9 Migration policy

9.1 Migration and the effect on poverty

The reasons for people relocating over country borders are many and complex. It could be due to necessity as a result of escaping war, persecution and disasters. It can also be because there is a desire to find work or get an education. A large number of relocations are family related. Many seek to reunite with family members that have already left to find work or take up education, or who have fled. There are also those who marry abroad and seek to immigrate.

Figure 9.1 Increasing numbers are moving from one country to another.

The number of international migrants has doubled since 1980. Today there are almost 200 million migrants internationally 1. However, migrants only make up a small percentage (3 per cent) of the world population. In the developed world, the share of migrants in the population, according to the OECD, is three times higher. Figures from the World Bank show that migration from south to north constitutes more than a third of all international migration. A quarter of all migration takes place between developing countries, while relocation between developed countries accounts for 16 per cent. With regard to the inhabitants of the world’s poorest countries, migration represents a sought after, but limited opportunity to escape poverty, since people from these countries only make up a small part of the global migration flows 2. In relation to the population, voluntary migration (as opposed to refugees and asylum seekers) is greatest in middle-income countries such as Mexico, Morocco, Turkey, Egypt and the Philippines. The migration from the poorest countries is mainly to other developing countries.

Migration can have both positive and negative effects on poverty. For the individual, migration is a way out of poverty – an opportunity to improve the living conditions for themselves and their families, as was the case for Norwegian emigrants to America at the end of the 1800s. The consequences for the society at large in the countries of departure can be both positive and negative.

Research shows that well-qualified labour emigrates more than the less qualified. According to the OECD and the World Bank, however, migration of unskilled labour has had a greater potential effect on the reduction of poverty than the migration of skilled labour. In the first place, the unskilled workers send more money home. Possible explanations for this can be that unskilled workers migrate for a shorter period, have a desire to return to their native country and often have to leave their family behind. In addition, the migration of less qualified workers probably leads to a reduction in the unemployment in their native country. The fact that migration for employment purposes can have positive effects for both the country of dispatch and the recipient country is also indicated by a study in which it is estimated that if industrialised countries open their labour markets for a 3 per cent higher share of foreign labour, this would mean an annual economic gain on a global basis of USD 150 billion. This is 1.5 times the gain that is estimated for full liberalisation of the commodity trade 3.

A review by the OECD shows that the vast majority of unskilled migrants in OECD countries are from middle-income countries. Only three per cent of unskilled migrants in the OECD area are from Sub-Saharan Africa, while only 4 per cent are from South Asia. The number of unskilled migrants from middle-income countries in Latin America, East Europe and Central Asia is much higher.

The migration of well-qualified labour for which there is a shortage in their native country can have a considerably negative effect on the development of poverty. The world’s poorest countries are often double losers in international migration: they do not utilise the benefits of migration of unskilled labour and they are hit hard by migration of skilled labour, i.e. brain drain. 4

The health sector is particularly susceptible to brain drain. A number of countries in Africa south of the Sahara have less than 20 nurses per 100,000 inhabitants, while the figure in industrialised countries is 50 times as high 5. In the Philippines, which has actively used migration as a development strategy, 15 per cent of the population with higher education migrate, while only 1.5 per cent of those with only basic schooling migrate 6.

The migration of skilled labour is largely assumed to have a negative effect on the development in the country of dispatch, as is the migration of highly sought after health personnel from Africa to rich countries. However, countries that were poor but are now enjoying high economic growth, such as Taiwan and South Korea, are experiencing that previous migrants are returning home with an education and international experience and contacts. The explosive growth in the IT industry in Bangalore in India is to a large extent driven by Indian IT workers that have returned after staying in the USA and other western countries. This is a good example of positive circular migration. However, it is worth noting that the returning flow takes place after the situation in the native country has changed dramatically.

Migration can contribute to a brain gain if the opportunity to emigrate influences more people in the countries of departure to take a higher education. The major increase in the number of nurses in the Philippines illustrates this. This mechanism does not work, however, in all of the poorest countries, where the opportunities to undertake such education are much more limited.

Another unfortunate consequence of migration of skilled workers, is that the country’s ability to build and maintain good institutions is impaired. There is much agreement on the importance of well-functioning institutions for economic and social development and this field is weakened by the emigration of skilled workers 7.

Most migrants transfer considerable sums of money to relatives back home, and remittances are by far the greatest source of foreign currency for many poor countries. The World Bank has estimated that total remittances from developed countries to developing countries through formal channels were approximately USD 240 billion in 2007. This is more than double the official aid in the world and corresponds to almost two thirds of the total foreign direct investments in developing countries 8. If transfers through informal channels are included, the amount increases by around 50 per cent 9.

The World Bank’s study of international migration and economic development, «International Migration, Economic Development, and Policy» shows that remittances have a clear positive effect on the reduction of poverty in the families receiving the money. Exact measurements of this are difficult, since this entails assumptions of what the migrants would have earned if they had been in their native country, but a great deal of research indicates that this is correct. A survey of 12 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean shows that remittances have had the greatest effect in Mexico and El Salvador, where the migrants come from low-income families. Extreme poverty (less than USD 1 per day) has fallen more than 35 per cent in both countries. The share of the population that lives on less than USD 2 per day has fallen by 15 per cent in Mexico and 21 per cent in El Salvador. The average fall in extreme poverty and poverty for the 12 countries is 14 and 8 per cent respectively. It is difficult to attribute all of this to remittances but the correlation is clear.

While the effect for those receiving remittances is predominantly positive, it is more uncertain what effect the transfers have on economic growth in developing countries. While savings, investments and consumption are increasing, there is also the risk of the exchange rate increasing, with invidious effects for the export revenues and recruitment. The incentives for creating one’s own basis of existence can also be envisaged to be less for some of those with the opportunity to live on transferred funds. There is also the risk of increasing property prices and increased prices of services that are not imported, which is a drawback for the poorest that do not receive money from abroad. As in the same way for large amounts of aid, there is thus a certain risk of increased dependency on remittances from abroad 10.

Remittances can also have consequences for the income distribution in the recipient countries. Where the migrants are mainly from the poor part of the population (which they rarely are), remittances can contribute to a more even distribution. Where they come from families with higher incomes, the income disparities in the country of dispatch can increase. A study conducted in 2007, however, shows that increased remittances generally lead to a fall in the number of extremely poor and that remittances put those living under hard economic conditions and regimes with poor governance in a better position to manage financially 11.

There are also clear correlations between migration and children’s education and health. Children in families with migrants have more opportunities for attending school and staying there longer than children from families with no migrants. The effect is particularly strong for girls, where the share that starts school increases by 54 per cent. For boys, the increase is only 7 per cent. Some of this, but not all, is mainly due to the fact that in principle more boys attend school. Girls from migrant families complete almost two years more of schooling than girls in families with no migrants. Other studies have shown that remittances have a positive effect on outlays for education in midlle- and high-income households, and have a positive effect on outlays for education in households where parents have limited education. Families that receive remittances also have relatively fewer children that need to work. This particularly applies to girls. Studies also show that remittances have a positive effect on children’s health, and the effect is particularly strong in low-income households.

The recipient countries’ systems for controlling immigration partly determine what type of immigrants come to the country. Canada and Australia, for instance, use point systems, where migrants are chosen based on qualifications and can apply for jobs when they arrive in the country. The principle of job offers is also common in Europe. The USA 12 has systems that build on the migrants having job offers before they receive a residence permit and systems that don’t. The Norwegian system for immigration for work purposes is also based on job offers being available before a residence permit is granted. Skilled labour can obtain a work permit that forms the basis for long-term settlement and family reunification, while unskilled works mainly arrive as seasonal workers or for other types of fixed-term stays with no such opportunities.

A number of migrants return home after a while. It appears to be asylum seekers and family members that arrive on family reunification schemes that are least likely to return to their native country. With regard to those who actually do go back, there are strong indications that they obtain qualifications/expertise during their stay that those remaining in their native country do not have. A study of emigrants that return to Egypt shows that they earn almost 40 per cent more than corresponding occupational groups that have not emigrated. Another explanation can of course be that those who left already had skills and resources that the others did not have. The survey also shows that long stays out of the country lead to much higher incomes than short stays, but which country they have been to does not seem to have a bearing 13.

In some cases, it can therefore appear that circular migration works as intended: the recipient countries and companies there earn from having the migrants in work for shorter or longer periods, the migrants themselves have earned money and acquired new qualifications/expertise, the families in the native countries have received money while they were gone and the migrants return home with an increased level of knowledge. Although this works well in a number of cases, however, the factors that made the migrants want to leave their native country are the same as those taken into consideration when they think about returning. If the conditions in their native country have not improved significantly or if they have not managed to attain skills and resources that will improve their living situation considerably, it is likely to take a great deal to get them to return voluntarily.

Considerations of the Commission

An assessment of the Norwegian migration policy from a poverty perspective should build on both an individual perspective and a social perspective. Migration can be a way out of poverty for the individual, and the consequences for the country of origin can be both positive and negative, depending on the migrants’ characteristics as well as the resources that are accruing to the country of origin.

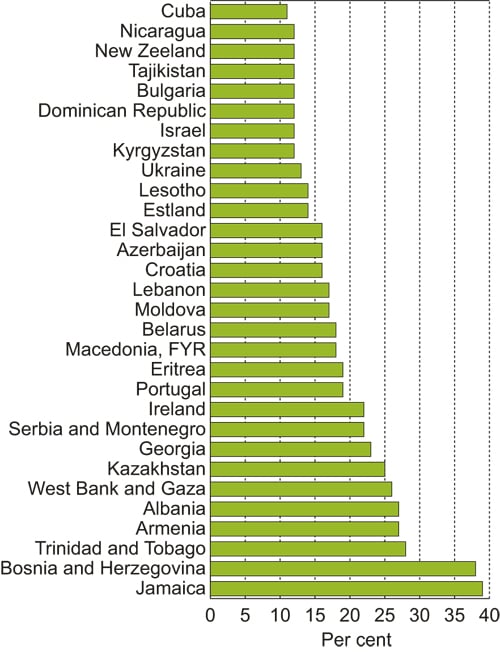

Figure 9.2 Key countries of dispatch. Emigrants as a percentage of the population1.

Source Development Prospects Group, World Bank.

International migration can have a considerably positive effect on poverty reduction. Migration can contribute the most to poverty reduction when there is unskilled surplus labour that emigrates from poor countries, but can have a negative effect when it is mainly skilled surplus labour that emigrates. There are strong indications therefore that the benefits of migration are unevenly distributed. As it stands today, poor countries are double losers in international migration. The migration of unskilled labour from the poorest countries is very limited, but poor countries are overrepresented among those that have experienced a large emigration of well-educated inhabitants. The Commission’s proposal for initiatives is aimed at rectifying such imbalances.

Commission member Kristian Norheim does not support this description.

9.2 A global perspective on migration

9.2.1 Migration and decent work

Increased migration is closely linked to the increasing globalisation. Reduced transport costs have enabled many to relocate abroad. However, potential migrants have in no way had the same opportunities for freer movement across country borders compared to the wave of liberalisation in the capital markets at the start of the 1990s. There are still stringent restrictive rules in place for the international migration of labour and the rights of migrant workers are considerably poorer than for example the strong legal protection that foreign investments have had.

A substantial increase in illegal immigration has taken place in recent years. The ILO estimates there to be between 15 and 30 million illegal immigrants on a global basis, and the number is increasing 14. Many of the migrants take jobs that the local population does not want. They are overrepresented in occupations with major health risks and often fall outside social schemes. Based on this, the ILO has strengthened its efforts for decent work. This agenda has four strategic goals: work opportunities, workers’ rights, social protection and safety, as well as dialogue and third party collaborations. The goals apply to all workers, men and women, both those that are employed in the formal and the informal sectors.

One of the hot topics in the debate surrounding the protection of migrant workers’ rights and the rights of workers in developing countries is how strong the legal protection should be. Many developing countries are opposed to legalising widereaching economic and social rights as they think it will price them out of the global markets, prevent infant industries from developing and thereby stopping or obstructing economic growth. It is claimed that rich countries use the requirement for decent work and labelling requirements for goods as a cover for protection of their own markets and products. Further details of this problem are given in the chapter on investments.

9.2.2 Human trafficking and illegal migration

International human trafficking is closely connected with many of the same factors that give incentives to seek work abroad. In addition, many children are abducted or sold and sent away from their native country. Adults imagine that work in rich countries is a way out of poverty and that they will get work once they get there. The middle men ensure that they get into these countries and many put themselves in great debt to them. They subsequently end up in prostitution or slave work in order to pay back the cost of the journey. Human smuggling and human trafficking of women has become a major industry that profits extensively from the world’s poor and most vulnerable. It is estimated that this often organised criminal activity is second only to the illegal trade of arms. Employers in many countries use such illegal labour, which is cheap, easily replaced and can easily be controlled using violence or threats to them or their family. The epicentres for human trafficking are changing. Earlier, most victims were from South and East Asia. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Mafia took over much of this area in Eastern Europe. There is a strong international focus on curbing human trafficking. A number of UN organisations, OSCE, the Council of Europe and ILO are working on this issue, as are the IOM, many NGOs and various countries’ immigration and police authorities, as well as Interpol. However the incentives to escape poverty and to earn money for those who want it, are strong. Substantial efforts are therefore still required to terminate human trafficking. A formalised labour immigration system from developing countries, including for women, can help to reduce their vulnerability and the risk of ending up as a victim.

9.2.3 Increased international competition for labour

The increase in the migration of skilled labour started on a global basis in the 1990s and is still growing. Persons with a high education migrate relatively more often than those with little or no education (See table 9.1). For many poor countries, the share with a high education that has moved to rich countries is very high. Some African countries are experiencing a dramatic brain drain: in a number of countries, one out of four with a high education live outside the country borders. (See table 9.2)

According to a study, 15 a number of factors can be regarded as the basis for the increased migration of highly qualified labour. First, the global knowledge economy is driven by technological progress, rich countries compete with each other for the best heads and have a need for specialist expertise. This is particularly true within engineering and scientific disciplines, where rich countries experience recruitment problems. For example, a sixth of the employees in the American IT sector are immigrants 16. Second, the population in western countries is becoming increasingly older. This has consequences for the labour market since rich countries will need more employees in health and social services. The high costs linked to an ageing population can also lead to rich countries wanting to attract highly paid migrants, which through tax can help to pay for pension and health services. Third, the globalisation of production and trade is contributing to more workers relocating.

Highly qualified labour in poor countries can have strong incentives to migrate. Low salaries, poor working conditions, lack of resources and limited opportunities for further education and a career, as well as much better conditions in rich countries are often deciding factors 17.

Table 9.1 The best educated have the greatest tendency to emigrate*

| 1990 | 2000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of origin | Compulsory schooling | Upper secondary | Compulsory schooling | Upper secondary |

| Mexico | 6.5 | 10.4 | 9.5 | 14.3 |

| Philippines | 1.1 | 12.8 | 1.4 | 14.8 |

| India | 0.1 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 4.2 |

| China | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.1 | 4.2 |

| El Salvador | 8.2 | 32.9 | 11.2 | 31.5 |

| Dom. Republic | 3.8 | 17.9 | 5.8 | 21.7 |

| Jamaica | 11.0 | 84.1 | 8.3 | 82.5 |

| Colombia | 0.5 | 9.2 | 0.8 | 11.0 |

| Guatemala | 2.1 | 18.2 | 3.5 | 21.5 |

| Peru | 0.3 | 5.6 | 0.7 | 6.3 |

| Pakistan | 0.2 | 6.1 | 0.3 | 9.2 |

| Brazil | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 3.3 |

| Egypt | 0.2 | 5.3 | 0.2 | 4.2 |

| Bangladesh | 0.1 | 2.3 | 0.1 | 4.7 |

| Turkey | 4.2 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| Indonesia | 0.1 | 6.2 | 0.1 | 2.0 |

| Sri Lanka | 0.8 | 24.8 | 1.9 | 27.5 |

| Sudan | 0.0 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 5.6 |

| Tunisia | 4.6 | 12.3 | 4.2 | 9.6 |

* Percentage of the population that immigrated to OECD countries, by level of education

** Kapur, Devesh et al (2005) The Global Migration of Talent: What Does it Mean for Developing Countries, CGD Brief http://www.cgdev.org/content/publications/detail/4473

Source Center for Global Development**

9.2.4 International processes

The Global Commission on International Migration, was established in 2003. The Commission submitted its report in 2005. In September 2006, the UN arranged the first high level dialogue on international migration and development. One result of this meeting was the establishment of the global migration forum. The forum had its first meeting in Brussels in the summer of 2007 and its next in Manila in October 2008. The three key topics at the Manila meeting were migrants’ human rights and development, forms of legal development-promoting migration and coherence between the migration and development policy at the institutional and political level. The migration issue is brought into the UN through the Secretary General’s Special Representative for Migration and Development, Peter Sutherland, who took part in the preparatory work for Manila and at the conference.

Under its EU presidency, France will arrange a ministerial meeting on migration and development in Paris in December 2008. Preparations have been made for this with participation from developing countries through three preparatory conferences: in Morocco on legal forms of migration, in Burkina Faso on illegal migration and in Senegal on the development effects of migration. In recent years, the EU has undertaken a more holistic approach to the policy areas of migration and development.

As a global phenomenon, migration requires both global and regional collaboration. The EU is the most important participant in Europe. Norway’s association with the EU through the EEA agreement and the Schengen cooperation means that the policy developed by the EU can also have a bearing on the decisions in Norwegian policies. One example of the EU’s effort to harmonise practice and procedures in this area having a bearing on Norway is the Directive on Returns, which Norway will be bound by through the Schengen agreement. This means that Norway must make certain changes to laws and regulations that reinforce the rights of citizens in non-EU countries that are sent back because they are staying in Norway illegally.

9.2.5 Services trade

The service sector makes up around half of the GDP in developing countries, compared with approximately 60 per cent in developed countries. The sector is also among the fastest growing in many countries and is also extremely important for enabling growth in other sectors 18. The Uruguay round extended the trade negotiations in GATT and subsequently the WTO to also include services. However, most of the focus is on the services where rich countries typically have the advantage, such as banking, insurance and information technology. Poor countries normally have a surplus of low-educated labour, so the liberalisation of the services trade that is intensive in its use of low-educated labour would therefore represent an export opportunity for poor countries. Many types of services are difficult to trade without moving the labour to the place where the service is supplied. There is a close connection here between the countries’ trade and immigration policy. Calculations show that employment in rich countries of some of the surplus that poor countries have of low-educated labour could have given incomes that are many times higher than the gains to be had by liberalising the capital markets in these countries. Restrictive regimes for the movement of labour prevent such development 19.

Table 9.2 Percentage who live abroad of those with university and university college education from various African countries

| > 50 % | Cape Verde, Gambia, Seychelles, Somalia |

| 25 – 50 % | Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ghana, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Nigeria, Sao Tome & Principe, Sierra Leone |

| 5 – 25 % | Algeria, Benin, Burundi, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Chad, Comoros, Congo, DRC (previously Zaire), Djibouti, Ethiopia, Gabon, Guinea, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Nigeria, Morocco, Rwanda, South Africa, Senegal, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe |

| < 5 % | Botswana, Lesotho, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Egypt, Libya, Namibia |

Source Center for Global Development

The developing countries have made demands for increased trade in services. Their key requirement is the right to short-term migration for employment purposes – 3 months to 5 years – either as self-employed, internally between different parts of the company, or sent by a company to carry out short-term duties. Such short-term migration for work purposes – which Mode 4 in the GATS negotiations applies to – does not include seeking work in another country or permanent migration. It will therefore only cover a small part of total migration.

India has in this regard formulated a proposal with four points .

Provide free and accessible information on the opportunities for short-term labour migration

Treat labour migrants equally regardless of their country of origin

Standardise and harmonise qualifications and experience by means of agreements

Remove all obstacles for the free movement of skilled labour, the opportunity to compare wage conditions and qualification requirements

Short-term or more permanent labour migration and service trade represent both an opportunity for poor countries to reap the rewards from the economy in rich countries and for the rich countries to get the necessary top-up of labour. Services trade and temporary labour migration will also help to solve the problem of providing enough labour for care services in countries with a relatively small work force. Tax revenues from services trade and labour migration will also be able to finance pensions and care services.

Many OECD countries have for a number of years been open to a certain temporary/short-term labour migration, either on a broad basis as is the case for some continental European countries, or mainly on a seasonal basis, as is the case for Norway. Short-term labour migration in Norway had a significant scope up to 2003 and was the largest category of work permits that were granted for many years. After the EEA expansion to many of the countries from which the seasonal works emanated, the scope has been significantly reduced. The Commission believes that either the authorities or the labour organisations have placed sufficient emphasis on ensuring the short-term immigrants’ employment and wage conditions.

With the expansion of the EU and the new and broader EEA labour market, the situation has changed fundamentally, whereby the short-term labour migration has increased in breadth and scope and the discussion on the EU’s service directive on how to ensure that tariff agreements are made valid for foreign companies in Norway and how to generalise (more) tariff agreements have become topics on the political agenda.

9.2.6 Women in international migration

Women make up almost half of all migrants worldwide. The share of women increased from 46.7 per cent in 1960 to 49.6 per cent in 2005. Around 95 million women are migrants today compared with 85 million in 2000. The World Bank study «Women in International Migration» shows that there are clear differences between women and men with regard to reasons for migration as well as in relation to how the money they send home to their family is spent.

The presence of family in the country a person moves to is a relatively strong motivation factor compared to the majority of macroeconomic and political factors. In addition to this, men have a strong motivation to have female family members living in the country they are moving to, while it appears that women’s network at home plays a relatively stronger role for them.

The report also shows that the tendency that is seen in many countries for women to be most involved in the direct supply of food for the family and men most in the production of food and other goods for sale, means that men’s migration entails an immediate fall in the family’s total income-generating production. This is compensated, however, in the next round by money sent home. Women’s money that is sent home appears to increase the total family income the most. The fact that they leave affects the direct supply of food more than the family’s income-generating activities. Some of this disappearance of food production must however be compensated through buying food.

Another important effect of women’s migration appears to be that the share of family income that is spent on children’s education is lower than in households where the man is the migrant. This implies that men place less emphasis on children’s education than women (and that the children often travel with the women). This is supported by findings that indicate that households with a female head that receive remittances increase the share that is spent on housing, durable goods and health services and less on food, while this is not the case in households where the man is at home 20.

Human trafficking is the negative side of female migration. Both women and young girls are exploited often after being smuggled into a country and ending up in debt to the men behind it. They then often end up as domestic help on slave contracts or as prostitutes.

Considerations of the Commission

While there has been a strong liberalisation pressure for freer flows in the capital markets, extremely restrictive regimes have been applied to the movement of labour. Some developing countries have therefore made demands in the WTO to liberalise the trade in services that entail relocating people from one country to another (mode 4 in the GATS negotiations) and want to enable an increase in short-term labour migration. The Commission recommends that Norway tries to a greater extent to comply with the developing countries’ proposals on the liberalisation of movement of labour in the GATS negotiations. Norway should take the initiative to report on how labour migrants can be treated more equally regardless of their country of origin.

Experience shows that it is difficult to set conditions for the migration of labour to be circular. A significant number of those arriving will want to remain in the country. Many migrants have, however, both education and expertise that is sought after in their native country. Migrants that want to move between their native country and country of work now face a number of challenges. In Norway, the risk of losing permission to stay on in the country during longer trips away from Norway can prevent migrants from travelling home. The Commission believes it is important that more is done to make it easier for those who wish to use their experience in their native country.

The Commission would like to point out that women are particularly affected by poverty and a shortage of work in their native countries. Women constitute a large share of the world’s unskilled labour and make up more than half of the world’s labour migrants. Irregular migration and human trafficking must be regarded in context of a lack of opportunities for legal migration. The more closed the legal migration opportunity is, the larger the market for irregular migration. Women are particularly vulnerable to exploitation in a migration situation. Many of the asylum seekers and the poorest labour migrants resort to human smugglers to get into a country where they can seek asylum and work. Many incur large debts in order to travel, and the routes are often perilous. Human smuggling and human trafficking of women has been a major industry that profits substantially from the world’s poor and most vulnerable, often with promises of residency and work in developing countries. A formalised labour migration system from developing countries, including for women, can help reduce this vulnerability. The Commission’s assessment is that a more liberal migration and refugee policy with a clear gender perspective will be a key tool in the fight against human trafficking and global poverty.

Kristian Norheim does not support these views.

9.3 Immigration to Norway

9.3.1 The White Paper on labour immigration

In April 2008, the Government presented a new report to the Storting on Labour Migration (Report no. 18 to the Storting (2007 – 2008)) 21. The basis of the report is that in light of the demographic development, Norway among others has a need for immigration in order to cover future labour needs. It provides a thorough review of this need and takes its basis in the fact that it can mainly be covered in Norway. Mobilisation of unused domestic capacity is central together with continued immigration from the EEA area, but some immigration from countries outside the EU/EEA area may be necessary. The following includes references to the main points in the report.

9.3.2 Migration flows to Norway

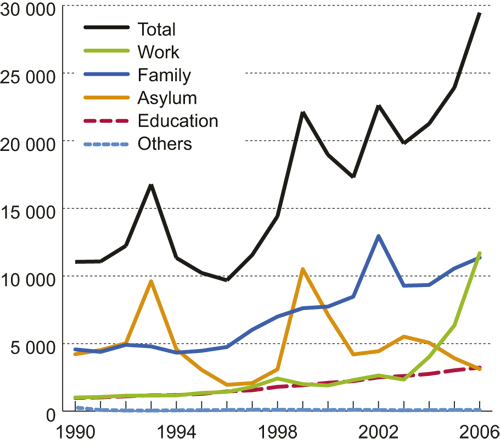

Immigration to Norway in recent decades can mainly be linked to the main migration flows: work, flight, family and education. Between 1990 and 2006, more than 284,000 persons of non-Nordic citizenship immigrated to Norway. Around 43 per cent arrived as a result of family immigration, 29 per cent as refugees, while 16 per cent is due to labour migration. A total of 11 per cent arrived in Norway for educational purposes 22.

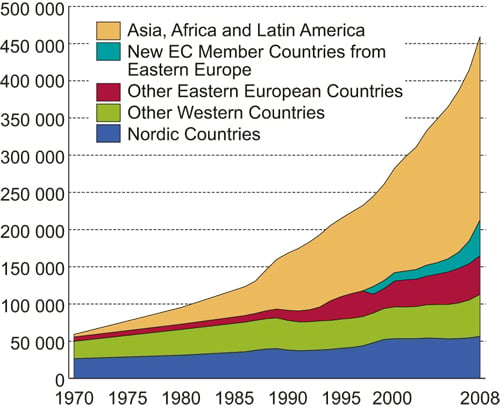

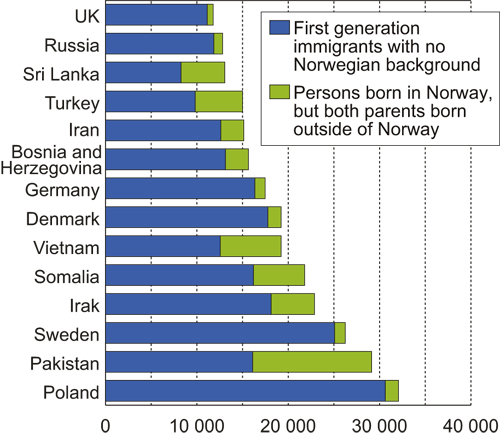

Today the immigrant population 23 in Norway consists of 415,000 persons, which corresponds to 8.9 per cent of the population. The three largest immigrant groups in Norway have backgrounds from Pakistan, Sweden and Iraq. In 2006, around three out of four immigrants had backgrounds from non-western countries. These constitute 6.6 per cent of the population. The corresponding figure in 1986 was 1.1 per cent 24.

9.3.3 Labour market in Norway

Norway currently has unused labour resources among those who have already immigrated to the country. The share of first-generation immigrants in employment is around 60 per cent, compared with 70 per cent for the population as a whole. Non-Western immigrants have a lower employment rate than others. Immigrants from Africa have an employment rate of 45.2 per cent. The lowest employment level is among immigrants from Somalia, with 31.7 per cent. Next are the immigrants from Afghanistan and Iraq, with an employment rate of slightly more than 41 per cent in each group. The low employment rate is partly due to the fact there are many refugees from these countries that have lived for a short period in the country, that they have a low level of education and women have a low labour force participation. There are also immigrant groups with a long period of residence in Norway with a low labour force participation rate. Immigrants from Pakistan currently have an employment level of 46.3 per cent, which is mainly due to extremely low employment among women with a Pakistani background (only 29.1 per cent employment for women, 62.2 per cent for men). The figures also indicate a lack of integration and discrimination in employment 25.

Figure 9.3 Immigration background in the Norwegian immigrant population 1990 – 2006

Source Statistics Norway

Textbox 9.1 Migration to Norway in a historical perspective

The labour migration from developing countries, e.g. Pakistan, started at the beginning of the 1960s, but has been modest since the introduction of the «immigration freeze» in 1975. From that time, family immigration from the same countries increased considerably. In recent years, the emphasis and a larger share of the family immigration has been women, e.g. from Thailand, Philippines and Russia, that enter into marriages with Norwegian men with no immigrant background. The accepting of refugees from developing countries, particularly from Vietnam and Chile initially, also started in the mid 1970s. There was a strong increase in the number of asylum seekers in the mid 1980s, including from countries such as Iran and Sri Lanka. In the 1990s, war refugees from the Balkans were predominant. A large number of these returned home, initially to Kosovo. Since the end of the 1990s, many asylum seekers from countries such as Iraq, Somalia and Afghanistan have arrived. Due to favourable lending and scholarship schemes, there has been a degree of immigration for education purposes since around 1980, including from countries in Asia and Africa.

Source: Statistics Norway

A study from 2002 shows that the income of non-western immigrant families is 25 per cent lower on average than the average income for the population as a whole. For an immigrant family that has lived in the country for five years the income gap is half of this. A substantial share of immigrant families is represented in the lowest income class. A total of 36.7 per cent of the families from East Europe and 41.5 per cent of the families from Asia, Africa and Central and South America had an income after tax of less than NOK 199,000, while this share was 5.2 among non-immigrant families. The difference can be explained by the fact that non-Western immigrants are overrepresented in the hotel industry, restaurant industry and cleaning jobs, i.e. low paid work that does not require much education.

Figure 9.4 Immigrant population in Norway by country background. 1970 – 2008

Source Statistics Norway

The specialist quota enables Norway to import specially needed labour, but the quota is only used to a limited extent (see above). As Norway does not systematically register education levels upon immigration, there is uncertainty surrounding the level of education of immigrants to Norway, and it is difficult to say whether the immigrants to Norway represent a brain drain for the country of dispatch. The figures that are available suggest that the level of education among the immigrants from most country groups is lower than the average in Norway for corresponding age groups. The distribution of occupational groups shows that a relatively high share of the non-Western wage-earners are found in the «other occupations» group, which mainly covers occupations with no special educational requirements. A total of 23 per cent of the non-Western immigrants are in this category compared with 6.3 per cent of wage-earners in total (with specified occupation details). On the other hand, the Western wage-earners had a correspondingly high share in academic positions of 20 per cent. For wage-earners as a whole, this share was 11.3 per cent and 6.7 per cent for non-westerners 26.

Figure 9.5 The 15 largest immigrant groups in Norway. 1 January 2007. Absolute figures

Source Immigrant population, Statistics Norway

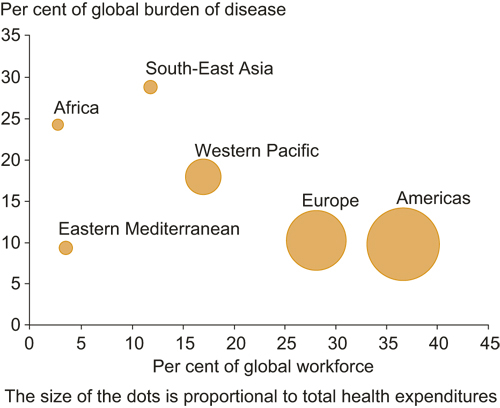

9.3.4 The need for health personnel

On a global basis, there is currently a dramatic lack of qualified health personnel. The World Health Organisation believes there is a global need for around 4.3 million more health workers. Of these, 2.4 million should be doctors, nurses and midwives. Most precarious is the lack of health personnel in the countries with the greatest health problems. Africa is in the unfortunate position of having around a quarter of the world’s total burden of illness, while the continent only has 3 per cent of the world’s health workers and 1 per cent of the world’s total economic resources in the health service area (including aid) 27. It is against this backdrop that Norway has committed to adopt a policy that can stem the flow of qualified health workers from poor countries 28.

In 2004, the total number of employees in the health and care sector in Norway was slightly more than 230,000. In May 2006, 2.5 per cent of all posts in the sector were vacant. In the fourth quarter of 2006, there were 12,000 foreign health workers in the health service in Norway. Figures from the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision show that the immigration to Norway by health personnel directly from Africa is small (around 5 doctors and 5 nurses per year). Immigration by authorised doctors from countries outside Sweden and Denmark (mainly East Europe) is around 300 per year. Norway’s contribution to the brain drain from developing countries in this sector therefore is most likely to be related to the domino effect that is believed to take place when Norway recruits from a country in Europe, and this country in turn recruits from other countries that finally employ personnel from developing countries 29. However, these are effects that are difficult to document.

As with most other European countries, Norway is facing a growing elderly population. The increase in the number of the elderly will gradually start to show in 2013, and will be particularly challenging after 2025. There will be fewer people in employment per person in need of nursing. In 2005, every fourth person was aged 55 or older, while every third person will be older than 55 in 2025. The demographic changes are expected to lead to increased demand for nursing and care services. Labour market projects for health and social welfare personnel in Norway show that there could be a lack of auxiliary nurses and care workers particularly after 2025 30.

Table 9.3 Employment in percent by region of origin and length of stay. Share of persons between 15 and 74 that were in employment in the 4th quarter of 2006 in Norway.

| Region of origin | Less than 4 years | 4 – 6 years | 7 years and more |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immigrants, total | 53.4 | 60.3 | 62.7 |

| Nordic countries | 75.6 | 79.5 | 72.1 |

| West Europe | 69.4 | 78.1 | 70.3 |

| New EEA countries | 73.3 | 75.4 | 66.6 |

| East and Central Europe | 46.0 | 63.9 | 62.6 |

| North America and Oceania | 49.1 | 64.1 | 65.7 |

| Latin America | 48.2 | 63.7 | 67.0 |

| Asia | 38.5 | 53.4 | 58.1 |

| Africa | 34.5 | 46.6 | 50.7 |

Source Statistics Norway

In the short-term, however, Norway has a sufficient intake of most higher level health education studies to meet the demand for labour in the nursing and care sector. The challenge is the falling interest in advanced training 31.

Measures that regulate the migration between individual countries will have a limited effect in a globalised world. The main problem in the health personnel crisis is that there is a global deficit of health workers and that the demographic trend in many European countries and countries in the OECD is, as in Norway, showing an increasingly elderly population. It is not therefore very helpful that some countries develop a responsible policy for counteracting the loss of health resources in the South if many others enable recruitment. This highlights the need for international guidelines.

Figure 9.6 Percentage of the world’s health workers in relation to the share of the world’s sickness burden per WHO region

Source WHO, 2008.

Arrangements have been made to develop compensation mechanisms for the country of dispatch that can be initiated when qualified personnel from developing countries come to rich countries such as Norway to work 32. Calculations from the African Union show that poor countries bear an education cost of USD 500 million for the qualified health personnel that migrate to rich countries. In other words, subsidising from poor to rich countries. Various compensation schemes have been suggested: sharing tax revenues, an extra charge in addition to the visa charge that is directly transferred back to the native country, continued tax obligations in the native country, and education support that must be paid back in the event of migration. However, such compensation schemes entail major practical challenges with regard to administration and organisation. A particular challenge is how the compensation scheme can factor in that health personnel after a relatively short period of time can leave the country that has basically compensated the donating country.

Figure 9.7 Migration of well-qualified labour creates problems in developing countries. It can also provide valuable experience for those moving and remittances to families back home.

9.3.5 Labour immigration to Norway

Norway receives very few labour migrants from poor countries. Of the 34,000 that immigrated to Norway to work during the period 1990 – 2005, 27,000 (79 per cent) were from Europe 33.

Norway has restrictive rules for labour immigration. All non-Nordic 34 citizens must have a work permit in order to work in Norway. As a main rule, citizens of non-EU countries must have their first work permit granted before arrival in the country 35 and they cannot get a work permit if there is available labour of the relevant type in the country or within the EEA/EFTA area. Nordic citizens and EEA citizens can travel to and apply for work in the country without any such prior permission. There are three different types of work permit for non-EU citizens.

The Labour Migration report divides the labour immigrants from non-EU countries into five groups. a) Highly qualified specialists and key personneland b) Skilled –can have family reunifications and opportunities for long-term stays. c) Newly qualified –can have a work permit for 6 months while they are applying for work within the first two groups (and the families of students can work full time). d) Seasonal workersget work permits for 6 months but not the opportunity for family reunification or long-term stays. e) Unskilledget permits as the need dictates and this scheme is aimed at special needs for labour in Norway and special geographic regions (in the first round people from the Barents Sea Region in Russia). However, there is a small possibility for the temporary immigration of persons from developing countries as part of aid projects in order to test schemes with circular migration. A dedicated internet portal will be created containing all relevant information for labour migration and there is a wish to involve the Norwegian Foreign Service more actively in information work on work opportunities in Norway.

It will also be easier for labour immigrants to find work in Norway. Those employed in international companies and those belonging to groups a) and b) above will be able to start working before the work permit is obtained.

Textbox 9.2 New initiatives in Sweden

In October 2006, a committee of parliamentarians issued the report «SOU 2006:87 Work-related Migration to Sweden – recommendations and consequences». The committee recommended, amongst other, the following:

Work-related immigration to Sweden from a third country shall continue to be regulated. The main rule should be that an offer of employment is in place and that stay and work permits should be obtained prior to arriving in Sweden.

Temporary work permits can be given for a period of up to two years with possibility of extension for another two years, when the labour demands cannot be covered by domestic labour and labour from the EEA/EEC area. After four years, a permanent stay and work permit may be given.

A possibility of staying three months in Sweden on order to seek employment should be given. A condition should be that there is demand for labour in Sweden within the sector in question.

Foreign students who have completed parts of their studies or completed one semester as a guest student at a research program should be able to seek stay and work permits in Sweden.

The new Government was of the opinion that parts of the suggestions did not offer sufficient flexibility and efficiency and suggested additional changes. Among the most central recommendations is that evaluation of the labour market situation by the authorities is cancelled, something which means that the authorities do not evaluate the labour demands before a stay and work permit is given. Instead, a requirement that the position shall have been advertised within the EEA/EEC area before it can be given to a person from a third country has been imposed. The scheme with permits for seasonal workers will also be abolished. These workers shall now be able to obtain work permits within the regular system for the length of the contract. It is also suggested that rejected asylum seekers who have worked for more than six months in Sweden shall be able to apply for stay and work permits in Sweden if the person in question fulfils the regular requirements.

With these suggested changes, the Government wishes to create a demand-driven system for work-related immigration where the employers themselves shall evaluate the needs for recruitment from third countries, without the need for approvals from the authorities. Salary levels, social rights and other labour conditions shall be equal to that of workers living in Sweden. These suggestions also entail that the same framework for stay and work permits applies to all work-related immigrants, irrespective of level of skills and competence.

On March 27th, the Swedish Government put forward a «lagrådsremiss» based on these recommendations. It will then put forward a law proposition to the Parliament where the changes are proposed to be in effect from 15 December 2008.

In Sweden, work-related immigrants and their families have the right to free language lessons if they lack basic skills in the Swedish language. The courses are offered to immigrants who are registered in the population register, something one becomes if ones stay permit is for at least one year. The extent of the language course is a maximum of 525 lessons. If literacy lessons are needed, these are considered additional.

From the poor developing countries’ point of view, one of the most important proposals in the Labour Migration report is perhaps that rules will be drawn up in relation to the active recruitment of persons with higher education from countries that badly need these themselves. Such work is already underway in the area of health, but the brain drain problem also applies to other occupational groups such as engineers, economists and many categories of university staff. No obstacles should hinder these being able to apply for work in Norway on their own, but Norway shall not actively contribute to draining developing countries of specialists. Norway is a small labour market and the wage levels here are not particularly attractive for people with a higher education, but the signal effect of such a scheme is important. When Norway is also working actively to create international standards to counteract such active recruitment, the effect can be noticeable. However, the report does not say anything about whether the rules to be created will only apply to the public sector or whether restrictions will be placed on all activity that recruitment agencies in Norway carry out abroad.

Another important proposal that is a plus for developing countries is that a study is to be carried out on how sending money home can be made easier and cheaper. This is in light of the fact that it is very expensive to send money home from Norway.

9.3.6 Immigration to Norway for education

Norway receives few students from poor countries. Seventy per cent of those who immigrated for educational purposes in the period 1990 – 2005 were from non-Western countries, but it is particularly students from China, Russia, the Philippines and Poland that received education permits 36.

There are few researchers from developing countries in permanent scientific posts in Norway, but a relatively large share of the research recruits come from countries outside the OECD area. Half of the foreign researchers at universities, university colleges and research institutions come from OECD countries outside the Nordic region. China, Russia and Iran are the most important countries of origin for researchers with non-Western backgrounds. While 90 per cent of the foreign researchers in permanent scientific posts have backgrounds from OECD countries, 40 per cent of foreign research recruits are from countries outside the OECD area.

The compressed Norwegian wage profile makes it more attractive to be a researcher in training posts than a senior researcher in Norway. The latter can achieve considerably higher salaries in other countries. The Norwegian doctorate scheme is good compared with other OECD countries, and Norwegian doctorate stipends that are announced internationally attract a high number of applications. However, the Norwegian salary system leads to a risk that foreign research fellows «leak» to institutions in other countries when they are ready to go over to higher scientific posts.

Each year, the quota scheme enables 1,100 students from developing countries and Eastern Europe to study in Norway, mainly at MSc and doctorate level. The expressed goal of the support scheme is to give the students the relevant qualifications to benefit their native countries when they return after completing their studies. Students that do not return to their native country have to pay back the stipend as a student loan. Nevertheless, many quota students choose to stay in Norway or travel to another country instead of their native country after completing their studies.

Table 9.4 Persons that immigrate to Norway to study. 1990 – 2005. Ten of the most common country backgrounds

| Germany | 2 427 |

| China | 1 885 |

| Russia | 1 654 |

| USA | 1 551 |

| Philippines | 1 450 |

| Poland | 1 013 |

| Lithuania | 803 |

| Ghana | 768 |

| Latvia | 676 |

| Romania | 633 |

Source Statistics Norway

Since the academic year 2006/07, a change in legislation has made it possible for international students to work in addition to studying. The students are now given a general permit to work part-time (max. 20 hours per week) together with the residence permit.

9.3.7 Refugee flows to Norway

At the start of 2007, 125,100 persons with a refugee background lived in Norway, which corresponds to 2.7 per cent of the population as a whole. In ten years, the number of persons with a refugee background has almost doubled. In 1997, refugees from the Balkans, Vietnam and Iran made up the largest groups in Norway, while ten years later most refugees are from Iraq, Somalia and Afghanistan. In 2005, Norway received 5,400 asylum seekers, of which around 10 per cent were granted asylum. In addition, 35 per cent of the asylum seekers were granted residence permits on humanitarian grounds. Each year, Norway receives a specific number of quota refugees. In 2007, the figure was 1,200. In 2007, in collaboration with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Norway also accepted 1,200 refugees from countries where they had first applied for asylum, for resettlement here. The Norwegian Directorate of Immigration assesses and grants such permits and takes both security and integration aspects into account. The Directorate also prioritises people with a background in health disciplines due to the need for labour in this sector. As this applies to persons that have already been banished from their native country, it is not considered to be contrary to the goal of avoiding active recruitment of health personnel from developing countries. There is a certain competition with other OECD countries for this labour.

9.3.8 Irregular migration

There are no accurate figures on the scope of irregular migration to Norway. In 2005, only 7 per cent of asylum seekers in Norway had legal travel documents when they applied for asylum, and 90 per cent applied for asylum at police stations within the country, not at the border 37. There are no programmes in Norway that make it possible for illegal immigrants to obtain a different status. Human smuggling to prostitution and slave work both of women and children are also found, however, in Norway, and special measures have been implemented for such victims 38. Among other things, they can obtain a special residence permit for up to six months – a reflection period where they will get practical follow-up and help – when they have no other basis for legal residence. In 2007, 31 persons were granted a reflection period of six months, which is an extension of the reflection period in relation to previously.

9.3.9 Situation for the asylum seekers

Many asylum seekers stay for long periods in Norwegian reception facilities. Those who are unable to master the language, or have no relevant work experience often have problems in securing a footing and job opportunities. Many perceive a long-term asylum stay as depressing and destructive, and are poorly prepared for integrating in Norway or for any voluntary or forced returns. For the final group, not managing to secure an income or the skills to support their family is also problematic. Experiences in Denmark are relevant here. Through a voluntary organisation, asylum seekers are offered short vocational courses, Want2work, and/or job experience placements. The experiences have so far been positive both with regard to their time in Denmark and in relation to finding work upon their return. The Policy Coherence Commission does not, however, give any consideration to any other aspects of Danish immigration and asylum policy.

9.3.10 Integration policy

In October 2006, the Government presented a plan of action for the integration and inclusion of the immigrant population. Efforts to combat racism and discrimination are a running theme in the plan, which has the following four main focus areas: work, upbringing, education and language, equality and participation.

The plan of action details the focus and measures to help find individuals work. The local authorities are named as the key players in the settlement and integration of newly-arrived immigrants and the plan of action states that the Government will strengthen the integration surplus of local authorities that settle refugees and their families.

An important initiative that the Government proposes is to grant NOK 42.6 million to Norwegian language teaching for asylum seekers that are waiting to have their application processed. Asylum seekers that stay in ordinary reception facilities should receive up to 250 hours of Norwegian language teaching.

The immigrant population is overrepresented among persons with a continual low income. The effort must be aimed at labour migrants as well as asylum seekers and must therefore also be regarded in conjunction with the Government’s plan of action to combat poverty.

In connection with the launch of the plan of action, the Ministry of Labour and Social Inclusion drew up an evaluation of the Norwegian integration policy with the emphasis on anti-discrimination. The report was prepared by the Migration Policy Group and was presented in November 2007. The results from the evaluation are built on the results from the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) based on 140 indicators. Norway is in eighth place on this index, out of 28 countries; the 25 EU countries plus Canada, Norway and Switzerland. Norway received a high score for giving immigrants access to the labour market, on human family reunification policy, on its long-term approach to stays and with regard to political participation. We are much weaker when it comes to anti-discrimination and access to citizenship for instance. It is difficult to become a Norwegian citizen and Norway does not permit double citizenship 39.

The Government states in the Labour Migration Report that it is working on introducing Norwegian language teaching for labour migrants, with a start package that includes information on rights and obligations, by improving the schemes for approving foreign higher education and by continuing NGO’s work aimed at immigrants.

9.3.11 Remittances from Norway

A study of remittances from Norway highlighted that there is no accurate information on the size of the amounts that immigrants in Norway transfer to their native country 40. The transfers contribution to reducing poverty and facilitating growth is influenced by how the money is transferred and how much money the recipient is left with. The costs of transferring NOK 1,000 from Norway vary between 5 and 25 per cent. Research shows that remittances have the best development effect if they are sent via financial institutions such as banks or micro credit organisations where credit can also be created for parties other than the recipient. However, the banking industry is often poorly structured in many developing countries and there is often great uncertainty linked to time and costs when using the services in this sector. A remittance to Pakistan can, for instance, take between 11 and 23 days, and the transfer often has hidden costs. It is therefore uncertain how much actually reaches the recipients.

Compared to Europe, Norway has a relatively strong set of rules for remittances. This means that there are few alternative remittance services, which means a lack of competition and high price. Informal transfer services (‘hawala’ is a commonly used general term) are not legal in Norway. For remittances to countries that do not have an effective banking industry or offices for remittances, however, hawala can be the only option for sending money. Hawala operators are legal in the UK, Sweden and Denmark, but illegal in Spain, the Netherlands and Norway. Some of the hawala providers that operate in the irregular market in Norway are publicly registered companies in countries with less restrictive sets of rules.

Somalia is one of the countries that is most dependent on remittances. There is currently no legal way of transferring money to Somalia. The possibilities for sending money to Iraq are also very limited, and to the Kurdish areas in the north the hawala services are the only option at present. According to the Norwegian National Authority for Investigation and Prosecution of Economic and Environmental Crime, immigrants from Afghanistan, Iran and Sri Lanka use such companies. (Ref. Carling et al 2007). The lack of legal remittance services can lead to reduced remittances and thereby less poverty reduction in the country of origin since the migrants risk criminalisation and because the transfer costs will probably be higher.

The stringent set of rules is motivated by the desire to counteract tax evasion, money laundering and the financing of terrorism. Since hawala services are illegal, and therefore not supervised, there is no incentive to implement routines that will make it easier to trace remittances. Some of the established international hawala operators, however, have such routines in place. This information does not benefit the Norwegian authorities as long as the hawala operators are illegal in Norway. Statements from the police in Norway and the financial authorities indicate that they realise the lack of transparency that the prohibition entails is a major problem, and finding solutions to legalise the schemes is desirable.

Considerations of the Commission

Norwegian policy has a clear potential for improvement with regard to exploiting synergies between the labour and immigrant policy and the development policy’s goal of reducing poverty. Migration is the area that gives Norway the second lowest score (after trade) in the Commitment to Development Index (CDI). In 2007, Norway scored 4.9 points on the sub-index for migration and was in 11th place on the index. The criticism aimed at Norway is that the increase in the number of unskilled workers to the country since 1990 is small, and that the share of foreign students from developing countries is small. Norway is commended for giving students good economic conditions and for covering large amounts of refugees’ expenses. The CDI gives a higher score to countries for receiving unskilled labour than for qualified labour.

The Policy Coherence Commission finds that for unskilled labour from countries outside the EEA, the opportunities for labour migration to Norway are extremely limited under the current set of rules. The Government has proposed simplifying the rules for recruiting employees from countries both within and outside the EEA area. However, the scheme only applies to well-qualified specialists, key personnel, skilled workers and employees in international companies. The Commission believes that more should be done to facilitate the recruitment of unskilled labour since this can give a positive effect for development in the country of dispatch. Studies show that unskilled workers also send more money home than those well qualified. Any form of migration entails major challenges. It must be a prerequisite that labour migrants, whilst employed in Norway, have the same employment rights as Norwegian workers.

Commission members Audun Lysbakken and Anne K. Grimsrud believe that in the migration policy, the Norwegian authorities must balance various considerations. The immigration of unskilled labour can be positive both for the countries that the migrants originally come from and for Norway. These members take a very positive view of immigration, and is critical to the discrimination of migrants that the EEA agreement imposes on Norway. However, it is vital to prevent increased migration leading to social dumping and the development of a new and ethnic-based lower class in Norway. Unregulated competition for the poorest paid jobs in society is therefore not a positive thing, neither for society nor for people in need of work. A shift in the power balance between employers and employees will have major consequences. Immigration cannot therefore be regulated based on the employers’ wishes alone. This makes it necessary to set restrictions on the opportunity for immigration for unskilled workers. The immigration of unskilled labour must therefore be regulated according to the situation in the labour market, and in a collaboration between the parties in industry and the authorities.

Commission member Kristian Norheim in principle sees free movement of goods, services, capital and people over country borders as a goal. Unfortunately there are several reasons why free immigration is not a responsible policy. One such reason is the generous incentives for staying unemployed offered by the Norwegian welfare state. Opening up for free immigration of unskilled workers that are most needed in low wage positions, and following up by allowing family reunion, within a generous welfare system where demands and duties are not predominant, would make the situation untenable. The potential for integration should also be considered when borders are being opened. The belief that Norway can reduce poverty much by opening its borders for free immigration of both skilled and unskilled labour is naïve. If Norwegian industries are in great need of labour immigration from third countries, one should consider ways and means for employers to take on more of the economic and welfare responsibilities this entails. A Swiss model or a North Sea model should also be considered. Norway can contribute best to poverty reduction in developing countries by supporting political and economic reforms, a freer world trade regime and other measures that could create growth and employment for the poor. This would affect the many and not only the few who are lucky enough to get away.

The Commision notes that since Norway does not systematically register the level of education of immigrants, there is very little accurate information on the level of education of immigrants to Norway, and it is difficult to say whether they represent a brain drain for the country of dispatch. On a global basis, there is currently a substantial lack of qualified health personnel. Recruiting health personnel directly from Africa is restricted, but since Norway imports health personnel from other European countries, and since these in turn can import personnel from developing countries, a domino effect may be in force that is difficult to document. The Commission registers that in the Report to the Storting no. 18 (2007 – 2008) on Labour Migration, the Government highlights the need for national and international rules that prevent key personnel from poor countries being actively recruited to rich countries, and that pending international rules the Government will draw up national guidelines. The Commission supports such an approach.

Many migrants with no official documents live in disgraceful conditions and are exploited by the labour market and housing market, among others. Employers in many countries exploit such labour, which is both cheap, easily replaced and can easily be controlled by threats to make their stay known to the authorities. It is estimated currently to be 5 million labour migrants in Europe with no official documents or legal residence. Irregular migration represents a challenge that needs to be met at various levels. Persons with no official documents do not currently have the right to health services apart from emergency treatment. In practice, this means for example that pregnant women are not entitled to examinations, and that children do not have a right to see the health visitor. The Commission believes it is important to improve the conditions for migrants with no official documents.

The Commission would like to highlight the importance of Norway adopting a human and solidaristic refugee and asylum policy. Norway has a clear moral obligation to take its share of the responsibility for those in need of protection. Asylum seekers that stay in Norwegian reception facilities for a long time often perceive their situation to be depressing and destructive and as poor preparation for integrating in Norway or for a voluntary or forced return. Experiences from Denmark show that language studies, short work preparation courses and work experience placements result in better adaptation both in Denmark and after their return home where relevant.

Norway will have a need for more labour in the coming years, but has untapped labour resources in immigrants that have already arrived in the country. There is a lack of integration and discrimination in the labour market. Not utilising the labour resources in the immigrant population leads to both lost labour achievements for Norway and lost remittances to the immigrants’ country of origin.

Commission member Kristian Norheim does not support the views of the Commission expressed in the previous 4 paragraphs.

Remittances from migrants have a clear positive effect on poverty, and also have a positive connection to other development goals such as children’s education and health. There is currently no legal way to send remittances to Somalia from Norway. Remittances have a clear positive effect on poverty in the recipient countries. Norway has a very restrictive set of rules for remittances compared with other countries. For example, some hawala operators that are legal in the UK, Sweden and Denmark are illegal in Norway. Some of the hawala operators that operate in the irregular market in Norway are publicly registered companies in countries with less restrictive sets of rules. Norway’s stringent regulations for remittances, which lead to little competition among the suppliers, relatively high transfer prices and the total absence of legal remittance alternatives to some countries, are regarded as having a directly negative effect on poverty development. The Commission believes it is important that remittances to developing countries are made simpler and cheaper.

9.4 Proposal for migration policy initiatives

9.4.1 Labour immigration

Initiative 1: With the exception of Anne K. Grimsrud, Audun Lysbakken and Kristian Norheim, the Commission recommends introducing a scheme where unskilled labour from outside the EEA area is treated equally to skilled labour. Anyone who finds work in a Norwegian company should get a work permit regardless of whether they are unskilled or well qualified labour migrants. No restrictions should be set on the volume of labour immigration that requires the relevant party to have an offer of employment in Norway. The obligations that Norway has in relation to the EEA must be met and the regulations must be designed in close collaboration with the parties in industry.

Requirements must be set for conditions of employment and maintenance through own funds. A family of labour immigrants should be able to apply for a residence permit in the family reunification system on a par with the current schemes for skilled labour.

Labour immigrants are given the right to free language studies if they lack basic skills in Norwegian. The Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority should be strengthened in order to ensure that salaries, social rights and other working conditions are on a par with those for employees domiciled in Norway.

Committee members Audun Lysbakken and Anne K. Grimsrud recommend enabling the immigration of unskilled workers from outside the EEA area through quotas that are determined each year in collaboration with the parties in industry and the authorities.

Initiative 2: With the exception of Kristian Norheim, the Commission recommends that Norway tries to a greater extent to comply with developing countries’ proposal for the liberalisation of the movement of labour in the GATS negotiations. Norway should take the initiative to study how labour migrants can be treated more equally regardless of their country of origin.

Initiative 3: Arrangements should be made to stimulate and facilitate those who wish to contribute with their experience and expertise in their native country in different ways. Initiatives that should be considered are:

Loan schemes with greater risk-taking for migrants that wish to start a company in their native country. It should be possible to apply for loans in Norway, with the disbursement of funds taking place in the native country.

9.4.2 Initiatives to limit brain drain

The most effective initiative to combat brain drain is improving job opportunities in the native country. Through measures for strengthening sectors with high volumes of migration such as health and education, it will be possible to help reduce the incentives to emigrate. This will primarily be done through development aid funds and is therefore not covered fully in this report.

Initiative 4: The Commission supports Norway undertaking efforts to ensure that international ethical guidelines are developed for recruiting health personnel and other skilled key workers. Rich countries should not actively recruit skilled key personnel from poor countries. The individual’s right to apply for work in another country should, however, not be restricted.

Initiative 5: The Commission believes it is important that pending international guidelines Norway should devise national guidelines for the responsible recruitment of skilled workers where measures such as restricting the recruitment of qualified personnel, qualifying unqualified personnel in Norway and developing compensation schemes are emphasised.

Commission member Kristian Norheim does not support the views and initiatives 4 and 5 under paragraph 9.4.2.

9.4.3 A simplified set of rules for remittances

Initiative 6: The Commission attaches importance to remittances to developing countries being simpler and cheaper, and the Government actively working towards this. It is also recommended that the set of rules is amended in order to make it possible to transfer money legally to Somalia and northern Iraq. This will also contribute to increased competition between remittance operators.

9.4.4 Irregular migration and refugee policy

Initiative 7: The Commission recommends a more progressive approach in order to improve the conditions for migrants with no official documents both in Norway and internationally. Initiatives that are considered to be important are:

Entitling paperless migrants in Norway to basic health services and legalising humanitarian aid to paperless migrants.

Establishing legalisation schemes for long-term paperless migrants through legislation or regulations. Paperless migrants that have stayed in the country for many years must be given the right to have their cases reassessed, with the emphasis being on actual period of residence. This must especially apply to children. The authorities should consider the use of amnesty for paperless migrants. Amnesties will not be a permanent scheme, not to be speculated in.

Victims of human trafficking that want and need to stay in Norway must be granted a residence permit. Obtaining a residence permit should not be conditional on collaborating with the police. The importance of fighting the people organising human trafficking must not be at the expense of the victims’ rights.

Initiative 8: The Commission recommends that consideration is given to brief job training for asylum seekers as soon as they arrive in Norway. The purpose of this is to facilitate integration and job searching in Norway and to give the asylum seekers job skills that both they and their native country will benefit from upon their voluntary or forced return.

It must be made easier for asylum seekers that are waiting on their residence application being processed to obtain a work permit during the wait.

Commission member Kristian Norheim does not support initiatives 7 and 8.

Footnotes

GCIM (2005) Migration in an interconnected world: New directions for Action, Report of the Global Commission on International Migration, http://www.gcim.org/attachements/gcim-complete-report-2005.pdf

World Bank (2006): Global Economic Prospects. Economic Implications of Remittances and Migration. http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentSer-ver/IW3P/IB/2005/11/14/000112742_20051114174928/Rendered/PDF/343200GEP02006.pdf

Tamas, Kristof (2006): Towards a Migration for Development Strategy. Report commissioned by the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs

OECD (2007), Policy Coherence for Development 2007 – Migration and Developing Countries, http://www.oecd.org/dev

World Health Organisation (2006) World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health