5 Administrative tasks – services to the public

Most consular matters involve administrative tasks that can be classified as consular assistance. This primarily concerns tasks relating to passports, marriages, notarial acts, legalisation of documents, letters rogatory, advance voting and matters relating to seafarers. There are also a variety of more peripheral tasks that the Foreign Service can carry out for other Norwegian authorities or for Norwegian citizens. In most cases, such tasks are governed by legislation that is the domain of other ministries.

The review of the consular services in this white paper will seek to identify and discuss challenges and dilemmas related to the scope and nature of the administrative consular services being provided and identify ways to further professionalise services and promote more effective use of resources.

5.1 Passports

The majority of passports issued to Norwegian citizens are issued in Norway, and the police issue some 700 000 passports annually. Norwegian missions abroad are also authorised to issue passports, and in 2024, a total of 80 missions1 processed roughly 19 000 passport applications.

Approximately 6 % of the passports issued by missions are emergency passports. Emergency passports are issued when an individual who is abroad urgently needs a new passport, for example because their ordinary passport has been lost or stolen, or has expired.

The remaining 94 % of passports issued at missions are ordinary passports that are being renewed or issued for the first time. The Foreign Service uses considerable resources on passport-related matters.

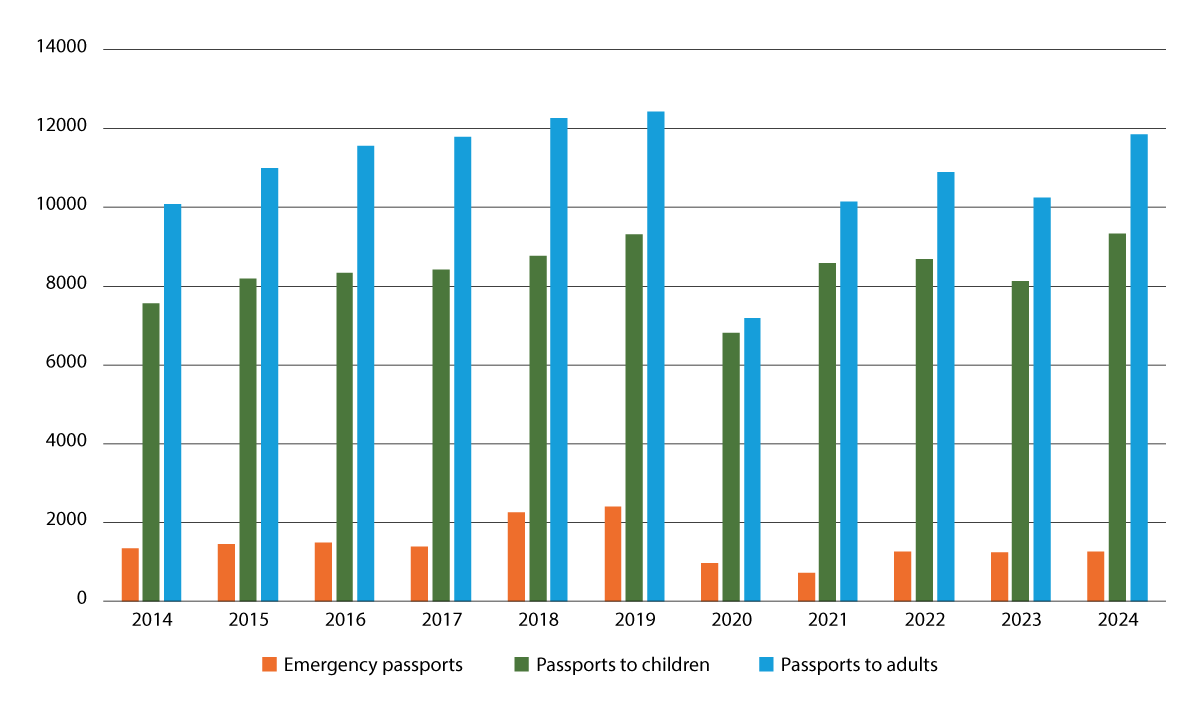

Figure 5.1 Passports issued at missions

The table shows the number of passports issued at Norwegian missions in the period 2014–2024, divided into emergency passports and ordinary passports to children (under 16 years of age) and adults (ordinary passports are valid for ten years from the age of 16).

Source: Police IT unit/Ministry of Foreign Affairs

In recent years, a reform to significantly enhance quality has been implemented in the passport field, and the number of passport offices in Norway has been reduced. To maintain the necessary processing quality and level of expertise, a passport office should, as a general rule, issue at least 4 000 passports annually. This reform has not been introduced for the Norwegian missions abroad. There are currently more passport offices abroad than in Norway, and none of the missions issue as many as 4 000 passports per year.2 Very few of the Foreign Service’s passport offices handle a high enough volume of cases for staff to gain sufficient practical experience.

Maintaining many small passport offices at various locations abroad poses a number of challenges relating to resource use and the ability to ensure the quality of the services. In light of this, together with the increased complexity of case processing and the pressure to streamline the distribution of the Foreign Service’s resources, the Government believes that the current system is no longer sustainable. The background and challenges to be dealt with are outlined in the Review of the Foreign Service.3

It is the Government’s view that Norwegian missions abroad should continue to issue emergency passports. However, it is necessary to reduce the services relating to ordinary passports that have been available to the public. Missions with very few foreign service officers and missions where it is difficult for other reasons to ensure the quality and security of case processing will no longer be authorised to issue ordinary passports. The question of which missions this will involve will be determined after further consideration.

The Government will also consider reducing the number of Norwegian missions in Europe to which applications for passport renewals can be submitted and consolidating this as a service to be provided by specific key missions. It will still be possible for other missions to process first-time applications for a passport. As part of this, consideration will also be given to whether the Embassies in Copenhagen and Stockholm should continue to accept passport applications, given their proximity to Norway. For example, the Swedish Embassy in Oslo no longer offers a service issuing ordinary passports to Swedish citizens in Norway.

The Government will also consider limiting the public’s ability to choose which mission to use when submitting applications for a passport abroad. The current freedom to choose makes it difficult for the missions abroad to predict the amount of passport work or organise it effectively. The missions are only equipped to receive a limited number of visitors, and expanding this capacity will entail significant costs.

In the long term, the Government will look at the possibilities for establishing agreements with external service providers on receiving applications for passport renewal. Such agreements have already been introduced in the UK and the Netherlands, for example. Cooperation with external service providers on passport-related issues has not been investigated so far, but the Norwegian authorities do have a similar agreement in place for receiving visa and residence permit applications. As is the case for these immigration cases, it is the practical tasks associated with the passport renewal application process that will be open to potential outsourcing. This includes collection of biometric data, identity checks (ID control), receipt of supporting documents and delivery of the finished passports. The processing and assessment of the applications will still be carried out at the relevant mission abroad. Outsourcing the system for application submission could be a means of maintaining passport services in places with increasing case volumes and large case portfolios. Otherwise, in order to maintain the passport service in such places, the alternative is to increase the number of posted employees to strengthen capacity, and in some cases this will also require expanding the buildings or leasing larger premises.

In 2024, the Foreign Service issued approximately 9 100 passports to children under the age of 16. These passports have a shorter validity period than adult passports, and the service providing passports to children will therefore need to be assessed separately.

Figure 5.2 Passport work at the missions

In 2024, approximately 19 000 Norwegian nationals submitted applications for passports at one of 80 missions. At most missions, it is the locally employed staff who register the incoming passport applications.

Photo: Embassy in Ankara/Ministry of Foreign Affairs

ID control and first-time applications for a passport

Each year, the Foreign Service processes approximately 3 000 cases involving first-time applications for passports for children born abroad. Unlike children born in Norway, children born abroad are not automatically registered by the Norwegian authorities. Norwegians living abroad are not required to inform the Norwegian authorities of the birth of a child abroad, and they are free to decide whether to apply for a passport for themselves and their children.

Cases involving first-time applications for passports for children born abroad can be particularly challenging, as the starting point always involves a child who has not been entered into any Norwegian registries. The Norwegian authorities then have no confirmed information regarding who the child’s parents are, and whether the child is a Norwegian citizen. These are questions that must be clarified in detail in connection with an application for a passport, and each case contains aspects that are regulated in four different acts of legislation. It is problematic for individuals and the Norwegian authorities alike that the provisions of the Children Act, Norwegian Nationality Act, Passport Act and Population Register Act are not harmonised. In some cases, it is necessary to carry out DNA testing to establish the relationship between a (presumed) parent and a child. This is time-consuming, and it is not unusual for a case to take several months before processing is completed. Furthermore, in certain cases, there may be serious considerations that weigh into the matter, such as considerations related to human trafficking and human rights violations.

In November 2024, the Government decided to appoint an interministerial working group with representatives of the relevant ministries and their subordinate agencies. The working group will take a closer look at the need for any legislative and organisational changes in the framework for clarifying the identity of children born abroad. It will identify inconsistencies and lack of harmonisation in the current legislation with a view to recommending further assessment of the need for amendments. The working group will also recommend further consideration of potential organisational or structural measures to ensure an adequate degree of control and establish more effective processes for establishing the identity of children born abroad. The aim of the recommended measures must be to prevent misuse of legislation and must safeguard the rights of children.

In its assessment of potential structural and organisational measures, the working group may also consider whether it would be beneficial to consolidate responsibility for decision-making relating to first-time applications for passports for children born abroad under a single unit located in Norway. This would facilitate close cooperation between all parties involved, establish a specialist group with expertise on these issues, and ensure equal treatment of applications, which are currently being submitted to and processed by 80 different passport offices abroad. It will also be of interest to identify which services the missions must be able to offer Norwegian citizens abroad on behalf of the Norwegian government administration, and the staffing and expertise that this will require. For example, it would be a good idea to consider the types of cases in which it should still be possible to submit a paternity claim at a mission. The working group will present a report with concrete recommendations by May 2025.

Figure 5.3 Emergency passports for assisted departures

The Embassy in Cairo and one of the Foreign Service’s ID experts at the border crossing from Gaza to Egypt in November 2023. While the surroundings in a crisis situation may look different from an office, emergency passports are still issued according to the rules that apply in other cases.

Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs

5.1.1 Surrogacy

Surrogacy is when a woman carries and gives birth to a child for another person or couple who are to be the child’s legal and social parent(s). The Norwegian authorities advise against the use of surrogacy abroad and do not provide assistance with surrogacy processes.

Nevertheless, some Norwegians choose to enter into surrogacy arrangements abroad. The general rules for establishing parentage and citizenship apply to children born through surrogacy as well. Under Norwegian law, it is the woman who gives birth to the child who is the child’s mother. In cases where the surrogate mother is a foreign national, the child’s father must be a Norwegian citizen in order for the child to acquire Norwegian citizenship from birth.

In surrogacy cases the missions only provide assistance with establishing the child’s identity, including paternity, and with processing passport applications in accordance with the general Norwegian rules. One of the challenges faced by the missions is that the authorities in some countries do not enter the surrogate mother’s name on the birth certificate, listing the name of the intended mother instead. Unless it is explicitly stated, it can be difficult for the missions to determine whether surrogacy has been used.

Some parents choose to return to Norway with the child without having been in contact with a mission. This is possible in cases where the child holds a passport from the surrogate mother’s home country and does not need a visa to enter Norway. In such cases the mission will only become involved if it receives a request for assistance from the Office for Children, Youth and Family Affairs (Bufetat) to obtain the surrogate mother’s consent to the child’s adoption. It may be difficult for the mission to make contact with the surrogate mother, both due to language and logistical issues and due to the length of time that has passed since the birth. By the time the adoption application is filed, the surrogate mother may consider the process to be over.

In order to ensure high-quality services and equal treatment in surrogacy cases as well, it would be beneficial for the processing of first-time passport applications for children born abroad to be carried out by a central unit or agency in Norway. This would help to build expertise in identifying surrogacy cases when this has not been disclosed in the case documents.

5.1.2 Adoption

People who are resident in Norway who wish to adopt a child abroad must first apply for prior consent from Bufetat. If prior consent has been obtained, a foreign adoption will as a rule be recognised in Norway and will have the same legal effect as a Norwegian adoption. If at least one of the adoptive parents is a Norwegian citizen, the child will automatically acquire Norwegian citizenship under the provisions of the Norwegian Nationality Act. Registration of the adoption or issuance of a Norwegian adoption order, registration in the National Population Register and allocation of a national identity number to the adopted child are all carried out after the child has moved to Norway. The parents must go to the tax office together with the child and register the child as having moved to Norway.

The missions only deal with a few adoption cases every year. The kind of assistance the families need from the Foreign Service depends on local factors, such as the emigration procedures applicable to the child and whether the child will also retain its original citizenship. In some cases it may be necessary for the mission to issue a Norwegian travel document for the child to be able to enter Norway. If the passport authorities have no clear objections, a temporary passport (emergency passport) without a national identity number may be issued to an adopted child. This is a practical solution generally considered to be acceptable and in line with the strict rules that apply to approved intercountry adoptions.

The missions may also be contacted by Norwegian citizens living abroad who have adopted a child through a domestic adoption process in the current country of residence and want the adoption to be recognised in Norway. Examples include adoption of the children of a non-Norwegian partner. Norwegians living in another country may apply to Bufetat for recognition of adoptions carried out abroad. Not all adoption decisions taken in another country are considered ‘adoptions’ under Norwegian rules.

There have been cases where people resident in Norway have adopted a child through a domestic adoption process in another country without obtaining prior consent from Bufetat. It is possible in such cases to apply to have the adoption recognised in Norway, but these applications are only approved in exceptional cases. There has been a sharp decline in intercountry adoptions to Norway in recent years, and the rules relating to intercountry adoption have been tightened. It is therefore conceivable that there will be a rise in the number of people adopting children through domestic adoption processes in other countries and subsequently trying to have these adoptions recognised in Norway.

5.2 Marriage

It is possible for Norwegian citizens to get married at certain missions. This is a consular service that is currently available at 23 of the missions, and some 300 wedding ceremonies are carried out at missions every year. This is a low volume of activity in administrative terms, and most of the marriages are solemnised at missions in Europe.

Norwegian citizens are not entitled to be married at a mission. The solemnisation of marriage has been offered at certain missions for largely historical reasons, and today this is very rarely defined as an essential consular task. A review of the Foreign Service was carried out in 2022. The subsequent report proposed discontinuing the practice of offering solemnisation of marriage at the missions. Some of the missions currently authorised to perform marriage ceremonies for Norwegian citizens would like to continue to do so and are making use of their spare capacity to deliver this service. It is up to each mission to determine how many marriage ceremonies it has the capacity to perform.

Detailed provisions on solemnisation of marriage at missions have over the years been set out in the Instructions for the Foreign Service, which was most recently updated in 2003, and in the separate Regulations of 21 May 2001 relating to the solemnisation of marriage by Norwegian Foreign Service officers (Norwegian only). These regulations have not yet been updated, for example to reflect the fact that the Norwegian Marriage Act was made gender-neutral in 2009. Efforts to amend the regulations are now under way and this work is expected to be completed by the time this white paper is presented to the Storting. In connection with this a recommendation will be put forward to make solemnisation of marriage at missions a service for which a fee is payable, in line with normal practice in Norway.

The rules on who is eligible to be married at a Norwegian mission vary from country to country. The Norwegian authorities require the approval of the authorities of the host country to be able to carry out official acts of this kind. If the authorities of the host country do not allow same-sex marriages, the mission may not solemnise such marriages. In all countries it is a requirement that one of the parties must be a Norwegian citizen and neither party may be a citizen of the host country. A list of the Norwegian missions authorised to solemnise marriages and who can get married where can be found on regjeringen.no (Norwegian only).

Figure 5.4 Performing a marriage ceremony at a mission

Norwegian Foreign Service employees at 23 missions carry out marriage ceremonies for around 300 couples every year. On 7 March 2025, two couples were married at the Embassy in Copenhagen.

Photo: Norwegian Embassy in Copenhagen / Ministry of Foreign Affairs

5.3 Matters related to seafarers and shipping

Norwegian shipping interests abroad are expanding. According to the Norwegian Shipowners’ Association, the Norwegian fleet has grown by approximately 30 % since the last white paper on consular affairs was published. Every day some 1 300 Norwegian-controlled vessels and rigs sail and operate in markets across the world. The Foreign Service cooperates closely with the industry.

Cooperation between the Foreign Service and the shipping industry does not revolve around consular assistance as it is understood today, but is often a combination of, or takes place in the interface between, consular assistance, crisis management, business promotion and general contact between national authorities. Norway’s shipping fleet is a unique emergency response resource that can be called upon when needed by the Foreign Service, especially in connection with evacuation by sea in a crisis situation.

Providing assistance to seafarers and the shipping industry has played a key role in the development of consular services, but today, the number of cases relating to seafarers is declining. In 2024 the Foreign Service registered 521 cases globally, of which 75 % were at the Embassy in Manila. The decrease in the number of cases is partly due to fact that the Norwegian Maritime Authority has modernised and digitalised many of its processes. This is a welcome development which helps reduce resource use at the missions while also enhancing the quality of case processing. One aspect that remains unchanged is that the missions can approve seafarers’ doctors on behalf of the Norwegian Maritime Authority. The Norwegian Shipowners’ Association has called for greater predictability in this area and has recommended further assessment of the approval process, including the role of the Foreign Service. There is a need to update some of the legislation in this area. Together with the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs will carry out a comprehensive review of the legislation and instructions assigning specific tasks relating to seafarers and shipping to the Foreign Service. The aim is to clarify the legal framework.

5.4 Notarial acts and legalisation

Every year, some 4 000 notarial acts are performed at the missions. The missions may, as a rule, carry out the same tasks that a notary public in Norway is authorised to perform.4 The job of the notary public is to verify facts. The most common types of notarial acts are: certification of a true copy of a document; verification of an original document; verification of signature; and verification of signature and authorisation to sign on behalf of a Norwegian enterprise.

The missions may perform notarial acts on behalf of Norwegian citizens or in cases where the matter is otherwise linked to Norway or Norwegian interests, and an assessment is carried out in each case to determine whether a notarial act may be performed. Documents issued in other countries will not be notarised, for example certified as true copies or original documents. If a Norwegian needs to obtain a notarised copy of their Norwegian passport, the mission may certify that it is a true copy of the original, but if the matter concerns a foreign passport, the individual concerned will be asked to contact the authorities of the issuing country.

Legalisation is a formal procedure, established as common practice, for giving an official document issued by the authorities in one country legal effect in another. Examples of relevant Norwegian documents in this context are birth certificates, certificates of no impediment to marriage/marriage licences, certificates of educational qualifications, and certificates issued by the Brønnøysund Register Centre. Legalisation refers to a certification process, whereby a document is certified by the foreign ministry in the issuing country and then again by the embassy or consulate of the country where the document is to be used.

The Apostille Convention,5 which Norway is party to, simplifies the legalisation process. A document to which an apostille has been affixed in Norway will be accepted by the authorities of a country that is party to the Convention, without the need for further certification.

As a general rule, under the procedure for carrying out legalisation of documents, this responsibility lies with a country’s foreign ministry. Documents issued by other countries for use in Norway must be legalised by the issuing country’s foreign ministry.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs legalises approximately 7 000 documents every year. All legalisation of documents is currently carried out by the Ministry in Oslo. Documents may be submitted either by post or delivered in person during the legalisation office’s opening hours (one morning a week). In connection with the Ministry’s move to the new government office complex, an assessment will be carried out of how best to provide these services as of 2026.

5.5 Letters rogatory

The Norwegian judicial authorities may request assistance from the authorities of another country in connection with a civil or criminal case. These formal requests for assistance are called ‘letters rogatory’ (or ‘letters of request’) and may be used, for example, in connection with the service of documents, examining witnesses, obtaining DNA samples, and the search and seizure or transmission of documents or other evidence. International judicial cooperation is regulated in a number of international agreements.

Where necessary, the Foreign Service can provide assistance to the judicial authorities in dealing with letters rogatory, and they do so with regard to approximately 550 letters rogatory every year, of which around 350 concern service of process.

The missions’ tasks in connection with letters rogatory largely involve providing assistance with transmitting documents between the Norwegian and foreign judicial authorities. Missions may, however, also be asked to carry out certain more concrete tasks, for example service of process and examination of witnesses.

Most countries permit other states’ consular officers to effect service of process on their fellow citizens in the host country. The way in which service of process is carried out varies from country to country and can involve delivering documents directly to an individual at their home or place of work or requiring the individual concerned to come to the mission. In some countries, service of process may be carried out by post, or with the help of a private delivery service. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs will assess, in consultation with the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, whether it may be possible to make greater use of digital solutions, particularly in cases where the party being served is in another country.

Sometimes the Norwegian judicial authorities ask a mission for assistance with taking witness statements from Norwegian citizens who are abroad.6 As a general rule, missions may comply with such requests if this is acceptable to the country in question and if the mission is given enough time to plan how to carry this out in practice. Usually this is a matter of providing a suitable venue and a video link and often of checking the identity of the witness. In most cases, a letter rogatory should be sent to the country concerned in advance, as many countries view remote examination of witnesses as an act that requires approval from the relevant national authorities.

5.6 Receipt of advance votes

The Foreign Service facilitates advance voting, enabling voters who are abroad to cast their ballots in advance in parliamentary elections to the Storting (Norwegian parliament) and Sámediggi (Sámi parliament) as well as in municipal and county council elections. Traditionally, advance voting has been available at all embassies and consulates general, and at some honorary consulates. Just as in Norway, organising advance voting is a relatively challenging task.

In connection with the 2021 general election, some 7 500 overseas votes were received. In the municipal elections in 2023, some 3 000 overseas votes were received. As part of its preparations for the elections that year, the Foreign Service distributed almost 19 000 physical ballot papers to 282 cities in other countries. A total of 1 180 kg of election materials were dispatched by courier from Oslo to 79 missions. The missions then forwarded some of the materials to honorary consulates where returning officers had been appointed.

No statistics or other data are kept on the number of advance votes received at specific locations abroad, but in 2023, at least 80 % of the official voting materials sent abroad were never used.

Considerable resources are used on sending election materials out to the missions and returning completed ballots to Norway. Under the Election Act, voters who are abroad may vote by post without visiting a mission in person, and they do not need to use official voting materials when doing so. A total of 287 postal votes were received in 2023.

The Government is proposing that in future the missions should no longer be sent election materials but should instead facilitate advance/postal voting by themselves printing out ballot papers and sending postal votes back to the polling stations in Norway. Missions that expect to deal with a large number of advance votes may still order election materials from Norway. Providing information about elections and how to cast ballots from abroad will remain a priority for the missions.

Figure 5.5 Election materials ready to be sent to the missions

A total of 1 180 kg of election materials were distributed to Norwegian missions and consulates in 2023.

Photo: Norwegian Directorate of Elections

5.7 Emergency loans

If something unforeseen happens abroad and the individual concerned does not have adequate travel insurance and cannot, for instance, afford to pay for a flight back to Norway, they must, as a rule, seek to obtain the necessary funds themselves or ask for help from family, friends or others. Employers may sometimes be willing to help by for example providing a salary advance payment. Once all other options have been exhausted, the individual may apply to the Foreign Service for an emergency loan. Repayments on these loans are collected by the Norwegian National Collection Agency. Failure to pay off a loan is grounds for the police to consider denying or revoking a passport.7

The practice of offering emergency loans is based on a long-standing tradition and is formalised in the Instructions for the Foreign Service. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has identified a need to further develop and modernise the consular framework, and this includes the emergency loan scheme. At present, the only way to apply for an emergency loan is by completing a paper form that has remained relatively unchanged for around 40 years. In exceptional circumstances, the Ministry may cover certain unexpected expenses in cases where the criteria for receiving an emergency loan have not been met but where it is necessary to provide assistance to protect life and health. Steps will therefore be taken to modernise and professionalise the administration of these schemes.

Emergency loans are also used in connection with assisted departures. While some people may genuinely need a loan, experience shows that the scheme is also used because the Foreign Service does not have systems or tools in place to receive user payments in real time while a crisis is ongoing. It is unfortunate that people who can afford to pay for themselves in practice have to take out a loan from the state. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs will be looking into other ways of receiving payments from the public.

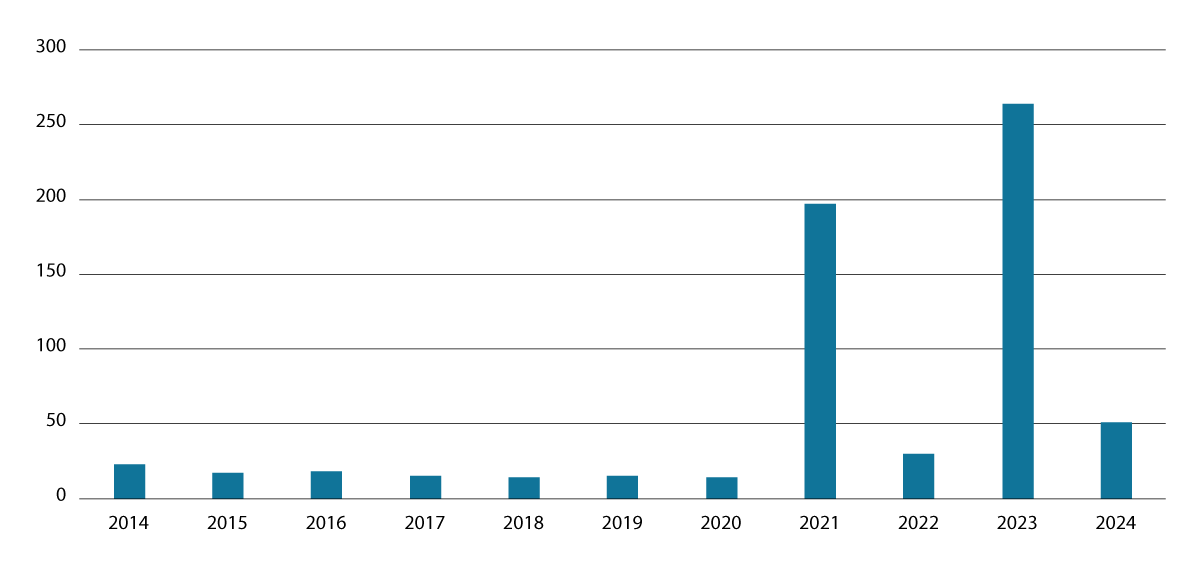

Over the past 10 years, the Foreign Service has sent around 700 cases concerning repayment of emergency loans to the Norwegian National Collection Agency. There was a spike in the number of cases in 2021 and 2023 because of various crises those years. It is estimated that the Foreign Service issues around 30 emergency loans in a ‘normal’ year. There has been a slight upward trend in recent years, unrelated to major crises. The average amount of an emergency loan over the past decade was approximately NOK 9 300. The total amount of the loans issued in the period 2014–2024 was approximately NOK 6 million. According to the Norwegian National Collection Agency, just over NOK 1 million of that sum was still outstanding at the end of 2024.

Figure 5.6 Number of emergency loans issued in the past decade

The figure shows the years in which cases concerning emergency loans were sent by the Foreign Service to the Norwegian National Collection Agency. Cases involving loans issued in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic were submitted in 2021. Loans issued in 2023 primarily relate to assisted departures from Israel and Gaza.

Source: Norwegian National Collection Agency/Ministry of Foreign Affairs

The Government considers the emergency loan scheme to be an important safety net that should be retained. It is important that the criteria are reviewed and clarified. This type of scheme should be regulated by law or regulations, and an assessment should be carried out to determine whether it can be managed more effectively. To be prepared for any contingency, it must still be possible to receive and process emergency loan applications manually, but the general rule should be that applications can be submitted digitally.

Footnotes

The figure includes two missions with passport authority (Kabul and Khartoum) which were temporarily closed in 2024 and physically relocated to other missions (Islamabad and Nairobi).

In 2024, the three largest passport offices abroad were at the Embassies in London, Copenhagen and Stockholm. The Embassies issued approximately 3 400, 1 800 and 1 200 passports respectively.

Deloitte and the Fridtjof Nansen Institute carried out a Review of the Foreign Service in 2021, at the request of the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The report is available on regjeringen.no (Norwegian only).

‘Notarial acts’ refers to the various tasks that notaries public are authorised by law to perform. The terms ‘notarial services’, ‘notarial certification’ and ‘notarisation’ are also used.

Hague Convention of 1961 (Convention Abolishing the Requirement of Legalisation for Foreign Public Documents)

Missions may in theory also provide assistance with taking out-of-court statements or taking evidence (consular court), but this is extremely rare.

See sections 5 and 7 of the Passport Act.