2 Background

2.1 Introduction

For thousands of years, sustainable use and protection of nature and biodiversity has provided the basis for human settlement and jobs within agriculture and forestry, fishing, hunting, harvesting, mining and industries linked to tourism throughout the country. For many people, nature plays an important part in deciding where to live and contributes to attractive and unique surroundings and experiences that influence identity, public health and the environment in rural and urban areas alike. We must use and manage nature in a manner that allows this to continue well into the future.

Although Norway has vast natural areas, they are not unlimited. Natural areas are being gradually developed and consumed – bit-by-bit. This has been ongoing for a long time and the cumulative impact may be too much. To ensure that future generations can continue to live good lives in, from and in harmony with nature, we need a more integrated approach to land-use management, which allows for both sustainable use and protection of biodiversity. In this report, the Government presents the policy to facilitate this. The Government will highlight principles for sustainable terrestrial and marine management that will contribute to reducing future development that result in loss of natural areas. Nevertheless, in cases where it is appropriate for natural areas to yield, purposes that serve critical societal needs, such as the production of renewable energy, will be given the highest priority. The Government is also increasing its efforts for nature restoration, and setting clear targets to reduce land development that leads to the loss of areas of especially high ecological value.

The Government believes that sustainable use and protection of nature is best achieved through a combination of strong national regulations and good long-term management at local level. It is the local authorities that have, and will continue to have, the responsibility for sustainable land management. This includes a responsibility to manage natural areas as a limited resource in a sustainable manner. The Government facilitates this through existing efforts such as the «Natursats» grants scheme. This White Paper presents additional measures that will enhance the ability of municipalities to steer local development in a sustainable direction. These actions have been drawn up with the aim of safeguarding local governance of natural land and to provide rural local authorities with the support to ensure development and viable local communities. The Government is committed to ensuring that local authorities have access to knowledge and adequate tools for this work. The Government’s efforts with nature accounting will provide more knowledge of the extent of biodiversity in Norway, the state of biodiversity and how biodiversity contributes to the economy and society. This will be important to enable local authorities to manage biodiversity even better than today.

This White Paper also constitutes the new Norwegian national biodiversity strategy and action plan (NBSAP). The action plan follows up the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework1 – hereinafter referred to as the KMGBF – which was agreed at in Montreal, Canada, at the 15th Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity in December 2022. All countries that are parties to the Biodiversity Convention must have NBSAP’s in place. The parties are expected to update their action plans in accordance with the KMGBF before the next Conference of the Parties, which is scheduled for autumn 2024.

The KMGBF is a response to global biodiversity challenges, which, among other things, have been identified by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). In 2019, IPBES published its first global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services.2 The report constitutes the largest and most thorough assessment of knowledge of the global state of biodiversity since 2005. In the report, IPBES presents knowledge based on more than 15,000 scientific sources and describes strong interlinkages between the state of biodiversity and its significance for human existence and welfare. IPBES describes how human activities have undermined ecosystems worldwide. Many of these negative impacts are irreversible or very challenging to reverse.

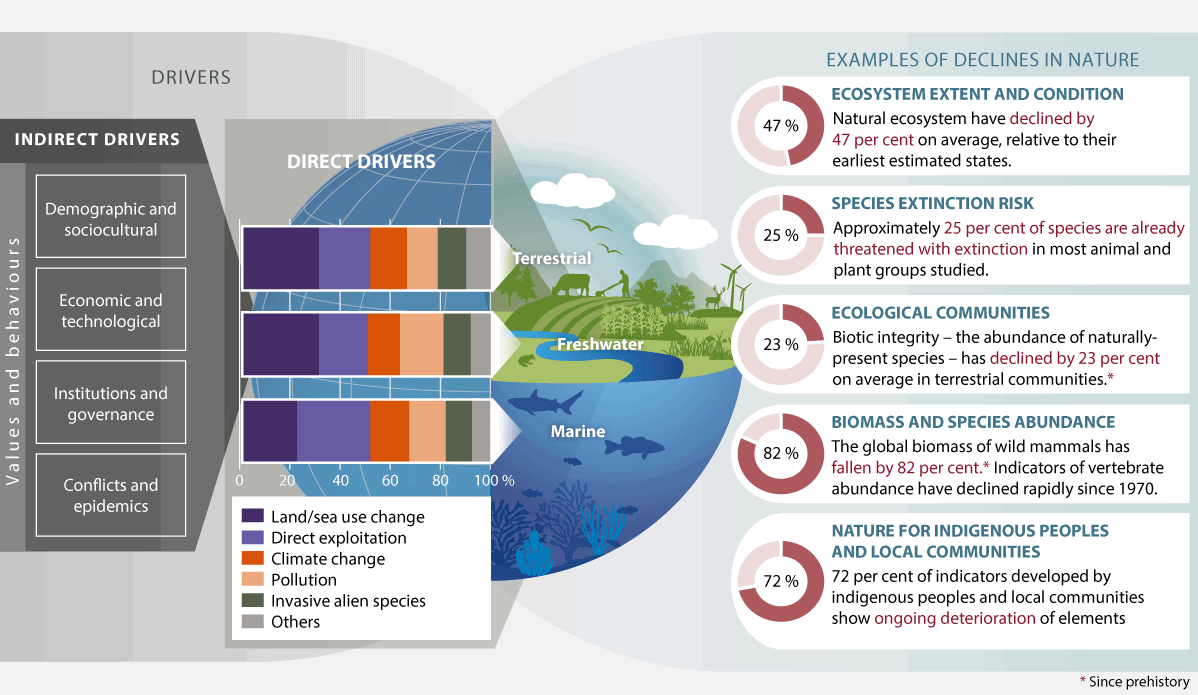

Textbox 2.1 Main findings from IPBES’ first global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services

IPBES, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, is a global science platform. In its 2019 global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services, IBPES assesses the research on the state, and development, of global biodiversity. IPBES reports that approximately 25 per cent of the species among the animal and plant groups assessed are endangered1 and estimates that around one million species are at risk of extinction,2 many within a few decades, unless action is taken to reduce the intensity of the drivers behind biodiversity loss. Failure to take such action will lead to the acceleration of global extinction, already taking place at a rate that is between 10 and 100 times higher than the average for the past ten million years.3

All parts of the biosphere – i.e. all living organisms and the areas on earth and in the air where there is organic life and that the entire human race is dependent on – are changing at an unprecedented pace. Biodiversity – that is, the diversity within species, between species and in ecosystems – is decreasing faster than ever before in human history.4

The direct drivers for biodiversity change with the greatest global impact have been (ranked by impact): changes to land and ocean use, over-harvesting, climate change, pollution and the proliferation of invasive alien species.5 These five direct drivers are, according to IPBES, caused by a number of indirect drivers, which include production and consumption patterns, population dynamics and trends, trade, technological innovations and governance.

Nevertheless, IPBES believes that biodiversity can be preserved, restored and used sustainably through immediate and coordinated efforts to trigger transformative societal changes, while also achieving other global societal targets.

1 According to the criteria of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/categories-and-criteria.

2 Purvis (2019).

3 IPBES (2019) p. XV–XVI.

4 IPBES (2019) p. XIV.

5 IPBES (2019).

Figure 2.1 Examples of global biodiversity changes

IPBES has demonstrated negative global biodiversity trends that have arisen or been caused by direct and indirect impacts (drivers of change).

Source: IPBES (2019)

Even though the state of biodiversity in Norway is, in many areas, better than in many other countries, the weakening of ecosystems described by IPBES on a global scale is also taking place in Norway. Land and sea use change constitute the greatest negative impact on Norwegian biodiversity.3 Biodiversity in Norway is also under threat from climate change, pollution, invasive alien species and over-harvesting.

The countries’ national policies, combined with international initiatives, will ensure that the global targets set out in the KMGBF are achieved. Through this NBSAP, the Government enables the continued sustainable use and protection of biodiversity in Norway, while also providing a key contribution to the global effort for global biodiversity.

Through this white paper, the Government is also following up on a request from the Storting of May 2021 to «[…] report back to them on the follow-up on the Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework in an appropriate manner as soon as possible after the Framework has been established».4

The KMGBF sets out how countries can reverse the negative trend of biodiversity loss. The Framework replaces the Biodiversity Convention’s strategic framework for 2011–2020, including the 20 global Aichi Biodiversity Targets.5 The KMGBF establishes four global goals towards 2050 and 23 global action-oriented targets towards 2030. These describe actions that must be initiated and implemented in order to achieve the global goals. Furthermore, the KMGBF includes associated decisions concerning monitoring, implementation mechanisms, resource mobilisation, capacity building and development, as well as digital sequence information. Norway was an active proponent of an ambitious framework, and the Government supports the KMGBF in full.

Textbox 2.2 The stewardship culture – management from the perspective of eternity

Norway has a long tradition of sustainable management of nature. The concept of responsible stewardship is a fundamental part of the Norwegian way of life.

This is evident from Norwegian agriculture, where there for generations has existed a moral imperative that farms should be passed on to the next generation in at least as good a condition as when they were upon inheritance. This includes not only buildings and routines but also respect for natural resources. The soil should not be exploited for short-term profits but rather be cultivated in a manner that maintains soil quality and harvesting potential for the future. Forests should not be harvested without ensuring that new trees are planted to the benefit of future generations.

This culture of stewardship is based on the understanding that the value of nature lies in its ability to give back as long as it is managed responsibly. Sustainable use is about balancing exploitation and conservation so that resources remain accessible and fertile for those who come after us.

The Government wishes to continue these deep-rooted Norwegian traditions of environmental stewardship by maintaining the principle of sustainable use as the primary approach to natural resources. Protection will remain a key tool, but not the only solution. The aim is for Norwegian nature and biodiversity to continue to be managed with respect for the long history of responsible use. This will ensure that we not only protect nature, but also that nature remains productive for future generations.

Table 2.1 Overview of the key terms used in the report

|

Term |

Explanation |

|---|---|

|

National responsibility species |

National responsibility species refers to species of which the Norwegian proportion of the European population constitutes 25 per cent or more. |

|

Area neutrality |

All physical loss of natural land is compensated for through the restoration of similar natural land. This is also referred to as net zero loss of nature. |

|

Species |

Groups of living organisms determined by biological criteria. |

|

Population |

A group of individuals of the same species living within a limited area at the same time. |

|

Biological diversity |

The diversity of ecosystems, species and genetic variations within species and the ecological links between these components. |

|

Sustainable use |

Use of components of biological diversity in a way and at a rate that does not lead to a long-term decline in biological diversity, thereby maintaining its potential to meet the needs and aspirations of present and future generations (Biodiversity Convention, 1992). |

|

Degraded ecosystem |

An ecosystem that is susceptible to changes or disruptions that have a negative and unwanted impact on the environment. |

|

Alien species |

An organism is considered alien to an area if its presence is due to human transport (consciously or unconsciously), and it has not previously occurred naturally in the area. In the work on ecological risk assessments of alien species in Norway, only species established with reproducing populations in Norway after the year 1800 are used. |

|

Genetic resources |

Genetic materials of actual or potential value (Biodiversity Convention, 1992). |

|

Major ecosystems |

Norway can be divided into several ecosystems. For the purposes of this report, Norway has been divided into the following seven major ecosystems: oceans and coasts, rivers and lakes, wetlands, forests, cultivated landscapes and open lowlands, mountains and polar ecosystems. |

|

Nature in Norway (NiN) |

Species and description system established by the Norwegian Species Data Bank. NiN describes all nature, from the large overarching landscapes down to the smallest of biotopes. The system has been developed to provide everyone working with nature and biodiversity with a common system of concepts. It is also a tool that can be used to describe variations in nature and to map nature and provide the basis for the work on assessing biotopes for the red list. |

|

Nature Index |

The Nature Index for Norway (NI) measures the state and development of biodiversity in relation to a reference state representing nature with limited human impact (with the exception of open lowlands), see box 3.1. |

|

Nature diversity |

An umbrella term for biological, geological and landscape diversity. It includes all diversity that is not largely a result of human influence (cf. Section 3 (i) of the Norwegian Natural Diversity Act). |

|

Biotopes |

Homogeneous environment encompassing living organisms and the environmental factors at work there, or special natural deposits such as boreal rainforests, hayfields or similar, as well as special types of geological deposits. |

|

Organisms |

Individual plants, animals, fungi and microorganisms, including all components capable of multiplying or transferring genetic material. |

|

Resilient ecosystems |

Refers to the endurance and resilience of ecosystems in the event of climate change and disruption. Endurance describes the ability of the ecosystem to withstand climate change and disruption and remain in a state of equilibrium. Resilience describes the ecosystem’s ability to recover following climate change and disruption. Even though the terms have not been strictly scientifically defined, both concepts are closely linked to ecological condition and maintaining the ecosystem’s variation and function. |

|

Endangered species |

Species (or subspecies) classified as Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN) or Vulnerable (VU) on the Norwegian Red List for Species. |

|

Endangered habitat type |

Biotope classified as Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN) or Vulnerable (VU) on the Norwegian Red List of Ecosystems and Habitat Types. |

|

Well-functioning ecosystem |

An ecosystem in which the natural ecological functions are maintained. A well-functioning ecosystem, in which most species and ecological functions are in place, will have good ecological integrity (see ecological integrity). Good ecological condition does not necessarily mean the ecosystem is pristine. |

|

Ecological functional area |

An area that fulfils an ecological function for a species. Some examples of ecological functional areas: spawning grounds, nursery grounds, migration routes, grazing areas, burrowing areas, hibernation areas. |

|

Ecological integrity |

Integrity is the degree to which an ecosystem’s composition, structure, and function are similar to its natural or reference state. |

|

Ecosystem |

A community of plants, animals and microorganisms and their interaction with the surrounding environment. Ecosystems work through upwards and downwards interactions in the food chain and with the physical and chemical environment surrounding the ecosystem. Ecosystems can vary widely in size and complexity. |

|

Ecosystem services (natural benefits) |

Benefits and services we get from nature. There are four main categories of ecosystem services. We distinguish between supporting, regulating, cultural and provisioning services. |

2.2 The importance of nature

Biodiversity encompasses all life on Earth and forms the foundation for human existence. The diversity of trees and plants, fish and other life in the oceans, birds, insects, mammals, fungi and other organisms sets Earth apart from any other planet we are familiar with. Nature is the foundation for clean air, water, food and a wide range of industries – from pharmaceuticals to construction materials. Nature is important for our mental and physical health and society’s ability to manage global change, health threats and disasters.6 In addition to nature’s importance to humans, nature and its diversity also holds inherent value.

When nature is degraded or destroyed, and species are threatened or become extinct, its ability to provide important ecosystem services declines. This can, lead to reduced nutrient cycling, poorer conditions for food production and less reliable access to other ecosystem services. Healthy, safe and resilient societies are therefore dependent on the protection of nature and the sustainable use of natural resources within ecological limits.

Ecosystem interconnectedness

Plants, animals, fungi and microorganisms interact with one another and with their physical environment to form ecosystems. Species within an ecosystem have different roles and positions in the food chain, and they create physical structures – such as trees or coral reefs – that provide habitats for other species (ecosystem structure). The processes that occur between species and their environment help sustain life on Earth (ecosystem functions).

The number of individuals of each species, the genetic variation within species, and the roles they play are all critical to how ecosystems function. Furthermore, the different interactions between organisms and the resulting food chain also affect how the ecosystem works. A greater diversity of species means that the ecosystem becomes more efficient at capturing and using resources such as sunlight, water and nutrients. Biodiversity rich ecosystems produce around twice as much biomass as monocultures of the same species, and these differences grow over time.7

A decline in a species’ population can also have serious consequences long before the species becomes extinct. For example, the collapse of cod populations off Newfoundland resulting from over-fishing triggered ecosystem changes that in turn have led to it becoming very difficult for the cod populations to rebound. In other cases, the loss of certain species within an ecosystem may initially have a minor impact on functions, as some species play overlapping roles. Nevertheless, continued species loss over time will result in a rapid reduction in ecosystem functions. Key species play a crucial role for other species, for example as food sources. If such key species disappear, the entire ecosystem may undergo radical change and food pyramids, for example, could be disturbed in irreversible ways. In the Norwegian Sea and Barents Sea, Calanus finmarchicus is one such key species that is a food source for herring, mackerel, cod and pollock.

When there is good ecological integrity, there is limited risk of the ecosystems reaching tipping points at which function and ability to supply ecosystems is sharply reduced. Ecosystems are also more likely to return to «regular» function after experiencing a disruptive event if the condition was originally good (see box 3.1 for details). Good ecological integrity is not necessarily the same as a natural state. In cultivated landscapes (semi-natural land) created through interaction between natural diversity and human use,8 status is assessed using other means.

The interlinkages between biodiversity and climate

Ecosystems are important carbon sinks because they capture CO2 through photosynthesis and store carbon in trees, soil, algae and sediment. Biodiversity rich ecosystems with good ecological status store carbon more reliably than degraded or damaged ecosystems – which may instead become additional sources of greenhouse gas emissions. One of the most effective climate actions is therefore to reduce the destruction of ecosystems in order to avoid the release of carbon from these natural stocks.9

Species and ecosystems are already being negatively affected by climate change. Loss of biodiversity and poor ecological integrity result in increased emissions which in turn amplify climate change, contributing to biodiversity loss, thus reinforcing one another in a negative feedback-loop.

Some ecosystems also help buffer the impacts of extreme weather caused by climate change. Forests and riparian vegetation along rivers and streams can reduce the risk of landslides and erosion, while wetlands in flood-prone areas can absorb and retain water.

Conserving ecosystems — both in terms of their extent and their ecological condition — is therefore essential for climate-resilient and sustainable development. It is also a prerequisite for a successful green transition.

The societal and economic value of biodiversity

Maintaining and safeguarding biodiversity provides significant societal and economic benefits.

Various economic estimates have been made of the value of nature, though such estimates are generally subject to uncertainty. For example, the conservation of wetlands along the world’s coastlines could generate global savings of approximately NOK 500 billion annually by reducing flood-related damages.10 The World Bank estimates that for every NOK invested in the establishment and management of protected areas and the facilitation of sustainable tourism, the economic return is at least sixfold.11 Globally, terrestrial protected areas receive around 8 billion visits each year, generating an estimated NOK 6,000 billion in spending.12 The economic benefits of preserving the remaining wild nature worldwide have been estimated to be at least 100 times greater than the potential economic gains from converting these areas to other uses.13

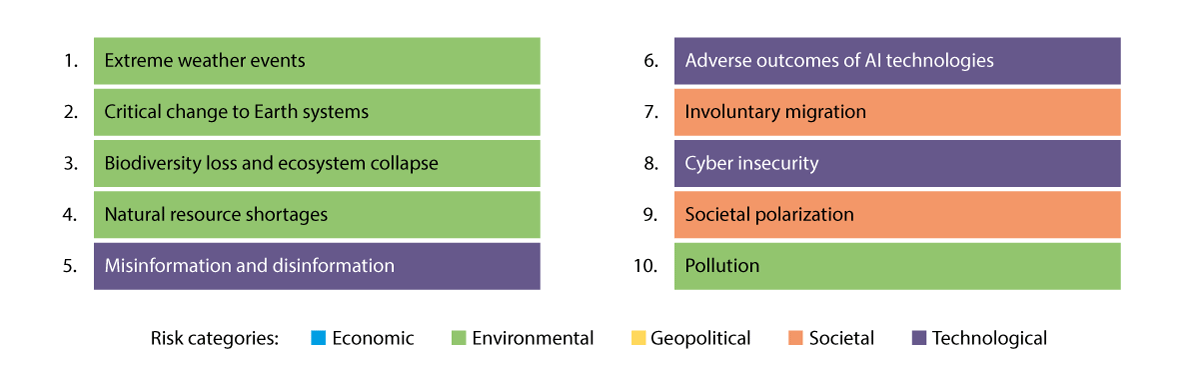

In its 2024 Global Risks Report, the World Economic Forum identified biodiversity loss as the third greatest risk to the global economy over the next decade — surpassed only by risks related to climate change, such as extreme weather and critical tipping points in Earth systems (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Global risks ranked by severity in the long term (10 years)

In its 2024 risk report, the World Economic Forum pointed to the loss of biodiversity as the third greatest risk to the world economy over the next decade, surpassed only by two risks associated with the climate (extreme weather and critical change to earth systems).

Source: World Economic Forum (2024)

The wide range of values we derive from nature — particularly those that are difficult or impossible to quantify, as well as public goods — are often not sufficiently considered in decision-making processes. In both large and small decisions, more immediate and visible interests tend to be prioritised. Actors who carry out physical disturbances in nature or engage in other activities that negatively affect biodiversity are rarely held accountable for the full social costs of their actions. While each actor’s contribution to environmental degradation may be small, the cumulative impact can be substantial.

A key message from the IPBES values assessment (2022) is that the root causes of the global biodiversity crisis — and the potential to address them — are closely linked to how nature is valued in political and economic decision-making at all levels.14 Despite the wide diversity of values associated with nature, most decision-making processes consider only a narrow set of them. According to IPBES, this undermines both nature and society, including the well-being of future generations. Furthermore, the values held by Indigenous Peoples and local communities are often ignored.15

IPBES suggests that this may stem from an underlying growth paradigm that treats nature as essentially free, or only valuable when harvested or converted for development. The key to addressing the biodiversity crisis, according to IPBES, lies in making the full range of nature’s values more visible and better integrated into decision-making processes.

2.3 Further information about the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF) was adopted at the 15th Conference of the parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. The Convention is discussed in more detail in box 2.3.

The purpose of the KMGBF is to halt and reverse the loss of biodiversity by establishing common global targets with associated actions that must be implemented rapidly to enable the restoration of biodiversity.

Both the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) emphasise that transformative societal change is necessary to address the crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. The 2019 IPBES Global Assessment Report states that «goals for conserving and sustainably using nature and achieving sustainability cannot be met by current trajectories. They may only be achieved through transformative changes across economic, social, political and technological factors.»16

Textbox 2.3 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is a global agreement on conservation, sustainable use of biodiversity and fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the use of genetic resources. It was adopted in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, together with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and UN Convention to Combat Desertification. The CBD entered into force on 29 December 1993.

The Convention is legally binding and has near universal participation, with 196 countries as parties.1 A key obligation is the duty of the parties to develop national biodiversity strategies and action plans. The Conference of the parties convene every two years to adopt decisions to advance the implementation of the convention. Decisions are not legally binding, but the parties are expected to follow them. The KMGBF is one such decision. All parties are required to report on the national implementation of the Convention.

1 A list of member countries can be found here: https://www.cbd.int/information/parties.shtml

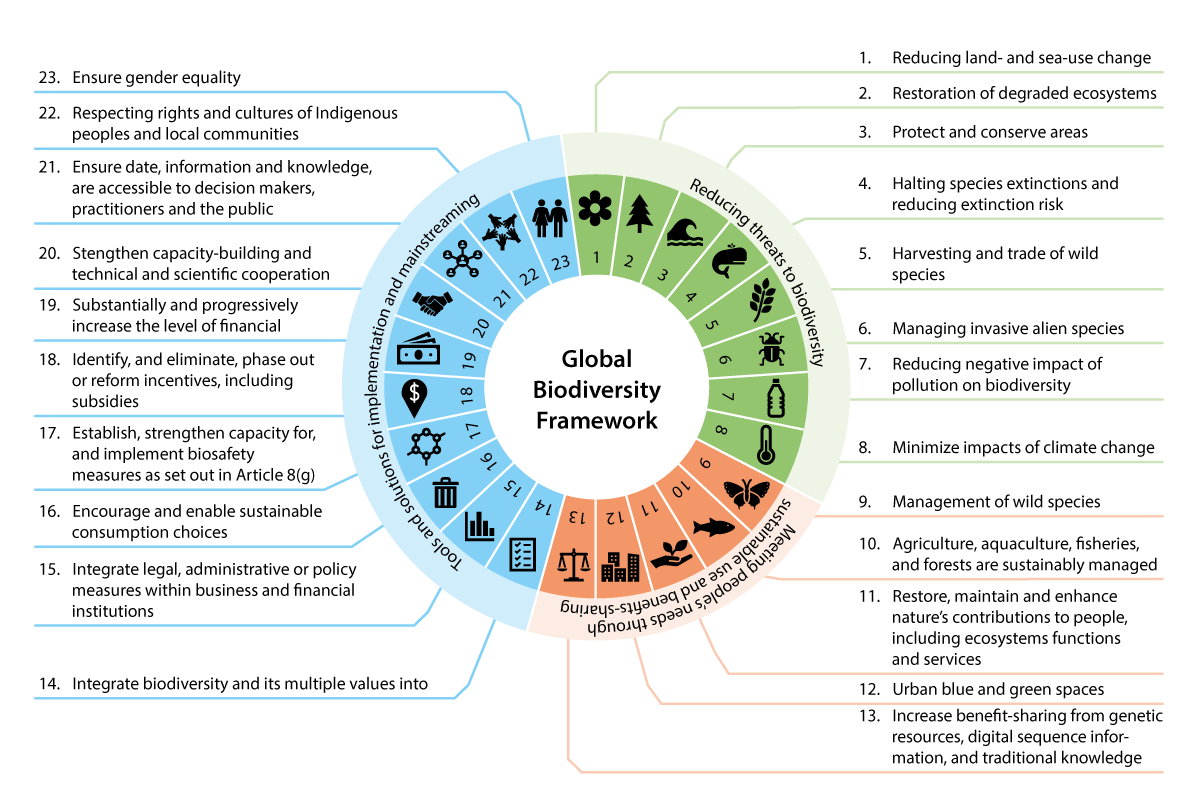

The targets of the KMGBF

As outlined in Chapter 2.1, the KMGBF includes four long-term goals for 2050, which describe a desired state for biodiversity, and 23 targets for 2030, which define specific actions and approaches that must be initiated and implemented to achieve the 2050 goals (see Figure 2.3).

The 23 targets for 2030 are grouped thematically into three categories:

-

Targets 1–8 focus on reducing threats to biodiversity, based on the main drivers of biodiversity loss and degradation identified by IPBES.

-

Targets 9–13 aim to meet people’s needs through sustainable use and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits.

-

Targets 14–23 address tools and solutions for implementation and mainstreaming.

Chapter 6 provides a detailed overview of each of the 23 targets and how they will be followed up by Norway as part of its NBSAP.

Figure 2.3 KMGBF targets

The KMGBF as a whole with each target grouped by overarching theme.

Source: The Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment

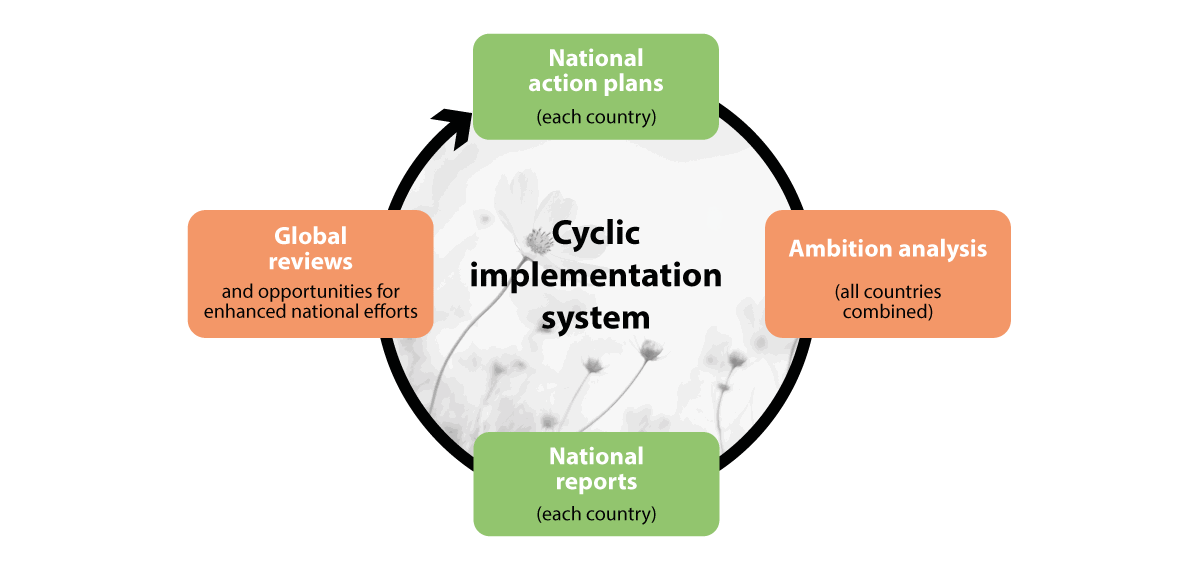

Implementation mechanism of the KMGBF

The KMGBF includes a dedicated implementation mechanism.17 This system is designed to ensure that countries follow up on their commitments to enable monitoring of progress during the implementation period up to 2030. It also allows for adjustments as necessary to achieve the global targets, see Figure 2.4. The main components of the implementation mechanism are:

Updated national biodiversity strategies and action plans (NBSAPs)

National action plans should be flexible and serve as effective national tools. They should include:

-

National targets for each of the global targets set out in the KMGBF

-

Concrete actions, policies and programmes designed to achieve the National targets and contribute to the global targets

-

National systems for monitoring and assessing of progress, including the use of the monitoring framework which is to be applied in reporting

Global analysis of the parties’ action plans

At each conference of the parties, an analysis of the countries’ overall ambition level for the implementation of the KMGBF will be presented based on the information available in the countries’ NBSAPs. This will take place in 2024, 2026, 2028 and 2030.

National reports on implementation

In 2026 and 2029, the countries will submit national reports showing progress towards the global targets and their corresponding National targets.

Global review of collective efforts

At COP 17 in 2026 and COP 19 in 2030, the parties will review the overall efforts made by parties. The review will be based on, inter alia, information from the countries’ national reports. Countries are encouraged to use information from the reviews to enhance their efforts.

The implementation mechanism also includes the existing system for voluntary peer reviews and allows for the development of additional voluntary mechanisms to assess national efforts. It also facilitates information sharing on contributions from non-state actors to the implementation of the KMGBF.

Figure 2.4 Cyclical implementation system

Source: The Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment

Monitoring framework

Although the KMGBF was adopted in its entirety by the Parties at the15th Conference of the parties, some elements are still to be developed and discussed towards the next COP. A key topic is the finalisation of the monitoring framework that will be used for 7th and 8th national reports. The monitoring framework consists of:

-

a. Headline indicators – a set of common and mandatory indicators that all countries must report on. These indicators are used to measure and summarise national and global progress and are intended to reflect the overarching purpose of the KMGBF.

-

b. Binary indicators – yes/no questions collected through standardised, classifiable responses in national reports.

-

c. Component indicators – optional indicators that countries may use to cover the various elements of the KMGBF targets.

-

d. Complementary indicators – optional indicators that can be used to provide more detailed reporting on specific themes.

Countries may also supplement these with national indicators.

These indicators will be central to national reports, which in turn will form the basis for the global progress reviews described above. See also the discussion of indicators under Target 21 in Chapter 6.

Considerations when implementing the KMGBF

The KMGBF includes several overarching considerations that countries must take into account when implementing the Framework (outlined in Section C of the KMGBF). Key considerations include human rights obligations, gender equality, and the principle of intergenerational equity. The KMGBF is a framework for all — encompassing all levels of government and society as a whole. Success will require coordinated efforts and collaboration across all sectors and levels of governance.

The KMGBF recognises the roles and contributions of Indigenous Peoples and local communities as stewards of biodiversity and as partners in conservation, protection, restoration, and sustainable use. Their rights and knowledge, including traditional knowledge, must be respected, documented, and preserved with their free, prior, and informed consent. They must also be enabled to participate fully and effectively in decision-making, in accordance with national legislation and international instruments.

All Parties must contribute to the achievement of the global targets in accordance with their national circumstances, priorities, and capacities. While the 1986 UN Declaration on the Right to Development is acknowledged, the KMGBF supports responsible and sustainable socioeconomic development that also contributes to the protection and sustainable use of biodiversity.

Implementation of the KMGBF must be based on an ecosystem approach — that is, the integrated management of land, water, and natural resources in a way that promotes conservation and sustainable use in a fair and equitable manner. Emphasising this approach helps to balance the three objectives of the Convention: conservation, sustainable use, and fair and equitable benefit-sharing.

The KMGBF also recognises the interlinkages between health and biodiversity. It calls for consideration of the One Health approach, which acknowledges that the health of people, animals (both domestic and wild), plants, and the wider environment — including ecosystems — are closely interconnected and interdependent (see further discussion in chapter 4.1.9).

Improved cooperation and synergies between the Convention on Biological Diversity and other relevant multilateral agreements, international organisations, and processes are also highlighted as an overarching consideration to support effective and appropriate implementation of the KMGBF. Part D of the agreement also makes special reference to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN Sustainable Development Goals).

2.4 UN Sustainable Development Goals and other international conventions, regulations, targets and processes of significance to Norwegian nature management

The United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity is one of the three Rio Conventions. It was adopted during the 1992 Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro, together with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification, as part of the follow-up to the Brundtland Commission’s report Our Common Future from 1987.

In addition to the Biodiversity Convention, other conventions and agreements also have an impact on the management of biodiversity in Norway. These include the Bern Convention, the Bonn Convention, the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA), the World Heritage Convention, the Ramsar Convention, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the Maritime Convention, the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR), the new Agreement on Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) and the European Landscape Convention. The UNFCCC and Paris Agreement, as well as conventions on different types of pollution, are also relevant.

Many of the EU’s climate and environmental rules are incorporated into Norwegian law as a result of the EEA Agreement. Conservation of nature and the management of natural resources are not covered under the EEA Agreement. Some legal acts of significance to biodiversity have nevertheless been incorporated into Norwegian law. Among others, the EU Water Framework Directive has been implemented through the Norwegian Water Regulation, the EU Directive on the deliberate release into the environment of genetically modified organisms has been implemented in the Act on the production and use of genetically modified organisms (the Norwegian Gene Technology Act) and the EU taxonomy for sustainable activities has been implemented in Norwegian law on sustainable finance.

The 2030 Agenda, including the SDGs, are the world’s shared work plan for the work on, and for achieving sustainable development. The 17 SDGs and 169 targets look at the environment, the economy and social sustainability together. Biodiversity is reflected well within the goals.

The SDGs were adopted at the UN General Assembly in 2015 and shall be achieved by 2030. All 193 member states are responsible for working towards goal attainment. This means that all countries have a responsibility to follow up, nationally and globally, to achieve the targets. The White paper no. 40 (2020–2021) Mål med mening – Norges handlingsplan for å nå bærekraftsmålene innen 2030 was presented in 2021 and considered by the Storting in 2022, (see recommendation no. 218 P (2021–2022) Innstilling fra kommunal- og forvaltningskomiteen om Mål med mening – Norges handlingsplan for å nå bærekraftsmålene innen 2030). A new white paper is being prepared and is scheduled to be presented before Easter 2025. In addition, the Government reports annually on the status of achieving the SDGs to the Storting. Every four years, Norway reports to the UN’s High-Level Political Forum (HLPF) on its work on the SDGs in Norway. Norway presented its second voluntary report on the status and progress of the work on the SDGs to the HLPF during the summer of 2021 and will present another report in 2025.

The action plan presented in this White paper will also contribute towards Norway’s work on the SDGs. The discussion in chapter 6 on Norway’s contributions to each of the targets in the KMGBF describes the SDGs each target is associated with.

An overview of the purposes of the various conventions and agreements on biodiversity, as well as the Water Framework Directive, can be found in table 2.2.

Table 2.2 Key international conventions and agreements on biodiversity

|

International conventions and agreements on biodiversity |

Main purpose |

|---|---|

|

United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) |

Global Convention with the purpose of conserving biodiversity, the sustainable use of its components and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits from the use of genetic resources. |

|

The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention on Biological Diversity (Cartagena Protocol) |

Protocol that contributes to the protection of biological diversity from potential threats from genetically modified organisms. |

|

The Nagoya protocol on Access and Benefit-Sharing to the Convention on Biological Diversity (Nagoya Protocol) |

Protocol on access to genetic resources and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilisation of genetic resources from flora and fauna, confirming that genetic resources are subject to sovereignty of the state and includes provisions on traditional knowledge. |

|

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) |

Global convention with the purpose of protecting endangered flora and fauna species from extinction as a consequence of international trade. |

|

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (Bonn Convention, CMS) |

Global convention with the overarching purpose of promoting the conservation of wild animal populations that regularly traverse national borders. |

|

Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat (Ramsar Convention) |

Global convention with the purpose of conserving wetlands, including both freshwater and marine areas. |

|

The World Heritage Convention (WHC) |

UNESCO global convention committing the parties to identify, conserve, preserve, disseminate and transmit to future generations the part of world heritage that may exist in their own territory. |

|

International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) |

Global convention with the purpose of preventing the introduction and spread of particularly harmful plant diseases and pests in connection with the export and import of plants and plant components. |

|

The International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (the Plant Treaty, ITPGRFA) |

Global treaty with the purpose of conserving and sustainably use of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture and ensuring fair and equitable benefit-sharing in accordance with the CBD so as to achieve sustainable agriculture and food security. |

|

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) |

Global convention governing peaceful use of the ocean and its resources. The convention covers all sea areas, the airspace above the ocean, the seabed and the subsoil thereof. Governs the rights and obligations of states in these areas and provides rules on environmental protection, marine research and technology transfer. |

|

United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA) |

Agreement on the implementation of the provisions in the UN Law of the Sea Convention. The agreement requires coastal states and states fishing in the high seas to participate in regional collaborations (establish Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) on the management of highly migratory and straddling fish species. The closest and most important RFMO for Norway is the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC). |

|

Agreement under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) |

The agreement strengthens and clarifies the Law of the Sea Convention’s provisions on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction. The agreement has been adopted but has not yet entered into force. |

|

Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Bern Convention) |

Regional convention covering all of Europe, but that is also open to other countries. The purpose is primarily to protect endangered and vulnerable species against over-exploitation, but also to protect wild flora and fauna and their habitats against other threats. A further purpose is to promote regional cooperation on the conservation of nature. |

|

Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR) |

Regional convention with the purpose of protecting and conserving the marine environment in the North-East Atlantic against adverse effects of human activities, thereby safeguarding human health and conserving marine ecosystems. Where practicable, the integrity of marine areas that have been adversely affected should be restored. |

|

European Landscape Convention |

Regional convention covering all of Europe but that is also open to other countries, with the purpose of promoting the conservation, management and planning of landscapes and organising cooperation in these areas. Implemented in Norway through the Planning and Building Act. |

|

EU Water Framework Directive |

A directive that is incorporated in the EEA Agreement with a view to contributing to conserving, protecting and improving bodies of water and the aquatic environment and ensuring sustainable use of water. Includes waterways, groundwater and coastal waters up to one nautical mile from the baseline. Implemented in Norway through the Norwegian Water Regulations. |

International agreements that do not primarily apply to the environment, such as trade agreements, establish frameworks and standards that impact the design and implementation of climate and environment actions. They can therefore also influence nature management in Norway. This may, for example, apply to EEA regulations in areas other than climate and the environment or agreements and obligations under the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

2.5 Norway’s climate and environmental goals

Norway has 24 overarching national environmental goals across the following priority areas: biodiversity, cultural heritage and cultural environments, outdoor recreation, pollution, climate change and the polar regions.18 The national climate and environmental goals define what Norway aims to achieve in each area and the desired state of the environment. International ambitions and obligations are reflected in the Government’s national goals. The national goals for biodiversity are:

-

ecosystems must be of good condition and deliver ecosystem services

-

no species or habitat types shall go extinct and the status of threatened and near-threatened species and habitat types must be improved

-

a representative selection of Norwegian biodiversity shall be conserved for future generations

These goals are fixed. The Government regularly reports on progress towards these goals in annual budget propositions to the Storting.

In addition to the overarching national goals for biodiversity, some more specific goals apply to specific species, habitats or ecosystems, such as the population goals for large carnivores as adopted by the Storting, including the predator agreements from 2004 and 2011, the population goal and designated zones for wolves from 2016 and the goal of 10 per cent forest conservation adopted by the Storting in Norway’s previous NBSAP Nature for life in 2016.19

Other sector-specific environmental targets and broader societal goals may also be of significance to biodiversity. These are addressed in more detail in Chapters 5.5 and 6.

2.6 Previous Norwegian biodiversity strategy and action plans

Norway’s first national biodiversity strategy and action plan can be found in the White paper no. 42 (2000–2001) Biologisk mangfold – Sektoransvar og samordning. The White paper was a tool for Norway’s follow-up on the UN Biodiversity Convention and recognised the need for a cross-sectoral national strategy and action plan on the management of biodiversity in accordance with the principles set out in the convention.20 Previously (1994), seven ministries had established sectoral action plans.21 Among other things, the report provided the basis for the establishment of the Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre and the development of the Nature Diversity Act.

In 2015, white paper no. 14 (2015–2016) Natur for livet – Norsk handlingsplan for naturmangfold was presented, which followed up on Norwegian obligations arising under the Biodiversity Convention’s strategic plan for 2011–2020, including the 20 Aichi targets. The white paper presented an account of what Norway had done to date to achieve the Aichi targets and the status of target attainment. The white paper highlighted the principle of evidence-based management and established the framework for increased efforts into the work on the ecological base map, the monitoring of nature and other knowledge collection, as well as providing the basis for more ecosystem-based management. This included work to develop an assessment system to clarify what is meant by good ecological condition in nature and how to set targets for ecological condition in ecosystems. The white paper announced the commencement of the work on supplementary protection to cover shortcomings in existing conservation efforts and emphasised an increased focus on voluntary forest conservation and continuation of the work on marine protection. In considering the white paper, the Storting adopted, among other things, a target of conserving at least 10 per cent of Norwegian forest areas.22

The white paper Nature for Life has been Norway’s national biodiversity strategy and action plan since it was presented in 2016 until now. The white paper presented here is based on policies with measures and actions established throughout the previous two reporting periods.

2.7 Work on the report – process and involvement

The Norwegian Environment Agency, together with other directorates, has drawn up a basis for the work on this White paper by evaluating the Norwegian biodiversity policy in relation to the new global targets and the status of the previous action plan.23

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework places great emphasis on broad involvement of all of society in the work to achieve the targets. The Ministry of Climate and Environment has arranged several consultations with civil society, young people, Indigenous Peoples and local communities, organisations and businesses in its work on the action plan. The first consultation took place in Oslo during the spring of 2023. During the period from November 2023 to January 2024, the Ministry arranged four regional consultations in Bergen, Tromsø, Oslo and Trondheim to obtain input on both the white paper on biodiversity and the upcoming white paper on the climate. Following these consultations, the Ministry received a lot of written input from the participants. The Ministry has also received input outside of these consultations. All input is publicly available at regjeringen.no.24

Overall, the input shows that many are concerned about the challenges relating to land and ocean use. It concerns, in particular, the municipalities’ role and dilemmas associated with land and ocean use, such as between the development of renewable energy technologies and the conservation of nature. Many parties have also provided specific proposals concerning instruments aimed at the use of land and oceans. Another common theme is the need for more knowledge, such as mapping, access to knowledge and increased biodiversity literacy. Restoration, conservation and preservation are recurring themes, and several respondents highlight the link between climate and biodiversity. The input shows that many respondents are positive to Norway contributing to achieving the targets set out in the KMGBF and that Norway is well-positioned to make a difference.

The Ministry of Climate and Environment had consultations with the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS) on the work on the white paper, both at political and administrative levels.

The Ministry also consulted the Sami Parliament on the work on the report, both at administrative and political levels. The Ministry also entered into dialogue with the Sami Reindeer Herders’ Association of Norway.

The Sami Parliament made three plenary resolutions in 2023 and 2024 that have been of particular importance to the Sami Parliament’s input to the report: Forventninger til nasjonal implementering av Naturavtalen, Vaarjelidh – Bevaring av naturmangfold and Samisk urfolkskunnskap i areal- og miljøforvaltningen.25

The Sami Parliament emphasises the importance of conserving biodiversity and ecosystems in Sápmi for future generations as the basis for Sami language, culture, social life and knowledge of indigenous people. The Sami Parliament expects the national implementation of the KMGBF to respect and acknowledge the rights, knowledge and practices of indigenous people in line with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. According to the Sami Parliament, traditional Sami use entails the best conservation of biodiversity, and the Sami Parliament expects traditional Sami knowledge to be acknowledged, recognised and safeguarded in the implementation. The Sami Parliament is clear that the loss of nature and climate change amplify one another and that the safeguarding of biodiversity must support climate adaptations for Sami industries. The Sami Parliament expects to be involved in decision-making processes affecting Sami areas and rightsholders.

The Sami Parliament highlights the need for new tools in environmental management through revised legislation that better acknowledges Sami use while also protecting nature against destructive intervention. The Sami Parliament also believes that there is a need to improve management practices so that the Government’s responsibility to protect Sami culture under international law does not become subordinate to traditional nature conservation in environmental management interpretations and practices. The Sami Parliament asks the Government to revise older protection regulations to acknowledge and protect Sami use. The Sami Parliament does not accept that conservation in some areas can lead to increased pressure in other areas without conservation status and wishes to develop new models for conservation areas in Sami regions based on international experiences with conservation areas initiated by indigenous people and the IUCN’s category VI protected areas with sustainable use of natural resources.

The Sami Parliament proposes that the Nature Diversity Act be evaluated to take a closer look at the use of the knowledge of indigenous Sami people in environmental management. The Sami Parliament also recommends amending regulations on environmental assessments to ensure that the knowledge of indigenous Sami people is included in assessments. Furthermore, the Sami Parliament proposes that a Sami reference group be established for quality control of the knowledge used in environmental assessments. The Sami Parliament asks the Government to set aside funds to strengthen capacity and expertise among Sami communities, organisations and knowledge-carriers so that they can participate in decision-making processes in a meaningful and culturally sustainable manner.

The Government finds that white paper does not contain any proposed measures that have any direct impact on Sami interests. Ordinary consultation procedures will apply when the report is implemented.

Footnotes

CBD (2022). The framework is available here: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf.

IPBES (2019).

The Norwegian Species Data Bank (2018) and the Norwegian Species Data Bank (2021).

Request no. 976 (2020–2021), cf. document 8:174 S (2020–2021) and recommendation no. 434 S (2020–2021) Recommendation from the Energy and Environment Committee on representative proposals for a strategy for the work on the UN Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Read more about the global Aichi targets here: https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets.

European Commission (2020).

Tilman, Forest and Cowels (2014).

See Chapter 4.6 Semi-naturlig mark («Semi-natural land») in Nybø and Evju (Ed.) (2017).

IPCC (2023), Figure 7 p. 27.

Barbier (2018).

World Bank (2021)

IPBES (2019) Chapter 2.3.

World Economic Forum (2024).

IPBES (2022)

NINA (2022)

IPBES (2019), summary for policymakers C.

Read more about the system for implementation here: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-06-en.pdf.

These targets were initially presented in the Ministry of Climate and Environment’s budget proposition for 2015. The targets replaced a number of more detailed targets. See proposition 1 P (2014–2015) Section 3 Chapters 7.1 and 9.1. The targets were included in the previous action plan, White paper no. 14 (2015–2016) Nature for life and were later repeated in annual budget propositions.

White paper no. 15 (2003–2004) Predators in Norwegian Nature, cf. Recommendation no. 174 (2003–2004) Recommendation from the Energy and Environment Committee on Predators in Norwegian Nature and Document 8:163 P (2010–2011), White paper no. 21 (2015–2016) Ulv i norsk natur – Bestandsmål for ulv og ulvesone and Recommendation no. 330 P (2015–2016) Innstilling fra energi- og miljøkomiteen om Ulv i norsk natur. Bestandsmål for ulv og ulvesone, Recommendation no. 294 P (2015–2016) Innstilling fra energi- og miljøkomiteen om Natur for livet – Norsk handlingsplan for naturmangfold, Storting resolution no. 667 (2015–2016).

White paper no. 42 (2000–2001) Biologisk mangfold – Sektoransvar og samordning Section 1.2.

Formerly the Ministry of Fisheries, Ministry of Defence, formerly the Ministry of Church, Education and Research, Ministry of Agriculture, formerly the Ministry of the Environment, formerly the Ministry of Trade and Energy and the Ministry of Transport and Communications.

Recommendation 294 P (2015–2016) Innstilling fra energi- og miljøkomiteen om Natur for livet – Norsk handlingsplan for naturmangfold, Storting resolution no. 667 (2015–2016).

The Norwegian Environment Agency (undated. -a).

The input is available using the drop-down menu at the bottom of the page here: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/apent-innspillsmote-om-naturavtalen/id2973455/ and here: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/regionale-innspillsmoter-om-stortingsmeldinger-for-klima-og-naturmangfold/id3014889/.

Sami Parliament reference 048/23, 059/23 and 023/24. The plenary proceedings of the Sami Parliament are available at: https://sametinget.no/politikk/plenumssaker/.