3 What is consular assistance and how is it organised?

The consular field covers a wide range of activities, and it is difficult to find a single definition that provides an adequate description of what it entails. ‘Consular assistance’ is not a term with a clear legal definition, and its scope may change over time. Some tasks or services that were once commonly provided or were necessary for the Foreign Service to offer Norwegian citizens abroad are no longer relevant, while new tasks and services have been added to the list. A brief historical overview is provided in the next section, before further discussion of what is meant by consular assistance.

3.1 History

Norway’s aspiration to have its own foreign service and consular service triggered the dissolution of the union with Sweden in 1905. At that time, the consuls’ responsibilities revolved to a large extent around promoting and safeguarding Norwegian business interests abroad, particularly the interests of the shipping industry. The history of the Norwegian Foreign Service has therefore been inextricably linked to shipping, and much of the consular work described in historical sources concerns assistance to Norwegian shipping companies and seafarers. Although the Foreign Service is still responsible for providing assistance in cases involving shipping and the maritime industry, the context is now very different.

Figure 3.1 Norway’s own consular service

Norway’s aspiration to have its own consular service triggered the dissolution of the union with Sweden in 1905.

Illustration: Eget Konsulatvæsen (Our own consular service) by Olaf Krohn/National Library of Norway

Until relatively recently, travel to and communications with Norway were slow, and the diplomatic and consular missions therefore used to provide a number of consular services that are no longer relevant today. As recently as the early 1990s, the services set out in the Instructions for the Foreign Service as appropriate for missions to provide included forwarding post, acting as a depository for securities and transferring savings back to Norway. At the beginning of the 2000s, it was still quite common for missions to assist Norwegians with drawing up and registering wills and settling estates. The subsequent digitalisation of society and changes in political and other priorities mean that these tasks are no longer relevant for the missions, but new needs have emerged. For example, to follow up the long-term priorities of Norway’s integration policy, special representatives1 have been appointed to some missions to deal with individual consular cases involving negative social control and honour-motivated violence. The Foreign Service has also established positions for ID experts to strengthen efforts relating to establishing identity and checks of identity in immigration and consular cases.

The Indian Ocean tsunami in December 2004 was in many ways a turning point in the consular field both in Norway and in other countries. Most of the Norwegians directly affected by the disaster were tourists, and a white paper on the tsunami disaster and Norway’s central crisis management system was presented to the Storting in 2005 (St.meld. nr. 37 (2004–2005)). Experience drawn from the crisis formed an important part of the basis for the 2011 white paper on consular affairs Assistance to Norwegians abroad and thus also for the way consular work has been organised since then. The emergency preparedness system under the Foreign Service has been considerably strengthened in the last 20 years.

3.2 Consular assistance includes advice, services and help

The Norwegian authorities use the term ‘consular assistance’ to cover all forms of advice, services and help and support that Norwegian authorities provide to Norwegian citizens abroad. The term includes both statutory and non-statutory tasks, and also some tasks that the Norwegian state undertakes in its own interest.

Technological advances have made it possible for many tasks and services that previously required in-person attendance to be provided digitally. Within the Foreign Service’s field of responsibility, there has been a particularly marked change as regards maritime matters, where various tasks have been digitalised and transferred from the missions back to Norway. In the immigration field, the Foreign Service has also achieved good results by outsourcing services. This is a positive and planned course of development, which ensures better services and more effective use of resources. The development of improved public digital services is expected to continue, and all parts of the public sector should consider whether and how they can interact with Norwegians who are resident or staying outside Norway.

Consular advice

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs issues two types of general consular advice intended to prevent problems from arising. One of these is general travel information for all countries, which provides Norwegians with general guidance about issues it can be useful for travellers to be aware of or consider before visiting a country. The other is official travel warnings, which are issued in cases where there is reason to advise Norwegians to leave or avoid travelling to a specific country, area or region. These two forms of preventive consular assistance are described in more depth in chapter 4.

In some cases, it may be difficult to define and distinguish general advice on consular matters from advice and guidance provided directly by other public bodies. For example, it is quite clear that it is the responsibility of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health to give general advice on infection control and travel vaccines, and that people must contact the health services for advice about their own health. However, many Norwegians expect the Foreign Service to be able to answer questions about matters such as taxation, pension rights and access to health services, but questions in these areas must be addressed to the Norwegian Tax Administration, NAV (the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration) or Helfo (the Norwegian Health Economics Administration), respectively. In general, the Foreign Service should seek to avoid providing advice and guidance on matters that are the responsibility of other government agencies. The Government will seek to strengthen coordination between different Norwegian agencies on these matters.

Consular services

Most Norwegian citizens who meet up in person at a mission do so because they need a specific consular service. Each year, the Foreign Service issues around 20 000 passports, solemnises about 300 marriages and issues about 4 000 notarial certificates. In connection with the 2021 general election, some 7 500 overseas votes were received. Most of these consular services are governed by legislation administered by other ministries, and fees are charged for a number of them. These administrative services are described in more depth in chapter 5.

It is not possible for the Norwegian authorities to provide administrative services in every corner of the world that Norwegians travel to, but the Government will consider options for further digitalisation and for outsourcing to improve certain services.

Consular help for individuals

Help for individual people is the form of consular assistance that is most difficult to describe briefly and in general terms. This type of assistance will always be tailored to the individual, and the help provided will depend on the circumstances in a particular case. In many cases, the help the Norwegian authorities can provide is in practice limited to offering advice and guidance.

Other types of help given in individual cases may also include visiting Norwegians who are in prison abroad or forwarding information about a death to the Norwegian police so that they can notify the next of kin in Norway. Another example is that consular staff may need to report a concern about a person’s situation to the local authorities in a country so that they in turn can take steps to protect the person’s health and safety.

Every day, the Foreign Service follows up cases involving children and young people who are in difficult circumstances abroad. Missions in countries that are popular tourist destinations for Norwegians regularly experience situations where Norwegian children are abandoned for short periods of time as a result of their parents’ drug or alcohol abuse or mental health problems. Every year, the Foreign Service is also involved in cases where individuals are or may be subject to negative social control or honour-motivated violence while abroad. Consular help for individuals is described in more depth in chapter 6.

Consular crisis management

Occasionally, situations arise that affect large numbers of Norwegians at the same time and that require an extraordinary response and special measures. These are referred to as crises in this white paper.

There are no specific rules and regulations governing assistance to Norwegian citizens during crises abroad. In legal terms, any such assistance falls within the same category as all other consular assistance. This does not change even when decisions on special measures are taken during some crises.

The Norwegian authorities have dealt with a range of different crises abroad since the white paper Assistance to Norwegians abroad was published in 2011. In some cases, the Norwegian authorities offer assisted departure from dangerous situations or areas. Consular crisis management is described in more depth in chapter 7.

Figure 3.2 Assisted departure

The Embassy in Riyadh meeting Norwegian citizens arriving in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, from Sudan in April 2023.

Photo: Embassy in Riyadh/Ministry of Foreign Affairs

3.3 Who is eligible for consular assistance?

No one has a statutory right to consular assistance, but a fairly broad category of people may be eligible for some form of consular assistance from the Norwegian authorities. Whether or not consular assistance can be provided must be assessed on a case-by-case basis, and will depend on a person’s circumstances and the type of consular assistance they are requesting. Certain consular services can only be offered to Norwegian citizens, while for others the main criterion is that a person is resident in Norway. There are also services for which neither citizenship nor place of residence is relevant.

Textbox 3.1 Danish and Swedish rules on who can be offered consular assistance

Denmark: The consular services section of the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs works together with Danish embassies and consulates to assist Danish citizens and foreigners who are permanently resident in Denmark when they encounter problems abroad. Fees are charged for assistance provided by the Ministry or by a Danish embassy or consulate in another country.

Sweden: People in the categories listed in the Act relating to financial consular assistance are eligible for assistance from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and the embassies when they are abroad. These are:

-

Swedish citizens residing in Sweden.

-

Refugees and stateless persons residing in Sweden.

-

If there are special reasons, consular financial assistance can also be provided to a Swedish citizen not residing in Sweden, and a foreigner residing in Sweden. However, under the legislation, consular help for people who are not resident in Sweden is very restricted and will only be offered in exceptional cases.

Source: Websites of the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (www.um.dk) and the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs (www.regeringen.se).

Norwegian citizens

The Foreign Service is responsible for providing consular assistance to Norwegian citizens, and this is clearly expressed in section 1 of the Foreign Service Act. Most of the people who ask for and are offered various forms of consular assistance are Norwegian citizens.

The 2011 white paper Assistance to Norwegians abroad stated that in the Government’s view, higher priority should be given to assisting Norwegians on short trips abroad than to assisting those who are permanently resident in another country. However, there has been a widespread practice of providing consular assistance to Norwegians who are permanently resident abroad as well. Chapter 7 on crisis management includes further discussion of the limits of such assistance and whether rules should be introduced requiring people to demonstrate ties to Norway in addition to Norwegian citizenship in order to be eligible to receive consular assistance. This may be particularly relevant in the case of people who are citizens of more than one country.

Norwegian citizens who are also citizens of other countries will need to contact the authorities in these countries for queries in certain areas. For example, the Norwegian authorities cannot answer questions about citizenship of other countries, about other countries’ rules for issuing passports, or about other rights and obligations that follow from citizenship of another country, such as military service obligations. If a dual citizen is staying in another country of which they are a citizen, or enters a third country using a non-Norwegian passport, Norway’s ability to provide consular assistance may be restricted by the authorities of the country concerned. In some countries, for example, the Foreign Service does not have access to imprisoned Norwegians who are dual citizens because the country’s authorities do not recognise or allow consideration to be given to their Norwegian citizenship.

Non-Norwegian citizens

According to long-established practice, and as clarified in the legislative history of the Foreign Service Act, there may also be cases where it is natural for the Foreign Service to assist non-Norwegians. In this context, both the legislative history of the Act and the 2011 white paper Assistance to Norwegians abroad specifically mention non-Norwegians who are refugees or stateless and resident in Norway, and who therefore have a Norwegian travel document and use it when travelling abroad.2 Opportunities to receive consular assistance from their home country are likely to be very limited for people in these groups.

If other non-Norwegians ask the Norwegian authorities for consular assistance, they will normally be referred to the foreign service of the country where they are citizens. According to Statistics Norway’s population statistics, more than 600 000 non-Norwegian citizens were resident in Norway in 2024. None of these can expect to receive any form of consular assistance from Norway if they for example are arrested in a third country or while they are on holiday in their own home country.

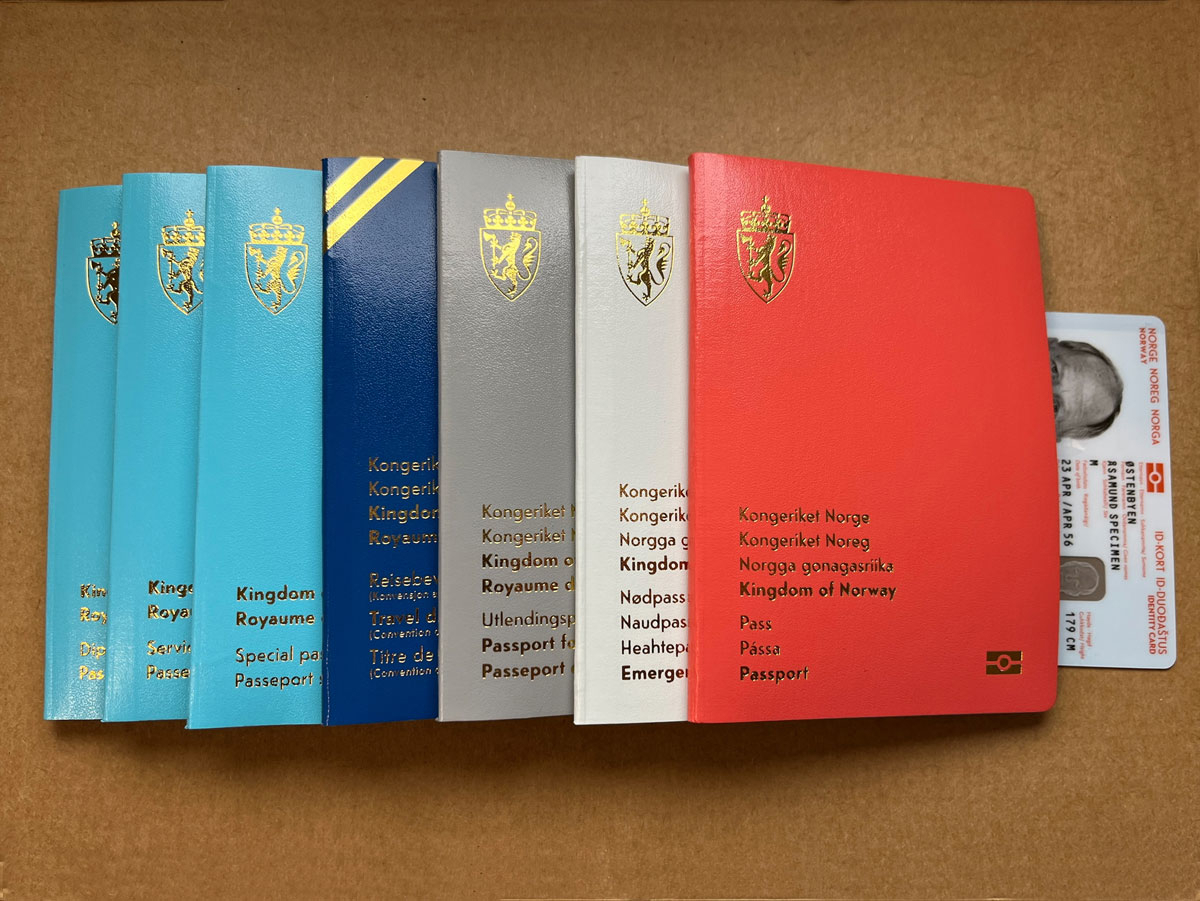

Figure 3.3 Different types of Norwegian travel documents

Anyone travelling on a Norwegian travel document can request consular assistance from the Norwegian authorities.

Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Legal entities

The Foreign Service Act (section 1, first paragraph, item 2) was amended in 2015 to make it clear that the Foreign Service is also responsible for providing assistance to Norwegian businesses and organisations. This amendment was in line with already existing practice, and was intended to reflect the responsibilities of the Foreign Service for promoting the Norwegian business sector abroad. Business promotion in itself is not considered to be consular assistance and is not further discussed in this white paper.

In the context of this white paper, this clarification is particularly useful in connection with crises abroad. Crisis management in the Foreign Service is to a large extent organised within the consular framework and context, and the 2015 amendment can be interpreted as meaning that legal entities can be the recipients of types of assistance that would normally be given to individuals. It is difficult to define in advance whether assistance from the Foreign Service in a particular situation is to be considered ‘consular assistance’ or something else (for example standard contact with the authorities on common administrative matters). The answer will depend on the actual situation and the specifics of the case. Some examples are described below.

Piracy was dealt with as a separate point in the 2011 white paper Assistance to Norwegians abroad. It is quite clear that the Foreign Service may have a responsibility to provide assistance to a Norwegian shipping company if a ship sailing under the Norwegian flag is attacked by pirates abroad or in international waters. During the COVID-19 pandemic, starting in 2020, the Foreign Service made every effort to assist Norwegian shipping companies and Norwegian-flagged ships with matters such as embarking and disembarking crew and entry permits. The aim was to maintain Norwegian shipping and global trade in very difficult and rapidly changing circumstances.

In 2013, 17 Statoil employees were caught up in a terrorist attack and hostage situation in Algeria. During the crisis, assistance from the Foreign Service was largely organised with Statoil as the main recipient. A number of other Norwegian actors organised their assistance in the same way. This approach may also be appropriate in other circumstances where an individual is in a difficult situation abroad as a result of where they are employed. The specific assistance that can be offered must be assessed on a case-by-case basis, but it will not normally be natural to offer substantial consular assistance to a Norwegian legal entity (a Norwegian company, foundation or the like) if most of the people affected by an incident are not Norwegian citizens.

Delimitation and clarification of the scope of consular assistance

Consular assistance is not an extension of or a substitute for employer responsibility or other types of responsibility that private or public legal entities have as regards their own employees, students or others who are affiliated with them.

This is something that also applies to government employees who are on official travel abroad or posted abroad outside the framework of the Foreign Service. In their case, consular assistance may supplement and support the efforts of a ministry or subordinate agency, but is not a substitute for their own employer responsibility.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has employer responsibility for its own employees. Each mission has employer responsibility for its own locally employed staff, and also a responsibility for other people who are affiliated with the mission, for example student interns. The consular assistance a mission can provide may be limited by the need to ensure the safety and security of employees. The Foreign Service has emergency preparedness plans, which for worst-case scenarios may include temporary closure of a mission and evacuation of personnel.3

In some situations, it is expedient for various governmental bodies to coordinate their responses closely. The withdrawal from Kabul in 2021 is an example of a situation where it would have been very difficult for the Foreign Service to continue to operate the mission safely, and then evacuate its personnel on its own. In addition, it is highly unlikely that the assisted departure from Kabul offered to other Norwegian citizens would have been practicable without the presence and assistance of the Norwegian Armed Forces.

Figure 3.4 The withdrawal from Kabul in 2021

Military personnel from various countries and other people seeking to leave Kabul in August 2021.

Photo: Norwegian Special Operations Commando/Norwegian Armed Forces

3.4 Legal framework

A combination of international and national law provides the basis for the consular assistance the Norwegian authorities can provide to Norwegians abroad, and also places certain constraints on this assistance.

3.4.1 International legal framework

Everyone has a duty to comply with the legislation that applies at any given time in the country they are in. This basic requirement follows from the principle of state sovereignty in international law.

Under international law, it is in principle up to each state to decide how it exercises authority in its own territory. However, international rules, for example human rights obligations, define limits for an individual state’s exercise of authority. As a general rule, it is the state where a person is staying that is responsible for ensuring compliance with such rights and obligations.

This means that the kind of assistance that the Norwegian authorities are able to provide to Norwegian citizens abroad is contingent not only on Norwegian legislation and policies, but also on the legislation of the country where that person happens to be.

The legal basis enabling the Norwegian authorities to provide consular assistance in other countries is derived from international law. The most important agreements for Norway in the field of consular affairs are the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations4 and the Helsinki Treaty on Nordic Cooperation.5 Norway is also a party to the European Convention on Consular Functions,6 and has entered into certain individual bilateral consular agreements.

International law, and particularly the Vienna Convention, makes it possible for Norway to provide consular assistance and consular services abroad. However, international law offers very little guidance on the specific scope of the assistance that can be provided.

3.4.2 Norwegian legal framework and internal rules

In Norwegian law, the overall framework for consular assistance is set out in the objects clause of the Foreign Service Act, which states that the Foreign Service is responsible for providing advice and assistance to Norwegian nationals.7 The Foreign Service has the primary responsibility for providing assistance to Norwegians abroad. The Foreign Service carries out its tasks either on its own behalf or on behalf of other Norwegian authorities and institutions.

Two of the Foreign Service’s three main tasks are related to consular affairs. According to section 1, first paragraph, items 2 and 3, of the Foreign Service Act, these tasks are:

-

2. to provide advice and assistance to Norwegian nationals and legal entities vis-à-vis foreign authorities, persons and institutions; and

-

3. to provide assistance to Norwegian nationals abroad, including assistance in connection with criminal prosecution, accidents, illness and death.

The Foreign Service Act does not use the term ‘consular assistance’, and does not seek to define what consular assistance means in practice. However, the legislative history of the Act mentions marriages and notarial acts as examples of consular services. Moreover, section 1, first paragraph, item 3, of the Act was amended in 2002 to include examples of the kinds of situations people requesting consular assistance may find themselves in. The purpose of the amendment was to provide the legal authority to process sensitive personal data. The provision has not been amended since the implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Norwegian law. It has been deemed necessary to assess whether the Foreign Service Act provides an adequate legal basis for processing of sensitive personal data in the field of consular affairs, and work on this has been initiated.

The provisions of the Foreign Service Act are supplemented by provisions in the Instructions for the Foreign Service. This is an internal document for the Foreign Service, largely dealing with the administration of the diplomatic and consular missions, but about one third of the document consists of detailed provisions regulating consular matters. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has also produced other internal guidelines on dealing with consular cases.

The Ministry has identified a need to further develop and modernise the consular framework and has initiated a process to further delimit and clarify the scope of consular assistance. The Government will give priority to this process. Guidance regarding the exercise of discretion in specific consular cases should as far as possible be publicly available, while at the same time taking into account the need to protect sensitive working methods from disclosure.

3.4.3 There is no legal right to consular assistance

Section 1 of the Foreign Service Act describes the tasks of the Foreign Service, but does not entitle individuals to require the intervention of the Foreign Service in specific cases, or to specify how it should intervene. Decisions on whether the Foreign Service should provide assistance in specific cases, and what consular assistance can be offered, are subject to the discretion of the public administration.

While the Foreign Service Act does not establish the scope of rights and duties in the consular field, these may be more clearly defined if a specific consular task or service is governed by other legislation. For example, many missions issue passports on a regular basis, and rights and duties in connection with this service are determined by the provisions of the Passport Act. Other relevant provisions, such as those of the Public Administration Act, also apply in full to this service. As regards the non-statutory element of consular assistance (advice and help), there are no formalised application procedures, and case processing does not normally involve individual decisions under the Public Administration Act or other formal decision-making. Nevertheless, there is an absolute requirement to exercise impartiality, which includes a prohibition on unfair discriminatory treatment. Consular assistance is offered with a degree of discretion and in line with the framework and principles for consular matters that follow from established administrative practice and this white paper. The principle of equal treatment is considered to be very important, and the Ministry coordinates activities globally to avoid the emergence of differing practices at different missions.

3.5 Organisation and use of resources

The Foreign Service consists of all Norway’s missions abroad and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Oslo. In this white paper, it is the embassies and consulates general abroad that are headed by a career officer (a foreign service officer posted abroad) that are relevant.

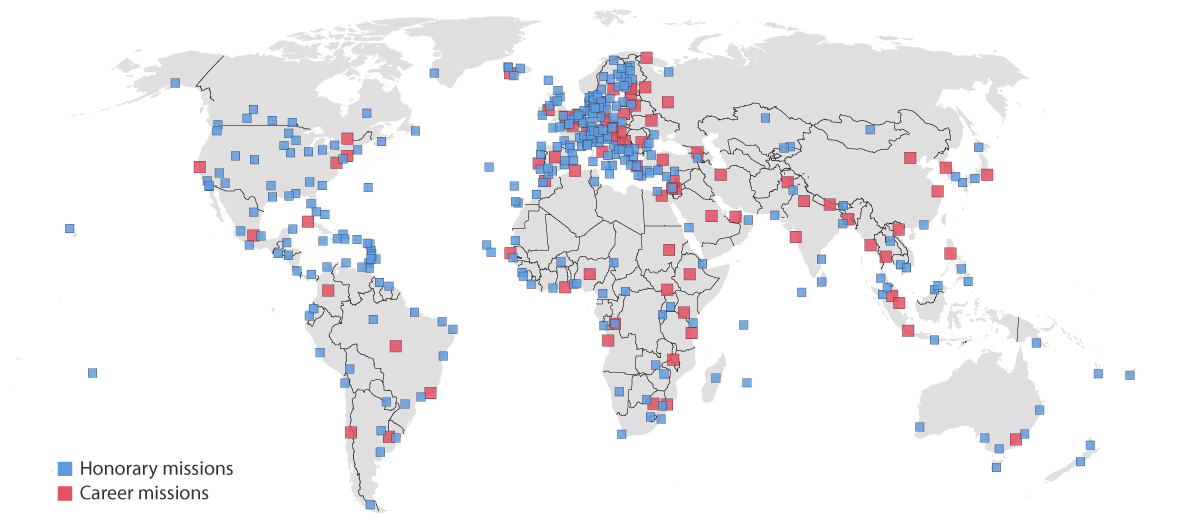

Norway has diplomatic relations with 196 countries, and as of spring 2025, had either an embassy or a consulate general headed by a career officer at 82 localities in 75 of these countries.8 In addition, Norway has about 300 honorary consulates in 125 different countries, and these are also an important part of the consular infrastructure.

3.5.1 The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the diplomatic and consular missions

The missions are responsible for a very wide range of tasks, including consular matters. All foreign service officers are prepared to deal with both consular cases and crises during a posting abroad. Consular cases and incidents may arise without warning, and elements of the work at a mission are inevitably reactive in nature and event-driven.

It is estimated that the missions use a total of around 200 person-years annually on consular matters.9 The total resource use is split between many different employees. At each mission, there is at least one posted foreign service officer with overall responsibility for consular matters and emergency planning. At a few missions, one or more posted employees work full-time on consular matters, but in general, such matters only make up a small part of the work of posted employees. Day-to-day consular work is to a large extent dealt with by locally employed staff, but posted employees, including ambassadors and consuls general, often assist in dealing with particularly complex individual cases.

Every year, the missions register more than 30 000 consular enquiries and cases, and in addition issue close to 20 000 passports. Aggregated data from the past five years show that an estimated 45 % of all consular enquiries concern advice and guidance to individuals. Many enquiries are about general questions that are uncomplicated for the missions to answer, for example by referring the person to already existing information on the internet or elsewhere. About 50 % of all cases dealt with by the missions involve administrative consular tasks. These largely consist of issuing passports and related tasks concerning children born abroad, but also include services such as notarisation.

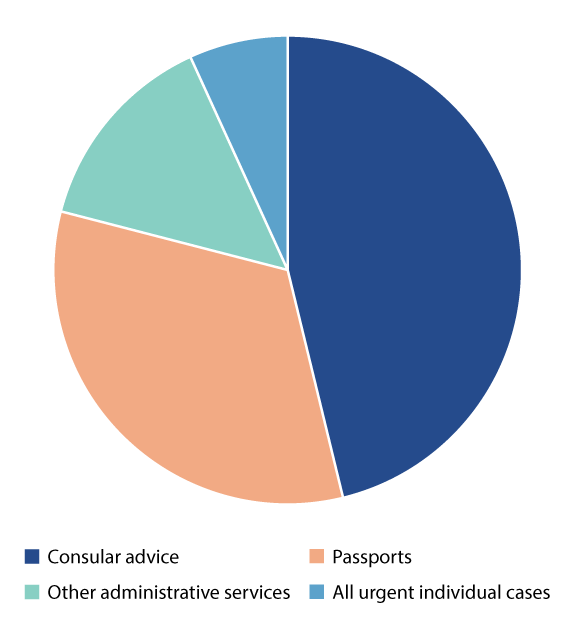

Figure 3.5 Distribution of different types of consular cases and enquiries

Administrative services account for about 50 % of all cases. Some 45 % of cases concern various types of advice and guidance. The remaining 5 % include all urgent individual cases.

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs

The remainder, approximately 5 % of consular cases and enquiries, includes everything except passports, other administrative tasks and general advice. Every data point in this category represents a case that the Foreign Service is dealing with or has dealt with, in contact with people who are in difficult situations. During the past five years, these have included several thousand cases involving deaths abroad or emergency assistance, and several hundred cases concerning people in prison abroad or child abductions. Although this category only makes up a small proportion of the total number of cases, it accounts for a large share of resource use.

Outside a mission’s opening hours, members of the public can contact UDops (the Foreign Service Response Centre) in Oslo. The centre receives about 16 000 calls a year. In general, it does not provide advice to the public or assist the missions with complex, lengthy individual cases. Such matters are dealt with by another section, which is also responsible for overall strategic work on consular affairs. In addition, the Ministry has crisis management teams on call to deal with major incidents and crises. In all, around 50 people in the Ministry work full-time on consular affairs and crisis management. In the event of a major crisis, all necessary resources are mobilised from other parts of the Ministry as well, as described in chapter 7.

Strategic work on consular affairs

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has overall responsibility for resource management and policy development in the field of consular affairs. The Ministry also carries out tasks that in other areas could have been the responsibility of a directorate or that would naturally be dealt with by an external executive agency. The fact that the Foreign Ministry deals with this field at both strategic and operational level is both a strength and a challenge. It is a recurring issue that progress in the overall strategic development of the consular field is hampered because resources have to be allocated to dealing with individual cases and crises that may threaten the health and safety of Norwegian citizens. The preparation of this white paper has provided an opportunity to take stock of what still needs to be done to further develop the consular field. A large proportion of consular assistance is based on practices reaching back many decades, in some cases probably more than a hundred years. An overall review is needed to further clarify certain aspects of the consular framework in more detail, and as mentioned in chapter 3.4.2, the Government will give priority to this work.

The Foreign Service is also seeking to shift resource use away from advice and guidance to individuals and towards better and more appropriate general advice to the public. This can be achieved through strategic communication activities and by using modern digital solutions to provide clearer, quality-assured and more cohesive information, so that individuals can find answers themselves.

3.5.2 Honorary consulates

Norway currently has about 300 honorary consulates. They are staffed by honorary consuls, who perform their duties for Norway without receiving a salary or other remuneration. Most of them (about 90 %) are not Norwegian citizens.

The role of the honorary consuls has changed since the dissolution of the union with Sweden in 1905. At that time, the consulates had close links with the Norwegian shipping industry and dealt with its needs for assistance. As more Norwegians began to travel abroad, it became important for the consulates to provide emergency assistance to travellers, for example people whose passports or money had been stolen. Many consulates have also played an important role for Norwegians resident abroad, who have been able to receive consular services such as having a passport issued.

Most of the services traditionally provided by the consulates have ceased to be relevant; for example, they no longer carry out routine tasks related to passports and immigration. Many of the honorary consuls now work mainly on other tasks to support the efforts of Foreign Service missions to safeguard Norway’s interests abroad. They may for example be involved in promoting cultural cooperation, providing advice to Norwegian companies and providing assistance during official visits from Norway. The honorary consuls have extensive local knowledge and networks, and are therefore in a good position to provide such services. This element of their work is not further discussed in this white paper, since it does not come within the scope of consular assistance. However, these are services that the consuls are continuing to carry out on behalf of the Foreign Service, and that should receive considerable attention in a future review of the system of honorary consulates.

There is wide variation from one consulate to another in how much of the workload consists of traditional consular tasks. In areas where many Norwegians are permanently resident, the consulates receive daily enquiries from people needing advice and assistance. From time to time, there is an urgent need for assistance, for example in connection with deaths, imprisonment or child welfare cases. However, enquiries most frequently concern a need for assistance that requires contact with other Norwegian authorities. The question is whether it is appropriate for the Foreign Service to undertake such tasks, or whether other agencies should have responsibility for this themselves.

Even though most of the honorary consuls no longer have much involvement in traditional consular tasks, we should not underestimate their importance on occasions when they are needed. They play a critical role as part of the emergency preparedness system, both when it comes to providing assistance to individuals and in connection with major crises. Many of the consuls are in countries where Norway has no embassy, and will play a crucial role for Norway for example if assisted departure needs to be organised. Norway’s consular infrastructure and emergency preparedness is considerably strengthened through the system of honorary consulates.

Figure 3.6 Norway’s consular presence abroad

The map shows a snapshot of where Norway had embassies and consulates general (career missions) and honorary consulates at the start of 2025. It includes two missions that were temporarily closed, and a few honorary consulates where the process of appointing a new consul was underway.

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Foreign Service expenditure on the operation of the honorary consulates is fairly low. The Norwegian authorities only cover specific expenses in certain circumstances. In 2024, the costs of office allowances and official expenses for all the honorary consulates totalled about NOK 21 million. A few consulates where the level of activity was high accounted for most of this, largely in the form of expenses for office premises and employees. For example, the consulates in Spain accounted for one third of total expenditure.

Nevertheless, the Government has identified a need to review the system of honorary consulates. At present, there are no satisfactory standards in place for administration of the consulates, and the regulatory framework and routines need to be updated to standardise operations. A clearer framework for administration of the consulates and clarification of what they are expected to provide as regards both traditional and new tasks will make it possible to use resources more effectively. The Ministry will therefore initiate a broad-based review of the tasks and administration of the honorary consulates.

3.5.3 International consular cooperation

There is regular dialogue between the foreign services of different countries on challenges and possible solutions in the field of consular affairs. Norway maintains a particularly close dialogue and structured cooperation with the other Nordic countries. The EU is an important partner in the area of crisis management. Norway also cooperates with the foreign services of other like-minded countries when this is natural, both in individual cases and when considering questions of principle.

Nordic cooperation on consular affairs

Norway cooperates closely with the other Nordic countries on consular matters, both with the services in the other Nordic capitals and with Nordic diplomatic and consular missions in third countries. The formal basis for Nordic cooperation on consular affairs is the 1962 Helsinki Treaty on Nordic Cooperation. Article 34 of the Treaty establishes that representatives of the foreign services of any of the Nordic countries are also to assist citizens of another Nordic country if that country is not represented in the territory concerned. Nordic cooperation also includes close cooperation in connection with crises.

Nordic working groups have been established in a number of consular areas, and officials from the five Nordic countries meet on a regular basis to coordinate activities and exchange information. There are also regular meetings of the Nordic and Baltic countries. Much of the cooperation deals with preventive measures, for example coordination of travel warnings and collaboration on crisis management. The extent of consular cooperation at missions varies from place to place, ranging from physical co-location and joint administrative support functions to mutual operational assistance in consular cases in connection with major incidents. The Nordic missions also generally cooperate closely on crisis management and emergency preparedness, as discussed in chapter 7.2.

Individual consular cases may also involve cooperation between the foreign services of Nordic countries. The level of assistance provided to citizens of other Nordic countries in such cases should not, in principle, exceed the level of assistance they could normally expect from their own foreign service. Assistance to citizens of other countries should be closely coordinated with the relevant Nordic mission or foreign ministry, which are responsible for making decisions in consular cases involving citizens of their own country. All the Nordic countries have set up 24/7 response centres that can be contacted outside office hours. Experience shows that providing consular assistance to citizens of other Nordic countries only accounts for a small proportion of the work at Norwegian missions.

Consular cooperation with the EU

The EU has for many years been seeking to improve coordination and cooperation in the consular field within the Union. However, the EU has encountered many of the same problems as the Nordic region, such as lack of harmonisation of legislation and differences in the practical organisation of consular assistance.

Under the Treaty of Lisbon, EU citizens have ‘the right to enjoy, in the territory of a third country in which the Member State of which they are nationals is not represented, the protection of the diplomatic and consular authorities of any Member State on the same conditions as the nationals of that State.’ To ensure implementation of this provision, steps are being taken to facilitate the exchange of information and improve coordination of the EU member states’ national efforts as regards both consular matters and crisis management.

The EU countries have made more progress in coordinating their visa arrangements. Norway has entered into agreements with several other Schengen countries on receiving and processing visa applications on each other’s behalf. This is possible because all the Schengen countries use the same legislation as a basis for processing applications, which is set out in the EU regulation known as the visa code. The Schengen countries and the European Commission cooperate on application of the legislation at many levels and in various forums in Brussels and locally at diplomatic and consular missions.

In practice, the most important element of consular cooperation between Norway and the EU concerns cooperation during major crises and when organising assisted departure from a crisis-affected area. This is described in more detail in chapter 7.2.

Figure 3.7 International consular cooperation

The Embassy in Budapest meeting Norwegian citizens who were provided with assisted departure from Sudan via Hungary. This was a result of international consular cooperation.

Photo: Norwegian Embassy in Budapest/Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Footnotes

A special representative is a foreign service officer from another government agency, posted to a mission for special purposes for a specified period of time, and temporarily employed by the Ministry.

This means either a refugee travel document or an immigrant’s passport. These documents are issued by the immigration authorities under the provisions of Chapter 12 of the Immigration Regulations.

The Ministry has used the term ‘evacuation’ in reference to its own employees, since as the employer it has the authority to issue instructions, for example to leave a mission. When other Norwegian citizens are given consular assistance to leave a country, the term ‘assisted departure’ is used. This is further described in chapter 7.3.

Vienna Convention on Consular Relations of 24 April 1963.

Treaty of Co-operation between Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden of 23 March 1962.

The European Convention on Consular Functions (ETS No. 61) entered into force in 2011 after ratification by five states: Norway (1976), Greece (1983), Portugal (1985), Spain (1987) and Georgia (2011).

The 1958 Foreign Service Act stated that the Foreign Service was responsible for providing advice, assistance and protection. This was amended in 2002, according to the legislative history, to make it clear that the Foreign Service does not and is not intended to ‘protect’ Norwegians in relation to foreign authorities, persons or institutions. Its task is to assist Norwegians in situations where problems have arisen or may arise.

This figure includes two missions that are temporarily closed.

In autumn 2020, a survey carried out in connection with a review of the Foreign Service estimated that the resources used totalled 164 person-years for locally employed staff and 33 person-years for posted employees. For the Foreign Service as a whole, the estimate is close to 250 person-years annually.