10 Peace, security and defence policy

10.1 Conflict, peace and poverty

Two thirds of Africa’s poor are to be found in countries that have recently experienced or are in the middle of a war or conflict, 1 and 90 per cent of armed conflicts in 2005 took place in low and lower-middle income countries. 2 Armed conflicts lead to major financial losses for the countries and populations that are affected. The African continent alone has incurred a financial loss in excess of NOK 97 billion. Preventing conflicts or reducing the level of conflict is in itself a key contribution to reducing poverty.

While armed conflicts previously led to large military losses, the number killed as a direct result of acts of war is nowadays considerably lower. The civilian population now generally bears the greatest burdens, both during and after violent conflicts, as a direct and indirect result of violent actions. Women are particularly exposed. Violence against women and to a large extent sexually motivated attacks, are used as a weapon in wars and conflicts. Women are rarely present when peace agreements are negotiated, few women take part in civil and military peace operations and women’s human rights are poorly protected in conflict and crisis areas. 3

Successive Norwegian Governments have furthered a policy with emphasis on Norway’s international peace work. This has resulted in a conscious focus on preventing, reducing or resolving conflicts and reducing the vulnerability of exposed groups. This priority is substantiated based on an acknowledgement that security is fundamental to human and state development.

The purpose of such prioritising is twofold. First, there is a wish to save lives, alleviate suffering and secure human dignity. Second, it is important to contribute towards peace and reconciliation due to security policy considerations. One result of globalisation is that conflicts throughout the world to an increasing extent might hold direct consequences for Norway. It can therefore be argued that initiatives to further peace and reconciliation in distanct countries can contribute to stability, security and the protection of Norwegian interests. However, such initiatives might place the interests of Norway and Norway’s allies’ in conflict with considerations towards development, stability and security in other countries. This makes it necessary to constantly measure the coherence in Norway’s international engagement, to determine the interests it is motivated by, and identify which potential conflicts of interest that must be weighed up against each other.

Norway has a long tradition of contributing to international military and civil operations in areas hit by war and conflict, with military forces since 1947 and with personell from the police and justice sector since 1989.

Norway is also a significant humanitarian contributor, and a number of our relief and development projects are carried out in countries that in different ways are exposed to armed conflict and instability. Norway and Norwegian organisations have assumed key roles as negotiators and facilitators of different peace initiatives, including in the Middle East, Colombia and Sri Lanka. The statistics of international and Norwegian development aid in chapter 3 illustrates the extent to which development assistance and emergency relief have become a political instrument, and how countries where Norway is involvement in peace processes and international military operations are prioritised financially.

Norway’s participation in international military operations and various peace initiatives has generally been founded on a clear political majority in the Storting. The overarching Norwegian security and defence policy goals are set, but the content of the policy might change as framework conditions, challenges and the security threat profile change. Three factors are particularly important;

Legitimacy (political and moral) and legality linked to participation in international military operations.

Cooperation and collaboration between civilian and military actors in international military operations.

Measurement of results of our peace initiatives.

Point number two is particularly important for emphasising the planning and execution of multidimensional and integrated missions.

The main question in this chapter is therefore whether it can be documented that Norwegian civil and military efforts internationally have contributed to poverty reduction or at least not undermining the poverty reduction goal. The second most important question is whether there can be any conflict of interest between respectively Norwegian security policy and development policy considerations.

Within this broad policy area, the Commission has chosen to focus on coherence challenges regarding harmonisation within peace and reconciliation work, arms and arms exports and our international military missions. These areas provide and opportunity to discuss some central areas with possibly conflicting interests given Norway’s prominent international peace role, the fact that Norway is the world’s largest arms exporter in relation to number of population, as well as the Norwegian emphasis on strengthening the UN’s military peacekeeping role while contributing limited number of Norwegian armed forces to these. There are other areas with major conflicts of interests but the Commission has chosen to focus our suggested initiatives towards the aforementioned topics.

10.2 A UN-led global order

People’s ability to live in safety is fundamental to peace and freedom. Out of the six threat categories the UN’s High-Level Panel in 2004 called upon the world to show concern for in the coming decades are five security-related: war, violence, attacks, the nuclear threat, terrorism and organised violence. 4 Armed conflicts lead to human suffering, inhibit development and results in major financial losses for the affected countries and populations. Establishment of peace or reduction of the conflict level can thus be a key factor in reducing poverty.

In 2007, 13 major conflicts were registered in 13 areas, where Africa and Asia dominate. 5 According to some estimates, two thirds of Africa’s population live in countries that recently have been trough or still are in a state of civil war. Democratic societies are least vulnerable to internal and armed conflicts, although not necessarily renouncing the use of military force in other countries. Autocracies suppress regime criticism and revolts, and have therefore few armed conflicts. By contrast, anocracies, which are neither fully democratic nor fully authoritarian, have the majority of armed conflicts. Africa south of the Sahara, the Middle East and central and southern Africa have a high share of anocracies.

The optimism following the end of the cold war as for the the UN Security Council’s ability to intervene in conflicts was short lived. We are witnessing the development of a multipolar world that can potentially impair the UN’s efficiency to intervene in conflicts or make the mandates for UN interventions less robust. Growing differences at a global level, increased competition for natural and energy resources, a possible resumption of nuclear arms-related programmes, the spreading of technology and material to product weapons of mass destruction and a greater degree of privatisation of security in conflicts are all examples of conditions that impair the UN’s role in conflict prevention and management.

Despite this development, the UN is in a unique position to facilitate peace, development and security on behalf of the global community. Norway is a significant financial contributor to the UN, and was the 6th and 7th largest contributor in 2006 and 2007 respectively.

International collaboration is a prerequisite for peaceful international development, and not least for a necessary strengthening of international law. Norway has sought to anchor its international engagement through an active membership role in international organisations, and by maintaining a broad international engagement to influence development of both policy and practice within the peace and security sector.

Regional organisations such as the African Union (AU) hold a major potential with regard to regional crisis handling. NATO remains a cornerstone in Norwegian foreign, security and defence policies. The development of a common European security and defence policy (ESDP) influences the priorities made in Norwegian security policy and on European military collaboration.

Figure 10.1 Map of armed conflicts in 2006

Source The International Peace Research Institute, Oslo, PRIO, Centre for the Study of Civil War, CSCW. Press release dated 10.9.07 «The world is better than its reputation».

There is in addition an extensive collaboration between «like-minded countries», researchers and non-governmental organisations. This form of networking is time-consuming and resource-intensive, but the process leading to the prohibition of the use of landmines and cluster ammunition is an example of the significance and influence of non-governmental cooperation.

10.2.1 Security policy development features

A number of factors characterise the development of the security policy framework, including a strengthened position for Russia and China as well as regional actors. The USA remain the dominating military power, but shows signs of a weakened economic position.

The ending of the cold war changed the international conflict profile. The main tendency is a change from war between states to an increasing number of internal conflicts, a mainly peaceful Europe while the majority of conflicts are localised in Asia and Africa. The use of terror as a method is a feature of the current conflict profile. Such a use is nothing new, but protection against terrorism is central to in many countries’ security policy since the terrorist attacks in the USA and European countries at the start of this decade. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the growing tension in the Middle East, are in the same way pivotal in the international security policy picture. The USA’s invasion of Iraq has led to a diminished international confidence in a multilateral approach to security.

The increasing demand for energy sources and the shortage of natural resources constitute a potential source of conflict. Secure energy accessibility, primarily petroleum and gas, are important for all countries and the significance of energy security will increase in the years to come. This includes securing infrastructure connected to energy production and delivery.

Another factor that increasingly affects security, stability and conflict risk is the climate changes. Those living in the largest poverty, in underdeveloped or unstable states with undemocratic and corrupt Governments are in principle the hardest hit. 6 A strong correlation has also been demonstrated between political stability and a country’s ability to prevent ecological disasters or damage. 7

10.2.2 Norwegian security policy

One of the fundamental aims of Norwegian security policy is to protect Norwegian interests through securing Norwegian territorial integrity, sovereignty and political freedom to manoeuvre. The extended security concept includes diplomatic, economic, social, political and environmental instruments. The defence policy is the part of the security policy that deals with the use of military instruments.

The overarching goals for Norwegian security policy are: 8

To prevent war and the development of various threats to Norwegian and the collective security;

To contribute to peace, stability and the further development of a UN-led international legal system;

To protect Norwegian sovereignty, Norwegian rights and interests and protect Norwegian freedom to manoeuvre with regard to political, military and other pressure;

To defend Norway and NATO from strikes and attacks, together with our allies;

To protect society from strikes and attacks from governmental and non-government actors

The linkage between the security policy and the defence policy is formulated in the defence policy goals. The goal most relevant to highlight here is that, within its area of responsibility and through collaborations with other countries’ authorities where appropriate, the Norwegian Armed Forces shall:

Together with our allies, through participation in multinational peace operations and international defence collaborations, contribute to peace, stability, enforcement of international law and respect for human rights, and guard against the use of power by governmental and non-government actors against Norway and NATO.

The global challenges and threats are more diffusive than previously, and are characterised by sliding transitions between the national and the international, and between peace, crisis, armed conflict and war. The risk assessment therefore dictates that Norwegian security is best protected by contributing to peace, stability and a favourable international development, and in this way reduce the risk of crises, spread of conflict, armed conflict and war.

10.2.3 Human security

The extended security concept entails a far broader approach to security, and an understanding that military instruments alone cannot create lasting peace and stability.

As already discussed, many of today’s conflicts are intrastate and the acts of violence are often carried out by different types of armed groups, and affects in particular civilians. In recent years, we have witnessed in a number of the world’s conflict zones military strategies based on the use of air bombardment and cluster ammunition by some states, while improvised explosive devices are used by their adversaries. A growing number of civilians are being killed by organised groups in urban areas, often caused by states lacking ability to provide security for their citizens. 9 No statistics show the vulnerability towards being killed in a war or conflict in relation to gender or age, despite the UN Security Council’s resolution 1325. This resolution aims to increase women’s participation in conflict resolution and in efforts aimed at securing lasting peace, and to strengthen protection of women’s rights in conflict areas. Norway has developed a «Plan of action for women’s rights and equality in the development work, 2007–2009». 10

Two UN initiatives are pivotal to the efforts aimed at improving the human security; «Human Security» and «Responsibility to Protect». Fundamental to the reasoning is that the international community must take responsibility for protecting civilians from mass murder, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and injustices against humanity, in cases where the national state has failed its responsibility. Both concepts are based on the security’s indivisibility. Everyone has a right to security without differentiating between degrees of vulnerability.

Human security means protecting people from critical and continuous threats and situations, by building on their strengths and aspirations. This included establishing systems that provide people a basis for survival, dignity and subsistence.

Human security complements state security, facilitates human development and strengthens human rights. It complements state security by being human-centred and addresses insecurity that has not been considered a threat to states.

Responsibility to protect (R2P) populations from mass murder, ethnic cleansing, war crimes and crimes against humanity are international governmental obligations aimed at preventing and reacting to serious crises, regardless of where they occur. In 2005, agreement was reached within a UN framework that states have the main responsibility for protecting their own population while the international community has a responsibility for initiating initiatives when these Governments do not make efforts to protect those most vulnerable.

The concepts have been attacked from two sides. On the one hand, questions have been raised concerning whether the concepts have been too watered down to be relevant and to prevent major injustices. 11 On the other hand, other quarters have expressed concern that these concepts might provide the UN Security Council and its members with a too extensive power in overruling states’ sovereignty. Nevertheless, the concepts are generally accepted and incorporated into Norway’s goals for securing the life of individual human beings.

Considerations of the Commission

The Commission with the exception of Kristian Norheim find that the UN is the world’s most important organisation for preventing and reducing conflicts.

Norway should in particular support the UN’s reform efforts with a view to making the organisation more effective and improving the utilisation of its resources. It is important for the legitimacy of the UN that the organisation is perceived as an organisation for all countries. Within the security field, it is particularly important to support the efforts aimed at improving command, control and management structure to enable the UN to lead complex international operations. In relation to peace and reconciliation, further development of the Peace-Building Commission is a crucial focus area.

Figure 10.2 The United Nations plays an important part in co-ordinating interaction between countries.

In order to ensure a more secure economy for the UN, the Commission with the exception of Kristian Norheim is of the opinion that Norway must contribute to arrangements that ensure that the member countries meet their economic obligations towards the organisation. At the same time, Norway must work towards the UN building up own sources of income.

As a small country, Norway has a particular need for international rules that prevent arbitrary use of power and which protect the interests of weak nations and weak parties in the global community. Norway must therefore aim to develop and secure such rules.

Norwegian foreign policy must defend and further develop rights for states and individuals as laid down in the UN pact, the Geneva Convention and the Declaration on Human Rights.

The Commission with the exception of Kristian Norheim is of the opinion that it is through the UN that the world can start to move towards a collective security system, which to a large degree can be governed by the consideration to development, human rights and stability, and to a lesser extent by individual countries’ strategic interests. The Commission majority is therefore of the opinion that in the distribution of Norway’s scarce military resources, Norway needs to strengthen UN’s capacity by prioritising resources to UN-led operations.

Commission member Julie Christiansen is of the opinion that it would not be natural in the security area to detach the use of Norwegian military forces abroad from Norwegian security interests. This implies that in today’s situation it is difficult to have as a base for all decisions that UN led operations should have priority. There is not necessarily any contradiction between UN’s role as a legitimizing body and participation in NATO and EU led operations.

10.3 Norwegian peace and reconciliation work

Situations can arise in which military presence is required to protect human security and help terminate conflicts that lead to serious breaches of human rights, suffering for the civilian population and damage to human livelihood. However, there is no doubt that preventing conflicts and resolving conflicts through negotiation saves both human suffering and economic resources compared with to the use of military resources. Peaceful conflict resolution will normally lay a better foundation for development and poverty reduction following a conflict, and an important initiative for ensuring a lasting peaceful solution is the implementation of a security sector reform. 12

10.3.1 Norwegian support to peace processes

Norwegian authorities, Norwegian non-governmental organisations and research institutions have for a number of years played an active role in various peace processes. Norwegian authorities provide considerable support to international organisations that work for peace, conflict resolution and reconciliation. A positive development in this respect is that more wars are now terminated through negotiation than through a military victory, however there is a relapse to armed conflict for 43 per cent of these negotiated settlements. This particularly applies where there are unsettled disputes over land and where the peace process did not have the necessary support or was poorly framed. It has also been demonstrated that only 50 per cent of the agreements included proposals for weapons control. 13

Use of development assistance to build peace after a conflict is a priority of the Norwegian authorities. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has established a separate section with responsibility for peace and reconciliation efforts. The strategic framework for peace-building was presented in 2004, and in 2008 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs established the Norwegian Peacebuilding Centre. This resource centre is to help develop expertise for the UN’s Peace-Building Commission, Norwegian authorities and other parties involved in this field.

An important perspective here is that conflict resolution can lay a development foundation through national policy processes, among other things, being initiated through the strengthening of the constitutional state. Instruments that Norway can contribute with in the latter field are police forces, judicial experts, court and prison personnel and more general democratisation and election support. Another area in which Norway has made its mark internationally is through the support for the ban on weapons with unacceptable humanitarian and development-related consequences, and which to a large degree targets the civilian population. This includes antipersonnel mines and cluster ammunition, where the agreement entered into in Dublin in May 2008 received support from more than 100 countries.

Among the circumstances that makes Norway a credible third party in conflict resolution processes, is the tradition as a significant financial contributor, absence of a colonial history, extensive NGOs and missionary networks, quick and flexible finance instruments, and cross party support on Norwegian initiatives that enable Norwegian players to withstand setbacks in peace processes. However, Norway does not function in a political vacuum and international resolutions, such as terror listing, can limit the scope for Norway’s negotiation role. 14

No individual country holds a particularly high share of successful peace mediation efforts when they act alone. In almost all conflicts, Norway works closely with other countries, and particularly with the superpowers and regional or other international organisations. During investigative phases, where the parties require discretion, they may prefer organisations or small states as facilitators.

The process of building a lasting peace begins when the parties have reached an agreement, and this requires a long-term effort from many actors. The UN and weighty peace nations are committed to creating coalitions, groups of friends and other measures to coordinate the international support for the parties’ conflict resolution. The UN or selected countries often have special tasks in the coordination of the effort. In recent years, new actors have emerged on the scene holding different traditions and policies for conflict resolution, which can lead to conflicting interests among countries wishing to contribute.

Textbox 10.1 Norwegian involvement in peace processes

Norway was active in 13 peace processes in 2007

Norway makes a contribution to most of the world’s peace processes

Norway was the facilitator in the peace processes in the Philippines and Sri Lanka

Norway plays a more or less active role in 11 other conflict areas: Haiti, Somalia, Colombia, Nepal, Afghanistan, Sudan, Uganda, East Timor, Ethiopia/Eritrea and Burundi

The total frame for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ contribution to peace and reconciliation work, human rights, democracy and humanitarian aid is estimated at NOK 4.4 billion for 2008, or 20 per cent of the total development budget.

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs

10.3.2 Security sector reform

Another area Norway has prioritised through international organisations and own priorities is security sector reform (SSR). This based on the recognition of the need to protect individuals and society in an increasing number of internal conflicts, and, moreover, to ensure that national security enforcement does not threaten democracy, human rights or development, and is neither used by undemocratic Governments in order to retain their power.

The UN Security Council stated in 2007 that SSR is critical for consolidating peace and stability, for facilitating the reduction of poverty, improving legal systems and effective governance, and extending legitimate Government authority and preventing states relapsing into conflict. As the British DfID states «…a poorly handled security sector hinders development, reduces investments and helps poverty to continue.»

According to the OECD/DAC, a reform of this nature is a remodelling of the security system that includes all actors, their roles, responsibilities and actions, whereby it is led and driven in a way that is more in-keeping with democratic norms and good governing principles, and as such contributes to a well-functioning security framework.

This results in a far broader organisational security approach. In addition to the traditional security players, such as the armed forces and police, it also includes overarching governing and legislative bodies, the civil society’s organisations, justice and legal system institutions, such as courts and prisons, and non-government security actors. 15

One of the challenges related to poverty reduction is that an SSR in itself does not necessarily contribute to the reduction of poverty, perhaps especially where military and other security and intelligence players are intertwined in states’ economic, social and political system, or where the Government is dependent on the military for retaining the power. In such cases, careful consideration must be given to whether an SSR should be supported, and if so it must be as part of a more long-term and poverty-reducing strategy.

According to the OECD, a coherence challenge is a lack of a holistic SSR strategy, which leads to donors supporting individual components instead of ensuring the totality of the programmes. A shortage of expertise to assist the countries has also been reported, not only in a technical sense but in creating an understanding for the need for reform, strengthening the organisation and local ownership.

Considerations of the Commission

The Commission believes that peaceful prevention and resolution of conflicts is the instrument that has the greatest effect for development and poverty reduction. Norway must continue and strengthen the effort to contribute to peaceful solutions to conflicts, and to the reconstruction of states and communities that can eventually be in a position to handle their own conflicts using peaceful means and protecting the interests of the most vulnerable.

At the same time, there must be a recognition of the need for collaboration and interaction with a broad range of states, organisations and individuals in order to ensure that these processes result in lasting and development-inducing solutions. This requires a high degree of professionalism and careful consideration of instruments and type of involvement on the Norwegian side. A greater degree of focus on women’s involvement in peace processes will help strengthen this work.

Furthermore, the consistency of the various initiatives must be taken into consideration as Norway to such a large extent prioritises support to reconstruction, aid and state building for countries in which Norway has played a part in securing a peace solution. One prerequisite for Norway’s ability to make a positive contribution to such processes is the possession of basic knowledge on countries and conflicts, as well as an ongoing debate on the content and outcome of Norwegian peace involvement.

In many countries in war and conflict, children and young people often constitute a large part of the population. This requires that the younger generation is included as key players in the processes that are to lead to a sustainable solution to the conflict, both in the actual peace process and in the reconstruction phase.

Norway and Norwegian organisations and researchers, have been driving forces in the effort to ban antipersonnel mines and cluster ammunition, and in limiting the spread of hand weapons. This is an initiative that is extremely important to continue as it has a great potential to reduce the threat to poor and vulnerable groups. Another important arena is the security sector reform. Here it is important to ensure democratic control over military instruments of power following a conflict, and to ensure that these instruments are not used against the population or to maintain oppressive regimes.

10.4 Arms and the arms trade

Access to weapons and ammunition is a prerequisite for the ability of a military force to maintain security, but these are also used to oppress and impoverish groups and individuals. Being able to limit the access to weapons and ammunition can therefore be an extremely important instrument for improved security and development. On an international level, this applies to hindering the proliferation of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons of mass destruction, which can threaten large parts of the world population. On a local level, it applies to hindering access to hand weapons and ammunition for groups and individuals that constitute a threat to peace and security. Some of these efforts must take place within international organisations, but Norway is also in a unique position to directly affect the control of the proliferation of weapons and ammunition.

Norwegian industry, including part government-owned companies, is a main supplier of weapon systems, components for the arms industry and ammunition. Norway is ranked as number 20 on the list of trade with Major Conventional Weapons (MCW) for 2006. 16 The Norwegian Government owns 50 per cent of the Nammo group, which in 2003 was the world’s third largest producer of ammunition, and also has factories in Sweden, Finland and Germany. Report to the Storting no. 33 set the total value of Norwegian weapon exports in 2006 to NOK 2.92 billion, of which 15 per cent was ammunition and explosives, and a continuous increase in exports has been noted in recent years, particularly for ammunition. The bulk of these weapons and the ammunition were exported to other NATO members and the Nordic countries, but also to Japan, Switzerland and Australia.

A Storting resolution from 1959 says that «Norway will not permit the sale of weapons or ammunition to areas that are at war, or where there is a threat of war, or to countries involved in a civil war». 17 A 1997 clarification says that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs shall further consider «aspects linked to democratic rights and fundamental human rights». Norway operates an A and B list for types of weapon for export, where A is subject to the most stringent control. Likewise, the types of countries that export licences can be granted to are divided into three. Group 1 consists of NATO members and other related parties, group 2 is countries that Norway will not export defence material to, and group 3 is countries than can receive material from the B list. This control system is more stringent than that followed by many other NATO countries and Norway has also affiliated itself with the EU’s «Code of Conduct on Arms Export». At the same time, it has been registered that Nammo’s factories outside Norway do not adhere to Norwegian export regulations. This results in sales to countries that Norway considers to be undesirable recipients of hand weapon ammunition.

The challenge, in a security and poverty perspective, is not therefore primarily the control imposed on weapon exports from Norway, but that the buyer countries can re-export the Norwegian-produced military material – including NATO countries. In order to prevent arms going to undesirable recipients or to limit the recipients’ use, an end user certificate (EUC) has been introduced where Norway shall give its consent to re-exporting from countries that signed this. However, group 1 countries, including NATO allies, are exempt from the certificate scheme.

Considerations of the Commission

The Commission is of the opinion that Norway has a great opportunity to help reduce the vulnerability of the civilian population in conflict-hit areas, both through its own initiatives, developing agreements in international organisations and via contributions to disarmament and security sector reform in conflict areas.

Arms and ammunition production can lead to more violence towards the poor and vulnerable, and arms and ammunition can be tools for oppression by states, groups and individuals. It is important for Norway as an arms exporter to introduce measures that lead to transparency and which provide the opportunity to trace exported weapons and ammunition.

Norway must take active part in the international effort related to the proliferation of nuclear weapons and for the nuclear powers to abide by the disarmament obligations of the Non-Proliferation Treaty. And, moreover, that the conventions on chemical and biological weapons of mass destruction are followed up and sharpened. We must make an active contribution to the strongest pressure possible on states that might possess such weapons.

10.5 International operations

The threshold for the use of military power has, as far as Norway is concerned, always been high. In accordance with the UN pact and the NATO treaty, Norway has an obligation to contribute to international military operations in certain cases. As per article V of the NATO treaty, Norway has an obligation to assist if a NATO country is subject to an armed attack. This NATO obligation is also founded in article 51 of the UN pact, which provides for a state’s right to military self-defence against armed attacks. If the UN Security Council gives a mandate for the use of armed power pursuant to chapter VII of the UN pact, Norway as a member state is obliged to support the resolution, even although this does not entail an automatic obligation in international law to provide a military force contribution.

10.5.1 Norwegian participation

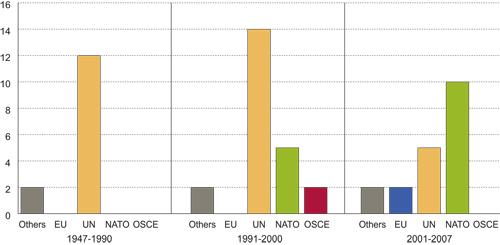

From participation in the Independent Norwegian Brigade Group in Germany in 1947 to the current engagement in Afghanistan, Norway has provided almost 120,000 personnel in 56 different operations. 18 The majority of these operations have been carried out under direct UN leadership or a UN mandate, where either NATO, the EU, AU or coalitions have been responsible for the exercise. Participation in these operations has formed part of Norway’s overall foreign and security policy. Simultaneous to the number of peacekeeping operations rising from 1990, according to information from the Norwegian Military Forces there has been a clear reduction in the Norwegian participation in UN-led operations to the benefit of operations under NATO command, and Norway has also been involved in EU-led operations. Out of the ten states that take part mostly with uniformed UN forces, seven are low-income states, with Bangladesh, Pakistan and India being the three largest contributors of troops. Early in 2008, the UN had 82,000 military forces and 9,000 police outstationed. Norway took part in six of these UN operations, but provided only 56 military personnel and 38 police officers.

Norwegian police have taken part in international peace operations since 1989, known as the «Civilian Police». This has mainly been under UN leadership and includes the training of national police, but Norway has also contributed to regional organisations and in bilateral projects, with 30 officers being dispatched in 2007. An effort to improve women’s security is part of the mandate. The Government’s goal is that up to 1 per cent of the Norwegian police force at any time shall take part in peacekeeping missions.

The Ministry of Justice and the Police set up the Norwegian Crisis Response Pool as an emergency action group in 2004, with the UN, OSCE and EU as central commissioning parties. The group consists of 40 members, including judges, public prosecutors, judge advocates, police lawyers and personnel with prison work experience. The aim is to provide advice and assist towards development of democracy and constitutional states in countries that have been subject to war, internal conflicts or are undergoing democratisation.

Figure 10.3 Norwegian participation in international peace operations. 1947 – 2007

Source Data received from the Norwegian Defence

10.5.2 Legality and legitimacy

Over the past 10 years, three international conflicts in particular have initiated a discussion on the legality and legitimacy of military operations:

Kosovo 1999: There is disagreement regarding the legal basis for NATO’s military action. There was no UN Security Council madate for the operation but those who argue in supported of NATO’s attack on Yugoslavia are of the opinion that the military intervention was justified on humanitarian grounds and thus in accordance with international law.

Afghanistan 2001: Both the USA’s invasion and NATO’s subsequent engagement in Afghanistan have been carried out in collusion with the UN Security Council, and with a mandate from the UN.

Iraq from 2003: There is broad agreement that the American attack on Iraq was not in accordance with international law. Only after the invasion did the UN Security Council pass resolutions that welcome the presence of international forces.

In all of these cases, there has been debate in Norway and other western countries on whether military intervention could be supported. It has been shown that legality and legitimacy are not necessarily connected. Legal military interventions can be perceived as illegitimate, and illegal ones as legitimate.

The discussion on whether there is a basis in international law for humanitarian intervention is almost as old as the international law. Since the UN pact, Norway’s view has been that there is no right to humanitarian intervention beyond the international law. This is because the UN pact does not only govern what types of threats should be dealt with using international military initiatives, but also establishes procedures for how resolutions on military initiatives shall be carried out: The UN Security Council has the monopoly on providing the mandate for international force beyond the self-defence cases.

10.5.3 Operation types and complexity

Since World War II, Norwegian forces have taken part in operations over the full conflict scale:

Conflict-preventing operations

Military observer missions

Peacekeeping operations

Peace-establishing operations

Humanitarian operations

An international military operation will normally go through four phases after a demanding preparatory phase; 1) Entry, 2) Execution of the operation, 3) Stabilising, 4) Military security for reconstruction. The civil and military instruments will vary in scope and intensity depending on what phases are undergone, and there will be a constant assessment of what type of instrument is needed in the relevant context, and how they should be phased in and out.

With the exception of Iraq, there has been a tradition of a consensus in Norway regarding participation in military operations, with opposition from only single political parties. However, there is growing debate regarding Norwegian participation in international military operations, and what type of missions Norway should take part in.

In integrated, multidimensional missions the UN coordinates military, humanitarian and development-oriented efforts. This includes facilitating humanitarian aid and economic reconstruction, demobilisation and reintegration of former soldiers, reconstruction and reform of the police and judicial system, supervision to ensure respect for human rights and that elections are held 19.

The previously discussed complexity in today’s conflicts puts stringent requirements on political authorities, military forces and civilian actors. It is an international political responsibility to analyse and address the reasons for conflict, and simultaneously contribute to negotiation-based solutions and protection of a population under threat. It is also a political responsibility to furnish and prepare the actors that will take part in an operation in a way that makes it realistic to carry out the mission, from a military, civilian and humanitarian perspective.

The operations’ complexity also places extremely high requirements on military forces with regard to practice, training and equipment, robustness in relation to rules of engagement and the capability for interaction with and understanding for other actors’ mandates, ways of organising and setting priorities.

Politicising, increased complexity and more operational experience have led to an intensified focus on integrated missions, 20 and the multidimensional challenges these entail. There is an ongoing debate on the relationship between civil and military actors in the operation area. Focus is aimed at the need to improve coordination and interaction, clarify roles and improve knowledge of each others’ activities and modus operandi. This applies to all levels, from overarching international political coordination to local cooperation in the field.

10.5.4 Coordination and organisation

Civilian actors that operates in conflict areas constitute a conglomerate of multinational, international and national humanitarian and development-oriented organisations and includes both governmental and private ones. Whilst on the political, military and civilian side there are a number of coordinating bodies, creating a coordinated effort is a challenge, as is gaining acceptance that coordination will lead to organised interaction and not control of individual actors. In addition to the nation state, civilian actors make up the most important component in state building, recovery of the constitutional state and in reconstruction and provision of humanitarian assistance, and there is growing recognition that ensuring lasting peace primarily depends on this effort.

All of Government approach builds on the acknowledgement that vulnerable states can constitute both a development challenge and a threat to international security, and the security, governance and development challenges must be viewed in context. This entails that Governments that involve themselves in such conflicts must ensure an integration of their defence, diplomatic, development and other policy instruments with regard to these states.

A part of this debate is to what extent military personnel shall take part in humanitarian, reconstruction and state building activities, and under whose command. The existing framework for assistance provision in complex crises places the military organisation, assistance prioritisation and provision under a humanitarian command, outlined in the Oslo declaration. 21 The introduction of Provincial Reconstruction Teams, with both military and civilian personnel, has challenged this division. There are major differences here between nations with regard to what degree the military is responsible for provision of humanitarian assistance and implementation of rehabilitation and development projects, or whether they leave this to the humanitarian actors or private companies. Norway has maintained a clear division in these tasks, but this is the subject of ongoing international debate.

According to NATO’s doctrine, 22 the Civilian Military Co-operation (CIMIC) is defined as: «Coordination and collaboration, to support the mission, between a leader of the NATO operation and civilian parties, including the national population and local authorities, as well as international, national and non-government organisations and agencies.» CIMIC has three main functions; 1) civilian-military liaison to facilitate and support the planning and execution of the operation, 2) support for the civilian environment in order to underpin the military operation and 3) support for the military force in order to ensure civilian support and information.

This in turn places great demands on contributors. On this basis, it is also interesting to analyse how we in Norway choose to organise ourselves to meet these challenges. The Afghanistan mission gives an insight into organisations and the civilian and military division. With regard to 2008, there is a parity between the financial contributions towards the military and civilian effort, and Norway has a strong involvement in improving the UN’s coordination role. The Norwegian military forces are placed under ISAF command, and Norway heads a Provincial Reconstruction Team in the Faryab province in addition to Norwegian special forces being stationed in Kabul. There are also Norwegian military personnel in ISAF headquarters and in UNAMA.

NATO’S Comprehensive Approach aims to execute military, political, development and humanitarian policy instruments in a holistic and coordinated manner 23.

The Faryab province has moreover a presence of police and personnel from the Norwegian Crisis Response Pool, while Ministry of Foreign Affairs staff administer the humanitarian/development support. A clear division is thus created between the military and the humanitarian operation, while there is an opportunity for a close and coordinated collaboration. Norway also provides personnel from the police and the Norwegian Crisis Response Pool to central Government bodies in Kabul.

A central coordination group for Afghanistan has been established in Norway, in which ministries involved are invited to secure contact at both a political and civil service level. Based on an assessment of this organisational arrangement, the Policy Coherence Commission is of the impression that this does not to a sufficient degree safeguard a coherent Norwegian policy for international operations.

Considerations of the Commission

The Policy Coherence Commission with the exception of Kristian Norheim is of the opinion that the threshold for the use of military powers should be high. Norway’s participation in international military operations requires a clear UN mandate, the forces need to be equipped, trained and prepared in a way that makes them able to resolve the various challenges that the mission entails, and the delineation of boundaries between our civilian and military contributions must be clear. Norway should also take an active part in building capacity and increasing expertise in regional organisations.

The Commission is moreover of the opinion that being able to think and plan holistically in all phases of the operation is a determining factor for the success of an operation. This to ensure the greatest possible degree of coherence, transparency and understanding during the decision making processes between the affected parties. It is fundamental to a holistic approach that the many actors that operate in the core and outer edge of various operations have thorough knowledge of and respect for each others’ expertise, fields and methods of operation. The Commission therefore suggests a number of measures to improve this knowledge.

Multidimensional and integrated missions are characterised by great complexity. It is vital for a successful execution that we are able to coordinate national contributions in the most effective and systematic way possible and that the way we choose to organise ourselves takes into account the diversity of players and multidiscipline involved in the decision processes.

Commission members Julie Christiansen and Kristian Norheim are of the opinion that although a lower level of conflict will generally strengthen Norwegian security, the use of Norwegian forces abroad must always be based on a thorough security policy assessment. These members also believe that contributing to a UN-led world order is an important vision, but as the UN’s expertise, capacity and organisation stands today, other security organisations will be important in the exercising of international military operations. There is not necessarily any contradiction between supporting the UN’s legitimising role and to help strengthen other defence collaborations and security structures internationally.

In building the Norwegian Armed Forces, Norway should factor in support for and participation in UN-led operations.

10.6 Organisation and resources

There are many and diverse actors involved in the peace, security and defence sector. With an increasing focus on the development of integrated and multidimensional missions within the UN, a «comprehensive approach» within NATO and a greater degree of civilian-military interaction in the field, this places new requirements for a coordinated policy development, practical interaction and not least ways of organising the efforts. In brief, a more holistic approach combined with a clear role distribution. Interaction takes place between Government and private institutions and organisations with very different mandates, organisational structures and traditions, that traditionally have had limited formal contact and experience in collaboration.

Experience dictates that a detailed control of actors involved would not succeed; it can rather hamper the utilisation of the breadth of knowledge, involvement and networks of the various actors. Multidimensional approaches place even greater requirements on the form of organisation and interaction, and on space for critical discussions on approaches and priorities. At the same time, there appears to be broad agreement that the current way of organising is not adequate to ensure a more coordinated effort; it is too fragmented in relation to knowledge and organisation.

The report « A strengthened defence» (NOU 2007: 15) points out the need to improve the coordination of Norwegian military and civilian efforts in international operations, and in the present report’s poverty perspective the Norwegian peace effort, security sector reform involvement and weapon export must also be included. This entails policy coordination and involvement of all sector ministries in decision-making processes, and a broad and permanent organised consultation to ensure that a broad range of opinions as possible are brought into the debate when balancing Norwegian obligations and interests, and in ensuring the broadest support possible for the chosen policy.

Considerations of the Commission

The Commission is of the opinion that organisational structure and clarified responsibility are two key factors for succeeding in finding the best policy instruments for ensuring peace and development in a given situation and phase of a conflict. This applies in Norway, in international organisations, in relation to states in and after conflicts with those who carry out the practical peace, reconciliation and reconstruction and development work in the field.

If Norway is to succeed in its peace initiatives and international operations, professionalism must be exercised in all areas. This entails the Norwegian actors holding the necessary expertise and resources to fulfill the responsibilities they take on, and that this become part of a continuous process of reflection and learning. This requires shared skills-building and establishment of a permanent centre of competence.

Stronger er emphasis on expertise can entail a need to prioritise the Norwegian effort, both between actors and priority areas. When then considering where Norwegian resources should be targeted, its ability to reduce poverty must weight heavily in.

10.7 Overarching considerations of the Commission

The Commission is of the opinion there is an obvious correlation between conflict and poverty. Policy instruments that can create peace and improve security for the poor might at the same time facilitate economic and social development and can contribute to the development of more efficient governance. This is in turn positive for Norway, for securing Norwegian interests and for the global community. Peace is a common good when it also protects the interests of the poor and helps in establishing good governance.

Creating and maintaining peace or reducing the level of conflict, either through negotiations, civil contributions or by employing military forces in conflict-preventing, peace-inducing and peace-keeping operations can create the prerequisites needed for poverty reduction.

Peace, defence and security policy is an area with many coherence considerations. The principal consideration is the harmonisation of Norwegian policy and choice of the policy instruments that are most effective in relation to poverty reduction and guaranteeing sustainable development. Another consideration is what policy instrument should be used in what situation, taking into account our obligations towards the Millennium Development Goals, human security, R2P and obligations towards alliances we are members off. And, moreover, when are the different initiatives to be phased in and out, and how best to protect and balance the interests of those in need of peace up against protection of the Norwegian civil and military forces that are to assist them? Additionally, what provides the best result in relation to poverty reduction in both the short and long term, and what is the most cost-effective use of Norwegian and international resources?

The simple answer is that initiatives that can prevent or resolve violent conflicts through negotiation or by peaceful means provide the best return for the world’s poor. This remains a valid conclusion despite the fact that many negotiated conflicts relapse into a new conflict after the first negotiated settlement. A combination of political and humanitarian/ development-related instruments will have to be used throughout the entire process from prevention, via negotiation to reconciliation and the establishment of a (more) peaceful co-existence. Negotiations and peaceful solutions form the basis for greater participation from poor countries and increases their ability to handle own conflicts, and thereby a higher degree of local ownership and responsibility for ensuring and preserving peace, good governance and development.

One overarching goal is to limit damage to the civilian population and reduce the use of violence. Export control and the tracing of ammunition, control of hand weapons, strict enforcement of the ban on landmines and cluster weapons and security sector reform are policy instruments that have extensive international support, for which Norway is part of an international network and is in a position to influence policy. This is an area with extensive interaction between political, civil society and military actors, with broad participation from developing countries that might generate international networks to further such policies internationally and in the poorest countries.

In some cases the use of military means will be the only viable alternative for protecting populations, preventing attacks against the most vulnerable and damage to infrastructure and property. Conditions that increase poverty and vulnerability, and hinder development. Military interventions are the most resource-intensive with regard to personnel, logistics and funding. Experience has led to an increasing recognition that the military interventions must be combined with political and development-related instruments in order to contribute to lasting conflict reduction. Military interventions are highly politically sensitive and places a high demand on organisational capacity and coordination in Norway and internationally.

Given the complexity and the large number of different actors, in Norway and internationally, and the need to prioritise different instruments during the different phases of an intervention, there is a need for a high degree of coordination within this field. It is moreover important to recognise that the different actors have different approaches, guidelines and forms of organisation, and that there is limited formal contact between the various actors and knowledge of each other’s working methods and priorities. This places a demand on how efforts are organised, and ways to ensure dialogue and coordination between Norwegian political, military, humanitarian and development actors.

10.8 Proposal for initiatives within the peace, security and defence policy

10.8.1 Peace and reconciliation

Initiative 1. The Commission with the exception of Kristian Norheim is of the opinion that since conflict prevention and conflict reduction is of global significance as well as in Norway’s interest, and in addition an important tool in reducing poverty, the effort should be further strengthened and professionalised.

The foreign service should to a greater extent be oriented towards engagement in conflict areas. A number of countries have already reorganised their foreign service and assistance mechanisms towards conflict areas that constitute a global challenge. There is a need for a substantial reorganisation of the use of resources in the foreign service, in Norway and abroad, in order to handle the challenges such prioritising generates in a satisfactory manner.

The work to professionalize the peace and reconciliation engagement effort should be continued. The work should be knowledge-based and take place in close interaction with Norwegian and international research environments.

International networks should be further developed. Various actors can play different roles, from the UN, via nation states to private ones. Norway should further develop its role and position as a key supporter of such actors.

Norway must ensure that women are placed in key positions across the scope of the international involvement that Norway undertakes.

Norway must recognise children and youth as key actors in peace and reconstruction processes, and ensure that their perspectives and rights are secured in the international involvement that Norway undertakes.

10.8.2 Arms and the arms trade

Initiative 2. With the exception of Kristian Norheim and Julie Christiansen, the Commission is of the opinion that Norway needs to introduce an end user declaration also for sales of arms and ammunition to NATO countries, and set conditions for any onward sales.

Initiative 3. Norway must establish an export control council and closer involvement by the Storting in the approval of arms export licences.

Initiative 4. The Commission with the exception of Kristian Norheim is of the opinion that Norway must use its ownership interests in the Norwegian arms industry to ensure that the sale of arms and ammunition takes place in accordance with rules that are on a par with Norwegian rules, also with regard to sales from the industry’s factories in other countries.

Initiative 5. Norway must introduce tracing mechanisms for arms and ammunition. Arms and ammunition that are produced in Norway must be marked with information about manufacturer, first buyer and the production batch, and Norway must work towards a similar international labelling practice.

Information on the labelling practice and who has bought the weapon and ammunition must be kept on file and be accessible to third parties involved in tracing the products back to the manufacturer/seller.

Initiative 6. The Commission with the exception of Kristian Norheim is of the opinion that Norway should consistently use the UN’s authoritative hand weapon definition, regardless of whether the term is used in Norway export control contexts or in other contexts.

10.8.3 A UN-led world order

Initiative 7. With the exception of Kristian Norheim and Julie Christiansen, the Commission is of the opinion that Norway should prioritise military contributions to UN-led operations, but should also contribute with forces to NATO and EU-led operations when these are provided with the necessary legality by the UN Security Council.

Norway should actively take part in building capacity and expertise in regional organisations, including the secondment of specialist personnel when required. The purpose of this is to strengthen management and management structures in the organisations in order to make them more suited to preventing conflicts and carrying out peace missions, and thereby ensuring their legitimacy.

Commission members Audun Lysbakken, Lars Haltbrekken and Camilla Øvald refer to Initiative 7 in chapter 10 on the privisions for Norwegian military contributions to international operations. These members are of the opinion that Norway should seek a security policy foundation outside of NATO. Participation in NATO’s operations outside one’s own area will always entail a considerable risk that important NATO members’ own security policy and strategic interests will determine the priorities, and not considerations to development and ending of hostilities in the individual conflict-affected areas. The increased force contributions from western countries to NATO operations undermine the UN’s capacity and authority to take on the most important international missions. It is the view of these members that Norwegian participation in NATO’s international operations therefore constitutes a substantial coherence problem in relation to declared Norwegian goals of prioritising peace and development and working towards a stronger UN. These members are of the opinion that Norway should not contribute with military forces to EU-led operations, since Norway is not a member of the EU. These members’ primary view is therefore that Norwegian contributions to international operations should be reserved for UN organised operations. Within the framework of Norwegian NATO membership and the security policy directions that currently apply for Norwegian policies, however, the Commission’s proposal to place the highest priority on military contributions to UN-led operations will entail a development that these members regard as positive. These members have therefore endorsed the proposal.

Commission members Anne K. Grimsrud and Hilde Gjengedal do not find it appropriate to provide military forces to EU-led operations.

Commission member Kristian Norheim is of the opinion that Norway should prioritise military contributions to NATO-led operations, but should also contribute with military forces to EU and UN-led operations if the resource situation allows for it.

10.8.4 Integrated multidimensional operations and organisation

Initiative 8. The Commission is of the opinion that the Norwegian Government must undertake a review of the current organization of and routines linked to the preparation, initiation, execution and evaluation of integrated multidimensional missions in order to identify improvements that will ensure a greater degree of coherent policies for development and more multidisciplinary approaches at all levels of the decision-making processes.

The capacity to ensure the optimum coordination and multidisciplinary aspects linked to these operations should be strengthened considerably by the Office of the Prime Minister. The complexity of the challenges and the multidisciplinary aspects that are required in order to achieve the goals set require an overarching coordination that is independent from the specialist ministries.

At other levels, the work will be led by the specialist ministries according to their constitutional responsibility. Permanent consultation mechanisms should be devised to ensure that the multidisciplinary aspects in the work is observed at both a political and civil service level.

Knowledge of each others’ areas of responsibility is vital for effective collaboration and coordination. Permanent meeting points should therefore be established at both a political and civil service level, which includes the most involved parties. Security policy, development policy, legal and military views must all be involved directly in the decision-making processes.

The Government’s security Commission, various state secretary Commissions and permanent civil service groups should regularly discuss problems linked to integrated multidimensional missions and highlight questions related to development and humanitarian issues in these discussions. Likewise, military headquarters and other operational leadership should integrate multidisciplinary expertise.

In the long term, the multidisciplinary aspects and expertise in integrated multinational missions could be strengthened through a larger degree of exchange of employees between various ministries and subordinat institutions than what is present practise. Common components should be developed in the education systems for the police and the military forces. Consideration should be given to developing a special unit with civil military expertise, for example at the Norwegian Defence Education Command, for specialist environments to draw on.

A national council should be created for handling the entire range of Norway’s involvement within international crisis and conflict management and peace work. The council’s task would be to give advice on key problems linked to international multidimensional missions, and contribute with experiences linked to developing coherent policies for development and operationalising integrated operations. The council should have a broad composition, including civilian, military and humanitarian expertise in integrated multidimensional missions.

Footnotes

Collier, P. (2007). The Bottom Billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it New York, Oxford University Press.

The World Bank/ Human Security Report Project (2008). Mini Atlas of Human Security. Washington D.C., The World Bank/ Human Security Report Project.

UNDP (2007). Donor Proposal for the Eight Fold Agenda, New York, United Nation Development Program

The UN"s High-Level Panel (2004). A More Secured World: Our Shared Responsibility. New York, United Nations.

SIPRI (2008). SIPRI Yearbook 2008: Armaments, Disarmaments and International Security. Stockholm, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

Dan Smith and Janani Vivekananda (2007). A Climate of Conflict: The Links between Climate Change, Peace and War. London, International Alert.

Foreign Policy and the Fund for Peace. (2007). Failed States Index 2007, http://www.fundforpeace.org/web/ index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=99&Itemid=140.

Proposition to the Storting no. 48 (2007-2008): Et forsvar til vern om Norges sikkerhet, interesser og verdier (A defence to protect Norway’s security, interests and values).

Humansecurity-cities.org (2007). Human Security for an Urban Century: Local Challenges, Global Perspectives. Ottawa, Human Security Research and Outreach Program of Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada and Canadian Consortium on Human Security.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2007). Handlingsplan for Kvinners Rettigheter og Likestilling i Utviklingsarbeidet (Plan of action for women’s rights and equality in the development work), 2007 - 2009.

Bellamy, A. J. (2006). "Whither the Responsibility to Protect? Humanitarian Interventions and the 2005 World Summit " Ethics & International Affairs 20(2 (Summer 2006))

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2004). Utviklingspolitikkens bidrag til fredsbygging: Norges rolle (The development policy’s contribution to peace-building: Norway’s role). Oslo, Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (2007). Charting the Road to Peace: Fact, Figures and Trends in Conflict Resolution. Geneva, CHA.

Helgesen,V. (2007). "How Peace Diplomacy Lost Post 9/11: What Implications for Norway?"

OECD DAC (2007). OECD DAC Handbook on Security Sector Reform (SSR): Supporting Security and Justice. Paris, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Development Assistance Committee.

SIPRI. (2007). "SIPRI 2007 Yearbook", available at http://yearbook2007.sipri.org.

Marsh, N. (2007). Arms Export and Re-export. Oslo, PRIO.

http://www.forsvarsdialog.no/Default.aspx?tabid=113

From the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ website on Multidimensional and Integrated Peace Operations http://www.regjeringen.no/en/dep/ud/selected-topics/un/integratedmissions.html?id=465886

Barth-Eide, E., Kaspersen, A.T., Kent, R., von Hippel, K, (2005). Report on Integrated Missions: Practical Perspectives and Recommendations, The Expanded UN ECHA Core Group.

OCHA (2008). Civilian-Military Guidelines & Reference for Complex Emergencies. New York, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

NATO (2003). AJP-9 NATO Civilian-Military Cooperation (CIMIC) Doctrine NATO. 2007

Press release from «Speech at the NATO Meetings of the North Atlantic Council Brussels 26 January 2007» by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jonas Gahr Støre Ministry of Foreign Affairs 30.01.2007