7 SDGs in Norwegian Municipalities and Regions

Photo: Jarand K. Løkeland on Unsplash

The following chapter is written by The Norwegian Associations of Local and Regional Authorities.

7.1 Key changes/lessons learned

- Achieving the SDGs largely depends on local and regional authorities’ efforts.

- Political commitment is vital. The political focus impacts on the direction and speed of the SDG localisation.

- Most municipalities and regional authorities have initiated the work. There is, however, a large variation in maturity when it comes to working with the SDGs in the Norwegian municipal sector.

- Recently merged, large, central and network-oriented municipalities have come further, but being ‘big and strong’ is not a prerequisite for success.

- Networks, knowledge-sharing and collaboration across levels of government play a huge role, and the synergies between local and regional level are being exploited to a large degree.

- Only the most mature have operationalised and integrated the SDGs into strategic plans and management processes. These are frontrunners setting an example to the remaining municipalities.

- Although no good benchmarking is available, municipalities and regional authorities contribute substantially to SDG achievement through their regular service delivery, welfare production, planning and development work.

- Further statistical evidence is necessary to reveal how the SDGs have been infused into this work.

7.2 The municipal sector’s significance for the SDGs

The 2030 Agenda commits national governments. Achieving the SDGs, however, depends heavily on the efforts and progress made at the local and regional level. The SDGs cover all aspects of the local government sector’s work, and the international community widely recognises that at least 105 of the 169 targets underlying the 17 SDGs will not be achieved without local and regional authorities. Local and regional authorities are close to citizens, business and civil society.

Effective multi-level governance requires mutual trust. Achieving the SDGs is a shared responsibility; local and regional authorities need to exercise their own powers, to have administrative structures and financial resources, in line with the European Charter of Local Self-Government. The Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS) coordinates consultation between the government and local and regional authorities. Formal, structured and regular consultations three times a year for more than two decades has fostered multi-level governance dialogue in Norway and common intra-government understanding. It has also reduced the need for national regulations or earmarking in budgets, ensured stable funding of local and regional authorities, enhanced local decision-making thereby securing efficient use of resources, and enabled local democracy.

The main localising activities in Norway are initiated by local and regional authorities. Localising has gained momentum and the pace of implementation is considerable. Local and regional authorities collaborate extensively, such as in the Network of Excellence on SDG City Transition consisting of municipalities and regions, which focuses on local SDG initiatives across the country. The network was initiated by several local and regional authorities and organisations, together with KS and the UN Charter Centre of Excellence in Trondheim. To strengthen the efforts of the Norwegian Network of Excellence on SDG City Transition, KS is also working together with the Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise (NHO) and the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO) to develop a national sustainability pledge to strengthen the progress on fulfilling the 2030 Agenda.

7.3 Local and Regional governments’ efforts to localise the SDGs

Over the past couple of years, local and regional governments in Norway have taken significant steps in their efforts to work with, and towards, the SDGs. In fact, in a recent survey conducted in relation to the Voluntary Subnational Review (VSR), 95 per cent of the municipalities and all the regional authorities that responded report that they have started working with the SDGs. However, when asked to evaluate how far they have come, municipal responses are more modest and there are apparent variations as to who has made significant progress in working with the SDGs in a local and regional context. The following paragraphs will elaborate on these variations and outline other key, overarching findings relevant for describing the status and progress on working with the SDGs in the local and regional government sector.

There are large variations between municipalities in terms of commitment, progress and implementation although parts of that variation can be explained. There are large variations in terms of commitment to and implementation of the SDGs across the municipalities. Larger municipalities have a tendency to have worked longer with the SDGs, and these municipalities also seem to be more committed and have come further in implementing the goals. They have also typically come further in leveraging measures to cooperate with both internal and external stakeholders. A similar but less apparent correlation is found for centrality, and in addition, there seems to be higher political priority in more central municipalities. However, there is no clear correlation between budgetary constraints and implementation of the SDGs in the municipal context. This indicates that although financial resources and capacity can be an enabler, large financial and budgetary constraints do not seem to have influenced the speed and progress of the municipalities’ implementation of the goals. Engagement in networks and regional activity, on the other hand, seem to play a key role, particularly when it comes to commitment, cooperation with stakeholders and implementation in management processes.

Although the aforementioned dimensions explain some of the variation in the municipality responses, variation within these dimensions and other unexplained variation mean that there are individual differences between municipalities. As such, although being ‘big’ and ‘central’ may increase the likelihood of being ahead in working with the SDGs, there are several cases where municipalities with fewer available resources thrive in this space.

CASE: The Norwegian Network of Excellence on SDG City Transition

Several municipalities, regional authorities and organisations, together with KS, formed a network to join forces in localising the SDGs, demonstrate local adaption and accelerate impact by linking local action to regional, national and international partners for knowledge-sharing and funding. The network is an ongoing prototyping of a multi-level and multi-stakeholder approach to sustainable development and is collaborating closely with the UN initiative United for Smart Sustainable Cities (U4SSC). The network, which is expanding rapidly, builds on the Stavanger Declaration and sets out to:

- spread knowledge about the status to the community;

- develop plans for community development that illustrate how to achieve the SDGs;

- mobilise and support citizens, businesses, organisations and academia that contribute to sustainable development;

- measure and evaluate the effort, through the U4SSC Implementation programme and other methods.

The regional authorities mobilise and engage the municipalities in their work with the SDGs. Lack of guidelines and support from national authorities are key barriers at the regional level. While the municipalities look to the regional authority, KS and other municipalities for collaboration and support, the regional authorities seem to rely more heavily on support from the national level. There is considerable collaboration and network activity across local and regional government level. The majority of the municipalities have participated in regional networks or programmes, and the regional authority is their most used collaboration partner. Likewise, all the regional authorities have used establishment of or participation in networks as a means of involving the municipalities. As such, the synergies between the local and regional level seems to be leveraged to a large degree. The regional authorities, however, report lack of support and clear guidelines from the national level as a key barrier.

CASE: The Sustainability County Møre og Romsdal

The Sustainability County Møre og Romsdal is a regional authority initiative to collectively boost the work on sustainability in the region. With this initiative, the county wants to position themselves as a clear contributor in developing a sustainable society for the future. The goal is to direct the regions’ efforts towards achieving the SDGs in a methodical and coordinated manner. To achieve this, on the regional authority’s initiative, all the municipalities in the region have collected data and measured performance and progress according to U4SSC’s KPIs. This is to ensure that all the municipalities and the regional authority have a common knowledge base for further work. Cooperation with businesses, associations, the voluntary sector, the culture sector and the research community in the county is also central to the efforts in the sustainability county.

Municipalities and regional authorities have incorporated the SDGs into their strategy and vision. Asker, Kristiansund and Arendal, among others, use the SDGs as a basis for municipal plans and incorporate the goals into management systems. Large or recently merged municipalities have had a head start in implementing the SDGs in the municipal planning system. Municipal master plans best provide evidence for SDG incorporation. There is currently a large variation in the implementation of the goals in the municipal planning system. This is expected to change when all municipalities and regional authorities have updated their plans before the end of the current council period, in compliance with the national planning expectations. Some municipalities have already made good progress in fully integrating the SDGs in budgeting and procurement processes. Many municipalities and regional authorities point to operationalisation as both a key success factor and a barrier. Several municipalities report that it is challenging to work systematically, strategically, knowledge-based and plan-driven with the SDGs.

The most mature municipalities have measures and report on progress towards the goals. Half of the regional authorities and a quarter of the municipalities have measured progress on the SDGs. The majority of those that have not yet conducted monitoring are planning for it, which indicates a positive future development in this field. For both the regional authorities and the municipalities, participation in the Norwegian Network of Excellence on SDG City Transition seems to trigger this process. The Network collaborates closely with U4SSC, and several of the participants have used the U4SSC’s set of KPIs to monitor progress and measure how smart and sustainable they are. Additionally, Viken regional authority has used the OECD’s set of indicators to measure progress and has developed a Knowledge Base using the SDGs as the overall framework. Statistics Norway has, on commission from KS, developed a classification of SDG-related indicators that will facilitate a common approach to monitoring. As such, there are frontrunners leading the way when it comes to measuring and reporting progress on the SDGs.

CASE: Taxonomy for classification of SDG-related indicators

Stimulated by the need for useful tools to connect the global goals to local and regional activities and projects, KS partnered with Statistics Norway to develop a taxonomy for SDG indicators. Applying a common standard taxonomy to all SDG indicators helps to clarify their use and usability. The taxonomy proposes three dimensions for sorting SDG indicators; Goal, Perspective and Quality, and together they cover the central properties of any SDG indicator, with respect to its target, use and usability.

There are large variations when it comes to access to appropriate tools and methods for implementing the SDGs, both for the municipalities and the regional authorities. The small municipalities seem to be at a disadvantage. There is scope for devising new methods and tools and making these accessible to all. Participation in networks, and particularly the Norwegian Network of Excellence on SDG City Transition has a positive impact on access to relevant tools and methods. This indicates the importance of networking and knowledge-sharing.

Recently merged municipalities have made more progress in implementing the SDGs across strategy, plans and operationalisation. Merger processes seem to be a trigger for change and a stronger focus on the SDGs. This process serves as a clean slate for developing strategies and management systems, in which the SDGs seem to have stood out as a relevant framework for structuring the work, while providing a common direction and purpose for the new municipality.

CASE: The SDGs and Norwegian territorial reform

In the merger between Hurum, Røyken and Asker, the new Asker municipality decided to set up the new municipality based on the SDGs, and used the goals as a framework for the municipal plan and underlying plans. They wanted to demonstrate that the global goals also have local relevance, and thereby engage citizens, businesses and voluntary organisations and encourage teamwork in achieving the goals. Asker’s innovative merger process has inspired others, including Nordre Follo municipality and Viken county, who like Asker, built their new authority with the SDGs as a foundation.

Political commitment is vital. The municipalities with a political focus on the SDGs have generally come further when it comes to integrating the SDGs in the municipality plans. This indicates that the political level has the potential to impact the direction and speed of the SDG localisation. Lack of political prioritisation is also considered an important barrier by several of the municipalities and regional authorities. The municipalities Aremark and Bodø, as well as Viken regional authority, and others, have established a systematic approach for involving the political level in the operationalisation of the SDGs using templates to manage and process background documents. Consequently, the SDGs become an integral part of political decisions.

There is consensus that the SDGs have potential to create new ways of working, cross-sectoral partnerships and innovation. Most regional authorities and one third of the municipalities use the SDGs to create new ways of working and new partnerships. Regional authorities use the SDGs to create new partnerships internally in the administration, with external stakeholders and across levels of government. Using the SDGs as a trigger for new, value-driven initiatives is key to leveraging the SDG framework’s potential.

COVID-19 does not seem to have had a significant impact on the regional management level’s SDG efforts. The pandemic has tied up resources, which has reduced municipalities and regional authorities’ capacity for working with the SDGs. There is potential in working holistically and cross-sectorally, and a value in creating a sense of cooperation and mutual recognition of facing a difficult situation together. This can and should be translated into a broader SDG perspective following the pandemic.

7.4 Progress on SDGs and targets

Municipalities and regional authorities make a substantial contribution to the achievement of the SDGs through their regular service delivery, welfare production, planning and development work. It should be noted that even though the municipal sector is performing well on many of the SDGs and targets compared to national and international standards, many are striving to improve performance even more.

SDG indicators are still lacking for regional and local authorities. However, progress can be monitored using existing data sources. A holistic approach, demonstrating inter-connectivity between SDGs and targets, becomes clear when structured around the municipal sector’s own six priority policy areas, as committed to in KS’s National Congress in 2020.

More than 30 municipalities have conducted KPI monitoring according to the U4SSC. Norway was the first country to apply the U4SSC KPIs for smart and sustainable cities to an entire network of cities.

Figure 7.1 U4SSC Norway Disc

Source: U4SSC

7.4.1 Adolescents and quality of life (SDGs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 16 and 17)

The municipal sector facilitates most of the health services, well-being, attractive centres, good meeting places, inclusion, higher upper secondary completion rates and social equality. The municipal sector’s targeted work seeks to provide good conditions for adolescents, the local environment, public goods, participation in work, activities and social life and opportunities for quality of life and life management, regardless of age and living conditions.

The municipal sector is making good progress and performing well in terms of U4SSC, especially within education and health. These findings are substantiated by a biannual citizens’ satisfaction survey, which shows that three-quarters of Norwegians are satisfied with their municipalities.

Figure 7.2 Perception of municipalities

Source: The Norwegian Agency for Public and Financial Management (DFØ)

Youth are less satisfied with their local communities than the rest of the population, and feel lonelier. The feeling of loneliness among young people has increased during the pandemic lockdown.

Figure 7.3 Loneliness among upper secondary school pupils

Source: Norwegian Institute of Public Health

7.4.2 Climate and environmentally friendly development (SDGs 6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 17)

The municipal sector is taking active leadership in the transition to a climate-friendly and environmentally friendly society. Municipalities and regional authorities have set ambitious climate targets and aim to be forward-looking in the green transition. Many of the targets are far more ambitious than the national goals. The strategies to achieve these goals include transforming into a low-emission society, facilitating land use and infrastructure that reduce emissions and energy consumption, and implementing necessary measures to limit the effects of a changing climate.

Regional authorities are phasing in electric transport. More than 70 emission-free battery-driven ferries will soon be in operation, which accounts for around one third of the total fleet. The number of electric buses more than doubled in 2020, to a total of 410. Around 120 new electric buses have been contracted for 2021.

Figure 7.4 Passengers on public transport

Source: Statistics Norway

The number of journeys using public transport increased by half a per cent in 2019 to 695 million. Almost 90 per cent of passengers use regional authority transport. Nevertheless, according to U4SSC, the Norwegian municipal sector may perform better in the transport sector. The development has largely been driven by the city centres, and there has been poor utilisation of more mobile and innovative modes of transport, as well as systematic use of monitoring data. For obvious public health reasons, use of public transport has decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is expected that some of the decrease will be permanent due to the increased use of home offices and greater awareness of congestion.

Sustainable land management is an important part of the work to preserve biodiversity, secure food production and reduce climate emissions.

Figure 7.5 Reallocation of arable land

Source: Statistics Norway

Land use changes are the main source of loss of biological diversity. Areas used for cultivation and areas that can be used for cultivation are repurposed for transport infrastructure, housing, commercial buildings and energy production. This trend has been declining in recent years. Production of electric power has increased in recent years to a total of 154.2 Twh. At the end of 2020, 297 square kilometres was required for wind power alone, an area that is rapidly growing. The species database currently classifies 2,000 species and 74 habitats as endangered.

Figure 7.6 Repurposed land

Source: Statistics Norway

7.4.3 Adaptable business community (SDGs 8, 9, 11, 12 and 17)

As community developers, the municipalities and regional authorities set out to facilitate sustainable development, innovation and value creation in the private and public sector. New technology and collaboration between business, academia and the public provide robust infrastructure and commercial opportunities, ensuring that everyone has somewhere decent to live, good welfare services and attractive communities. For businesses, good conditions for green restructuring as well as digital and physical infrastructure are important for maintaining and expanding commercial activity and creating jobs. The development and use of new technologies can help solve major environmental and climate challenges. Municipalities and regional authorities play an important role for the private sector through procurement and investment projects. The public sector must lead the way in green restructuring, inclusive workplaces and professionalism.

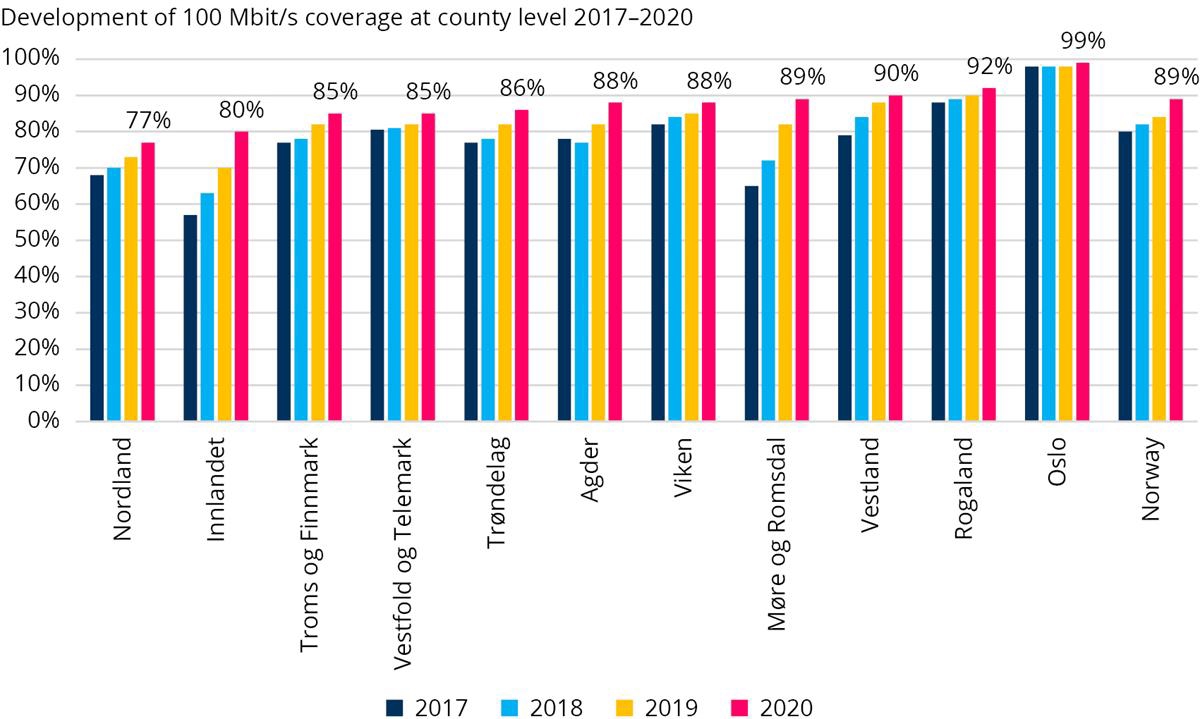

A prerequisite for an adaptable business sector and a digital public sector is that businesses, public agencies and residents in the municipality have access to high-speed broadband. The national goal of 90 per cent of households with at least 100 Mbit/s internet access by 2020 has nearly been achieved. In 2020, the responsibility for distributing development grants for internet access was transferred to the regional authorities. The coverage has increased sharply in areas with the lowest coverage. Despite good infrastructure, high competent businesses and residents who are quick to adopt the technology, U4SSC shows that the technology is not sufficiently used to innovate and further develop businesses and services.

Figure 7.7 Internet connection

Source: Norwegian Communications Authority (Nkom)

Procurements are another important means for the municipal sector to facilitate an adaptive business sector. Seventy-five per cent of the regional authorities and 59 per cent of the municipalities have a procurement strategy. This is higher than authorities at the national level, where 48 per cent have a procurement strategy. The municipality sector places an emphasis on climate and environment, ethics, wages and working conditions and social responsibility. Innovative public procurements represent a small percentage of the total procurements.

Figure 7.8 Public procurement

Source: The Norwegian Agency for Public and Financial Management (DFØ)

7.4.4 Attractive places and cities (SDGs 3, 6, 9, 10, 11 and 17)

Developing attractive places is important for the climate, living conditions and business. The municipal sector develops vibrant communities with good meeting arenas for people. Through regional plans, the regional authorities work on coordinating housing, land and transport planning. The emphasis on attractive places and cities is partly a reaction to the loss of business and activity in the local city areas over time , and partly due to a desire for positive development and better quality.

Many municipalities are working to increase attractiveness for people and businesses. Important factors are clean air and clean water, absence of noise and good access with short distances to workplaces, public transport and service, leisure and cultural facilities. According to U4SSC, the municipalities score highly on important factors such as noise, dust and water. These findings are reflected in a citizens’ satisfaction survey, which indicates that the population has a positive perception of waste management, safety, the environment and proximity to primary schools. The population’s view of the possibility of engaging in activities has weakened somewhat in recent years.

Figure 7.9 Perception of public services

Source: The Norwegian Agency for Public and Financial Management (DFØ)

Social dialogue is an integral part of the Norwegian welfare model, and has resulted in permanent employment and decent pay, good working conditions and high productivity and flexibility. There is a close and satisfactory cooperation between the municipal sector and local trade union representatives.

Figure 7.10 Social dialogue

Source: KS

7.4.5 Diversity and inclusion (SDGs 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 16 and 17)

Diversity and inclusion are linked to public health, attractive locations, business, upbringing and education. Diversity and inclusion require respect for other people, regardless of sexual orientation, beliefs, opinions and cultural expressions. Inclusion is also largely about the inclusion of newcomers and asylum seekers and about inclusion in local communities and working life. Society is built from the bottom up.

Norway is a diverse society. Results from U4SSC, as well as other statistics, raise concerns about trends in diversity and inclusion, particularly among children and youth. The proportion of children growing up in families with a persistent low income has increased. Overcrowding is increasing for those with the lowest incomes. Cramped conditions make it difficult to bring friends home and to have space and peace for schoolwork.

Figure 7.11 Household poverty

Source: Statistics Norway

Exclusion of youth is still a challenge in the Norwegian society. Although drop-out rates have fallen in recent years, numbers are too high. This is especially true for vocational subjects. Drop-out rates amongst immigrant, especially refugee, children are higher than amongst children in general. The reasons for dropping out are many and complex, but it is partly related to the pupil’s results from primary school, background and motivation for schoolwork.

The proportion of people of working age who receive disability benefits is high, and the proportion of youth in this group is increasing. An estimated 120,000 young people between the ages of 20 and 30 are not in education, employment or training. Mental disorders are an important cause of disability among young people and those who drop out of education and working life, generating high life-span costs.

7.4.6 Citizens’ participation (SDGs 5, 10, 16 and 17)

The municipal sector is committed to promoting participation in a transparent, vibrant and engaging local democracy that interacts with the private and the voluntary sector. The municipal sector is committed to providing meeting places and venues, adopting new methods for dialogue, working with clear language and transmitting active information and communication. Involving citizens in the political processes increases the opportunities for democratic participation and influence.

Election turnout increased significantly in 2019, with the largest increase among youth. The citizens prefer to have elected representatives in their own municipal council as a channel for promoting their interests. However, they are not completely satisfied with how politicians involve citizens and listen to their views.

Trust in both national and local institutions and actors has decreased somewhat from 2007 to 2019, and more so for national than local institutions. Numbers from 2020 suggest that public trust is growing again.

Figure 7.12 Public trust

Source: Institute for Social Research

Hatred and threats prevent participation. Forty per cent of local politicians have been exposed to hate speech or specific threats. Younger politicians are more exposed. The large scale of hate speech and concrete threats against local elected representatives is a danger to freedom of expression and democracy.

7.5 Local governments’ message to the Government

Based on assessments of local and regional authorities’ efforts and progress on the SDGs, KS recommends the following;

- Political commitment and leadership at all levels of government is required to achieve the SDGs.

- Upholding multi-level governance, policy coherence and multi-stakeholder partnerships is essential for SDG implementation. Identifying critical interdependencies between action areas to pursue a coherent approach to SDG implementation and limit negative spillovers.

- Local and regional authorities must be fully consulted at each step of the national decision-making process. Periodic progress assessments (VNR and VSR) must expedite and determine the direction of SDG fulfilment.

- Regional authorities need adequate support mechanisms and tools to mobilise and engage the municipalities, such as appropriate SDG indicators for regional and local authorities.

- Continued sharing and learning from peers, as well as to emphasise experimentation and innovation with a view to finding better solutions to common challenges.