6 Norway’s commitments to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework

Chapter 2 provides the background and structure of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Chapter 6 outlines Norway’s contributions to each of the 23 global targets in the agreement. Through its national targets, Norway also contributes to the four global goals of the KMGBF, which are further described in Chapter 6.24.

6.1 Target 1 – Plan and Manage all Areas to Reduce Biodiversity Loss

6.1.1 Global target

Ensure that all areas are under participatory, integrated and biodiversity inclusive spatial planning and/or effective management processes addressing land- and sea-use change, to bring the loss of areas of high biodiversity importance, including ecosystems of high ecological integrity, close to zero by 2030, while respecting the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities.

This target is linked to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, sub-goals 14.2, 15.1, 15.2, 15.5 and 15.9.

6.1.2 Status in Norway

The Norwegian Planning and Building Act applies to mainland Norway as a whole, as well as ocean regions up to one nautical mile outside the baseline. The Act will promote sustainable development in the best interests of individuals, society and future generations. Planning in accordance with this Act shall facilitate the coordination of central, regional and municipal functions and provide a basis for decisions regarding the use and conservation of resources. Participation will be facilitated for all affected stakeholders and authorities. Municipalities constitute the local planning authority and manage the majority of land areas.

The planning of energy plants follows many of the same rules set out in the Norwegian Planning and Building Act, even though the permits are issued under other regulations. For wind power plants with a capacity exceeding 1 MW, there must be a local area zoning plan in place before a license can be issued pursuant to the Norwegian Energy Act. This does not apply to licenses for hydropower plants and power grid installations.

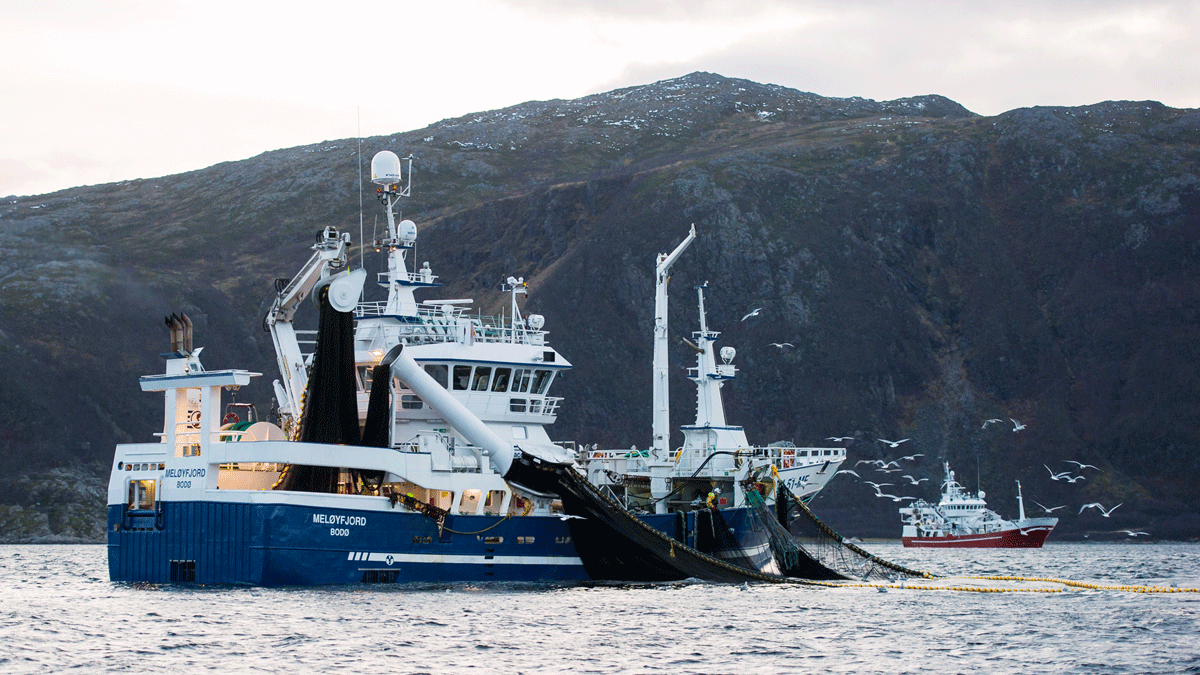

In marine waters that fall outside the scope of the Norwegian Planning and Building Act (one nautical mile from the baseline), the central authorities clarify and govern marine area use through integrated management plans for Norwegian sea areas and sectoral legislation, such as the Aquaculture Act, the Marine Resources Act, the Petroleum Act, the Offshore Energy Act and the Seabed Minerals Act. The integrated management plans for the sea areas clarify an overall framework and encourage closer coordination and clear priorities for the management plan areas. The ocean management plans are intended to provide an overall balance between use and conservation based on knowledge of the natural environment together with knowledge of current and future activities and value creation. For example, an area-specific framework is established for petroleum activities. Terrestrial and marine protected areas under to the Nature Diversity Act are subject to tailored regulations detailing which activities that are permitted in the relevant protected area. Sectoral legislation can also contribute measures to the conservation of biodiversity. The Government has also presented an Ocean Industry Plan for Norwegian sea areas with ten overarching principles for marine area use, contributing to strengthened cross-sectoral coordination, increased predictability for users of the ocean and co-existence. Svalbard is primarily managed based on the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act, which sets out tailored provisions for both protected areas and spatial planning in local communities. Information on spatial disturbances in Svalbard is well-documented. Here, there is a close to zero loss of land that is important to biodiversity and currently of good ecological integrity. This applies to loss resulting from land use and does not take into account loss of e.g. sea ice habitats due to climate change.

In general, Norway’s terrestrial and marine areas are subject to spatial planning and/or effective management processes. These regulations and processes include the balancing of all societal considerations, including biodiversity.

Textbox 6.1 The Norwegian Planning and Building Act and its instruments

The Norwegian Planning and Building Act governs the use and conservation of land and resources. It is cross-sectoral and generally applies to all types of activities and measures within the scope of application of the act.

Local authorities must draw up a planning strategy every four years. The planning strategy should include a discussion of the local authority’s strategic choices linked to social development, including long-term land use, environmental challenges, sectoral activities and an assessment of the local authority’s planning requirements in the election period before determining whether there is a need for any changes to the municipal master plan. In its work on the planning strategy, the local authority must also consider whether there is a need to initiate work on new land use plans during the election period or whether the prevailing plans should be revised or repealed.

All local authorities should have a municipal master plan that includes a social element with a programme of action, and a land-use element. The social element of the municipal master plan includes targets and strategies for the development of the local community and the local authority as an organisation. The land-use element of the municipal master plan establishes future land use based on the targets for social development set out in the social element. This must specify the main traits of land use allocation, frameworks and conditions under which new measures and new land use can be implemented, as well as any important considerations relating to the allocation of land.

The local authorities also adopt zoning plans that specify development solutions in limited areas. There are two different types of zoning plans: area zoning plans for larger areas and detailed zoning plans for smaller areas. Private parties can present proposals for detailed zoning plans within the framework of the land-use element of the municipal master plan and area zoning plans. The local authority can also choose to entrust the area zoning plan work to the private sector. Intermunicipal plans are drawn up by two or more local authorities when appropriate for the purpose of coordinating planning across municipal borders.

The County Councils are the regional planning authority. They will draw up regional planning strategies every four years and will draw up regional master plans in line with the planning strategies. Regional master plans are adopted by the County Council. A regional master plan has no direct legal impact on residents but will form the basis for municipal, county municipal and governmental planning and activities. Regional master plans can contribute towards coordination across municipal borders and a comprehensive assessment of land use in larger regions. Regional authorities can, among other things, establish land zones that provide direction for local planning. The regional planning authority can establish regional planning provisions, including prohibitions on specific measures for up to ten years in order to safeguard national or regional considerations and interests.

The Norwegian Planning and Building Act also establishes national planning activities. Every four years, the Government presents its expectations regarding regional and local planning. The Government may issue government planning guidelines that will form the basis for central, regional and local planning under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act and individual decisions pursuant to the Norwegian Planning and Building Act and other legislation. The Government may also set down central government planning provisions that entail prohibitions against specific construction and civil engineering initiatives and other measures for a period of up to ten years. Central government land-use plans may also be drawn up.

Sustainable land-use management that safeguards considerations for biodiversity assumes that decisions on land use are made on the basis of knowledge of natural assets and the impact that development projects and physical disturbances will have for such assets. Sections 8 to 12 of the Norwegian Nature Diversity Act set out the principles for public decision-making, see more about these in Chapter 6.14.2. These principles must be used as the basis for guidelines when exercising public authority, including when an administrative body allocates subsidies and when managing real property.

It is important to ensure that decisions about land use are made based on an up-to-date knowledge platform adapted for the plan or project. The regulations on impact assessments will contribute towards this. The central regulations on impact assessments in Norway can be found in the Norwegian Planning and Building Act and regulations on impact assessments. The regulations apply to plans and measures under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act and to individual plans and measures under other regulations, such as power lines under the Norwegian Energy Act. The purpose of the regulations is to ensure that considerations for the environment and society are taken into account in the preparation of plans and measures and when considering if and under which terms plans or measures can be implemented. The regulations include, among other things, provisions on what needs to be assessed and how, on what needs to be described and how to establish terms for mitigating measures (mitigation hierarchy) and on participation from affected stakeholders and the general public.

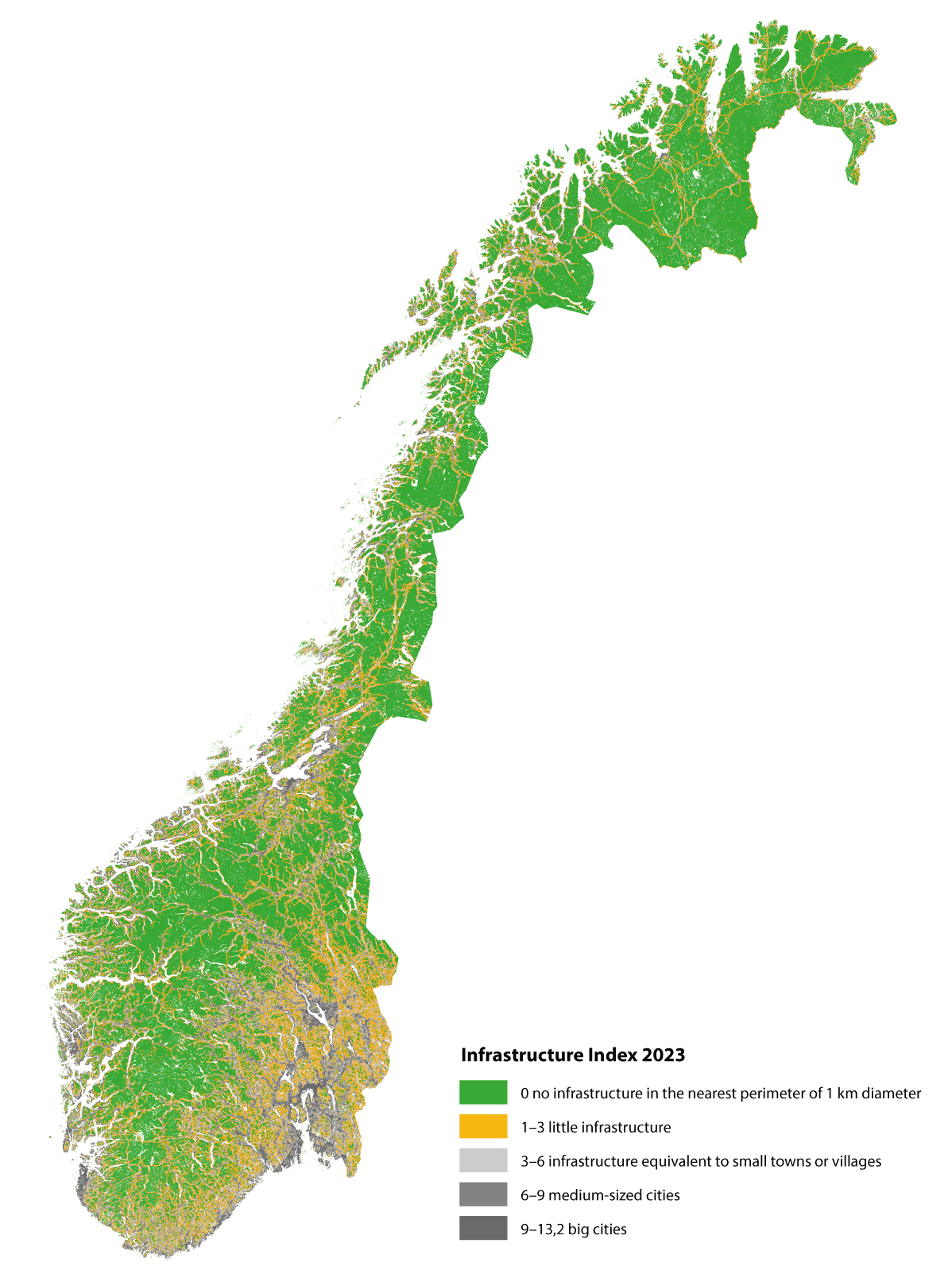

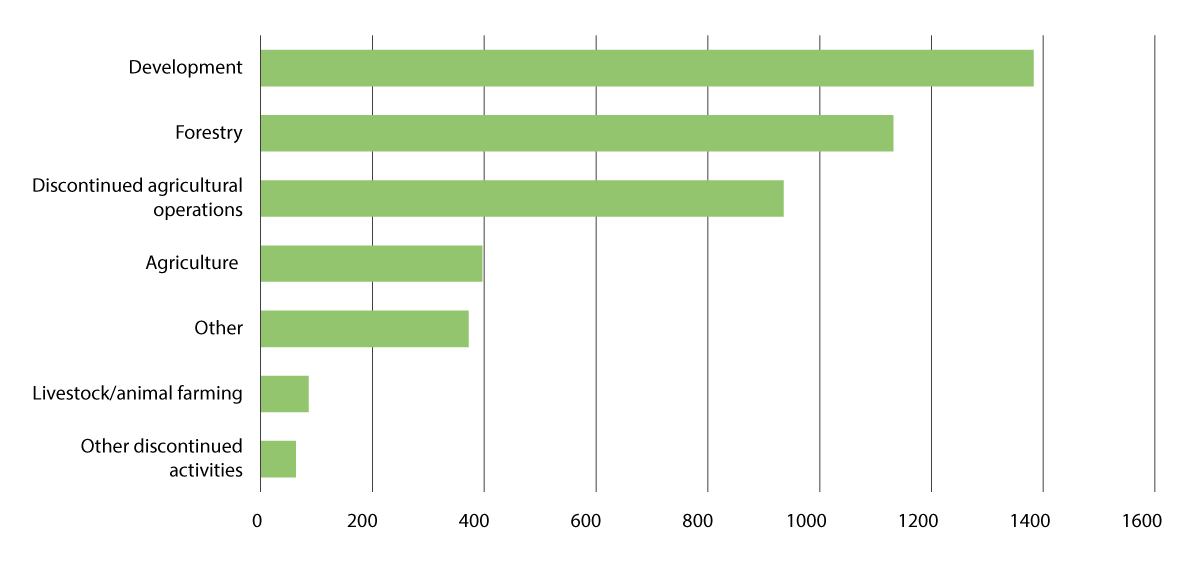

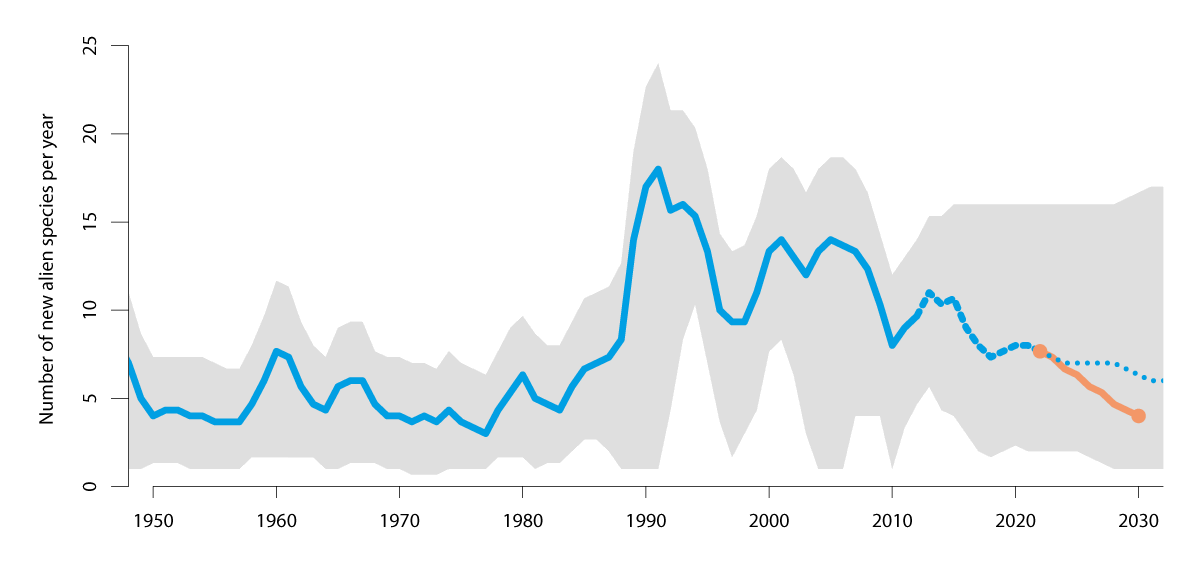

There is no comprehensive overview of how, or to what extent, biodiversity and climate have been taken into account in all local land use plans under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act. At the same time, the Norwegian Environment Agency estimates that the annual loss of natural land due to development projects will be between 35 and 40 km2 in the future1 and a compilation of data relating to planned development in plans under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act2 and other legislation3 created by the Norwegian Environment Agency shows that development projects totalling approximately 4000 km2 (1.2 per cent) are planned, of which approximately 90 per cent are currently classified as natural land. The Infrastructure Index quantifies the scope of man-made intervention in nature, such as buildings, roads and facilities, and shows that the greatest scope can be found in the regions of the country with the most species, see Figure 6.1 and Figure 3.1.4

Figure 6.1 Infrastructure Index

The Infrastructure Index shows land use intensity in Norway. The index is calculated based on the extent of different types of infrastructure (buildings, roads and facilities) within a radius of 500 metres around the analysis point at a distance of 100 metres from one another.

Source: Erikstad et al. (2023)

Both the Climate Commission 2050 and the Nature Risk Commission, which delivered their respective reports in autumn 2023 and winter 2024, have made recommendations relating to the management of land as a limited resource. The Climate Commission 2050 believes that land use policy must limit the loss of nature and contribute to the preservation of natural carbon stores and therefore recommends that development projects that lead to loss of natural land be limited significantly and that clearer and more binding national frameworks be established for land use, that the national conservation of ecosystems be increased, and that binding, comprehensive plans for ocean use be established. The committee points to a need to update laws and regulations to better reflect climate and nature considerations, including the Norwegian Planning and Building Act, the Norwegian Nature Diversity Act and the regulations on impact assessments. The need to further develop the systems for organisation and follow-up on land use policy and to strengthen knowledge and expertise to ensure sustainable land management is also highlighted by the committee.5 The Nature Risk Commission believes, among other things, that nature risk must be included in relevant decision-making processes and that clearer frameworks relating to the assessment of nature risk will result in better management, including land management, as land is a scarce resource. Furthermore, the committee believes that all levels of government should use nature risk assessments to make decisions in accordance with the precautionary principle and to gain an understanding of the overall impact and risk of potentially catastrophic outcomes.6

The Norwegian Planning and Building Act also safeguards the consideration of Sami rights. Section 3-1 of the Norwegian Planning and Building Act supplements the objective of the act and sets out the responsibilities and considerations that must be taken into account in planning. It follows from Section 3-1 c that one of the considerations is: «protect the natural basis for Sami culture, economic activity and social life» According to Chapter 4 of the Sami Act, the Sami Parliament and other affected Sami stakeholders have the right to be consulted on measures that relate directly to Sami interests.

Textbox 6.2 The Fosen case

On 11 October 2021, the Supreme Court rejected the case on the assessment of expropriation compensation for reindeer farmers in Fosen on the grounds that the licensing and expropriation decisions were invalid. The Supreme Court found that the wind power development would have a significant negative impact on the reindeer owners’ ability to practice their culture in Fosen. Furthermore, the Supreme Court also found that the mitigating measures set out in the license were inadequate in avoiding significant negative impact on reindeer husbandry in the region and that the decision therefore contravened Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CP). It is the responsibility of the state to safeguard rights under Article 27 of CP. The state also has a duty to ensure that any violation of the covenant be remedied and a number of different measures could therefore be relevant in achieving this. There may often be a need for the state to implement or impose measures, but the violation can also be remedied by establishing alternative solutions between affected private parties or through a combination of agreed resolutions and government measures. Minority participation in decision-making processes and consent for new measures or agreements will be an important factor in such assessments.

A mediation process was initiated in March 2023 and amicable agreements have now been entered into between the reindeer herders in the Fosen reindeer pasture district and the wind power enterprises. The Sør-Fosen reindeer herders and Fosen Vind reached an agreement on 18 December 2023, while the Nord-Fosen reindeer herders and Roan Vind reached an agreement on 6 March 2024. The agreements set out obligations both for the parties and for the state. The state will, among other things, obtain additional land outside the Fosen reindeer pasture district that can be used for winter pasture for both groups of reindeer herders. It is a prerequisite for the reindeer herders to consent to the use of the additional land and that the land meets the requirements set out in Section 8 of the Norwegian Reindeer Act. The goal is for the additional land to be available to reindeer herders during winter 2026/2027.

6.1.3 Measures and instruments to contribute to the target

Integrated and sustainable land-use management

Integrated and sustainable land-use management is essential for achieving several different societal targets and for striking an appropriate balance between different interests. Norway has already largely implemented the systems for integrated land-use management addressed in the global target. At the same time, natural land is a limited resource and there is a need to establish a clear direction of reducing development projects that lead to a loss of natural land going forward. The Government will therefore establish the following target:

Norway will reduce the number of development projects that contribute to loss of areas of especially high ecological integrity by 2030 and, by 2050, limit the net loss of such areas to a minimum. The target will be achieved through participatory, integrated and biodiversity-inclusive spatial planning that respects local governance and the rights of indigenous peoples.

This will be Norway’s National target to target 1 of the KMGBF. The target will form the basis for government activities and will serve as guidance for local authorities. The Government notes that especially important natural land includes biodiversity of national and significant regional interest, cf. the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment’s Circular T-2/16.7 The aim is not to reduce the opportunity to develop socially beneficial renewable power production and power lines. See the more detailed discussion in Chapter 5.4.1.

The Government further highlights five principles for sustainable land-use management that will contribute to societally favourable and effective land use. The principles clarify, among other things, the need to choose locations and development solutions that avoid negative impact on natural and agricultural land, limit impact that cannot be avoided and repair any direct impact after development. Compensation is the final resort to remedy loss of natural and agricultural land. The principles are presented in Chapter 5.4.2.

As referenced in Chapter 5.4, research and studies show that considerations related to climate and nature are not adequately taken into account in spatial planning and that large land reserves have been set aside for development purposes in the prevailing municipal master plans. There is a need for improved knowledge of development projects that lead to a loss of natural land, both with regard to where development projects are implemented and the ecosystems that are lost. The Government is working to establish national nature accounts, as well as contributing data and guidance for nature accounts at regional, local and project level. See further details under Local land and nature accounts below. Other work is addressed in Chapter 5.2.

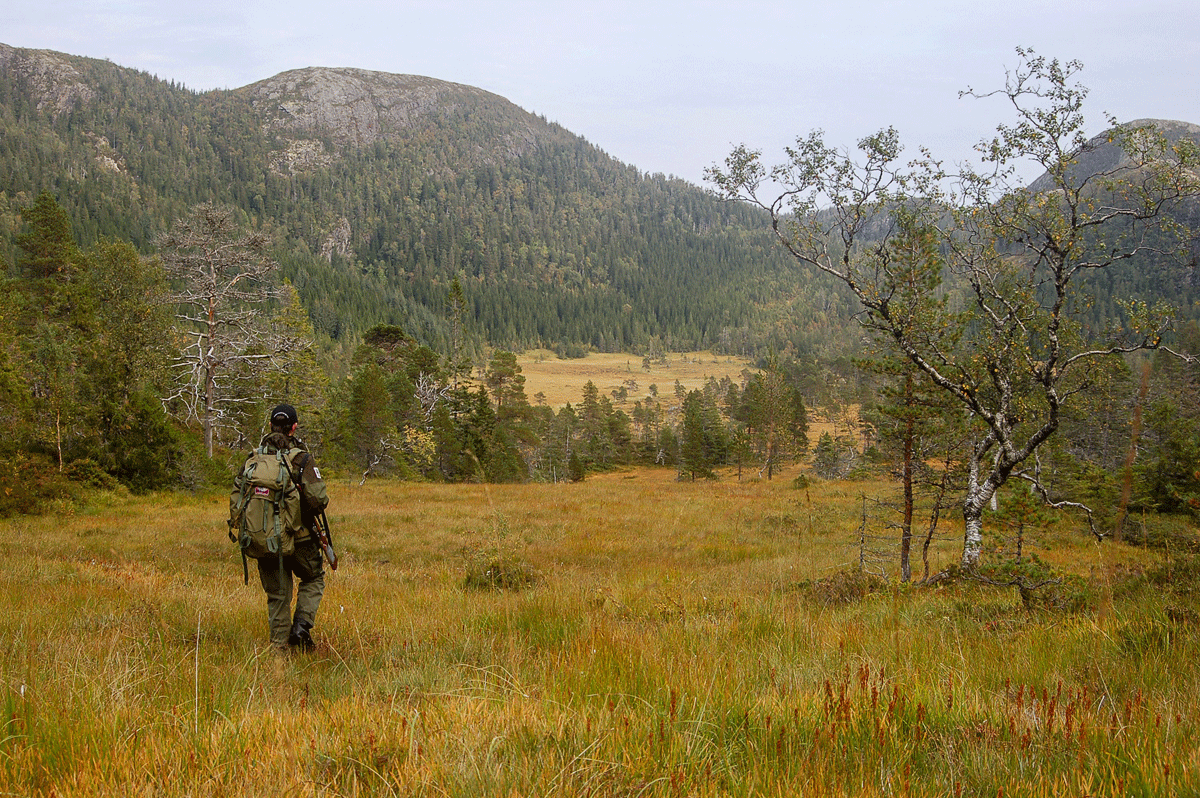

Sami reindeer husbandry is a land-intensive industry. Human activity and different types of intervention in reindeer pasture land create challenges, in addition to natural disruption from e.g. predatory animals. Pasture land is under growing pressure and increasing land interventions currently constitute one of the greatest threats to reindeer husbandry. The development of roads, hydropower, wind power, mining, etc. often takes place in areas that are currently classified as outfields and may result in decreased pasture for reindeer. In addition to direct land loss, reindeer will also migrate away from such installations to varying extents. Local authorities must take into account considerations related to reindeer husbandry in land-use management. This requires local authorities to have excellent knowledge platforms that include knowledge of reindeer husbandry traditions in order to balance the need for development and consideration of Sami interests. The Government presented a package of measures for reindeer husbandry and energy in 2023. The package of measures includes 24 measures that will, in combination, contribute to safeguarding the consideration of Sami reindeer husbandry in energy planning and development. Several of the measures will be relevant to planning and development in general.

Textbox 6.3 Onshore energy plants

Developing renewable energy production and grids requires land and cannot take place without impact on the environment and society, but the extent of the impact depends on the technology and location. An analysis for Norway shows that the affected land from damming in reservoirs is 2169 km2.1 Physical interventions relating to hydropower developments include dam facilities, construction roads, power stations, pipe trenches/development reaches, power plant wastewater, mass landfill and power lines. Hydropower affects species and their biotopes in and adjacent to lakes and rivers. Other impacts include hydrological and morphological changes, such as water level variations in reservoirs, reduced rate of flow in rivers, changed rate of flow throughout the year or between years, changes to ice conditions and reduced sediment transport.

For wind power, direct physical interventions of approximately 1.5 km2 per TWh of produced power have been calculated. At the same time, a larger area is affected, and the planning area is typically estimated to be 35 km2 per TWh. Today, the planning area of Norwegian wind power plants totals 587 km2.2 Subject to adequate light conditions, wind turbines can be visible across distances greater than 50 km, but the visual impact is often considered to be lower due to e.g. topography. Wind turbines can also affect nature through e.g. the collision risk for birds and movements and noises that may frighten wild animals (including wild reindeer) and domesticated reindeer. The road systems linked to wind power plants can, among other things, act as a barrier for wild animals and may lead to fragmentation of pasture land for reindeer.

Only a limited number of ground-mounted solar power plants has been developed in Norway. Published reports and applications show that a solar power plant with an installed capacity of 1 MWp3 occupies on average 10–13 decares of land. Converted to production under Norwegian conditions, ground-mounted solar power will occupy 13–15 km2 of land per TWh. Large parts of the land occupied are directly linked to land use for solar panels and the required distance between panels.

Other land use from power systems includes land used for power lines, where the cleared belt below the lines running through forests accounts for the greatest land intervention, alongside construction roads for developments. Power lines also pose risks to birds and may act as barriers for wildlife, including wild and domesticated reindeer.

The knowledge platform on habitat types and species has improved significantly in recent years, in no small part due to increased research. This constitutes important information that is used in licensing considerations for energy plants. Licenses are currently approved subject to a set of measures to remedy environmental impact. For wind power and power lines, remedial measures typically include the establishment of wildlife corridors, detailed location of turbines and roads to avoid bogs, marking of blades to avoid bird strike, radar-controlled lighting, bird deflectors on lines and adjustments to line profiles. Licenses for hydropower plants are, for example, granted subject to terms relating to the release of an ecological rate of flow, limitations on the use of reservoirs, location and design of different plant elements, construction of fish ladders and different habitat improvements. For existing plants with licenses subject to modern standard terms, subsequent investigations together with orders relating to remedial measures may contribute to reducing the negative impact.

1 Harby and Carolli (2022).

2 NVE (2022).

3 MWp describes the theoretical production capacity of solar panels under standard testing conditions. The actual capacity the plant can supply to the grid is specified in MW, which is normally somewhat lower than MWp.

Local authorities as key stakeholders

Local authorities have the main responsibility for spatial planning under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act. Through active use of land-use objectives, zones requiring special consideration and planning provisions in local plans, local authorities can contribute to effective land use that limits greenhouse gas emissions and safeguards national interests linked to biodiversity, cultural environments, landscapes and cultivated land. Proper spatial planning is important throughout the country. Central and regional agencies are responsible for participating in local planning processes and must produce information of significance to planning. Pursuant to Section 5-4 of the Norwegian Planning and Building Act, affected central and regional agencies have the opportunity to submit objections to plans that contradict national or significant regional interests and other key considerations. The Sami Parliament also has the opportunity to present objections on matters of significant importance to Sami culture or operations. In Circular T-2/16 National and significant regional interests within the environmental domain – clarification of the environmental authorities’ objection practices, the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment clarified what are considered matters of national or significant regional importance or that are otherwise of significant importance to the climate and environment, including biodiversity. The circular contributes to more integrated administrative practices and increased predictability in local spatial planning. The circular was last updated in February 2021.

In June 2023, the Government presented new National expectations for regional and local planning 2023–2027. Here, the Government communicates the most important national planning priorities under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act. Considerations related to biodiversity and climate were clarified in the national expectations of 2023. The Government encourages, among other things, local authorities to establish targets to reduce development projects that lead to a loss of land with the purpose of achieving the climate and environment targets. Furthermore, the Government also expects important biodiversity, agricultural land, aquatic environments, recreational areas, overarching green structures, cultural environments and landscapes to be mapped and safeguarded in planning and that the overall impact of existing and planned land use be weighted. In connection with revisions to the land-use element of the municipal master plan, local authorities should also consider whether previously approved land use should be reversed to agricultural, natural, recreational and reindeer husbandry purposes out of consideration for biodiversity. These, and other expectations, must be followed up in regional and local planning.

Several local authorities have adopted different local land neutrality targets. Land neutrality means that all physical loss of natural land is compensated for through the restoration of similar natural land. This is also referred to as biodiversity net zero. Local authorities have varying capacity to compensate loss of nature through reversal. For many local authorities, a land neutrality target will likely mean that future development projects that lead to loss of natural land need to be significantly reduced. Adequate local assessments must be carried out to establish whether or not such targets are appropriate.

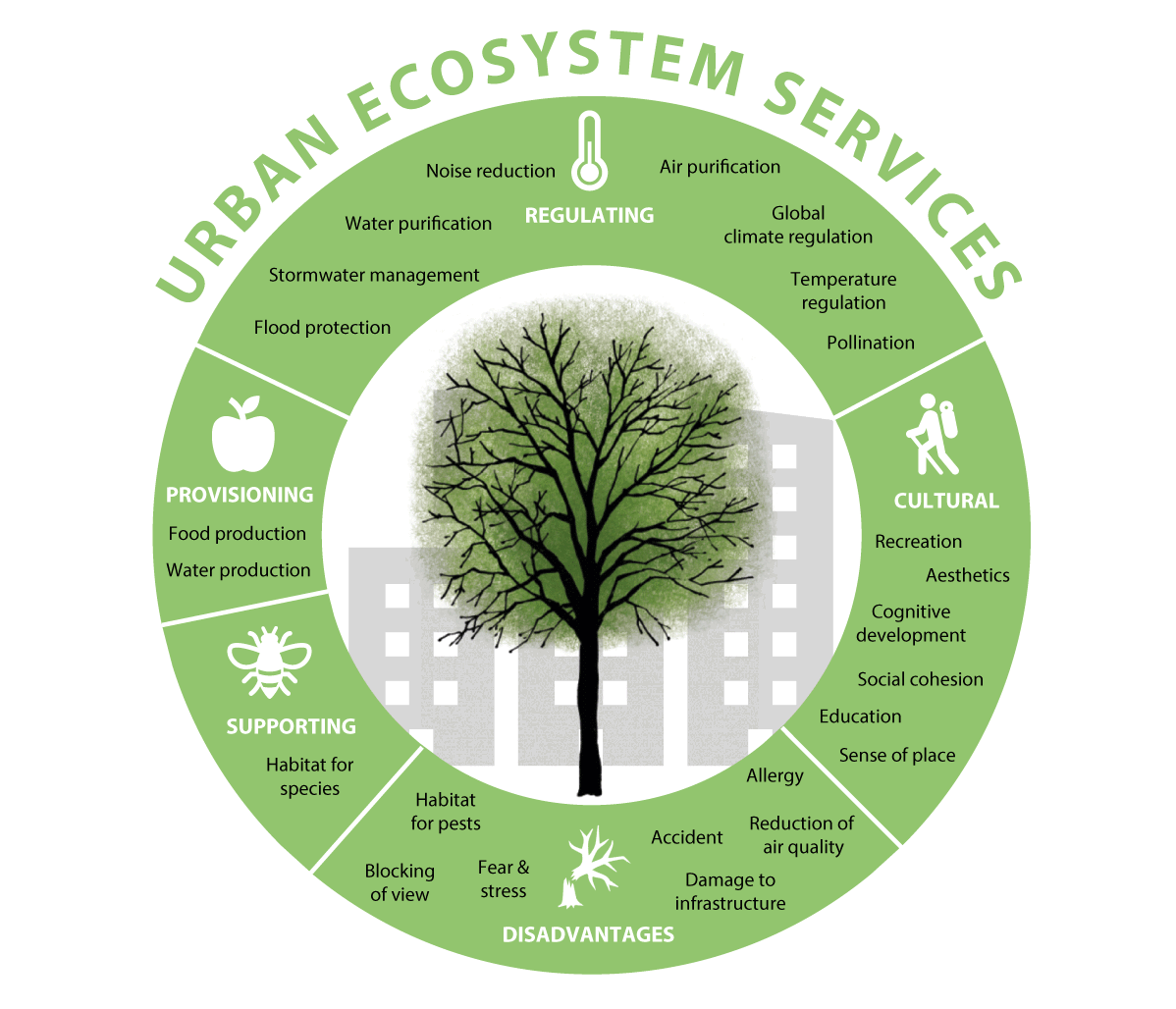

Local land and nature accounts

Many local authorities do not have an overview of actual land use or the characteristics of the areas that are being considered or proposed for reallocation for development purposes in the municipal master plan. The Government believes that local authorities should prepare land accounts as part of the knowledge platform for community and spatial planning. Land accounting can be a useful tool when local authorities revise municipal master plans and consider new and previously approved development areas and the overall impact from land use. The Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development has issued a guide on how local authorities can prepare and use land accounts in their work on municipal master plans and biodiversity is one of the themes addressed. Going forward, it would be natural for local land accounts to be combined with nature accounts that show the historical and current situations for different types of, as well as how much, land the local authority holds, the integrity of nature and the services it provides. The local authority would obtain a better overview of local biodiversity and the functions provided by nature, such as contributions to flood retention, landslide protection, water purification, carbon capture and storage, etc. Together, local land and nature accounts can help local authorities and other stakeholders in land management to assess the overall impact on ecosystems and whether planned land use will make ecosystems more or less resilient to climate change. Many local authorities are in the process of preparing land and nature accounts and are using these when revising their municipal master plans. Regional authorities have an important role to play in supporting and guiding local authorities in the work and in drawing up accounts that place land developments in the context of a larger region. The Norwegian Environment Agency develops guidance for local and regional nature accounts. The Government will facilitate the use of land and nature accounts at local level as part of the knowledge platform for spatial planning and as a tool in assessing the impact of future land use when requested by the local authorities.

As discussed in Chapter 5.2, NIBIO, Statistics Norway, the Norwegian Mapping Agency and the Norwegian Environment Agency have drawn up a base map for use in land accounts and nature accounts. An initial version was published in March 2024 and is now being tested.8 The Government will continue its work to establish a national base map for use in land accounts and nature accounts that will be regularly updated and made available to local authorities and other stakeholders in land management.

Government planning guidelines

Five government planning guidelines have been drawn up and provide different levels of guidance for climate and environmental considerations in local spatial planning. These are the five government planning guidelines for differentiated management of the shoreline along the ocean, for coordinated residential, land and transport planning, for climate and energy planning, the national guidelines for protected water systems, as well as for strengthening children’s and young people’s interests in planning. The Government submitted its proposal for new government planning guidelines for land use and mobility and for climate and energy planning and climate adaptations for consultation during spring 2024. These may replace the current guidelines for coordinated residential, land and transport planning and for climate and energy planning and climate adaptation.

The Government planning guidelines for land use and mobility follow up on national expectations and provide further guidelines to prevent the loss of cultivated land, natural, wild reindeer and recreational land and carbon-rich areas from development projects. In Sami reindeer pasture land, planning must take into account the land use requirements for reindeer husbandry. The principle of densification and transformation must be considered and should be exploited before new development zones are set aside and put into use and this applies to all development purposes. In regions with larger urban areas, access to green areas and natural land must also be emphasised. The guidelines encourage differentiated land management and do, to some degree, allow for scattered residential development in districts with low development pressures. For holiday homes, the Government proposes guidelines that state that it is important that holiday home neighbourhoods in mountains and outfields be restricted to ensure continuous natural, wild reindeer and recreational areas, cultural environments and key areas for agriculture, reindeer husbandry and other commercial activities. The impact of development projects on the landscape must be assessed and minimised. Furthermore, a guideline is proposed that emphasises consideration for especially important areas for recreation and biodiversity, as well as carbon-rich areas, so that the quality and capacity of ecosystem services, carbon storage and climate adaptation are maintained.

The Government planning guidelines for climate and energy will, among other things, contribute to Norway achieving the climate targets, the basis of existence and biodiversity being preserved for current and future generations and society and ecosystems being prepared and adapted for climate change. The proposed guidelines include directions as to how local authorities should establish climate targets and action plans and how emission cuts, energy and climate adaptations must be safeguarded in planning under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act. The guidelines state that considerations for climate, biodiversity and energy must be prioritised highly in sectoral work and considered in conjunction. According to the proposal, the reallocation and development projects that lead to loss of carbon-rich areas, including bogs, tidal marshes, other types of wetlands and forests must be avoided to the extent possible. Alternative locations must be considered, and the impact must be highlighted. The guidelines state that land and nature accounts are tools that should be considered.

Tools and knowledge

The Government has a goal of continuing and strengthening the role of local authorities in land management and will work to improve the expertise and capacity of local authorities as land managers. The Government carries out ongoing work to draw up and further develop guidelines for local planning. The Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development has drawn up system guidance on planning under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act and several thematic guidance documents, such as guidance on the planning of holiday homes and marine spatial planning. The Norwegian Environment Agency provides guidance on environmental considerations in planning, including on various themes within biodiversity. The Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development and the Norwegian Environment Agency collaborate on guidance and have jointly developed a series of webinars on climate and biodiversity in planning. The county municipalities and county commissioners are responsible for providing guidance and actively contributing to local planning processes. In order to support local authorities in their planning and work to safeguard biodiversity considerations, the Government will work to ensure that county commissioners, county municipalities and central government agencies offer early, comprehensive and coordinated guidance on environmental themes and other national targets relating to land-use and planning to local authorities.

The county municipalities are the regional planning authorities and advisors responsible for providing planning guidance to local authorities. Regional and inter-municipal plans are important tools for considering land-use and social development in conjunction across municipal borders. This is important for solving many environmental challenges. One example are the regional water management plans for the 2022–2027 period, including guidelines for land use that will help ensure that local authorities safeguard the aquatic environment. Another example are the seven regional plans for mountain regions with wild reindeer that are intended to safeguard the biotopes for wild reindeer in future and balance the use and conservation of areas. The plans delineate national wild reindeer zones from peripheral areas and include guidelines for land use in different zones. Regional coastal zone plans help us to consider the integrated management of ocean regions and the shoreline across municipal borders, while regional plans for coordinated residential, land and transport planning will ensure that development patterns and transport systems are considered together for larger regions. Collaboration on the content of regional and inter-municipal plans can contribute to strengthening the expertise in the local authorities concerned. The Government will support the role of the regional authority by giving a report on regional teams in county municipalities to relieve the local authorities of tasks by offering them specialist expertise with an emphasis on nature, climate, environment, soil protection and other themes in planning. Any use of the «task relief teams» in country municipalities will be voluntary. At the same time, the Government will also assess inter-municipal solutions to meet the same need.

Many local authorities assume responsibility for safeguarding biodiversity and other key social interests in planning. The exchange of experiences between local authorities can therefore also contribute to skills development. In collaboration with the National Assembly of the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities, country municipalities and county commissioners, the Government will facilitate local authority networks on biodiversity, climate, soil conservation and planning. The purpose is for the local authorities to learn from one another and provide mutual inspiration and support in their efforts to support biodiversity. The model may be expanded to include new areas if it is successful.

The Norwegian Planning and Building Act provides the starting point for local authorities in their work on community and land-use planning. In order to empower local authorities and their role in biodiversity management, the Government will examine potential changes to the Norwegian Planning and Building Act in order to strengthen biodiversity considerations. Such an assessment must be viewed in the context of the ongoing assessment of amendments to the Norwegian Planning and Building Act in order to strengthen climate considerations. The purpose of the assessment will be to clarify, improve and increase the local authorities’ legal freedom to act without changing the allocation of responsibility between central government and local authorities. The assessment will also build on the assumption that the Norwegian Planning and Building Act is a procedural act under which biodiversity is one of several national targets that local authorities have a responsibility to manage and the fact that local authorities must balance different considerations. The assessment will prioritise legal bases and tools requested by local authorities in their work on biodiversity. Ongoing work is carried out to improve the regulations on impact assessments. The Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment and the Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development have initiated work to revise the regulations, see more under target 14.

Decisions on land use must, among other things, be made on the basis of the public map data (DOK), which has been adapted for local authorities’ planning and building work. Local authorities may request that anyone who submits a planning proposal, impact assessment or application for measures under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act must obtain geodata if this is necessary to consider the proposal. Knowledge of biodiversity, including mapping, has been addressed in further detail under target 21.

In 2021, a grant scheme aimed at local authorities who want to create a separate municipal sector plan for biodiversity was established under the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment’s budget. This is a measure whereby local authorities identify natural assets of national, regional and local significance as part of the knowledge platform for land-use management. By drawing up a separate municipal sector plan for biodiversity, several local authorities have achieved increased knowledge and awareness of biodiversity in their municipality. The planning process also provides excellent opportunities to facilitate local participation, which is important for obtaining good input and local engagement in biodiversity work. Between 2016 and 2023, 82 local authorities have received grants to establish such plans. From 2024, the scheme has been expanded and is now referred to as «nature grants». Subsidies are also available to local authorities seeking to revise adopted municipal sector plans for biodiversity and to revise plans. This means that the local authority would revise older land use plans and assess these in line with updated knowledge about natural assets. Under the grant scheme, local authorities can also access funds to implement local measures to safeguard biodiversity. In 2024, a total of NOK 68 million has been set aside for the grant scheme and 45 local authorities have received funding to create municipal sector plans for biodiversity.

Svalbard

Currently, the contribution from land use changes to the loss of areas of significance to biodiversity and ecosystems with good ecological integrity is virtually zero on Svalbard. At the same time, the impact of climate change constitutes a threat to the natural environment, ecosystems and wildlife. The conservation of Svalbard’s unique wilderness is one of the overarching targets set out in Svalbard policy and the environmental protection targets for Svalbard state that the extent of wilderness must be maintained. Measures to ensure that the environmental targets are achieved have been described in White paper no. 26 (2023–2024) Svalbard.

Marine areas

The management plans for the Norwegian sea areas implement integrated, ecosystem-based management, by assessing the cumulative human impact on the marine environment, and by managing the use of the ocean in a way that allows ecosystems to maintain natural functions and service provision. The plans are updated every four years. The management plans include decisions relating to the framework for petroleum activities. The management plans provide clarity through overarching frameworks, coordination and priorities for the management of sea areas, and for the achievement of target 1 through broad involvement of government agencies. The management plans are discussed in further detail under target 14. The Government has also presented an Ocean Industry Plan for Norwegian sea areas, including ten overarching principles for marine area use, contributing to strengthened cross-sectoral coordination, increased predictability for users of the ocean and co-existence.

In 2020, Norway endorsed the recommendations from the Ocean Panel and has politically committed to the sustainable management of 100 per cent of the sea areas under national jurisdiction, based on Sustainable Ocean Plans, by 2025. The Ocean Panel has stated that a sustainable ocean plan is to include guidelines and mechanisms to facilitate a rich, vibrant and productive ocean for both current and future generations. Sustainable ocean plans will provide a framework to manage conflicts associated with marine area use and resources. They will facilitate long-term sustainable growth in the ocean economy. As a minimum, the Ocean Panel recommends that, as the basis for a sustainable ocean economy, plans must be drawn up and implemented through an inclusive, participatory, transparent and responsible process. The White paper no. 21 (2023–2024) Norway’s integrated ocean management plans will be translated into English and will be the mainstay of the Norwegian Sustainable Ocean Plan.

The Ocean Panel highlights the development of national ocean accounting as one of several measures to achieve the target of sustainable management of oceans and coasts. Ocean accounts are thematic accounts that collate data using three international accounting frameworks. One of these is nature accounts, together with frameworks for economic activity and the impact on the environment and use of natural resources. Work on nature accounting has been addressed in further detail in Chapter 5.2.

International follow-up

Through Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative, Norway works to contribute to sustainable land use policies in countries with tropical forests, see further details in Chapter 4.2. Since its inception in 2008, Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative has expanded its work to look at broader elements of land use management in tropical forest countries than just forest areas. The demand for agricultural products such as cattle and vegetable oil is one important cause of deforestation and land degradation. This means that the management of agricultural land in particular has an impact on the development of forest areas and the management of agricultural land is therefore included as part of the dialogue with several tropical forest countries. Work to protect mangroves is also a part of Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative’s efforts. Through Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative, Norway supports the efforts of tropical forest countries to achieve target 1.

The Government will:

Nationally:

-

facilitate the use of land and nature accounts at local and regional level as part of the knowledge platform for spatial planning and as a tool in assessing the impact of future land use

-

continue its work to establish a national base map for use in land accounts and nature accounts that will be regularly updated and made available to local authorities and other stakeholders in land management

-

strengthen the local authorities’ expertise and capacity in relation to eco-friendly planning by:

-

continuing and strengthening the role of local authorities in land management and working to improve the expertise and capacity of local authorities as land managers

-

assessing regional task relief teams or inter-authority solutions to meet the same needs in order to offer specialist expertise to local authorities with an emphasis on nature, climate, environment, soil conservation and other themes in planning

-

working to ensure that county governors, regional authorities and central government agencies offer early, comprehensive and coordinated guidance on environmental themes and other national targets relating to land and planning to local authorities

-

collaborating with the National Assembly of the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities, regional authorities and county commissioners to facilitate local authority networks on biodiversity, climate, soil conservation and planning

-

assessing potential amendments to the Norwegian Planning and Building Act in order to strengthen biodiversity considerations. Such an assessment must be viewed in relation to the ongoing assessment of amendments to the Norwegian Planning and Building Act in order to strengthen climate considerations. The purpose of the assessment is to clarify, prepare and strengthen the local authorities’ legal freedom to act without changing the allocation of responsibility between central and local government and to continue the assumption that the Norwegian Planning and Building Act is a procedural act under which local authorities must balance different considerations and follow up on several national targets.

-

Internationally:

-

strengthen Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative’s measures that contribute to conserved biodiversity by:

-

continuing to prioritise results-based partnerships with strategic tropical forest countries

-

further developing Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative’s efforts in other important forest ecosystems for biodiversity, such as savanna forests and mangrove forests through increased results-based support and programme support for such ecosystems

-

6.1.4 National target

Norwegian land is largely subject to spatial planning under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act and/or well-established administrative processes that facilitate participation. These regulations and processes include the balancing of all societal considerations, including biodiversity. There are challenges relating to adequate safeguarding of biodiversity and climate, as well as other environmental assets, in such processes. There is a need to establish a better overall overview of land lost due to development projects. Against this background, the Government has established the following objective for target 1:

By 2030, initiate actions to reduce the number of development projects that contribute to loss of areas of especially high ecological integrity, and by 2050, limit the net loss of such areas to a minimum. The implementation of the target will ensure an approach that secures participatory, integrated and biodiversity inclusive spatial planning, respecting local governance and the rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Especially important natural land includes biodiversity of national and significant regional interest, cf. the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment’s Circular T-2/16.

6.2 Target 2 – Restore Degraded Ecosystems

6.2.1 Global target

Ensure that by 2030 at least 30 per cent of areas of degraded terrestrial, inland water, and marine and coastal ecosystems are under effective restoration, in order to enhance biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services, ecological integrity and connectivity.

This target is linked to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, sub-goals 6.6, 14.2, 15.1 and 15.3.

6.2.2 Status in Norway

Nature restoration refers to measures that contribute to improving or restoring the integrity of ecosystems that have been degraded or destroyed. The goal is to ensure well-functioning ecosystems that deliver important ecosystem services. However, this does not mean that all measures that can contribute to positive developments in an ecosystem can be considered to constitute nature restoration. The measures must be of a certain significance and suitable for providing lasting effects. In many places, nature has been degraded or destroyed due to development projects, the introduction of alien species, pollution or unsustainable use without any action being taken to repair the damage. Through efforts to repair damage or restore nature in areas where nature has been degraded through earlier use, ecosystem status will improve and ecosystems will become more robust and resilient to climate change, provide important ecosystem services, such as stable carbon stores.

During the consideration of White paper no. 14 (2015–2016) Nature for Life, the Storting adopted request no. 669, which reads: «The Storting asks the Government to clarify what constitutes good status and what areas should be considered degraded ecosystems, and to escalate the work to improve the status of ecosystems with the aim of 15 per cent of degraded ecosystems being restored by 2025.» The Government responded to the request in the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment’s Prop. 1 S to the Storting (2022–2023). The response noted that an assessment system for ecological conditions has been developed and explained that degraded ecosystems can be assessed using this system. The Government also referenced efforts to establish menus of different measures to help maintain good ecological status in various ecosystems, that restoration measures will be considered alongside other environmental measures and that global targets for restoration will form the basis for the work.

The work to clarify the extent of areas in Norway that constitutes degraded ecosystems is not yet complete. The exception is the rivers and lakes ecosystem, as well as coastal waters, for which the specific bodies of water that are degraded have been determined through water management under the water regulations. The degradation of the ecosystems mountains, forests, oceans and Arctic tundra has been assessed at a general level based on the assessment system for ecological condition, but we do not have an overview of the specific areas that are degraded. For the ecosystems wetlands, semi-natural land and open lowlands, the overall integrity assessment will be carried out using the assessment system in 2026.

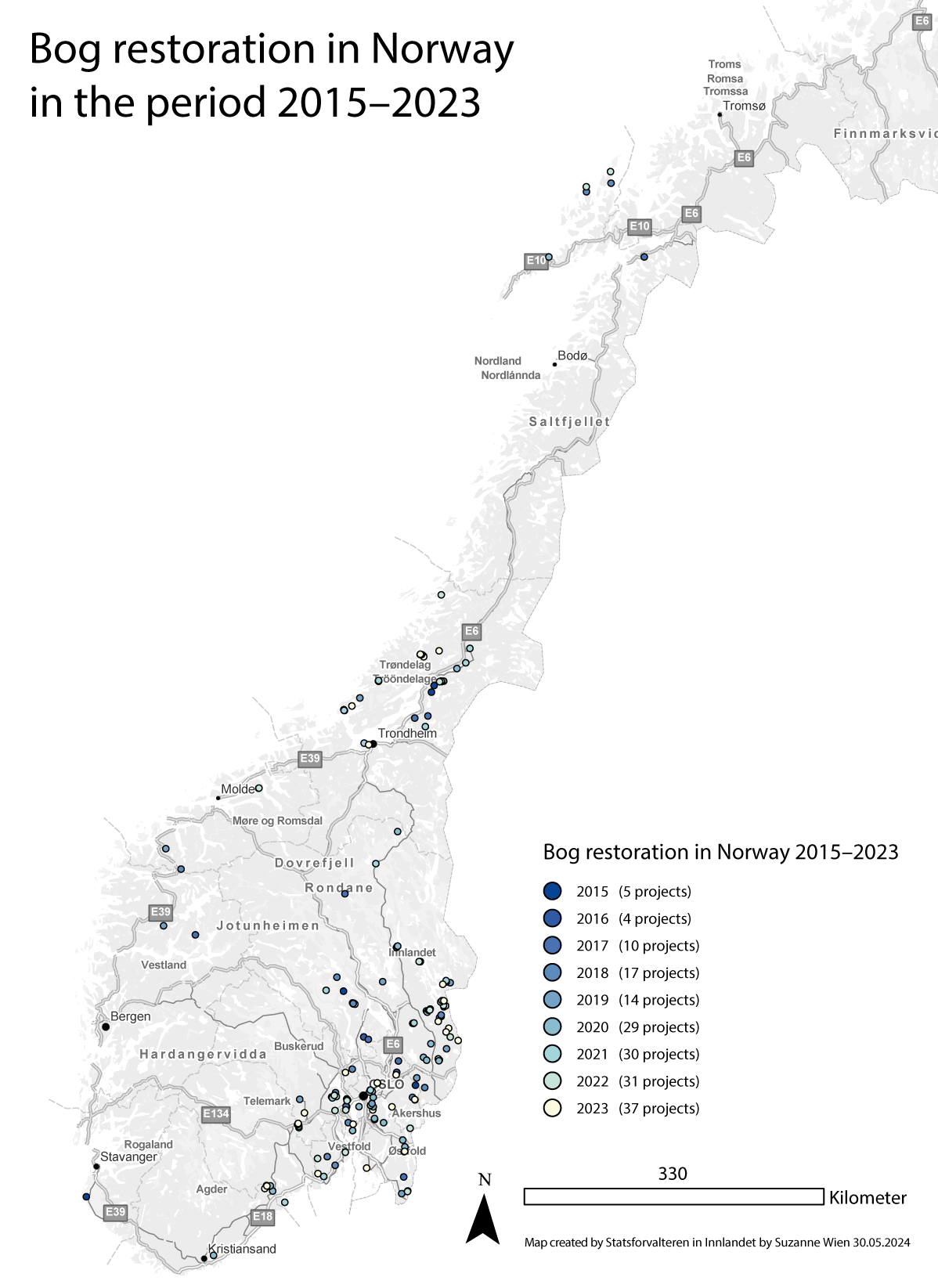

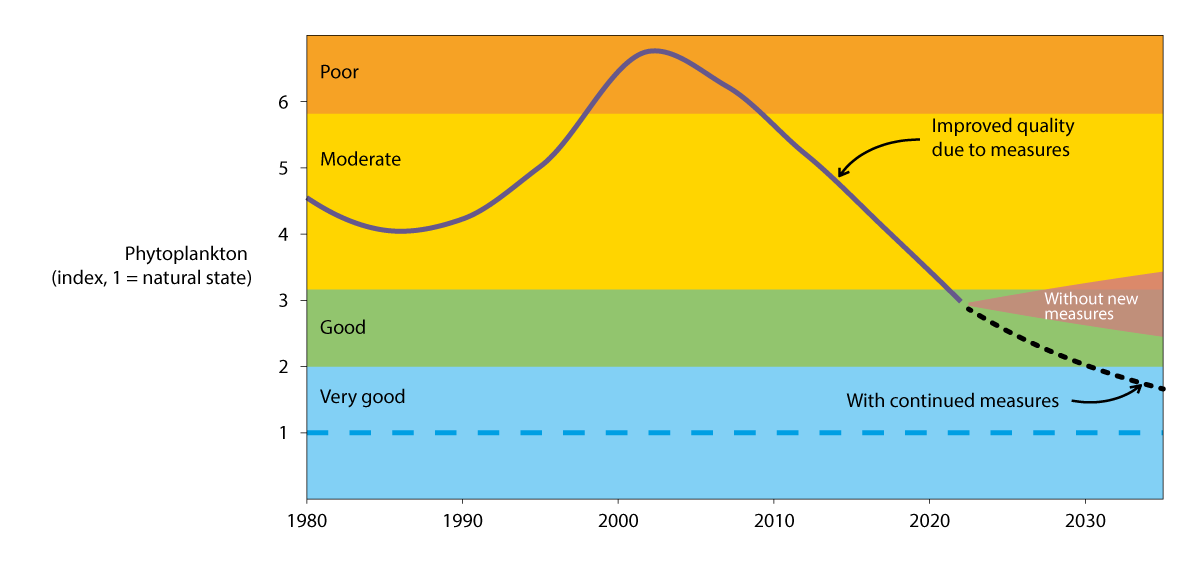

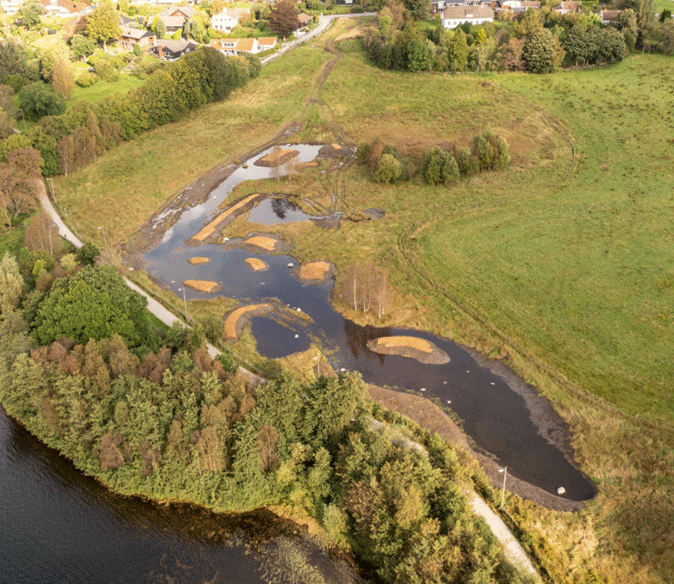

There is currently ongoing nature restoration work under way in several areas in Norway. A national strategy for the restoration of water systems has been established with a target of at least 15 per cent of degraded water systems in Norway to be restored during the 2021–2030 period. Since 2016, the Norwegian Environment Agency has restored wetlands in order to improve ecological status, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and contribute to better climate adaptation. The work is carried out in accordance with the prevailing Norwegian Wetland Restoration Plan 2021–2025. Since 2016, approximately 205 decares of peat extraction areas and around 190 bogs have been restored, totalling 9500 decares of bogland in which 456,000 metres of dikes have been closed (see Figure 6.2). Most of the measures have been carried out in protected areas, but increasingly also on land owned by Statskog, as well as on land owned by the municipalities and private parties.

Figure 6.2 Norwegian Bog Restoration 2015–2023

Bog restoration in Norway under the auspices of environmental management has so far largely taken place in Trøndelag and Eastern Norway.

Source: The Norwegian Environment Agency

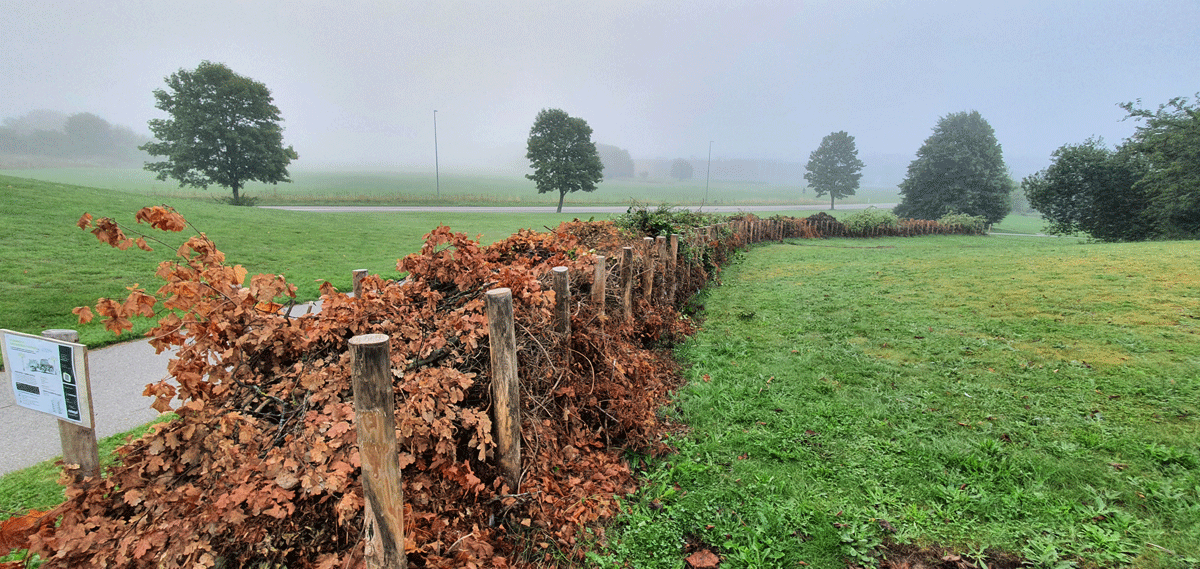

Restoration efforts are also under way in several other terrestrial ecosystems. In accordance with the management plan for endangered biodiversity, the habitats open areas on shallow lime-rich soils and sand dunes are also being restored. The biotopes hay fens and hay meadows and coastal heathlands are being restored through larger-scale measures at the start and will subsequently be maintained through annual care in the form of haying, grazing and heath scorching. Together with environmental funds and funding from the Agricultural Agreement, a total of around 1,000 hay meadows are now being managed. This corresponds to 8000–9000 decares. In forests, restoration efforts are taking place in conservation areas through the removal of alien species.

In marine areas, work is under way to restore marine ecosystems with a particular emphasis on the Skagerrak-Oslo Fjord region, with targets to restore the ecosystems’ production and biodiversity and capacity for natural carbon-binding and storage. Remediation of polluted seabed has also been carried out, and Pacific oysters are removed in Agder, Vestfold, Akershus, Oslo and Østfold.

In the Arctic, especially on Svalbard, the long history of conservation of species and regions of various types has resulted in the efficient restoration of many populations of mammals and birds that were previously in sharp decline due to over-exploitation. This has resulted in a long-term, large-scale restoration of wildlife and natural ecosystems on Svalbard and in the northern Barents Sea. The restoration of the mining areas at Svea on Svalbard also constitutes a significant contribution to the physical restoration of an industrial landscape back to near-original condition. The restoration efforts at Svea have increased the extent of wilderness areas on Svalbard by 118 km2.

Today, it is primarily government authorities such as the County Governor, the Norwegian Nature Inspectorate, the Norwegian Environment Agency and NVE that manage the planning of restoration efforts, while the practical implementation is carried out by private sector contractors. Some county municipalities and municipalities are also involved in the planning and implementation of nature restoration efforts.

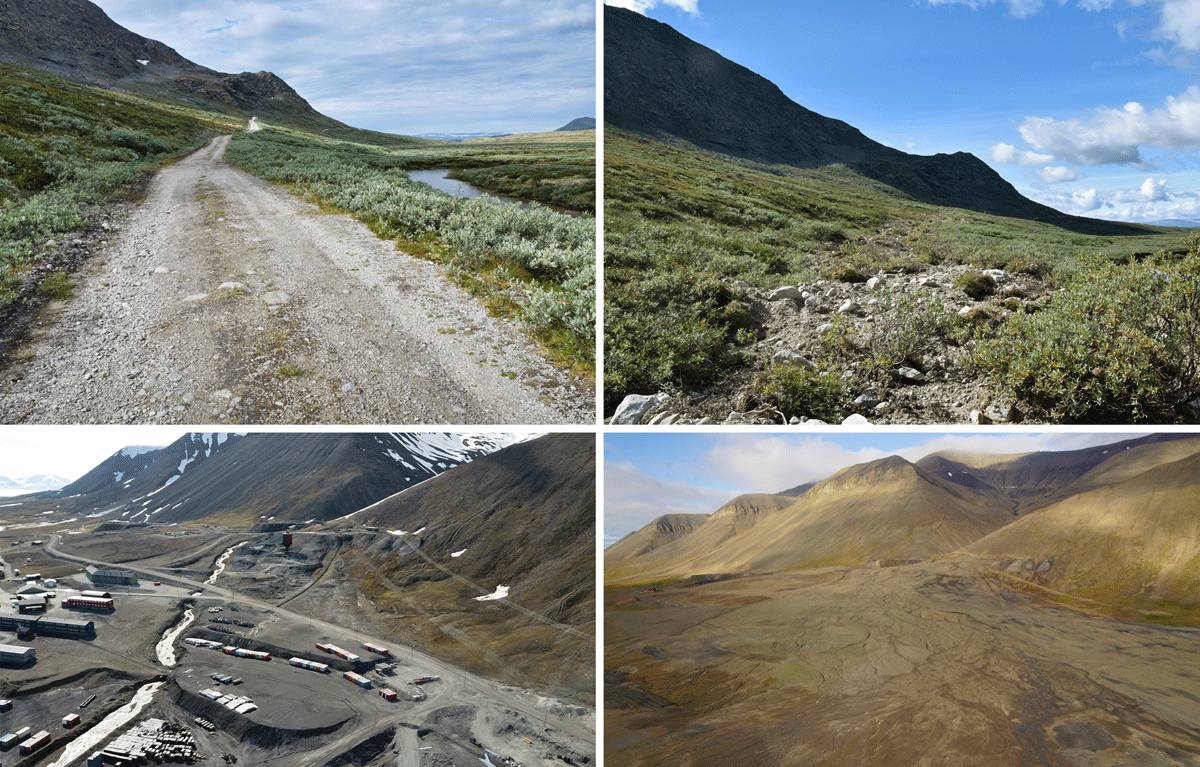

Textbox 6.4 Restoration of the Hjerkinn firing range and Svea mine

Two highly extensive restoration projects have been completed in Norway in recent years. These are significantly larger than other Norwegian restoration measures and demonstrate just what it is possible to achieve.

The restoration of nature at the former Hjerkinn firing range took place under the auspices of the defence sector and started in 2005 and was completed in 2020. A total of 5.2 km2 of nature was restored. The largest interventions at the firing range involved landfills, large, levelled plains used for military activities – including bomb training – and an extensive road network.

The firing range was situated in a rich nature area at Dovre, surrounded by national parks. The former firing range was granted protection in 2018. The majority – over 130 km2 – was protected as a national park and incorporated in the adjacent Dovrefjell-Sunndalsfjella National Park.

The reversal back to habitats for wild reindeer was an important condition for the restoration and has resulted in an increase equivalent to 12.2 km2 in high-quality summer habitat at the former firing range. The restoration is not only a biodiversity measure but also a climate measure. The storage potential at Hjerkinn is greatest at the restored willow moor and bog/wetlands. In total, the restored areas at Hjerkinn will have the capacity to store 54,500 tonnes of carbon.

On Svalbard, the restoration project at Svea and Lunckefjell is now complete following six years of work. An entire mining town with a mining history spanning nearly a century has been restored back to nature. The airport, dock facilities, oil tanks and a whole town’s worth of infrastructure have been cleared. In total, approximately 2 million m3 of mass have been moved, 42,000 m2 of buildings have been demolished and almost 30 km of road have been restored back to nature. All cultural heritage sites dating back to before 1946 are automatically preserved on Svalbard and this will be left behind as part of the landscape. Much of the restored areas have now been incorporated into Van Mijenfjorden National Park. The Governor of Svalbard has worked closely with the project owner, Store Norske, throughout the project and this has been key to the restoration being completed ahead of schedule and NOK 900 million below the original budget.

Figure 6.3 Before and after picture of the restoration at Hjerkinn (top) and Svea (bottom)

Photo: Dagmar Hagen/NINA and Store Norske

6.2.3 Measures and instruments to contribute to the target

Clarify the extent of degraded or destroyed nature

In order to succeed with nature restoration efforts, we need, among other things, an improved overview of areas with degraded or destroyed nature in Norway. In partnership with the affected sectoral authorities, the environmental management will clarify the extent of areas that are degraded or destroyed on land and in marine areas. The work will be based on relevant knowledge sources relating to the condition of Norwegian ecosystems. It will, for example, be relevant to use data from remote sensing, artificial intelligence (AI), the Norwegian Environment Agency’s mapping method for terrestrial habitat types and knowledge from work on the Menu of Measures for forests, etc. Work is also under way to develop nature accounts for Norway. As part of the latter, condition accounts will be drawn up to provide an overview of changes to condition of different ecosystems.

Targeted and effective restoration in ecosystem-based management

The overall restoration of nature should be targeted and effective so that the implementation of measures is prioritised in the areas where it provides the greatest benefits to society. This is best achieved by considering the need for restoration measures within a comprehensive ecosystem-based management process in which all relevant measures to achieve good condition in ecosystems are viewed in context. For the ecosystems forests, mountains and cultural landscapes and open lowlands, restoration measures are therefore considered as part of the Government’s work on the Menu of Measures. For the wetland ecosystem, the existing restoration plan has been incorporated into the Norwegian Nature Strategy for Wetlands. For rivers, lakes and coastal waters, similar considerations are carried out as part of the water management plans, while restoration in ocean regions is considered as part of the work on the management plans for marine areas.

Clarifying the allocation of responsibilities and strengthening the implementation of nature restoration measures

There is a need to strengthen capacity and expertise and ensure efficient organisation of both the planning and the implementation of measures. The involvement of government environmental authorities was important for gathering experiences and achieving successful results as the work on the restoration of bogs and other wetlands started, as well as in the work to remove alien tree species from protected areas. In order to increase efforts on nature restoration, the Government will ensure that more stakeholders outside of nature management are involved, such as municipalities, other government agencies, organisations, research institutions and private sector. Restoration helps improve the condition of nature, which is especially important for district municipalities where nature forms the basis for jobs in connection with e.g. agriculture, cabins and tourism. The work with nature restoration measures will also lead to jobs for local contractors. It is therefore important to accommodate local authorities’ and private parties’ integral involvement in nature restoration work, especially in the districts.

The state has limited instruments available to order or implement restoration measures outside of Svalbard, outside protected areas and in areas that are not degraded as a result of pollution. The Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment has therefore asked the Norwegian Environment Agency to review the existing – and the need for any new – legal instruments to increase the extent of nature restoration in Norway.

Based on the experiences so far and the need to ensure broader participation through increased efforts on restoration work, the Government bases the further work on nature restoration on the following:

-

The Norwegian Environment Agency has the overarching responsibility for nature restoration work in Norway. As part of this, the Norwegian Environment Agency will ensure that there is adequate coordination between the different authorities, provide guidance and develop and share updated knowledge of effective restoration methods for different ecosystems. The Norwegian Environment Agency will also maintain an overview of the extent of degraded and destroyed nature and completed restoration projects. The latter must be viewed in the context of the work on nature accounts.

-

Environmental management is responsible for the planning and implementation of restoration measures for degraded nature in protected areas.

-

Like today, the sectoral authorities will be responsible for the restoration of nature within their areas of responsibility.

-

Similarly, project owners, both public and private, will still be responsible for ensuring that measures are taken to avoid, limit, repair and – as the final resort – compensate for any loss of nature when it is necessary to carry out development projects that lead to loss of nature (mitigation hierarchy). This includes any restoration measures.

-

The local authorities’ roles and responsibilities in restoration work must be clarified.

-

Landowners, organisations, forest owner associations, Sami institutions and others are invited to contribute to restoration work through the use of grant schemes and by providing knowledge.

Grant schemes

In 2024, the Government launched a new nature restoration grant scheme aimed at municipalities, organisations and private project owners. The grant scheme will contribute to the restoration of degraded nature. Grants can be awarded for specific restoration measures, planning and monitoring of restoration measures, as well as nature-based solutions, see more under target 8. Furthermore, grants for special environmental measures in agriculture (SMIL) can also contribute to restoration measures, such as the establishment of riparian zones/environmental planting or the reopening of streams. Contributions from the grant schemes for measures in selected agricultural landscapes and the agricultural world heritage initiative can also be used for restoration and management initiatives. Through these grant schemes, the Government lays the foundations for stakeholders to also contribute to restoration work in the future.

The grant scheme to safeguard biodiversity in municipal planning, which has been discussed in further detail under target 1, is also relevant for nature restoration work. In the work on municipal sector plans for biodiversity, local authorities can gain an overview of the areas that include degraded ecosystems and plan and implement measures to improve integrity. In order to facilitate the work of the municipalities, the Government will draw up guidance on how the potential for restoration of nature can be assessed as part of this work. Guidance will also be drawn up on how areas that can be restored and have been restored can be protected in the land-use element of municipal master plans.

Action plans and other processes

The regional water management plans for 2021–2027 and associated action programmes include more than 12,000 measures, of which around 1600 are physical restoration measures. Restoration measures will, among other things, improve migration and distribution routes, physical conditions and water quality. If all the measures are implemented, the environmental targets can be achieved for around 90 per cent of bodies of water by 2027. The grant scheme for aquatic environment initiatives has supported 239 projects in the last three years. Furthermore, NVE’s budget for the grant schemes for flooding and landslide prevention, including environmental measures in water systems, has been increased.9 These grant schemes have funded large and small restoration projects and environmental improvement measures in and along water systems, as well as flood and landslide protection measures. In accordance with the strategy for the restoration of water systems, the action plan for the restoration of water systems is currently in development and will be regularly updated towards 2030. The plan will present specific recommendations on the prioritisation of individual water systems for comprehensive restoration. It will act as an important instrument to improve the ecological condition in bodies of water. The implementation will necessitate prioritisation and strengthened efforts. The work on the implementation of the Plan for the restoration of wetlands in Norway (2021–2025) forms the basis for continued restoration work in bogs and other wetlands. The restoration of bogs and wetlands is of great importance for restoring natural carbon stores and for climate adaptation.

A targeted restoration of the habitats for wild reindeer was one of five strategic areas presented by the Government in Report to the Storting no. 18 (2023–2024) Improved conditions for wild reindeer. Restoration will be an important measure in facilitating increased exchange of wild reindeer between wild reindeer zones and for wild reindeer to be able to move more freely within the wild reindeer zones that are currently established. Work on the restoration of nature in wild reindeer zones and adjacent areas that are or may become important to wild reindeer will initially be prioritised when action plans are drawn up in accordance with the quality standards for wild reindeer. These are plans that will be drawn up for each wild reindeer zone, with the aim of raising quality in these areas. The plan is that the first action plans will be issued for consultation in 2024/2025. The aim is to evaluate the impact of the action plans by 2030.

Restoration of marine biodiversity in marine and coastal areas, can be carried out through active restoration and passive measures to restore or improve the integrity of marine ecosystems. Natural restoration and recolonisation in selected conservation areas on a larger scale in suitable locations can strengthen ecosystems and provide space and time for ecosystems to naturally adapt. There is ongoing work to establish a pilot project in connection with one or more of the national parks in the Skagerrak-Oslo Fjord area, in order to restore ecosystems and develop knowledge of the impact of such measures.

The Government is working on an all-out effort for the Oslo Fjord to restore good ecological condition in the fjord, with a particular focus on the greatest impact factors: wastewater, agriculture and fishing. The Government actively monitors the Comprehensive Action Plan for a Clean and Rich Oslo Fjord with Active Outdoor Life, which in itself is a large-scale restoration project that entails several specific restoration measures and a number of environmental improvement measures. One of the targets set out in the action plan is the restoration of important natural assets. The action plan includes 63 specific measures and 19 items relating to knowledge collection for the purpose of increasing knowledge of the integrity of the fjord and how it can be improved, see box 6.11.

In Report to the Storting no. 14 (2006–2007) Together for a non-toxic environment – prerequisites for a safer future, 17 coastal and port areas were prioritised for the remediation of polluted seabeds. These are areas where particularly high levels of contamination have been identified, as well as an unacceptable risk of adverse impact on aquatic animals and plants, as well as health. Remediation measures are under way in Hammerfest and Bergen (Store Lungegårdsvann). Remediation measures have been completed in Oslo, Tromsø, Harstad, Trondheim and Sandefjord. Remediation measures have also been carried out in parts of Arendal, Kristiansand, Bergen (Puddefjorden), Stavanger (Bangavågen) and the Lister Fjords (Farsund and Flekkefjord).

International follow-up

Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative works to support countries with tropical forests to reduce deforestation and forest degradation. Through holistic, sustainable land use policies, partner countries obtain the basis needed to identify prioritised ecosystems and areas for restoration. The restoration of degraded forests and other degraded lands, such as wetlands, is part of Norway’s dialogue with partner countries on the follow-up to the KMGBF.

The Government will:

Nationally:

-

by 2030, clarify the extent of degraded or destroyed areas on land and in coastal and ocean regions based on existing knowledge of the condition of Norwegian nature and using new knowledge and technologies

-

consider targeted and effective measures for the restoration of nature in the work on the menus of measures, Nature Strategy for Wetlands and management plans for water and ocean regions.

-

follow up on the action plan for the Oslo Fjord

-

facilitate local authorities’ contributions to nature restoration as the planning authority and local environmental authority through guidance and existing grant schemes and by considering measures to strengthen the local authorities’ expertise and capacity in nature restoration work

-

evaluate the grant schemes for the restoration of nature

Internationally:

-

continue to facilitate the restoration of degraded ecosystems through Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative

6.2.4 National target

The restoration of nature helps reduce pressure on nature and maintain ecosystem services. The first step is to clarify the extent of degraded areas. Against this background, the Government has established the following objective for target 2:

By 2030, document the extent of degraded and destroyed natural areas in Norway, and restoration initiatives have been strengthened and implemented in areas where co-benefits for society at large is deemed highest.

6.3 Target 3 – Conserve Land, Waters and Seas

6.3.1 Global target

Ensure and enable that by 2030 at least 30 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas, and of marine and coastal areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services, are effectively conserved and managed through ecologically representative, well-connected and equitably governed systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, recognizing indigenous and traditional territories, where applicable, and integrated into wider landscapes, seascapes and the ocean, while ensuring that any sustainable use, where appropriate in such areas, is fully consistent with conservation outcomes, recognizing and respecting the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities, including over their traditional territories.

The target is linked to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, sub-goals 6.6, 11.4, 14.4, 14.5 and 15.4.

6.3.2 Status in Norway

According to the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the safeguarding of biodiversity and ecosystem services globally requires us to conserve 30–50 per cent of land, waters and seas through conservation and other effective area-based conservation measures. The global target is based on research10 that shows that by conserving at least 30 per cent of the land and ocean areas that are most important to biodiversity, we can ensure survival of more than 80 per cent of the species on land.11 Sustainable management contributes to maintaining the function of and biological production in ecosystems. In this context, the work within the sectors to help safeguard biodiversity under sectoral legislation and land and ocean management under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act will be important, alongside area conservation under environmental legislation and other effective area-specific conservation measures. Protection provides long-term, cross-sectoral protection of the natural values in the protected areas and constitutes an important instrument in safeguarding endangered species and habitat types. For species with a wide geographical range protected areas alone will not be sufficient and needs to be supplemented using other measures within the range. Statutory protection can currently be adopted under the Nature Diversity Act, the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act, the Jan Mayen Act and the Act relating to the Bouvet Island, Peter I’s Island and Queen Maud Land.

Norway is a member of the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (the Ocean Panel) and the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment in the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR), which have set equivalent targets to conserve marine biodiversity by 2030 to the global targets set out in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Status of areas that are protected or subject to long-term conservation using other measures

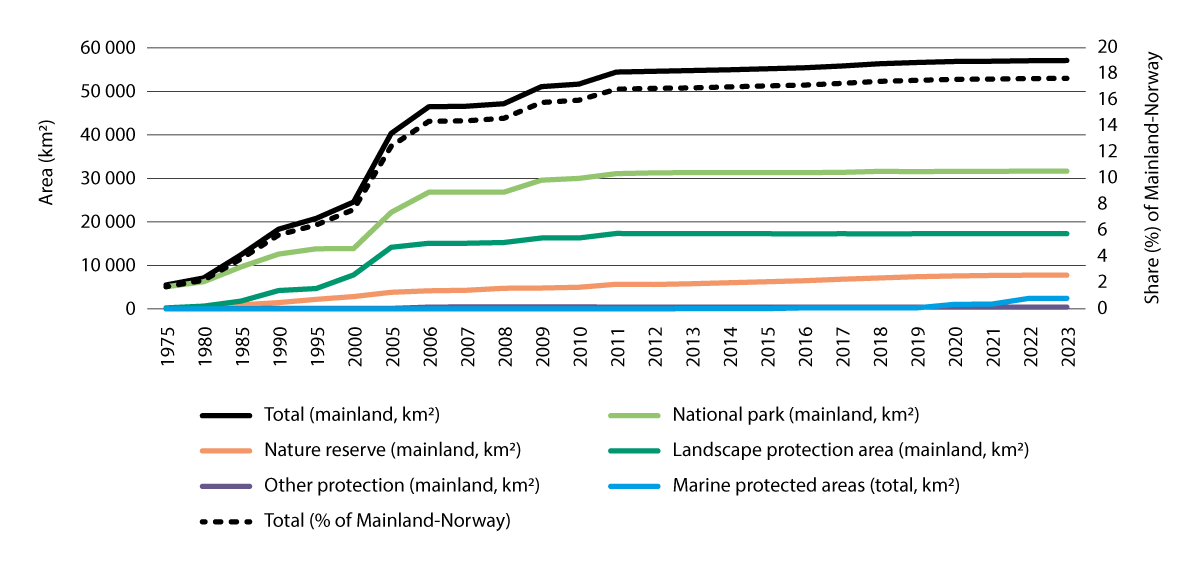

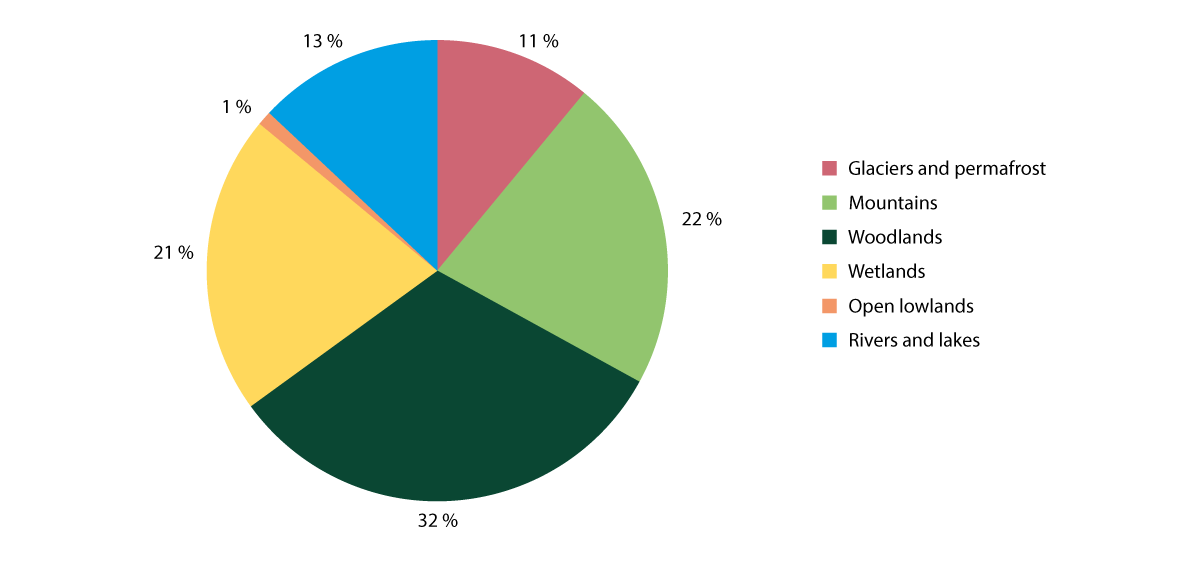

Norway has worked extensively to conserve a selection of all types habitats through statutory protection of areas. To date, Norway has classified approximately 25.7 per cent of its land area, including Svalbard and Jan Mayen, as protected areas. Disaggregated, this is approximately 17.7 per cent of mainland Norway (see Figure 6.4) and 69.1 per cent of the land area on Svalbard and Jan Mayen. We have also protected a total of 4.2. per cent of Norwegian marine areas under the Nature Diversity Act, the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act, the Jan Mayen Act and the Act relating to the Bouvet Island, Peter I’s Island and Queen Maud Land.

Today, 5.3 per cent of all forests and 4 per cent of productive forests are statutory protected. Furthermore, we have protected 14 per cent of rivers and lakes, 16 per cent of wetlands, 12 per cent of cultural landscapes and open lowlands and 34 per cent of mountain ecosystems.12

Figure 6.4 Areas protected under the Nature Diversity Act by protection category

The line for the total area does not include marine protection areas and includes mainland areas only. For marine protection areas, the total area is specified. A total of around 4.5 per cent of territorial waters adjacent to mainland Norway currently is statutory protected, of which the protection category marine protected areas account for 1.6 per cent. Figures as of 31 December 2023.

Source: The Norwegian Environment Agency and Statistics Norway

Processes are under way to better safeguard endangered species and habitat types and to ensure that protection areas are more representative, so that the width of Norwegian biodiversity is covered by protection areas and all types of nature habitats have protected locations.

The Storting decided as part of the consideration of the White paper no. 14 (2015–2016) Nature for life that 10 per cent of forests shall be statutory protected. The process to achieve this target is ongoing and new areas are assigned protection on an ongoing basis. The annual scope of new forest protection areas depends on the Storting’s annual allocation for forest protection. In the conservation of forests on private land, the voluntary protection principle applies. Voluntary forest protection is a scheme in which forest owners offer up forests for protection. If the area has biodiversity and environmental qualities that indicate conservation and the conservation authorities accept the offer, the area can be assigned protection status as a nature reserve pursuant to Section 37 of the Nature Diversity Act. An agreement will be negotiated between the forest owner and the state, which will include delimitation of the area, regulations governing the use of the area and compensation.

Furthermore, a process is also under way to protect smaller areas with valuable biodiversity in lowlands. Based on the areas identified by the Norwegian Environment Agency as relevant for such protection, this process will include up to 600 km2. Processes are also under way to assess the expansion of natural parks and landscape protection areas, as well as to establish new areas if applicable. There is no accurate estimate as to how large an area this might account for. It is assumed that the latter processes will take place only subject to local authority acceptance.

An increase in forest protection from the current 5.3 per cent to 10 per cent is expected to cover 5700 km2 and, together with the protection of smaller areas of valuable biodiversity in the lowlands, will contribute to increasing the protection share for Norway, including Svalbard and Jan Mayen, by approximately 2 percentage points.