Asia has affected the global distribution of extreme poverty. If this development continues at the present rate, two thirds of the poorest will live in Africa by 2015. Viewed in isolation, the share of poor in Africa has for a long time stood at around 45 per cent, but fell to 41 per cent from 2002 to 2004. The development in Asia shows that there may be hope for Africa to also gradually reverse the trend and escape from poverty.

Distribution is a deciding factor in the reduction of poverty through economic growth. There is increasing evidence to suggest that the growth’s contribution to reducing poverty is considerably lower when inequality in society is growing than when becoming less 8. The development in inequality is also an important reflection of the prerequisites for combating poverty. According to the UNDP, growth strategies that also place the emphasis on reducing inequality will lead to less poverty, both in absolute and relative terms.

An analysis of the information in the World Income Inequality Database (WIID) shows that inequality within countries fell in the 1950s and 70s in most industrialised and developing countries. However, since the 1980s, this development has stagnated or been reversed. The data from the last two decades shows a significant increase in inequality for a number of countries. At the start of the 1980s, 29 of the 73 countries with sufficient figures in the database had a Gini coefficient of more than 0.35 – 0.40. At the end of the 90s, the number of countries with such a high level of inequality increased to 48. This trend is evident in rich countries as well as poor countries.

Researchers at the University of Oslo have estimated how much redistribution is required to elevate the population in a developing country to above the poverty level of two dollars a day (Lind and Moene 2007) 9. The lower such a potential tax rate is, the more miserly the country appears. The researchers have found a dramatic increase in global miserliness in the past 30 years. South Africa is the world’s most miserly nation, since an income tax of 1.07 per cent of the income from those that are not classified as poor would be sufficient to take the country’s entire population above the poverty level. Other miserly countries include Namibia and several countries in South America. All of these countries have relatively large supplies of resources to combat poverty, but little is done. For example, very limited amounts are invested in education and health. At the other end of the scale, we have countries such as Malawi, Tanzania and Mozambique, with an income level that is so low and a poverty level that is so high that not even totally even income distribution would eradicate the poverty. Reducing poverty in countries such as these requires continued high economic growth. The researchers found no correlation between a country’s miserliness and economic growth.

3.3 The significance of aid

As a catalyst for initiating key social functions, aid can help to reduce poverty in the short and long term, but aid alone will never be able to solve the world’s poverty problems. Research shows that aid is most effective when aimed at the poorest countries with authorities that adopt an active and effective policy for combating poverty 10. However, it cannot be concluded that aid should mainly go to countries with effective governance. Based on fairness, channels also need to be found to help the poor in countries with weak governance and deficient democracy.

Although Norway is a substantial contributor internationally, no more than 37 per cent of Norwegian bilateral and multilateral aid went to the least developed countries in 2005 11. Table 3.1 shows that five of the ten largest recipients of bilateral Norwegian aid in 2007 are not classified in the group with low human development by the UN. The table also shows how Norway’s wish to play a role in connection with peace processes and conflict-solving characterises the priorities for the aid (Sudan, the Palestinian areas and Afghanistan). Furthermore, three out of the four largest recipients of aid are countries with extremely weak governance. Poor governance such as corruption, political instability and internal unrest constitute a barrier to combating poverty.

Table 3.1 Indicators for the 10 largest recipients of Norwegian bilateral aid in 2007

| Norwegian aid (NOK mill.) | Human development (1=highest, 177=lowest) | Extreme income poverty (% below 1 $ per day) | Income poor (% below 2 $ per day) | Governance (1=best 212=weakest) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sudan | 701 | 147 (medium) | ..1 | ..1 | 193 |

| Tanzania | 670 | 159 (low) | 57.8 | 89.9 | 123 |

| Palestine | 622 | 106 (medium) | ..1 | ..1 | 176 |

| Afghanistan | 553 | ..1 (low) | ..1 | ..1 | 201 |

| Peru | 553 | 87 (medium) | 10.5 | 30.6 | ..1 |

| Mozambique | 412 | 172 (low) | 36.2 | 74.1 | 120 |

| Philippines | 463 | 90 (medium) | 14.8 | 43.0 | ..1 |

| Zambia | 436 | 165 (low) | 63.8 | 87.2 | 138 |

| Uganda | 409 | 154 (medium) | ..1 | ..1 | 143 |

| Malawi | 321 | 164 (low) | 20.8 | 62.9 | 139 |

1 Data not available.

Source Norwegian aid: Norad; Human development: Human Development Index from Human Development Report (HDR) 2007/08; Income poverty HDR 2007/08; Weak governance: World Governance Indicators 2007 (World Bank). The figure in the tables refers to the country’s average ranking of 6 indicators.

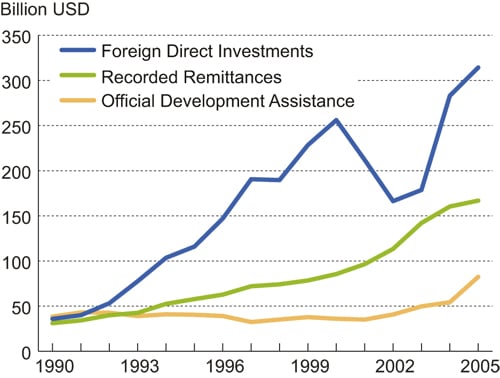

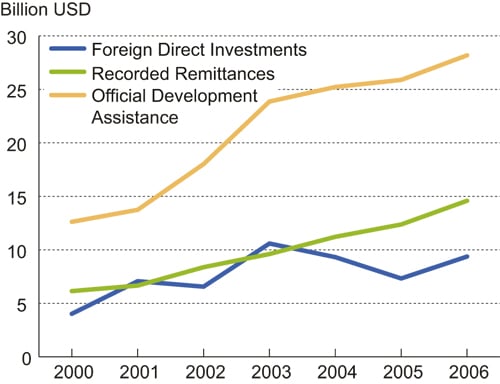

The significance of aid for the economies in developing countries varies according to level of development and the magnitude of the economies in the countries. Figure 3.4 shows how foreign investments and migrants’ remittances from abroad add up to more than aid to all developing countries. Aid, however, is still an important source of financing for the least developed countries. Figure 3.5 shows that transfers from migrants and direct foreign investments combined account for slightly less than the official development aid to the least developed countries.

Figure 3.4 Financial flows to developing countries. 1990 – 2005. USD billion

Source World Bank, UNCTAD and OECD.

Figure 3.5 Financial flows to the least developed countries. 2000 – 2006. USD billion

Source World Bank, UNCTAD and OECD.

Relatively large amounts of Norway’s bilateral aid are aimed at Africa – almost NOK 5 billion in 2006. This is a total of 40 per cent of the Norwegian bilateral aid. Beyond aid, Africa has little significance in the Norwegian economy: imports from Africa account for approximately 1 per cent of total imports to Norway. The value of total import from Africa is somewhat greater than the aid, with NOK 6.6 and 5.3 billion respectively. Correspondingly, only a small fraction of Norway’s direct investments in operations in other countries goes to Africa, but the amount is nevertheless far higher than the aid. The Norwegian investments in Africa are almost exclusively within oil production, and are dominated by StatoilHydro. This illustrates how marginal the scope of the aid is in relation to other resource flows to developing countries. World aid accounts for a fifth of a percent of the world’s GDP.

Aid is not a main topic in this report. A number of processes are currently focused on how the aid contributes to development and combating poverty. The main process is the monitoring and evaluation of the implementation of the Paris declaration on effective aid, which deals with how the donors coordinate their programmes between themselves and how they adapt the programmes to the recipient countries’ needs and plans. Other processes look at how aid can be used to counteract corruption and not result in more corruption. Further processes seek to get the donors to increase their aid in line with promises made by the G8 and at various summits. Aid, however, is discussed where relevant.

3.4 Coherent policies for development in an international perspective

The acknowledgement that a number of other policy areas have a greater significance for the fight against poverty in developing countries than the aid policy, formed the basis for the UN member countries at the start of the new millennium endorsing Millennium Development Goals 7 and 8 on national responsibility for global, sustainable development and global partnership for development. Goal number 8 emphasises the development of transparent, rule-based, predictable and non-discriminating international trade and finance systems, debt relief and increased aid to countries that adopt binding policies on reducing poverty. Securing access for developing countries to relevant technology, particularly within medicine and information and communication technology is also covered. Goal number 7 focuses on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The fact that all UN member countries supported these goals confirms the extent of agreement that rich countries have a special responsibility to change their own policies as well as the policies of international organisations aimed at combating poverty. However, there are major differences regarding how countries and organisations follow up these goals and the ideal for a coherent policy on development.

Policy Coherence for Development has been a core area for OECD/DAC for a number of decades. OECD also has the following definition of Policy Coherence for Development:

Policy Coherence for Development (PCD) means working to ensure that the objectives and results of a Government’s development policies are not undermined by other policies of that Government, which impact on developing countries, and that these other policies support development objectives, where feasible.

The definition implies that national authorities should also identify and utilise any synergies between the development policy and other policy areas. OECD has identified agriculture, trade, investments, knowledge and technology exchanges, including medical research, migration, the environment, security and arms trading as the areas in which the OECD countries’ policies can potentially have the greatest significance for combating poverty in the developing countries 12. In this report, the Policy Coherence Commission relies on the OECD’s definition and also covers most of the topics that the OECD identifies as key areas.

Textbox 3.3 Coherent policy for development viewed from the global south

«The policy coherence argument tries to advocate for taking into consideration the interests of developing countries in policy-making. However, as many critiques have noted, coherence has always been and will continue to be a function of competing and conflicting interests and values. Unless donor countries become more ethical and realise that they cannot continue building their progress on the retrogression of other countries, policy coherence will take long to become a reality.»

Pamela K Mbabazi

Dean, Faculty of Development Studies, MbararaUniversity, Uganda

«I would say that there are really two sources of incoherence in the developed industrialised countries’ attempts to address issues of development and poverty in the countries of the South.

Incoherence arising out of conceptual (mis)understanding of development; and

Incoherence arising out of practice at variance with stated «development» policy objectives and means to development set out by OECD countries.»

Yash Tandon,

Executive Director, The South Centre

In 2003, Sweden was the first country in the world to pass a law for a policy on how, within all policy areas, to work towards a common goal for global development, i.e. with a focus on both global public goods in general and on a coherent policy for development. Annual reports on this are submitted to the Swedish parliament 13. In Sweden, as well as combating poverty, global development also includes the improvement of human rights and democracy, as well as environmental sustainability and equality. Particular emphasis is placed on developing a coherent environmental, trade, agricultural, immigration and security policy in Sweden. Sweden has gained distinction as a leading force in attempts to reduce sugar production in the EU, in order to enable developing countries to secure a stronger market position 14.

The authorities in the Netherlands, Finland and the UKare also working systematically to develop a more coherent policy for development. The Netherlands prioritises the policy areas of agriculture, trade, intellectual property rights and public health, product standards, fishery, the climate and energy, migration, as well as peace and security. Among other things, the Netherlands has endeavoured to reduce the EU’s subsidising of cotton production because this contributes to low world market prices for a key export product from developing countries 15. The UK Government has attached importance to trade, migration, research/technology, the international financial institutions, British foreign investments and environmental and security policies 16. In 2006, the British parliament passed a law that requires the cabinet minister for international development to report to them annually on how other departments’ policies obstruct or facilitate the reduction of poverty and development.

EU member countries undertook in 2005 to ensure that the EU policy in its entirety contributes to achieving development policy goals. In addition to aid, the EU has also identified 11 policy areas with special significance for the developing countries: trade, the environment, security, agriculture, fishery, working conditions, migration, research and innovation, the information society, transport and energy 17. However, a study has shown that the EU is faced with a major challenge since its processes for case preparation mean that various policy areas are partly handled in isolation from each other. There is therefore an extra challenge for the EU bodies to establish systems that facilitate the fulfilment of the obligations for achieving a coherent policy for development 18.

In Norway in 2004, the Government launched a number of initiatives for strengthening policy coherence for development in its White Paper no. 35 (2003 – 2004) «Fighting poverty together». The report has a separate chapter on partnerships for development, which draws attention to the following policy areas: trade, investment, debt relief, migration, the environment, knowledge and technology exchange, combating corruption and money laundering, a decision-making role in international fora and financing of aid and global public goods. Norway has made progress in some of these areas, but as this report outlines, is lagging behind in other areas. However, Norway has made a considerable effort within global health and can also take credit for launching a major international campaign to save rain forests and to follow this up with a substantial multi-annual grant.

3.5 Division of power and influence

Norwegian policies that affect development in poor countries and the potential for more coherent policies are affected by the international division of power and states’, organisations’ and individuals’ willingness and ability to affect and change this in favour of the poor.

The competition for natural resources, forming alliances, military influence, economic development and the tug-of-war between political and religious ideas affects the combat against poverty. The USA is still the dominating superpower, but Europe has become more coordinated through the European Union. Simultaneous to this, growing economies, such as China, Russia, Brazil and India are showing their desire for greater international influence. Hitherto, the least developed countries and the poorest populations have had very limited power and influence, including in the UN and other international organisations.

A number of Asian countries that have achieved high economic growth and made good progress in the fight against poverty have substantial challenges regarding human rights and the deterioration of the climate. The magnitude of the emissions from energy production and the manufacturing sector in these countries make initiating a binding dialogue with them on emission reductions a main challenge. The limited effort in many western countries to curb climate change coupled with Asian countries’ desire to grow quickly, which leads to a major need for resources, is however a barrier.

How this will eventually manifest itself in global power politics is unclear. The dynamic in the development in Asia has been seen in the increased competition for resources – e.g. in Africa, where China in particular is active. All of the so-called BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) have experienced substantial economic growth in recent years. In time this economic power may translate into political power, with an accompanying shift of power from west to east/south. The fact that China offers developing countries in Africa economic trade that is not tied up with political conditions is an important premise for the further development of the global economic system in which developing countries have to operate. If the international community is to succeed in creating a common development strategy, these new weighty players must also be included in the dialogue on framework conditions for aid and development policies.

The BRICS countries have all played a key role in the ongoing Doha round in the WTO through leadership by facing the developing countries’ requirements for policy space and greater market access. The term «policy space» has been defined by the UNCTAD as «room for potential within domestic politics, particularly in the fields of trade, investment and business development within international rules, obligations and global market considerations». This bears the message that the BRICS countries will play a more prominent role in key political fora in the future. It is interesting to note that a number of leading countries, e.g. the UK, are taking on board that the BRICS countries should have a larger role in central international organisations such as the UN, WTO, IMF and the World Bank. IMF’s director has also stated that a redistribution of rights and obligations that reflect the current economic dimensions is necessary in order to protect the legitimacy of the IMF. Various intersecting interests among developing countries make it important, however, to ensure that the changes in the global economic and political power structures also contribute to policies that are more coherent with the poorest countries’ development goals.

Governments, however, do not have a monopoly on power and influence, with non-government players gradually having gained more power in international politics. These often contribute funding, expertise and a capacity for mobilisation, which are absolutely vital to establishing bodies for global governance. The human rights movement, trade union movement and the green/environment movement are examples of such critical networks in international politics. Also included in this group are large foundations that finance various causes in developing countries, such as the Gates Foundation, and labour organisations. Combined analysis and pressure groups, such as the International Crisis Group, are also key players.

Multinational companies are also playing an increasingly greater role. This often has a major effect on the national economies in which they operate and, by virtue of their size and scope, also have considerable influence globally. The three largest companies in the world, Wal-Mart, Exxon Mobil and Royal Dutch Shell had a total turnover of USD 1,017 billion in 2006. This surpasses the gross national product for the whole of Africa south of the Sahara (which was USD 713 billion). The largest company in terms of turnover, Wal-Mart, has a turnover of USD 351 billion which is almost as high as all of the least developed countries put together (USD 367 billion). Human rights and climate considerations need to be protected through the companies’ own rules for social responsibility and through the national and international framework conditions for industry in the countries in which they operate. The latter is also of great significance for the distribution of the growth that the companies help to create.

This increased diversity and the changes in power and influence challenge the existing global model of Government. It has also led to the formation of fora such as the World Economic Forum in Davos, where new players and representatives for national states and global organisations meet to discuss key global issues and subsequently draw on them in the UN, OECD and in board discussions in the international financial institutions. The process has also shown bodies such as the OECD/DAC that they need to identify new ways of working in order to take account of players with a major influence on their work.

3.6 Measuring a coherent policy for development

Measuring how coherent the overall politics in a country are with regard to facilitating development is extremely difficult. In practice, such assessments would need to be based on recognised causal relations. This would be relatively non-controversial in some areas, particularly where there is general agreement within research on which type of policies actually help to reduce poverty. In areas where there are widely differing opinions among researchers as to what the causal links are conclusions would be difficult to draw. It will therefore be difficult in many areas to draw definitive conclusions in the assessment of the coherence for development of Norwegian policies.

In some countries Governments have made statutory provisions for the reporting of coherence. In the EU, the reporting of the Millennium Development Goals must include an assessment on development related coherence. In 2007, the EU Commission published a self-evaluation of the policy coherence for development in the EU’s and the member countries’ policies 19. The development authorities in Sweden and the UK report annually to the national assembly on the coherence within the entire scope of the Government’s policies. Such reporting also takes place in the Netherlands. In Norway, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ reporting on Millennium Development Goal number 8 in 2004 20 has so far been a one off.

It is unlikely that a national authority’s self-evaluation can provide a critical and explicit assessment of policies. It is more likely to expect it to be characterised by initiatives that can have a positive bearing on the developing countries, with negative development characteristics in their policy being undercommunicated.

External evaluations are therefore important. An example of such an evaluation is the EU coherence project, which is financed by the Dutch Government and some voluntary organisations in the Netherlands. They carry out regular analyses of the coherence between selected areas of the EU’s policies, such as agriculture (sugar and cotton), fisheries (the EU fleet’s haul in developing countries’ waters), health (patents on medicines and trade) and arms trading, 21 and are a key premise provider both in the national debate and within the EU.

The most well-known attempt at creating an overall measurement of how rich countries’ policies affect the poor in developing countries, is the Commitment to Development Index (CDI). The index is made up of measurements of the policy within six areas with a major bearing on the reduction of poverty: aid, trade, investment, migration, environment, security and technology 22. In 2007, Norway was ranked third out of 21 rich countries, after the Netherlands and Denmark. Norway had the highest score of all countries with regard to security policy and the environment. Norway’s major contribution of personnel and funding to international peace-keeping and humanitarian interventions has earned us a high number of points, as has the low emission of greenhouse gas per capita (emissions from petroleum recovery on the Norwegian continental shelf are not included) and the reductions we achieved between 1995 and 2005. Norway is in fourth place with regard to aid due to large allocations in relation to the country’s revenues, and is sixth within investment policy due to measures to support Norwegian investments in developing countries. Norway scores above average on technology, and average on migration. Norway scores second lowest out of the 21 countries on trade due to the considerable trade barriers (duties and subsidies) on agricultural products.

The CDI’s methodology for considering whether the policy is coherent is the subject of much debate. Data, criteria and the measuring methods are all debatable, e.g. there is no consideration given to the fact that around 25 per cent of imports to Norway are exempt from duty. There is also political disagreement on some of the assessments that lie behind the index, e.g. the ranking with regard to contributions to global security. The index and its 6 sub-indices, however, provide an interesting profile of changes in the OECD countries’ policies over time.

In Norway, The organisation «The future in our hands» has developed a type of measurement for coherence through calculating the indicator «the i-help», i meaning industrialised country, where an attempt is made to quantify the benefits Norway has from the economic imbalance between rich and poor countries. This is then put up against the aid Norway gives to poor countries. According to The Future in our hands, Norway received NOK 28 billion from developing countries in 2005, which is 62 per cent more than the amount given in aid to developing countries that year. This is based on industrialised countries’ advantage in the commodity, capital and labour markets, combined with the costs to developing countries of damage to the environment caused by industrialised countries 23. The i-help, however, only calculates Norway’s gains, and not the corresponding loss for the developing countries, which could be considerable in a poverty perspective.

The OECD’s checklist for coherence from 2000 is a tool for policy development in the member countries. It lists policy areas that should be considered in relation to coherence 24. The OECD has also carried out an evaluation of the coherence between the policies in the member countries 25. With regard to Norway, the study is based on the evaluation (Peer Review) of Norwegian development policy from 1999. At that time the OECD believed there was a relatively strong awareness in Norway of the need to develop a coherent policy aimed at the developing countries. It was particularly noted that Norway had a GSP system that provided favourable market access for selected developing countries, that Norway actively promoted the interests of its main partner countries in international discussions on trade, development and global public goods and that Norwegian aid was to a large extent not tied to the purchase of Norwegian goods and services. The OECD recommended, however, better access to and transparency in relation to policies that are potentially not coherent, particularly within the agriculture sector, in order to enable a more effective evaluation of differences and adaptation costs. The OECD also had a recommendation for the organisation internally in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and between the ministries to ensure a more coherent policy for development. The OECD’s Peer Review of Norwegian development policy from 2004 placed a positive focus on coherence being an explicit aim of this policy, but advocated a stronger foundation for coherence throughout the entire Government.

One of the evaluation areas 26 of an external evaluation of the Norwegian policy on sustainable development was the relationship between trade and aid. The evaluation concluded that the Norwegian policy is not very coherent; it was generous with aid but restrictive in the trade policy. According to the evaluation, this can particularly affect poor countries, except the least developed countries, which have duty-free and quota-free status for export to Norway. The evaluation panel recommended a clarification be made of the consequences for Norwegian districts and Norwegian consumers of introducing a more liberal trade policy within agriculture and textiles, and to improve official indicators for both trade and aid.

One objection to the existing evaluations of policies in relation to coherence is that they do not properly document the effect that the evaluated policy has in developing countries. Neither do they take into account that developing countries are different and have different interests, and that the effect of the policy will therefore vary from country to country. Thus, there is a need for greater knowledge on how Norway’s and other rich countries’ policies affect developing countries.

3.7 Consequences of how the policy is formulated and recommendations

The Norwegian authorities have a duty to help fight poverty in developing countries. Although Norway is a small country, Norwegian policies have an effect on the developing countries through both national policies and participation in international processes and organisations. The fact that the political willingness or ability in a number of developing countries hinders the reduction of poverty, is not permissible as a general argument against giving these countries resources or removing obstacles in the fight against poverty that the developing countries run into.

The Policy Coherence Commission’s mandate is based on a goal to minimisethe negative effects of Norwegian policies on developing countries, and strengthenthe positive effects. The mandate thereby places a great deal of emphasis on identifying and initiating measures within the areas where Norwegian policies contribute to the undermining of the fight against poverty. Minimisingthe negative effects – as opposed to reducingthem – entails taking as much consideration of the interests of developing countries as possible without harming vital Norwegian interests where these are in direct opposition to each other. In order to fulfil such a wish, Norwegian policies need to be modified within a number of areas. Strengtheningthe positive effects is interpreted as follows: where Norwegian interests coincide with the interests in poor developing countries such synergies shall be utilised. In these cases, the focus will be on strengthening individual elements of existing policies. In some cases, this may entail a win-win situation, but increased focus can also affect other measures due to limited resources.

Figure 3.6 Producing flowers for sale in Europe has become an important source of income for many countries in Africa.

This report contains a number of proposals for measures to increase the effect on the reduction of poverty and scope for economic and social development within Norwegian policies in areas that we believe to be crucial to improving the framework conditions for development.

Poor populations in developing countries have very limited opportunities to exercise influence. When political decisions are taken in Norway, Norwegian interest groups are first in line. It is a political choice whether and when the interests of the poor are given priority ahead of Norwegian interests. However, it is difficult to legitimise the population and authorities of Norway not having or obtaining knowledge on the consequences for the poor in developing countries of the decisions that are taken. In order to make the authorities responsible, they must regularly document and publish the consequences of decisions made in Norway on the poor in developing countries. The authorities must also consider this knowledge when making decisions. Developing a more coherent policy for development is not a one-off event that an official Commission can carry out. It requires a continuous and systematic effort by the authorities, and the work must be institutionalised. This report includes proposals on how these can be achieved.

The Policy Coherence Commission believes that Norwegian policies are nowadays formulated through decision-making structures that are not sufficiently adapted to situations in which the mutual dependency that stretches across country borders affects almost all policy areas. This is problematic in cases where Norwegian political decisions are harmful to or obstruct the developing countries’ possibilities for fighting poverty. However, the Commission also believes that problems can arise if the absence of effective institutional mechanisms for increased coherence deprives us of opportunities to create positive synergies between the national policy-making and Norway’s foreign and development policy objectives.

For example, the Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion has responsibility for the immigration and integration policy. A key tool for a coherent policy for development in the area of migration and remittances is therefore outside the scope of responsibility of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and points towards a need for extensive coordination across the various ministries. The Ministry of Agriculture and Food has ministerial responsibility for the agriculture policy and the Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs is responsible for the fisheries policy, while the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is responsible for the actual negotiation process in the WTO. The Ministry of Finance is responsible for Norwegian policy with regard to IMF; a responsibility that is delegated to Norges Bank – the Central Bank of Norway. IMF’s key role as financial adviser and donor to poor countries entails challenges for the Government when trying to establish a primary policy that is capable of and takes consideration of each ministry’s (including the Ministry of Finance) distinctive perspectives and interests. The Ministry of Finance is also responsible for the Government Pension Fund – Global, which develops and administers economic policy guidelines in relation to investments in developing countries. The Fund has shares to a value of NOK 4.8 billion in companies that the Rainforest Foundation Norway claims damages the rain forest in a number of poor countries, 27 while the Government has established a fund that can spend up to NOK 3 billion per year for five years on saving the rain forest. The tension between Norwegian investments abroad and the effect of these on the environment, and the basis of existence for poor countries is only one example of the bureaucratic and political challenge faced in the coordination efforts between the ministries.

These examples of how different ministries are involved in cases relevant to a coherence in development relevant policies indicate that there is a need for new institutional and political mechanisms in order to ensure coherence. The fact cannot be ignored, for instance, that there are varying interests and elements of territory struggles between the ministries, which partly stems from political tensions, but which can also have bureaucratic origins. This is expressed in various ways, but the core is that there is immense power in Government’s control of information, interfaces with key partners abroad and not least budgets. Power is particularly prevalent in the Government’s knowledge and expertise within various specialist fields. The Commission notes that knowledge from the global south and competent environments other than the World Bank should be involved in order to create a broad knowledge base. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is in a special position in this regard, with an assumed leading expertise in diplomatic processes and the primary relationship with other countries. In line with all specialist fields being globalised and «national» political fields gaining a stronger international dimension, however, the various other ministries are also becoming more key players in international fora, often by virtue of extensive specialist expertise, which the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with its broad scope of responsibility cannot be expected to possess. Additionally, the Office of the Prime Minister by virtue of its own international department has gained a more prominent role in Norwegian foreign politics. This changes the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ historical role as a gatekeeper and interface to the outside world.

The fact that many requirements are placed on the coordination between the ministries as a result of an internationalisation of specialist fields is in addition to any political tensions between such political fields with regard to their effect on developing countries. Global changes thereby create pressure to develop more effective coordination and interconnection mechanisms across ministries, not just on the civil service side but also politically. In the USA, the tradition has been to place the responsibility for interconnecting different parts of the security policy in the position of national security adviser. The Netherlands have a separate unit in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that monitors policy areas of major importance to policy coherence for development both nationally and in the EU. Issues that represent challenges in this field are studied and presented to the Government by the departmental director as part of the decision basis. In Sweden, the Development policy department within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is organised according to the main lines in the Swedish policy for global development and has a separate unit for policy coherence for development and policy development. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs must by law report annually to parliament on its own and other ministries’ contributions to realising the policy for global development.

However, it is not enough just to coordinate the policy across the ministries. Political authorities must also act in accordance with and work with a relatively large number of non-government players. The input value for a specialist field today is that all implied playersmust be identified and dealt with, including Governments, in order to then initiate institutionalised cooperation with as many players as possible. Greater coherence, and administrative handling aimed at strengthening the coherence in relation to developing countries can take inspiration from existing forms of collaboration between the Government and non-government players. That which is often referred to as the Norwegian model, with close – too tight according to some – ties between the Government and representatives of the civilian community and industry can form the basis for establishing better coordination mechanisms between various ministries and between the Government and other players. Trust and transparency are key concepts here. As a small country with a stable political system, an effective bureaucracy and relatively high degree of support for the goal of fighting poverty, Norway is in a better position than many other countries to establish political and organisational mechanisms for a more coherent policy for development. This should not be interpreted as if no conflicts or differences of opinion exist here. Nevertheless, in an administrative and political sense, Norway is in a good position to be able to develop new mechanisms for creating debate, ensuring an overview and supervision, and coordinating a more coherent Norwegian policy aimed at countries in the global south.

Commission member Kristian Norheim believes that aid should have been included as a main topic in the Commission’s work and report, and in relation to the coherence issue. Any analysis of coherence for development in Norwegian policies will be lacking where it has been decided to exclude an evaluation of what role the Norwegian aid effort plays and not least a critical assessment of whether the aid policy actually builds on the goals for a global reduction of poverty and better framework conditions for economic growth and development in the poorest countries. Aid is one of many tools in the development policy, and in Norway one of the most important. It is Kristian Norheim’s clear view that the report by the Policy Coherence Commission will remain inadequate as long as aid is excluded in a broad sense from the work of the Commission. Where it is the case that aid can not only produce good results, but also lead to poor results, and even worse to a deterioration of the conditions for growth and development in the poorest countries, an analysis of these conditions should be included as a natural part of a Norwegian coherence policy aimed at the poor countries. Good intentions can give poor results, and where certain parts of the traditional aid policy contribute to the undermining of the effort in the developing countries in relation to fighting corruption and the necessary economic and political reforms, this must be viewed in context in order to be able to make Norwegian development policy more coherent.

The Commission recommends that the Government considers institutional reforms that can strengthen the political and administrative capacity to develop a more coherent policy for development.

The Commission recommends that the Government strengthens the reporting to the Storting, both with regard to results and ambitions for a more coherent policy for development.

The ambitions for a more coherent policy for development should be expressed through the Government’s long-term programme, preferably with a separate chapter being dedicated to presenting the Government’s most important priorities in this area for the coming parliamentary session.

Correspondingly, Norway should follow the example of the UK and other European countries and introduce regular reporting to the Storting on the overall effects and results of Norwegian policy in relation to the development policy goals. Reports should be submitted at least once per parliamentary session.

Weighty decision-making processes are, to an increasing extent, involving more ministries. At a political level, this is handled through the Government collegiate, while at civil service level it is the content of issues that determine on a case by case basis where the administrative responsibility lies. The Commission understands the benefits of the ministry that is closest to the issue having the main responsibility for preparing the issues for political processing. Nevertheless, the Commission believes that there is a need to develop collective administrative expertise with resources and a mandate to protect the needs for a more coherent foreign and development policy, based on the policy in all relevant ministries. A resource of this type should be developed and given a mandate in order to ensure better coordination of political decisions with a special bearing on increased coherence.

The Commission recommends that the Government strengthens the civil service’s capacity for a collective preparation of political decisions across the traditional borders of the ministries. As is the case in Sweden and the Netherlands, Norway should establish a unit in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which is given the task of both monitoring relevant policy areas and coordinating the work aimed at a coherent policy for development.

The Commission recommends that the Government enables greater knowledge in this field through a more systematic evaluation and analysis of the collective Norwegian presence in developing countries. The Policy Coherence Commission believes it is important that a contribution is made to both developing and exploiting different research environments in developing countries.

A regular and independent evaluation of a coherent policy for development should be ensured at a superior level. This should be commissioned to various research centres, including in developing countries.

The Commission believes there is a need for greater knowledge on how the collective Norwegian presence affects developing countries’ ability and willingness to reduce poverty and encourage development. The Commission therefore recommends that concrete case studies are carried out in selected countries on the effect of all aspects of Norwegian policies. The Commission is of the opinion that it will be beneficial if strong expert environments in the global south help to develop such studies.

A board or liaison Commission should be appointed consisting of representatives from industry, the trade union movement, research and the civil community, among others, in order to ensure a broad basis for a debate on a coherent policy for development.

Footnotes

GLOBAL PUBLIC GOODS: International Cooperation in the 21st Century, edited by Inge Kaul, Isabelle Grunberg, and Marc A. Stern. Copyright© 1999 by Oxford University Press

A coherent policy can in principle take its starting point from any policy. Most Governments have a body that ensures the greatest possible degree of coherence in general. A few Governments have also noted that weak, poor countries’ interests viewed in relation to strong, rich countries’ interests requires that special attention is given to coherence in policies on the terms of development and poverty reduction through regulations, institutions or in other ways.

Voices of the Poor, World Bank 2000

World Bank, World Development Indicators 2007. The World Bank og Oxford University Press http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/ Resources/WDI07section1-intro.pdf

Purchasing power-adjusted

World Bank: World Development Indicators 2007. The World Bank og Oxford University Press http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/ WDI07section1-intro.pdf

Calculations from the International Comparison Programme in 2007 show that the purchasing power in the Chinese economy has been overestimated. Upward adjusted living expenses will be used as a basis for new measurements of poverty, which will no doubt increase the estimates of the number of poor in China.

UNDP (2005): Energizing the Millennium Development Goals: A Guide to Energy"s Role in Reducing Poverty. UNDP/BDP Energy and Environment Group http://www.energyandenvironment.undp.org/ undp/indexAction.cfm?module=Library&action=Get-File&DocumentAttachmentID=1405

Lind and Moene 2007.

Annual Report 2007: Norwegian Bilateral Development Cooperation. Norad May 2008

UN, Human Development Report 2007/2008 statistics http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/data/

ECD: The DAC Guidelines. Poverty Reduction 2001. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/47/14/2672735.pdf og OECD, Policy coherence: Vital for global development. Policy brief, July 2003. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/ 1/50/8879954.pdf.

Swedish Government: Sweden’s policy for global development. Regeringens proposition 2002/03:122 http://www.regeringen.se/content/1/c4/07/73/ 874fe3e0.pdf. More information on Sweden’s coherence policy to be found at http://www.regeringen.se/sb/d/ 2355;jsessionid=a0tAimr_6Bma

Sweden’s policy for global development. Regeringens skrivelse 2005/06:204 http://www.regeringen.se/content/1/ c6/06/44/04/420a32ec.pdf

Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2006): Policy coherence for development. Progress Report. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Hague June 2006. See also http://www.minbuza.nl/en/developmentcooperation/ Themes/poverty,coherence/policy_coherence_for_development.html

DFID Annual Report 2007: Development on the Record. Department for International Development. http://www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/departmental-report/ 2007/

EU Commission: Communication from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament and the European Economic and Social Committee of 12 April 2005 - Policy Coherence for Development – Accelerating progress towards attaining the Millennium Development Goals (COM(2005) 134) http://europa.eu/scadplus/leg/en/lvb/r12534.htm

van Schaik, Louise, Michael Kaeding, Alan Hudson, Jorge Núñez Ferrer, Christian Egenhofer (2006): Policy Coherence for Development in the EU Council: Strategies for the Way Forward. Centre For European Policy Studies Brussels shop.ceps.be/downfree.php?item_id=1356.

EU Report on Policy Coherence for Development. European Commission, DE 139, November 2007 (Commission Working Paper COM(2007) 545 final og Commission Staff Working Paper SEC(2007) 1202). http://ec.europa.eu/development/icenter/repository/ Publication_Coherence_DEF_en.pdf.

Global Partnerships for Development. Millennium Development Goal No 8. Progress Report by Norway 2004, http://www.regjeringen.no/upload/kilde/ud/rap/2004/ 0217/ddd/pdfv/225797-mdg8-rapport.pdf

www.eucoherence.org

Center for Global Development 2007. http://www.cgdev.org/section/initiatives/_active/cdi/

The Future in our hands: I-hjelpen 2006. Om de fattiges bistand til de rike. Rapport 4/2006. Framtiden i våre hender http://www.framtiden.no/filer/R200604_Ihjelpen_2006.pdf

OECD (2001): The DAC Guidelines. Poverty Reduction. OECD http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/47/14/2672735.pdf

OECD (2004): Extracts From The Development Co-Operation Review Series Concerning Policy Coherence http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/23/16/25497010.pdf

Danielson, Anders, Conny Hägg, Helene Lindahl, Lars Lundberg, Joakim Sonnegård and Joseph Enyimu (2007): A peer review of Norway’s policy for sustainable development. *link in English: http://www.regjeringen.no/ nb/dep/fin/tema/Barekraftig_utvikling/Sammendrag-fra-peer-review-av-barekrafti.html?id=458363

http://www.regnskog.no/html/562.htm