5 Managing biodiversity for future welfare

Norwegian biodiversity is fundamental to the country’s creation of economic value, society’s ability to manage climate change, our mental and physical health and our ability to live good lives throughout the entire country.

The Storting endorsed the national biodiversity targets in white paper no. 14 (2015–2016) Nature for Life – Norwegian Biodiversity Action Plan, in which one of the targets is ecosystems with good status that provide ecosystem services. Norway has a rich biodiversity and Norwegian biodiversity management is, from a global perspective, well-developed and well-functioning. Nevertheless, we also experience challenges linked to loss and deterioration of biodiversity in Norway, see further details in Chapter 3. Land use changes constitute the greatest negative impact on Norwegian biodiversity on land.1 In the oceans, biodiversity is under increasing pressure from human activities, climate change and ocean acidification.

This white paper on biodiversity sets out how Norway will follow up on the global Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and thereby contribute to remedying the global challenges associated with loss of biodiversity. It also responds to how we can take the necessary steps to manage national challenges and needs to reduce loss and deterioration of biodiversity and ensure continued and sustainable use of biodiversity in Norway so that nature can continue to form the basis for creation of economic value and welfare in the future.

This chapter presents actions and instruments from the Government’s biodiversity policy that contribute towards the global targets. Please refer to Chapter 6 for further clarification of Norway’s contributions to each of the targets set out in the KMGBF.

Local authorities play a key role in the work on the conservation and sustainable use of nature, including through land-use management in accordance with the Norwegian Planning and Building Act. The National Assembly of the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities has indicated that the local and regional authority sector will take joint responsibility with central government to achieve the UN KMGBF targets.2 The autonomy of local and regional authorities is strong in Norway, and this is not affected by the proposals set out in this report. We achieve the best biodiversity management when local and regional authorities make the right choices in relation to biodiversity. Several of the proposals set out in the report will contribute the knowledge and tools needed by local and regional authorities to achieve this.

5.1 Regular Reviews of status, actions and target attainment

In Norway, extensive work has been undertaken to reduce loss and deterioration of biodiversity and ensure continued and sustainable use thereof. Nevertheless, we do experience challenges associated with the loss of biodiversity. The Government has systematised its work on climate change. Now, the Government is seeking to establish more systematic and integrated management of nature and Regular Reviews of the status, actions and target attainment will be key to this work. At the same time, tools are being developed and will be integrated at all administrative levels, and these will contribute to better decisions being made in relation to biodiversity. The local and regional authorities have an important role to play in identifying solutions and making good decisions based on comprehensive and up-to-date knowledge platforms.

Sustainable management of biodiversity should be based on knowledge relating to the integrity of ecosystems, the overall burden of human activity across sectors and the benefits of such activity. This will be in line with the principle of ecosystem-based management, which forms the basis for Norwegian biodiversity management and contributes to both the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.

Systems have already been established for comprehensive, targeted and cyclical management of ocean regions through the ocean management plans3 and for rivers and lakes and coastal waters through the water management plans4. A biodiversity strategy has also been established for wetlands. Through these plans, the overall integrity, impact and actions will be regularly assessed. The Government will also facilitate more integrated management of other aspects of biodiversity in line with the principle of ecosystem-based management through regular assessments of status, actions and target attainment. The Government has already made strides in this direction through the work that has been initiated on menus of measures for different ecosystems on land (see Chapter 5.3) and the development of national nature accounts (see Chapter 5.2). In working on the menus of measures, the Government will consider actions that help maintain a diversity of ecosystems with good ecological integrity. The nature accounts will provide an overview of the ecosystems’ dispersion, integrity and the ecosystem services they provide to society and will also contribute to an improved knowledge platform when decisions are made on the management of biodiversity going forward.

In order to better understand the context and coordinate the efforts for sustainable use and conservation of biodiversity across sectors, the Government will regularly – every four years – present an overview of the status, target attainment and actions implemented to the Storting via the Norwegian Biodiversity Action Plan. The overview will, among other things, be based on the processes established in connection with the Menu of Measures and nature accounts. The Regular Reviews will provide the basis for more accurate and continuous efforts to improve biodiversity management and attain the established targets. It may also be necessary to adjust the targets, for example on the basis of new knowledge. The work on conservation and sustainable use of nature will therefore be broadly endorsed and provides room for long-term thinking in biodiversity policies.

The Regular Reviews will contribute to the coordination of the efforts for sustainable use and conservation of biodiversity between different sectors. Meanwihle, sectoral responsibilities and instruments and the allocation of responsibilities between different levels of authority will remain unchanged.

The system of dedicated water and ocean management plans will also assess status, actions and target attainment on a regular basis, every sixth and every fourth year respectively. This remains unchanged. A summary of the status, targets and actions for these ecosystems, as established through the water management plans and ocean management plans respectively will be included in the overview presented to the Storting every four years so that it provides a comprehensive overview of all Norwegian biodiversity management.

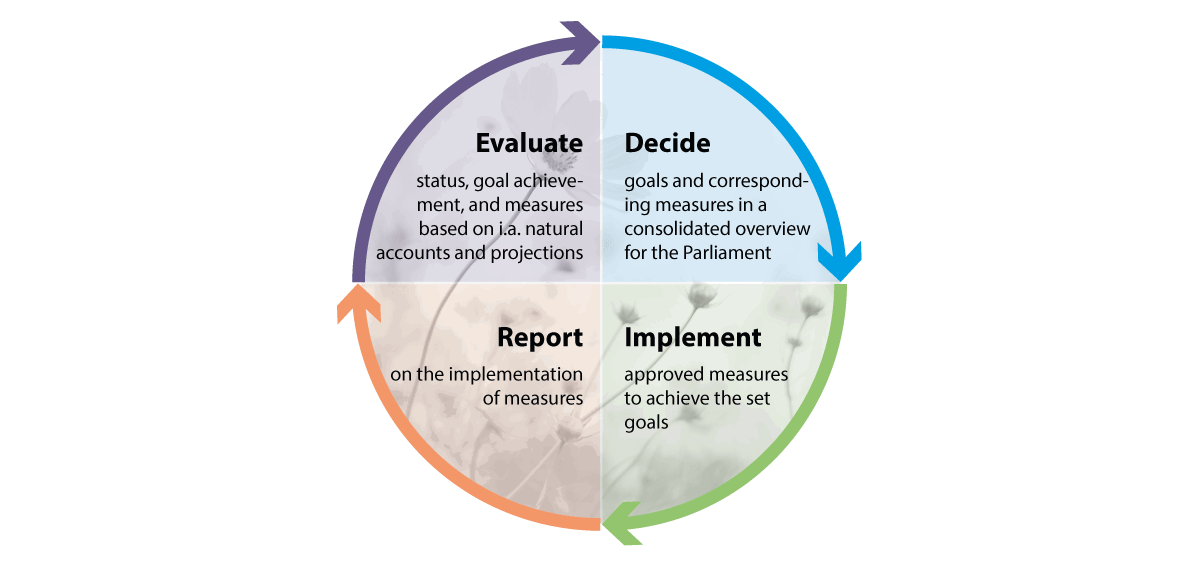

Overall, this ensures a systematic approach that allows for regular decision-making, implementation, reporting and evaluation of the actions to achieve the targets, see Figure 5.1. This provides an excellent basis for Norway’s contributions to and reporting on the national follow-up on the KMGBF, particularly target 14, see Chapter 6.14.

Figure 5.1 Regular Reviews of status, actions and target attainment for biodiversity

Integrated management comprising regular decision-making, implementation, reporting and evaluation of actions. The elements will, to some extent, take place in parallel with a repetitive and continuous process.

Source: The Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment

5.2 Nature accounting

In the Hurdal Platform, the Government reported that it would develop good methods for how to carry out nature accounting and has initiated the work to develop national nature accounts in line with the UN system for nature accounts, see box 5.1. The nature accounts will provide systematic and regularly updated knowledge of the dispersion and state of different ecosystems and ecosystem services. This will provide a more comprehensive overview than what is available today, and an improved understanding of what biodiversity means for society and the economy. Nature accounting will allow us to follow biodiversity trends over time and regularly assess target attainment. This will provide national, regional and local authorities with a better platform for decision-making and selection of instruments associated with biodiversity management, land use and nature interventions. The goal is to establish tools that can help politicians to make appropriate local trade-offs so that local communities can develop while safeguarding biodiversity.

Textbox 5.1 International requirements and guidelines for Ecosystem accounting

In 2021, the UN adopted an international statistical framework of standards and principles for the preparation of ecosystem accounting for different administration levels.1 The UN framework (SEEA EA) contains standards for biophysical accounting in relation to the dispersion of ecosystems, the integrity of ecosystems and the supply and use of ecosystem services. Furthermore, the framework also includes principles for monetary accounts showing the monetary value of the supply and use of selected ecosystem services and the ecosystem capital of a country. Monetary accounts will make it possible to compare the value that the ecosystems contribute to the economic assets in national accounts.

Based on the work undertaken by the UN, the European statistical agency, Eurostat, is working to expand the EU Regulation on European Environmental Economic Accounts. The expansion will commit all EU member states to reporting Nature accounting in accordance with certain criteria. The EU Commission presented its proposal in 2022. The proposal was adopted by the European Council and European Parliament in early 2024 and is expected to be implemented by the end of 2024. Statistics Norway and the Norwegian Environment Agency are expecting Norway to be required to report in accordance with the expanded regulation from and including 2026.

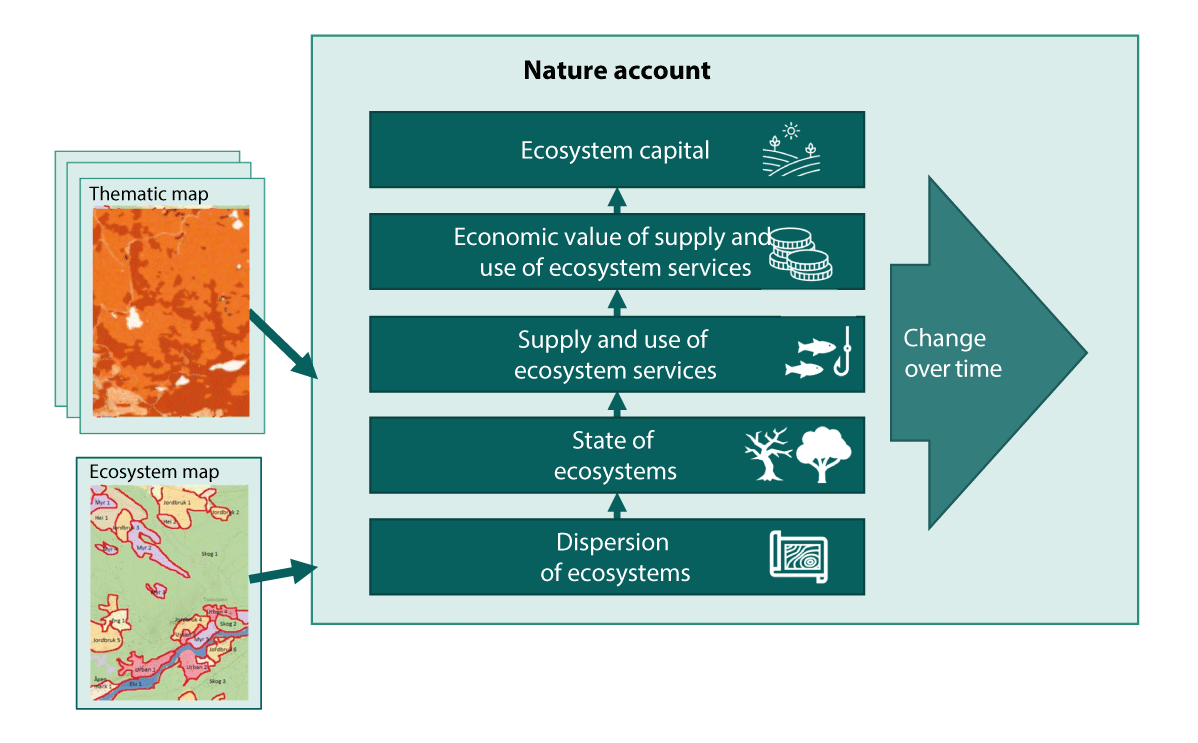

Figure 5.2 The elements of the UN nature account

The UN System of Environmental-Economic Accounting—Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA EA) is based on ecosystem maps. Based on the map data, three biophysical accounts (dispersion of ecosystems, state of ecosystems and supply and use of ecosystem services) and two economic accounts (economic value of supply and use of ecosystem services and ecosystem capital) and the associated trends can be monitored over time.

Source: The Norwegian Environment Agency

1 For further information about the framework, please see: https://seea.un.org/ecosystem-accounting.

Nature accounts are based on localised data and can be linked to specific accounting areas on maps and changes within defined areas. Accounts can be developed at different geographical levels: national, regional, local or for a specific natural area or development project. The Government is working to establish national nature accounts, as well as contributing data and guidance for nature accounts at regional, local and project level. The Government has announced a significant initiative on nature data for nature accounts going forward. In white paper no. 18 (2023–2024) Improved conditions for wild reindeer, the Government announced that it would create thematic nature accounts for wild reindeer to strengthen knowledge of the habitats of wild reindeer and changes to land use and ecosystem services. The Government has initiated work on a pilot for marine nature accounts for the Lofoten coastal zone. Marine nature accounts are also included as a key element of ocean accounts. Ocean accounts are addressed in further detail in Chapter 4.5 of white paper no. 21 (2023–2024) Norway’s Integrated Ocean Management Plans.

In 2023, the Norwegian Environment Agency summarised existing and easily accessible knowledge on natural land, integrity and ecosystem services into first-generation nature accounts.5 The summary showed that Norway has some data on land, integrity and ecosystem services at national and regional level. At the same time, however, some further work will be required for Norway to establish nature accounts compliant with international standards and commitments. The Norwegian Environment Agency and Statistics Norway are collaborating with relevant expert communities to ensure that accounts on the dispersion of ecosystems, integrity accounts and biophysical accounts on ecosystem services are ready by 2026.

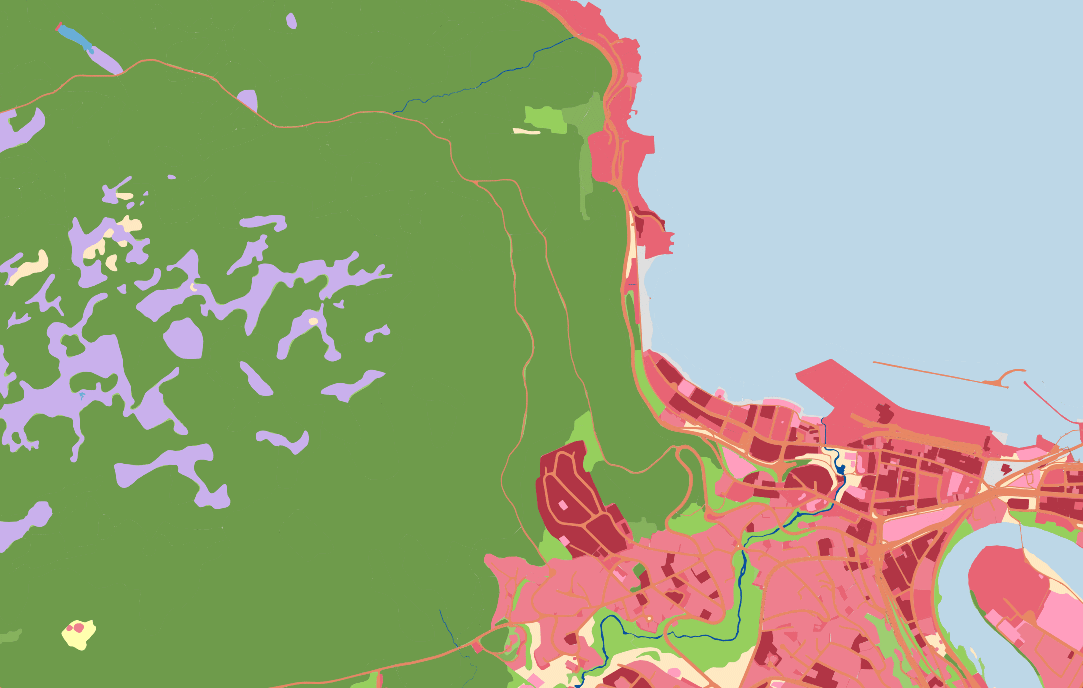

Figure 5.3 Excerpt of map from the test version of the base map for use in land accounts.

The figure shows ecosystems and land use divided by levels 1 and 2 of the EU typology. The excerpt is from the Municipality of Trondheim and shows, among other things, Bymarka with forests (green) and bogs (purple) and part of Trondheim city centre (reds).

Source: Geonorge.no

Accounts on the dispersion of ecosystems

Knowledge of the dispersion and distribution of different ecosystems is fundamental to comprehensive and ecosystem-based biodiversity management. Accounts on the dispersion of ecosystems are a fundamental element of nature accounts and will show land use changes between ecosystems and land use changes from natural land to other purposes. Maps showing how different biodiversity types are distributed in an area constitute important building blocks in the UN system for nature accounts. In collaboration with NIBIO and the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, the Norwegian Environment Agency published an initial version of a major ecosystem map based on existing data and the EU typology for the breakdown and demarcation of ecosystems in 2023.6 The map is comprehensive and there are no overlapping classes or gaps in the map. Based on the same typology as the major ecosystem map and dataset from the public map data, NIBIO, Statistics Norway, the Norwegian Mapping Agency and the Norwegian Environment Agency have drawn up a detailed base map for use in land accounts and nature accounts. The map constitutes a compilation of the most detailed data on land resources and land use available for Norway. An initial version was published in March 2024 and is now being tested, see Figure 5.3.7 Shortcomings in the existing map data mean that the map is not of equal quality for all ecosystem classes. Systematic work is under way to obtain new and more detailed data and new technology is being tested to achieve effective, unified and updatable data collection for the purpose of map supplementation. Further work on the base map for use in land accounting and nature accounts is addressed in Chapter 6.1.3.

Accounts on the integrity of ecosystems

In addition to knowledge on the dispersion and distribution of different ecosystems, it is also important to ensure knowledge of changes to ecosystem integrity. The Norwegian Environment Agency is working to develop integrity accounts that can be used in national nature accounts.

Accounts on access to and use of ecosystem services

The integrity of ecosystems and how land is used affect nature’s supply of goods and services of importance to people’s welfare – what are known as ecosystem services8. Biophysical accounts on ecosystem services provide an overview of the supply of different ecosystem services from different ecosystems and how these are used by stakeholders in the economy. The Norwegian Environment Agency and Statistics Norway are working to establish accounts on selected ecosystem services and have mapped models and datasets that can be used. Such accounts will cover e.g. the supply of crops and timber, pollination, climate adjustments and nature-based tourism.

Accounts on ecosystem services measured by monetary value

The UN framework assumes that the biophysical accounts on the dispersion of ecosystems, integrity and ecosystem services will form the basis for monetary accounts for selected ecosystem services and for ecosystem capital. Such accounts, measured by monetary value, will make it possible to demonstrate what ecosystem services contribute to national accounts and the importance of nature and ecosystem capital as part of Norway’s national assets. Nevertheless, establishing such accounts will take time and require resources and different methods and solutions will be tested for Norwegian conditions.

Textbox 5.2 Project-based nature accounts

Some enterprises have adopted targets to become land-neutral or nature-positive. Stricter sustainability reporting requirements and an increased focus on sustainable finance require enterprises to be familiar with and document how their activities depend and impact on nature. This gives rise to an increased need to measure and document how much a development project impacts on nature and to examine and select measures to reduce such impacts. This will be in line with the ASI principle (avoid, shift and improve) and the principles set out in the mitigation hierarchy. An increasing number of industries and enterprises are now looking at how project-based nature accounts can contribute to improved governance and documentation.

Project-based nature accounts should follow the entire lifecycle of a development project, from concept selection and early planning to completion of the construction. The level of detail of the accounts should be adapted for the decision to be made. In order to create project accounts, the integrity must be recorded and quantified prior to the implementation of the project and after all actions to reduce impact have been implemented. Internationally, there are methods in place to measure the impact on nature at project level and work is being undertaken in several areas to develop the methodology and adapt it to Norwegian conditions. The Norwegian Environment Agency is developing guidance for both project-specific and local and regional nature accounts. Such guidance will contribute to more consistent use of methodologies and concepts and will help enterprises wishing to establish nature accounts for their projects. The guidance will supplement existing guidance for e.g. impact assessments and must be viewed in the context of climate and energy accounts for major development projects.

5.3 Menu of Measures for ecosystems

The Government plans to establish menus of different measures that will help maintain a diversity of ecosystems with good ecological status. First to have been published is a Menu of Measures for the forest ecosystem, which is presented in Chapter 5.3.1. The Government will use the experiences from the work on the Menu of Measures for forests to establish similar menus of measures for the major ecosystems of mountains, and of cultural landscapes and open lowlands. Integrated management has already been established for the ecosystems of oceans, coastal regions, water and wetlands through the integrated ocean management plans and water management plans in accordance with the EU Water Directive and the Nature Strategy for Wetlands.

Sectoral responsibility is fixed and the responsibility to implement the adopted actions will fall to the different sectors. In addition to the implementation of suitable actions, the Norwegian Environment Agency will also be responsible for comprehensive coordination and policy harmonization. This includes coordinating reporting on implemented measures. In consultation with affected authorities, the Norwegian Environment Agency will be tasked with obtaining the scientific and technical basis required for updated menus, including proposals for any new measures.

5.3.1 Menu of Measures for forests

The Government’s Menu of Measures for the forests major ecosystem is presented below. As part of the work on a Menu of Measures for forests, the Norwegian Environment Agency and the Norwegian Agriculture Agency have been commissioned by the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment and the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food to draw up a joint knowledge platform on the ecological status of Norwegian forests.9 In consultation with other affected agencies, they have also assessed relevant measures with associated instruments that could help maintain or improve the status of forests. This work formed the basis for the Government’s Menu of Measures for forests.

Ecological condition in forests and anticipated developments

Chapter 3.2.4 provides an overall overview of the condition and impacts in the forest ecosystem.

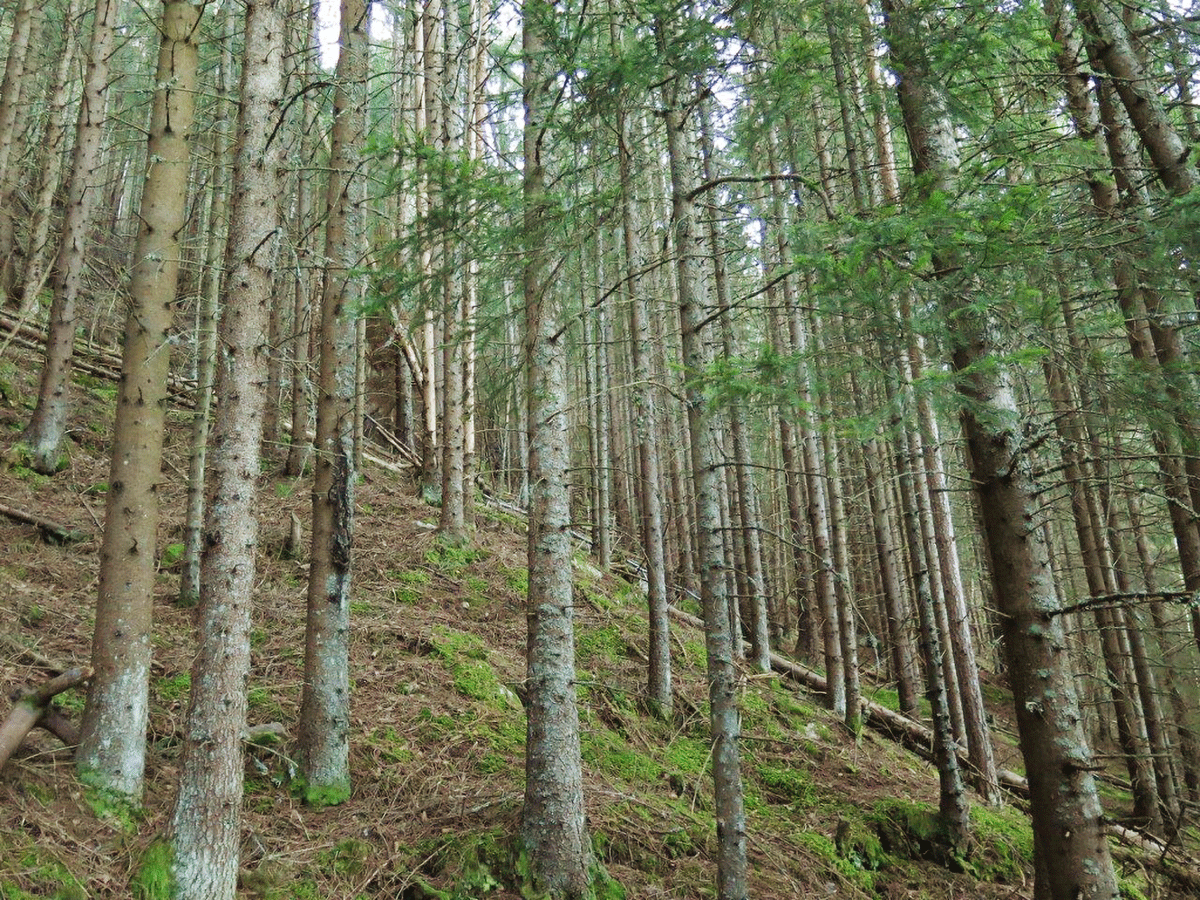

Figure 5.4 Planted spruce forests

Planted spruce forests on Skreikampen in the Municipality of Eidsvoll, Akershus. The trees are often of the same height in such planted cultural forests.

Photo: Tom H. Hofton

The assessment system for ecological condition provides a simplified representation of ecological status condition at national and regional level based on indicators that are weighted equally. The system does not differentiate between different types of land and is not designed with practical forest management in mind. The assessment system therefore has limited value for the practical management of forests.

In order to be able to assess relevant measures to maintain or improve ecological status, the Norwegian Environment Agency and Norwegian Agriculture Agency have developed a knowledge platform for 13 selected indicators that can be affected by forestry measures, restoration measures or the absence of measures, with a focus on productive forests as part of the scientific and technical basis for the Menu of Measures for forests. Table 5.1 provides a summary of the trends for the indicators.

Table 5.1 Indicators for ecological condition in productive forest, with trends in the indicators during the 1997–2021 period and the direction that will indicate improved ecological condition going forward

|

Indicator |

Trend in indicator from 1997–2021 |

Trend indicating improved ecological status going forward |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Deciduous tree admixture in coniferous forests |

Economically viable land |

Increase (+34%) |

Increased deciduous admixture in coniferous forests |

|

Protected areas |

Increase (+27%) |

||

|

Strains of valuable deciduous trees |

Economically viable land |

Increase (+17%) |

More strains of valuable deciduous trees |

|

Protected areas |

Increase (+29%) |

||

|

Rowan-Aspen- Sallow |

Economically viable land |

Increase (+48%) |

Increased volume of RAS species |

|

Protected areas |

Increase (+110%) |

||

|

Biologically old forests |

Economically viable land |

Increase (+120%) |

Increased land with biologically old forests |

|

Protected areas |

Increase (+205%) |

||

|

Dead wood |

Economically viable land |

m3 increase (+64%) |

Increased volume of dead wood in all dimensions and degrees of decomposition |

|

m3/hectare increase (+7%) |

|||

|

Protected areas |

m3 increase (+77%) |

||

|

m3/hectare increase (+22%) |

|||

|

Large trees |

Economically viable land |

Increase (+34%) |

Increased number of trees with large dimensions (>30 cm) |

|

Protected areas |

Increase (+39%) |

||

|

Crown classes |

Economically viable land |

Increase (+79%) |

Increased land with multi-layered forests |

|

Protected areas |

Increase (+121%) |

||

|

Blueberry coverage and crown density |

Economically viable land |

Stable |

Increased blueberry coverage |

|

Protected areas |

Stable |

||

|

Riparian zones |

No land differentiation |

Stable |

Increased land volume to which comprehensive consideration has been given |

|

Introduced coniferous trees |

Increased occurrence (negative trend) |

Reduced area and occurrence of introduced coniferous trees |

|

|

Red elder and other high-risk alien species |

Unavailable |

Reduced occurrence of red elder and other alien species with very high ecological risk |

|

|

Wildfires – scorched land |

Unavailable |

Improved access to scorched land |

|

|

Endangered species and biotopes |

Endangered species (stable) |

Extinction prevented and improved trends for endangered species and biotopes |

|

|

Endangered biotopes (negative trend) |

|||

In summary, 7 of the 13 indicators have experienced a positive trend, 3 indicators are stable, 2 indicators have experienced a negative trend, and it is not possible to specify a trend for two of the indicators. All regions have experienced a positive trend in key indicators such as dead wood, rowan-aspen-sallow and biologically old forests and it is reason to expect continued positive trends for these, in part due to the stricter environmental requirements for forestry management and certification schemes that have been implemented in recent decades. At the same time, an increasing volume of forests are being impacted by stand-based forestry, while there are fewer volumes of forests left without any signs of recent interventions. This is particularly true for coniferous forests in Eastern Norway.

Although the proportion of endangered species in forests has been relatively stable over recent decades (cf. the Norwegian Biodiversity Information Centre Red Lists for Species since 2006), the 2021 Norwegian Red List for Species shows that 86 per cent of endangered species in forests are declining. This means that a high number of species have experienced a population decline since the previous red list (2015) without this necessarily resulting in changes to the red list classification. Therefore, only looking at changes between the number of species in the red list categories does not provide a complete overview of the situation. If population declines continue, it could lead to more species being moved to a more critical category of endangerment.

The Storting has adopted a national goal of protecting 10 per cent of Norwegian forest areas. Currently, 5.3 per cent of forests are protected. The protected forest areas currently have a relatively high ecological condition. Most protected forest areas will maintain or improve the condition through natural development.

NIBIO’s projections show that increasing levels of development for transport, energy and settlement will lead to continued loss and fragmentation of forests.10 By 2050, deforestation of 1,800 km2 and afforestation of about 1,600 km2 are expected. Afforestation is predominantly caused by the treeline moving up towards the mountains as a result of a warmer climate and forests that become established here will often not have the same biodiversity value, capacity for carbon capture or forestry significance, such as forests lost to development projects which are consistently situated in lowlands.

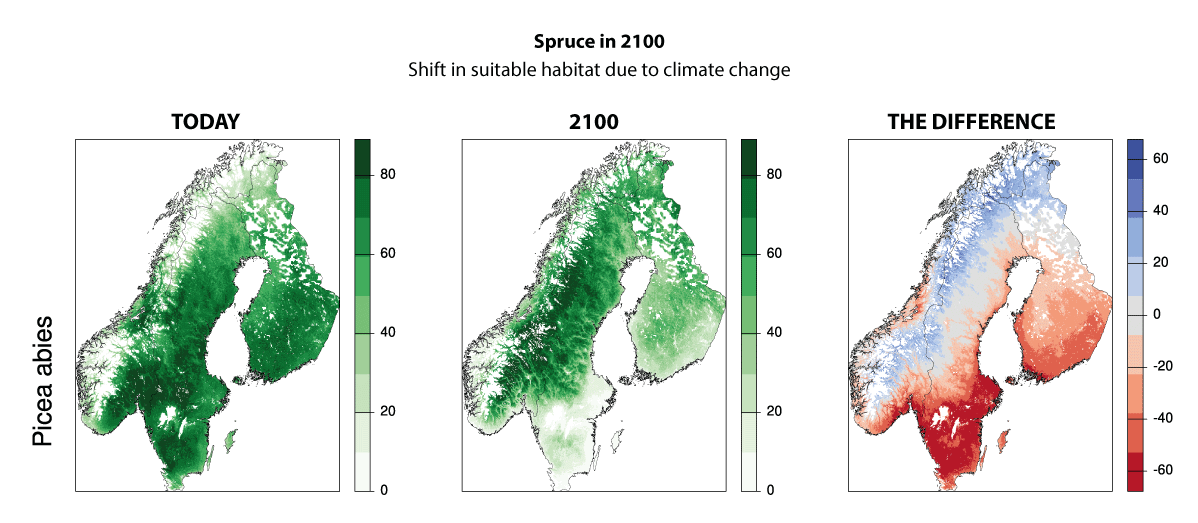

Figure 5.5 Anticipated trend in viable habitats for spruce by the year 2100

Habitat quality today and in 2100 (in an average scenario for climate change, SSP245) and the differences between the two points in time for Norway spruce (Picea abies) in Scandinavia. The numbers indicate the probable occurrence of spruce, given that the areas can be colonised naturally or through assisted migration. The red colour on the map on the right indicates that the land is less suitable for spruce.

Source: Panzacchi et al. (2024)

A synthesis report on the impact of climate change on the ecological condition of forests by the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment shows that climate changes will result in moderate ecological changes to Norwegian ecosystems in the short term (by 2050) and more extensive and negative changes in the longer term (by 2100). Increased average temperatures and precipitation may have certain positive effects, but extreme weather and climate-related disturbances may have major, increasingly negative effects on the forest ecosystem. Furthermore, climate change will lead to an increased probability of fungal diseases, pests, introduction of alien species, more frequent incidence of windthrow and cascading impacts in forests. Climate change will also likely lead to significant changes to the living conditions of species by 2100. Trees live for many years and changes to living conditions resulting from climate change mean that the living conditions for trees that are growing up today will deteriorate in many places, while conditions will improve for other, more southern species. See also Figure 5.5.

Goals for forests

We have relatively good state of knowledge of the condition of forest ecosystems through long time-series of mapping and monitoring of Norwegian forests, as well as various reports, studies and scientific publications. The Government has set various targets for forests that maintains a balance between the protection and sustainable use of Norwegian forests.

In forests that are protected under the Nature Diversity Act, the purpose is to conserve specific natural assets, and the ecological status should therefore be as good as possible. For most protected areas, there will be a desire for the area to develop freely and the aim will therefore be to approach close to natural condition by 2050 for both individual indicators and the ecosystem as a whole. As part of the work to achieve the targets, it will also be relevant to eliminate negative impacts that influence key natural assets and ecological condition for both existing and future protected areas.

For the remainder of Norwegian forests, the Government is seeking to facilitate improved ecological condition by 2050. These forests are diverse, with great variation in biodiversity and ecological condition. Here you can find anything from scattered mountain forests to highly productive and valuable deciduous forests and everything from felled areas to ancient forests with limited signs of forestry. There will be great variation in how such unprotected forests will be used going forward. In productive forests that are economically viable for timber production, there must be active and sustainable forestry that safeguards the competitiveness of the forestry industry. At the same time, important natural assets such as endangered species and habitats must be conserved, including through key biotopes and new protected forest areas. In forests that are not economically viable for timber production, the main pressures come from development and land-use change and an integrated and sustainable land management approach is necessary to make sound trade-offs between competing interests. It is therefore the sum of measures and instruments in forestry management, environmental management and land management that will ensure an improving trend in the ecological status of forests that are not protected. In order to assess the further development of ecological status, the Government will follow the further development of 13 selected indicators highlighted by the Norwegian Environment Agency and the Norwegian Agriculture Agency in its scientific and technical basis for the Menu of Measures for forests (see Table 5.1).

The Government has established the following goals for forests in Norway:

-

Forests protected under the Nature Diversity Act will have an ecological status close to natural condition by 2050.

-

In other forests, ecological status as measured using the agencies’ indicators will be improved by 2050, while active and sustainable forestry is maintained on on economically viable land, and the competitiveness of the forestry industry is safeguarded.

The targets for ecological condition in forests must also be viewed in the context of the Government’s objective of reduced developments on natural land, see Chapter 5.4.1.

Measures for forests

The Government’s Menu of Measures for forests is presented below. The Government believes that these are the measures that will yield the best results when implemented through enhanced knowledge and expertise – both in relation to where the important natural assets are and how they should be managed when concurrent forestry activities might be carried out in the same area.

The Norwegian Environment Agency and the Norwegian Agriculture Agency have presented a total of 16 measures in their scientific and technical basis to maintain or improve the ecological condition of forests, see box 5.3. The agencies note that the implementation of measures and instruments requires integrated assessments of advantages and disadvantages to be carried out in relation to relevant societal interests and knowledge hubs should be adequately involved. The need for measures and instruments must be considered in relation to the trend of the indicators of forest condition.

A thorough review has been carried out by the two agencies and the ministries that tasked the agencies with the assignment.

The Government will

-

implement the following Menu of Measures for forests with the aim of improving the ecological condition of forests by 2050

Textbox 5.3 The Norwegian Environment Agency and the Norwegian Agriculture Agency’s scientific and technical basis for a Menu of Measures for forests

In its report Knowledge Platform on the Ecological Condition of Norwegian Forests and an Examination of Measures, the Norwegian Environment Agency and the Norwegian Agriculture Agency present measures and associated instruments for forestry management, environmental management and land management in various sectors. The agencies have not examined whether there is a need for measures or the dimensioning of measures and provide no recommendations.

The 16 measures examined by the agencies are:

-

Increasing the proportion of continuous forestry methods

-

Increasing the retention of dead trees during felling

-

Increasing the retention of large, coarse deciduous trees during felling

-

Making the right choice of tree species after felling

-

Young forests stand tending in order to improve ecological condition

-

Extending rotation periods

-

Reducing loss in plant fields through the combating of alien species

-

Restructuring forests through small-scale clear cutting in thinning stands

-

Increasing the preservation of ecological function in riparian zones during felling

-

Preserving scorched areas following wildfires

-

Accelerating the implementation of targeted protected forest areas

-

Improving ecological condition in protected forest areas

-

Increasing the restoration of forests

-

Improving the safeguarding of endangered biodiversity

-

Increasing the fight against invasive alien species

-

Reducing the reallocation of forests for other purposes

Source: The Norwegian Environment Agency and the Norwegian Agriculture Agency (2023).

Improving the safeguarding of endangered biodiversity in forests

The Government will pursue an integrated policy to balance the conservation of nature against other societal interests, thereby contributing to improving the trend for endangered and near-threatened species and habitats. Through integrated and coordinated land management, all affected sectors will contribute to the sustainable management of forests and to achieving the targets established for forests by the Government. Area-based instruments are addressed in targets 1, 2 and 3 in Chapter 6.

As discussed in further detail under target 4 in Chapter 6, a follow-up plan was established in 2021 for 23 species and 12 habitats, of which 13 species live entirely or partially in forests and 3 habitats are forest habitats. The measures are broad and include both legal and economic instruments. Protected areas and habitat management in existing protected areas, as well as the key biotopes in forestry, are particularly important ongoing measures for safeguarding endangered species in forests, cf. below. In their scientific and technical basis, the Norwegian Environment Agency and the Norwegian Agriculture Agency highlight three relevant measures to better safeguard endangered nature. These are an increased number of prioritised species and selected habitats under the provisions of the Nature Diversity Act, increased biotope mapping in forests and economic initiatives for endangered nature.

Increase expertise on continuous forestry methods

The Government wishes to safeguard important natural assets in forests by stimulating increased expertise on continuous forestry methods, including increased expertise on small-scale clear cutting in thinning stands in order to encourage both natural regeneration and greater variation. Through the Norwegian PEFC Forestry Standard, greater emphasis is placed on continuous forestry methods than previously. These are felling methods that are not suitable for all forests as the forest stability after felling and the land’s capacity for natural regeneration are key conditions. Continuous forestry methods may also yield lower production levels in the short term compared to clear felling, while continuous forestry methods may also have other negative impacts on forestry and biodiversity. Continuous forestry methods therefore require increased expertise on the part of forest owners and contractors alike and it is therefore necessary to consider skills development measures.

Obtain improved knowledge of the extent of forests affected by fire

Even though wildfires have a negative impact on a number of forest species, many species are also completely reliant on wildfires to complete a full lifecycle. In Norway, approximately 40 red-listed species are linked to wildfires and many fire-specific species appear following wildfires, even in small areas. The Government believes that there is a need for more knowledge about the overall current extent of forest affected by fire and whether this land area is sufficient to maintain the population of such specialised species over time.

Implement protection of forest areas in line with the Government’s adopted budget frameworks and further develop knowledge of the status of and trends in ecological condition in protected forest areas

In the follow-up plan for endangered nature, protected areas have been highlighted as one of the most important instruments in safeguarding endangered nature in Norway. Forests are protected, among other things, through a partnership between the forest owner organisations and the environment authorities on the voluntary protection of privately owned forests. Since the partnership launched in 2003, 924 protected forest areas have been established. There is great interest in the voluntary protection of privately owned forests and work is under way on a number of new protected forest areas. The Government also wishes to further develop knowledge of the status of and trends in ecological status in protected forest areas.

Follow-up and assess the measures in the report Old-growth Forest and Key Biotopes and report annually on development of land included in key biotopes

Key biotopes are areas with particularly important biotopes that are situated in productive forests and excluded from felling. The report Old-growths Forest and Key Biotopes11 drawn up by a working group comprising representatives from the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment and the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food lists several measures to improve the safeguarding of key biotopes and increase knowledge of the oldest forests. The recommendations are followed up by the Norwegian Agriculture Agency, the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food, NIBIO and the forest industry organisations. Measures include annual reporting on the extent of key biotopes and work on the knowledge platform that forms the basis for the Government’s instructions, as well as the proliferation, establishment and occurrence of organisms, etc. From 2021 to 2023, the land area containing key biotopes outside protected areas increased from 1037 to 1080 km2, now corresponding to approximately 0.9 per cent of the forest area.

Examine the need for any new measures and instruments for forests with a stand age exceeding 160 years

84 per cent of the 1330 endangered species in forests are associated with old forests. Adequate management of old-growth forests is therefore crucial in safeguarding endangered biodiversity in forests. The Government will further examine the need for new measures and instruments to safeguard natural assets in the old-growth forests.

Follow up on Storting request no. 519 (Document 8:40 S (2022–2023))

Environmental registration in forests is a form of mapping performed as part of ordinary forestry planning for the purpose of obtaining information about important natural assets in forests. On this basis and in accordance with the forest certification schemes, forest owners can select biotopes to conserve through e.g. key biotopes or other biologically important areas.

In connection with the Storting request Document 8:40 S (2022–2023) on a new forestry policy, the Storting decided the following on 14 March 2023, cf. resolution no. 519:

The Storting asks the Government to review the current method for collection, registration and monitoring of important natural assets in Norwegian forests, to consider measures to ensure that the intention of environmental registration is met and that such environmental records are of adequate quality.

This could lead to an improved knowledge platform for sustainable forestry. Together with the National Forest Inventory of Norway at NIBIO, the Norwegian Agriculture Agency has developed a monitoring scheme that is being implemented during the 2024 and 2025 field seasons. NIBIO will also review the follow-up on the monitoring instructions, etc. for the purpose of evaluating both the instructions and follow-up thereof after more than 20 years of environmental registration. The Ministry of Agriculture and Food will come back with plans for further follow-up once these two assignments have been completed.

Continuation of the grant scheme for forestry planning with environmental registrations in forests

The land area with new biotope data increases by 50,000–70,000 decares every year and provides the basis for local environmental considerations for each plot, in part through the selection and management of key biotopes and the management of other biologically important areas such as riparian zones, but also assessments of felling methods for each forest stand. The grant scheme for forestry planning with environmental registration in forests is an important premise for succeeding in this.

Ensure systematic monitoring of the indicators highlighted by the agencies for ecological condition in economically viable forests

As mentioned at the start of this chapter, the Norwegian Environment Agency and the Norwegian Agriculture Agency have created a scientific basis for the 13 selected indicators that form the basis for this Menu of Measures for forests. The Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food and the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and Environment will adapt any further knowledge collection in order to monitor trends in these indicators.

Further consider other measures from the agencies’ investigation

Based on new, updated knowledge, the Government will be able to further consider the other measures from the agencies’ investigation, cf. box 5.3, that could contribute to meeting the Government’s targets for forests and fewer development projects on natural land.

One ongoing challenge is to ensure that there is an appropriate joint decision-making basis for measures associated with the use and conservation of forests. Going forward, the ministries will prioritise such joint knowledge efforts.

5.4 Integrated and sustainable land-use management

The use of land provides, among other things, growth and development through settlement, transport and industrial activities. At the same time, land use changes constitute the greatest threat to biodiversity on land in Norway, are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions and result in the loss of ecosystem services. Some land use changes are irreversible and impossible to restore, while other land use changes result in a deterioration in biodiversity that can be difficult or time-consuming to restore. Development projects contributing to loss of land «bit-by-bit» can make it difficult to maintain an overview of the overall impact on biodiversity. The use of land can also have an impact on larger areas as the biotopes of species become fragmented and reduced. In turn, this weakens the resilience of ecosystems.

At the same time, only around 1.7 per cent of the overall land mass in Norway is developed and approximately 3.5 per cent is used for agricultural purposes. The majority of Norwegian nature is not affected by development projects.

Integrated and sustainable land-use management is essential in achieving various societal targets and achieving an appropriate balance between different interests. Spatial planning and reallocation of land-use within one nautical mile of the sea boundary are largely managed by local authorities pursuant to the Norwegian Planning and Building Act. The state provides guidance and instructions for planning through legislation, regulations and government planning guidelines, see further details of the different stakeholders’ roles and regulations for land-use management under target 1 in Chapter 6.1.2.

Based on figures from Statistics Norway and NIBIO, the Norwegian Environment Agency estimates that future development projects that lead to loss of land in natural land will account for between 35 to 40 km2 annually.12 Natural land includes all land other than developed land and agricultural land. The estimate means that 210 to 240 km2 of natural land will be developed by 2030 and 910 to 1040 km2 by 2050. In comparison, 5631 km2 (1.7 per cent) of Norway’s land area and 11,222 km2 (3.5 per cent) of agricultural land are developed as of 2024.13 Figure 5.6 shows land use changes between 1990 and 2022. The development of nature accounts will strengthen knowledge of changes to ecosystem dispersion, see more in Chapter 5.2.

Development projects that lead to loss of natural land also have a negative impact on adjacent land. This means that much larger areas of natural land are degraded in addition to the directly developed land. According to the Norwegian Environment Agency, the extent of untouched nature in Norway14is constantly decreasing. Figures from 2023 show that 43 per cent of mainland Norway is considered untouched nature and 11.2 per cent is considered wilderness.15 From 1998–2023, the untouched natural land in Norway decreased by approximately 6.8 per cent (10,244 km2).

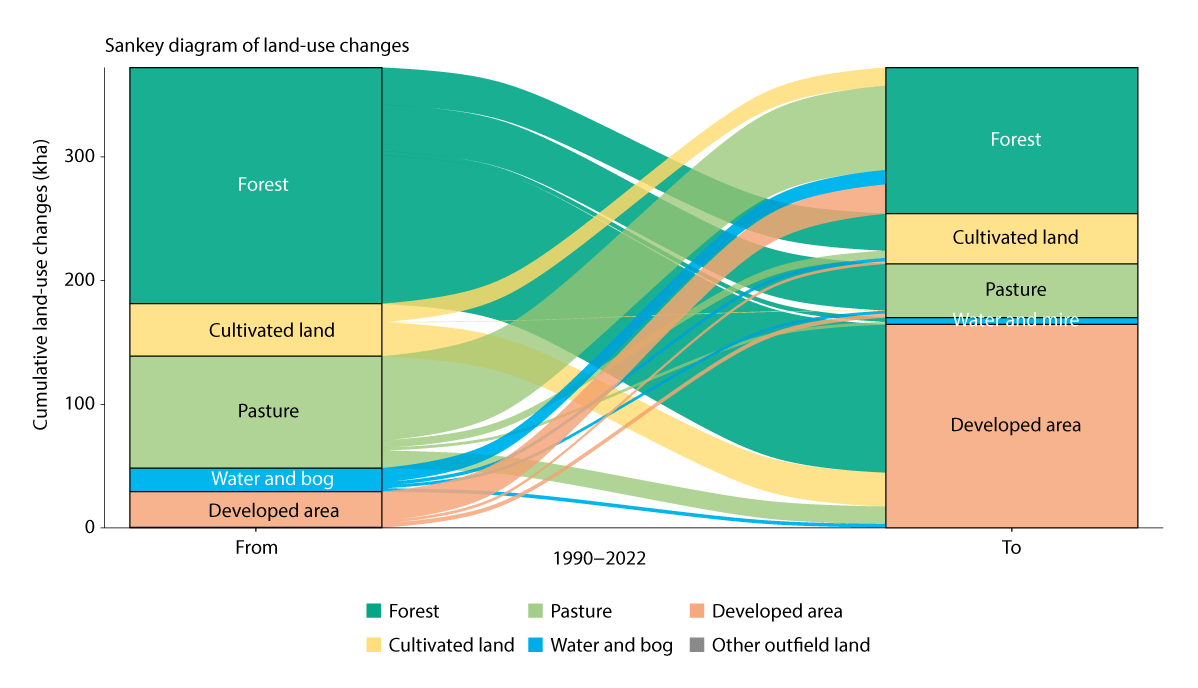

Figure 5.6 Changes to land use categories between 1990 and 2022

The figure shows land for which use has changed so significantly that the land classification has changed in the IPCC land use classification between 1990 and 2022 and what the land use has been changed to. The figure shows only land that has been reclassified, not all land.

Source: Norwegian Institute for Bioeconomy (NIBIO), based on figures from the Norwegian National Forest Inventory.

There are extensive plans for development projects on natural land in Norway in the coming years. The Norwegian Environment Agency has compiled data on land that has been allocated for development purposes under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act16 and other legislation17. Overall, this includes an area of about 4000 km2 (1.2 per cent), with about 90 per cent of this being natural land today. Land allocated to residential, holiday and commercial purposes amounts to 2166 km2. As of March 2024, development projects totalling 750 km2 have been planned, reported or applied for. Development projects for transport, sports and other purposes are estimated at approximately 1000 km2. The estimates are associated with uncertainty.

Natural land is a limited resource, even if we have a lot of it in Norway. There is no comprehensive overview of how, or to what extent, biodiversity and climate have been taken into account in land use plans and permits under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act. Together with land-use change happening bit-by-bit due to development projects, this makes it difficult to ensure integrated and sustainable management of biodiversity. The evaluation of the Norwegian Planning and Building Act (EVAPLAN) from 2018 indicates that the act does not adequately safeguard climate and biodiversity considerations in local planning.18 This is partly due to a lack of capacity and expertise in local authorities and partly due to the weighting of climate and environmental considerations relative to other interests. EVAPLAN also notes that the Norwegian Planning and Building Act does not provide a sufficient system to identify the overall impact of land use policies for greenhouse gas emissions, cultural environments and biodiversity. Furthermore, a report from the Auditor General from 2019 shows that there is a risk that national and significant regional interests not being adequately safeguarded in spatial planning. See further discussion on initiatives and instruments to safeguard biodiversity considerations in spatial planning in Chapter 6.1.3.

Norway has a good system in place to manage its land through the Norwegian Planning and Building Act and sectoral legislation, see further details under target 1 in Chapter 6, but there is high pressure on land in many areas. If biodiversity considerations are not assigned greater weighting in decisions on land use changes, there could be a risk of loss of important biodiversity and major greenhouse gas emissions could also arise due to land use changes going forward.

5.4.1 Targets to reduce the number of development projects that contribute to loss of areas of especially high ecological integrity

A target to reduce development projects that lead to loss of cultivated soil in Norway has been established. The target for protection of cultivated soil states that a maximum of 2000 decares will be reallocated each year and that the target must be met by 2030. This has contributed to a decrease in the reallocation of cultivated soil. In the National Expectations for Local and Regional Planning 2023–2027, the Government urges local authorities to establish targets to decrease loss of land areas. Nevertheless, there has not previously been any such national targets. In order to set the direction for the joint effort it will take to reduce the loss of natural land in Norway, the Government will establish the following as Norway’s national target to global target 1 of the KMGBF:

By 2030, initiate actions to reduce the number of development projects that contribute to loss of areas of especially high ecological integrity, and by 2050, limit the net loss of such areas to a minimum. The implementation of the target will ensure an approach that secures participatory, integrated and biodiversity inclusive spatial planning, respecting local governance and the rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Especially important natural land includes biodiversity of national and significant regional interest, cf. The Ministry of Climate and Environment’s Circular T-2/16 National and significant regional interests within the environmental domain – clarification of the environmental authorities’ objection practices.19 This includes protected areas, selected habitats and priority species, endangered habitat types, endangered species and their biotopes, important functional areas for wild reindeer, etc.

The national target will form the basis for central activities and the Government’s work going forward, such as the work on the National Transport Plan, National Expectations for Regional and Local Authority Planning, central government planning guidelines, etc. The aim is not to reduce the opportunity to develop socially beneficial renewable power production and power lines.

Local authorities play a key role in the work to preserve natural land through spatial planning and this role remains unchanged. This will be a directive target for local authorities. Furthermore, the Government will facilitate the important role of local authorities through tools and access to knowledge, see more under target 1 in Chapter 6.1.

5.4.2 Principles for sustainable land management

As mentioned, the state provides instructions and frameworks to contribute to integrated, effective and sustainable land management in local and regional authorities. Examples include the provisions set out down in the Norwegian Nature Diversity Act and central government planning guidelines under the Norwegian Planning and Building Act. Experiences from current land management are positive but also show that there is a need for more attention to the overall scope and impact on biodiversity. There is also a lack of principles that adequately show that the most useful initiatives for society are prioritised and that we do not use more land than necessary.

In order to achieve the national target to reduce the loss of natural land of especially high ecological integrity, the Government will highlight principles that will contribute to less land-intense and more sustainable land management going forward.

These principles do not constitute a new management system but national, policy guidelines that must be practiced within the framework of laws, regulations and governmental planning guidelines. They will form the basis for central, regional and local land management and contribute to predictability and data to meet key societal needs at national and local level. They will underpin local authorities’ work to make good decisions for biodiversity within local governance and take into account differentiated land management adapted to regional and local conditions. The principles therefore differentiate between rural and urban areas in order to ensure that rural municipalities have the necessary freedom to act to facilitate jobs and development. As discussed in Chapter 3.1, biodiversity varies between different parts of the country and from municipality to municipality. As an example, the extent of endangered nature, protected areas and topography and geology variations differs. This means that the local authorities have different conditions and starting points for the work to safeguard biodiversity. The principle of prioritised development purposes could be more relevant in rural areas than urban areas, as many developments for renewable power and defence are planned for open land. At the same time, the principles do not affect local government, and the principle provides predictability that local authorities can take into account in spatial planning.

The highlighted principles have been taken from the National Expectations for Regional and Local Planning, the Government planning guidelines, regulations on impact assessments, the Norwegian Planning and Building Act and the Norwegian Nature Diversity Act, except principle c).

-

a) Principle of good localisation and implementation of development projects:

When planning and implementing new development projects, it would be appropriate to choose a location and development solution that avoid negative impact on biodiversity and agricultural land, the impacts that cannot be avoided must subsequently be limited and direct impact must be repaired after development. Compensation is the last resort to mitigate the loss of biodiversity and agricultural land, including agricultural, natural, recreational and reindeer husbandry land. When adopting plans and initiatives, it is important to describe the alternatives that have been considered in order to limit damage to nature and agricultural land.

-

b) Principle of documenting impact:

In decisions on development projects that lead to loss of biodiversity, the impact should be described to the extent possible in order to show how much natural land will be lost and what has been done to limit damage to nature.

-

c) Principles on prioritised development purposes:

Local, regional and central authorities must collaborate to facilitate adequate land for renewable power production, power lines, defence purposes and critical digital infrastructure. In land management, purposes of especially high public utility such as renewable power production, power lines, critical digital infrastructure and defence will be assigned greater weighting in the event of conflicting development purposes.

-

d) Principles of spatial planning:

Development patterns and transport systems must be coordinated in order to achieve space-efficient solutions and reduce transport requirements. In planning, emphasis must be placed on the following:

-

Promoting sustainable, compact and attractive urban and suburban areas with adequate access to green structures and natural areas.

-

In smaller places and sparsely populated areas, the development of viable local communities is facilitated.

-

In rural areas, the land-use element of the municipal master plan may facilitate scattered residential development on land set aside for agricultural, natural and recreational areas. Densification and transformation of residential and commercial land must be considered and should be utilised before new development zones are set aside and used.

-

The overall development pattern should be clarified through regional or inter-municipal plans. Plans should draw long-term boundaries between urban and suburban areas and large, continuous agricultural, natural and recreational areas, as well as areas set aside for Reindeer husbandry.

-

Especially important areas for recreation and biodiversity must be taken into account, as well as carbon-rich areas, so that the quality and capacity for ecosystem services, carbon storage and climate adaptation is maintained in these areas.

-

Consideration must be given to valuable agricultural land, as well as ensuring large, continuous agricultural, natural, recreational and reindeer husbandry areas and connections between these, as well as to safeguarding Sami interests.

-

Considering whether previously adopted land use that is inconsistent with national land use policies or regional guidelines should be removed or reduced.

-

When carrying out planning that affects Sami reindeer husbandry areas, local and regional authorities must conduct consultations with affected Sami stakeholders.

-

-

e) Polluter Pays Principle:

The developer must cover the costs of preventing or limiting the damage caused by projects if this is not unreasonable based on the nature of the projects and damage.

-

f) Principle of differentiated land management:

Land management must distinguish between urban and rural areas in order to help develop strong and attractive local communities.

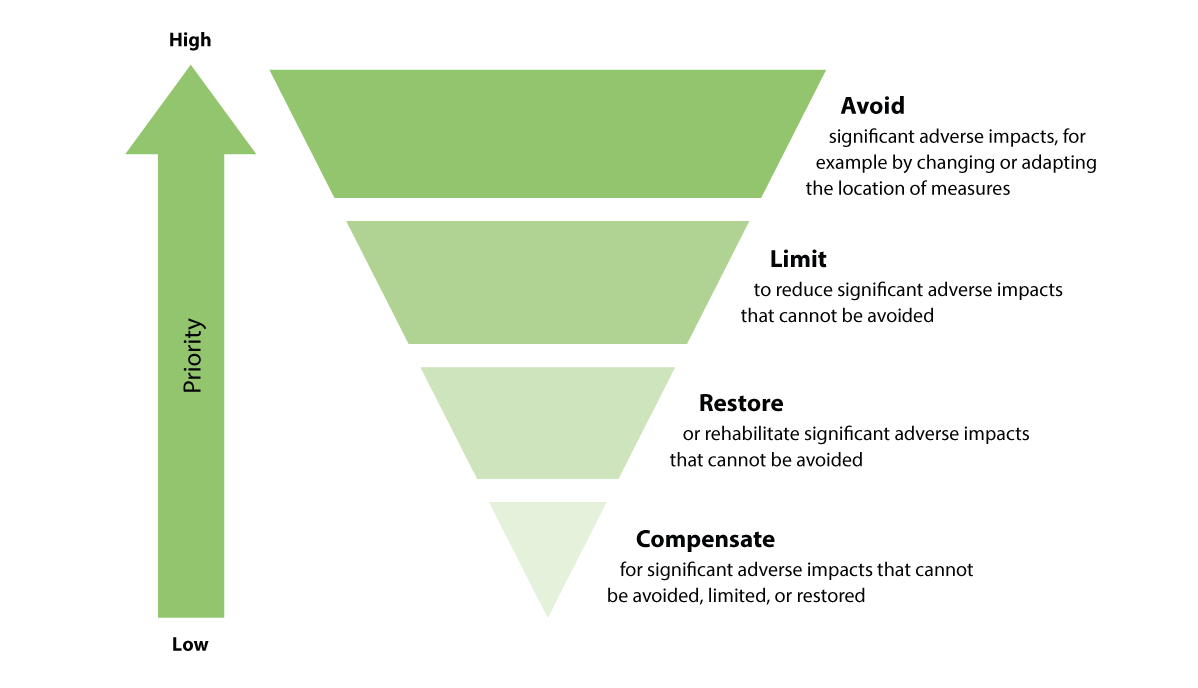

Textbox 5.4 Mitigation hierarchy

The mitigation hierarchy consists of four types of measures that will reduce the negative impact a physical development has on biodiversity. In order of priority, these are measures to 1. avoid, 2. limit, 3. repair and 4. compensate for adverse impact. The hierarchy has been used for a long time both nationally and internationally as a method of limiting damage to nature.

The most effective measures ensure that we can avoid damage to nature. This could include relocation of or changes to development projects to avoid interfering in natural land. There are also measures to limit adverse impact. These could include measures to adapt the location and design to local conditions. During and after the implementation of the development, measures must be taken to repair any nature damaged through the development. This is especially relevant to damage from construction work – embankments and other interventions in the terrain can, for example, have vegetation planted and be restored. If everything possible has been done to limit and repair damage and there is still a negative impact on nature, it is necessary to consider measures to compensate for such damage. Such compensation is considered the last resort to mitigate damage to nature.

The regulations on impact assessments set out rules on how the Mitigation hierarchy must be used in fact-finding and decision-making.

Figure 5.7 Mitigation hierarchy

The mitigation hierarchy shows that it is paramount to minimise any adverse impact on the environment and climate. When this is not possible, it is necessary to limit damage and repair land. Compensation is the last measure on the list.

Source: The Norwegian Environment Agency (2023d).

Source: The Norwegian Environment Agency (2023d). Guide M-1941.

5.5 Sustainable use of nature

Humans have always used nature. We will continue to do so. Sustainable use of biodiversity entails preserving biodiversity for future generations to enjoy the same benefits of biodiversity as we do today, see more in Chapter 2.2. This assumes that nature’s contributions to people, including ecosystem functions and services are maintained.

This subchapter describes the work in selected sectors to ensure sustainable use of nature.

5.5.1 The agricultural sector

The Storting has adopted the following national targets for agricultural policy:

-

Food security and preparedness

-

Nationwide agriculture

-

Increased value creation

-

Sustainable agriculture with lower greenhouse gas emissions

Agriculture

Agriculture encompasses a diverse range of farming systems based on the interaction between humans and nature and includes the cultivation, harvesting, restoration and management of resources. Through environmentally sustainable production, agriculture will contribute to common goods in the form of cultural landscapes and biodiversity, while also reducing pollution and greenhouse gas emissions and increasing carbon capture.

Agricultural cultural landscapes include a mosaic of fields, meadows and rough grazing and a combination of activities and elements in the landscape, as well as resources that have occurred over time and associated day-to-day use. Great variety in natural conditions and other conditions throughout the country has given rise to a diverse range of farming systems. The natural assets and rich species diversity of cultural landscapes have been developed as a result of long-term interactions between humans and nature and depend on the continuation of operations and landscapes. These assets are currently under bidirectional pressure through the discontinuation of previous farming systems and overgrowth on the one hand and intensification of farming on the other hand. Widespread use of less cultivated pastures in infields and outfields stands out as the farming system with the greatest potential to extend natural assets that have been accrued in earlier times. In our part of the world, such farming practices with outfield pasture are unique to Norway and a small number of other countries. The conservation of the diversity of cultivated plants and livestock is best achieved through continued use.20

Norway has limited topsoil and soil conservation is therefore a high priority. The current soil conservation target was adopted in 2023 and aims to decrease reallocation to less than 2000 decares each year and for the target to be achieved by 2030.

As we have particularly limited topsoil suitable for grains and other food crops, land in the most favourable areas is prioritised for food crops, while livestock farming primarily takes place in other areas that are less suitable for food crops. This distribution in production has served us well by developing self-sufficiency in food crops and agriculture throughout the entire country. At the same time, the distribution does entail some disadvantages in the form of e.g. high levels of manure and phosphorus in the most livestock-dense areas and more unilateral operation and use of mineral fertiliser in grain areas. In order for the distribution in production to be preserved, we also need to solve the associated challenges. This entails, among other things, reducing the runoff of nutrients, soil and pesticides from more cultivated production areas and achieving better distribution of phosphorus resources from manure and organic residual products. Report. to the Storting no. 11 (2023–2024) Strategy for increased self-sufficiency in agricultural goods and escalation plan for earning opportunities in agriculture shows that good agronomics, voluntary measures and requirements are important for maximising crop potential, improving quality in production and reducing climate and environmental impact.

The strategy emphasises increased plant production for food and feed as crucial in increasing self-sufficiency in food. It focuses on producing more vegetable foodstuffs in Norway, investing in the use of pasture resources and an increased Norwegian share in feed through both grass and grain feed.

Forestry

Norway has significant woodland resources, and a rich, varied biodiversity associated with forests. In Norway, we have exploited woodland resources from time immemorial. The industrial exploitation of forest resources in recent centuries has had an impact on the ancient forests we have today. Previously, it was common to fell the best and often the largest trees, so-called «diameter limit felling», with the result that large parts of the forests were scattered and overharvested a century ago. This is largely the origin of the ancient forests we have today and what are often referred to as «natural forests» with varying degrees of crown classes, ancient trees and dead wood. Today’s forests also include a significant degree of natural structures and compositions, but land without any trace of forestry accounts for very small areas. However, large parts of productive forests are made up of planted cultivated forests or forests that, to varying degrees, show traces of forestry and natural regeneration. That is why, depending on how long it has been since forest interventions and how significant such interventions were, there are gradual transitions between cultivated forests that have been actively managed and forests that are more dominated by natural processes with few or no traces of human activity. Of the 1330 endangered species in forests, 84 per cent are associated with ancient forests and proper management of ancient forests is therefore crucial to the preservation of biodiversity.

The Norwegian forestry industry is important. Active and profitable forestry and a competitive forestry industry are important to settlements, jobs and business development in large parts of the country. The potential for increased value creation is great, not least if parts of the large timber volumes that are exported can be refined in Norway.

Forestry provides the basis for trade and jobs throughout the country, while forests also provide some of the solution to climate challenges. Forests account for approximately one third of total greenhouse gas emissions in Norway. There is significantly greater growth than felling in Norwegian forests. This contributes to carbon-binding, but also shows the potential for creating new, greater assets based on forest resources.

The Norwegian National Forest Inventory shows that over the past century the volume of forests has increased from approximately 300 million cubic metres up to nearly one billion cubic metres, while forestry has taken out around one billion cubic metres.

The annual production from forests has been between 8 and 13 million cubic metres throughout this century, while growth has eventually developed from 10–12 million cubic metres one century ago to around 25 million cubic metres per year now.

Growth has increased for spruce, pine and deciduous trees as a result of the emphasis on regeneration in the forests policy from 1900. The difference between production and growth is the direct cause of forests now accounting for around one third of total greenhouse gas emissions in Norway and for trees with large dimensions, ancient forests and standing and lying dead wood now having increased from low levels.

From a longer time perspective, the development of many forest parameters since 1900 must be viewed in light of having been at a minimum level back then, following extensive forestry activities and poor regeneration for several centuries up to 1900. This may indicate that the current diversity of species has experienced a prolonged period of more challenging living conditions than what we see today, with fewer elements of old and dying trees and dead wood, as these parameters are now increasing from low levels. Such a prolonged period of challenging living conditions must be assumed to have reduced the population for many forest species.

We estimate that around 60 per cent of the known species in mainland Norway are associated with forests. Nearly half of endangered species are associated with forests and, of these, 1132 species are considered to have been negatively impacted by previous or current forestry. This is the background to the extensive environmental registration that provides an overview of biotopes for red-listed species managed as key biotopes, where felling is generally not carried out.

Reindeer husbandry

The Storting has adopted a target for sustainable Reindeer husbandry. The main target comprises three sub-targets: ecological, economic and cultural sustainability. Reindeer husbandry is an important indigenous industry and Sami culture bearer. Reindeer husbandry takes place in an Arctic and sub-Arctic ecosystem based on the ability of reindeer to adapt to the natural environment. Reindeer are physiologically and behaviourally adapted to the environment through rapid growth over a short and intense summer season and reduced activity levels and energy loss in winter. Stakeholders utilise adaptations of reindeer through seasonal relocation of the reindeer herds between different pastures. The natural migration of reindeer and the nomadic herding system form the basis for optimal production in these areas and for Sami reindeer husbandry culture.

Reindeer husbandry is based on reindeer being in outfield pasture all year round, utilising marginal resources. As both the natural conditions and the needs of reindeer vary throughout the year, it is necessary to relocate reindeer between different pastures in various parts of the year. Reindeer husbandry systems vary from district to district and region to region with regard to both pasture use and migration patterns. The biggest difference is found in the farming systems that utilise continental winter pasture with little and dry snow and the farming system that utilises western winter pasture with pronounced coastal climates.

5.5.2 Fisheries and aquaculture sector

Fisheries, harvesting and aquaculture contribute to value creation and food production in Norway. Norway is one of the largest seafood producers in the world and most of the seafood produced in Norway is exported. Fisheries, harvesting and aquaculture all depend on natural conditions and well-functioning ecosystems.

Aquaculture encompasses several different species and operational methods at sea, on land and in lakes and water systems that are associated with different types of impact on e.g. biodiversity, the environment and landscapes. Spatial planning, permits and direct regulation of requirements for the establishment, operation and implementation of aquaculture activities in several regulations constitute key instruments in current aquaculture management. One main objective in the management of aquaculture activities is to ensure the greatest possible value creation within a sustainable framework. Several measures and instruments are relevant in achieving this objective and this has, among other things, been highlighted in the Aquaculture Committee’s report NOU 2023: 23 Integrated management of aquaculture for sustainable value creation. The Government will further address this in the upcoming white paper on aquaculture.

Fisheries primarily affect ecosystems through a proportion of commercial fish stocks being harvested each year. As catches in fisheries rely heavily on functioning ecosystems, sustainable management has been key to Norwegian fisheries management for a long time.

Long-term catch quantities in fisheries are curbed by the production capacity of the fish stocks in question. A fundamental part of Norwegian fisheries management therefore consists of establishing and enforcing quotas for fish stocks to ensure long-term production capacity. This process takes place annually based on scientific advice regarding appropriate levels of fishing. In order for management to be sustainable, the remaining part of the stock must be able to compensate for the quota that is harvested. As the carrying capacity in the marine environment is not constant, stocks must be carefully and frequently monitored in order to record the great variations in recruitment that most fish stocks experience.

Over time, there has been a trend from single stock management to a more ecosystem-based fisheries management, based on precautionary reference points, harvesting patterns and more. This system is continuously evolving.

The large commercial stocks in Norwegian waters are generally in good condition. Nevertheless, fluctuations occur. For example, Norwegian spring-spawning herring are expected to drop below the precautionary level in 2024 due to the high overall fishing pressure and low recruitment. The smallest stocks include Norwegian coastal cod, eel and common redfish and these are still in poor condition, while other species such as the beaked redfish, lesser sand eel and spiny dogfish have experienced stock growth in recent years. The harvesting of target species also affects the ecosystem through its impact on the food chain. This can affect predation pressure for certain species and change food supply or competitive dynamics for others. Norway has therefore committed to an ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management. As part of this work, the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries and the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research have developed a management process that incorporates the fisheries’ impact on the ecosystem, identifying and prioritising challenges for the purpose of follow-up. For example, economically less important fish stocks that are important for biodiversity have been subject to greater attention in research and management. Following the initiation of this work just over a decade ago, the knowledge base and management of these stocks have substantially improved, and the most recent overall assessment from 2021 shows that the status of the majority of these stocks has improved significantly.

Fisheries is the commercial activity that has the greatest direct physical impact on marine areas, due to the geographical extent of bottom fisheries, primarily trawling. On the one hand, this impact is an accepted consequence of effective food production from the sea. Benthic communities such as corals, sponge forests and species that live wholly or partially burrowed in the seabed can be damaged by trawling and other gear touching the seabed. To avoid such damage, a number of areas are subject to special protective measures to safeguard vulnerable species and vulnerable marine ecosystems. Examples of measures include the ban on gear that touches the seabed (bottom fisheries), the ban on bottom fishing at depths exceeding 800 metres, and the protection of coral reefs, sponges and sea pen deposits against harvesting activities. Sustained focus and efforts that consider ecological sustainability in partnership between industry, research and management, will be key to the continued positive development of ecosystem-based fisheries management in Norway.

5.5.3 Industrial sector

There are rich natural resources in Norway. The exploitation of natural resources has been crucial in Western Norway, and this will continue to be the case in the coming years. We will now transform large parts of Norwegian business and industry in a direction that will ensure profitable jobs for the future, reduce emissions, create the green transition and reduce vulnerability.

The Green Industrial Initiative is based on the Government’s governance platform, the Hurdal Platform, which emphasises the link between energy, climate and industrial and business policy. The green industry promise is based on the management of rich natural resources, industrial expertise and regional advantages. In the Roadmap for the Green Industrial Initiative, the Government has clearly set out that Norwegian industry will have access to adequate land and effective infrastructure. At the same time, such projects must be as gentle as possible on their surroundings and safeguard nature to the greatest extent possible. A prerequisite to establish and attract industrial activities in global competition is that there is suitable commercial land available that can be relatively quickly adapted for production. There is plenty to indicate that it is advantageous to establish new industrial production near established commercial land and infrastructure such as near existing industrial parks. This also contributes to taking better care of biodiversity, while industrial establishments can also take place more quickly and enterprises can reduce the need for major new infrastructure investments. At the same time, it is not always possible to realise large new industrial establishments without having to use new land, but this must be done as gently as possible.

In the National Expectations for Regional and Local Planning 2023–2027, the Government has set out an expectation to facilitate the green transition, sustainable value creation and profitable jobs throughout the country. The Government has also established an expectation to facilitate adequate commercial land with minimal negative impact on the climate, environment and society. Commercial land is planned from a regional perspective and energy use, access to power, reuse and more efficient utilisation of existing commercial land and infrastructure are part of the planning assessments.

5.5.4 Mineral sector